Abstract

Breast metastases in cases of leukemia are rare. We aimed to report the conventional-advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of unilateral breast involvement of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and review the literature. A 32-year-old woman was first diagnosed with ALL in treated in 2004. She did not continue the follow-up after 2008. She was presented with a giant, progressive right breast palpable mass in 2010. Mass, contralateral breast tissue were evaluated with MRI, diffusion weighted imaging and MR spectroscopy. With MRI findings, lesion was evaluated as malignant, tru-cut biopsy revealed recurrence of ALL. Lymphoma, malignant melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma are most common tumors metastase to breast. Breast metastases of leukemia are rare and occur primarily in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Secondary ALL breast involvement is uncommon. In a patient with malignancy, any enlarging breast mass, even with benign radiologic appearance, should be investigated carefully and metastasis should not be forgotten.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Breast, Magnetic resonance imaging, Neoplasm metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Metastasis of extramammarian malignancies to the breast are very unusual. Lymphoma, malign melanoma and rhabdomyosarcoma are the most common tumors that metastasize to the breast tissue. Breast metastases in cases of leukemia are very rare and occur primarily in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) involment of the breast is uncommon [1,2]. We experienced a case of ALL with giant breast involvement. We report the conventional and advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of unilateral breast involvement of ALL and review the literature.

CASE REPORT

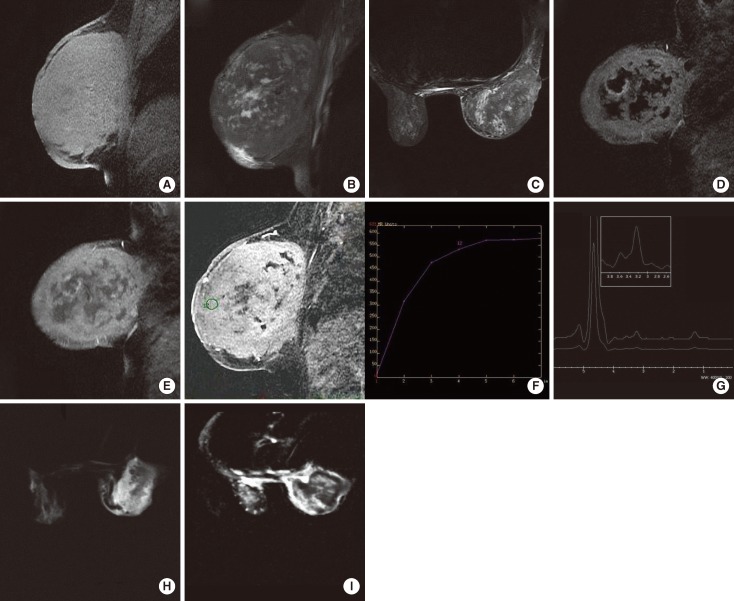

A 32-year-old woman with ALL under remission was admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine in our institution. This patient was first diagnosed with ALL in June 2004 and was treated between June and December 2004. She was under follow-up with remission until 2008. The patient who had no complaints stop referring to the hospital afterwards. Unfortunately she presented with a breast lump in September 2010. The giant mass, involving the whole right breast at the time of presentation grew progressively in a period of 3 months. The lump was immobile during physical examination. The breast was red and hot. Skin thickening and prominent superficial venous structures accompanied. There was no dimpling, skin erosion or nipple discharge. Axillary lymph nodes were also palpable. Additionally she had weakness, fatigue. The patient was referred to the radiology clinic for the evaluation of the breast. Ultrasonography (US) demonstrated a giant breast mass with necrotic center. US showed a giant breast mass with a necrotic center. The mass and contralateral breast tissue was further evaluated with MRI, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and MR spectroscopy. MRI was done with a 1.5 Tesla MR device (Signa HDx; General Electric, Milwaukee, USA). The routine sequences were axial short TI inversion recovery (STIR), sagittal fast spin echo (FSE), fat saturated T2W, sagittal 3D VIBRANT (postcontrast fat saturated T1W). We added DWI with b=0 and b=600 values and BREASE (single Voxel MR Spectroscopy) sequence. The giant right breast mass was hyperintense-isointense on precontrast fat saturated T1W images (Figure 1A) and heterogeneously hypointense-hyperintense on STIR and fat saturated T2W images (Figure 1B and 1C). In the VIBRANT sequence, there was a prominent enhancement of the solid components (Figure 1D and 1E). Time-signal intensity curves obtained by post-processing were classified as type 2 (Figure 1F). The lesion was hyperintense on DWI (Figure 1G), and hypointense in apparent coefficient diffusion (ADC) maps (Figure 1H). The ADC value was extremely low (3.12×10-6 mm2/sec) representing prominent restricted diffusion. A prominent choline peak compatible with malignancy was detected at 3.2 ppm in the BREASE sequence (Figure 1I). There were also multiple malignant lymph nodes. There was no sign of chest wall invasion and the other breast was normal. With these findings the lesion was evaluated as a malignant lesion and core needle was applied. Core needle biopsy revealed recurrence of ALL (Figure 2). The cellularity of the mass was 95% and 80% of the cells were blastic. CD34 (+), Tdt (+), CD20 (-), CD3 (-), CD79 (-), MPO (-) were found in immunhistochemical analysis. A new chemotherapy regimen was started, but unfortunately the treatment was not successful and the patient died.

Figure 1.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia presenting as a giant breast mass in a 32-year-old woman. (A) Both the solid and necrotic components of the giant lesion in the right breast are hyperintense-isointense on precontrast fat saturated T1W images. (B) On fast spin echo, fat saturated T2W image of the solid and the necrotic parts of the lesion are hypointense-hyperintense. (C) On short TI inversion recovery image the signal characteristics are similar to the fat saturated T2W image. (D) Subtracted and (E) post contrast fat saturated T1W images, there is prominent enhancement. (F) Type 2 (plateau type, doubtful type) curve pattern is obtained from the enhanced involved breast tissue. (G) On diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), nearly the whole breast is hyperintense. (H) In the apparent coefficient diffusion (ADC) map, hyperintense parts on DWI image are hypointense indicating restricted diffusion. The necrotic parts are hyperintense. ADC value: 3.12×10-6 mm2/sec. (I) There is a prominent choline peak at 3.2 ppm in the BREASE sequence.

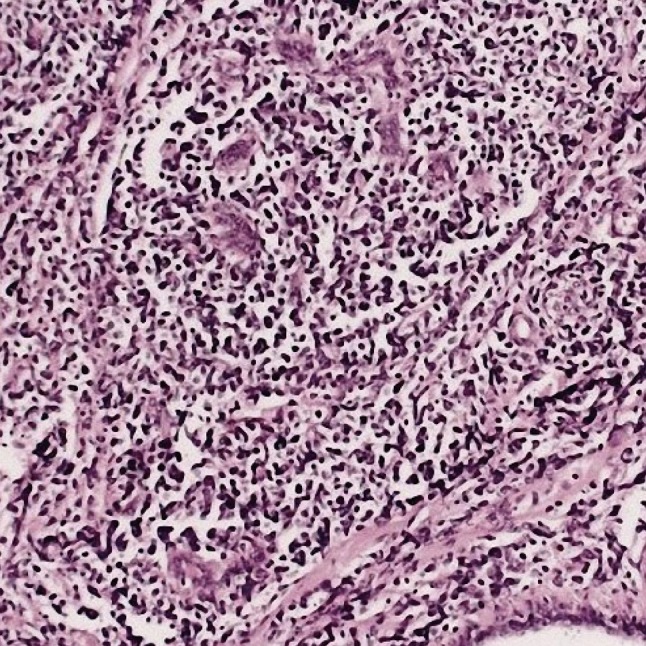

Figure 2.

There is leukemic blasts infiltrating the breast tissue (H&E stain, ×100).

DISCUSSION

Metastases to the breast from extramammary malignant neoplasms are unusual and were described first in 1903. Breast metastases may be the initial manifestation of malignant disease. Nipple retraction is usually absent and axillary nodal involvement is frequent. Metastatic cancer to the breast is often discovered as a superficial solitary mass (85%), located in the upper outer quadrant (66%) [3]. Metastases are frequently multiple and bilateral, but they are more commonly large, solitary tumors [4]. They clinically manifest as well marginated, mobile, rapidly enlarging masses [5].

Metastatic breast leukemia is very rare and occurs primarily in patients with acute myeloid leukemia [6]. MRI features include T2 hyperintensity and rapid ring-enhancement of the lesions [7]. The explanation of this ring-enhancement is reported due to the central necrosis and peripheral angiogenesis in the literature [8].

Malignant tumors, show attenuated diffusion on DWI, and the ADC values are low secondary to high cellular density. Malignant lesions are hyperintense on DWI images and hypointense on ADC maps. Necrotic areas are hyperintense in both DWI and ADC maps [9]. During pathologic situations, the chemical content of tissues and organs change. Choline takes part in cellular membrane turn-over and is a marker of cellular proliferation. In malignancy, the choline concentration increases as a result of both intracellular phosphocholine and high cellular density of the lesion. Moreover, it was reported that high choline content was compatible with the increase of angiogenetic activity [10].

In our case both conventional and advanced MRI findings were compatible with the literature. The extremely rare involvement of the breast in cases of leukemia can be the only complaint at initial presentation or seen as relapse. Moreover, radiotherapy performed for breast malignancies can also cause acute leukemia in breast tissue [2].

In a patient with a known malignancy, any enlarging breast mass, even one with a reassuring benign sonographic appearance must be investigated promptly [11], initially with fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy [4]. Breast metastases are usually associated with disease originating elsewhere, and the prognosis is generally poor [12].

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Likaki-Karatza E, Mpadra FA, Karamouzis MV, Ravazoula P, Koukouras D, Margariti S, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapse in the breast diagnosed with gray-scale and color Doppler sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:552–556. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoury NJ, Hanna Al-Kass FM, Jaafar HN, Taher AT, Shamseddine AI. Bilateral breast involvement in acute myelogenous leukemia. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1031. doi: 10.1007/s003300051059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrea ES, Johnston C, Haney PJ. Metastases to the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:685–690. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hays DM, Donaldson SS, Shimada H, Crist WM, Newton WA, Jr, Andrassy RJ, et al. Primary and metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma in the breast: neoplasms of adolescent females, a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:181–189. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199709)29:3<181::aid-mpo4>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham I. A clinical review of breast involvement in acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2517–2526. doi: 10.1080/10428190600967022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang WT, Muttarak M, Ho LW. Nonmammary malignancies of the breast: ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2000;21:375–394. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(00)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang WT, Metreweli C. Sonography of nonmammary malignancies of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:343–348. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakovljević B, Stevanović O, Bacić G. Metastases to the breast from small-cell lung cancer: MR findings. A case report. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:485–488. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2003.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh DM, Collins DJ. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the body: applications and challenges in oncology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1622–1635. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mountford C, Lean C, Malycha P, Russell P. Proton spectroscopy provides accurate pathology on biopsy and in vivo. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:459–477. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR, 3rd, Grosfeld JL. Diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic breast masses in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:182–186. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers DA, Lobe TE, Rao BN, Fleming ID, Schropp KP, Pratt AS, et al. Breast malignancy in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:48–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]