Langerhans cells (LCs) represent the main antigen capturing, processing and presenting dentritic cells (DCs) resident in epithelial surfaces including the skin or the oral mucosa, thus leading to either the induction of immune responses or tolerance. They are classically considered as myeloid-derived DCs sharing initial steps of their differentiation with monocytes. LC histiocytosis (LCH) and the more aggressive variant LC sarcoma (LCS) are considered as the neoplastic counterparts of this DC cell type. The immunoreactivity for macrophage-associated antigens in conjunction with CD1a, S-100 protein and langerin (CD207) represents a useful tool to establish the diagnosis of LCH in paraffin-embedded material.1 Rare cases of neoplasms with LC differentiation features developing in patients previously diagnosed with follicular lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukaemia (ALL) of T- and B-cell lineage have been reported. In these cases, identical clonal IgH- or TCRγ-gene rearrangements were detected in the H/DC neoplasms and the lymphomas consistent with a common clonal origin.2, 3, 4, 5 The development of the histiocytic dentritic/cell (H/DC) neoplasm was associated with progressive disease in most of these cases. Thus, it has been suggested that these tumours may represent a part of the clonal evolution of the underlying lymphomas.4 The development of a LCS in a patient with an acute B-ALL in complete remission for 9 years has been attributed to a transcription factor-induced transdifferentiation.5 Both neoplasms showed an identical IgH rearrangement, but different expressions of PAX5 and ID2.5

Only rarely, an association of LCH and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) has been reported. In most of these cases, the AML developed subsequently to LCH and this was considered as a therapy-related leukaemia.6 Here, we describe a concomitant occurrence of LCH and a myeloid sarcoma (MS) characterized by the presence of the same chromosomal aberration (trisomy 8) in both populations.

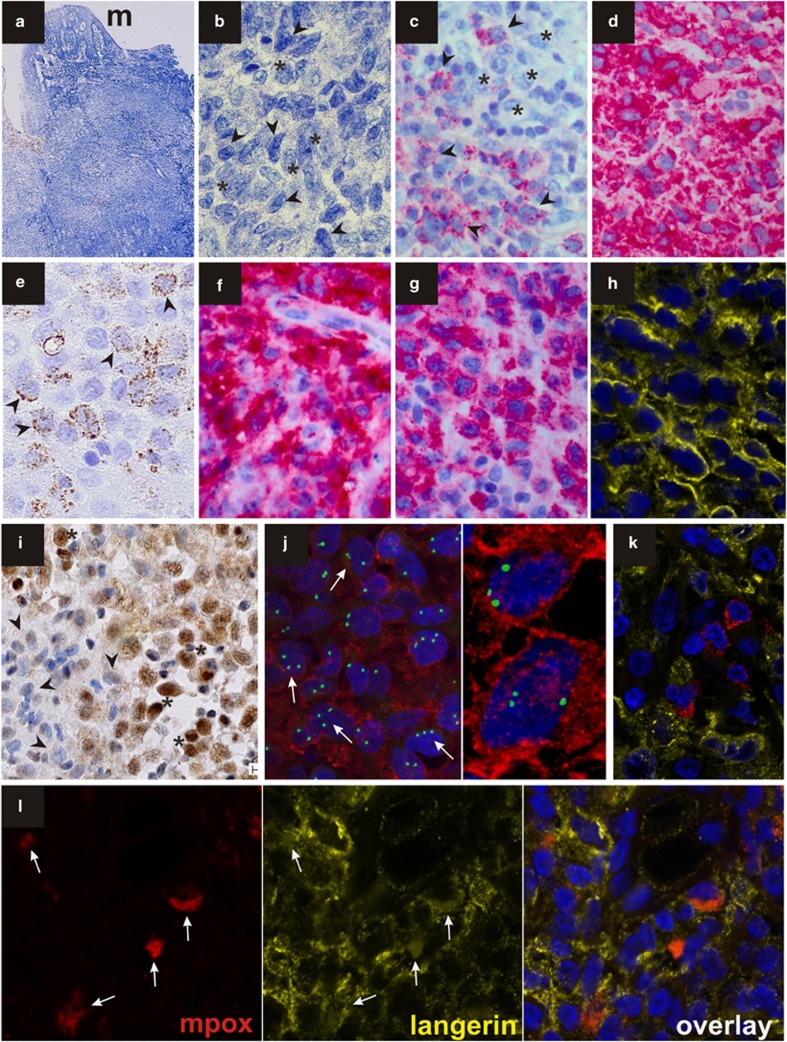

A 61-year-old woman was seen by her dental surgeon because of an enlarging gingival mass. An excisional biopsy measuring 1.3 cm in diameter was performed at region 26 and submitted by the referring pathologist for consultation to the Berlin Reference Centre for Lymphoma and Hematopathology. The patient had been well without a significant past medical history until approximately 3 months earlier when fatigue and anaemia developed. A bone marrow aspirate with 7% myeloblasts and an isolated trisomy 8 were consistent with a refractory anaemia with blast excess-1 (RAEB-1). As her clinical and haematological conditions appeared stable, she was monitored without therapeutic intervention. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsy of the oral mucosa (Figure 1a) showed a tumour-forming infiltration by mononuclear cells with heterogeneous morphological and immunophenotypic features. Sheets of medium- to large-sized cells with grooved nuclei and a pale cytoplasm (Figure 1b, asterisks) with a low mitotic activity were intermingled with smaller monomorphic blast cells with basophilic cytoplasms and oval-shaped or slightly folded nuclei (Figure 1b, arrowheads). On immunohistological examination, the smaller blasts had higher mitotic counts and were positive for myeloperoxidase (Figure 1c), CD33 (Figure 1d), CD68 in a finely granular staining pattern (Figure 1e), partially for CD34 and showed a trisomy 8 when examined by FISH. The larger-sized cells (asterisks) were negative for myeloperoxidase (Figure 1c), CD34, CD3, CD20 and CD30 but strongly expressed CD1a (Figure 1f), protein S100, langerin (CD207, Figures 1g and h) and Id2 (Figure 1i). Combined immunolabelling (FICTION) with a langerin antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK) and interphase cytogenetics by FISH with a CEP 8 spectrum green direct-labelled fluorescent DNA probe kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) was performed. FICTION provided evidence that trisomy 8 and langerin expression were both harboured by identical cells (Figure 1j). In addition, confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM) revealed the presence of myeloperoxidase-positive myeloid blasts (red) among the langerin-positive LCH cells (LCHC; yellow; Figures 1k, l). A subpopulation of neoplastic cells coexpressed myeloperoxidase and langerin suggestive of a mixed myeloid/LC phenotype (Figure 1l). The findings are consistent with a simultaneous manifestation of LCH and MS of myelomonocytic type. Interestingly, we observed a strong nuclear immunolabelling for the Id2 protein in the LCH component of the lesion, whereas the myeloid blasts appeared largely negative (Figure 1i). At this time, the patient's peripheral blood showed anaemia (hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL), a white cell count of 4 × 109/l without evidence of blasts and a normal platelet count of 275 × 109/l. However, 1 month later, overt AML developed with 39% bone marrow blasts and peripheral hyperleucocytosis (78 × 109/l). On flow cytometric analysis, the bone marrow blasts expressed HLA-DR, CD11b, CD13, CD14 and CD33 and partially CD34, which was consistent with a myelomonocytic phenotype. In contrast to the strongly CD1a-positive LCHC population observed in the gingival mass, bone marrow blasts were CD1a negative. Immunophenotyping for langerin was not performed on the bone marrow sample. Cytogenetics revealed the karyotype (46 XY, +8) both in the myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and the AML. Trisomy 8 was confirmed by FISH. No additional molecular genetic changes were detected. Induction chemotherapy with cytarabin, idarubicin and etoposide resulted in a transient cytoreduction, whereas bone marrow blasts rapidly increased and malignant pleural and pericardial effusions developed. A buccal swab was suggestive of malignant cells. Despite 5-azacytidine treatment the patient died of progressive disease 4 months after the initial manifestation of MS. No autopsy was performed.

Figure 1.

(a) Histologic aspect of the Giemsa-stained gingival biopsy characterized by a broad-based mass located beneath the oral surface mucosa (m). (b) Large LCHCs with grooved nuclei and pale cytoplasm (asterisks) as well as smaller blasts with oval or delicately folded nuclei and indistinct nucleoli (arrowheads) were observed (Giemsa). The blasts (arrowheads) expressed myeloperoxidase (c), CD 33 (d) and showed a finely granular CD68 staining (e). While LCHCs were negative for myeloperoxidase (c, asterisks) they were labelled by CD1a (f), langerin (g, h, confocal image) and Id2 (i) antibodies. By FISH analysis using a DNA probe for trisomy 8 (green) and immunstaining for langerin (red), a trisomy 8 (arrows) was clearly detected in LCHCs (j). CLSM imaging of double stains for myeloperoxidase (red) and langerin (yellow) showed the presence of scattered myeloperoxidase-positive blasts within the sheets of langerin-positive LCHCs (k). There was evidence of a rare coexpressions of both antigens in identical cells, which were stained both in red and in yellow (l; arrows).

An MS is defined as a mass of myeloid cells occurring in an extramedullary site previously, simultaneously or subsequently to an AML or a myeloproliferative neoplasm. It may be preceded by a MDS, as seen in our patient. In rare cases, an MS may represent the unique manifestation of a myeloid neoplasm without bone marrow involvement at any time of the disease. The evidence of a trisomy 8 in both the components of the oral mass lesion of our patient strongly supports the conclusion that these neoplsms were clonally related. In a large cohort of 92 cases of MS, Pileri et al.7 did not describe any LCH but identified foci of plasmacytoid monocyte differentiation within an obvious myeloid population in four cases. In two of theses cases, both the cellular components showed an opposite phenotype but belonged to the same clone. An inversion 16 was detected in the tumour-forming accumulations of plasmacytoid monocytes and in the myeloid population. This observation was in accordance with the hypothesis that the occurrence of plasmacytoid monocytes in the course of myeloid disorders may represent a differentiation of the underlying disorder. CLSM imaging of our case showed myeloperoxidase in conjunction with CD1a and langerin in a subpopulation of trisomy 8-positive tumour cells. This coexpression represents a phenotypic aberrancy consistent with a differentiation of myeloid blasts towards LCHCs in vivo. DCs can be generated from AML blasts in vitro but do not display typical morphological and immunophenotypic features of LCs.

The clonality of LCH has only rarely been assessed based on the on X-chromosomal inactivation mosaicism in somatic tissues and polymorphism of the androgen receptor gene in female patients.8 To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating a focus of LCH within an MS developing in the buccal mucosa where both neoplastic populations displayed the same cytogenetic abnormality, that is, trisomy 8, as the pre-existing myeloid disorder. Interestingly, trisomy 8 has been detected in 10.4% of MS studied by FISH in the series of Pileri et al.,7 suggesting that this aberrancy may be recurrently associated with the development of a MS. Noteworthy, FISH and cytogenetic analyses provided corresponding results in this study, confirming that FISH is a useful tool in cases where only formalin-fixed, but no fresh material is available. Unfortunately, our patient rapidly succumbed to her disease before allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation could be performed. This adverse outcome is in concordance with the data of Pileri et al.,7 suggesting that all of their MS patients with positive cytogenetics died of their disease irrespectively of their age or the type of their MS. By contrast to the unfavourable prognosis of MS, long-lasting responses have been obtained in adult LCH by multi-drug chemotherapy. Thus, rapid detection of phenotypic heterogeneity of tumour cells in biopsy specimens is mandatory for the choice of the best treatment modality. The factors responsible for the induction of a dichotomous phenotype in the trisomy 8-positive neoplastic cells of our patient are not yet understood. The high Id2 expression levels that we observed in the LCH component of our case suggests that a deregulation of this dominant negative helix-loop-helix transcription factor of the ID family may contribute to the commitment of haematopoietic precursors to an LC phenotype. An acquisition of Id2 and loss of PAX5 have been regarded as key factors in the transdifferentiation from a B-ALL to a LC/dentritic phenotype.5 Little is known about the mechanisms by which Id2 regulates myeloid development. It is conceivable that transcription factors of the bHLH protein and Ets protein families may act downstream of ID2 and modulate myeloid development and proliferation. The divergent differentiation patterns reported here represent another example of the plasticity of haematopoietic cells that could, at least in part, be mediated by transcription factors including ID2 and its target genes.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jaffe R, Weiss LM, Faccetti F.Tumours derived from Langerhans cellsIn: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H et al. (eds)WHO classification of tumours of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues IARC Press: Lyon; 2008358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Minniti C, Santi M, Downing JR, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Histiocytic sarcoma after acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a common clonal origin. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:248–250. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Berthold F, Arceci RJ, Abramowsky C, Shehata BM, Mann KP, et al. Clonal relationship between precursor T-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma and Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:435–437. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Arber DA, Pittaluga S, Martinez A, Burke JS, Raffeld M, et al. Clonally related follicular lymphomas and histiocytic/dendritic cell sarcomas: evidence for transdifferentiation of the follicular lymphoma clone. Blood. 2008;111:5433–5439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratei R, Hummel M, Anagnostopoulos I, Jähne D, Arnold R, Dörken B, et al. Common clonal origin of an acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia and a Langerhans′ cell sarcoma: evidence for hematopoietic plasticity. Haematologica. 2010;95:1461–1466. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.021212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeler RM, Neglia JP, Aricò M, Favara BE, Heitger A, Nesbit ME. Acute leukemia in association with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;23:81–85. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950230204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pileri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, Campidelli C, Bacci F, Piccioli M, et al. Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia. 2007;21:340–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Zhang WD, Li YH, Liu XY, Yao L, Han XJ, et al. Clonal status and clinicopathological features of Langerhanscell histiocytosis. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1099–1105. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]