Summary

Intra-arterial (IA) chemotherapy for malignant gliomas including glioblastoma multiforme was initiated decades ago, with many preclinical and clinical studies having been performed since then. Although novel endovascular devices and techniques such as microcatheter or balloon assistance have been introduced into clinical practice, the question remains whether IA therapy is safe and superior to other drug delivery modalities such as intravenous (IV) or oral treatment regimens. This review focuses on IA delivery and surveys the available literature to assess the advantages and disadvantages of IA chemotherapy for treatment of malignant gliomas. In addition, we introduce our hypothesis of using IA delivery to selectively target cancer stem cells residing in the perivascular stem cell niche.

Key words: glioblastoma multiforme, blood brain barrier, perivascular niche, superselective intra-arterial cerebral infusion, selective intra-arterial niche disruption

Introduction

Malignant gliomas, including the most fatal form glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), remain challenging to treat due to their unresponsiveness to therapy. The current standard multimodal treatment approach for GBM involves maximal surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy with concomitant administration of chemotherapeutic agents, such as temozolomide1,2. This regimen results in a median overall survival of only 15 months with a two-year survival rate of 26%3,4. However, patients with methylated MGMT (methylguanine methyltransferase) promoter have a higher median overall survival of 23.4 months with a two-year survival rate of 48.9%5. After recurrence, rapid tumor progression results in a median progression free survival and overall survival of only nine weeks and 25 weeks, respectively, despite reoperation and attempting new chemotherapeutic agents6. Even with our increasing knowledge of GBM molecular biology and new molecular drug targets, the current treatment options remain ineffective7. However, promising new drugs are being evaluated, and new techniques have improved drug delivery through the blood brain barrier (BBB)6,8,9. In addition, novel microcatheters and other endovascular assistance devices have been developed within the last several years, and selective intra-arterial cerebral infusion (SIACI) techniques allow for an even more focused delivery of chemotherapeutic agents with less systemic toxicity10-12. This review will critically analyze existing preclinical and clinical studies of IA chemotherapy for malignant gliomas by comparing the technique, agents, and inclusion criteria with the ultimate aim to provide a basis for improving future studies.

Historical Note on Intra-Arterial Delivery

IA delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs for the adjuvant treatment of retinoblastoma and hepatic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma is well-established and has been shown to provide survival benefit for patients13-15. IA therapy for malignant brain tumors and especially, high-grade gliomas has been administered since the 1950s and 1960s after the blood brain barrier (BBB) was described16,18. In 1921, Stern and Gautier noted at autopsy that the brain of jaundice patients was not yellow like the rest of the body´s organs and hence the existence of the BBB was found. Klopp et al. and French et al. were the first to use and publish on IA chemotherapy for progressive malignant gliomas in humans and animals using intracarotid approaches18,19. Klopp et al. in 1950 demonstrated that administration of a nitrogen mustard in repeated amounts lead to tumor regression in rabbits with extracranial xenografts19. However, in 1952, French et al. failed to show that nitrogen mustard delivered through a carotid approach had a therapeutic effect on patients and its delivery was associated with neurotoxicity. Several other IA attempts followed, but objective direct comparisons with the IV administration were not performed. The advantages of IA drug administration were assessed in detail by Eckman et al. showing that IA infusion led to a higher tumor drug exposure compared to non-targeted tissue20. In the 1970s, Rapoport et al. and Neuwelt et al. began to improve IA drug delivery through the BBB by analyzing the effects of iatrogenic osmotic BBB disruption (BBBD) to increase the BBB's permeability21,22. Rapoport et al. discovered the following: 1) barrier opening is reversible and is an all or nothing phenomenon occurring at high osmolality; 2) the osmotic agent acts independently of any specific drug, and 3) does not affect BBB endothelial cell membrane permeability directly, but rather the intercellular permeability. Multiple IA and BBBD studies followed, utilizing the “Seldinger technique”23 in which microcatheters were threaded into the arterial vessels supplying the brain.

Selective Intra-Arterial Cerebral Infusion

Due to the development of novel drugs and the emergence of new selective microcatheters and other endovascular devices, the IA technique has been actively revisited within recent years. The selective intra-arterial cerebral infusion (SIACI) technique requires a catheter, which is inserted into the femoral artery and ends in the carotid artery, and a separate microcatheter, inserted via the femoral catheter is used to selectively explore the vessels of interest. The insertion of the catheters in the angiographic suite is usually conducted with guidewire assistance and road-mapping control. In human trials, the SIACI technique allows for accurate and super selective targeting of the tumor's supplying vessels11,12,17. This is a remarkable advantage not seen with unselective IA infusion such as carotid or vertebral infusion, because the novel microcatheters allow a super selective exploration of specific cerebral vessels while potentially limiting neurotoxicity24. However, a higher drug-level in the corresponding brain region is not necessarily guaranteed because heterogeneous drug delivery may occur during chemotherapeutic delivery25. Heterogeneous delivery results in the infused drug being mixed insufficiently, and one arterial branch may be bypassed over another26. Gobin et al. developed a concept of regional dosage based on the vascular territories using a spatial dose fractionation algorithm with a pulsatile delivery method25. With the help of this algorithm, the needed agent dose can be calculated based on the vascular perfusion of the vessel and may optimize IA drug delivery. Consequently, neurotoxicity as well as heterogeneous drug delivery can be minimized25,27.

Osmotic Blood Brain Barrier Disruption for Enhanced Drug Delivery

A critical factor in IA drug delivery is the function of the BBB, since this barrier limits the uptake of molecules with a threshold of approximately 400-600 Daltons into the brain tissue28. The uptake of higher molecular weight agents, such as monoclonal antibodies, which can be 150,000 Daltons, is even further diminished. Preclinical21,29-33 and clinical studies28,34,35 have shown that the BBB function can be reversibly modified to be more permeable leading to a significantly higher uptake of intra-arterially delivered drugs compared to the non-altered BBB36. For instance, hypertonic solutions such as mannitol can be used to reversibly increase cerebrovascular permeability11,28,37-40. Rapoport et al. in 1980 investigated the necessary infusion time and concentration for disruption of the BBB, and reported this threshold to be 1.4 molar of infusate for 30 seconds of infusion or 1.0 molar for two minutes, respectively31. Optimum BBBD as measured by Evans Blue Dye was achieved in rats infused intra-arterially with mannitol at 0.09 to 0.12 mL/s41. However, in humans, hypertonic solutions need to be used more judiciously to avoid severe side-effects such as seizures and brain edema34. Since individual factors need to be taken into account, an exact formula of the concentration and infusion time is difficult to determine. In addition, the discrepancy of brain size between humans and rats (1200 g versus 1 g respectively) makes it difficult to implement preclinical results into human trials. In our experience using SIACI, a mannitol infusion rate of 0.083 mL/s for 120 seconds showed no associated morbidity or mortality12 and induced an angiographically visible hypervascular blush after mannitol infusion and application of a contrast agent28,42.

Intra-Arterial Cerebral Infusion of Chemotherapeutic Drugs

Obtaining preclinical data before initiating human trials is the norm in medicine to evaluate novel techniques. However, the turnover from preclinical to clinical studies in IA therapy was nearly instantaneous in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme19. The reason for the rapid turnover might be due to the need for new promising treatment options to alleviate this dismal disease and the challenge to find a suitable and predictive preclinical model. In 1951, the first heterotransplantations of human brain tumor tissue into animals were done43,44. However, attempts to implant and grow human tumors in the brains of animals have been inconsistent and not improved until the athymic nude mouse was successfully established in 196845. This allowed for the study of the growth and behavior of tumor xenografts in vivo under controlled conditions46,47.

Preclinical studies

Neuwelt et al. started to use these athymic rodent brain tumor models to assess IA administration of drugs with and without BBBD32,48,49. For instance, a study on nude rats with human tumor xenografts showed that IA administration of melphalan increased the tissue concentration of the agent up to fourfold in the tumor and up to 20 times in the surrounding area compared to IV administration48. These results agree with a previous animal study using radiolabled agents to determine the pharmacokinetics of IA infusion. Levin et al. determined that the concentration of BCNU in the IA targeted brain tissue was 2.8 times higher compared to IV administration50. In 1996, Hassenbusch et al. also confirmed the efficiency of IA infusion by treating normal brains of New Zealand White rabbits with BCNU51. With their findings, Neuwelt et al. demonstrated that nude rat provides the appropriate structural requirements to analyze IA therapy since they accept xenografts, are less susceptible to infections compared to nude mice, and are easier to maintain. However, the nude rat does not provide as good a growth medium for tumor xenografts compared to the mouse48. In multiple preclinical studies, different agents were tested, and a variety of clinical questions were addressed with regard to these xenograft rat models. For instance, Schuster et al. showed that IA delivery of 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide in athymic rats with glioma xenografts substantially increased the tumor drug levels and survival rates compared to IV delivery52. Melphalan was found to have a statistically significant effect in anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma multiforme in rat models after IA administration53 and Remsen et al. analyzed the effect of IA carboplatin and melphalan with BBBD compared to animals previously treated with radiation and demonstrated a significant decrease in drug delivery after radiation54. However, melphalan did not show significant therapeutic effectiveness in human trials for malignant gliomas, although IA melphalan shows promising results in the treatment of intracranial lymphomas and retinoblastoma40. Boyel et al. infused vincristine transcarotically without BBBD and documented a lack of penetration of this agent in the post mortem brain tissue. Since vincristine is a small (molecular weight of 930) and lipophillic drug, it should result in a higher penetration through the BBB, which has been shown to pass lipophillic molecules with molecular weight of up to 65,000. In a 2009 study, sunitinib, a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was combined with temozolomide for the treatment of brain tumor xenografts in rats. Zhou and Gallo showed a significant increase of temozolomide concentration in brain tissue when combined with low dose sunitinib compared to high dose of sunitinib and temozolomide alone using IA administration55. However, this paper did not focus on the IA technique, and a proper IA treatment plan was not specified in the paper.

In summary, rodent animal models have been established within the last decade to further investigate IA infusion for malignant gliomas. However, one of the main pitfalls is the lack of a specified and consistent IA technique in these preclinical models. Rodent intracerebral IA infusion techniques use either the internal carotid artery through the external carotid artery by catheterization or by a direct puncture of the internal carotid artery with a cannula. Zink et al. recently developed selective microcatheters for rats, which can be either placed selectively into the internal carotid artery supplying a unilateral cerebral hemisphere or only into the supplying branches of the hypothalamus and lateral thalamus56. These catheters can be used in animals harboring brain tumor xenografts to test selective IA delivery. Recent success with rabbit models also holds promise for the effective pre-clinical testing of IA delivery.

Clinical studies

Patients with newly diagnosed as well as recurrent high-grade gliomas have been evaluated in the last few decades in several trials of IA and IV chemotherapy as well as in combined treatment strategies17,38,39,57 with either single-agent58,59 or combined chemotherapeutic regimens60,61 (Table 1). Both administration routes were used as an adjuvant treatment only after attempted surgical resection in combination with or after radiation therapy. While IV chemotherapy is usually repetitively administered depending on the treatment plan, the IA application has been more likely given as a single-dose following another single repetition as needed or as an IV continuation12,25,39,62. Inclusion criteria for patients participating in IA trials include patients who have undergone surgery and who are in a favorable clinical condition. While some studies have included patients with a Karnofsky performance scale score (KPS) of 2039, the vast majority of clinical trials require a KPS of at least 6025,38.

Table 1.

Summary of intra-arterial chemotherapy studies involving patients with malignant gliomas.

| Study | Included Tumor Entities |

No. of Pa- tients1 |

Study Type | Intra- Arterial Delivery2 |

Intra- Arterial Chemotherapeutic Agent |

Intra- Arterial BBBD Agent |

Tumor Repons | Neurotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doolittle et al.(2000) |

GBM, BSG, aO, O, MET, GCT PCNSL, PNET, |

221/126 | MC, Phase II | C, V | Carboplatin | Mannitol | 79% SD or better | Stroke (0.93%) and Herniation (1.2%) |

| Chow et al. (2000) |

rGBM, aOA, aA | 46/46 | SC, Phase II | S | Carboplatin | Cereport (RMP-7) |

32% SD or better, PFS 3 mo |

– |

| Kochii et al. (2000) |

nGBM | 42/42 | MC, Phase II* | C, V | Nimustine (ACNU) | – | MST 17 mo/16 mo* and PFS 6 mo/11 mo* |

Reversible Vision Loss (2.4%) |

| Madajewicz et al. (2000) |

GBM, aA | 83/83 | SC, Phase II | C, V | Etoposide and Cisplatin | – | 48% PR or better and MST 18mo |

Blurred Vision (48%) and Focal seizure (6%) |

| Ashby and Shapiro (2001) |

rGBM, aA, aO, aOA |

25/25 | SC, Phase II | C, V | Cisplatin | – | 40% SD or better and PFS 4.5 mo |

Headache, Increased Seizure Frequency, and Encephalopathy (45%) |

| Gobin et al. (2001) |

GBM, aA, MET, NS |

113/93 | SC, RS | S | Carboplatin | Lobradimil | – | Seizures (7%) and Major Neurologic Detoriation (<0.6%) |

| Qureshi et al. (2001) |

GBM, aA, A, aOA, MET |

24/24 | SC, RS | S | Carboplatin | Cereport (RMP-7) |

– | Transient Neurologic Deficits (20%) and Stroke (4%) |

| Newton et al. (2002) |

aA, aOA, aO, O, BSG, ME |

25/12 | SC, Phase II | C, V | Carboplatin | – | 80% SD or better and PFS 6 mo |

Transient Ischemic Attack (8%) |

| Silvani et al. (2002) |

nGBM | 15/15 | SC, Phase II* | C, V | Carboplatin and Nimustine (ACNU) |

– | 78,6%/66% SD and PFS 5.2 mo/5.8 mo* |

Seizures (6.6%) and Intracerebral Hemorrhage (6.6%) |

| Fortin et al (2005) |

GBM, aA, aO, MET, PNET, PC- NSL |

72/48 | SC, Phase II | C, V | Carboplatin | Mannitol | MST 9.1 mo and PFT 4.1 mo |

– |

| Imbesi et al. (2006) |

nGBM | 17/17 | SC, Phase III* | C, V | Nimustine (ACNU) | – | 59%/44%* SD or better and PFS 6 mo/4 mo* |

Stroke (5.6%) |

| Guillaume al. (2010) |

aO, aOA | 13/13 | SC, Phase I | C, V | Carboplatin and Melphalan | Mannitol | 77% SD or better and PFS 11 mo |

Speech Impairment (7.7%) and Retinopathy (7.7%) |

| Boockvar et al. (2010) |

GBM, aA, aO, | 30/28 | SC, Phase I | S | Bevacizumab | Mannitol | – | Seizures (6.6%) |

|

GBM Glioblastoma multiforme, n newly diagnosed, r recurrent, BSG brainstem glioma, a anaplastic, O oligodendroglioma, A astrocytoma, OA oligoastrocytoma, MET metastasis, PCNSL primary CNS lymphoma, PNET primitive neuroepithelial tumor, GCT germ tumor, ME malignant ependymoma, NS not further specified, 1 total patients / patients with malignant glioma including GBM, BSG, aO, aOA, aA; 2 S selective into the supplying tumor vessels, C unselective into the internal carotid artery or V the vertebral artery; *comparison of intra-arterial / intra-venous application; SC single-centre; MC multi- centre; SD stable disease; PR partial response; PFS progression free survival; MST median survival time. | ||||||||

Nitrosurea derivates such as carmustine (BCNU) or nimustine (ACNU), platinum analogs (cis- and carboplatin), methotrexate, vincristine or novel antibodies such as bevacizumab have hitherto been tested only for their safety and efficacy in humans IA trials. Although IA nitrosurea derivatives seemed to be promising in the first human studies63,64, the enthusiasm decreased in the 1990s due to neurotoxicity in the IA-treated patients. For instance, in 1986, Feun et al. suggested in their follow-up phase II trial that IA BCNU may cause severe leukoencephalopathy and blindness in the treated patients65. These findings were confirmed by Tonn et al. and Kleinschmidt-DeMasters et al. showing evidence for a higher risk of local cerebral necrosis as well as leukoencephalopathy in treated patients66,67. Finally, it was Shapiro et al. who concluded in their randomized phase III trial comparing IA with IV BCNU that IA BCNU is neither safe nor effective in prolonging patient survival60. Serious toxicity was observed in the IA-treated group including irreversible encephalopathy (9.5%) and ipsilateral visual loss (15.5%). These findings led to a decreased use of IA nitrosurea derivatives in future studies.

In contrast, platinum analogs showed fewer cerebral side effects in IA use10,27. Neurotoxicity such as retinopathy was rare, especially after the introduction of selective IA infusion, which spares the ophthalmic artery. Manageable extracerebral side-effects such as myelosuppression or gastrointestinal disturbance were observed after IA carbo-/cisplatin infusion 68. Follézou et al. showed that carboplatin achieved a partial response in malignant glioma patients using a dose of 400 mg/m2,68, Clocchlatti et al. showed a 74% response rate after 250 mg/m2 IA carboplatin infusion69 and Gobin et al. increased the carboplatin dose up to 1400 mg/hemisphere in their dose-escalation study based on cerebral blood flow27.

Using a selective intra-arterial pulsatile delivery via modern microcatheters and based on the local cerebral blood-flow estimation, the doses were escalated from 200 mg/hemisphere in 50 mg increments, and only one patient had a permanent neuromotor decline27. Newton et al. demonstrated that IA carboplatin with IV etoposide had modest efficacy against recurrent gliomas with a median overall time to progression of 24.2 weeks and 32 weeks time to progression in the responsive group (20% of all patients).

The overall median survival was 34.2 weeks in this study70. Some multicenter studies had difficulty assessing the treatment success of carboplatin alone, since in each of these study patients had a variety of intracranial tumor pathologies and were treated with more than one IA drug38,39,71.

In summary, clinical IA trials using nitrosureas and platinum analogs have been shown to be safe, and side-effects are mostly reversible and manageable. However, the efficacy of IA delivery of these agents is still not evident. For intracerebral lymphomas clinical trials have shown a benefit after IA methotrexate delivery40. However for the treatment of malignant gliomas standardized prospective phase III trials are needed to further assess the efficacy of these IA agents. Furthermore, novel agents, which are used in standard IV chemotherapy, need to be verified using IA delivery.

Future Directions: Targeted Agents and the Perivascular Cancer Stem Cell Niche

Novel targeted agents such as bevacizumab or cetuximab were recently introduced into clinical practice. Bevacizumab in combination with irinotecan has become the standard IV treatment for recurrent malignant gliomas72. Although a reasonable response rate within the first few months after bevacizumab treatment was detected on neuroradiological post-treatment studies, patient survival did not significantly improve73. Many studies address this issue of “pseudoresponse”74. A possible reason of the lack of response may be found in the fact that bevacizumab is not sufficiently delivered through the BBB. The BBB pore size in malignant solid tumors has recently been determined to be about 12 nm75 and bevacizumab with its size of 15 nm may be too large to penetrate through the BBB (personal communication, Moonsoo Jin, structural biologist, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA). Brain tumor stem-like cells (also called cancer stem cells) have been shown to be present in the perivascular niche and are thought to be the critical cells in tumor progression and recurrence. These cancer stem cells (CSCs) are known to secrete VEGF ligand and to express the VEGFR-2 receptor. Calabrese et al. showed that bevacizumab affects CSCs directly by inhibiting their ability of self-renewal leading to an arrest of brain tumor growth in mice76. Wang et al. recently showed that glioblastoma CSCs may differentiate into endothelial cell progenitors, which in turn become more mature endothelial cells77. The transition from endothelial cell progenitor to a mature endothelial cell was abrogated by bevacizumab therapy77. Therefore, we hypothesize that an increase in the concentration of bevacizumab in this extravascular space may increase the therapeutic effect by inhibiting CSC - endothelial cell VEGF signaling in addition to its effect on intravascular VEGF. We propose that IA delivery with BBBD may be an ideal method to enter the extravascular space/perivascular niche. IA delivery with BBBD would allow for selective intra-arterial niche disruption (SIAND) and delivery of desired agents such as bevacizumab or cetuximab, which may not be able to pass the BBB due to its size12. We hypothesize that by using reversible BBBD with mannitol followed by SIACI of bevazicumab, VEGF-dependent CSCs in the perivascular niche would be exposed to a higher bevacizumab concentration than by standard IV therapy. With reclosing of the BBB, bevacizumab remains in the area of interest and binds to VEGF that remains in the niche and acts on neighboring cells in an autocrine and paracrine fashion (Figure 1). In our phase I trial with IA bevacizumab after BBBD, we showed that IA bevacizumab is safe up to a dose of 15 mg/kg12,78-80. An ongoing phase II trial aims to assess the therapeutical effectiveness of repeated IA bevacizumab therapy. In addition, clinical trials with other agents to treat malignant gliomas such as temozolomide (temodar, Merck) (Figure 2) and cetuximab (erbitux, ImClone Systems, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck) have been initiated at our center using the SIAND approach.

Figure 1.

Sketch of our hypothesis on selective intra-arterial niche disruption (SIAND) and delivery A) Initially the BBB is closed and tumor stem-like cells located in the perivascular niche release VEGF and express VEGFR-2 receptors. B) The microcatheter is placed in the tumor supplying vessel and mannitol followed by bevacizumab is infused through the microcatheter. This opens the BBB and bevacizumab is able to enter into the perivascular niche to bind soluble VEGF. C) After IA treatment the BBB recloses and bevacizumab is trapped in the perivascular niche. VEGF signaling from tumor cells is blocked and VEGF signaling is diminished.

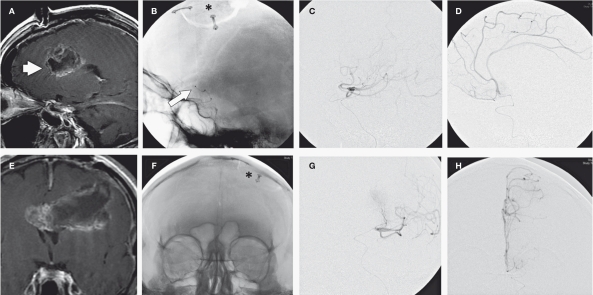

Figure 2.

Sagittal (A) and coronal (E) post-gadolinium T1W images show a large left fronto-temporal located glioblastoma multiforme (arrow) in a 72-year-old man. On the un-subtracted DSA (B, F) the microcatheter tip (arrow) with regard to the craniotomy site (asterisk) indicates the point of chemotherapy injection. Contrast infusion into the distal branch of the left middle cerebral artery (C, G) as well as left anterior cerebral artery (D, H) supplying the GBM demonstrates the distribution of IA mannitol and temozolomide infusion in sagittal (C, D) and coronal (G, H) planes.

Conclusion

In the hands of an experienced team, IA chemotherapy has been demonstrated to be a safe procedure with potential therapeutic benefits for malignant gliomas, although it has not been proven to be superior to the standard IV treatment of recurrent GBM. Since the introduction of selective IA chemotherapy with the use of selective microcatheters, the associated vascular and neurologic side-effects have significantly improved.

However, the paucity of phase III trials of IA chemotherapy precludes any meaningful interpretation of the efficacy of previous trials. Future trials will help us predict the efficacy and therapeutic value of IA therapy. Better preclinical modeling will better quantify pharmacokinetics, as well as optimize dosages for both BBBD and for selective IA delivery in animal models of brain tumors. Radiolabeled drugs will likely play a role in obtaining this important information. Using selective intra-arterial niche disruption (SIAND) and delivery to reach brain tumor stem-like cells in the perivascular niche still needs further study in both the pre-clinical setting and in human clinical trials to ascertain if the IA method provides a modality of accessing and treating resistant CSCs cells in malignant brain tumors.

References

- 1.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andratschke N, Grosu AL, Molls M, et al. Perspectives in the treatment of malignant gliomas in adults. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3541–3550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefranc F, Rynkowski M, DeWitte O, et al. Present and potential future adjuvant issues in high-grade astrocytic glioma treatment. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2009;34:3–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-78741-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieder C, Adam M, Molls M, et al. Therapeutic options for recurrent high-grade glioma in adult patients: recent advances. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bidros DS, Vogelbaum MA. Novel drug delivery strategies in neuro-oncology. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desjardins A, Rich JN, Quinn JA, et al. Chemotherapy and novel therapeutic approaches in malignant glioma. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2645–2668. doi: 10.2741/1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Khan J, et al. Superselective intra-arterial carboplatin for treatment of intracranial neoplasms: experience in 100 procedures. J Neurooncol. 2001;51:151–158. doi: 10.1023/a:1010683128853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riina HA, Fraser JF, Fralin S, et al. Superselective intraarterial cerebral infusion of bevacizumab: a revival of interventional neuro-oncology for malignant glioma. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2009;8:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boockvar JA, Tsiouris AJ, Hofstetter CP, et al. Safety and maximum tolerated dose of superselective intraarterial cerebral infusion of bevacizumab after osmotic blood brain barrier disruption for recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:624–632. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.JNS101223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liapi E, Geschwind JF. Intra-arterial therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: where do we stand. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1234–1246. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0977-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields CL, Shields JA. Retinoblastoma management: advances in enucleation, intravenous chemoreduction, and intra-arterial chemotherapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:203–212. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328338676a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramson DH, Dunkel IJ, Brodie SE, et al. Superselective ophthalmic artery chemotherapy as primary treatment for retinoblastoma (chemosurgery) Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1623–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens G, Javid R, Belmusto L, et al. Intra-arterial vincristine therapy of primary gliomas. Cancer. 1965;18:756–760. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196506)18:6<756::aid-cncr2820180613>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton HB. Intra-arterial chemotherapy of primary brain tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2005;6:519–530. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French JD, West PM, Von Amerongen FK, et al. Effects of intracarotid administration of nitrogen mustard on normal brain and brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 1952;9:378–389. doi: 10.3171/jns.1952.9.4.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klopp CT, Alford TC, Bateman J, et al. Fractionated intra-arterial cancer; chemotherapy with methyl bis amine hydrochloride; a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1950;132:811–832. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195010000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckman WW, Patlak CS, Fenstermacher JD, et al. A critical evaluation of the principles governing the advantages of intra-arterial infusions. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1974;2:257–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01059765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapoport SI, Hori M, Klatzo I, et al. Testing of a hypothesis for osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1972;223:323–331. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuwelt EA, Maravilla KR, Frenkel EP, et al. Osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption. Computerized tomographic monitoring of chemotherapeutic agent delivery. J Clin Invest. 1979;64:684–688. doi: 10.1172/JCI109509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seldinger SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol. 1953;39:368–376. doi: 10.3109/00016925309136722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riina HA, Knopman J, Greenfield JP, et al. Balloon-assisted superselective intra-arterial cerebral infusion of bevacizumab for malignant brainstem glioma. A technical note. Interventional Neuroradiology. 2010;16:71–76. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gobin YP, Cloughesy TF, Chow KL, et al. Intraarterial chemotherapy for brain tumors by using a spatial dose fractionation algorithm and pulsatile delivery. Radiology. 2001;218:724–732. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr41724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saris SC, Blasberg RG, Carson RE, et al. Intravascular streaming during carotid artery infusions. Demonstration in humans and reduction using diastole-phased pulsatile administration. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:763–772. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.5.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cloughesy TF, Gobin YP, Black KL, et al. Intra-arterial carboplatin chemotherapy for brain tumors: a dose escalation study based on cerebral blood flow. J Neurooncol. 1997;35:121–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1005856002264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwadate Y, Namba H, Saegusa T, et al. Intra-arterial mannitol infusion in the chemotherapy for malignant brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1993;15:185–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01053940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bullard DE, Bigner DD. Blood-brain barrier disruption in immature Fischer 344 rats. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:743–750. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.4.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiueh CC, Sun CL, Kopin IJ, et al. Entry of [3H]norepinephrine, [125I]albumin and Evans blue from blood into brain following unilateral osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 1978;145:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapoport SI, Fredericks WR, Ohno K, et al. Quantitative aspects of reversible osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:R421–431. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1980.238.5.R421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neuwelt EA, Barnett PA, Frenkel EP, et al. Chemotherapeutic agent permeability to normal brain and delivery to avian sarcoma virus-induced brain tumors in the rodent: observations on problems of drug delivery. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:154–160. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyle FM, Eller SL, Grossman SA, et al. Penetration of intra-arterially administered vincristine in experimental brain tumor. Neuro Oncol. 2004;6:300–305. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuwelt EA, Howieson J, Frenkel EP, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiagent chemotherapy with drug delivery enhancement by blood-brain barrier modification in glioblastoma. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:573–582. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198610000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyagami M, Tsubokawa T, Tazoe M, et al. Intra-arterial ACNU chemotherapy employing 20% mannitol osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption for malignant brain tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1990;30:582–590. doi: 10.2176/nmc.30.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hori T, Muraoka K, Saito Y, et al. Influence of modes of ACNU administration on tissue and blood drug concentration in malignant brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:372–378. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.3.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall WA, Doolittle ND, Daman M, et al. Osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption chemotherapy for diffuse pontine gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2006;77:279–284. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillaume DJ, Doolittle ND, Gahramanov S, et al. Intra-arterial chemotherapy with osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption for aggressive oligodendroglial tumors: results of a phase I study. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:48–58. doi: 10.1227/01.. discussion 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doolittle ND, Miner ME, Hall WA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a multicenter study using intraarterial chemotherapy in conjunction with osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier for the treatment of patients with malignant brain tumors. Cancer. 2000;88:637–647. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<637::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angelov L, Doolittle ND, Kraemer DF, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption and intra-arterial methotrexate-based therapy for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: a multi-institutional experience. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3503–3509. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remsen LG, Pagel MA, McCormick CI, et al. The influence of anesthetic choice, PaCO2, and other factors on osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption in rats with brain tumor xenografts. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:559–567. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199903000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuwelt EA, Specht HD, Howieson J, et al. Osmotic blood-brain barrier modification: clinical documentation by enhanced CT scanning and/or radionuclide brain scanning. Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:829–835. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greene HS. The transplantation of tumors to the brains of heterologous species. Cancer Res. 1951;11:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greene HS. The transplantation of human brain tumors to the brains of laboratory animals. Cancer Res. 1953;13:422–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pantelouris EM. Absence of thymus in a mouse mutant. Nature. 1968;217:370–371. doi: 10.1038/217370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ovejera AA, Houchens DP. Human tumor xenografts in athymic nude mice as a preclinical screen for anticancer agents. Semin Oncol. 1981;8:386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bullard DE, Schold SC, Jr., Bigner SH, et al. Growth and chemotherapeutic response in athymic mice of tumors arising from human glioma-derived cell lines. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981;40:410–427. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neuwelt EA, Frenkel EP, D’Agostino AN, et al. Growth of human lung tumor in the brain of the nude rat as a model to evaluate antitumor agent delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2827–2833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neuwelt EA, Pagel M, Barnett P, et al. Pharmacology and toxicity of intracarotid adriamycin administration following osmotic blood-brain barrier modification. Cancer Res. 1981;41:4466–4470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levin VA, Kabra PM, Freeman-Dove MA, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intracarotid artery 14C-BCNU in the squirrel monkey. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:587–593. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.4.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassenbusch SJ, Anderson JH, Colvin OM, et al. Predicted and actual BCNU concentrations in normal rabbit brain during intraarterial and intravenous infusions. J Neurooncol. 1996;30:7–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00177438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuster JM, Friedman HS, Archer GE, et al. Intraarterial therapy of human glioma xenografts in athymic rats using 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2338–2343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kurpad SN, Friedman HS, Archer GE, et al. Intraarterial administration of melphalan for treatment of intracranial human glioma xenografts in athymic rats. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3803–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remsen LG, McCormick CI, Sexton G, et al. Decreased delivery and acute toxicity of cranial irradiation and chemotherapy given with osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption in a rodent model: the issue of sequence. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:731–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Q, Gallo JM. Differential effect of sunitinib on the distribution of temozolomide in an orthotopic glioma model. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:301–310. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zink WE, Foley CP, Dyke JP, et al. Novel microcatheters for selective intra-arterial injection of fluid in the rat brain. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1190–1196. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dropcho EJ, Rosenfeld SS, Morawetz RB, et al. Preradiation intracarotid cisplatin treatment of newly diagnosed anaplastic gliomas. The CNS Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:452–458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roosen N, Kiwit JC, Lins E, et al. Adjuvant intraarterial chemotherapy with nimustine in the management of World Health Organization Grade IV gliomas of the brain. Experience at the Department of Neurosurgery of Dusseldorf University. Cancer. 1989;64:1984–1994. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891115)64:10<1984::aid-cncr2820641003>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vega F, Davila L, Chatellier G, et al. Treatment of malignant gliomas with surgery, intraarterial chemotherapy with ACNU and radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 1992;13:131–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00172762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shapiro WR, Green SB, Burger PC, et al. A randomized comparison of intra-arterial versus intravenous BCNU, with or without intravenous 5-fluorouracil, for newly diagnosed patients with malignant glioma. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:772–781. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.5.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Recht L, Fram RJ, Strauss G, et al. Preirradiation chemotherapy of supratentorial malignant primary brain tumors with intracarotid cis-platinum (CDDP) and i.v. BCNU. A phase II trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:125–131. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199004000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feun LG, Wallace S, Yung WK, et al. Phase-I trial of intracarotid BCNU and cisplatin in patients with malignant intracerebral tumors. Cancer Drug Deliv. 1984;1:239–245. doi: 10.1089/cdd.1984.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Safdari H, Mompeon B, Dubois JB, et al. Intraarterial 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea chemotherapy for the treatment of malignant gliomas of the brain: a preliminary report. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:490–497. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feun LG, Lee YY, Yung WK, et al. Phase II trial of intracarotid BCNU and cisplatin in primary malignant brain tumors. Cancer Drug Deliv. 1986;3:147–156. doi: 10.1089/cdd.1986.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Geier JM. Pathology of high-dose intraarterial BCNU. Surg Neurol. 1989;31:435–443. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(89)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tonn JC, Roosen K, Schachenmayr W, et al. Brain necroses after intraarterial chemotherapy and irradiation of malignant gliomas--a complication of both ACNU and BCNU. J Neurooncol. 1991;11:241–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00165532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Follezou JY, Fauchon F, Chiras J, et al. Intraarterial infusion of carboplatin in the treatment of malignant gliomas: a phase II study. Neoplasma. 1989;36:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clocchlatti L, Cartei G, Lavaroni A, et al. Intra-arterial chemotherapy with carboplatin (CBDCA) and vepesid (VP16) in primary malignant brain tumours. Preliminary findings. Interventional Neuroradiology. 1996;2:277–281. doi: 10.1177/159101999600200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Newton HB, Slivka MA, Stevens CL, et al. Intra-arterial carboplatin and intravenous etoposide for the treatment of recurrent and progressive non-GBM gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2002;56:79–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1014498225405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fortin D, Desjardins A, Benko A, et al. Enhanced chemotherapy delivery by intraarterial infusion and blood-brain barrier disruption in malignant brain tumors: the Sherbrooke experience. Cancer. 2005;103:2606–2615. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, 2nd, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–1972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brandsma D, van den Bent MJ. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the treatment of gliomas. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:633–638. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328332363e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarin H, Kanevsky AS, Wu H, et al. Physiologic upper limit of pore size in the blood-tumor barrier of malignant solid tumors. J Transl Med. 2009;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hofstetter C, Boockvar J. Generation of neural stem cells: a team approach. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:N22–23. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000390618.03950.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hofstetter C, Boockvar J. Tapping an abundant resource: engineering pluripotent stem cells from blood. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:N25 . doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000389740.23932.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fatoo A, Nanaszko MJ, Allen BB, et al. Understanding the role of tumor stem cells in glioblastoma multiforme: a review article. J Neurooncol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0406-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]