Abstract

This study explored the K. A. Dodge (1986) model of social information processing as a mediator of the association between interparental relationship conflict and subsequent offspring romantic relationship conflict in young adulthood. The authors tested 4 social information processing stages (encoding, hostile attributions, generation of aggressive responses, and positive evaluation of aggressive responses) in separate models to explore their independent effects as potential mediators. There was no evidence of mediation for encoding and attributions. However, there was evidence of significant mediation for both the response generation and response evaluation stages of the model. Results suggest that the ability of offspring to generate varied social responses and effectively evaluate the potential outcome of their responses at least partially mediates the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict.

Keywords: social information processing, relationship conflict, aggression, intergenerational transmission, adolescence

Aggressive conflict in intimate relationships takes the form of insults, verbal threats, and psychological control, as well as physical aggression, ranging from mild to life threatening. Physically and verbally aggressive marital conflict is associated with negative outcomes for both the partners involved and their children. Children who witness parents’ aggressive conflict display anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and substance abuse (Buehler et al., 1997; Fergusson & Horwood, 1998; Fincham, 1994; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003).

Of special interest is the well-replicated association between interparental conflict and subsequent conflicts of children with their own intimate partners (Buehler et al., 1997; Delsol & Margolin, 2004). Such findings have primarily concerned outcomes in men (Holtzworth-Munroe, Bates, Smutzler, & Sandin, 1997), but they also hold for women (Amato & Booth, 2001; Ehrensaft et al., 2003), although perhaps to a smaller degree (Stith et al., 2000). A few studies have suggested that children need not directly witness parental aggression to suffer negative effects; merely living in a house where aggressive parental conflict occurs puts a child at greater risk for being involved in an aggressive relationship later in life (Delsol & Margolin, 2004; Jouriles et al., 1998; Stith et al., 2000). Through what developmental process does aggressive conflict between parents come to be associated with relationship conflict of their children in early adulthood?

Social cognition is a likely mechanism in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. Researchers have proposed that living with maritally aggressive parents predisposes children to perpetrate or be the victim of later intimate partner conflict via the development of aggressive social–cognitive processing patterns (Brendgen, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Wanner, 2002; Lichter & McCloskey, 2004; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001). Among the supporting evidence, dating violence perpetration has been associated with positive attitudes toward violence (Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001), and parental violence has been associated with offspring attitudes toward dating violence (Lichter & McCloskey, 2004) and beliefs that aggression increases self-esteem (Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, & Bowden, 1995).

Social information processing (SIP) is a promising type of social–cognitive model for those exploring the intergenerational link in relationship aggression. One particularly influential SIP model is that of Dodge and colleagues (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge, 1986). The Dodge (1986) SIP model proposes four cognitive steps. The first step, encoding, concerns how much attention the child allocates to the many external and internal cues present in a given social situation. The second step, interpretation, is focused on the child’s attributions of intent. The third step is response search, or response generation, which refers to the possible responses the child can imagine. In the fourth step, response evaluation, the child evaluates each possible response based on goals, expected results, and feelings of self-efficacy. The result of these processing steps is the enactment of a behavioral response or a nonresponse. Over 100 studies have found SIP measures to be significantly associated with child and adolescent aggressive behavior in general (Dodge, 2003), and the SIP constructs of intent attributions and response generation measured in adulthood have been found to be associated with men’s perpetration of domestic violence (Holtzworth-Munroe, 2000). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet explored the SIP association with parental and adolescent romantic relationship behavior.

Some research on the intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression has investigated constructs that can be related to SIP steps. O’Brien and Chin (1998) found stronger memory biases toward aggressive words in a word-recognition task for children who had been exposed to high levels of interparental conflict compared with children who had not been exposed to such conflict. This finding may be reflective of differences in encoding (SIP Step 1). Delsol and Margolin (2004) suggested that children who witness interparental violence may come to view violence as a legitimate response and may learn a less varied set of possible response options; conceptually, this pattern resembles the SIP steps of response evaluation and response generation. As mentioned, research has also focused on attitudes toward conflict and aggression (Lichter & McCloskey, 2004; Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001; Spaccarelli et al., 1995), which are somewhat similar to the response evaluation step in the SIP model. Thus, there is some evidence to suggest the value of exploring SIP as an explanatory mechanism in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. However, previous work has relied upon retrospective reports. Such reports contain data from a single reporter (usually a man), have explored only one cognitive processing construct at a time, and have not directly tested mediation (e.g., Lichter & McCloskey, 2004; O’Brien & Chin, 1998; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001). Research in which multiple stages of the social cognitive process and prospective measures of development in both genders are considered is needed.

The Present Study

Using prospective longitudinal data and multiple reporters, we asked whether SIP mediated the association between interparental aggression and offspring romantic relationship aggression. When their child was 5 years old, parents reported on their own and their partner’s relationship conflict, both at that time and since the child’s birth. We assessed their children’s SIP patterns in early and mid-adolescence by measuring the encoding, attributions, response generation, and response evaluation stages of the Dodge (1986) SIP model. Beginning at age 18, offspring reported on their own and their partner’s romantic relationship aggression. On the basis of previous reviews (Delsol & Margolin, 2004; Stith et al., 2000), we predicted a modest correlation between interparental conflict and offspring romantic relationship conflict. We also predicted significant mediation of the association between interparental conflict and offspring romantic relationship conflict in young adulthood by SIP. We did not expect our results to differ by gender, because women and men appear to use similar styles of verbal interaction and report similar levels of physical aggression within the confines of a romantic relationship (Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2004; Sorenson, Upchurch, & Shen, 1996), but we did explore gender effects for the sake of completeness. We also explored possible differences between perpetration and victimization.

Method

Participants

Participants and their parents were part of the longitudinal Child Development Project (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997). Families from Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee, and Bloomington, Indiana, were recruited as their children (N = 585) were entering kindergarten. Only 1 child from each family was included in the research. Of the original sample, 81% was European American, 17% was African American, and 2% was “other.” Hollingshead (1979) socioeconomic status was calculated in Year 1 of the study and was based on parental educational level and occupation. Hollingshead socioeconomic scores for the complete sample ranged from 8 to 66, with a mean of 39.5 (SD = 14.0). Institutional review boards at each participating university approved all measures and procedures. Informed consent was obtained from parents, and assent was obtained from minors at each data collection. When offspring reached age 18, they gave informed consent at the beginning of each data collection.

Measures

Interparental conflict

The Year 1 (child age 5) interview included items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). Mothers and fathers were interviewed separately and were asked how often they had engaged in 11 specific behaviors toward their spouse (see Appendix) and how often their spouse had engaged in these behaviors toward them. Parents reported how often they had experienced each behavior (a) in the past year (child age 4–5), and (b) in the 4 years prior (child age 0–4). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 1 = less than once a month, 2 = about once a month, 3 = more than once a month). We created four conflict subscales by combining frequency scores for each reporter and for each time period. These four subscales served as indicators of a latent parent conflict variable in the analyses. To account for missing data on individual items, we calculated each scale score as the average of all individual items (highest possible raw score = 3.0). Although the percentage of parents reporting no conflict for a particular time period was low (5%–8%), these scales were log transformed due to positive skew (highest possible transformed score = 1.39; see Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations Between Variables

| Variable | M | SD | n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother report, child age 0-4 | .46 | .30 | 410 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Mother report, child age 4-5 | .38 | .25 | 394 | .73** | — | |||||||||||||

| 3. Father report, child age 0-4 | .39 | .25 | 307 | .48** | .52** | — | ||||||||||||

| 4. Father report, child age 4-5 | .35 | .23 | 315 | .46** | .51** | .89** | — | |||||||||||

| 5. Encoding, age 13 | 1.51 | .42 | 337 | .07 | .05 | .05 | .05 | — | ||||||||||

| 6. Hostile attributions, age 13 | 5.19 | 1.76 | 375 | .00 | −.04 | .03 | −.04 | .03 | — | |||||||||

| 7. Response generation, age 13 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 375 | .11* | .05 | .02 | −.01 | .07 | .08 | — | ||||||||

| 8. Response evaluation, age 13 | .01 | .78 | 337 | .02 | .01 | .06 | .03 | .09 | .12* | .26** | — | |||||||

| 9. Hostile attributions, age 16 | 2.35 | .49 | 349 | .01 | .05 | .12 | .07 | .10 | .10 | .14* | .17** | — | ||||||

| 10. Response generation, age 16 | .07 | .14 | 349 | .22** | .17** | .08 | .05 | .08 | .12* | .17** | .22** | .37** | — | |||||

| 11. Response evaluation, age 16 | 1.99 | .40 | 349 | .12* | .14* | .08 | .05 | .14* | .14* | .15** | .42** | .50** | .61** | — | ||||

| 12. Relationship conflict, age 18 | .45 | .57 | 237 | .15* | .06 | .04 | .04 | −.08 | .05 | .26** | 22** | .17* | .10 | .18** | — | |||

| 13. Relationship conflict, age 19 | .48 | .39 | 237 | .17* | .15* | .11 | .10 | .01 | .15* | .13 | .19** | .18* | .23** | .25** | .37** | — | ||

| 14. Relationship conflict, age 20 | .50 | .35 | 254 | .11 | .08 | .06 | .06 | .00 | .15* | .07 | .25** | .21** | .29** | .26** | .34** | .49** | — | |

| 15. Relationship conflict, age 21 | .46 | .36 | 262 | .07 | .10 | .07 | .07 | .07 | .05 | .11 | .10 | .14* | .26** | .24** | .24** | .40** | .47** | — |

Note. Parental conflict measures, variables 1-4; social information processing measures, variables 5-11; offspring relationship conflict measures, variables 12-15. Missingness in offspring relationship conflict measures is high, because, at any given point, many participants were not in a dating relationship.

p < .05 (two-tailed).

p < .01 (two-tailed).

Offspring romantic relationship conflict

Offspring reported on conflict in their romantic relationships annually from age 18 through age 21 (see Appendix). We combined 4 years of outcome data to increase the stability of the conflict estimate. Additionally, because many offspring were not always in a relationship, we were able to evaluate relationship outcomes for a larger proportion of the offspring by considering multiple years. Seventy-two participants were not in a relationship during any of the four annual interviews from age 18 through age 21; thus, we excluded them from the analyses because we wanted to generalize to offspring in a dating relationship, which left us with a sample size of 513.1 Each year, participants were asked to consider their romantic relationship over the past year and to report separately how often they had engaged in various behaviors toward their romantic partner and how often their partner had engaged in these behaviors toward them. The age 18 measure was composed of 11 items originally included in the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). In the age 19 through age 21 interviews, a truncated version of the age 18 measure was given; this scale combined some behaviors (e.g., “pushed, grabbed, or shoved”) and used a different response scale than did the age 18 measure. Because the scales from age 19 through age 21 were not readily comparable with the age 18 scale, we standardized participants’ scores on each measure within each year and combined these four scales as indicators on a latent offspring relationship conflict construct. To account for missing data on individual items, we averaged all items to obtain the scale score for each year. At age 18, 35% of the offspring participants reported no conflict in their romantic relationship. For ages 19, 20, and 21, the percentage of reported zero scores was 19%, 9%, and 14%, respectively. Because of positive skew in these measures, scale scores were log transformed.

SIP

SIP constructs were assessed at ages 13 and 16 (Burks, Laird, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999; Fontaine, Burks, & Dodge, 2002; Lansford et al., 2006). Adolescent offspring were presented with a series of vignettes that depicted social interactions with a peer or adult that ended in an ambiguous provocation directed toward an adolescent protagonist (e.g., you want to sit at a lunch table with a group of kids, but they say “You can’t sit there”). The same vignettes were presented at both ages, although three cartoon stories presented at age 13 were not presented at age 16. Offspring were asked to imagine themselves as the protagonist of each situation. Both the age 13 and the age 16 assessments began with the presentation of six videotaped vignettes that featured adolescent actors. Three vignettes were gender neutral and were shown to all participants, and three vignettes were gender specific. At age 13, adolescents were shown nine additional vignettes in the form of line drawings while the experimenter read a scripted verbal description of the drawn event. At age 16, adolescents were shown six additional vignettes in the form of line drawings and audio-recorded narration of the drawn events. At both ages, adolescents answered questions that assessed SIP constructs after each vignette. The questions differed in format for the age 13 and age 16 assessments, but comparable constructs were assessed. Age 13 encoding, attributions, and response generation stages were assessed with open-ended questions. Interrater reliability was computed for a subsample of the collected data, r(96) = .86, .74, and .80 for Steps 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Age 13 response evaluation and all age 16 SIP constructs were assessed with closed-ended questions.

We assessed encoding at age 13 by asking participants to verbally recount important things that had happened in each vignette. We coded responses according to the amount of relevant information included (1 = fully relevant, 2 = partially relevant, 3 = nonrelevant) and averaged them across vignettes to create a single encoding score (α = .66). We assessed hostile attributions by asking participants why the event in each vignette had occurred. The score reflected the proportion of stories for which participants said that the event occurred because the other child was being mean (α = .54). We assessed response generation by asking what the participants would do if the depicted event happened to them and measuring the proportion of aggressive responses generated for each vignette (α = .71). Response evaluation was assessed by asking participants to report the likelihood that an aggressive response would lead to a desired outcome, how they would feel about themselves if they responded aggressively, and how much others would like them if they responded aggressively (α = .83).

Encoding was not assessed at age 16. We assessed hostile attributions by asking participants whether the actor in the vignette intended to be mean and how angry they would be if the depicted event happened to them (an indirect measure of attribution; α = .86). Rather than reuse the open-ended format with which we had measured response generation at age 13, we asked 16–year-old participants to choose between an aggressive and a nonaggressive behavioral response to each depicted situation. The response generation score at this age was the proportion of times that participants chose aggressive responses (α = .75). Both the aggressive and the nonaggressive hypothetical responses then were portrayed in live-action video or described by the audio narrator. Response evaluation was assessed through four questions presented after each of the aggressive hypothetical responses. The questions asked how good or bad the response was, how well acting this way would help the participants achieve their interpersonal goals, how well acting this way would help the participants achieve their instrumental goals, and how participants would feel about themselves if they acted this way. We averaged these four variables across depicted behavioral response options and vignettes to create the response evaluation measure (α = .88).

Missing Data

Due to missing data, sample sizes differed for each measure and ranged from 237 to 410 (see Table 1). Fifteen participants provided no data on any of the raw measures of interest and were thus excluded from the analyses, which left a final sample size of 498. Analysis of missing data patterns with SPSS missing value analysis suggested that data were not missing completely at random. Twenty of 210 contrasts (9%) attained a significance level of p = .05. The only pattern that emerged in the missing value analysis was a significant difference in SIP problems for offspring, which was based on whether their parents had or had not completed the parent conflict measures; offspring with missing parent conflict data were more likely to have more aggressive SIP patterns than were offspring with complete parent conflict data.2

To address issues of missingness in the data set, we used maximum likelihood estimation based on all available data, or full information maximum likelihood (FIML) parameter estimation, which utilizes all available data to estimate the coefficient of each parameter in the model. The FIML parameter estimation method does not perform data imputation for missing data points but includes all available data to produce covariance matrices necessary for model fit and parameter estimation. Although we found that some SIP indices were related to missingness, we are aware of no test to confirm that data are missing not at random. We assume our data are missing at random (MAR); however, FIML estimation is likely to produce valid estimates even when an assumption of MAR is erroneous (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). By including all available data, FIML estimation reduces bias relative to complete cases analysis.

Results

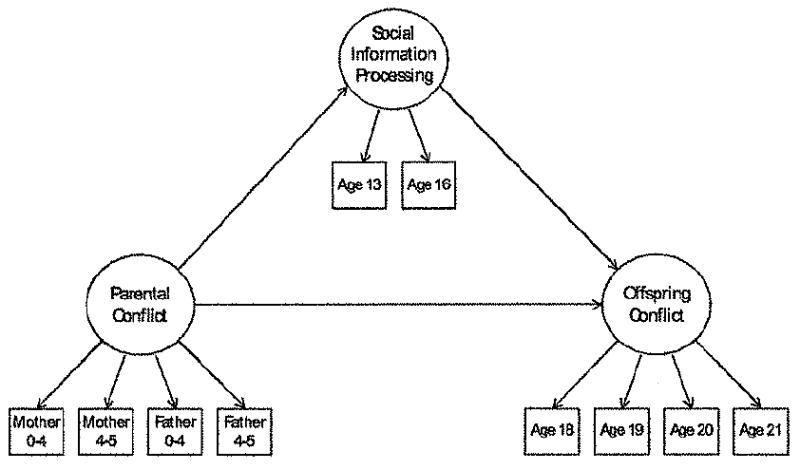

Bivariate correlations among individual scales and measures are presented in Table 1. We found modest correlations between some measures of parental relationship conflict and offspring SIP, modest correlations between some measures of parental relationship conflict and offspring relationship conflict, and modest to medium-sized correlations between some measures of offspring SIP and offspring relationship conflict. The lack of a more extensive pattern of correlations could be due to modest links between the concepts or to measurement error. We further explored relations between these constructs using structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999; Byrne, 2001), which allowed us to address issues of inadequate measurement by modeling latent variables and to address missing data with FIML parameter estimation. Although the four steps of the SIP model are often significantly correlated (see Table 1), they are theorized to be distinct constructs; thus, we tested them independently in a series of four separate models (see Figure 1 for a graphical representation of the general model).3

Figure 1.

General structural equation model testing individual social information processing steps as mediators of the association between interparental conflict and offspring romantic relationship conflict.

Model 1 tested the encoding stage as a mediator of the association between interparental conflict and offspring romantic relationship conflict. Because encoding was not measured at age 16, we included responses to each of the six stories presented at age 13 as observed factors of the latent encoding variable. Their inclusion produced a mediational construct with six observed indicators. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(73, N = 498) = 123.9, p < .001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .961, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .037, Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 215.92. The direct path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict was significant (β = .19, p = .01). However, parental conflict did not significantly predict encoding (β = .06, p = .43), and encoding did not significantly predict offspring relationship conflict (β = .03, p = .78), so the requirements for mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986) were not met for the encoding stage.

Model 2 tested the attribution of intent stage as a mediator. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(31, N = 498) = 62.1, p < .001, CFI = .971, RMSEA = .045, AIG = 130.09. The direct path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict showed a trend toward significance (β = .18, p = .08). Parental conflict did not significantly predict hostile attributions (β = .01, p = .94), and hostile attributions did not significantly predict offspring relationship conflict (β = .60, p = .11); thus, the requirements for mediation were not met for the attribution stage.

In Model 3, the response generation stage was tested as a latent mediator. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(31, N = 498) = 55.6, p = .004, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .040, AIC = 123.58. Following the methods outlined by Kenny (2006) for testing mediation in a SEM context, we estimated the direct, unmediated path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict before the inclusion of response generation into the model to be β = .211. In the mediational model, interparental conflict significantly predicted offspring response generation (β = .32, p = .02), and response generation significantly predicted offspring relationship conflict (β = .55, p = .01). In this model, the direct, mediated path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict was not significantly different front zero (β = .03, p = .77). Inclusion of response generation as a mediator reduced the association between parental conflict and offspring conflict from approximately .211 to virtually no relationship.4 To test for significance of mediation, we used a modified version of the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) that accounts for asymmetry of the distribution of the indirect effect (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). For a significance level of p = .05, the confidence interval for the unstandardized indirect effect did not include zero (upper limit = .741, lower limit = .026); hence, we found evidence of significant mediation in Model 3.

Finally, Model 4 tested the response evaluation stage as a possible mediator. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(31, N = 498) = 54.4, p = .006, CFI = .979, RMSEA = .039, AIC = 122.45. We estimated the original direct, unmediated path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict to be β = .195. In the full mediational model, interparental conflict predicted offspring response evaluation to a trend level (β = .15, p = .06), and response evaluation significantly predicted offspring relationship conflict (β = .46, p < .001). In the context of response evaluation as a mediator, the direct path between interparental conflict and offspring relationship conflict was not significant (β = .13, p = .09). Inclusion of response evaluation as a mediator reduced the original association by approximately 36%. We again used the method for testing significance of mediation outlined by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon et al., 2002, 2004). For a significance level of p = .05, the confidence interval for the unstandardized indirect effect had an upper limit of .275 and a lower limit of .001; thus, we found evidence of significant mediation in Model 4.

Perpetration and Victimization

Within each year, offspring reports of their own behaviors were highly correlated with reports of their partners’ behavior (rs ranged from .75 to .83, ps < .001). For the sake of completeness, however, we also performed all previously described SEM analyses separately, using only offspring-reported behavior from the target offspring to the partner (perpetration) and using only offspring-reported behavior from the partner to the target offspring (victimization). The path estimates and significance levels were the same when we compared the perpetration and victimization models to each other and when we compared the perpetration and victimization models to the combined models presented above. We found no evidence that the SIP mechanism operates differently for perpetration and victimization behaviors.

Gender Differences

We tested the above models separately for male and female participants. All fit statistics, path estimates, and significance levels were similar for male and female participants for Models 1–3 (encoding, hostile attributions, and response generation). In Model 4 (response evaluation), all fit statistics, path estimates, and significance levels were similar except for the path between interparental conflict and response evaluation. This path estimate was significant for male participants (β = .26, p = .03) but not for female participants (β = .04, p = .70). However, allowing this path estimate to differ by gender did not yield a significant improvement in model fit, Δχ2(1, N = 498) = 1.2, p = .27. Thus, we did not find evidence for significant gender differences in any of the above results.

Discussion

The present study provided support for the response generation and response evaluation stages of the SIP model as significant mediators between interparental conflict and young adult offspring romantic relationship conflict. Response generation tendencies in the offspring as an adolescent almost completely accounted for the association between parental and offspring relationship conflict. Response evaluation accounted for 36% of this association.

The response generation and response evaluation steps are conceptually similar and most likely influence each other reciprocally during processing. However, they are treated as separate theoretical constructs within the SIP model and may act as mediators in the parent–offspring relationship conflict association via distinct processes. Response generation refers to the types (aggressive, neutral, or proactive) of possible responses a child generates in reaction to a particular situation. Parents who engage in high levels of relationship conflict presumably model more aggressive and fewer nonaggressive responses and thus afford their children fewer opportunities to witness nonaggressive responses to provocative situations. These children may then enter their own romantic relationships as young adults with a less varied set of possible response options to provocative situations, which may lead them to engage in more aggressive conflict behaviors.

Response evaluation refers to the child’s estimation of what he or she might actually do in a particular situation and how effective this response might be in attaining goals. Children whose parents engage in aggressive conflict may have fewer opportunities to see the effectiveness of proactive response strategies in a variety of provocative situations. They may discern that aggressive responses end an argument between their parents, but they may have no idea whether gentler responses would yield a similar result.

The initial SIP stages, namely, encoding and attribution of intent, were not predicted by parent conflict and thus did not play a mediational role in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. We found no evidence that high levels of interparental conflict predisposed teens to pay less attention to relevant details of a situation or to attribute hostile intent to an ambiguous action, although previous work has found an association between husbands’ hostile attributions for negative behaviors in wives and marital violence perpetration (Holtzworth-Munroe, 2000). The lack of findings for the initial SIP stages may be at least partially a reflection of differences in internal consistency of the composite scales for the early SIP stages compared with the later SIP stages. Both the encoding measure, which was measured only at age 13, and the age 13 hostile attribution measure had lower scale consistencies than did the later SIP stages. Although the age 16 hostile attribution measure had higher internal consistency, it is possible that the lower internal consistency of the earlier measure contributed to error variance in these scores and limited our ability to find significance when we tested these models. However, testing separate models for age 13 and age 16 hostile attribution measures yields comparable model fit and finds no evidence for mediation. This finding suggests that the differences in internal consistency cannot solely account for the lack of findings.

Additionally, we may have found a stronger role for encoding had we measured attention to hostile or aggressive details rather than to general details. However, it is also possible that the earlier and later SIP stages do differ in the extent to which they are influenced by parental marital conflict. Pending replication, this pattern of null findings for the early SIP stages and positive findings for the later SIP stages in the current study may suggest the value of conceptually distinguishing between different stages of the SIP model, at least between the early and late stages.

We also found no evidence of mechanistic differences for perpetration and victimization within the dating relationship, even though previous research has often addressed them separately. It is possible that acting aggressive toward a romantic partner and “tolerating” aggressive behavior from a romantic partner share a common mechanistic pathway. Perhaps perpetrators and victims of relationship aggression view aggressive conflict as more acceptable than others do, partly as a result of their lowered generation of alternative responses to conflict and their beliefs in the effectiveness of aggression. It may be that the product of parental conflict is a disposition to become involved in aggressive relationships rather than to specialize in either perpetrating or being victimized by relationship violence (Murphy & Blumenthal, 2000).

Alternatively, perpetration and victimization are often highly correlated within individuals, as is the case in our sample; men and women who report engaging in more relationship aggression are more likely also to report their partner engaging in more relationship aggression. This “assortative partnering” phenomenon (Capaldi et al., 2004) may have prevented us from meaningfully separating perpetration and victimization behaviors in our data set. It has also been reported that almost one half of violent conflicts in romantic relationships involve both men and women being physically aggressive (Capaldi et al., 2004); thus, the roles of perpetrator and victim may not be as clear cut as is often assumed. Furthermore, the most serious conflict behaviors (i.e., physical violence) had the lowest reported incidence within our sample. The majority of conflict behaviors being reported were indicators of verbal conflict (e.g., shouted or yelled at my partner). Partners are very likely to engage in these lower level conflict behaviors toward each other in reciprocity, which may also explain me high degree of correlation between offspring and partner conflict behaviors in our sample. Nevertheless, a more in-depth study of conflict behaviors within different romantic relationships may allow future researchers to more accurately tease apart these highly correlated but conceptually distinct constellations of behavior.

This study of SIP constructs as mediators in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict had several important strengths. First, we used prospective data from multiple reporters, which decreased potential shared method variance and retrospective reporting biases. Most previous work has relied upon retrospective reports by children of parental conflict measured at the same time point as their own relationship conflict. Second, we provided a direct test of mediation using a mediator that was measured temporally before the outcome variable. Third, our analyses represent both male and female participants, whereas many studies in the past have focused on men. Finally, we systematically explored four SIP steps in one study using the same data set.

Several limitations must be addressed. As with any research involving parents and their children, genetic explanations must be considered. In this case, genetics may act as a sort of “fourth variable” that underlies the association between the relationship conflict and SIP. This does not reduce our interest in the specific phenotypes, but it reminds us that there may be other levels of description of developmental process. There are, of course, other potential mediators in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. For example, evidence has recently been found in support of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as a mediator of the association between childhood maltreatment and adolescent dating abuse (Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004). Witnessing interparental conflict as a child may be associated with later trauma symptoms, which may then mediate the association between interparental conflict and later romantic relationship abuse. Another possible mechanism that has garnered attention is rejection sensitivity, which is the disposition to anxiously expect, readily perceive, and intensely react to rejection (Downey & Feldman, 1996). Interparental conflict in the family of origin may lead children to be hypervigilant to rejection cues from their romantic partner, which would increase the likelihood of their engaging in abusive behavior.

Methodological limitations of the current study should be considered. Our measure of SIP included four steps. Measures of internal consistency for the first two steps in the age 13 assessment were lower than those for the last two steps. As discussed above, the lower internal consistency of the earlier measures may have limited our ability to test mediation accurately in these models. Additionally, the vignettes we used to measure SIP at ages 13 and 16 were not specifically tailored for dating relationships but were designed more generally to reflect interactions with peers and authority figures. It is possible that the use of domain-specific SIP measures would yield stronger results. Previous research in the marital violence literature has utilized vignettes specifically depicting marital conflict to measure interpretation and decision making. Such research has found that maritally distressed and maritally violent men are more likely than are nonviolent men to attribute hostile intent to negative wife behavior, and violent men appear to generate less competent responses to marital conflict vignettes (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990; Holtzworth-Munroe, 2000). However, it is possible that domain-specific SIP measures would be more useful in studies of stable relationships and that more general SIP measures, such as those employed in the current study, serve to give a more global view of the individual’s SIP tendencies across relationships. Finally, our measures of relationship conflict looked broadly at all levels of conflict and did not focus on physical aggression. However, even lower levels of aggression, such as psychological control and verbal aggression, can be deleterious to a relationship and can predict the onset of physical aggression (Murphy & O’Leary, 1989); thus, study of all levels of conflict is important.

In conclusion, this study has provided support for the response generation and response evaluation stages of the SIP model as significant mediators of the association between interparental conflict and young adult offspring romantic relationship conflict. These findings contribute to a more detailed developmental model of the process by which problems in intimate relationships can be transmitted across generations.

Acknowledgments

The Child Development Project has been funded by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH42498, MH56961, MH57024, and MH57095 and by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD30572. Age 16 assessments were supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation to the National Consortium on Violence Research. We are grateful to the parents, children, and teachers who have participated in this research, as well as to the many Child Development Project staff members. We thank Jennifer Lansford and Jackson Goodnight for their contributions to this article.

Appendix

Relationship Conflict Scales

Mother and Father, Year 1

Argued heatedly but didn’t yell

Yelled, insulted or swore at your husband/wife

Sulked and/or refused to talk about it

Stomped out of the room or house

Threw, smashed, hit or kicked something

Threatened to throw something at your husband/wife

Threw something at your husband/wife

Pushed, grabbed, or shoved your husband/wife

Threatened to hit your husband/wife

Hit or tried to hit your husband/wife

Hit or tried to hit your husband/wife with something

Offspring, Age 18

Insulted or swore at my boyfriend/girlfriend

Shouted or yelled at my boyfriend/girlfriend

Threw something at my boyfriend/girlfriend

Destroyed something belonging to my boyfriend/girlfriend

Pushed or shoved my boyfriend/girlfriend

Grabbed my boyfriend/girlfriend

Threatened to hit or throw something at my boyfriend/girlfriend

Twisted my boyfriend/girlfriend’s arm or hair

Punched or hit my boyfriend/girlfriend with something that could hurt

Slapped my boyfriend/girlfriend

Kicked my boyfriend/girlfriend

Offspring, Age 19–21

Argued heatedly but didn’t yell

Yelled, insulted or swore

Sulked or refused to talk about it

Stomped out of the room or house

Threatened to throw something

Pushed, grabbed, or shoved

Hit

Footnotes

Including these 72 offspring in the analyses described below did not meaningfully change the pattern of results found for any model. However, because they did not provide valid outcome data, these participants were not included in the reported analyses; thus, generalizability to individuals who initiate romantic relationships after age 21 is unknown.

We created summary variables to reflect whether the participant had parent data available for each of the four parental subscales. When correlated with the SIP and offspring conflict indicators, all associations were modest-to-moderate in size (rs < .24), which suggests that missingness in parent conflict variables was not strongly related to the other variables in the model.

There are two other possible approaches to these analyses. First, all four separate SIP steps can be tested simultaneously in one comprehensive model (as done by Dodge et al., 2003). We performed this analysis and found that the model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2 (73, N = 498) = 120.7, p < .001, comparative fit index = .967, root-mean-square error of approximation = .036, Akaike information criterion = 244.69. Interparental conflict significantly predicted response evaluation (β = .20, p = .04) and predicted response generation to a trend degree (β = .43, p = .09); no other paths between constructs were significant. Thus, the requirements for mediation were not met. This may have been due to significant intercorrelations, and thus overlapping variance, between SIP constructs. The second approach involves creation of one latent SIP construct, with all measured stages from ages 13 and 16 included as observed factors. This model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(86) = 126.0, p = .003, comparative fit index = .972, root-mean-square error of approximation = .031, Akaike information criterion = 225.99. SIP significantly predicted offspring relationship conflict (β = .42, p = .02). Trend-level associations were found between parental conflict and SIP (β = .17, p = .08) and between parental conflict and offspring conflict (β = .13, p = .08). The initial, unmediated path between parental conflict and offspring relationship conflict was estimated to be β = .196. Inclusion of SIP as a mediator reduced this association by 35%, which was significant at p < .05 when we used the MacKinnon test for mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2002, 2004). However, we rejected this model, due to low factor loadings for encoding, hostile attributions, and response generation from the age 13 assessment.

The mediational model was not directly compared with a more parsimonious model, which included all relevant constructs but excluded the pathway between the proposed mediator and the outcome variable, because the factor loadings would not be equivalent between models. Thus, the models are not comparable (see Kenny, 2006, for a more thorough discussion of testing mediation in a SEM context).

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. Fite, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University

John E. Bates, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University

Amy Holtzworth-Munroe, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Sandra Y. Nay, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Gregory S. Pettit, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Auburn University

References

- Amato PR, Booth A. The legacy of parents’ marital discord: Consequences for children’s marital quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:627–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 users guide. Chicago: Smallwaters; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. Attributions in marriage: Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:3–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Wanner B. Parent and peer effects on delinquency-related violence and dating violence: A test of two mediational models. Social Development. 2002;11:225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Anthony C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Gerard J, Pemberton S. Interparental conflict and youth problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Burks VS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Knowledge structures, social information processing, and children’s aggressive behavior. Social Development. 1999;8(2):220–236. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In: Putallaz MA, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford; 2004. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam C. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Delsol C, Margolin G. The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:99–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. A social information processing model of social competence in children. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. Vol. 18. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Do social information-processing patterns mediate aggressive behavior? In: Lahey B, Moffitt T, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 254–274. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990 Dec 21;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, Price JM. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:339–357. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Understanding the association between marital conflict and child adjustment: Overview. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine RG, Burks VS, Dodge KA. Response decision processes and externalizing behavior problems in adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:107–122. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social position. Yale University; 1979. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A. Social information processing skills deficits in maritally violent men: Summary of a research program. In: Vincent JP, Jouriles EN, editors. Domestic violence: Guidelines for research-informed practice. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Bates L, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Norwood WD, Ware HS, Spiller LC, Swank PR. Knives, guns, and interparent violence: Relations with child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Mediation. 2006 Feb 7; Retrieved March 14, 2006, from http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm.

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Malone PS, Dodge KA, Crozier JC, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A 12-year prospective study of patterns of social information processing problems and externalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:709–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter EL, McCloskey LA. The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:344–357. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Blumenthal DR. The mediating influence of interpersonal problems on the intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Leary KD. Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:579–582. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M, Chin C. The relationship between children’s reported exposure to interparental conflict and memory biases in the recognition of aggressive and constructive conflict words. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological context, and children’s adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68(5):908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wolfe DA. Predictors of relationship abuse among young men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson SB, Upchurch DM, Shen H. Violence and injury in marital arguments: Risk patterns and gender differences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:35–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaccarelli S, Coatsworth JD, Bowden BS. Exposure to serious family violence among incarcerated boys: Its association with violent offending and potential mediating variables. Violence and Victims. 1995;10:163–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:640–654. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman A, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]