Abstract

Background

Active home-based treatment represents a new model of health care. Chronic treatment requires continuous access to facilities that provide cancer care, with considerable effort, particularly economic, on the part of patients and caregivers. Oral chemotherapy could be limited as a consequence of poor compliance and adherence, especially by elderly patients.

Methods

We selected 30 cancer patients referred to our department and treated with oral therapy (capecitabine, vinorelbine, imatinib, sunitinib, sorafenib, temozolomide, ibandronate). This pilot study of oral therapy in the patient’s home was undertaken by a doctor and two nurses with experience in clinical oncology. The instruments used were clinical diaries recording home visits, hospital visits, need for caregiver support, and a questionnaire specially developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), known as the QLQ-C30 version 2.0, concerning the acceptability of oral treatment from the patient’s perspective.

Results

This program decreased the need to access cancer facilities by 98.1%, promoted better quality of life for patients, as reflected in increased EORTC QLQ-C30 scores over time, allowing for greater adherence to oral treatment as a result of control of drug administration outside the hospital. This model has allowed treatment of patients with difficult access to care (elderly, disabled or otherwise needed caregivers) that in the project represent the majority (78% of these).

Conclusions

This model of active home care improves quality of life and adherence with oral therapy, reduces the need to visit the hospital, and consequently decreases the number of lost hours of work on the part of carers. Management of the service by the professionals involved revealed excellent control of the process by nursing staff, with minimal visits involving doctors.

Keywords: cancer, treatment, home-based, quality of life, compliance

Introduction

Tumor chronicity is a large and growing consideration as a result of successful treatment, the greater number of drugs available, and earlier diagnosis, which allow more effective therapeutic intervention. In recent years, with molecularly targeted drugs and a better understanding of the natural history of cancer, the treatment goal has changed: not always trying to destroy the neoplastic population. Often it can be inhibited, for a long time, blocking the biomolecular mechanisms that underlie the replication of cells, in order to control the spread of the local and systemic tumors that, maybe, determine a chronic clinical manifestation.

Oral therapy has assumed an important role in this new treatment strategy and, according to recent data, this role will expand in the near future. Assessment of the oncology pipeline in pharmaceutical companies shows that approximately 25% of more than 400 molecules currently in development are planned as oral formulations.1 The advent of these oral chemotherapeutic drugs has come about because of evidence showing that oral formulations are better accepted by patients with cancer, as highlighted in a study conducted 13 years ago in which patients were asked whether they preferred to be treated at home with 4–5 pills per day for 5 days per month or with intravenous chemotherapy in hospital.2 It is widely accepted, although not proven, that oral agents are more convenient for patients, have a less complex regimen, a better side effect profile, a wider therapeutic index, and represent significant cost savings to the health care system.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens have been designed to enable the maximum tolerated dose of chemotherapy to be given to optimize cell death using a single dose followed by a period of several weeks to allow recovery of the bone marrow. This episodic cyclic administration lends itself to injectable therapy. Oral chemotherapy is changing this pattern. Many current cancer therapies have a mainly cytostatic action and therefore are fully effective when administered chronically, as well as entering the peritumoral microenvironment which tumor cells are continually exposed to. This mechanism of action requires oral therapy to be given almost every day. In addition, a schedule of daily administration at the same time often does not cause the dose-limiting side effects seen with high-dose intermittent administration, making it unnecessary to include recycling schemes to allow recovery of bone. So now we have a turning point in innovative oral chemotherapy, ie, cyclic high-dose therapy administered intravenously by health professionals is no longer necessary, and can be replaced by a constant dose of oral self-administered therapy taken by the patient at home. Future prospects are leaning more and more towards a process of dehospitalized oncology, and the advent of oral chemotherapy will surely make an essential contribution in this direction, providing the basis for new models of care.

Knowledge of the natural history of the disease and development of standardized protocols for different lines of chemotherapy have allowed us to control the evolution of many types of cancer, increasing overall survival and the disease-free interval in the early stages, and the time to progression and remission in the advanced stages. For example, survival of patients with breast cancer has been greatly increased by introduction of adjuvant chemotherapy protocols in which different modalities can be combined to improve the outcome and quality of life for patients,3 and molecular targeted drugs like Herceptin® have profoundly changed the natural history of the disease.

The chronicity of many tumors also involves use of oral chemotherapy. For example, drugs such as imatinib have enabled long-term control and even recovery for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors.4 Other drugs used in the treatment of cancer, such as capecitabine and vinorelbine, have made an important contribution in the fight against breast, colon, and lung cancers.5 New targeted drugs such as lapatinib6 and erlotinib7 are widely used in the treatment of breast and lung cancers. The study of rarer cancers, such as hepatocellular or renal cell carcinomas, has led to the advent of oral agents such as sunitinib8 and sorafenib.9

Nowadays, people can live “longer and better” with malignancy. From 1971 to 2001, the number of cancer survivors in the US increased from 3.0 million to 9.8 million, with tumors of the breast, prostate, and colon or rectum being the most common types of malignancy among survivors and comprising 51% of diagnoses.10 This new epidemiological reality should prompt us towards more careful organization and better management of the patient. Today, the goals of cancer care, in addition to “curing” the patient, also involve ensuring better quality of life as part of more rational and efficient management of the disease in its different phases. For example, “living with cancer” and therefore control of symptoms, are the features and benefits of integrative medicine in the treatment of metastatic nonsmall cell carcinoma.11 Clinical benefit is an endpoint that is widely understood and accepted as part of clinical trials in oncology.

In patients with advanced cancer or metastatic spread, the curative possibilities are limited; however, with specific integrated multidisciplinary treatment, cancer can become a chronic disease, with the patient still enjoying a good quality of life. This paper reports on a pilot project known as Active Home Care that aims to bring oral chemotherapy into patients’ homes, and monitored treatment adherence, acceptance of treatment by patients, quality of life, satisfaction with health care, and potential cost reduction.

Materials and methods

Active Home Care is a project enabling home-based care for patients who can be actively maintained with oral anticancer drugs, thus transferring their treatment from the hospital to the home. Between December 2009 and December 2010 we selected 30 cancer patients referred to our department for participation in this pilot initiative. Their treatment consisted of anticancer drugs used most often in oral formulations (capecitabine, vinorelbine, imatinib, sunitinib, sorafenib, temozolomide, ibandronate). One oncologist and two nurses saw the patients at home, periodically checking their adherence to treatment, quality of life, and satisfaction with health care, as well as managing any related toxicities.

Thirty patients (13 males and 17 females) of mean age 71 (range 33–83) years were enrolled over a period of 12 months; 73% of them were over 70 years of age. A range of cancers were included, including breast cancer (9/30, 30%), colon cancer (9/30, 30%), lung cancer (6/30, 20%), renal cell carcinoma (2/30, 6.6%), astrocytoma (2/30, 6.6%), gastrointestinal stromal tumor (1/30, 3.3%), Kaposi’s sarcoma (1/30, 3.3%), and endometrial carcinoma (1/30, 3.3%). One patient had breast and colon cancer. A trained nurse delivered the home-based chemotherapy. Decisions to modify the dose were made by the medical oncologist at monthly visits to review toxicity during the previous cycle. A protocol allowing for a telephone call to an oncologist was established in order to manage any potential acute adverse effects during delivery of chemotherapy at home. The nurse contacted the patients more frequently than the doctor to confirm adherence to treatment and to report any toxicity.

We measured and recorded treatment toxicity every four weeks using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group classification.12 Grade 3 or 4 toxicity resulted in withdrawal from the study. We measured adherence to oral treatment through the effective control of administration, taken from the clinical diaries of patients and direct observation by operators. We classified reasons for withdrawing from the trial as: unacceptable toxicity of chemotherapy; disease progression; or voluntary withdrawal not related to either side effects or disease progression. Only the latter category was considered to reflect lack of compliance. We asked the patients about any unplanned use of primary care, emergency departments, or hospitalization. We included any use of health services not covered in the protocol, including visits to the emergency department, outpatient clinics, admission to hospital, or primary care centers. We considered all primary care visits to be unscheduled, even when they were related to comorbid conditions. We measured patient quality of life using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire.13 This includes several functional scales (physical, emotional, cognitive, social), a global health status quality of life scale, and single measures of symptom severity (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties). We also measured quality of life using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale.14

Adherence to oral chemotherapy and its administration at home was measured also by periodic administration of a questionnaire designed to identify the degree of satisfaction with oral chemotherapy. This included several items that measured general satisfaction with health care received, availability of doctors and nurses, continuity of care, personal qualities of nurses (related to perceived interest in the patient), and communication with doctors and nurses. Quality of life and satisfaction questionnaires were administered at the start of the trial, every three months thereafter, and at the end of treatment. We also analyzed by the weight of litigation prevented the development of this type of assistance according the relationship between patients and caregivers. Recordings were made of approximate savings in terms of direct costs related to health expenditure and of indirect costs, calculated by reference to the number of hours/days to avoid patient and his family members, access to health facilities. Ninety percent of the patients enrolled needed to be accompanied by a relative to hospital, which occurred at least three-monthly on an outpatient basis, not including possible emergencies and hospitalizations.

Results

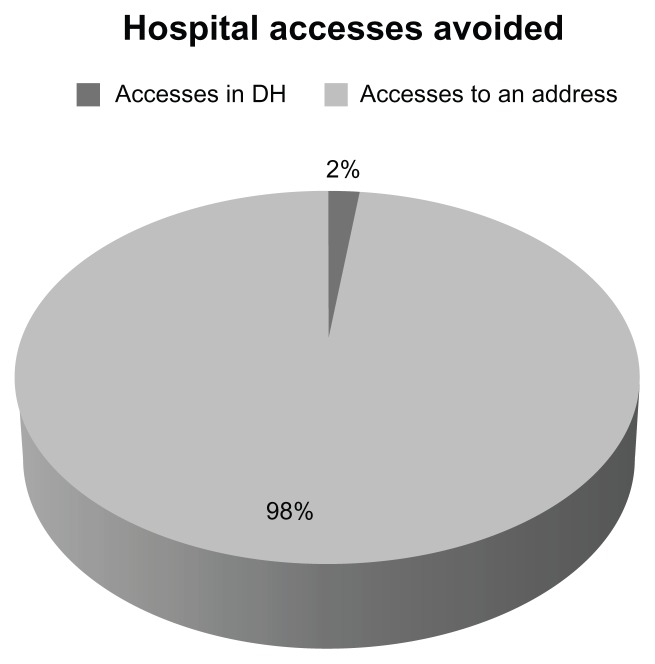

During the course of one year, 321 home visits were made. Oral treatment was fully accepted and complied with by all patients. All patients were in agreement with and reported being satisfied with the prospect of the Active Home Care program. There were no cases of voluntary cessation of chemotherapy, and all patients completed their planned treatment. Patients with Grade 3 or 4 toxicity received either an adequate drug dose or underwent a delay in treatment, but none stopped treatment. Only six visits were made to the hospital oncology unit on an emergency basis, which translated into 98% of hospital visits being avoided (Figure 1). These results are interesting considering the majority of patients enrolled (78%) had difficulties in access to care due to age, disability or reliance on caregivers.

Figure 1.

Hospital visits avoided.

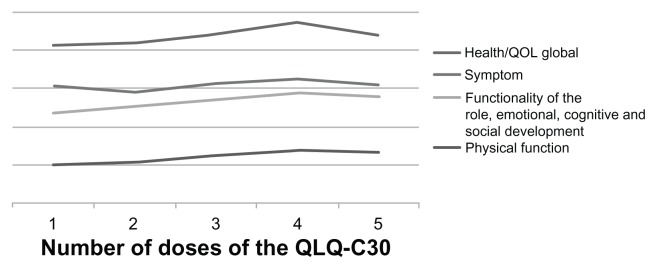

This project has promoted the quality of life of patients receiving oral chemotherapy, as indicated by an increase in EORTC QLQ-C30 scores over time, allowing for greater adherence to oral treatment, because of control of self-administration outside the hospital. Insomnia was the commonest symptom, followed by fatigue, pain, and appetite loss. Role functioning improved after treatment. Scores on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale and global health status remained stable. Quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30 version 2.0) scores showed improvement in symptoms, especially at the beginning of the study, and better perception of health and global quality of life over time (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Score responses to the questionnaire European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 version 2.0

| Physical function | Functionality of role, emotional, cognitive and social development | Symptoms | Health/QOL global | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First administration (n = 30) | Average 49.7; min 0; max 100 | Average 68.7; min 13.3; max 100 | Average 34.3; min 5.1; max 82.05 | Average 53.8; min 0; max 100 |

| Second administration (n = 20) | Average 53.3; min 0; max 100 | Average 73.3; min 46.6; max 100 | Average 18.8; min 5.1; max 33.3 | Average 64.15; min 41.6; max 100 |

| Third administration (n = 15) | Average 63.3; min 20; max 100 | Average 71.6; min 20; max 90 | Average 21.7; min 5.1; max 53.8 | Average 64.5; min 25; max 100 |

| Fourth administration (n = 11) | Average 68.3; min 30; max 100 | Average 74.6; min 30; max 90 | Average 18.7; min 5.1; max 53.8 | Average 74.5; min 35; max 100 |

| Fifth administration (n = 7) | Average 65.3; min 25; max 100 | Average 73.6; min 30; max 100 | Average 15.7; min 5.1; max 43.8 | Average 64.5; min 25; max 100 |

Abbreviations: max, maximum; min, minimum; QOL, quality of life.

Figure 2.

Variability in quality of life over time.

Patient satisfaction, assessed after completion of treatment, showed a significant difference in the perception of nurse availability, and communication with nurses and the personal qualities of nurses were rated more highly at the end of treatment. All patients willingly accepted the initiative and established positive relationships with their attending health professionals, which was very helpful for the success of treatment and reflected the prominent role of nurses, who became the backbone of assistance for patients being treated at home. Ready access to nursing staff trained in the management of cancer patients and minimum involvement of medical staff avoided any patient-doctor conflict. Finally, the Active Home Care initiative, which minimizes the need for hospital visits, resulted in savings for both the patient and their family in terms of working hours lost and travel expenses. The carers were mostly people of working age (78%), who had to take hours/days off work and absorb the costs of travel, often waiting in the hospital for several hours, not to mention the stressful emotional burden that the patient and their families are subjected to. Implementation of this project, taking into account the number of home visits made and the number of hospital visits avoided, has translated into cost savings to the public purse, especially for the management of side effects, such as diarrhea and constipation, which could be managed at home with the help of health professionals. Finally, no episodes of patient-doctor conflict were reported.

Discussion

Access and adherence to care is crucial for successful treatment of a chronic indolent neoplastic disease. The prospect of cure need not be related to “distance”. A large proportion of patients live more than 150 km away from their nearest oncology service, and it is important to identify a support network for planning and improvement of service delivery, because geographic access is often a significant problem in terms of the outcome of treatment.15 The cancer patient, particularly if elderly, is subjected to stress during their treatment that is not only physically taxing, but also burdensome to the psyche: multiple courses of intravenous therapy requires frequent hospital visits and enormous distress for patients and their families. Families are often forced to make many sacrifices in terms of economic resources to meet the cost of transport and permanent stays in cancer centers. Compliance, often called adherence, can be defined as the extent to which a patient’s behavior regarding treatment is consistent with that prescribed.16 Adherence to any treatment for long periods is largely determined by the perception of individual risks, benefits, and costs of intervention.17 Adherence to treatment is a complex and multifaceted issue, and is able to modify the results of therapy in a substantial way.18

There are instruments available to health professionals in oncology for measuring the degree of adherence and for making it high enough to enable a close relationship between the health professional and patient in terms of accurate information regarding the course of treatment, its benefits, and potential toxicity. Patient education by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health care providers can be very useful. For example, programs have been developed to increase the likelihood of adherence using patient education, counseling, and training in a controlled environment. Lee et al undertook a multiphase, prospective, controlled, randomized trial at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, which showed that an intensive multidimensional strategy comprising individualized education on the treatment of blisters and follow-up with a pharmacist every two months improved adherence with medication in elderly patients taking at least four concomitant agents on a long-term basis.19

Accessing treatment becomes more difficult with advancing age, and a large number of elderly patients present with very advanced disease at diagnosis and curative treatment is then not an option. The treatment strategy should be decided upon taking into account the likely life expectancy of the patient; women aged 65 years have a mean life expectancy of 21 years and men of the same age have a mean life expectancy of 18 years, while a healthy man or woman aged 75 years has a likely life expectancy of 10–13 years. Advancing age not only increases the risk of developing cancer but also increases the likelihood of comorbidities, and underlying conditions and/or disabilities often make it difficult for patients to complete a treatment program. The need to take more drugs to treat comorbidities, the infrequent availability of adequate home support, and the need for long-term therapy are all factors which contribute to noncompletion of treatment.

The last decade has seen accelerated development of oral anticancer drugs, especially of cytotoxic agents that interact with surface receptors of tumor cells and other molecules involved in regulation of proliferating tumor cells, ie, so-called biologics or targeted therapy. The number of antineoplastic drugs administered orally is likely to continue growing. It is estimated that the percentage of oral anticancer drugs will increase to 25% by 2013, compared with 10% in 2008, and that 85% of these will be targeted therapies.20 The advent of oral chemotherapy drugs reflects the fact that the oral route is preferred by patients with cancer, as highlighted in a study conducted 13 years ago in which patients were asked whether they preferred to be treated at home with 4–5 pills per day for 5 days per month or with intravenous chemotherapy in the hospital.21 It is widely believed, although not proven, that oral agents are more convenient for patients, reduce the complexity of the regimen, have a better safety profile, show a wider therapeutic index, and are cost-effective in terms of health care expenditure. Research has focused on developing oral formulations of cytotoxic chemotherapy previously only administered intravenously, eg, cisplatin, docetaxel, and topotecan. Experts suggest that markets will exist for both oral and intravenous administration of several antineoplastic drugs. Future prospects for dehospitalization of oncology and the advent of oral chemotherapy will surely make an essential contribution in this direction, providing the basis for new models of care.

New therapeutic possibilities offered by the advent of oral chemotherapy in oncology, self-administered by the patient at home, have led to the emergence of new needs assistance. Self-administration of oral chemotherapy would be convenient because cancer patients can receive care at home rather than in the supervised and controlled setting of a hospital. This new paradigm shifts the focus of care to the patient who becomes leasing of therapy and not only the recipient while healthcare professionals play an important role in overseeing the care pathway.22 This creates a need for health care professionals to monitor adherence with this new route of administration with regard to optimal therapeutic success and for patients to deal with issues related to accessing cancer treatment facilities, including involvement of family members, lost working hours, transport of the debilitated elderly, and use of healthcare resources. Oral treatments are suitable for home-based therapy because most patients take pills in the home and manage their treatment directly or with the help of familiar caregivers.23,24 An Irish report demonstrated that home care cut costs by two-thirds compared with hospital care.25 In a large study carried out in the US, 756 patients with advanced disease were included in a patient-centered model, including home visits and telephone calls, which resulted in a smaller number of hospital admissions (38%), emergency room visits (30%), and confirmed side effects, including nausea, anemia, and dehydration.26

Our study confirms that this active home-based approach has many advantages, including fewer hospital admissions, with lower economic costs and hospital congestion, a better doctor-patient-family relationship, improved quality of life and removal of barriers to accessing of care. The experience of the Active Home Care project may be a good starting point for the building of a health care system that guarantees cancer sufferers an efficient and innovative service that takes into account patients’ actual needs, especially those experiencing barriers to accessing care.

Conclusion

The advent of oral chemotherapy represents a real benefit for patients, especially in terms of quality of life, and has paved the way for new types of assistance for cancer patients. Home-based cancer treatment represent a new model of care that can include active assistance of patients treated with oral, subcutaneous, and even intravenous agents (chemotherapy or biologics).27 Implementation of the Active Home Care project has resulted in a noticeable improvement in quality of life of patients treated with home-based oral chemotherapy, allowing continuation of the treatment program to be fully accepted and shared by both patients and the family members who care for them. The project has significantly reduced the number of hospital visits made by patients and their carers, resulting in a reduction of both direct and indirect costs, thus improving the cost-effectiveness of public spending.25,26 It can be concluded that this project is a starting point for a much broader discussion concerning the home-based cancer care model in which nurses have the central role. Our experience is that nursing assistance is a fundamental aspect of high-quality home-based chemotherapy. However, it must be stressed that this was a pilot study and that more experience is needed to be able to assess the real advantage of oral home-based treatment for patients with cancer.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the Avola City Council for its support of the Active Home Care project.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Palmieri FM, Barton DL. Challenges of oral medications in patients with advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(4 Suppl 2):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, et al. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:110–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsoutsou PG, Belkacemi Y, Gligorov J, et al. Optimal sequence of implied modalities in the adjuvant setting of breast cancer treatment: an update on issues to consider. Oncologist. 2010;15:1169–1178. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welt A, von Minckwitz G, Oberhoff C, et al. Phase I/II study of capecitabine and vinorelbine in pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:64–69. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cancer survivors – United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue D, Li PP. Clinical benefits as endpoints in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with integrative medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17:228–231. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. Neoplasma. 1980;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira EX, Melo EC, Pinheiro RS, et al. Access to cancer care: mapping hospital admissions and high-complexity outpatient care flows. The case of breast cancer. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:317–326. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000200013. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Compliance In Health Care. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Love RR, Cameron L, Connell BL, Leventhal H. Symptoms associated with tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1842–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tebbi CK. Treatment compliance in childhood and adolescence. Cancer. 1993;71(Suppl 10):3441–3449. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10+<3441::aid-cncr2820711751>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calleja Patricia, Huarte Judit, Agüeros Maite, Ruiz-Gatón Luisa, Espuelas Socorro, Irache Juan M. Molecular buckets: cyclodextrins for oral cancer therapy. Therapeutic Delivery. 2012;3(1):43–57. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, et al. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:110–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedell CH. A changing paradigm for cancer treatment: the advent of new oral chemotherapy agents. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7(Suppl 6):5–9. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.S6.5-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:56–66. doi: 10.3322/caac.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(Suppl 3):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall M, Lloyd H. Evaluating patients’ experience of home and hospital chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2008;7:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweeney L, Halpert A, Waranoff J. Patient-centered management of complex patients can reduce costs without shortening life. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tralongo P, Ferraù F, Borsellino N, et al. Cancer patient-centered home care: a new model for health care in oncology. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:387–392. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S22119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]