Summary

The Ouagadougou Health and Demographic Surveillance System (Ouaga HDSS), located in five neighbourhoods at the northern periphery of the capital of Burkina Faso, was established in 2008. Data on vital events (births, deaths, unions, migration events) are collected during household visits that have taken place every 10 months. The areas were selected to contrast informal neighbourhoods (∼40 000 residents) with formal areas (∼40 000 residents), with the aims of understanding the problems of the urban poor, and testing innovative programmes that promote the well-being of this population. People living in informal areas tend to be marginalized in several ways: they are younger, poorer, less educated, farther from public services and more often migrants. Half of the residents live in the Sanitary District of Kossodo and the other half in the District of Sig-Nonghin.

The Ouaga HDSS has been used to study health inequalities, conduct a surveillance of typhoid fever, measure water quality in informal areas, study the link between fertility and school investments, test a non-governmental organization (NGO)-led programme of poverty alleviation and test a community-led targeting of the poor eligible for benefits in the urban context. Key informants help maintain a good rapport with the community. The Ouaga HDSS data are available to researchers under certain conditions.

Why was the Health and Demographic Surveillance System created?

Development efforts in Sub-Saharan Africa are focused mainly on rural areas. Although rural citizens are indeed poorer than urban dwellers on average, strong inequalities exist within cities. In fact, the vulnerable fringe of the urban population could experience worse living conditions than rural inhabitants, due to the combined effect of persistent poverty and problems specific to the urban environment (such as criminality, housing density, pollution, road accidents, unhealthy diets, weakening of social control and links, etc.). Moreover, the proportion and the number of urban dwellers is increasing rapidly on the continent. Whereas 15.5% of the Burkina Faso’s population was urban in 1996, this number is expected to rise to 40% by 2030. Whereas Ouagadougou counted 170 000 inhabitants in 1975, this number had soared to 1.5 million by 2006 and is expected to reach 5.8 million by 2030.

In order to tackle the problems of the urban poor, the Institut Supérieur des Sciences de la Population (ISSP) at the University of Ouagadougou established a pilot demographic surveillance system in Ouagadougou in 2002. This pilot covered 5000 inhabitants living in one informal and one formal neighbourhood. The pilot showed that collecting data on Pocket PCs rather than on paper questionnaires led to a significant decrease in data production costs. The pilot also showed that despite high in- and out-migration rates, an important proportion of city dwellers enjoy residential stability in Ouagadougou. The Ouaga HDSS joined the INDEPTH network in 2005.

What does it cover now?

In 2008, thanks to a grant from the Wellcome Trust, the ISSP extended the population covered to 80 000 residents. The first research programme of the Ouaga HDSS, to be completed in 2012, uses a mixed-method approach (quantitative, qualitative and spatial analysis) to describe the double burden of disease and health care utilization characterizing the areas, and its unequal distribution according to different dimensions of vulnerability: type of neighbourhood (formal or informal), poverty, lack of education, migrant status and age.

Subsequently, other research projects have started in the Ouaga HDSS: a study on fertility and schooling, a surveillance of typhoid fever, a measure of water quality in informal areas and its variation with climate change, the test of a non-governmental organization (NGO)-led programme of poverty alleviation, the test of a community-led targeting process identifying the poorest poor eligible for health benefits in the urban context and a programme of comparative analyses with the Nairobi HDSS.

Where is the HDSS area?

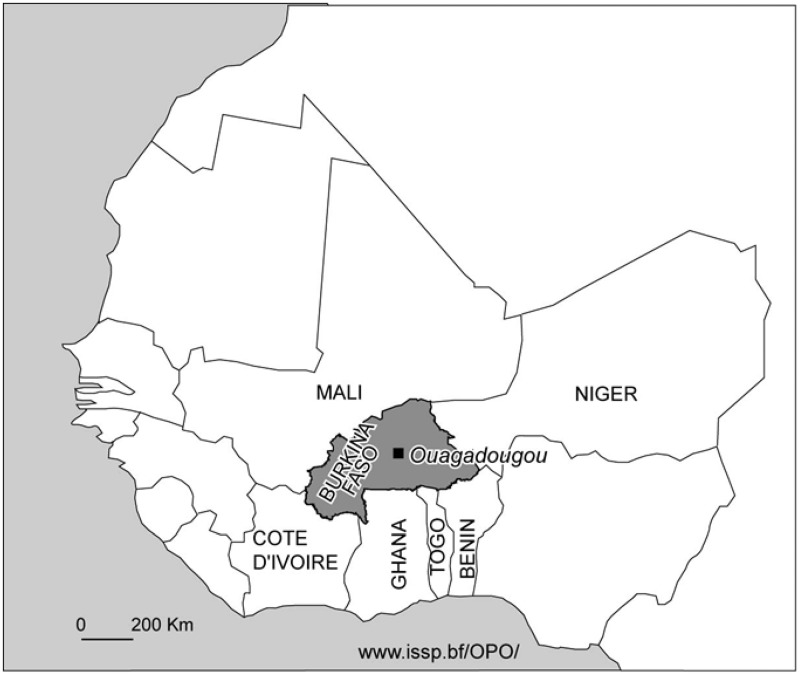

Ouagadougou is the capital city of Burkina Faso and lies at the centre of this country, located in the middle of West Africa (12° North of the Equator and 1° West of the Prime Meridian) (Figure 1). The rainy season lasts from June to October; the rest of the year is dry. Temperatures range from 15°C in December to 42°C in April. Most city dwellers work in the trade sector. Several major national public hospitals are located in the capital along with most private health centres and pharmacies.

Figure 1.

Location of Ouagadougou in West Africa

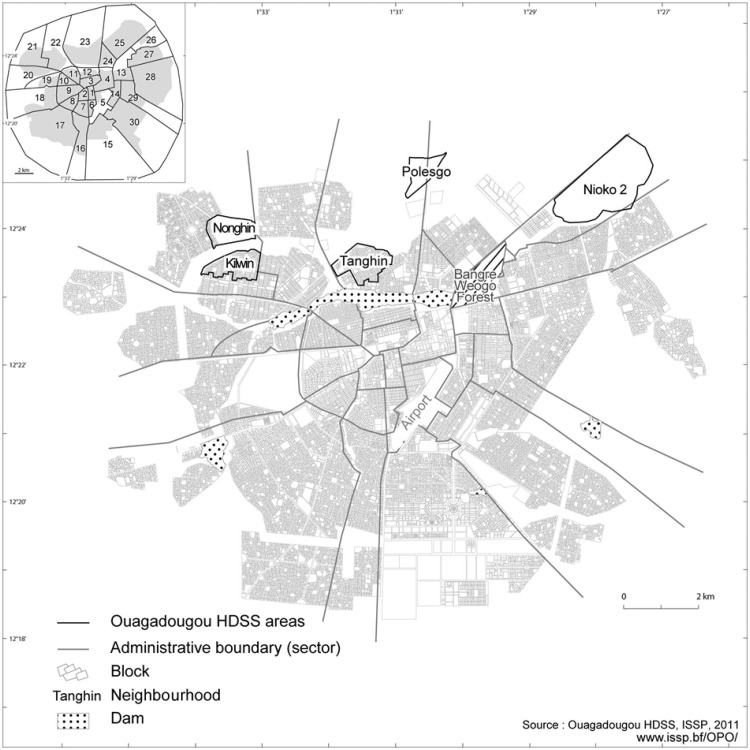

The Ouaga HDSS sites were chosen to target the most vulnerable populations of the city. We thus paid special attention to areas of unplanned growth. Information given by the municipalities led us to choose three informal areas devoid of formal zoning plans, located at the northern periphery of the city: Nonghin, Polesgo and Nioko 2. To be able to compare these areas with the rest of the city, we added two formal neighbourhoods located close by (Kilwin and Tanghin) (Figure 2). Nonghin and Kilwin belong to the Sanitary District of Sig-Nonghin, whereas Polesgo, Tanghin and Nioko 2 belong to the Sanitary District of Kossodo. A population of 80 000 was defined as a minimum to measure differences in child mortality in a ‘control’ vs an ‘intervention’ area given the 1996 census urban level of mortality in Burkina Faso, and we distributed this total amount equally between formal and informal areas, and between the districts of Kossodo and Sig-Nonghin. The Ouaga HDSS areas cover only part of either district.

Figure 2.

Location of settlements monitored by the Ouagadougou HDSS

In September 2008, we defined the limits of our areas using existing census tracks (census 2006), and creating new ones in places where the city had expanded. Altogether, the areas we followed consist of 55 census tracks divided into 494 blocks. We mapped all the census tracks and blocks using fieldworkers with handheld global positioning system (GPS) receivers and ArcGIS 9. During a first census (October 2008 to March 2009), the demographic surveillance system was explained to every head of household and a consent form was signed; during subsequent censuses, new households are enrolled in the same way.

Who is covered by the HDSS and how often have they been followed up?

Fieldworkers first enumerated all the Units of Collective Habitation (UCH). A UCH is defined as one or several buildings, of which at least one could be rented or is inhabited, and which are either enclosed, or belong to the same owner. In formal areas, the UCH correspond to city plots, and city numbers are used; in informal areas, an ad hoc identification (ID) number is created and painted on the UCH wall. The geographic coordinates of each UCH were measured, using the GPS function on the Pocket PC. Each UCH contains one or several households; every household belongs to one and only one UCH. A resident is defined as a person who has lived for more than 6 months in a UCH. By living, we mean ‘usually sleeping’ in the UCH, that is, sleeping more frequently in the UCH than anywhere else. A household is defined, within a UCH, as a group of residents (related by family links or not), who put their resources together to collectively satisfy most of their vital needs. Additionally, household members must recognize one member as the head of household.

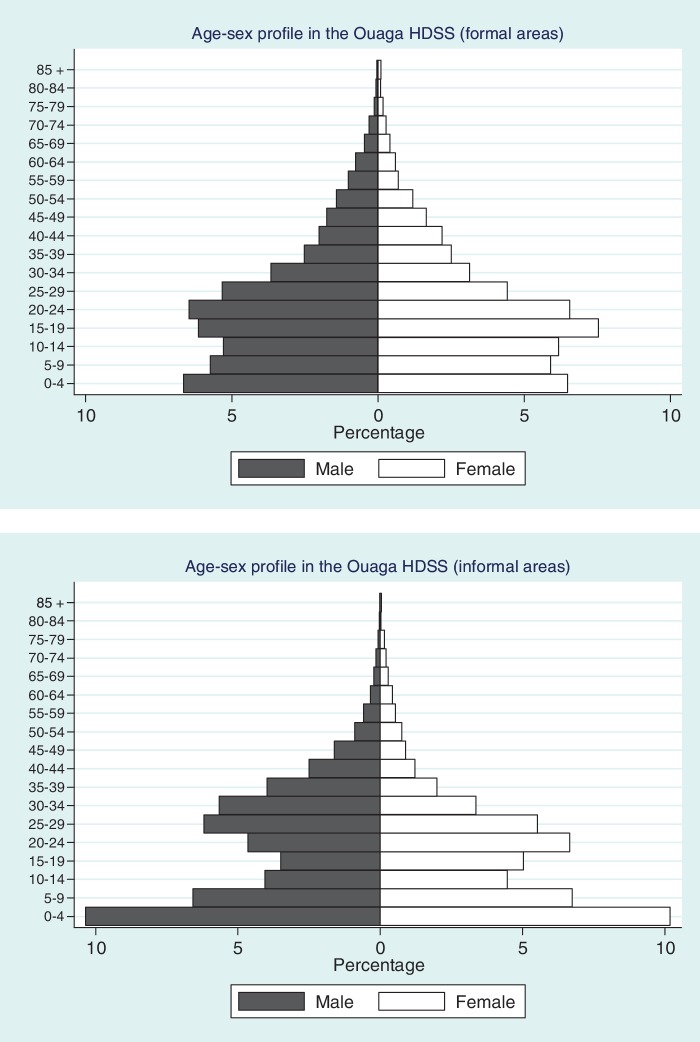

During the third enumeration (mid-point: June 2010), there were 81 717 residents (37 878 in informal areas and 43 839 in formal areas), living in 18 310 households. The average household size was 3.6 in informal areas and 5.7 in formal ones. The male:female ratio was 100.6:100. Among residents, 39% were under 15 years and 16% were under 5 years. The age pyramid differs between formal and informal areas (Figure 3), with a more regular shape in formal areas, albeit with peaks between the ages of 10 and 24 years for women and 15 and 29 years for men, denoting the flux of migrants from rural areas; most residents in informal areas are young adults with small children.

Figure 3.

Age pyramid, Ouagadougou HDSS, formal and informal areas, 2010

Between October 2008 and April 2012, the fieldworkers conducted four enumerations. They use standard forms to enumerate all UCH, households and residents (the forms are available on http://www.issp.bf/OPO/DATASET/Questionnaire.html). The forms appear on the screen of their Pocket PCs, which have been loaded with the information from the last census concerning the block they are working in. A series of validity checks are built in the programme of the Pocket PC. Each night, the data collected are transferred by Wifi to a server. A validity check is run every 2 weeks on the new data, and errors are corrected. At the end of the enumeration, the new data are merged with the rest of the database, and further errors are detected and corrected.

In the initial census, two households refused to participate in the surveillance system, and by February 2011, the number of non-participating households rose to 40. In case of a refusal, the fieldwork supervisor visits the household to try to address any concerns. At the start of the project, local authorities and personalities gathered for several informational sessions; radio programmes and town criers were used to raise awareness about the project. Constant communication is maintained in the informal areas through a network of 12 key informants. In all neighbourhoods, fieldwork supervisors visit local authorities and recognized community representatives for updates. As called for by local custom, following any death, the supervisors visit the household for a greeting and a symbolic donation.

What has been measured and how have the HDSS databases been constructed?

At re-enumeration, fieldworkers register any demolished or newly constructed UCH. Within each UCH, fieldworkers enumerate existing households, and register new ones. They interview one member of each household and collect data on the vital events that occurred to any household members since the last census (Table 1). They verify that individuals registered on the household list did indeed sleep in the UCH the previous night, and if not, when they last left. They collect data on residents who have died since the last census (and on residents who have been gone for more than 6 months). Another trained fieldworker returns to bereft households to perform a verbal autopsy using the standard INDEPTH forms (paper questionnaires); a group of eight local medical doctors performs a double diagnosis of each case; discordant cases are discussed and resolved by the group. Fieldworkers ask about births that have occurred since the last census (women aged 12–49 years), paying close attention to births that may have led to deaths. The pregnancy status of each woman is ascertained, as well as the outcome of any previously registered pregnancies. The marital status of residents is updated. Finally, fieldworkers register newcomers, and search for their ID if they have already lived in the area and were recorded. They collect basic information about visitors, and brief histories of migration, marriages and births for new adult residents.

Table 1.

Information collected at each re-enumeration round of the Ouagadougou HDSS

| Subject information |

| UCH |

| Latitude, longitude |

| Number of buildings, number of households, enclosed or not |

| Name of owner |

| Household |

| Household name |

| Household head |

| Household assetsa (telephones, bicycles, motorcycles, cars, refrigerators, televisions, DVDs) |

| Home ownershipa |

| Housing characteristicsa (access to water, energy used for cooking and lighting, waste management, type of toilet, floor, wall and roof materials) |

| Individuals |

| Names,3 sex, date of birth, ethnic group, relation to household head |

| Update of residency status (resident, died, out-migrated) |

| Update of pregnancy status for women aged 15–49 years |

| Survival of biological parentsa |

| Education levela (current class and school attended, last class attended) |

| Employment statusa (activity status, status in occupation, domain of occupation, searched for a job last week) |

| Vaccination history for children aged less than 5 yearsa |

| Unions |

| Date of cohabitation |

| Date of civil ceremony, date of religious ceremony, date of traditional ceremony |

| Number of spouse(s) for men |

| Resident spouse’s personal identity number (link) |

| Births |

| Date and place of birth |

| Medical attendance at birth |

| Names,3 sex of child, ethnic group, relation to household head |

| Height, weight, vaccinations, prenatal visits |

| Mother’s and father's personal identity number (link) |

| Wantedness status of birth, civil registration of birth |

| Deaths |

| Date of death |

| Place of death |

| Verbal autopsy |

| In-migration |

| Date of in-migration |

| Names,3 sex and date of birth of migrants |

| Origin of migration episode |

| Reason for migration episode |

| Previous residence within the Ouaga HDSS |

| Out-migration |

| Date of out-migration |

| Destination of migration episode |

| Reason for migration episode |

| Pregnancy |

| Outcome of existing pregnancy records |

| Date of delivery, number of babies, stillborn, live-born |

aThis information is collected every two rounds.

At every other enumeration, data are collected on the vaccination history of children under 5 years, on the survival of biological parents and on household goods, economic activities, education, home ownership and housing characteristics (Table 1).

These data are stored in 25 relational tables organized around objects, events and episodes, such as individuals, births or episodes of household headships. The most frequently used data are reorganized in eight macro files. SQL Server Pro is the data managing system.

In addition, between February and August 2010, we conducted a health survey on a sample of residents under 5 years or over 15 years of age, over-sampling children and the elderly. We drew a sample of 1941 households, of which 1699 responded (a response rate of 87.5%); 3307 individuals (their mothers for children) were interviewed: 950 were under 5 years, 1371 were between 15 and 49 years and 986 were 50 years and over. Weights were calculated taking the non-responses and the stratified sampled procedure into account. The survey was conducted on Pocket PCs. The children’s questionnaire included the following modules: infectious disease symptoms, mosquito net use, accidents and violence, access to health care, anthropometric measures (weight, height and arm circumference). The adult questionnaire included questions on self-reported health, physical and cognitive limitations, depression, behavioural risk factors, accidents and violence, access to health care, anthropometric measures (weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure). Individuals 50 years and older were asked additional questions on physical limitations, economic independence, pension and support system and cognitive function. Women aged 15–49 years were asked additional questions on sexual activity, the desire for children, current pregnancy status and contraceptive use.

We further conducted a qualitative characterization in the neighbourhood in 2008–09, a qualitative investigation of the perception of the September 2009 flooding in Ouagadougou and a qualitative description of poverty in the areas in 2011. A database of health infrastructures in the whole city (including GPS coordinates) was created in 2009–10, and the geographic coordinates of all stagnating water and piles of trash were collected in the Ouaga HDSS areas in 2010.

Key findings and publications

The demographic indicators of the Ouaga HDSS are summarized in Table 2. Informal areas are inhabited mainly by young families with small children.1 Although residents of informal areas go to health centres when their children are sick as often as those who live in formal areas,2 they lack access to public schools and have to resort to expensive private schools despite their greater poverty.3 Informal areas are also the unhappy intersection of a high concentration of young children and particularly unsanitary living conditions,4,5 and as a result, infant mortality is almost twice as high in informal areas as in formal ones.6 Childhood malnutrition is still an important problem for the poor and in informal areas.7 On the other hand, adults living in informal areas do not seem to have a comparative disadvantage in terms of health outcomes.8 They seek formal health services less often when they are sick (because they are more often poor, uneducated and migrants from rural areas)2 but they are also less exposed to certain diseases and risk factors that are more prevalent among the middle class and in formal areas (such as obesity, road accidents and perhaps even HIV).6,8 The picture is similar when considering migration status as a source of vulnerability. With all else constant, migrants and non-migrants seem to have similar health outcomes, although further longitudinal analysis is necessary to exclude the hypothesis of selective out-migration.7 The favourable situation of migrants could be explained by their rapid social integration.3 Indications of social learning effects in the community (people surrounded by more educated individuals use cheaper counterfeit drugs less frequently, everything else being constant),9 predict that the effects of health education programmes are likely to be multiplied by social interaction effects. The lower contraceptive prevalence among poor and migrant couples seems less due to a lack of information, distance or financial constraints, than to persisting ideals of larger family.3,10

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the Ouagadougou HDSS

| Index result | |

|---|---|

| Total resident population* | 81 717 |

| Male:female ratio* | 100.6 |

| Population density* | 5559/km2 |

| Population growth/100 | 4.1 |

| Crude birth rate/1000 | 34.7 |

| Crude death rate/1000 | 4.6 |

| Crude out-migration rate/1000 | 108.5 |

| Crude in-migration rate/1000 | 126.5 |

| Crude trans-migration rate/1000a | 4.1 |

| Total fertility rate | 2.5 |

| Neonatal mortality ratio/1000 live births | 3.8 |

| Infant mortality ratio/1000 live births | 18.5 |

| Under 5 mortality ratio/1000 live births | 48.5 |

| Life expectancy at birth (males) | 66.4 years |

| Life expectancy at birth (females) | 76.2 years |

All figures are averages for the period January 2009 to December 2011 except those marked with asterisk, which are taken from the third enumeration round with a mid-point date of 23 June 2010.

aThe transmigration rate is the rate of moving residence where the starting residence and the finishing residence are both households within Ouaga HDSS.

We also shed some light on some new public health concerns in the African context. Of the adults, 4.5% were estimated to be depressive at the time of the survey, a level that is not negligible; depression appears to be mainly related to identified chronic health conditions and physical limitations.11 The elderly (3% of the Ouaga HDSS population are 60 years and over) either still work or are supported by their spouses or children. Women whose husbands die (at any age) are in especially vulnerable positions when they have no sons to support them.12

Plans for future analysis

In collaboration with researchers at Pennsylvania State, University of Louvain and McGill University, we plan to study the evolution of household poverty and its relation to family planning behaviours, the relation between migration and child mortality controlling for out-migration, and the relationship between single-mother households and child mortality. In collaboration with the Burkinabe Ministry of Health, local NGOs and international research teams, we plan to test two community-based interventions in the Ouaga HDSS areas: an innovative dual prevention (HIV and family planning) programme for young people and a community-based family health education programme with a focus on chronic diseases.

Main strengths and weaknesses

The main strength of Ouaga HDSS is its location: it follows an urban population, where poor individuals are overrepresented, but which is also socio-economically diverse. Research on urban dwellers and the urban poor is needed in Africa. Another strong point is the stable population of Ouaga HDSS. Although migratory movements are important in both directions (we observe a 6.2% population increase in our areas 1.5 years after initial enumeration, which we break down into 7.9% out-migrations, 11.4% in-migrations, 0.5% deaths and 3.3% births), a core part of the population owns their homes (82% of households in informal areas and 62% in formal areas in 2009) and enjoys residential stability. In fact, 92% of the residents at the first enumeration were still there at the second enumeration that took place 1.5 years later.

However, the Ouaga HDSS also has some weaknesses. First, it is not representative of the city of Ouagadougou as a whole, because it does not extend to the centre of the city, which is more densely populated by Ouagadougou natives and older people. Also, the Ouaga HDSS cannot be used to test some hospital-based interventions, because the areas followed do not correspond to the entire catchment area of the collaborating reference hospitals.

Another issue is a partial measure of migration. Some migrants fail to establish themselves, and becoming a resident is a highly selective process. Although we collect data on ‘visitors’, no information allows us to distinguish those who may have wanted to migrate among them and have failed. We observe that residents do not often declare spending several months a year in their previous location; however, back-and-forth migrants are likely to never even become residents given our residency definition. Moreover, the matching procedure designed to find the ID of individuals having already lived in our areas often fails for technical reasons; in-migrations are thus overestimated and moves within the areas (and returns to the area) not well measured. Finally, we do not know how many residents move out to give birth or to get health care (and die), or how many new residents may have moved in for similar reasons.

There are also some data quality issues. During the first re-enumeration, we had difficulties finding individuals at home despite three mandatory visits per household, and data are missing for about one household out of five. Changes in the organization of fieldwork in the subsequent enumerations seem to have fixed the problem. Also, despite the use of national ID cards or other official documents to determine the date of birth for most individuals, the elderly (especially women) seem to have exaggerated ages. Finally, we seem to have been missing a number of neonatal deaths during the first two re-enumerations. Forms were modified for the third enumeration.

Data sharing and collaboration

Basic descriptive data, questionnaires and maps are available on the Ouaga HDSS web site (www.issp.bf/OPO). Anonymous, individual record-level data are also available, subject to approval by the Ouaga HDSS coordination team. Requests for scientific analyses should include one researcher with an ISSP affiliation in the scientific production team. Interested researchers should use the forms provided on the web site, specifying the purpose of the work and the expected output; forms should be sent to Clémentine Rossier (clementine.rossier@ined.fr or crossier@issp.bf).

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust, grant number WT081993MA.

Acknowledgements

We thank the people in Nonghin, Kilwin, Polesgo, Tanghin and Nioko 2. We acknowledge the great work of the field staff and their importance in maintaining a good rapport with the population, in particular the work of its team leaders, M. Kouanda, M. Ouedraogo, A. Palenfo and P. Ziba. We thank the computer programmers who have worked tirelessly: M. Niang, A. Kambou, F. Hien, K. Kombassere and D. Dielbeogo. We would like to thank the scientific advisory committee that was of tremendous help during the duration of the project: P. Antoine, J. Brown, V. Delaunay, B. Kouyaté, P. Ngom, J. Philips. We would like to thank C. Mbacke and T. Legrand for their enduring support for the project. We are also greatly indebted to the people of Taabtenga and Wemtenga, the Rockefeller Foundation and G. Pictet, without whom the pilot would have not existed.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

The Ouaga HDSS is the only urban demographic surveillance system in West Africa.

Children living in informal neighbourhoods are subjected to higher mortality rates due to particularly unsanitary living conditions.

Health inequalities are lower than expected among adults because of a high exposure to chronic diseases and road accidents among the non-poor.

References

- 1.Rossier C, Lankoande B, Ortiz I. Fertility differentials in formal and informal neighborhoods of Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=151 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikiema A, Rossier C, Millogo R, Ridde V. Inégalités de l’accès aux soins en milieu urbain africain: le cas de la périphérie nord de Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=805 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossier C, Ducarroz L. La pauvreté dans les quartiers de l’Observatoire de Population de Ouagadougou: une approche qualitative. [Monograph on the internet]. Université de Ouagadougou: Institut Supérieur des Sciences de la Population; 2012. www.issp.bf\OPO (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djourdebbe B, Dos Santos S, Legrand T, Soura A, Nikiema A. Effet de l’environnement proche sur la survenue de la fièvre chez les enfants de moins de 5 ans à Ouagadougou: le cas des zones de l’Observatoire de Population de Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=851 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dos Santos S, Djourdebbé B, Nikiéma A, Peumi JP, Soura A. Risques environnementaux et santé des enfants. Caractérisation des populations et des quartiers à risque à Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=1804#17 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossier C, Soura A, Lankoande B. Poverty and health at the periphery of Ouagadougou. In New Approaches to Urban Health and Mortality during the Health Transition; 14–17 December 2011; Sevilla. Spain. http://www.iussp.org/ (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossier C, Soura A, Lankoande B. Migration, pauvreté et santé à la périphérie de Ouagadougou; Chaire Quételet; 16–18 November 2011; University of Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. http://www.uclouvain.be/374709.html (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zeba A, Delisle H, Renier G, Savadogo B, Baya B. The double burden of malnutrition and cardio-metabolic risk widens the gender and socioeconomic health gap: a study among adults in Burkina Faso (West Africa). Pub Health Nutr. 2012; doi:10.1017/S1368980012000729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Soura A, Baya B, Rossier C. Utilisation des médicaments de la rue à Ouagadougou: effet de niveau de vie ou effet de niveau d’éducation. Rev Géo Lomé. 2011;7:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossier C, Ortiz I. Unmet needs for contraception in formal and informal neighborhoods of Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=352 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duthé G, Bonnet D, Rossier C. Dépression et vulnérabilité sociale à Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=1552 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Léger V, Randall S, Baya B. Dimensions de bien-être des personnes âgées à Ouagadougou. 6th African Population Conference; 5–9 December 2011; Ouagadougou. http://uaps2011.princeton.edu/sessionViewer.aspx?SessionId=404 (7 May 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]