Abstract

Mammalian infant behavior directed toward caregivers is critical to survival and may play a role in establishing social bonds. Most mammalian infants vocalize when isolated. Rat pups vocalize at a higher rate when isolated following an interaction with an adult female than after an interaction with littermates, a phenomenon termed maternal potentiation. We previously reported that the D2 receptor family agonist quinpirole disrupts maternal potentiation at a dose that does not alter vocalization rate following contact with littermates. Here we further examine the role of dopamine in maternal potentiation by testing effects of both D1 and D2 receptor family ligands, alone and in combination, on maternal potentiation. We tested the drugs’ effects on isolation vocalization subsequent to littermate contact and then another isolation preceded by a brief “reunion” period of exposure either to the anesthetized dam or a handling-only “pickup” condition. D2 receptor stimulation blocked the increase in vocalizations following reunion with the dam. The D2 agonist effect in the dam-reunion condition was much larger than its small effect in the pickup condition, providing further evidence that D2 receptors exert a selective modulation of maternal potentiation. On the other hand, systemic administration of the D1 agonist SKF81297 reduced isolation vocalizations nonspecifically, across all the experimental conditions. Finally, the D1 and D2 receptor dual antagonist, alpha-flupenthixol, increased isolation vocalizations and disrupted potentiation, but at doses that also inhibited locomotion. We conclude that D2 receptor family activation has a more selective effect of disrupting maternal potentiation than D1 receptor family activation.

Keywords: rat, social behavior, isolation vocalization, dopamine, D1 receptor, D2 receptor, infant, maternal potentiation

INTRODUCTION

In many mammalian species, the young cry in response to isolation. The vocalizations elicit retrieval and other maternal behavior (Smith & Sales, 1980). If isolated immediately after contact with their anesthetized dam, rat pups vocalize at a substantially higher rate than in an isolation preceded only by contact with littermates (maternal potentiation) (Hofer, Brunelli, & Shair, 1994). For dam-reared pups, only their dams or another adult female can induce potentiation. But, for pups reared with both dam and sire, a brief reunion with either parent potentiates vocalization in the following isolation (Brunelli, Masmela, Shair, & Hofer, 1998). Hence, the potentiation phenomenon is selectively evoked by con-specifics which share, through caregiving behavior, the capacity to promote the pup’s survival. For these reasons, it has been used as a marker for infantile attachment (Moles, Kieffer, & D’Amato, 2004). As discussed in a recent review by Shair (2007), maternal potentiation offers an important behavioral paradigm to understand the neurobiology of motivated social behavior in the infant.

Dopamine plays a role in adult mammalian social behavior (Stern & Lonstein, 2001; Wang et al., 1999), as well as infant isolation-induced vocalization (Dastur, McGregor, & Brown, 1999; Kehoe & Boylan, 1992). However, the role of dopamine in infant social interactions has only just begun to be investigated. We have demonstrated that quinpirole, an agonist of the D2 receptor family (consisting of the D2, D3, and D4 subtypes), disrupts maternal potentiation of vocalization at doses that do not affect isolation calling that were not preceded by maternal contact (Muller, Brunelli, Moore, Myers, &Shair, 2005). Moreover, the ventral striatum is a critical site for the D2 agonist’s disruption of potentiation (Muller, Moore, Myers, & Shair, 2008). On the other hand, prior work showed that systemic injection of an agonist of the D1 receptor family (consisting of the D1 and D5 subtypes) reduced isolation-induced vocalizations, whereas no effect of a D1 antagonist was observed (Dastur et al., 1999). However, the role of D1 receptor family activity in maternal potentiation was previously unknown. Thus, in the present study, we further examined the role of dopamine in maternal potentiation by testing the effects of selective stimulation or antagonism of the D1 receptor family and comparing the results to the effects of D2 receptor family manipulation in an expanded behavioral testing paradigm that includes an additional control for the inherent consequences of the repeated testing design and the effects of sensory stimulation associated with experimenter handling of the subject during the reunion.

We also examined the possibility that the effects of dopamine receptor family-selective agonists, in regulating maternal potentiation of isolation-induced vocalization, depend upon the interaction of D1 and D2 receptor families. There are examples of serial interactions at the neurophysiological level (Rahman & McBride, 2001; Walters, Bergstrom, Carlson, Chase, & Braun, 1987) and on behavior (Canales & Iversen, 2000; McDougall, Crawford, & Nonneman, 1992; Phillips, Howes, Whitelaw, Robbins, & Everitt, 1995). Thus, we tested whether inactivation of D1 receptors would alter the disruption of maternal potentiation by D2 receptor activation. Similarly, we determined whether antagonism of D2 receptors, which by itself has no effect on potentiation (Muller et al., 2005), would change the effects of D1 receptor ligands on maternal potentiation.

Finally, we examined the effect of combined systemic inactivation of both D1 and D2 receptors, since nothing was known about such dual antagonism on maternal potentiation. Our prior work showed that the D2 antagonist alone had no effect on maternal potentiation (Muller et al., 2005). It could be that endogenous activity at either D1 or D2 receptors alone is sufficient to permit maternal potentiation. By simultaneously blocking activity of each receptor family, we tested the hypothesis that some minimal endogenous activation of either D1 or D2 receptor families is necessary for maternal potentiation.

Together with our companion article (Shair, Muller, & Moore, in press), the present article represents a comprehensive study of the role of endogenous dopaminergic tone or excess stimulation at D1 and D2 receptors on the modulation of isolation vocalization by social stimuli.

METHODS

All animal care and procedures were consistent with government regulations and approved by the IACUC committee at the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Subjects

Ninety-two dams from a Wistar derived breeding colony (founders obtained from Hilltop Farms) and their litters were used. Pregnant females were brought to a satellite housing 3 days prior to expected delivery date. The day of birth was considered postnatal day (PND) 0. Pups were culled to 5 male and 5 female on PND 1. Litters not producing 10 pups or not having at least 4 pups of each sex were excluded. Subjects were tested at PND 12 or 13. Subjects were tested in 8 cohorts. Within each cohort, a litter supplied either a single pup to each test condition, or two pups whose results were averaged. In the final two cohorts, a pretesting axial temperature was taken—a procedure not used in the other 6 cohorts.

Drugs

For the purposes of these studies, “D2 receptor” or “D2 receptor family” refer to the pharmacological class of dopamine D2 receptors including D2, D3, and D4 receptor subtypes, and the term “D1 receptor” or “D1 receptor family” refers to the class of dopamine receptors including D1 and D5 subtypes. Concentrated stock solutions of all drugs were prepared by dissolving the drugs in de-ionized water and stored at −80°C. Physiologic saline (.9% NaCl) was prepared and used to mix with stock drug solutions to prepare the final concentrations, which were drawn up into 1 ml syringes with 30 g needles and frozen at −80°C. Syringes were removed from the freezer 20 min prior to experimental use to allow for thawing. All syringes were shielded from light exposure until used. All solutions were prepared for a delivery volume of .1 ml per 30 g of body weight. Doses of D2 receptor agonists and antagonists were based on previous studies (Muller et al., 2005, 2008). Doses of the D1 receptor agonist SKF81297 and the D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 and nonselective dopamine receptor antagonist alpha-flupenthixol were chosen to cover a range of concentrations previously reported to affect rodent behavior (Bayer, Brown, Mactutus, Booze, & Strupp, 2000; Dickinson, Smith, & Mirenowicz, 2000; Dunn, Futter, Bonardi, & Killcross, 2005; Izquierdo et al., 2006; Szczypka, Zhou, & Palmiter, 1998; Tinsley, Rebec, & Timberlake, 2001).

Experimental conditions were grouped into four experiments. Two control groups—vehicle injections administered to a dam-reunion group and a pickup-control group—were used in all four experiments. Experiment 1, testing the effects of D2 receptor activation, had two additional groups: a dam-reunion group and a pickup control group each administered the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Experiment 2, testing D1 receptor activation and inactivation, had eight additional groups: four groups of the D1 agonist SKF81297 (doses of 1 and 3 mg/kg—each dose administered to a damreunion group and a pickup-control group), three groups administered the D1 antagonist SCH23390 (.3 and 1.5 mg/kg dose group in the dam-reunion condition and a pickup-control group with the .3 mg/kg dose), and finally, a group that had both the D1 agonist dose of 1 mg/kg and the D1 antagonist at a dose of .3 mg/kg. Experiment 3, testing dopamine receptor interactions, had two additional groups: one group was administered both the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole at a dose of 1 mg/kg and the D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 at a dose of .3 mg/kg; the other group was administered both the D1 receptor agonist SKF81297 at a dose of 1 mg/kg and the D2 receptor antagonist raclopride at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Experiment 4, testing the effects of combined inactivation of both D1 and D2 receptors, had six additional groups: for the dam reunion condition, four groups were administered the dual D1 and D2 receptor antagonist, alpha-flupenthixol at doses of .01, .1, .33, and 1 mg/kg; a pickup control group was administered flupenthixol at the .33 mg/kg dose level; finally, a dam-reunion group was administered the combination of D1 and D2 receptor selective antagonists (.3 mg/kg dose of SCH23390 and 1 mg/kg dose of raclopride).

Testing Preparation and Drug Injection

Litters were tested on PND12 or 13 during the light phase of their 12/12 h light/dark cycle. The dam was removed from the home cage. The litter, still in the homecage, was placed on a thermoregulated heating pad that maintained normal nest temperature. Every 10 min, a pup was weighed, marked with ink on the dorsal fur for identification, and injected. Drug condition was randomly counterbalanced across order of injection. If there were two injections, they were 10 min apart. If the two injections were an antagonist and an agonist, the antagonist was administered first. Depending on the drug group, experimental pups received 1 or 2 injections. Control pups received 0, 1, or 2 injections. An ANOVA of vocalizations in the first isolation (ISO1) for vehicle dam-reunion subjects from cohorts 1–3 showed that the number of injections had no effect, F(2, 54) = .36, p = .7; nor did number of injections affect the change in vocalization rate from ISO1 to the second isolation (IS02), F(2, 54) = .35, p = .71). Thus, a single-injection vehicle group was used in subsequent cohorts. In all other respects, the procedures among the cohorts were the same.

Behavior Testing Procedure

We used a paradigm for assessing maternal potentiation that has been used repeatedly in our laboratory (Brunelli et al., 1998; Hofer & Shair, 1978; Hofer et al., 1994; Shair, Brunelli, Masmela, Boone, & Hofer, 2003). In our prior study of the effect of a D2 receptor family agonist on potentiation (Muller et al., 2005), the D2 agonist prevented the normally observed difference in vocalization between an initial isolation without prior maternal contact and vocalization in a re-isolation after dam-contact. The effect of the D2 agonist could have been due to the its effect on neural activity related to recent dam-contact, or from the drug’s effect on other factors related to the repeated testing design, such as habituation to the isolation period or passage of time. Although prior work had demonstrated for un-injected subjects that repeated testing design itself did not account for the underlying phenomenon of maternal potentiation (Hofer et al., 1994; Shair, 2007), we could not rule out that repeated testing effects influenced the apparent effects of D2 receptor stimulation in the previous study. Thus, the present study included a “pickup” control condition in which pups were exposed to the standard initial isolation, reunion, and re-isolation periods except that, during the “reunion” phase, pups were handled but not exposed to the dam.

Beginning at 30 min after its last injection, each experimental pup was observed during an initial isolation (ISO1), a brief reunion with its anesthetized dam (or no reunion for “pickup” controls), and a second isolation immediately following the reunion (ISO2). For ISO1, a pup was picked up and placed in a clean polycarbonate box (18 cm × 21 cm × 20 cm) the underside of which was marked to produce six equal squares. During ISO1, the pup was alone for 2 min. Then, for the maternal potentiation condition, a pup was picked up, the anesthetized dam was put in the box, and the pup was placed back in the box in contact with the dam for the 2 min of reunion. Finally, the dam was removed and the pup re-isolated for 2 min (ISO2). For “pickup” control groups, the pup was picked up at the beginning and end of a 2 min “reunion” period between the two isolation periods, but its dam was not placed in the test box during that period.

In groups in which we expected that the drug would block potentiation, we also included an additional test to address whether an absence of potentiation arose from a ceiling effect. In these tests, immediately following the re-isolation phase, pups were placed individually in the test box for 2 min and observed as before, except that the observation box was in a 10°C chamber, a condition known to increase vocalizations.

Ultrasonic vocalizations were detected with a bat detector (Pettersson Elektronik, AB, Uppsala, Sweden), transduced into an audible range, and counted with a hand operated counter. Other behaviors measured included square crosses, 360° turns-in-square, rearing (raising of the head above shoulder level and one or both front paws raised off the floor against the wall or in the air), and self-grooming (a bout of repeated dragging of one or both forepaws across the snout). All counts of square crosses, rears, and turns-in-square in each of the 2 min isolation periods were summed to give an overall locomotor activity score. When the dam was present, duration of time in contact with the dam was recorded. Ambient temperature was recorded immediately before and after each pup’s test. At the conclusion of each pup’s test, its axial temperature was measured.

Data Analysis

Overall analyses of variance (ANOVA) compared changes in behavior within subjects between test periods (ISO1, ISO2) and between groups which were distinguished both by reunion condition (Dam or Pick-up Control) and drug condition. When the overall ANOVA had a significant effect, post hoc analyses were used to identify which relevant groups differed. Dunnett’s post hoc test, in which each experimental group is compared to a single control group, was commonly used. Other statistics were also used, and described where the results are reported.

Consolidation of Data From Sexes and Vehicle Groups

There was no effect of sex on initial isolation vocalization or on potentiation (F(1, 733) = .578, p = .45 and F(1, 733) = .129, p = .72, respectively); nor was there an interaction of sex with reunion and drug conditions on initial isolation nor on potentiation (F(35, 733) = 1.38, p = .074 and F(35, 733) = .81, p =.78, respectively), replicating previous work (Brunelli, Keating, Hamilton, & Hofer, 1996; Brunelli, Vinocur, Soo-Hoo, & Hofer, 1997; Muller et al., 2005). Thus, male and female data were combined for all analyses reported.

This report included a number of cohorts, giving rise to a large amount of vehicle data, which were pooled for the analyses reported below: 112 dam-reunion subjects and 47 pickup controls. Comparing experimental conditions composed of subjects from different litters could have introduced differences between groups due to differences in litters rather than differences from the experimental conditions we were trying to test. If there were litter differences large enough to affect our results, however, we would expect that, in the combined vehicle group, mean rate of isolation vocalizations would differ by cohort. This was not the case. For the dam-reunion vehicle group, a condition present in every cohort (hence, sampling every litter), there were no significant differences in maternal potentiation scores among the cohorts F(7, 104) = 1.24, p = .29.

Please note that, for a subset of the subjects in this article, the initial isolation data is also reported in the companion article (Shair et al., in press). The unique aim of the present article is to study maternal potentiation: the difference in vocalization between the initial and re-isolation. In the companion article, the initial isolation data is used to assess contact quieting: the reduction of vocalization in the reunion period as compared to the initial isolation. Second, littermates of some subjects here provided data for the companion article. Those littermates were tested in a littermate-reunion condition, the data from which are reported exclusively in the companion article.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Examination of the Effect of D2 Receptor Family Activation on Maternal Potentiation

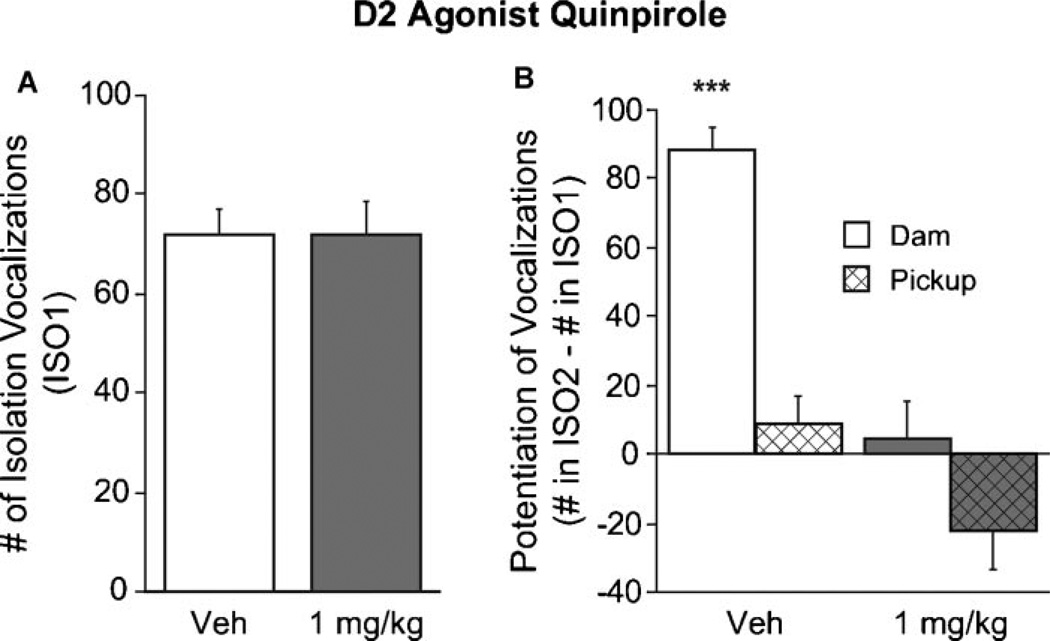

In this experiment, we tested whether the lower amount of vocalizations in ISO2 following administration of a D2 receptor agonist (compared to vocalizations in ISO2 following vehicle administration) depends on the exposure to the dam during the reunion. Thus, we administered quinpirole (1 mg/kg, i.p.) to a dam-reunion group (n = 38) and a pickup control group (n = 27), measured vocalizations during the isolation and re-isolation, as described in Methods Section, and compared these results to those for vehicle administration in both dam-reunion and pickup control groups.

Quinpirole disrupted maternal potentiation. In the ANOVA of vocalizations by isolation period, drug condition, and reunion condition, the three-way interaction was significant, F(1, 220) = 5.3, p = .023 (see Fig. 1B). Pairwise post hoc comparisons of ISO2–ISO1 scores (by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) method) showed that the vehicle dam-reunion group differed significantly from all three others at the p < .0001 level, and there were no significant differences among the other groups. Only the vehicle-treated, dam-reunion group showed potentiation, t(111) = 11.7, p < .0001. There was no significant change in vocalization rate in the quinpirole group, t(37) = .51, p = .61, nor in the pickup vehicle group t(46) = 1.1, p = .29. There was a reduction in vocalization in the D2 pickup group t(26) = 2.1, p = .041. Also, as previously reported (Muller et al., 2005), no groups differed in the initial isolation F(1, 220) = .1, p = .75 (see Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of a D2-family agonist on isolation vocalization and maternal potentiation of isolation vocalization. (A) Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min initial isolation (ISO1). Injection with the D2 agonist quinpirole at a dose that effectively disrupts maternal potentiation did not alter vocalization rate in the initial isolation. ns, nonsignificant. (B) Mean (±SE) difference in number of vocalizations between an initial isolation and a re-isolation (ISO2–ISO1) that followed 2 min “reunion” phase either with the anesthetized dam or pickup condition (pup handling as in the dam-contact reunion, but without the dam). Only the vehicle dam-reunion group showed potentiation (p < .0001) and was statistically different from each of the other groups at p < .0001 (indicated by asterisks, “***”). The other three groups were not significantly different from each other.

There may have been a small effect of the drug over the ISO1 through ISO2 time period and on cold-environment vocalizations. There was a trend for the potentiation scores of the quinpirole-treated pickup group to be lower than the vehicle pickup group (post hoc, Fisher LSD p = .085). Additionally, the D2 agonist may have reduced vocalization in the cold environment: the ANOVA of vocalizations in the cold between 1 mg/kg D2 agonist group and vehicle group was at the trend level, F(1, 23) = 3.6, p = .07 (see Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of a D2-family agonist quinpirole on isolation vocalizations in 10°C. Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min isolation in the cold environment. There was a trend for the D2 agonist to reduce vocalization in the cold. “t” indicates trend.

Experiment 2: Examination of the Effect of D1 Receptor Family Activity on Maternal Potentiation

To examine the role of D1 receptor activity in maternal potentiation, we tested the effects of systemically administered agonists and antagonists selective for the D1 receptor family. We tested dam-reunion groups treated with the D1 agonist SKF81297 at doses of 1 mg/kg (n = 32) and 3 mg/kg (n = 32), and pickup control groups for each of the same doses (n = 10 for each dose). To test the role of endogenous transmission at D1 receptors, the D1 antagonist SCH23390 at doses of .3 mg/kg (n = 31) and 1.5 mg/kg (n = 12) was tested for dam-reunion groups. A pickup control group was tested with a .3 mg/kg dose (n = 19). Finally, there was a group (n = 10) that had both the 1 mg/kg dose of the D1 agonist and a .3 mg/kg dose of the D1 antagonist. See Methods Section for further details.

D1 Receptor Family Activation Reduced Many Parameters of Isolation Vocalizations, Including Maternal Potentiation

Analyzing the effects of the D1 receptor agonist, SKF 81297, a three-way ANOVA revealed no interactions among testing phase, reunion condition and dose of drug, F(2, 237) = 1.2, p = .31. However, the D1 agonist did reduce vocalization across all testing period and reunion conditions: there was a main effect of drug condition, F(2, 237) = 10.5, p < .0001. See Figure 3. Consistent with the effect of the D1 agonist on vocalizations in the initial and re-isolations, the agonist also reduced isolation vocalizations for dam-reunion pups that were tested in a cold environment: F(2, 41) = 15.3, p < .0001. Dunnett’s post hoc test showed that vocalization in the cold for both the 1 and 3 mg/kg dose groups was significantly lower than in the vehicle group (p < .01). The 3 mg/kg dose group’s vocalization rate in the cold was significantly lower than the 1 mg/kg dose group’s: t(24) = 2.46 (see Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of a D1-family agonist on isolation vocalizations and maternal potentiation of isolation vocalization. (A)Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min initial isolation (ISO1). Injection with the D1 agonist SKF81297 reduced vocalization in a dose dependent manner. The 3mg/kg dose was significantly lower than vehicle (*p < .05). (B) Mean (±SE) difference in number of vocalizations between an initial isolation (ISO1) and a re-isolation (ISO2) that followed a 2 min period either with the anesthetized dam or without (“pickup” control). Compared to the appropriate vehicle control group, the D1 receptor agonist lowered the vocalization change score in most dose and reunion conditions. The “+” symbol indicates a significant difference from 0 for that group, at least p < .05; “t” (trend) indicates p < .1. Asterisks indicate that a dam-reunion drug-injected group is significantly less than the dam-reunion vehicle group by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *p < .05, **p < .01.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of a D1-family agonist on isolation vocalizations in a cold environment (10°C). Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min isolation at 10°C. Vocalization in both the 1 and 3 mg/kg dose groups was significantly lower than the vehicle group (**p < .01). The 3 mg/ kg dose group’s vocalization rate was significantly lower than the 1 mg/kg dose group’s, °p = .021.

To further characterize the D1 agonist’s general reduction of isolation vocalization, its effects were examined in three conditions: in the initial isolation, in re-isolation among the pickup-controls, and in the potentiation scores of dam-reunion groups. The D1 agonist reduced vocalization during the initial isolation, F(2, 240) = 3.0, p = .051.Dunnett’s post hoc analysis showed the 3 mg/kg dose group had significantly fewer vocalizations than the vehicle group, p < .05 (see Fig. 3A). Similarly, the D1 agonist altered the change in vocalization rate from the initial isolation to the re-isolation for both pickup controls and dam-reunion conditions. Among pickup controls, there was a significant effect of drug condition on the change score, F(2, 86) = 4.7, p = .012 (see hatched bars in Fig. 3B). The 1 mg/kg dose pickup group showed a reduction in vocalization, but the 3 mg/kg and vehicle pickup groups did not show significant change in vocalization between isolations (1 mg/kg: t(31) = 3.1; p = .0046; 3mg/kg: t(9) = .78; p > .45; Vehicle: t(46) = 1.1, p > .29). The D1 agonist also reduced maternal potentiation scores (see open bars in Fig. 3B) among the dam reunion groups: F(2, 151) = 8.0, p = .0005. Vehicle and 1 mg/kg dam-reunion groups showed potentiation (Vehicle: t(111) = 11.7, p < .0001; 1 mg/kg: t(31) = 3.5, p = .0013); there was a trend for the 3 mg/kg dose dam-reunion group toward potentiation as well (t(9) = 2.0, p = .071). Dunnett’s test showed both the 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg dam-reunion groups had smaller potentiation scores than the vehicle dam-reunion group (p < .01 and p < .05, respectively). Thus, although there was a significant effect of the D1 agonist on potentiation, this effect on potentiation is accounted for by the drug’s general reduction of isolation vocalization, as evidenced by the absence of an interaction of testing phase, reunion condition, and drug condition.

To demonstrate that the D1 receptor agonist effect on potentiation arose from its activity at the D1 receptor family, we examined the capacity of a D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 to reverse the agonist’s effect. The group with the combination of D1 agonist and D1 antagonist (n = 10) had mean vocalizations (±SE) of 83 ± 22 in ISO1 and 197 ± 29 in ISO2, which can be compared to the D1 agonist and vehicle results shown in Figure 3. Thus, the antagonist restored potentiation levels to those of vehicle. The ANOVA of potentiation score for the three groups was significant, F(2, 151) = 6.2, p = .0025. Post hoc Dunnett’s test showed that the D1 agonist group had a decrease in potentiation (statistically lower score than the vehicle group), but the combined D1 antagonist and agonist condition was not statistically different than vehicle-treated pups. None of the groups differed in initial isolation vocalization: F(2, 151) = .13, p = .88.

Antagonism of Endogenous Transmission of the D1 Receptor Family Did Not Affect Maternal Potentiation at a Dose That Increased Vocalization in General

Administration of the D1 antagonist SCH 23390 increased isolation vocalization (F(1, 205) = 34.3, p < .0001), but did not demonstrate an effect on maternal potentiation: the three-way interaction of isolation period, reunion condition, and drug condition was not significant, F(1, 205) = 2.3, p = .13 (see Fig. 5). The ANOVA of vocalization by isolation period among the dam-only groups (for which the higher dose of the antagonist was included), also showed no effect on maternal potentiation, F(2, 152) = 1.4, p = .24. The potentiation score was significantly different than 0 for the vehicle and .3 mg/ kg dose groups: Vehicle group t(111) = 11.7, p < .0001; .3 mg/kg group t(30) = 6.1, p < .0001. The 1.5 mg/kg dose group did not show a significant potentiation: score ≠ 0, t(11) = 1.61, p = .14.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of the D1 antagonist SCH23390 on initial isolation and maternal potentiation of isolation vocalization. (A) Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min initial isolation (ISO1). The D1 antagonist elevated ISO1 vocalization rate above the rate in the vehicle group (**p < .01). (B) Mean (±SE) change score (labeled “potentiation”) in number of vocalizations between the re-isolation and ISO1. For vehicle and .3 mg/kg dose conditions, pickup control groups are included, in addition to the dam-reunion groups for all drug conditions. There was no effect of the antagonist on potentiation. “+” indicates ISO2–ISO1 is significantly different than 0.

D1 Receptor Family Ligands’ Effects on Nonvocalization Measures

The D1 receptor agonist reduced posttest axial temperature, F(2, 223) = 14.9, p < .0001. The 1 mg/kg dose group’s mean of 33.8 ± 1.1°C and the 3 mg/kg dose group’s mean of 33.2 ± .7°C were both lower than the vehicle group’s mean of 34.3 ± .9°C (p < .01 for both, Dunnett’s post hoc test). The D1 antagonist also reduced axial temperature, F(2, 205) = 3.5, p = .031, which was due to the effect in the high (1.5 mg/kg) dose group. The Dunnett’s post hoc test, comparing each drug group to vehicle, revealed a significant difference (p < .05) only for the 1.5 mg/kg dose group. The means and standard errors were 33.6 ± 1.5°C for the 1.5 mg/kg dose group and 34.3 ± .8°C for the .3 mg/kg dose group.

Consistent with a prior report (Dastur et al., 1999), the D1 receptor agonist reduced locomotor activity, F(2, 240) = 12.2, p < .0001. The 1 mg/kg dose group’s mean locomotor activity score of 14.4 ± 1.0 and the 3mg/kg dose group’s mean of 16.1 ± 2.6 were significantly lower than the vehicle group’s mean of 23.3 ± 1.1 (Dunnett’s, p < .01 and p < .05, respectively). The D1 receptor antagonist reduced activity as well, F(2, 217) = 55, p < .0001. Both the .3mg/kg dose group’s mean of 3.9 ± 1.0 activity counts and 1.5 mg/kg dose group’s mean of 1.8 ± .4 were significantly lower than the vehicle group (Dunnett’s, p < .01 for both doses). Thus, reduction of locomotor activity can occur in the absence of effects on maternal potentiation. Moreover, opposite effects on isolation vocalization arise from the agonist and antagonist administrations, which both reduce locomotor activity.

There were no significant differences in amount of contact between dam and pup during reunion among the D1 receptor agonist dose groups and the vehicle group, F(3, 159) = .59, p = .62. Nor was there an effect of the D1 receptor antagonist on contact, F(2, 151) = .16, p = .85. So amount of dam contact cannot account for the drugs’ effects on vocalization.

Experiment 3: Test of Whether D1 and D2 Receptor Family Agonists’ Effects on Potentiation Require Activity of the Other Dopamine Receptor Family

Knowing that D1 receptor family and D2 receptor family agonists each reduce maternal potentiation, we asked does the effect of a dopamine receptor family selective agonist depend on activity of the other family’s receptor? Perhaps the D2 agonist’s capacity to disrupt potentiation depends on downstream activity of D1 receptors. Thus, the D2 receptor agonist was combined with the D1 receptor antagonist: 1 mg/kg quinpirole and .3 mg/kg SCH23390 (n = 32). The D1 receptor agonist was combined with the D2 receptor antagonist: 1 mg/kg SKF81297 and 1 mg/kg raclopride (D2 antagonist) (n = 22). These drug combinations were tested only in the dam-reunion condition. The effects of these groups were compared, as appropriate, to the effects of D1 and D2 receptor agonists by themselves, reported above. See Methods Section for further details.

We found that the D1 receptor antagonist did not prevent the D2 receptor agonist’s disruption of potentiation. Comparing the D2 agonist alone to the combination of the D2 agonist and D1 antagonist, the potentiation scores of the two groups (actually, the lack of potentiation) were not significantly different, F(1, 58) = .36, p = .55. The mean number of vocalizations (±SE) for the drug combination was 120 (±19.5) in ISO1 and the change score (ISO2–ISO1) was −6.6 (±18.4).

Similarly, in the presence of the D2 receptor antagonist, the D1 receptor agonist still reduced potentiation. The mean number of vocalizations (±SE) for the drug combination was 68 (±15.9) in ISO1 and the change score (ISO2–ISO1) was 30.6 (±12.5). The ANOVA of change score between the D1 agonist and the drug combination was not significant, F(1, 52) = .29, p = .59. These results demonstrate that the effect of one dopamine receptor family’s agonist on potentiation does not depend on activity of the other dopamine receptor family.

Experiment 4: Effect of Blocking Endogenous Dopamine Transmission Simultaneously at D1 and D2 Receptor Families on Isolation Vocalizations and Maternal Potentiation

As demonstrated with a D1 receptor antagonist in Experiment 2 and with a D2 receptor antagonist in previous work (Muller et al., 2005), selective antagonism of either D1 or D2 receptors has no selective effect on maternal potentiation of isolation vocalization. However the possibility remains that dam-contact induced changes of activity of either D1 or D2 receptors alone is sufficient to elicit potentiation. Thus, we tested this hypothesis by using systemic injections of both a dual D1 receptor family and D2 receptor family antagonist and a mixture of individual antagonists of each dopamine receptor family.

The dual D1 and D2 dopamine receptor family antagonist, alpha-flupenthixol, was tested at the following doses: .01 (n = 11), .1 (n = 32), .33 (n = 54), and 1 (n = 11) mg/kg. These dose groups were tested in the dam-reunion condition. A pickup control group was included for the .33 mg/kg dose (n = 11). To compare the dual antagonist effect to that of the combination of each dopamine receptor family-selective antagonist, another dam-reunion group was tested: .3 mg/kg SCH23390 and 1 mg/kg raclopride (n = 12). See Methods Section for further details.

Combined D1 and D2 Dopamine Receptor Family Antagonism Increased Isolation Vocalization and Disrupted Potentiation

The two highest doses of the combined D1 and D2 receptor family antagonist, alpha-flupenthixol reduced potentiation (see Fig. 6). The ANOVA of vocalization by isolation period and drug group for the dam-reunion condition showed a significant two-way interaction (F(4, 215) = 7.0, p < .0001). Post hoc testing showed potentiation scores for both the .33 mg/kg dose and the 1 mg/kg dose groups were significantly lower than vehicle, F(1, 164) = 21.4, p < .0001 and F(1, 121) = 12.24, p = .0007, respectively. In fact, at that highest dose, there was no significant difference between vocalization in initial isolation and that following dam reunion, t(10) = .11, p > .91. The .1 and .33 mg/kg doses showed potentiation and there was a trend toward potentiation in the .01 mg/kg dose group: .01 mg/kg group—t(10) = 2.0, p = .078; .1 mg/kg group—t(31) = 5.1, p < .0001; .33 mg/kg group—t(53) = 2.7, p = .0085. Comparisons between dam- reunion and pickup controls were available only for the .33 mg/ kg dose of flupenthixol. Although this dose reduced potentiation in the dam-reunion condition, in the pickup condition, the amount of vocalization in the second isolation period was not different than the amount of vocalization in the first isolation for that group (paired t(10) = .73, p = .48), or than the amount of vocalization in the first isolation for the .33 mg/kg flupenthixol group that would subsequently to show reduced potentiation after a dam reunion (t(63) = .42, p = .68). Thus, the pickup data suggest the drug’s effect on potentiation is not due to an interaction of the drug with aspects of the experimental design other than dam-contact.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of a combined D1- and D2-families antagonist on isolation vocalization and potentiation of isolation vocalization. (A) Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min initial isolation (ISO1). Injection with the dual antagonist, flupenthixol increased vocalization (** indicates p < .01). (B) Mean (±SE) difference in number of vocalizations between an initial isolation and a reisolation that followed 2 min “reunion” phase either with the anesthetized dam or a pickup condition (pup handling as in the dam-contact reunion, but without the dam) (ISO2–ISO1). Flupenthixol reduced potentiation at the .33 mg/kg dose and eliminated it at the 1 mg/kg dose. Asterisks indicate that a drug group is significantly different the dam-reunion vehicle group, ***p < .001. “+” indicates ISO2–ISO1 is significantly different than 0.

The same question of whether D1 and D2 receptor family antagonism disrupted potentiation was also addressed using a combination of selective D1 and D2 receptor family antagonists. Similar to the effect on potentiation of the 1 mg/kg dose of flupenthixol, among dam-reunion subjects, potentiation in the group with the combination of a .3 mg/kg dose of SCH23390 and a 1 mg/kg dose of raclopride (mean= −36 ± 15.8) was significantly lower than the vehicle group (mean = 92 ± 7.9), F(1, 122) = 27, p < .0001. In fact, in the combination of D1 and D2 receptor family antagonists group there was a reduction in vocalization in the isolation following dam reunion as compared to the initial isolation, t(11) = −2.33, p < .04.

To test whether the reduced maternal potentiation of isolation vocalizations following the combination of both D1 and D2 receptor antagonism was due to a ceiling effect on vocalization, we tested the ability of exposure to a cold environment to increase vocalization rate. In the 1 mg/kg dose of flupenthixol group that showed no potentiation, vocalization rate did increase substantially when tested in the cold, paired t(9) = 3.2, p = .012 (compare the 1 mg/kg D1 and D2 antagonist group’s ISO1 vocalization at room temperature data in Fig. 6 to its vocalization in the cold-environment test data in Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of a combined D1- and D2-families antagonist on isolation vocalizations in a cold environment (10°C). Mean (±SE) number of vocalizations during a 2-min isolation. There was no significant effect of drug on vocalizations in the cold. “ns” indicates not significantly different than vehicle.

In addition to its disruption of potentiation, flupenthixol enhanced isolation-induced vocalization. Among the dam-reunion groups, in the three-way ANOVA of vocalization by drug and testing period, the main effect of drug condition was significant (F(4, 215) = 3.5, p < .0088). Dunnett’s post hoc analysis showed the .33 mg/kg dose group was significantly higher than the vehicle group at the p < .01 level (see Fig. 6). The combination of individual D1 and D2 receptor family antagonists similarly elevated the initial vocalization rate (mean ± SE = 142 ± 26.3) compared to vehicle (mean = 71 ± 6.3), t(156) = 3.1, p = .0027. However flupenthixol’s enhancement of vocalization did not generalize to all circumstances. In the cold environment, there was no significant difference in amount of vocalization among the vehicle and .33 and 1.0 mg/kg flupenthixol groups, F(2, 53) = 1.7, p = .19 (see Fig. 7).

Combined D1 and D2 Receptor Family Antagonist Altered Nonvocalization Measures

Flupenthixol reduced body temperature. The 1 mg/kg dose of flupenthixol group had a mean (±SE) posttest axial temperature of 32.4 ± .5; the .33 mg/kg dose group’s mean was 33.9 ± .2; the .1 mg/ kg dose group’s mean was 33.9 ± .2; the .01 mg/kg dose group’s mean was 33.3 ± .6; and the vehicle group’s mean was 34.3 ± .07°C. The ANOVA of body temperature by dose was significant F(4, 257) = 8.9, p < .0001. Dunnett’s post hoc analysis showed that temperatures of the .01 and .33 mg/kg dose groups were significantly lower than the vehicle group at the p < .05 level; the 1 mg/kg dose group was significantly lower, at the p < .01 level.

There was no effect of the dose of flupenthixol on the amount of contact with the dam during the reunion phase of the behavioral procedure: time in contact with dam by drug condition, F(4, 216) = 1.6, p = .18. So, the drug’s effects on vocalization cannot be accounted for through a change in time in contact with the dam.

There was a significant effect of dose of flupenthixol on locomotor activity, F(4, 274) = 25.8, p < .0001 (see Fig. 8). A Dunnett’s post hoc analysis revealed the locomotor activity counts of the .1, .33, and 1 mg/kg dose groups were significantly lower than vehicle, all at the p < .01 level; the .01 mg/kg dose group was not significantly different than vehicle. Moreover, we observed a positive correlation between activity and potentiation among all the flupenthixol dose data, r = .31; F(1, 106) = 11.0, p = .0013. At the highest dose of flupenthixol and with the combination of individual D1 and D2 receptor family selective antagonists, both potentiation and locomotor activity were absent (see Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of D1- and D2-family dual antagonism on locomotor activity plotted against its effect on maternal potentiation. Mean (±SE) potentiation score on y-axis plotted against mean (±SE) locomotor activity score (counts of several behaviors summed over all observed behavior periods (see Methods Section)—a higher score represents more activity) on the x-axis. A linear regression line is plotted for the flupenthixol doses. For the highest dose of flupenthixol and the combination of individual D1 and D2 antagonists, the absence of locomotor activity suggests the doses may be sedating.

DISCUSSION

Potentiation of isolation-induced vocalization, a pup behavior elicited by the recent presence of a potential caregiver, offers an important behavioral paradigm to understand the neurobiology of motivated social behavior in the infant. Previously, we have shown that activation of the D2 receptor family systemically (Muller et al., 2005) and in the ventral striatum (Muller et al., 2008) disrupts the maternal potentiation of isolation-induced vocalization at a dose that does not alter vocalization rate in the initial isolation. Here further evidence from systemic pharmacological manipulations of dopamine receptors adds to our knowledge of the role of dopamine in this infant social behavior. The previous conclusion that activation of D2 receptors disrupts maternal potentiation is supported here by demonstrating that the D2 agonist’s effect over the repeated testing design in the absence of dam-contact cannot explain the drug’s disruption of potentiation following dam-contact. Although D1 receptor activation also disrupts potentiation, it does so by use of a D1 agonist dose that also dramatically reduces vocalizations in the initial isolation, in the cold environment, and in the re-isolation of pickup controls. Since the D1 antagonist combined with the D2 agonist does not alter the effect of the D2 agonist on potentiation and similarly the D2 antagonist does not alter the D1 agonist’s effect on potentiation, neither the D1 nor the D2 agonist’s reduction of potentiation is dependent on activity of the other dopamine receptor family. Finally, combined antagonism of both D1 and D2 receptor families disrupts maternal potentiation, but at a dose that also blocks locomotion.

In the results of Experiment 1, there were two trends toward quinpirole reducing vocalizations that were unrelated to dam-contact, but these effects cannot account for quinpirole’s disruption of maternal potentiation. In pickup controls (handled, but not exposed to dam-contact) the number of vocalizations in the second isolation was slightly lower than in the first isolation. In addition, the number of vocalizations in a cold (10°C) environment tended to be lower in the 1 mg/kg dose of quinpirole group than in the vehicle group. However, we previously reported that a 3 mg/kg systemic dose of quinpirole had a mean vocalization rate of greater than 250 in 2 min in cold test identical to that done here (Muller et al., 2005), suggesting the lower rate in the 1 mg/kg group here may have arisen by chance variation. In any case, the current results raise the possibility that the absence of an increase from ISO1 to ISO2 in the quinpirole dam-reunion group could be due, not to dam contact, but to the underlying reduction of vocalization caused by quinpirole over the time course of the experiment. However, this cannot explain the drug’s block of potentiation. If such a time course effect of quinpirole did account for the absence of potentiation in the quinpirole dam-reunion group, then the three-way interaction would not have been significant. These results suggest that D2 receptor activation by the 1 mg/kg dose of quinpirole disrupts maternal potentiation of isolation vocalizations more potently than it affects other domains of infant isolation vocalizations.

In our previous work concerning the effect of systemic administration of a D2 agonist on isolation vocalizations, and specifically maternally potentiation of them (Muller et al., 2005), we discussed the differences of our D2 agonist results with those of another report (Dastur et al., 1999). We had seen a selective effect of the ligand on maternal potentiation; the other group, without studying the effect of recent dam-contact, reported a general effect of the same ligand on isolation vocalization. Now, perhaps we are able to better highlight how the differences in protocols might account for the different results. Using pickup controls in this study, we were able to observe a decline in vocalization over the total 6 min of testing, that was not present in the initial 2 min isolation we had used in the previous article to address the question of the general effect of quinpirole on the rate of isolation vocalizations. Thus we too observe a reduction in isolation vocalizations from quinpirole. This decline, however, is unable to account for the larger effect of quinpirole in disrupting maternal potentiation. Our results, using either method (first 2 min or all 6 min of pickup data) agree with the Dastur article that D1 agonists reduce isolation vocalizations.

Combined antagonism of both D1 and D2 receptors blocked maternal potentiation. The dual antagonist also enhanced isolation vocalizations, but the increased baseline vocalization did not introduce a ceiling effect that would explain the absence of potentiation: vocalization rate could and did increase when subjects were isolated in a cold environment. At doses that disrupted potentiation, antagonism of both D1 and D2 receptors also eliminated motor activity. If absence of locomotion indicates sedation, it could be the case that the effect of flupenthixol in blocking potentiation was due to its reducing arousal. However if potentiation of vocalization requires a degree of arousal absent in the high dose of flupenthixol, isolation-induced vocalization itself clearly does not. Flupenthixol increased isolation-induced vocalizations, even at its highest, putatively sedating dose. Whether the disruption of potentiation is due to a reduction in arousal or a more specific effect on circuits underlying maternal-potentiation behavior needs further investigation.

The D1 agonist and the combined D1 and D2 receptor family antagonist reduced body temperature while also reducing or completely blocking maternal potentiation, respectively. However, the drugs’ effects on temperature cannot account for the effects on potentiation. Although both conditions reduced body temperature, vocalizations failed to increase—the opposite of what would be expected by lowered body temperature. Further, there was an example in the second experiment of a dissociation between temperature and potentiation of vocalization that suggests the two are not necessarily always causally linked. Both the D1 agonist and D1 antagonist reduced temperature but had opposite effects on vocalization. Finally, temperature reductions of the magnitudes reported here have not been associated previously with changes in potentiation (Farrell & Alberts, 2000; Kraebel, Brasser, Campbell, Spear, & Spear, 2002; Shair et al., 2003).

Although not a unique phenomenon, one of the most striking findings of the role of dopamine in infant isolation vocalizations is that systemically administered dopamine agonists reduce and antagonists increase the behavior. Indeed, we believe our finding that the D1 receptor family antagonist SCH23390 and the combined D1 and D2 receptor family antagonist flupenthixol increase isolation vocalization are the first evidence that implicate endogenous D1 activity in the suppression of isolation vocalization rate. Typically (but not exclusively), the effects of dopamine on motivated behavior are the reverse, and in fact here too the opposite is observed for locomotor activity: agonists increase and antagonists decrease locomotor activity. Whether these results can be understood as distinguishing dopamine’s role in recently acquired instrumental behavior from habitual behaviors (Wickens, Horvitz, Costa, & Killcross, 2007) or some as yet unknown explanation remains to be determined.

Towards a Model of the Social Mediation of Infant Vocalization Responses to Isolation

Here and in the companion article (Shair et al., in press) we studied the role of dopamine in the social mediation of differences in the rate of isolation-induced vocalization: dam-induced contact quieting, littermate-induced contact quieting, and maternal potentiation of isolation vocalization. There is behavioral and now pharmacological evidence that these three forms of social modulation of isolation vocalization are not causally linked. First, maternal potentiation of vocalization can occur in pups that have never experienced full social isolation (Hofer, Brunelli, & Shair, 1993) nor significant contact quieting prior to re-separation from dam (Shair et al., 2003). That is, for the latter point, contact with the dam or another adult female is necessary to produce vocal potentiation, but a significant reduction in vocalization rate during that contact is not. Secondly, although pups show contact quieting to both littermates and adults, the companion article demonstrates that dam contact quieting is dependent on dopamine, but littermate contact quieting is dramatically less so. We postulate that distinct neuromodulatory processes underlying each of these three social phenomena act on a neural circuit that mediates isolation vocalization.

To understand the social modulation of isolation-induced vocalizations, it is important to consider the neural basis of the vocalizations themselves. Reviews of brain regions involved in vocalization (Jurgens, 2002) and mammalian “cries” in particular (Newman, 2007), identify a substantial portion of the central nervous system from spinal cord to forebrain. To date relatively few studies have examined the neuroanatomy of infant cries. Infant ultrasonic isolation vocalizations can be produced in rat pups in which the forebrain has been disconnected by knife cut, but the rate of vocalization is virtually eliminated during the duration of isolations commonly studied (Middlemis-Brown, Johnson, & Blumberg, 2005). Lesions of the ventrolateral periacque-ductal gray of 10-day-old rat pups reduced isolation-induced vocalization during 10 min isolations by 80% (Wiedenmayer, Goodwin, & Barr, 2000). We have recently found that inactivation of the nucleus accumbens blocks isolation vocalization by rat pups in the first 2 min of isolation, both at room temperature and in a cold environment (Muller, Shair, Moore, manuscript). Local infusion of a substance P antagonist in the basolateral amygdala attenuates audible isolation vocalizations in infant guinea pigs (Boyce et al., 2001). Future neuroanatomical findings are likely as there is an extensive literature of the effects of systemic drug administration on infant isolation vocalization (for a review see Brunelli & Hofer, 2001). Notably anxiolytics reduce and anxiogenics increase infant isolation vocalization, suggesting an affective component and explaining why isolation-induced vocalization is often considered a reflection of a distress-like internal state. It is also well known that both the temperature of the pup and its environment play an important role in rate of isolation vocalization (Blumberg, 1992, #1364).

Contact quieting, on the other hand, is often thought to be a comfort response to termination of isolation by socially relevant stimuli. The more similar to a familiar social companion(s) a stimulus is, the more effectively it induces comfort quieting (Hofer & Shair, 1980). Pups nose and burrow against the companion(s), sometimes attaching to teats in the case of the dam. Differences in the stimulus properties of, or the responses elicited by, distinct companions may involve different neurochemical processes that modulate vocalization. The companion article (Shair et al., in press) presents significant evidence that endogenous dopamine plays a critical role in dam contact quieting, but not so for littermate contact quieting. Both D1 and D2 receptor-family antagonists disrupted dam-induced contact quieting, but had no (D1) or a lesser (D2) effect on littermate-induced contact quieting. There is evidence that endogenous opioids may play a comparable role for littermate companions (Carden & Hofer, 1990) but not all results support that possibility (Winslow & Insel, 1991).

Sensory modalities and neural circuitry responsible for contact quieting remain to be identified. We do know that both tactile and olfactory cues are important for the pup (Hofer, 1996). Where these signals are integrated, and where dopamine plays a role in dam-induced quieting is not known. As shown in the companion article (Shair et al., in press), neither antagonism of D2 receptors in the ventral striatum nor the dorsal striatum appears to be sufficient to disrupt dam-induced contact quieting.

It remains to be understood why dopamine is implicated in dam, but not littermate-induced contact quieting. Our preliminary hypothesis is that dam contact quieting depends on the dam’s reinforcement properties that recruit and depend on dopamine. It is known that the dam acts as a positive reinforcer for pup behavior (Amsel, Radek, Graham, & Letz, 1977), but whether littermates can reinforce pup behavior has not been studied. Although both dam and littermates can provide some degree of warmth, only the dam can provide food and act to protect the pup against predators and other environmental threats. Dopamine does play an important role in feeding behavior (Baldo, Kelley, Baldo, & Kelley, 2007). During the first days of life, pups may learn that the dam is rewarding, or that littermates are not, or that their reward properties differ. An alternative is that one or more forms of contact are innately quieting and each uses different neural substrates, including differential dependence on dopamine. Studies of dam contact quieting after artificial rearing without dam exposure as well as measuring dopamine during contact with different classes of companions throughout ontogeny could add to our understanding of the neural basis of this early life comfort response.

Maternal potentiation might be understood from an evolutionary perspective, as an adaptation to a critical survival conflict faced by an isolated pup. There is advantage in recruiting retrieval by a caregiver; on the other hand, to do so by vocalizing risks detection by predators. A simple strategy would be to vocalize more when there is a higher probability of the vocalization leading to a positive outcome. Support for this view has been found in primates. An isolated infant squirrel monkey vocalizes more when it sees its mother than when the mother is completely absent (Wiener, Bayart, Faull, & Levine, 1990). Further, rat pups raised without exposure to adult males cease vocalization in isolation when exposed to the smell of a (potentially predatory) adult male rat (Brunelli et al., 1998). What is the role of dopamine in maternal potentiation? It is clear that dopamine receptor activation must be at a low level, particularly in the ventral striatum, to permit maternal potentiation of isolation-induced vocalization (Muller et al., 2005, 2008). One model for maternal potentiation, therefore, is that a nondopaminergic circuit is involved in registering the dam’s prior presence and current absence, leading to increased vocalization during isolation. Although the substrate for registering the dam’s presence and subsequent removal is yet unidentified, its output would be inhibited by D2 receptor activation in the ventral striatum An alternative hypothesis is based on the work of Schultz and colleagues exploring the role of dopamine, expectancy, and reward. Transient changes in dopamine could be elicited by the dam’s unexpected presentation in the reunion phase and the dam’s unexpected removal in the subsequent reisolation, as Schultz has observed regarding presentations and unexpected absences of food rewards (Schultz, 2007). A transient drop in dopamine levels following the dam’s removal could remove dopamine’s tonic inhibition of isolation vocalization rate and hence be the mechanism of the maternal potentiation of isolation-induced vocalizations. The idea that endogenous dopamine levels tonically inhibit isolation vocalization rate is supported by our findings here that systemic administration of either the D1 receptor antagonist or the dual D1 and D2 antagonist increase isolation vocalization. It might appear we have already disproved that endogenous dopamine levels play a role in maternal potentiation of isolation vocalizations by showing that neither systemic D1 nor D2 antagonists alone disrupt potentiation, however, we did find that the combination of D1 and D2 receptor antagonism did block potentiation. We could not rule out the possibility that the dual antagonist’s block of potentiation arose from a nonspecific effect on arousal. The hypothesis could be tested by blocking both D1 and D2 receptors only in the ventral striatum to see if that would disrupt potentiation without sedation.

In conclusion, here we have shown that systemic D2 receptor family activation disrupts the maternal potentiation of isolation induced vocalization in a manner that is more selective than D1 receptor family activation, which reduces other measures of isolation vocalizations at a dose that blocks potentiation. The combined D1 and D2 receptor family antagonist’s systemic administration disrupts maternal potentiation. Further work is needed to understand the neural mechanisms responsible for these findings. Extending work in other labs that established dopamine is critical for adult social behaviors (Aragona, Liu, Curtis, Stephan, & Wang, 2003; Stern & Lonstein, 2001), our previous work (Muller et al., 2005, 2008) and the results of the experiments here show that dopamine can play a critical role in the expression of an infant social behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants MH018264, MH66171, and T32 DA016224 (JMM), the Lieber Schizophrenia Research Center at Columbia University, and the New York State Office of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- Amsel A, Radek CC, Graham M, Letz R. Ultrasound emission in infant rats as an indicant of arousal during appetitive learning and extinction. Science. 1977;197(4305):786–788. doi: 10.1126/science.560717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Curtis JT, Stephan FK, Wang Z. A critical role for nucleus accumbens dopamine in partner-preference formation in male prairie voles. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(8):3483–3490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03483.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Kelley AE. Discrete neurochemical coding of distinguishable motivational processes: Insights from nucleus accumbens control of feeding. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):439–459. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer LE, Brown A, Mactutus CF, Booze RM, Strupp BJ. Prenatal cocaine exposure increases sensitivity to the attentional effects of the dopamine D1 agonist SKF81297. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(23):8902–8908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08902.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg MS, Efimova IV, Alberts JR. Ultrasonic vocalizations by rat pups: The primary importance of ambient temperature and the thermal significance of contact comfort. Developmental Psychobiology. 1992;25(4):229–250. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce S, Smith D, Carlson E, Hewson L, Rigby M, O’Donnell R, et al. Intra-amygdala injection of the substance P [NK(1) receptor] antagonist L-760735 inhibits neonatal vocalisations in guinea-pigs. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(1):130–137. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli SA, Hofer MA. Selective breeding for an infantile phenotype (isolation calling): A window on developmental forces. In: Blass EM, editor. Developmental Psychobiology. Vol. 13. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 433–482. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli SA, Keating CC, Hamilton NA, Hofer MA. Development of ultrasonic vocalization responses in genetically heterogeneous National Institute of Health (N:NIH) rats. I. Influence of age, testing experience, and associated factors. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;29(6):507–516. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199609)29:6<507::AID-DEV3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli SA, Masmela JR, Shair HN, Hofer MA. Effects of biparental rearing on ultrasonic vocalization (USV) responses of rat pups (Rattus norvegicus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1998;112(4):331–343. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli SA, Vinocur DD, Soo-Hoo D, Hofer MA. Five generations of selective breeding for ultrasonic vocalization (USV) responses in N:NIH strain rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;31(4):255–265. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199712)31:4<255::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales JJ, Iversen SD. Dynamic dopamine receptor interactions in the core and shell of nucleus accumbens differentially coordinate the expression of unconditioned motor behaviors. Synapse. 2000;36(4):297–306. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(20000615)36:4<297::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carden SE, Hofer MA. Socially mediated reduction of isolation distress in rat pups is blocked by naltrexone but not by Ro 15-1788. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1990;104(3):457–463. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastur FN, McGregor IS, Brown RE. Dopaminergic modulation of rat pup ultrasonic vocalizations. European Journal of Pharmacolology. 1999;382(2):53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00590-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, Smith J, Mirenowicz J. Dissociation of Pavlovian and instrumental incentive learning under dopamine antagonists. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114(3):468–483. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MJ, Futter D, Bonardi C, Killcross S. Attenuation of d-amphetamine-induced disruption of conditional discrimination performance by alpha-flupenthixol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177(3):296–306. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell WJ, Alberts JR. Ultrasonic vocalizations by rat pups after adrenergic manipulations of brown fat metabolism. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114(4):805–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA. Multiple regulators of ultrasonic vocalization in the infant rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21(2):203–217. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Brunelli SA, Shair HN. Ultrasonic vocalization responses of rat pups to acute separation and contact comfort do not depend on maternal thermal cues. Developmental Psychobiology. 1993;26(2):81–95. doi: 10.1002/dev.420260202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Brunelli SA, Shair HN. Potentiation of isolation-induced vocalization by brief exposure of rat pups to maternal cues. Developmental Psychobiology. 1994;27(8):503–517. doi: 10.1002/dev.420270804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Shair H. Sensory processes in the control of isolation-induced ultrasonic vocalization by 2-week-old rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1980;94(2):271–279. doi: 10.1037/h0077665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Shair HN. Ultrasonic vocalization during social interaction and isolation in 2-week-old rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1978;11(5):495–504. doi: 10.1002/dev.420110513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo A, Wiedholz LM, Millstein RA, Yang RJ, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, et al. Genetic and dopaminergic modulation of reversal learning in a touchscreen-based operant procedure for mice. Behavioral Brain Research. 2006;171(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens U. Neural pathways underlying vocal control. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reveiws. 2002;26(2):235–258. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe P, Boylan CB. Cocaine-induced effects on isolation stress in neonatal rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1992;106(2):374–379. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraebel KS, Brasser SM, Campbell JO, Spear LP, Spear NE. Developmental differences in temporal patterns and potentiation of isolation-induced ultrasonic vocalizations: Influence of temperature variables. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;40(2):147–159. doi: 10.1002/dev.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall SA, Crawford CA, Nonneman AJ. Reinforced responding of the 11-day-old rat pup: Synergistic interaction of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1992;42(1):163–168. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90460-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlemis-Brown JE, Johnson ED, Blumberg MS. Separable brainstem and forebrain contributions to ultrasonic vocalizations in infant rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(4):1111–1117. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.4.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moles A, Kieffer BL, D’Amato FR. Deficit in attachment behavior in mice lacking the mu-opioid receptor gene. Science. 2004;304(5679):1983–1986. doi: 10.1126/science.1095943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JM, Brunelli SA, Moore H, Myers MM, Shair HN. Maternally modulated infant separation responses are regulated by D2-family dopamine receptors. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(5):1384–1388. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JM, Moore H, Myers MM, Shair HN. Ventral striatum dopamine D2 receptor activity inhibits rat pups’ vocalization response to loss of maternal contact. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122(1):119–128. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JD. Neural circuits underlying crying and cry responding in mammals. Behavioral Brain Research. 2007;182(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GD, Howes SR, Whitelaw RB, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Analysis of the effects of intra-accumbens SKF-38393 and LY-171555 upon the behavioural satiety sequence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;117(1):82–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02245102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, McBride WJ. D1-D2 dopamine receptor interaction within the nucleus accumbens mediates long-loop negative feedback to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;77(5):1248–1255. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Behavioral dopamine signals. Trends in Neurosciences. 2007;30(5):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shair HN. Acquisition and expression of a socially mediated separation response. Behavioral Brain Research. 2007;182(2):180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shair HN, Brunelli SA, Masmela JR, Boone E, Hofer MA. Social, thermal, and temporal influences on isolation-induced and maternally potentiated ultrasonic vocalizations of rat pups. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;42(2):206–222. doi: 10.1002/dev.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shair HN, Muller JM, Moore H. Dopamine’s role in social modulation of infant isolation-induced vocalization: I. Reunion responses to the dam, but not littermates, are dopamine dependent. Developmental Psychobiology. doi: 10.1002/dev.20353. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Sales DG. Ultrasonic behavior and mother-infant interactions in rodents. In: Bell RW, Smotherman WP, editors. Maternal Influences and Early Behavior. New York: Spectrum Publications; 1980. pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Stern JM, Lonstein JS. Neural mediation of nursing and related maternal behaviors. Progress in Brain Research. 2001;133:263–278. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)33020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczypka MS, Zhou QY, Palmiter RD. Dopamine-stimulated sexual behavior is testosterone dependent in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112(5):1229–1235. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley MR, Rebec GV, Timberlake W. Facilitation of efficient search of an unbaited radial-arm maze in rats by D1, but not D2, dopamine receptors. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2001;70(2–3):181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters JR, Bergstrom DA, Carlson JH, Chase TN, Braun AR. D1 dopamine receptor activation required for postsynaptic expression of D2 agonist effects. Science. 1987;236(4802):719–722. doi: 10.1126/science.2953072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Yu G, Cascio C, Liu Y, Gingrich B, Insel TR. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated regulation of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): A mechanism for pair bonding? Behavioral Neuroscience. 1999;113(3):602–611. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens JR, Horvitz JC, Costa RM, Killcross S. Dopaminergic mechanisms in actions and habits. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(31):8181–8183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenmayer CP, Goodwin GA, Barr GA. The effect of periaqueductal gray lesions on responses to age-specific threats in infant rats. Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research. 2000;120(2):191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener SG, Bayart F, Faull KF, Levine S. Behavioral and physiological responses to maternal separation in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) Behavioral Neuroscience. 1990;104(1):108–115. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Insel TR. Endogenous opioids: Do they modulate the rat pup’s response to social isolation? Behavioral Neuroscience. 1991;105(2):253–263. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]