Abstract

Standardized patients have been utilized for nearly 40 years in teaching medical curricula. Since the introduction of this teaching methodology in the early 1960s, the use of standardized patients has steadily gained acceptance and is now incorporated into medical education across the country. This “standardization” was useful for teaching and evaluating medical students and residents. However, as this modality expanded beyond medical schools to include seasoned physicians, the limitations of “one-size-fits-all” clinical scenarios became apparent. In teaching clinician-patient communication (CPC) courses to practicing physicians, we have discovered that flexibility and improvisation on the part of the actor enhances the educational experience. The term “care actor” more accurately describes this role than standardized patient. The care actors in our CPC courses have become integral contributors to the education process, serving not only as simulated patients but also as coaches and collaborators. This article outlines the history of standardized patients in medical education and presents a three-part framework for effectively using care actors to teach clinician-patient communication: setting the stage, skill practice, and providing feedback.

Introduction

Standardized patients have been used effectively to teach communication and physical examination skills to medical students, residents, and practicing physicians for nearly four decades. This modality has become one of the most pervasive and highly touted of the newer teaching methodologies in medical education.1 Originally, patients presented their own medical problems. Eventually, actors were trained to simulate problems with a pre-defined set of historical, emotional, and physical criteria. Usually, these encounters would occur within the confines of a structured teaching or evaluation process.2–4

Although a scripted and standardized patient scenario often worked well for students or residents early in their training, more experienced physicians seemed to learn better in situations that allowed increased flexibility and customization. The advancement of the role of the standardized patient to that of a “care actor” for teaching clinician-patient communication skills has been a marked improvement. The care actor takes on a more active and collaborative teaching role. The physician presents the care actor with a realistic clinical scenario based on a clearly stated communication goal. The physician and coach also set the level of emotion and affect for the care actor (eg, “really angry,” “slightly scared,” “moderately frustrated,” “somewhat withdrawn”). The care actor then portrays the case in a manner geared toward the stated learning objective.

The Standardized Patient

Howard S Barrows first began to use “programmed patients” while teaching third-year neurology clerks at the University of Southern California (USC) in 1963 and published his early experiences a year later.5 Although today he is often referred to as the “father” of the standardized patient, Barrows was, at the time, maligned by some medical educators, who were skeptical of the practice. After learning of Barrows' innovation, the LA Herald-Examiner ran a headline exclaiming that “Hollywood Invades USC Medical School,” and the San Francisco Chronicle reported that scantily clad models were “making life a little more interesting for the USC medical students.”1 These reports made widespread acceptance of this teaching methodology all the more difficult in the beginning.

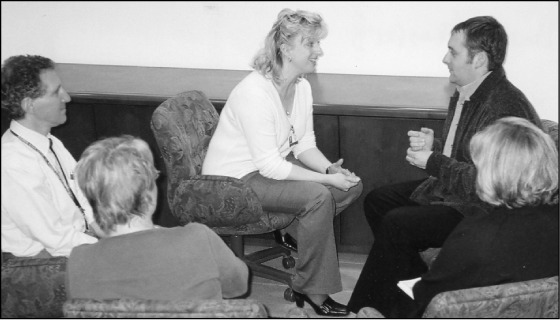

Family physician Victoria Smith, MD (center) practices a medical interviewing technique with care actor Drew Frady (right) during a recent Physician-Patient Interaction course while coaches Jeffrey Morse, MD; Jan Waterman; and Nancy Ashworth (left to right) observe.

By definition, a standardized patient faithfully reproduces a scripted clinical scenario, often with predetermined learning objectives in mind. The objective is to have the actor play the role with as little variability as possible. Standardized patients are particularly useful in teaching medical students, who lack clinical experience to formulate realistic scenarios on their own. With standardized patients, an instructor scripts the “case” in advance with learning objectives in mind. A weakness of this modality is that the standardized patient may have a hidden agenda that can thwart the physician/learner's primary focus.

Standardized patients have been incorporated successfully in many medical schools, including the University of Colorado and the University of Hawaii.6–8 Studies have shown a high level of acceptance and have concluded that they are helpful for instruction.9–10 Medical students and residents, as well as practicing physicians, reportedly have difficulty differentiating between standardized and “real” patients.11 Our own experience mirrors those of other institutes in that the use of the standardized patient is popular and effective.

The Care Actor

In recent communication skills courses incorporating the Four Habits model,12 it has been useful to collaborate with actors to focus on physicians' self-determined learning goals. This methodology, adopted in part from the “Communication Skills Intensive” program co-developed by Terry Stein, MD, of The Permanente Medical Group in Northern California and the Bayer Institute for Healthcare Communication, has proved highly effective. The skill practice sessions are learner-focused: The physician chooses a communication skill to practice and then creates a relevant clinical scenario in partnership with a coach and a care actor. The care actor is given direction by the physician regarding the clinical setting, presentation, emotion, affect, and degree of difficulty. Because there are clearly identified goals and objectives in mind, a successful practice session can be readily achieved. In addition, the opportunity exists for the coach or learner to “stop, rewind, and try again” if desired.

Pitfalls

In our experience, the use of care actors has been overwhelmingly positive. Surveys completed by physicians attending our courses have uniformly praised the skills and teaching ability of our care actors. However, there are potential downsides to this methodology: First, there are no randomized, controlled trials proving the effectiveness of standardized patients in teaching clinical or communication skills. Although CPC appears to improve, there is no scientific proof per se. Second, the success of this methodology depends, in part, on the commitment and skill level of the actors. We are fortunate to have a highly dedicated group of actors who meet with us regularly to discuss and clarify their roles and to enhance their coaching and feedback skills. Our care actors spend many hours in specialized training and practice in portraying various disease states and in improvising clinical scenarios. Finally, actors' salaries are not insignificant. Although we budget accordingly, the financial commitment should not be overlooked.

A Model For Skill Practice

We have found that a three-stage model facilitates teaching of CPC with care actors: setting the stage, skill practice, and providing feedback. This model increases the success of the learning session and reduces unhelpful and distracting variability.

I. Setting the Stage

Thoughtful planning in the beginning can reduce later problems. The key to a successful communication skill practice session is proper setup. Setting the stage includes the following:

Assure confidentiality and trust.

Assist the physician/learner in selecting a communication skill he or she wishes to practice; for example, planning the visit or demonstrating empathy.12

Assist the physician/learner and care actor in developing a case relevant to the physician's specialty. The scenario should be straightforward and not an exact reconstruction of “the worst case imaginable!” It is important to remember that the practice session should focus on a small portion of a clinical interview, not an entire history and physical examination.

Check to see that the care actor understands the clinical scenario as well as the emotion, affect, and communication goal.

Check with the physician/learner about “ground rules” including stopping the session when the goal has been achieved, permission to interrupt/redirect, and willingness to “stop, rewind, and try again.”

It is also useful to assign other group participants specific observation tasks. For example, one observer might watch for body language and nonverbal communication. Another observer might write the first five words of each sentence the practicing physician says, thus allowing him/her to identify repetitive words (ie, “uh-huh,” “okay”) or closed-ended sentences.

II. Skill Practice

The coach restates the communication goal at the beginning of the practice session for clarity (eg, “Bill, you said you'd like to try a statement of empathy with this angry patient that you've outlined for us. Specifically, you want to identify and acknowledge the patient's emotion, pause briefly, and then proceed with the interview. At that point, we'll know that you've been successful. Okay? Let's begin …”). The scenario begins with the care actor portraying the role and the physician embarking on the interview. It is in the nature of many clinicians to start down the “biomedical pathway.” If the physician starts asking a series of closed-ended or biomedical questions, (eg, “Have you had a fever?” or “Is the pain throbbing or stabbing?”), it may be worthwhile to interrupt and to redirect back to the stated communication goal. Once that goal is achieved, the session may be ended.

III. Providing Feedback

The practicing physician self-evaluates first. The communication goal should frame this. (“So, Bill, recalling that your goal was to try a statement of empathy with this patient, how do you think it went?”) Then the care actor gives feedback also framed in terms of the goal. (“Mrs Smith, how did it feel when Dr Jones used empathy to demonstrate understanding and concern?”) The care actor will then provide feedback from the patient's perspective. After surveying the group for specific feedback, the coach summarizes and provides his/her own comments.

Conclusion

In teaching CPC to practicing physicians, the more-flexible care actor concept is preferable to the less-flexible standardized patient. Given the experience of most physicians, as well as their diverse specialties, learning and enhancing communication skills seems to work best when they are allowed to customize the scenario to create relevant learning situations. Care actors, trained in improvisation, facilitate the exercise by portraying patients similar to those seen routinely by these physicians. Focusing on setting the stage, the practice session, and providing feedback helps assure a successful educational experience.

Standardized Patient.

Actor portrays a standard and scripted role

Preplanned with little variation

Case usually written by instructor ahead of time

Education objectives are instructor-generated: “I want you to learn …”

Good for students and early learners with little practical experience

Useful for evaluation and testing purposes

Case scenario may involve “hidden agenda” to uncover

Care Actor

Flexibility and improvisation on part of the actor

Actor partners with learner to create a realistic and relevant scenario

Increased learner input into the exercise (creating the case, choosing communication goal)

Education objectives are physician/learner generated: “I'd like to try …”

Actor has collaborative role in facilitation, feedback, and education

Flexibility and customization good for seasoned physicians of varied specialties

Transparent case scenario with no hidden agendas

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following for their creativity and input:

Terry Stein, MD, Director, Clinician-Patient Communication, TPMG Physician Education & Development; Glenna Kelly, Community Programs Manager, Educational Theater Programs, KP Colorado; Sue Niedringhaus, Special Projects Coordinator, Educational Theater Programs, KP Colorado; Becky Toma, Production Manager/Technical Director, Educational Theater Program, KP Colorado; and Renee S Harper, Training and Meeting Assistant, CPMG

References

- Wallace P. Following the threads of an innovation: the history of standardized patients in medical education. Caduceus. 1997 Autumn;13(2):5–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MA, Rogers LP, Markus JF, Dorsey NK, Blackwell TA, Petrusa ER. Standardized patient encounters. A method for teaching and evaluation. JAMA. 1991 Sep 11;266(10):1390–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.10.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows HS. An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. AAMC Acad Med. 1993 Jun;68(6):443–51. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199306000-00002. discussion 451–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colliver JA, Swartz MH. Assessing clinical performance with standardized patients. JAMA. 1997 Sep 3;278:790–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.9.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows HS, Abrahamson S. The programmed patient: a technique for appraising student performance in clinical neurology. J Med Educ. 1964 Aug;39:802–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi MH. Role of standardized patients in medical education. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Dec;60(12):323–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons KB, Palmer TJ, Bedinghaus JM, Cohan ME, Torre D. The role and future of standardized patients in the MCW curriculum. WJM. 2003;102(2):43–5. 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu NV, Barrows HS, Marcy ML, Verhulst SJ, Colliver JA, Travis T. Six years of comprehensive, clinical, performance-based assessment using standardized patients at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 1992 Jan;67(1):42–50. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batenburg V, Gerritsma JG. Medical interviewing: initial student problems. Med Educ. 1983 Jul;17(4):235–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenkron JC, Greenland P, Bowley N. Using patient instructors to teach behavioral counseling skills. J Med Educ. 1987 Aug;62(8):665–72. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole AD, Sanson-Fisher RW. Long-term effects of empathy training on the interview skills of medical students. Patient Couns Health Educ 1980 3d Quart. 2(3):125–7. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(80)80053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: The Four Habits model. Perm J. 1999 Fall;3(3):79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]