Abstract

Background In studies of all-cause mortality, the fundamental epidemiological concepts of rate and risk are connected through a well-defined one-to-one relation. An important consequence of this relation is that regression models such as the proportional hazards model that are defined through the hazard (the rate) immediately dictate how the covariates relate to the survival function (the risk).

Methods This introductory paper reviews the concepts of rate and risk and their one-to-one relation in all-cause mortality studies and introduces the analogous concepts of rate and risk in the context of competing risks, the cause-specific hazard and the cause-specific cumulative incidence function.

Results The key feature of competing risks is that the one-to-one correspondence between cause-specific hazard and cumulative incidence, between rate and risk, is lost. This fact has two important implications. First, the naïve Kaplan–Meier that takes the competing events as censored observations, is biased. Secondly, the way in which covariates are associated with the cause-specific hazards may not coincide with the way these covariates are associated with the cumulative incidence. An example with relapse and non-relapse mortality as competing risks in a stem cell transplantation study is used for illustration.

Conclusion The two implications of the loss of one-to-one correspondence between cause-specific hazard and cumulative incidence should be kept in mind when deciding on how to make inference in a competing risks situation.

Keywords: Censored data, competing risks, regression models, survival analysis

Introduction

Epidemiology deals with the occurrence of diseases in populations when observed over time, and the frequency with which diseased cases occur is measured using the concepts of ‘risk’ and ‘rate’. Standard text books in epidemiology (e.g. Rothman,1 Ch. 3; dos Santos Silva,2 Section 4.2) typically define the risk as the fraction  of N originally disease-free individuals in the population who develop the disease over a specified follow-up period, say, from time 0 to time t. Note that the risk must necessarily increase with t. On the other hand, the rate would typically be defined as the number, D, of individuals in the population who develop the disease during a specified follow-up period (from 0 to t) divided by the amount of person-time at risk, Y, observed when following disease-free individuals from the population from 0 to t. The rate

of N originally disease-free individuals in the population who develop the disease over a specified follow-up period, say, from time 0 to time t. Note that the risk must necessarily increase with t. On the other hand, the rate would typically be defined as the number, D, of individuals in the population who develop the disease during a specified follow-up period (from 0 to t) divided by the amount of person-time at risk, Y, observed when following disease-free individuals from the population from 0 to t. The rate  may increase, stay roughly constant, or decrease when varying the length t of the follow-up period.

may increase, stay roughly constant, or decrease when varying the length t of the follow-up period.

The statistical counterpart of a risk is a ‘probability’. Thus, if F(t) denotes the probability that a randomly selected disease-free individual gets the disease before time t then the risk  estimates F(t) if all N disease-free individuals in the population are followed from 0 to t. However, in most follow-up studies there will inevitably be loss to follow-up, ‘censoring’, and F(t) must then be estimated using more complicated techniques able to account for censoring.

estimates F(t) if all N disease-free individuals in the population are followed from 0 to t. However, in most follow-up studies there will inevitably be loss to follow-up, ‘censoring’, and F(t) must then be estimated using more complicated techniques able to account for censoring.

The statistical discipline that deals with censored follow-up data is ‘survival analysis’ and in the next paragraphs we will summarize basic (perhaps well-known) features of survival analysis. We will do that in the context where the event under study (‘the disease’) is all-cause mortality, that is, an event which will occur with probability one if the follow-up period is sufficiently long (t is ‘large’). However, our motivation for doing this is to set the scene for the situation where observation of the disease under study may be preceded by other events, the occurrence of which prevents us from observing the disease of interest. This ‘competing risks’ situation (which is the rule rather than the exception in epidemiological follow-up studies) is the topic for the present article. We shall discuss which concepts from classical survival analysis (i.e. studies of all-cause mortality) immediately extend to competing risks and we shall discuss when to be more careful.

Survival analysis

In survival analysis, the object is the time elapsed from an initiating event, e.g. the onset of some disease, to death. The probability F(t) of dying before time t, the cumulative distribution function, is in some epidemiological texts, e.g. Olsen et al.,3 p. 3 and Rothman and Greenland,4 p. 37, denoted the ‘cumulative incidence function’, and if time to death was observed for every one in the sample then, as explained above, F(t) can be estimated as the relative frequency of survival times less than t. However, the challenge is to estimate F(t) based on incomplete data, i.e. to make inference on the underlying, potentially completely observed population in the presence of censored observations. For this to be feasible, censoring must be ‘independent’, that is, an individual censored at time t should be representative for those still at risk at that time. In other words, those censored should not be individuals with systematically high or low risk of dying. Under independent censoring, F(t) may be estimated by  , where

, where  is the ‘Kaplan–Meier estimator’ for the probability S(t) = 1 − F(t) of surviving time t. The Kaplan–Meier estimator at time t is a product with a factor for each failure time before t. The factor at failure time s is

is the ‘Kaplan–Meier estimator’ for the probability S(t) = 1 − F(t) of surviving time t. The Kaplan–Meier estimator at time t is a product with a factor for each failure time before t. The factor at failure time s is  where Ds is the number of failures observed at s (often Ds = 1), and Ns the number of individuals in the study still ‘at risk’, i.e. alive and uncensored, at time s. We illustrate this calculation in a small set of data in Table 1.

where Ds is the number of failures observed at s (often Ds = 1), and Ns the number of individuals in the study still ‘at risk’, i.e. alive and uncensored, at time s. We illustrate this calculation in a small set of data in Table 1.

Table 1.

Illustration of estimates of the survival function  , the overall cumulative hazard

, the overall cumulative hazard  , cause-specific cumulative hazards

, cause-specific cumulative hazards  and cause-specific cumulative incidences

and cause-specific cumulative incidences  based on a small set of censored survival data with 2 competing events

based on a small set of censored survival data with 2 competing events

| s | Ds | Cause | Ns |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | – | – | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 0.917 | 0.083 | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.000 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0.917 | 0.083 | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.000 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0.825 | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.000 | 0.175 | 0.000 |

| 8 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 0.733 | 0.294 | 0.183 | 0.111 | 0.175 | 0.092 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0.733 | 0.294 | 0.183 | 0.111 | 0.175 | 0.092 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.733 | 0.294 | 0.183 | 0.111 | 0.175 | 0.092 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0.611 | 0.461 | 0.350 | 0.111 | 0.297 | 0.214 |

| 15 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0.489 | 0.661 | 0.350 | 0.311 | 0.297 | 0.214 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.367 | 0.911 | 0.600 | 0.311 | 0.419 | 0.214 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.367 | 0.911 | 0.600 | 0.311 | 0.419 | 0.214 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.367 | 0.911 | 0.600 | 0.311 | 0.419 | 0.214 |

| 23 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.911 | 0.600 | 1.311 | 0.419 | 0.581 |

s denotes the times of observation, Ds is the number of failures observed at s, cause is the corresponding cause (defined as 0 for the censored observations) and Ns is the number of subjects still at risk just before s. The Kaplan–Meier estimator  multiplies factors

multiplies factors  for previous times of observations (e.g.

for previous times of observations (e.g.  , the Nelson–Aalen estimator add terms

, the Nelson–Aalen estimator add terms  for previous times of observation (e.g.

for previous times of observation (e.g.  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  (and

(and  ) add terms

) add terms  for previous times of observation corresponding to failures from the given cause (e.g.

for previous times of observation corresponding to failures from the given cause (e.g.  ). Finally

). Finally  (and

(and  ) estimate the cumulative incidences using Equation (2) based on the columns

) estimate the cumulative incidences using Equation (2) based on the columns  and Ns (and cause) (e.g.

and Ns (and cause) (e.g.  ). Here,

). Here,  is used in the time point just before s. Note that, for all times s,

is used in the time point just before s. Note that, for all times s,  and

and  .

.

The concept in survival analysis that corresponds to the rate is the hazard function h(t). This has the interpretation that for a small interval from time t to time t + d, h(t) · d is approximately the conditional probability of death before time t + d given survival until time t. Thus, the hazard function provides a dynamic (‘local in time’) description of how the instantaneous risk of failing varies. The epidemiological rate  mentioned above is then a sensible estimate for the hazard function if this is roughly time-constant, i.e. when h(t) = h then

mentioned above is then a sensible estimate for the hazard function if this is roughly time-constant, i.e. when h(t) = h then  estimates h.

estimates h.

In survival analysis, there is a simple ‘one-to-one’ correspondence between the hazard function and the survival function. This relationship is

| (1) |

see e.g. Clayton and Hills.5 Here, H(t) is the cumulative hazard function at time t, that is, the hazard function h(·) added (or, mathematically more precise, ‘integrated’) over the time interval from 0 to t. It follows that, for given hazard function h(t), one may compute the survival function S(t) (or the cumulative incidence function F(t)), and vice versa: for given cumulative incidence the hazard may be computed. Under independent censoring, the cumulative hazard at time t may be estimated by the ‘Nelson–Aalen estimator’,  . This is a sum with a term for each failure time before t, the term at failure time s being

. This is a sum with a term for each failure time before t, the term at failure time s being  , a computation which is also illustrated in Table 1. Though values of the cumulative hazard do not have a simple interpretation, the Nelson–Aalen estimator is still useful since the slope of the curve is an estimate of the hazard. Note how the ‘one-to-one correspondence’ between rate and risk is reflected in the Kaplan–Meier and Nelson–Aalen estimators, which are both based on the same basic pieces of information: the number of failures, Ds and the number at risk, Ns at each failure time, s.

, a computation which is also illustrated in Table 1. Though values of the cumulative hazard do not have a simple interpretation, the Nelson–Aalen estimator is still useful since the slope of the curve is an estimate of the hazard. Note how the ‘one-to-one correspondence’ between rate and risk is reflected in the Kaplan–Meier and Nelson–Aalen estimators, which are both based on the same basic pieces of information: the number of failures, Ds and the number at risk, Ns at each failure time, s.

This has important consequences for the analysis of survival data because models for the hazard function, e.g. the Cox regression model6 which is very frequently used, immediately imply models for the cumulative incidence F(t). Thus, if a Cox regression model is fitted for the hazard function and if, based on this Cox model, presence of a certain factor is seen to be associated with a higher hazard function then presence of the factor is also associated with a higher cumulative incidence. The interpretation of the parameter estimated in a Cox regression model is a hazard ratio.

Example

For illustration, we use data of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). The data consist of all chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) patients, having received an allogeneic stem cell transplantation from an Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-identical sibling or a matched unrelated donor during the years 1997–2000. Patients had to be Philadelphia chromosome positive, transplanted with bone marrow or peripheral blood, and ≥18 years of age, leaving 3982 patients. Median follow-up was 8.5 years. An important and very predictive risk score is the EBMT risk score by Gratwohl et al.,7 originally taking values 0 through 7, and often (also here) for convenience grouped into five distinct groups, with EBMT risk score 0, 1 (n = 506), 2 (n = 1159), 3 (n = 1218), 4 (n = 745) and 5, 6, 7 (n = 354). Failure from transplantation may either be due to relapse, or to non-relapse mortality (NRM). Often these two endpoints are taken together to define what is called relapse-free survival (RFS), which is the time from transplantation to either relapse or death, whichever comes first. Table 2 shows counts and observed percentages of these events in each of the EBMT risk groups. The censored patients were alive without relapse at the end of their follow-up.

Table 2.

Number of censored observations and number of events for relapse and NRM in each of the EBMT risk groups

| EBMT risk group | Total | Relapse n(%) | NRM n(%) | Censored n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0,1 | 506 | 113 (22.3) | 94 (18.6) | 299 (59.1) |

| 2 | 1159 | 247 (21.3) | 323 (27.9) | 589 (50.8) |

| 3 | 1218 | 292 (24.0) | 404 (33.2) | 522 (42.9) |

| 4 | 745 | 193 (25.9) | 300 (40.3) | 252 (33.8) |

| 5,6,7 | 354 | 112 (31.6) | 169 (47.7) | 73 (20.6) |

Figure 1 shows both the Nelson–Aalen estimates of the cumulative hazards (A) and the Kaplan–Meier estimates of the survival curves (B) for RFS for each of the five risk groups.

Figure 1.

Nelson–Aalen estimates of the cumulative hazards (A) and the Kaplan–Meier estimates of the survival curves (B) for RFS for each of the five EBMT risk groups

Cox regression for RFS gives hazard ratios (HR) [95% confidence intervals (CIs)] of 1.27 (1.08–1.48), 1.61 (1.38–1.88), 2.08 (1.77–2.45) and 3.26 (2.73–3.91) of EBMT risk groups 2, 3, 4 and 5/6/7, respectively, with respect to the reference risk group of 0/1. Clearly, higher EBMT risk scores imply higher rates of the composite endpoint relapse or death, consistent with the left panel of Figure 1. Note that, due to the one-to-one correspondence between rate and risk, higher EBMT score also implies higher risk of relapse or death, i.e. lower RFS curves.

In conclusion, survival data (all-cause mortality data) may be characterized either by the ‘global parameter’, the cumulative incidence function F(t) or by the ‘local parameter’, the hazard function h(t). These two ways of characterization are equivalent due to their one-to-one correspondence.

Competing risks

Suppose now that the event of interest is the onset of a given disease but that, obviously, individuals may die without getting the disease. We may then be interested in the risk or probability of getting the disease in a given follow-up period from 0 to t or in the rate or hazard of getting the disease. A naïve analysis inspired by the methods for survival analysis outlined above could consider death without the disease as ‘independent censoring’, thereby aiming at making inference for an underlying, potentially completely observed population. However, that population would be one without ‘censoring’, that is, a purely hypothetical population where individuals could not die without the disease. A much more satisfactory approach, to be outlined in the following, is one where one acknowledges that individuals may die without the disease and where inference for disease risks and rates are made ‘in the presence of the competing risk of dying’.

Define F1(t) as the probability (cumulative incidence) of getting the disease before time t. Define, further, the ‘cause-specific hazard function’ for the disease, h1(t) as follows: h1(t) · d is (approximately, when d is small) the conditional probability of getting the disease before time t + d given that the individual is alive and disease-free up to time t. Now, in each little interval from t to t + d between time 0 and time t where the individual is still at risk (alive and disease-free), he or she has the possibilities of either getting the disease or dying (without having got it). Therefore, the cumulative incidence of getting the disease not only depends on h1(t) but also on the hazard of dying. This ‘cause-specific hazard of death’, h2(t) is defined similarly to h1(t); h2(t) · d is (approximately, when d is small) the conditional probability of dying before time t + d given that the individual is alive and disease-free up to time t. The consequence is that in the presence of the competing risk of death there is no longer a one-to-one correspondence between the (cause-specific) hazard (the rate h1(t)) and the probability (cumulative incidence) (the risk F1(t)) for the disease and in order to compute the cumulative incidence, the cause-specific hazard for the competing event is also needed. The relationship can be derived, as follows. Divide the interval from 0 to t into many small intervals each of length d. To get the disease before time t, it must occur in exactly one of these small intervals and the probability of getting the disease before time t, i.e. the cumulative incidence F1(t), is therefore the sum of the probabilities of getting the disease exactly in each little interval. The probability of getting the disease in the little interval from time s to time s + d is the probability of being alive and disease-free until time s times the conditional probability of getting the disease between s and s + d given alive and disease-free at s. The latter conditional probability is, by the definition of the cause-specific hazard (approximately) equal to h1(s) · d whereas the probability of being alive and disease-free (that is, the probability of staying event-free) until time s is (by an argument similar to that leading to Equation (1) for survival data) equal to S(s) = e−H1(s)−H2(s). Here H1(s) and H2(s) are the cumulative cause-specific hazards for the two competing events, disease and death without the disease. The result is that F1(t) is a sum of terms given by S(s) · h1(s) · d, where the sum is over all small intervals between 0 and t. Mathematically, this sum is the integral

| (2) |

Estimation of F1 (and F2) based on a small data set using this expression is illustrated in Table 1. Equation (2) shows that, via the factor S(s) which involves H2(s), the cumulative incidence for one failure cause (here: the disease) depends on the rate (cause-specific hazard) for the competing cause (here: death without the disease). This is the key feature of competing risks. There is no longer a one-to-one correspondence between cumulative incidence and cause-specific hazard (‘rate and risk’). This fact has two important implications:

a naïve estimator for the cumulative incidence F1(t) which only studies cause 1 events (disease cases), e.g. 1 minus the Kaplan–Meier estimator based only on disease events and treating deaths as independent censorings is (upwards) biased;

the way in which the cumulative incidence F1(t) is associated with covariates may not coincide with the way in which the cause-specific hazard h1(t) is associated with covariates, but will also depend on the association between covariates and the cause-specific hazard for the competing event h2(t).

Example

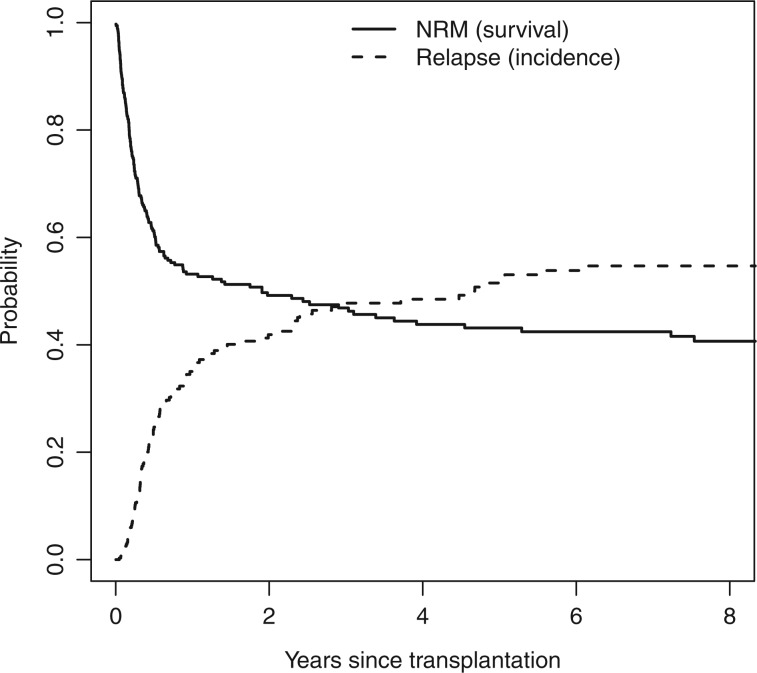

To illustrate the first point, consider the highest risk group, with EBMT risk score 5, 6 and 7. Figure 2 shows the naïve Kaplan–Meier estimates for relapse (censoring patients that died before relapse) and for NRM (censoring patients with relapse) for this highest risk group. The estimate of NRM is shown as a survival curve (starting at 1 and decreasing), the estimate of relapse as an incidence curve (starting at 0 and increasing).

Figure 2.

Naïve Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse and NRM, shown as incidence and survival curves, respectively

The estimated 5-year probabilities of relapse and NRM, obtained from these naïve Kaplan–Meiers, are 0.515 and 0.569, respectively. It is clear that these can never be unbiased estimates of the probabilities of relapse and NRM at 5 years, since they add up to more than 1. This is impossible, since relapse and NRM are mutually exclusive events. The correct estimates, using Equation (2) are shown in Figure 3. The previously obtained naïve Kaplan–Meier estimates are shown in grey.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence estimates of relapse and NRM, shown as incidence and survival curves, respectively; naïve Kaplan–Meier estimates are shown in grey

The estimated 5-year probabilities of relapse and NRM, obtained from this relation, are 0.316 and 0.475, respectively, and the 5-year RFS probability is 1 − 0.316 − 0.475 = 0.209, exactly as obtained in the previous section (Figure 1).

Next, we turn to the second point: the way covariates affect hazards may be different from the way they affect cumulative incidences. Figure 4 shows Nelson–Aalen estimates of the cumulative cause-specific hazards of relapse and NRM for each of the five EBMT risk groups.

Figure 4.

Nelson–Aalen estimates of the cumulative cause-specific hazards of (A) relapse and (B) NRM for each of the five EBMT risk groups

The overall picture is that higher EBMT risk score implies higher cause-specific hazards. This is particularly clear for NRM; the same is true in general for relapse, but the two lowest risk groups, those with risk scores 0, 1 and with risk score 2, are approximately equal. Table 3 shows the HRs and 95% CIs of the EBMT risk groups for relapse and NRM, obtained from two Cox proportional hazards models, one for relapse (censoring patients dying without relapse), the other for NRM (censoring patients with relapse).

Table 3.

Cause-specific hazard ratios and 95% CIs of the EBMT risk groups for relapse and NRM

| EBMT risk group | Relapse HR (95% CI) | NRM HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 0, 1 | ||

| 2 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 1.57 (1.25–1.97) |

| 3 | 1.28 (1.03–1.59) | 2.01 (1.61–2.52) |

| 4 | 1.57 (1.25–1.99) | 2.68 (2.12–3.37) |

| 5, 6, 7 | 2.67 (2.06–3.47) | 3.98 (3.09–5.13) |

Although, based on Figure 4, one could question the validity of the proportional hazards assumption, we see from Table 3 that the cumulative cause-specific hazards for relapse are quite similar for risk scores 0, 1 and for risk score 2. If anything, the risk group with score = 2 has slightly higher rate. Note that whereas, as argued above, the Kaplan–Meier estimator should not be used for ‘risk estimation’ in the presence of competing risks, we have used both the Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Cox regression model for the cause-specific ‘rates’. We will return to an explanation of this apparent paradox in the next section.

Based on these Cox models for the cause-specific hazards for relapse and NRM, we calculated, again using Equation (2), the model-based cumulative incidences for relapse and NRM for each of the EBMT risk groups. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Model-based cumulative incidence estimates for (A) relapse and (B) NRM for each of the five EBMT risk groups

Comparing these cumulative incidences of relapse for the two lowest risk groups, we notice a striking thing: the cumulative incidence of relapse is lower for the group with EBMT risk score 2, compared with the group with EBMT risk score 0, 1. Contrast this with what we saw earlier, namely that there is no difference in the cause-specific hazard of relapse between these two lowest risk groups (if anything, the rate for EBMT risk score 2 is higher). The example thus shows that the effect of EBMT risk score on the risk of relapse, the cumulative incidence, is different from its effect on the rate, the cause-specific hazard. The fact that the cumulative incidence of relapse is lower for the EBMT risk score 2 group, compared with the EBMT risk score 0, 1 group, even though the cause-specific hazard of relapse is (somewhat) higher, can be seen as follows. Ignoring true censorings for the moment, the ‘rate’, the cause-specific hazard of relapse, acts on those individuals still at risk, i.e. on those alive without relapse. The Cox model tells us that, at any point in time, this rate is higher for the EBMT risk score 2 group. But the cause-specific hazard of the competing event, NRM, is also higher for the EBMT risk score 2 group, compared with the EBMT risk score 0, 1 group, and the difference here is much larger. That means that over time, the risk set of the EBMT risk score 2 group decreases much more quickly than that of the EBMT risk score 0, 1 group. As a result, even though, relative to the size of the risk set, more individuals will have a relapse in the EBMT risk score 2 group, in absolute size there will in fact be fewer individuals with a relapse. Hence, the ‘risk’, the cumulative incidence of relapse, will be lower in the EBMT risk score 2 group.

Risk and rate models for competing risks

Recall the useful interpretation of the hazard rate in all-cause mortality studies from ‘Survival analysis’ section: h(t) is approximately the instantaneous risk per time unit of failure at time t given survival till just before t. Thereby, the parameters in the Cox regression model (see Example in that section) are hazard rate ratios. The interpretation carries over verbatim to the cause-specific hazard rate as introduced in ‘Competing risks’ section: h1(t) is approximately the ‘instantaneous risk’ per time unit of failure at time t ‘from cause 1’ given survival till just before t. Similarly, the parameters in Table 3 are ratios between cause-specific hazards. Given the close similarity in interpretation, it is perhaps not entirely surprising that estimation of hazard rate parameters carries over to estimation of parameters in models for cause-specific hazards and, indeed, both the Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Cox regression model may be applied for cause-specific hazards in a fashion completely analogously to studies of all-cause mortality by censoring individuals failing from competing causes. We used this fact for the analyses in the Example in the ‘Competing risks’ section. The intuitive explanation is that both types of hazard rates describe what happens ‘locally in time’ among individuals still at risk. The formal explanation is that the likelihood factorizes.5

To estimate risks, the results from a rate model may be plugged into Equation (2). However, as seen in the Example in the ‘Competing risks’ section, simple relationships between explanatory variables and cause-specific hazards do not lead to simple relationships between explanatory variables and cumulative incidences. Thus, though roughly identical relapse rates were seen for EBMT risk groups 0/1 and 2, the risk of relapse was higher for EBMT risk group 0/1 due to a lower rate of NRM for that group.

Such properties have motivated the development of models that directly link the cumulative incidence to explanatory variables. The most popular model of this kind was introduced by Fine and Gray8 and links the cumulative incidence to explanatory variables as does the Cox model for all-cause mortality.

Example

Table 4 shows the result of the Fine–Gray regression model for relapse and NRM.

Table 4.

Estimated regression coefficients (B), associated standard errors (SE), sub-distribution hazard ratios (HR) and associated 95% CIs of the EBMT risk groups for relapse and non-relapse, for Fine–Gray regression

| EBMT risk group | Relapse |

NRM |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | HR (95% CI) | B | SE | HR (95% CI) | |

| 0, 1 | ||||||

| 2 | −0.068 | 0.111 | 0.93 (0.75–1.16) | 0.443 | 0.116 | 1.56 (1.24–1.96) |

| 3 | 0.072 | 0.108 | 1.07 (0.87–1.33) | 0.661 | 0.114 | 1.94 (1.55–2.42) |

| 4 | 0.161 | 0.117 | 1.17 (0.93–1.48) | 0.906 | 0.118 | 2.48 (1.96–3.12) |

| 5, 6, 7 | 0.439 | 0.135 | 1.55 (1.19–2.02) | 1.185 | 0.131 | 3.27 (2.53–4.22) |

The most striking aspect is the fact that the regression coefficient of EBMT risk group 2 for relapse is less than 0 (though the 95% confidence limits do include 0). This means that the cumulative incidence of relapse of EBMT risk group 2 is less than that of EBMT risk group 0/1. This is in agreement with Figure 5, although that was derived from a proportional cause-specific hazards model.

Although the ‘relative sizes’ of the regression coefficients in the Fine–Gray model in a useful way reflect the ‘ordering’ of the cumulative incidence curves, their numerical values do not possess a simple interpretation. Thus, the estimates in Table 4 are ‘sub-distribution HRs’ and although this sounds like a HR, it is not. As noted above, the cause j-specific hazard gives the rate of cause j failure per time unit for individuals who are still alive. On the other hand, the cause j sub-distribution hazard gives the rate of cause j failure per time unit for individuals who are either ‘still alive’ or ‘have already died from causes other than j’.8 Thus, a sub-distribution hazard bears no resemblance to an epidemiological rate, since individuals who have died from another cause remain in the risk set, even though they are no longer at risk of experiencing a cause j failure. This fact does complicate the interpretation of parameters from the Fine–Gray model.

A final, technical note is that the structure assumed in a Cox model for the cause-specific hazards (‘proportional hazards’) is incompatible with that of the Fine–Gray model (‘proportional sub-distribution hazards’).9 This means that careful checking of the model assumptions is important, both when inference is based on Cox models for cause-specific hazards and when it is based on Fine–Gray models.

Model checking may, initially, be performed graphically. Figure 6 shows non-parametric estimates of the cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM for each of the five EBMT risk groups. The estimates of the relapse cumulative incidence curves for EBMT risks groups 0/1 and 2 cross. In the same way, as crossing survival curves for two groups in all-cause mortality are an indication that the proportional hazards assumption may be violated, this suggests that the proportionality assumption of the sub-distribution hazards for relapse in the Fine–Gray model may be violated for EBMT risks groups 0/1 and 2.

Figure 6.

Non-parametric cumulative incidence estimates for (A) relapse and (B) NRM for each of the five EBMT risk groups

A similar graphical way of checking the proportional hazards assumption of the proportional cause-specific hazards model is obtained by inspecting the non-parametric cause-specific hazard estimates of Figure 4. Also, here the proportional hazards assumption is questionable, although (also for the Fine–Gray model) it seems that only the EMBT risk group 0/1 for relapse is causing the non-proportionality. On the other hand, crossing of the estimated curves could just signal that the true functions are identical and the graphical examination can be complemented by formal significance testing, e.g. via the scaled Schoenfeld residuals as in a standard Cox model10 or following the lines of Andersen and Pohar Perme11.

‘Independent’ competing risks

Throughout, we have discussed the ‘rate of failure from cause j’ or the ‘risk of failure from cause j’ but never the ‘time to failure from cause j’. This is because for some individuals failure from cause j will never occur and thereby, formally, allowing ‘time to failure from cause j’ to be infinite. In contrast, a classical approach to competing risks is via latent failure times as briefly summarized by Kalbfleisch and Prentice12 (see Section 8.2.4). In that approach one imagines the existence of random variables, L1, L2, representing time to failure from Cause 1 and time to failure from Cause 2, respectively. The data then include the smaller of L1 and L2 (T = time to failure) and the cause of failure (1 if T = L1, 2 if T = L2). (Right-censoring may be accounted for.) This approach has led to the concept of ‘independent’ competing risks defined by independence between L1 and L2. Under ‘independence’ the available incomplete observations of, e.g. L1, are the same as those that would have been observed in a hypothetical population where Cause 2 is not operating. However, the assumption turns out to be completely unverifiable based on data from this world where Cause 2 is, indeed, operating.13,14 Therefore, we believe that the concept of ‘independent’ competing risks is quite elusive and that analyses relying on ‘independence’, e.g. estimating the distribution of L1 using one minus the Kaplan–Meier estimator, censoring for Cause 2, should be interpreted with great care. However, we will argue that the concept of ‘independence’ is not really needed for inference. This is because the cumulative incidence may always be estimated using Equation (2) and rates of Cause 1 may be analysed by, formally, treating Cause 2 events as censorings and vice versa. The latter technique solely relies on the definition of cause-specific hazards as the time-local rates of occurrence of events that are mutually exclusive (or, more precisely, on the resulting likelihood factorization) and not on any independence assumption.

Discussion

In epidemiology, rates and risks are frequently used as measures of disease incidence and in this paper we have reiterated the fact that, in studies of all-cause mortality, they are equivalent due to their one-to-one correspondence [Equation (1)]. However, whereas both concepts generalize quite simply to the competing risks situation (rates are now cause-specific hazards and risks are cumulative incidences), a one-to-one correspondence between a single rate and the corresponding risk no longer exists. Thus, any given cumulative incidence depends on all cause-specific hazards [Equation (2)] and vice versa, and even though a single ‘sub-distribution hazard’ may be derived from a single cumulative incidence, this is not a rate in any standard epidemiological sense. Similarly, a ‘risk-type quantity’ may formally be defined by plugging a cause-specific hazard into Equation (1). However, the resulting ‘risk’ may only be interpreted in a completely hypothetical world where the competing risk does not exist, see ‘Independent competing risks’ section. This is also illustrated by the fact that the Kaplan–Meier estimator provides a biased estimate of the cumulative incidence in the presence of competing risks as demonstrated in our example.

Another consequence of the lack of a one-to-one correspondence between rate and risk in a competing risks setting is that covariates may affect the cause-j specific hazard and the cause-j cumulative incidence differently. This was also illustrated in our example showing that, when it comes to regression modelling, there is a choice to be made whether models should focus on cause-specific hazards or on cumulative incidences. Cox regression models for cause-specific hazards have the advantage that they are easy to fit (simply censor for competing events) and they provide parameter estimates which possess simple rate ratio interpretations. Such models, however, do not provide simple relationships between covariates and the easier interpretable cumulative incidences. Such simple relationships may be obtained from Fine–Gray models but the price to be paid is a set of parameter estimates which are harder to interpret.

These properties, together with assessment of model fit, should be kept in mind when deciding on how to make inference in a competing risks situation. We believe, as also illustrated by our example, that both rates and risks for all competing events remain useful and tend to supplement each other when studying models for competing risks. Cause-specific hazards may be more relevant when the disease aetiology is of interest, since it quantifies the event rate among the ones at risk of developing the event of interest. Cumulative incidences are easier to interpret and are more relevant for the purpose of prediction.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant number R01-54706-12 to P.K.A.), the Danish Natural Science Research Council (grant number 272-06-0442 ‘Point process modelling and statistical inference’ to P.K.A.) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (grant number ZONMW-912-07-018 ‘Prognostic modeling and dynamic prediction for competing risks and multi-state models’ to H.P.).

Acknowledgement

The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) is gratefully acknowledged for providing the data.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

Competing risks are the rule rather than the exception in epidemiological studies.

In all-cause mortality, there is a one-to-one relation between rate and risk; this one-to-one correspondence is lost in competing risks.

The naïve Kaplan–Meier that takes competing events as censored is a biased estimate of the cumulative incidence function.

The way in which covariates are associated with the cause-specific hazards may not coincide with the way these covariates are associated with the cumulative incidence.

The concept of independent competing risks is elusive, cannot be checked without additional restrictive assumptions, but is not needed for inference on rates or risks.

References

- 1.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.dos Santos Silva I. Cancer Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen J, Christensen K, Murray J, Ekbom A. An Introduction to Epidemiology for Health Professionals. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton DG, Hills M. Statistical Models in Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gratwohl A, Hermans J, Goldman JM, et al. Risk assessment for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia before allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1998;352:1087–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grambauer N, Schumacher M, Beyersmann J. Proportional subdistribution hazards modeling offers a summary analysis, even if misspecified. Stat Med. 2010;29:875–84. doi: 10.1002/sim.3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geskus RB. Cause-specific cumulative incidence estimation and the Fine and Gray model under both left truncation and right censoring. Biometrics. 2011;67:39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen PK, Pohar Perme M. Pseudo-observations in survival analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19:71–99. doi: 10.1177/0962280209105020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2nd. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR. The analysis of exponentially distributed life-times with two types of failure. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1959;21:411–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsiatis AA. A nonidentifiability aspect of the problem of competing risks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:20–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]