Abstract

Background

Because of the distinct clinical presentation of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer, we aim to clarify whether these disease entities are solely separated by time of diagnosis or whether they arise from distinct molecular events.

Methods

Sixteen early and sixteen advanced stage ovarian carcinomas, matched for histological subtype and differentiation grade, were included. Genomic aberrations were compared for each early and advanced stage ovarian cancer by array comparative genomic hybridization. To study how the aberrations correlate to the clinical characteristics of the tumors we clustered tumors based on the genomic aberrations.

Results

The genomic aberration patterns in advanced stage cancer equalled those in early stage, but were more frequent in advanced stage (p = 0.012). Unsupervised clustering based on genomic aberrations yielded two clusters that significantly discriminated early from advanced stage (p = 0.001), and that did differ significantly in survival (p = 0.002). These clusters however did give a more accurate prognosis than histological subtype or differentiation grade.

Conclusion

This study indicates that advanced stage ovarian cancer either progresses from early stage or from a common precursor lesion but that they do not arise from distinct carcinogenic molecular events. Furthermore, we show that array comparative genomic hybridization has the potential to identify clinically distinct patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13402-012-0077-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oligonucleotide array, Ovarian neoplasms, Chromosome aberrations, Neoplasm staging, Prognosis

Introduction

Despite improved survival over the last decades, ovarian cancer is still the most lethal gynaecological malignancy in the Western world, with a 5-year overall survival of only 25 % for advanced stage [1, 2]. In contrast, patients diagnosed at an early stage have a good 5-year overall survival rate of 93 %. Early stage ovarian cancer, however, is only diagnosed in 19 % of the patients.

Like other malignancies, epithelial ovarian cancer presumably results from an accumulation of genomic aberrations [3], but the exact molecular pathways by which these tumors develop have not been fully elucidated [4, 5]. For other tumors, such as cervical and anal cancer, intraepithelial neoplasia is known to be a precursor lesion. However, no clear precursor lesion is known for ovarian cancer. Therefore, the first clinical entity to study carcinogenesis of ovarian cancer in patients is minimal localized cancer (FIGO stage I disease). As a small percentage of the patients is diagnosed with early stage ovarian cancer, it has been hypothesized that early and advanced stage ovarian cancers are two distinct subtypes. Early stage ovarian cancer (with a good prognosis) may represent a distinct biological entity with low metastatic potential and would thus arise through a different carcinogenic pathway. It has been suggested that these early cases are molecularly distinguishable from the advanced stage ovarian cancer with a worse prognosis [6].

Copy number change is one of the key features of genetic instability in human cancer and can be measured in formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue (FFPE)[7]. To test the hypothesis that early and advanced stage ovarian cancers are distinct molecular pathologic entities, we used array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) to detect and compare genomic aberrations in matched early and advanced stage ovarian tumors. Furthermore, we study how the aberrations correlate to the clinical characteristics of the tumors[8].

Materials and methods

Patients and tumor tissue

FFPE primary ovarian tumor tissue of 52 early stage ovarian cancer patients (FIGO stage I), was available from 448 participants of the EORTC ‘Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm’ (ACTION) trial [9–11]. Of these 52 samples, 17 early stage samples with high quality DNA were matched for histological subtype and grade with FIGO stage III–IV (advanced stage) ovarian cancer samples from the Departments of Pathology of the University Medical Center Utrecht and VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, The Netherlands. FIGO stage was determined by optimal staging in all but four of the patients with advanced stage cancer. Staging was optimal (n = 7), modified (n = 3) or minimal (n = 7) as previously described [9]. In short, optimal staging consisted of inspection and palpation of all peritoneal surfaces; biopsies of any suspect lesions for metastases; peritoneal washing; infracolic omentectomy; (blind) biopsies of right hemidiaphragm, of right and left paracolic gutter, of pelvic sidewalls, of ovarian fossa, of bladder peritoneum, and of cul-de-sac; sampling of iliac and periaortic lymph nodes. Modified comprised of everything between optimal and minimal staging. Minimal staging was only inspection and palpation of all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal area; biopsies of any suspect lesions for metastases; peritoneal washing and infracolic omentectomy.

All samples were revised by an experienced gynaecological/oncological pathologist (PvD). The tumor percentage was defined by the pathologist per individual case; mean 77.8 % (SD 7.5), median 80 % range [65–95]. Samples were processed anonymously in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines, and follow up was retrieved through the EORTC ACTION trial database and the hospital information system for the early and advanced stage tumors respectively. Overall and progression free survival times were calculated from the time of randomization (within 6 weeks following staging) or the date of surgery for the early and advanced stage tumors respectively.

The age range was 27–80 years with a mean of 52 years for early and 62 years for advanced stage carcinomas. In six cases, an exact match for grade was unavailable. In these cases we matched with one grade difference being a grade 1 early with grade 2 advanced (n = 4), and a grade 2 early with grade 3 advanced (n = 2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all 32 patients included in this study. Overall (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) are calculated from time of randomization in the early (T102-T118) and time of diagnosis in advanced stage group (T302-T318). Histological subtypes are indicated as clearcell (C), endometrioid (E), mucinous (M) or serous (S). Adjuvant Chemotherapy (CT) was administered to a subset of patients. The results of the unsupervised clustering analysis are displayed as cluster A or B

| Sample | Age | Stage | Type | Grade | CT | Staging | Status | OS (month) | Progression | PFS (months) | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T102 | 70 | Ic capsule ruptured | C | 2 | no | optimal | Alive | 42 | no | 42 | A |

| T103 | 61 | Ic capsule ruptured | C | 3 | yes | optimal | Alive | 154 | no | 154 | A |

| T104 | 61 | Ia | C | 3 | yes | optimal | Dead | 13 | yes | 10 | A |

| T105 | 47 | Ia | C | 3 | no | minimal | Alive | 136 | no | 136 | A |

| T106 | 64 | Ic capsule ruptured | C | 3 | no | optimal | Alive | 39 | no | 39 | A |

| T108 | 41 | Ic capsule ruptured | E | 1 | yes | minimal | Alive | 73 | no | 73 | A |

| T109 | 55 | Ib | E | 1 | yes | minimal | Alive | 137 | no | 137 | A |

| T110 | 64 | Ic ascites positive | E | 1 | no | modified | Alive | 49 | yes | 49 | A |

| T111 | 46 | Ic ovarian surface | E | 2 | no | minimal | Alive | 146 | no | 146 | A |

| T112 | 53 | Ic capsule ruptured | E | 2 | yes | minimal | Alive | 44 | no | 44 | A |

| T113 | 42 | Ic capsule ruptured | M | 1 | no | optimal | Alive | 69 | no | 69 | A |

| T114 | 35 | Ia | M | 2 | no | optimal | Alive | 152 | no | 152 | A |

| T115 | 27 | Ia | S | 1 | yes | minimal | Alive | 65 | no | 65 | A |

| T116 | 62 | Ia | S | 1 | no | minimal | Alive | 59 | no | 59 | B |

| T117 | 50 | Ic ascites positive | S | 1 | no | modified | Dead | 61 | yes | 7 | B |

| T118 | 53 | Ia ovarian surface | S | 3 | no | optimal | Alive | 175 | no | 175 | A |

| T302 | 47 | III | C | 2 | yes | optimal | Dead | 17 | yes | 17 | B |

| T303 | 57 | IV | C | 3 | yes | incomplete | Dead | 9 | yes | 8 | B |

| T304 | 51 | III | C | 3 | yes | incomplete | Dead | 14 | yes | 14 | A |

| T305 | 74 | IIIb | C | 3 | yes | optimal | Dead | 60 | yes | 47 | B |

| T306 | 48 | IIIa | C | 3 | yes | optimal | Alive | 104 | no | 104 | B |

| T308 | 45 | IV | E | 2 | yes | optimal | Dead | 19 | yes | 9 | B |

| T309 | 47 | IIIc | E | 2 | yes | optimal | Dead | 41 | yes | 21 | B |

| T310 | 74 | IIIb | E | 2 | yes | optimal | Dead | 57 | yes | 57 | B |

| T311 | 67 | IIIc | E | 3 | yes | minimal | Dead | 61 | yes | 22 | B |

| T312 | 53 | IIIb | E | 3 | yes | optimal | Dead | 28 | yes | 28 | B |

| T313 | 67 | III | M | 1 | yes | optimal | Dead | 22 | yes | 22 | A |

| T314 | 76 | IV | M | 2 | yes | optimal | Dead | 15 | yes | 13 | A |

| T315 | 70 | IIIc | S | 1 | yes | optimal | Alive | 136 | no | 136 | A |

| T316 | 76 | IV | S | 1 | yes | optimal | Alive | 22 | yes | 22 | A |

| T317 | 80 | IIIc | S | 2 | yes | incomplete | Dead | 6 | yes | 5 | B |

| T318 | 61 | IIIc | S | 3 | yes | unknown | Dead | 5 | yes | 12 | B |

DNA isolation and detection of genomic aberrations by array CGH

Tumor tissue was dissected from freshly cut 10 μm FFPE sections after confirming the tumor area by parallel haematoxylin and eosin staining. DNA was isolated as previously described [7, 12] using the QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA concentration and labelling quality were measured using NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Labelling with cyanine 3-dUTP (Cy3) and cyanine 5-dUTP (Cy5) nucleotides was performed using the array CGH labelling kit for oligo arrays according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA). DNA isolated from blood obtained from eighteen healthy females was pooled for use as a normal reference [13]. Free nucleotides were removed using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). DNA was hybridized to 105 K whole genome Oxford design microarrays containing over 99.000 unique in situ synthesized 60-mer oligonucleotides (GPL8693, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and hybridization was performed using the oligo array CGH/Chip-Chip Hybridization Kit 25 (Agilent). Each slide contained 2 arrays and one reference sample was hybridized per three tumor samples, as previously described [13]. Samples were hybridized overnight, were washed and subsequently scanned using a microarray scanner (Agilent, G2505B). Raw data of all the arrays performed are publicly available in the GEO database (accession number GSE24418).

Data analysis

Array CGH quality was assessed by means of the median absolute deviation (MAD) of the log2 ratios of a chromosome arm without a breakpoint [14]. Whereas all MAD values of the copy number changes on the q-arm of chromosome two were between 0.17 and 0.43, the MAD value of one advanced stage sample was 0.70. This sample and its early stage match were therefore excluded from further analyses, leaving 16 early versus 16 advanced stage cases. With this set of 32 samples power analysis has been performed. Log2ratios were median normalized across array [13], wave patterns were smoothed [15]. Segmentation was performed by using circular binary segmentation (CBS), since this method has shown to substantially reduce the false positives caused by the local trends in the data [16, 17]. Mode normalization was performed on the segmented data prior to automated identification of losses, gains and amplifications [16]. Dimension reduction was achieved by summarizing into regions with a threshold of 0.01, in order to accept a maximum of 1 % information loss. The frequencies of aberrations in both groups were estimated, and the false discovery rate corrected p-values (Chi-square) of a difference in occurrence of aberrations between both groups were calculated after dividing the genome into regions [18, 19]. Using a FDR of 15 %, more than 50 % of discriminative aberrations will be detected [20]. To test whether advanced stage progresses from early stage, we tested whether the odds for aberrations in advanced stage samples were genome-wide higher than for the early stage samples (see supplementary materials for details). Weighted unsupervised clustering of called array CGH data was performed as described previously [21, 22]. Clusters found were correlated to overall and progression free survival using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log rank testing (SPSS software package version 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA). All other analyses were performed in the statistical framework R [23].

Results

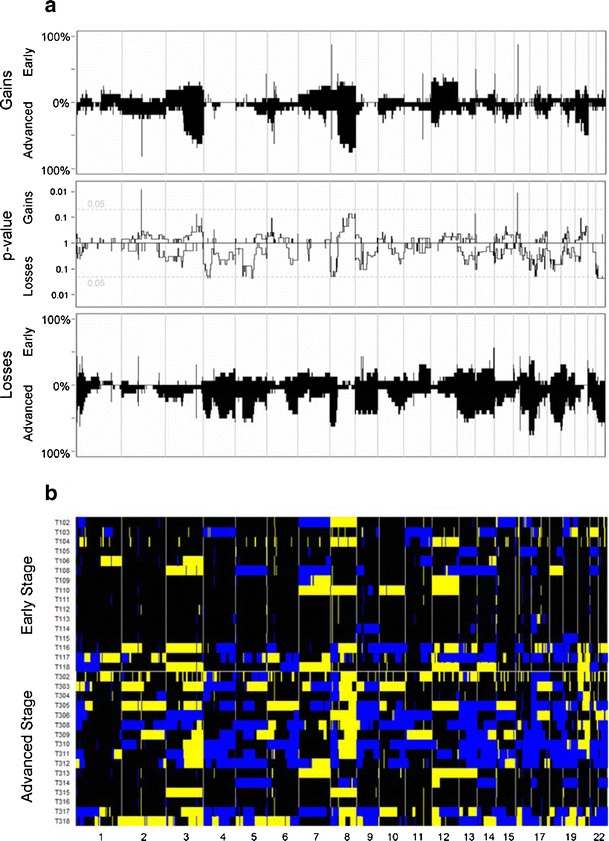

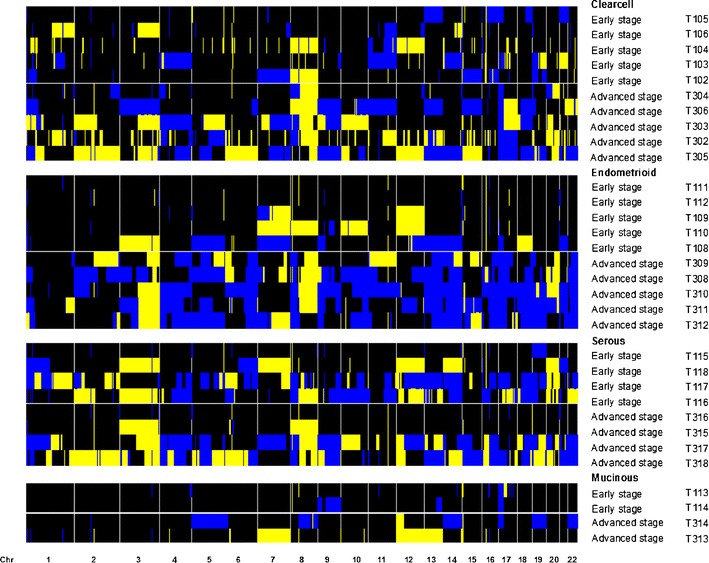

The patterns of aberrations in the advanced stage group mirrored those in the early stage group. Moreover, virtually all of the genomic aberrations were more frequent in the advanced stage group (Fig. 1a); the odds for aberrations were genome-wide significantly (p = 0.012 higher in advanced stage ovarian cancer than in early stage disease (See supplementary materials for details). When compared on patient level (Fig. 1b) the tumor profiles are heterogeneous. However, when stratified per FIGO stage according to histological subtype (Fig. 2) the profiles display more similarity. Furthermore, Fig. 2 shows that progression of aberrations is most pronounced in the clearcell and endometrioid subtypes.

Fig. 1.

The frequencies of copy number gains in 16 early and 16 advanced stage ovarian cancer samples are plotted at the top of Panel A. The frequencies were tested for a difference between both stages and the false discovery rate corrected p-value is displayed. At the bottom of Panel A the analogue is shown for copy number losses. Panel B shows the array CGH profiles of all samples grouped per stage with blue indicating a loss, black a normal and yellow a gain in DNA copy number

Fig. 2.

Array CGH profiles ordered per histological type and FIGO stage. Blue indicates a loss, black a normal and yellow a gain in DNA copy number

When analysing the clinical and pathological characteristics of the tumors, we found the survival rate in patients with advanced stage ovarian cancer to be significantly lower than in patients with early stage cancer (p < 0.001), as expected. Contrastingly, stratification of the samples according to histological subtype yielded no significant difference in survival. However, patients with well-differentiated (grade one) tumors had significantly better survival than patients with intermediate and poorly (grades two and three) differentiated tumors combined (p = 0.044).

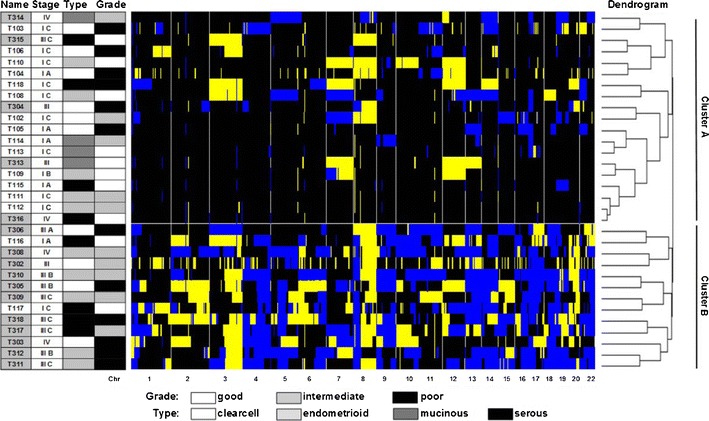

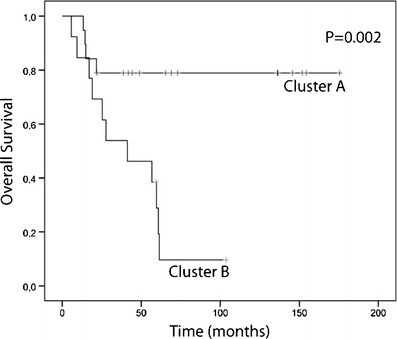

In order to study if and how aberrations correlate to the clinical behaviour of the tumors, weighted clustering of called array CGH data was performed and yielded two distinct groups of 19 tumor samples in cluster A and 13 in cluster B (Fig. 3). Cluster A contained 5 advanced and 14 early stage tumors, of which four and two, respectively had a recurrence. Cluster B contained 11 advanced and two early stage tumors of which ten and one, respectively had a recurrence (Pearson Chi-square for distribution of FIGO stage between the clusters p = 0.001). With a mean survival of 142.0 months (95 %CI 112.7–171.2), patients in cluster A had a significantly (Mantel Cox log rank p = 0.002) better survival than patients in cluster B (43.0 months, 95 %CI 27.4–58.6) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Heatmap of unsupervised clustering. Blue indicates a loss, black a normal, and yellow a gain in DNA copy number. The dendrogram on the right shows the similarity between the array CGH profiles. Left of the heatmap the tumor characteristics (FIGO stage, histological type and tumor differentiation grade) are displayed. A partition of the 32 ovarian cancer patients in cluster A and cluster B is found. In cluster A samples T104, T110, T304, T313, T314 and T316 had progression. In cluster B samples T117, T302, T303, T305, T308, T309, T310, T311, T312, T317 and T318 had progression

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier plot based on cluster A (n = 19) and cluster B (n = 13) identified by unsupervised clustering of array CGH data. The p-value was calculated using the Mantel-Cox log rank test

Discussion

Early and advanced stage ovarian carcinomas were compared with respect to chromosomal copy number aberrations measured by array CGH. Due to their distinct clinical presentation, we hypothesised that early and advanced stage ovarian cancer develop through separate molecular pathways. Aberrations were more frequent in advanced stage and there were virtually no aberrations in early stage that were not found in advanced stage. This finding suggests that advanced stage disease either progresses from early stage disease or from a common precursor lesion. This validates earlier findings in an independent data set using low resolution array CGH [6].

Unsupervised clustering of genomic aberrations significantly discriminated early from advanced stage samples. However, to differentiate molecular subtypes based on array CGH data, independent and high-resolution validation studies are necessary.

Depending on the scoring criteria, microsatellite instability (MSI) has been reported in 0–24 % of ovarian cancers [24–26], and little is known about their biological and clinical significance. However we did not test for MSI, so we can not exclude that in our samples there is MSI that could have influenced the outcome.

Ovarian carcinomas have been divided into subtypes by Shih and Kurman. [27] They propose a stratification based on clinical and histological characteristics in type I and type II tumors. Type I tumors are less frequent and are believed to be slow growing, generally confined to the ovary at diagnosis and genetically relatively stable. Histologically, type I tumors would consist of low-grade micropapillary serous carcinoma, mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell carcinomas and would be associated with mutations in KRAS, BRAF, PTEN, and beta-catenin. Type II tumors would form the most common type of ovarian carcinomas and are rapidly growing, highly aggressive and genetically unstable. They would be high-grade serous carcinoma, malignant mixed mesodermal tumors and undifferentiated carcinomas and are associated with TP53 mutations. As our study is based on FIGO stage 1 tumours we cannot compare cluster A and B with type I and II. However, we show that our study population (mainly consisting of type I tumours) can be further subdivided by array CGH into patients with good and poor overall survival.

The survival times differed significantly between both clusters. This finding suggests that the comparative genomic hybridization data of an ovarian carcinoma has the potency of being of clinical value in the future.

In conclusion, in this study we showed advanced stage ovarian cancer either progresses from early stage disease or from a common precursor lesion. We reject the hypothesis that the two stages might develop through distinct carcinogenic molecular events. Furthermore, when we divided patients in two groups solely on their genomic aberrations, we found these groups to differ significantly in survival. Since copy number analysis can be performed on easy to gain pre-treatment FFPE ovarian cancer tissue, array CGH data has the potency to identify patients with a worse prognosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Online supporting information

Raw data of all the arrays performed are publicly available in the GEO database (accession number GSE24418).

Details of the statistics to test whether odds for aberrations in advanced stage ovarian cancer are genome wide higher than in early stage. (JPEG 597 kb)

Plots of the normalized and de-waved data with segmentation and calls of individual tumor samples. The blue lines represent the segments, the green bars the gains and the red bars the losses. The length of the bars represent the probability of the call. For the further analysis, calls were used with a probability of more than 50 %. The blue dots at the top of the figures indicate amplifications. These amplifications are handled as gains in the consecutive analysis. Balancing between the readability and accuracy of this Figure, we have used a lower resolution than in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Therefore, some small aberrations seen in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 are not seen in this Figure. (PNG 4080 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was partly financed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC, trial number 55904). We would hereby like to thank all women, investigators and their data managers who participated in the EORTC ACTION trial. Furthermore, we acknowledge Paul P. Eijk, Josien Haan, Daniëlle Israeli, Alan Mrsić, François Rustenburg and Serge J. Smeets (VU University Medical Center, Department of Pathology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for their technical and laboratory support.

Ethical standards

This research complies with the current Dutch legislation for academic medial research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

Afra Zaal and Wouter J. Peyrot contributed equally to this paper.

Contributor Information

Afra Zaal, Phone: +31-88-7556427, FAX: +31-88-7555433, Email: a.zaal@umcutrecht.nl.

P. M. J. J. Berns, Phone: +32-27-741611

Maria E. L. van der Burg, Phone: +31-10-7044370

J. Baptist Trimbos, Phone: +31-71-5262845.

Isabelle Cadron, Phone: +32-16-342642.

Paul J. van Diest, Phone: +31-88-7556565

Wessel N. van Wieringen, Phone: +31-20-4441047

Oscar Krijgsman, Phone: +31-20-4444852.

Jurgen M. J. Piek, Phone: +31-64-4474099

Petra J. Timmers, Phone: +31-10-2913381, Email: TimmersP@Maasstadziekenhuis.nl

References

- 1.Akeson M, Jakobsen AM, Zetterqvist BM, Holmberg E, Brannstrom M, Horvath G. A population-based 5-year cohort study including all cases of epithelial ovarian cancer in western Sweden: 10-year survival and prognostic factors. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2009;19:116–123. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181991b13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR, Jr, Wang SJ. Conditional survival in ovarian cancer: results from the SEER dataset 1988–2001. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;109:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aunoble B, Sanches R, Didier E, Bignon YJ. Major oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes involved in epithelial ovarian cancer (review) Int. J. Oncol. 2000;16:567–576. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauptmann S, Denkert C, Koch I, Petersen S, Schluns K, Reles A, Dietel M, Petersen I. Genetic alterations in epithelial ovarian tumors analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization. Hum. Pathol. 2002;33:632–641. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piek JM, Kenemans P, Verheijen RH. Intraperitoneal serous adenocarcinoma: a critical appraisal of three hypotheses on its cause. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:718–732. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shridhar V, Lee J, Pandita A, Iturria S, Avula R, Staub J, Morrissey M, Calhoun E, Sen A, Kalli K, Keeney G, Roche P, Cliby W, Lu K, Schmandt R, Mills GB, Bast RC, Jr, James CD, Couch FJ, Hartmann LC, Lillie J, Smith DI. Genetic analysis of early- versus late-stage ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5895–5904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brosens RP, Haan JC, Carvalho B, Rustenburg F, Grabsch H, Quirke P, Engel AF, Cuesta MA, Maughan N, Flens M, Meijer GA, Ylstra B. Candidate driver genes in focal chromosomal aberrations of stage II colon cancer. J. Pathol. 2010;221:411–424. doi: 10.1002/path.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S.J. Smeets, U. Harjes, W.N. van Wieringen, D. Sie, R.H. Brakenhoff, G.A. Meijer, B. Ylstra, To DNA or not to DNA? That is the question, when it comes to molecular subtyping for the clinic! Clin Cancer Res (2011) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, Vermorken JB, Mangioni C, Madronal C, Franchi M, Tateo S, Zanetta G, Scarfone G, Giurgea L, Timmers P, Coens C, Pecorelli S. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:113–125. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.B. Trimbos, P. Timmers, S. Pecorelli, C. Coens, K. Ven, B.M. van der, A. Casado, Surgical staging and treatment of early ovarian cancer: Long-term analysis from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.L. Verleye, P.B. Ottevanger, G.B. Kristensen, T. Ehlen, N. Johnson, M.E. van der Burg, N.S. Reed, R.H. Verheijen, K.N. Gaarenstroom, B. Mosgaard, J.M. Seoane, d. van, V, R. Lotocki, G.W. van der, B. Penninckx, C. Coens, G. Stuart, I. Vergote, Quality of pathology reports for advanced ovarian cancer: Are we missing essential information? An audit of 479 pathology reports from the EORTC-GCG 55971/NCIC-CTG OV13 neoadjuvant trial. Eur J Cancer (2010) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Weiss MM, Hermsen MA, Meijer GA, van Grieken NC, Baak JP, Kuipers EJ, van Diest PJ. Comparative genomic hybridisation. Mol. Pathol. 1999;52:243–251. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.5.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buffart TE, Israeli D, Tijssen M, Vosse SJ, Mrsic A, Meijer GA, Ylstra B. Across array comparative genomic hybridization: a strategy to reduce reference channel hybridizations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:994–1004. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buffart TE, Tijssen M, Krugers T, Carvalho B, Smeets SJ, Brakenhoff RH, Grabsch H, Meijer GA, Sadowski HB, Ylstra B. DNA quality assessment for array CGH by isothermal whole genome amplification. Cell. Oncol. 2007;29:351–359. doi: 10.1155/2007/709290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Wiel MA, Brosens R, Eilers PH, Kumps C, Meijer GA, Menten B, Sistermans E, Speleman F, Timmerman ME, Ylstra B. Smoothing waves in array CGH tumor profiles. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Wiel MA, Kim KI, Vosse SJ, van Wieringen WN, Wilting SM, Ylstra B. CGHcall: calling aberrations for array CGH tumor profiles. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:892–894. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Wiel MA, van Wieringen WN. CGHregions: dimension reduction for array CGH data with minimal information loss. Cancer Informat. 2007;3:55–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Wiel MA, Smeets SJ, Brakenhoff RH, Ylstra B. CGHMultiArray: exact P-values for multi-array comparative genomic hybridization data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3193–3194. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheinin I, Ferreira JA, Knuutila S, Meijer GA, van de Wiel MA, Ylstra B. CGHpower: exploring sample size calculations for chromosomal copy number experiments. BMC Bioinforma. 2010;11:331. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilting SM, Smeets SJ, Snijders PJ, van Wieringen WN, van de Wiel MA, Meijer GA, Ylstra B, Leemans CR, Meijer CJ, Brakenhoff RH, Braakhuis BJ, Steenbergen RD. Genomic profiling identifies common HPV-associated chromosomal alterations in squamous cell carcinomas of cervix and head and neck1. BMC Med. Genom. 2009;2:32. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wieringen WN, van de Wiel MA, Ylstra B. Weighted clustering of called array CGH data. Biostatistics. 2008;9:484–500. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Development Core Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Ref Type: Generic (2009)

- 24.Geisler JP, Goodheart MJ, Sood AK, Holmes RJ, Hatterman-Zogg MA, Buller RE. Mismatch repair gene expression defects contribute to microsatellite instability in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2199–2206. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helleman J, van Staveren I, Dinjens WN, van Kuijk PF, Ritstier K, Ewing PC, van der Burg ME, Stoter G, Berns EM. Mismatch repair and treatment resistance in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plisiecka-Halasa J, nsonka-Mieszkowska A, Kraszewska E, nska-Bidzinska A, Kupryjanczyk J. Loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite instability and TP53 gene status in ovarian carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:989–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shih IM, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63708-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of the statistics to test whether odds for aberrations in advanced stage ovarian cancer are genome wide higher than in early stage. (JPEG 597 kb)

Plots of the normalized and de-waved data with segmentation and calls of individual tumor samples. The blue lines represent the segments, the green bars the gains and the red bars the losses. The length of the bars represent the probability of the call. For the further analysis, calls were used with a probability of more than 50 %. The blue dots at the top of the figures indicate amplifications. These amplifications are handled as gains in the consecutive analysis. Balancing between the readability and accuracy of this Figure, we have used a lower resolution than in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Therefore, some small aberrations seen in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 are not seen in this Figure. (PNG 4080 kb)