Abstract

Background

Most studies of heart failure (HF) in Medicare beneficiaries have excluded patients age <65 years. We examined baseline characteristics, quality of care, and outcomes among younger and older Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with HF in the Alabama Heart Failure Project.

Methods

Of the 8049 Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF in 1998–2001 from 106 Alabama hospitals, 991 (12%) were younger (age <65 years). After excluding 171 patients discharge to hospice care, 7867 patients were considered eligible for left ventricular systolic function (LVSF) evaluation and 2211 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction <45% and without contraindications were eligible for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy.

Results

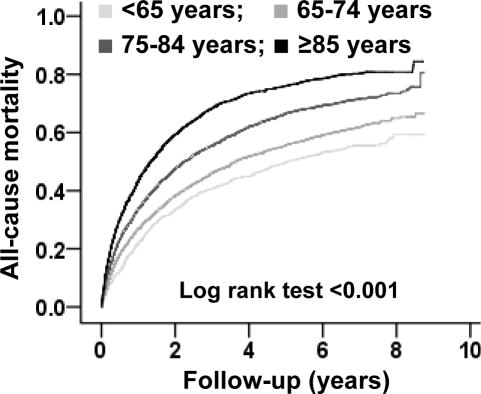

Nearly half of the younger HF patients (45% versus 22% for ≥65 years; p<0.001) were African American. LVSF was evaluated in 72%, 72%, 70% and 60% (overall p<0.001) and discharge prescriptions of ACE inhibitors or ARBs were given to 83%, 77%, 75% and 75% of eligible patients (overall p=0.013) among those <65, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years, respectively. During 9 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality occurred in 54%, 61%, 71% and 80% (overall p<0.001) and hospital readmission due to worsening HF occurred in 65%, 60%, 55% and 48% (overall p<0.001) of those <65, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years, respectively.

Conclusion

Medicare beneficiaries <65 years with HF, nearly half of whom were African American, generally received better quality of care, had lower mortality, but had higher re-hospitalizations due to HF.

Keywords: heart failure, age, Medicare, quality of care, outcomes

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is the leading cause of hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries 65 years and older in the United States [1]. Medicare is a national health insurance program for people ≥65 years in the United States and individuals <65 years of age with certain disabilities including HF may qualify for Medicare benefits. However, because younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF have often been excluded from studies of HF in Medicare beneficiaries, little is known about these patients [2–9]. Therefore, in the current study, we examined baseline characteristics, quality of care, and natural history for younger and older Medicare beneficiaries in the Alabama Heart Failure Project (AHFP) registry.

Methods

Data Source

The AHFP was conducted by the Alabama Quality Assurance Foundation (AQAF), the Quality Improvement Organization for the state of Alabama, to assess and improve the quality of care of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with HF. It began as a part of the National Heart Failure Project implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) [2] and was later complemented with additional state-level projects.

Medical records of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged with a principle discharge diagnosis of HF from 106 Alabama hospitals between July 1, 1998 and October 31, 2001 were identified and abstracted in six different six-month periods (Box 1). The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 428, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91 and 404.93 were used to identify charts with a principle discharge diagnosis of HF. During each period, a systematic random sample of charts was drawn after stratifying by patients’ age, sex, race and hospital. Patients who were transferred to another acute care hospital, had procedure codes indicating dialysis (ICD-9-CM codes: 39.95 or 54.98) or were discharged against medical advice were excluded.

Box 1. Alabama Heart Failure Project datasets by number of charts and discharge dates.

| Datasets | Discharge Dates | Number of Charts Abstracted |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 | July 1, 1998–December 31,1998 | 874 |

| Cohort 2 | May 1, 1999–October 31,1999 | 988 |

| Cohort 3 | November 1, 1999–April 30, 2000 | 1924 |

| Cohort 4 | May 1, 2000–October 31, 2000 | 1988 |

| Cohort 5 | November 1, 2000–April 30, 2001 | 1921 |

| Cohort 6 | May 1, 2001–October 31, 2001 | 1954 |

| All | July 1998–October 2001 | 9649 |

The selected medical records were then transferred from participating hospitals to the Central Clinical Data Abstraction Centers (CDAC), located in York, Pennsylvania for data abstraction. Trained CDAC technicians abstracted data from the 9649 charts directly into a computer database using a data collection tool programmed by MedQuest Software. CDAC ensured reliability of the abstraction process through internal and external re-abstractions of 40 charts monthly. Reliability findings demonstrated agreement values >80% and Kappa values >0.60.

Using a set of unique identifiers including dates of birth, social security numbers, and Medicare claim numbers, AQAF identified a cohort of 8555 unique patients from the database of 9649 hospitalizations. The final database of 8555 patients was deidentified by the Iowa Foundation for Medical Care, the Quality Improvement Organization for the state of Iowa, designated by the CMS for data deidentification. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Baseline Data Collection

Data on baseline characteristics and hospital course were collected by chart abstraction and included demographics, past medical history including use of medications, hospital course, discharge disposition and medications, and physician specialty. Data were also collected on the receipt of cardiology care, via consultation or as primary care.

Quality Indicators

Trained CDAC technicians abstracted the selected medical records for data on the four core evidence-based quality indicators for HF including evaluation of left ventricular systolic function (LVSF), discharge prescription of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for HF patients with reduced left ventricular ejection function (LVEF), receipt of a complete discharge instruction, and counseling for smoking cessation.

Data on LVSF evaluation was evaluated by both review of echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography, or contrast ventriculography performed during index or prior hospitalizations. Because AHFP was a quality improvement project, data on future plans for LVSF evaluation were also collected. Data on LVEF were collected as a continuous variable. However, when data on LVEF were not available, descriptive data on LVSF were used, and normal, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, and severely impaired LVSF were categorized into LVEF 55%, 45%, 35%, and 25% respectively. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) was defined as LVEF <45%. LVSD of unknown severity was considered to have LVEF 35%.

In addition to the discharge prescription of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, data on discharge prescription of beta-blockers and other medications were also collected by chart abstraction. Discharge instructions included instructions on medication, weight monitoring, diet, activity, follow-up and warning symptoms. Data on counseling for smoking cessation were either documented as “given” or “missing”.

Outcomes Data

Data on mortality and hospitalization between July 1, 1998 and April 2, 2007 were obtained from CMS Medicare utilization files, which are based on fee-for-service claims data and do not include Medicare managed care claims. Because the earliest discharge date in the first AHFP project was July 1, 1998, data on outcomes were collected from that date. At the time of the linking to outcomes data, the latest data were available through April 2, 2007. Data on mortality and time of death were obtained from the CMS Denominator File, which contains data on dates of birth and death for each Medicare beneficiary enrolled in Medicare during a calendar year. Data on hospitalization and time to hospitalization from July 1, 1998 through April 2, 2007, were obtained from the CMS Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file, which contains inpatient hospital final action stay records. Each inpatient hospital MedPAR record represents a stay in that hospital and summarizes all services rendered to a beneficiary from the time of admission to a facility through discharge. Additional data on diagnosis, (ICD-9 diagnosis), procedure (ICD-9 procedure code), Diagnosis Related Group (DRG), dates of service, and reimbursement amount were obtained from the Inpatient Standard Analytical Files. Patients who were admitted to out-of-state hospitals or those who did not have Medicare pay for their hospitalizations were not included.

Statistical Analysis

For the current study, we restricted our analysis to 8049 patients who were discharged alive from the hospital. Patients were stratified into four groups based on their age: <65 years, 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and ≥85 years. Patient discharged to hospice care (n=171) were excluded from the denominator of the analysis of LVSF evaluation. The remaining 7867 patients were considered eligible for LVSF evaluation (past, present or future). Of these, 2211 with LVSD and without contraindication (Box 2) were eligible for discharge prescription of ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Overall, 83% (n=6676) were eligible for written discharge instructions and 11% (n=910) were eligible for smoking cessation counseling (Box 2). We also compared the rates of appropriate beta-blocker use by identifying a subset of 2675 eligible patients who were not discharged to hospice care and had an LVEF <45%, a heart rate ≥60 beats per minute, and a systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg.

Box 2. Quality Indicator Eligibility Criteria.

Left ventricular systolic function evaluation

|

Discharge prescription of ACE inhibitors or ARBs

|

Written discharge instructions

|

Counseling for smoking cessation

|

We used the Pearson’s chi-square test and one-way ANOVA to compare baseline characteristics, index hospitalization events, all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalization, HF hospitalization, and the combined end points of HF hospitalization or all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality for all patients discharged alive (n=8049) by four age groups: <65, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years. Similar approach was used for quality of care analyses. However, those ineligible for specific quality indicators were excluded from their specific analyses. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to determine the association of the age groups with all-cause mortality during about 9 years of follow-up. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. SPSS (Rel. 18, 2009. Chicago: SPSS Inc.) for Windows was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Patients (n=8049) had a mean age (±SD) of 76 (±11) years, 58% were women and 25% were African American. A higher proportion of younger HF patients were African American (45% versus 22% for ≥65 years; P<0.001), smokers (30% versus 9%; p<0.001) and had diabetes mellitus (58% versus 41%; p<0.001). However, a lower proportion of younger HF patients had chronic kidney disease (50% versus 66%; p<0.001). Baseline patient and care characteristics of patients by the four age categories are displayed in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively. Among HF patients <65, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years of age who had data on LVEF, mean LVEF was 37%, 39%, 41%, and 44%, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by age

| n (%) or mean (±SD) | <65 years (n=991) | 65–74 years (n=2382) | 75–84 years (n=2978) | ≥85 years (n=1698) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56 (±7) | 70 (±3) | 79 (±3) | 89 (±4) | <0.001 |

| Female | 416 (42%) | 1217 (51%) | 1765 (59%) | 1229 (72%) | <0.001 |

| African American | 446 (45%) | 630 (26%) | 580 (20%) | 338 (20%) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 293 (30%) | 366 (15%) | 222 (8%) | 41 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Admitted from nursing home | 13 (1%) | 73 (3%) | 205 (7%) | 254 (15%) | <0.001 |

| Prior hospitalization (during 1 year) | |||||

| Due to any cause | 544 (55%) | 1187 (50%) | 1498 (50%) | 837 (49%) | 0.028 |

| Due to heart failure | 212 (21%) | 473 (20%) | 538 (18%) | 281 (17%) | 0.005 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Heart failure | 722 (73%) | 1672 (70%) | 2149 (72%) | 1269 (75%) | 0.015 |

| Coronary artery disease | 523 (53%) | 1414 (59%) | 1702 (57%) | 769 (45%) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 258 (26%) | 620 (26%) | 698 (23%) | 319 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Angina pectoris | 124 (13%) | 377 (16%) | 437 (15%) | 239 (14%) | 0.082 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 179 (18%) | 393 (17%) | 405 (14%) | 110 (7%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 249 (25%) | 716 (30%) | 760 (26%) | 216 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 138 (14%) | 545 (23%) | 871 (29%) | 572 (34%) | <0.001 |

| Left bundle branch block | 93 (9%) | 319 (13%) | 449 (15%) | 218 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 737 (74%) | 1703 (72%) | 2103 (71%) | 1075 (63%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 574 (58%) | 1237 (52%) | 1218 (41%) | 470 (28%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 498 (50%) | 1440 (61%) | 2007 (67%) | 1180 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 186 (19%) | 441 (19%) | 673 (23%) | 356 (21%) | 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 415 (42%) | 920 (39%) | 1073 (36%) | 447 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 5 (1%) | 89 (4%) | 348 (12%) | 310 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 9 (1%) | 68 (3%) | 64 (2%) | 27 (2%) | 0.001 |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Pulse, beats per minute (n=8031) | 93 (±22) | 90 (±22) | 89 (±23) | 88 (±22) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 147 (±35) | 150 (±33) | 149 (±32) | 150 (±31) | 0.127 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (n=8028) | 84 (±21) | 80 (±19) | 79 (±19) | 78 (±19) | <0.001 |

| Respiration, per minute (n=8003) | 23 (±6) | 24 (±6) | 24 (±6) | 24 (±7) | 0.006 |

| Temperature (n=8003) | 97.8 (±1.4) | 97.7 (±1.3) | 97.6 (±1.2) | 97.6 (±1.2) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral edema | 734 (74%) | 1691 (71%) | 2049 (69%) | 1155 (68%) | 0.003 |

| Admission medications | |||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 451 (46%) | 1007 (42%) | 1065 (36%) | 605 (36%) | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 98 (10%) | 253 (11%) | 318 (11%) | 144 (9%) | 0.080 |

| Beta blockers, any | 303 (31%) | 773 (33%) | 829 (28%) | 392 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Beta blockers, evidence based for heart failure | 208 (21%) | 467 (20%) | 464 (16%) | 209 (12%) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics, any | 703 (71%) | 1654 (69%) | 2119 (71%) | 1243 (73%) | 0.076 |

| Loop diuretics | 666 (67%) | 1533 (64%) | 1946 (65%) | 1146 (68%) | 0.140 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 113 (11%) | 191 (8%) | 193 (7%) | 81 (5%) | <0.001 |

| Potassium supplements | 396 (40%) | 861 (36%) | 1160 (39%) | 649 (38%) | 0.101 |

| Digoxin | 323 (33%) | 833 (35%) | 1054 (35%) | 686 (40%) | <0.001 |

| Nitoglycerine, sublingual | 124 (13%) | 330 (14%) | 438 (15%) | 242 (14%) | 0.373 |

| Nitrates, long-acting | 151 (15%) | 365 (15%) | 499 (17%) | 306 (18%) | 0.089 |

| Hydralizine | 58 (6%) | 151 (6%) | 159 (5%) | 59 (4%) | 0.001 |

| Nitrates and hydralazine | 12 (21%) | 59 (39%) | 69 (43%) | 20 (34%) | 0.020 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 89 (9%) | 288 (12%) | 367 (12%) | 147 (9%) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulant drugs | 213 (22%) | 528 (22%) | 723 (24%) | 320 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Statins | 205 (21%) | 466 (20%) | 438 (15%) | 100 (6%) | <0.001 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 137 (14%) | 374 (16%) | 525 (18%) | 309 (18%) | 0.007 |

| Tests and procedures | |||||

| Serum sodium, mEq/L (n=7871) | 138 (±4) | 138 (±5) | 139 (±5) | 138 (±6) | 0.186 |

| Serum potassium, mEq/L (n=7880) | 4.21 (±0.78) | 4.24 (±0.67) | 4.27 (±0.65) | 4.32 (±0.66) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mEq/L (n=7927) | 2.02 (±2.33) | 1.64 (±1.36) | 1.54 (±1.00) | 1.43 (±0.75) | <0.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, ml/min/1.73 m2 (n=7927) | 61 (±33) | 56 (±26) | 52 (±27) | 51 (±23) | <0.001 |

| Serum cholesterol, mg/dL (n=1201) | 179 (±57) | 172 (±49) | 169 (±48) | 168 (±47) | 0.095 |

| Serum albumin, gm/dL (n=4969) | 3.39 (±0.56) | 3.43 (±0.51) | 3.44 (±0.51) | 3.36 (±0.52) | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL (n=7887) | 28 (±21) | 27 (±17) | 29 (±18) | 29 (±16) | 0.008 |

| Serum glucose, mg/dL (n=7850) | 164 (±95) | 157 (±75) | 149 (±69) | 139 (±60) | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit, % (n=7684) | 38 (±7) | 37 (±6) | 36 (±6) | 36 (±6) | <0.001 |

| White blood cell, 109 cells per liter (n=7633) | 9 (±4) | 9 (±5) | 9 (±5) | 9 (±5) | 0.857 |

| Pulmonary edema by chest x-ray | 652 (66%) | 1577 (66%) | 2044 (69%) | 1191 (70%) | 0.020 |

Table 2.

Hospital and care characteristics by age

| n (%) or mean (±SD) | <65 years (n=991) | 65–74 years (n=2382) | 75–84 years (n=2978) | ≥85 years (n=1698) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural hospital | 285 (29%) | 704 (30%) | 917 (31%) | 606 (36%) | <0.001 |

| Hospital size | |||||

| <100 beds | 178 (18%) | 467 (20%) | 603 (20%) | 436 (26%) | <0.001 |

| 100–299 beds | 280 (28%) | 789 (33%) | 1049 (35%) | 588 (35%) | |

| 300–499 beds | 318 (32%) | 699 (29%) | 841 (28%) | 419 (25%) | |

| ≥500 beds | 215 (22%) | 427 (18%) | 485 (16%) | 255 (15%) | |

| Hospital ownership | |||||

| Nonprofit | 318 (32%) | 719 (30%) | 997 (34%) | 585 (35%) | <0.001 |

| Proprietary | 232 (23%) | 642 (27%) | 825 (28%) | 470 (28%) | |

| Other | 441 (45%) | 1021 (43%) | 1156 (39%) | 643 (38%) | |

| Care by a cardiologist | 540 (55%) | 1359 (57%) | 1582 (53%) | 690 (41%) | <0.001 |

| Care in the intensive care unit | 48 (5%) | 93 (4%) | 118 (4%) | 53 (3%) | 0.161 |

| Events on admission | |||||

| Pneumonia | 162 (16%) | 447 (19%) | 654 (22%) | 407 (24%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 0 (0%) | 4 (0%) | 9 (0%) | 10 (1%) | 0.023 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 36 (4%) | 78 (3%) | 104 (4%) | 54 (3%) | 0.897 |

| Pressure ulcers | 40 (4%) | 101 (4%) | 174 (6%) | 148 (9%) | <0.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 6 (1%) | 6 (0%) | 12 (0%) | 15 (1%) | 0.029 |

| In-hospital events | |||||

| Pneumonia | 43 (4%) | 94 (4%) | 139 (5%) | 102 (6%) | 0.020 |

| Stroke | 4 (0%) | 5 (0%) | 9 (0%) | 5 (0%) | 0.802 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5 (1%) | 14 (1%) | 29 (1%) | 18 (1%) | 0.182 |

| Pressure ulcers | 14 (1%) | 42 (2%) | 92 (3%) | 68 (4%) | <0.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 (0%) | 6 (0%) | 4 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.421 |

Quality of Care

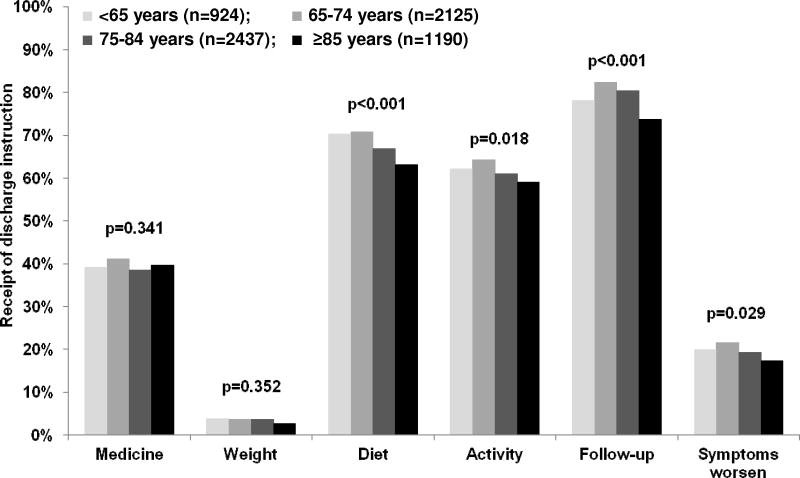

Overall, LVSF was evaluated in 69% of the patients, and 77% of the eligible patients with LVSD received a discharge prescription for ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Complete discharge instructions and smoking cessation counseling were provided to 1%, and 29% of patients respectively. A higher proportion of younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF received LVSF evaluation (72% versus 68%; p=0.015). However, except for those ≥85 years, older adults in general had similar rates of LVSF evaluation (Table 3). The rate of discharge prescription of ACE inhibitors or ARBs were also higher among younger eligible HF patients with LVSD (83% versus 76% for those ≥65 years; p=0.007). These rates were similar for the three older age categories (Table 3). Similarly, the rate proportion of eligible HF patients with LVSD who received a discharge prescription of beta-blocker was also higher among younger patients (40% versus 33%; p=0.007). There were no differences with respect to complete discharge instructions and smoking cessation counseling between age groups (Table 3). The distribution of the receipt of individual components of discharge instruction is displayed in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Quality of care by age

| Quality indicators (eligible patients) | <65 years | 65–74 years | 75–84 years | ≥85 years | Overall P value | P value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSF evaluation* (n=7867) | 706 (72%) | 1683 (72%) | 2035 (70%) | 983 (60%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs at discharge (n=2211) | 270 (83%) | 572 (77%) | 602 (75%) | 253 (75%) | 0.043 | 0.013 |

| Written discharge instructions (n=6586)** | ||||||

| All | 10 (1%) | 24 (1%) | 18 (1%) | 10 (1%) | 0.500 | 0.241 |

| Any | 843 (92%) | 1975 (93%) | 2228 (93%) | 1048 (92%) | 0.212 | 0.677 |

| Smoking cessation counseling (n=910)*** | 94 (32%) | 105 (29%) | 53 (24%) | 8 (21%) | 0.143 | 0.021 |

Includes past, present or planned for the future

Based on all patients discharged alive

Based on current smokers discharged alive and not discharged to hospice care

ACE =angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs=angiotensin receptor blockers; LVSF=left ventricular systolic function

Figure 1.

Receipt of individual written discharge instructions by age

Outcomes

During 9 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality occurred in 54%, 61%, 71% and 80% of patients <65, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years of age respectively (overall and trend p <0.001) (Figure 2 and Table 4). Proportions of events due to all-cause hospitalization, HF hospitalization, the combined end point of HF hospitalization or all-cause mortality, and the combined end point of all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality by age are displayed in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots comparing all-cause mortality by age

Table 4.

Outcomes by age

| Outcomes | <65 years (n=991) | 65–74 years (n=2382) | 75–84 years (n=2978) | ≥85 years (n=1698) | Overall P value | P value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 539 (54%) | 1454 (61%) | 2109 (71%) | 1353 (80%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 882 (89%) | 2104 (88%) | 2554 (86%) | 1365 (80%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure hospitalization | 641 (65%) | 1425 (60%) | 1643 (55%) | 805 (48%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 953 (96%) | 2289 (96%) | 2889 (97%) | 1653 (97%) | 0.076 | 0.020 |

| All-cause mortality or heart failure hospitalization | 847 (86%) | 2049 (86%) | 2646 (89%) | 1554 (92%) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Findings of the current study demonstrate that nearly half of the younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF were African American, a proportion which was nearly twice as high as that among older Medicare beneficiaries with HF. Younger HF patients also had a relatively higher burden of comorbidities and received care more often in large, urban hospitals. Although, the rate for LVSF evaluation was similar up to age 85, the rate of ACE inhibitor or ARB use declined after age 65 years. Younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF had lower all-cause mortality but higher hospitalization due to worsening HF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive report comparing baseline characteristics, quality of care and natural history of younger and older Medicare beneficiaries with HF.

The significantly higher proportion of African American among younger HF patients in our study may in part be explained by the early onset of HF among African American. HF among younger adults in the community is essentially HF among African American [10]. Findings from clinical trials of HF also suggest that compared to older HF patients, a significantly higher proportion of younger HF patients are African American [11–13]. An interesting observation of our study is that despite having a higher mean glomerular filtration rate, younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF also had a higher mean serum creatinine level. This is in contrast to the findings from HF patients in clinical trials [13]. This may in part be due to the higher proportion of African American and men among younger HF patients. Although renal failure is one of the criteria for Medicare eligibility for persons <65 years, those with renal failure were excluded from the AHFP registry.

The overall modest rates of LVSF evaluation and discharge use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs observed in our study are similar to previously reported rates based on contemporary HF registries [3, 4, 14]. The modest rate of ACE inhibitor or ARB use may in part be due to overestimation of the number of patients eligible for the receipt of these drugs based on chart abstracted data. For example, a patient with normal systolic blood pressure not receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs would be considered eligible, yet his/her physician may have discontinued those drugs to correct hypotension, which is known to be associated with poor outcomes in HF [15–17]. Because many of the current HF quality indicators may not be associated with improved outcomes, it has been suggested that future quality measures should be restricted to accountability measures or those associated with improved outcomes [18, 19]. The higher HF hospitalization in older HF patients may in part be explained by their lower mortality. Further, older HF patients often attribute their HF symptoms to aging and avoid seeking care.

Our study has several limitations. We had no data on qualifying disability for younger Medicare beneficiaries. If younger adults with HF were eligible for Medicare benefits based on the advanced nature of their HF, they would likely not be representative of younger HF patients in the community. Future studies need to compare younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF with younger HF patients who are not Medicare beneficiaries. We also had no data on patient and physician preferences, and insurance status, which may explain part of the age-related variation in quality of care. Although we only had data on fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, during the AHFP study period, between 80% and 87% of all Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in a fee-for-service plan.

In conclusion, younger Medicare beneficiaries with HF are characterized by a disproportionate higher proportion of African American, who generally receive better quality of care and had a lower total mortality but had higher re-hospitalization due to HF.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Ahmed is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants (R01-HL085561, R01-HL085561-S and R01-HL097047) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama

The authors of this manuscript have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical Publishing in the International Journal of Cardiology [20].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havranek EP, Masoudi FA, Westfall KA, Wolfe P, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Spectrum of heart failure in older patients: results from the National Heart Failure project. Am Heart J. 2002;143:412–7. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–1999 to 2000–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:305–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathore SS, Foody JM, Wang Y, et al. Race, quality of care, and outcomes of elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289:2517–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed A, Allman RM, DeLong JF, Bodner EV, Howard G. Age-related underutilization of left ventricular function evaluation in older heart failure patients. South Med J. 2002;95:695–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed A, Allman RM, DeLong JF, Bodner EV, Howard G. Age-related underutilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in older hospitalized heart failure patients. South Med J. 2002;95:703–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A, Allman RM, Kiefe CI, et al. Association of consultation between generalists and cardiologists with quality and outcomes of heart failure care. Am Heart J. 2003;145:1086–93. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(02)94778-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed A, Maisiak R, Allman RM, DeLong JF, Farmer R. Heart failure mortality among older Medicare beneficiaries: association with left ventricular function evaluation and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use. South Med J. 2003;96:124–9. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000051271.11872.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed A. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with heart failure and renal insufficiency: how concerned should we be by the rise in serum creatinine? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1297–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1179–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew J, Wittes J, McSherry F, et al. Racial differences in outcome and treatment effect in congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:968–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahle C, Adamopoulos C, Ekundayo OJ, Mujib M, Aronow WS, Ahmed A. A propensity-matched study of outcomes of chronic heart failure (HF) in younger and older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Age- and gender-related differences in quality of care and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure (from OPTIMIZE-HF) Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai RV, Banach M, Ahmed MI, et al. Impact of baseline systolic blood pressure on long-term outcomes in patients with advanced chronic systolic heart failure (insights from the BEST trial) Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:221–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2217–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller M, et al. Relation of Baseline Systolic Blood Pressure and Long-Term Outcomes in Ambulatory Patients with Chronic Mild to Moderate Heart Failure American Journal of Cardiology. Am J Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson ME, Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, et al. Process of care performance measures and long-term outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Med Care. 2010;48:210–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca3eb4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures–using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:683–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1002320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shewan LG, Coats AJ. Ethics in the authorship and publishing of scientific articles. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:1–2. [Google Scholar]