Abstract

New cyanobacterial expression vectors, possessing an origin of replication that functions in a broad range of Gram-negative bacteria, were constructed. To inspect the shuttle vectors, the gene gfp was cloned downstream from the expression control element (ECE) originating from the regulatory region of the Microcystis aeruginosa gene psbA2 (for photosystem II D1 protein), and the vectors were introduced into three kinds of cyanobacteria (Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, and Limnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. ABRG5-3) by conjugation. Multiple copy numbers of the expression vectors (in the range of 14–25 copies per cell) and a high expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) at the RNA/protein level were observed in the cyanobacterial transconjugants. Importantly, GFP was observed in a supernatant from the autolysed transconjugants of ABRG5-3 and easily collected from the supernatant without centrifugation and/or further cell lysis. These results indicate the vectors together with the recombinant cells to be useful for overproducing and recovering target gene products from cyanobacteria.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00253-012-3989-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: AU-box sequence, Auto cell lysis cyanobacteria, Conjugation, Expression vector, Light-responsive psbA promoter

Introduction

Cyanobacteria are photosynthesizing eubacteria that make good models for basic research on photosynthesis and applied biotechnology for the production of carbohydrates, photosynthetic pigments, and other natural products. Microcystis aeruginosa strain K-81 (Shirai et al. 1989) and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 are Gram-negative non-nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria and can perform oxygenic photosynthesis. Light-responsive transcripts of the gene psbA2 (for photosystem II D1 protein) or their molecular structures have been characterized in unicellular cells of K-81 and PCC 6803 (Asayama et al. 2002; Imamura et al. 2003; Imamura and Asayama 2009; Sato et al. 1996). Moreover, light-responsive K-81 psbA2 transcripts have also been well studied in heterologous cells of bacillary Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 (Ito et al. 2003; Shibato et al. 2002).

Gene cloning and transfer are indispensable for cyanobacterial genetic manipulations. In cyanobacteria, possible transformation methods include natural transfer, the electroporation of extraneous DNA, and the transfer of foreign DNA by bacterial conjugation (Golden et al. 1987; Heidorn et al. 2011; Kuhlemeier and van Arkel 1987; Marraccini et al. 1993; Simon 1984; Thiel 1994; Thiel and Wolk 1987). The efficiency of the transformation depends on the donor DNA form and on the competency of the cyanobacterial recipient cells and, as well as in conjugation, on the restriction–modification barriers of the cells (Takahashi et al. 1996). Furthermore, the transferred DNA is classified by fate. One approach is the integration of foreign DNA into the cyanobacterial chromosome. In this case, autonomously replicating plasmids of cyanobacteria cannot be employed, and linearized or circular DNA is generally used during natural transfer and electroporation for the integration into a chromosomal target site via double or single crossover reactions, respectively (Chauvat et al. 1986; Xu et al. 2011). An alternative is the use of a shuttle vector (as Escherichia coli–cyanobacteria) which can autonomously replicate in the cytoplasmic space of cyanobacterial cells. In this case, mobilization of the plasmid DNA into the cells is generally performed by conjugation. Since DNA uptake in strain PCC 6803 has been known to be associated with the conversion of double-stranded molecules into single-stranded ones and a low efficiency/high rate of mutagenesis during transformation by electroporation (Barten and Hill 1995), conjugative transfer might be a convenient method in the cyanobacterium.

Vectors mobilized by conjugation into cyanobacteria are categorized by their replicons into two kinds. The first type contains the replication origin of the ColE1-type pMB1 plasmid of narrow E. coli host range (Thiel 1994); the transfer of plasmids of this type into cyanobacteria is ensured by conjugative plasmids of the IncP group in the presence of the ColK plasmid (Wolk et al. 1984). The second type was constructed on the basis of the replicon from the RSF1010 plasmid belonging to the IncQ group. Plasmids of this kind are able to replicate in a broad range of Gram-negative bacteria, including cyanobacteria and E. coli (Kreps et al. 1990). Because IncQ plasmids are of medium size (∼10 kb) with a large replicon, have multiple copy numbers (∼10 to 30 per cell; Huang et al. 2010; Marraccini et al. 1993; Ng et al. 2000; Rawlings and Tietze 2001), and are easy to mobilize (Barth and Grinter 1974; Guerry et al. 1974; Meyer et al. 1982), their use in genetic studies of cyanobacteria seems to be favorable.

Attention has been given to the development and evaluation of expression vectors which can replicate and maintain multiple copies (Elhai et al. 1997; Huang et al. 2010). Here, new cyanobacterial expression vectors were constructed with the expression control element (ECE) of the M. aeruginosa K-81 psbA2 regulatory region and the origin of replication from IncQ plasmid pVZ321, an RSF1010-based shuttle vector (Zinchenko et al. 1999). In this study, a gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) was cloned downstream from the ECE and introduced into the unicellular, bacillary, and filamentous cells of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, S. elongatus PCC 7942, and Lymnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. ABRG5-3, respectively. Systematic analyses revealed multiple copy numbers of the vectors in the cells and abundant expression of GFP at the transcriptional and translational levels. Based on the results, the overproduction using autolysed cyanobacteria of target gene products useful to the biotech industry is discussed.

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and plasmids

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Kazusa DNA Research Institute), S. elongatus PCC7942, or Lymnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. ABRG5-3 cells were grown on CB or BG11 plates or in liquid medium (Allen 1968; Rippka 1988; Shirai et al. 1989) at 30 °C, supplemented with 2.5 or 8 μg ml−1 of chloramphenicol as required. All routine plasmid constructions and cloning in E. coli were done as described (Sambrook and Russell 2000).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains or plasmids | Genotype, phenotype and other characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | F-endA1 supE44 λ-thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 | Cosmo Bio |

| DH5αMCR | deoRΔ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | (Tokyo, Japan) |

| Escherichia coli | E. coli B F − ompT hsdS (r−B m−B) dcm + | Stratagene |

| BL21-CodonPlus | gal λ (DE3) endA The [argU ileY leuW CmR], TetR | (North Torrey Pines RoadLa Jolla, USA) |

| (DE3)-RIL | ||

| Synechocystis sp. | Wild type (WT) | Kazusa DNA |

| PCC 6803 | Research Institute | |

| 6803_pVZ321a | PCC6803 transconjugant with pVZ321 (CmR, KmR) | This study |

| 6803_GFP500 | PCC6803 transconjugant with pGFP500 (CmR) | This study |

| 6803_GFP461c | PCC6803 transconjugant with pGFP461c (CmR) | This study |

| Synechococcus elongatus | Wild type (WT) | Univ. of Tokyo |

| PCC 7942 | ||

| 7942_pVZ321 | PCC7942 transconjugant with pVZ321 (CmR, KmR) | This study |

| 7942_GFP500 | PCC7942 transconjugant with pGFP500 (CmR) | This study |

| 7942_GFP461c | PCC7942 transconjugant with pGFP461c (CmR) | This study |

| Limnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. | Wild type (WT) | Nishizawa et al. (2010) |

| ABRG5-3L1 | ||

| 5-3_pVZ321 | ABRG5-3 transconjugant with pVZ321 (CmR, KmR) | This study |

| 5-3_GFP500 | ABRG5-3 transconjugant with pGFP500 (CmR) | This study |

| 5-3_GFP461c | ABRG5-3 transconjugant with pGFP461c (CmR) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAG500 | pAM990 + M. aeruginosa K-81 psbA2 a | Agrawal et al. (1999) |

| -404/+113 (SmaI–BglII fragment, WT), ApR SpR | ||

| pAG461 | pAM990 + M. aeruginosa K-81 psbA2 | Agrawal et al. (2001) |

| −404/+113 (SmaI–BglII fragment, ΔAT), ApR SpR | ||

| pAD461c | pAM990 + M. aeruginosa K-81 psbA2 | This study |

| -404/+113 (SmaI–BglII fragment, ΔAT and a deletion of G at the position of +36), ApR SpR | ||

| pGLO | E. coli expression vector for gfp, ApR | Clontech (Mountain View, USA) |

| R751 | IncP Tra+, TpR | Meyer and Shapiro (1980) |

| pVZ321 | IncQ Mob+, KmR CmR | Zinchenko et al. (1999) |

| pAM500 | Cyanobacterial expression vector (pVZ321 + PpsbA2_WT), CmR | This study |

| pAM461c | Cyanobacterial expression vector (pVZ321 + PpsbA2_ΔAT), CmR | This study |

| pGFP500 | pAM500 + gfp derived from pGLO, CmR | This study |

| pGFP461c | pAM461c + gfp derived from pGLO, CmR | This study |

Conjugative transformation

Conjugation was done with the host cyanobacteria. E. coli strain DH5αMCR (Sambrook and Russell 2000) harbored the expression vector, and E. coli strain JM109 (Sambrook and Russell 2000) harbored the helper plasmid R751, as described previously (Zinchenko et al. 1999). The cyanobacterial transconjugants were selected on CB or BG11 plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (8 μg ml−1 for PCC 6803 and ABRG5-3, 2.5 μg ml−1 for PCC 7942) or kanamycin (15 μg ml−1) under conditions excluding the E. coli cells.

DNA, RNA, and protein techniques

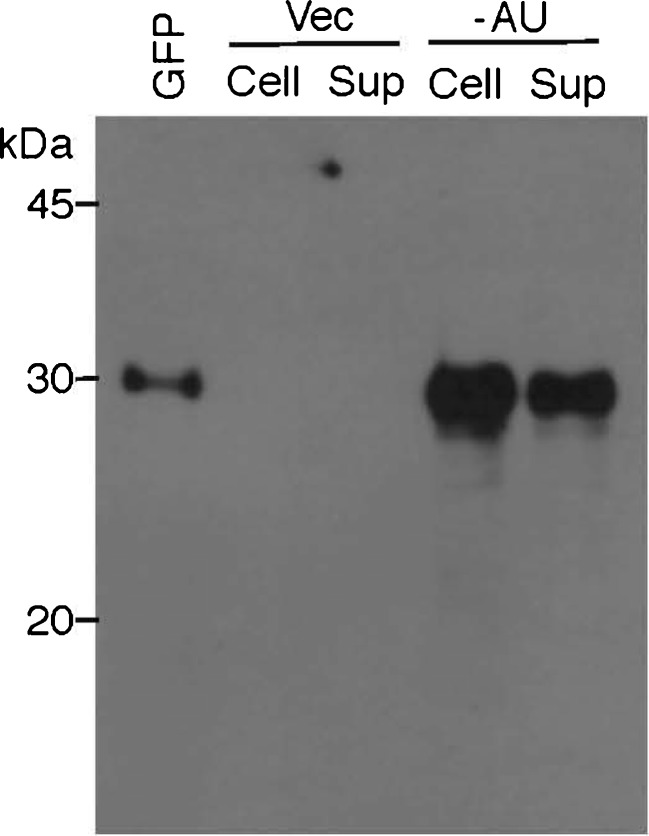

Genomic DNA and total RNA were prepared from cyanobacteria as described previously (Imamura et al. 2003). Gel electrophoreses, hybridization, and detection using ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) systems were reported elsewhere for Southern and Western blots (Imamura et al. 2003). Primer extension was performed as described previously (Asayama et al. 2004) with a specific primer, gloGFP-R (5′-GAATTGGGACAACTCCAGTG-3′). For protein recovery (Fig. 11), the naturally precipitated cell pellet of ABRG5-3 (100 μl) or the supernatant (10 ml) was collected from a screw-cap tube and poured into 50 ml of the cell culture, in which ABRG5-3 transconjugants harboring pVZ321 (Vec) or pGFP461c (−AU) were autolysed. The supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of saturated ammonium sulfate and subjected to centrifugation (13,500 rpm, 10 min) for the precipitation of GFP. The pellet containing GFP was dissolved with 50 μl of TE10-1 buffer (Sambrook and Russell 2000). Both fractions from the cell pellet (Cell, 100 μl) or the supernatant (Sup, 50 μl) were dissolved in an equal volume of ×2 SDS sample buffer and subjected to by heat treatment (95 °C, 3 min). Aliquots of respective protein fractions (25 μl) from the cell pellet or supernatant were then subjected to 12.5 % SDS-PAGE. The purification of control GFP from E. coli BL21 (Sambrook and Russell 2000) harboring pGLO (Clontech, Mountain View, USA) was carried out by a procedure with hydrophobic interaction chromatography (Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan). The GFP polyclonal antibody (rabbit antiserum) was purchased from MBL (Nagoya, Japan). The signal intensity corresponding to the target DNA, RNA (transcripts), or protein on X-ray film was measured with BIO-1D V. 96 software (Vilber Lourmat, Marne la Vallée, France) or a FLA7000 phosphoimager (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan; Asayama et al. 2004).

Fig. 11.

Western blot analysis for confirmation of overexpression and easy recovery of GFP from autolysed ABRG5-3 transconjugant cells. The ABRG5-3 transconjugants harboring pVZ321 (Vec) or pGFP461c (−AU) were grown in the CB medium under continuous white light illumination (100 μE m-2 s−1) at 30 °C with shaking (50 rpm) in Erlenmeyer flasks (50 ml of medium in a 300-ml flask exposed to 2 % CO2 gas) for 7 days. After this phase of cell growth for overproduction of GFP, the cell culture (50 ml) was poured into a screw-cap tube and allowed to stand for 3 days on a laboratory bench at room temperature for promoting auto-cell lysis. Cell sediment (100 μl) corresponding to the 50-ml cell culture or protein precipitate (50 μl) from the supernatant corresponding to 10 ml of the 50-ml culture (see details described in “Materials and methods”) was mixed with an equal volume of ×2 SDS sample buffer, then subjected to 12.5 % SDS-PAGE. The gel was also subjected to Western blot analysis with the GFP antibody as in Fig. 4. Purified GFP (29 kDa) protein (1 μg) was also applied as a size marker (left lane)

Measuring numbers of cells, plasmids, and proteins

The method used to count the cyanobacterial cells was described previously (Asayama et al. 2004; Shirai et al. 1989). For plasmids, the copy number was calculated by comparing the intensity of bands (at position 8.7 kbp) on original X-ray films referring to the samples and concentration markers in the Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2b). Values were expressed as a quota per cell number. For the calculation, we used the value for 70 % efficiency of cell disruption in hot phenol extraction to prepare total DNA (Asayama et al. 2004; Imamura et al. 2003). For proteins (Fig. 4b), the molecule number was also measured by comparing signal bands on original X-ray films referring to the samples and concentration markers (Asayama et al. 2004; Imamura et al. 2003). This value was also expressed as a quota per cell number. The value for 70 % efficiency of cell disruption by the glass–bead method employed to prepare total protein was used (Asayama et al. 2004; Imamura et al. 2003). Of note is that the intensity of signals was standardized using a FLA7000 phosphoimager.

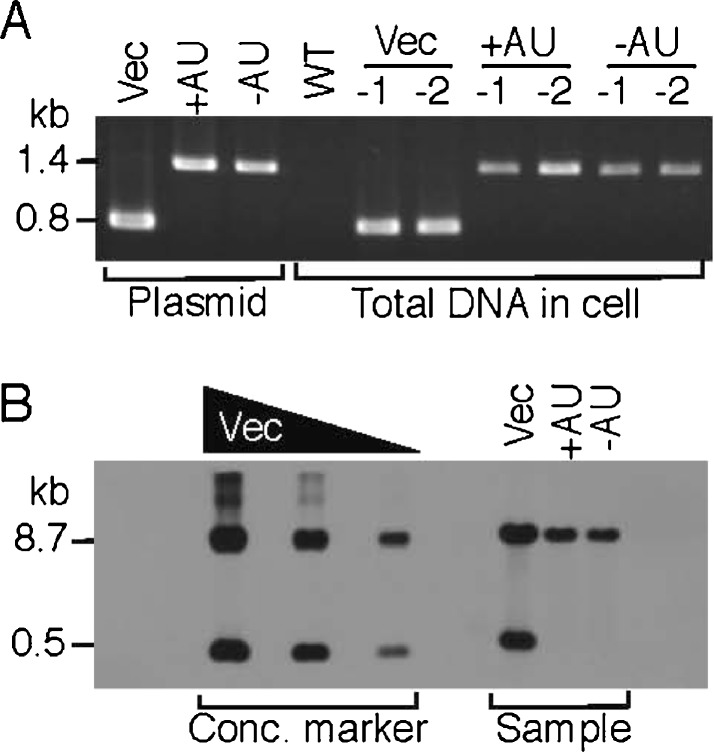

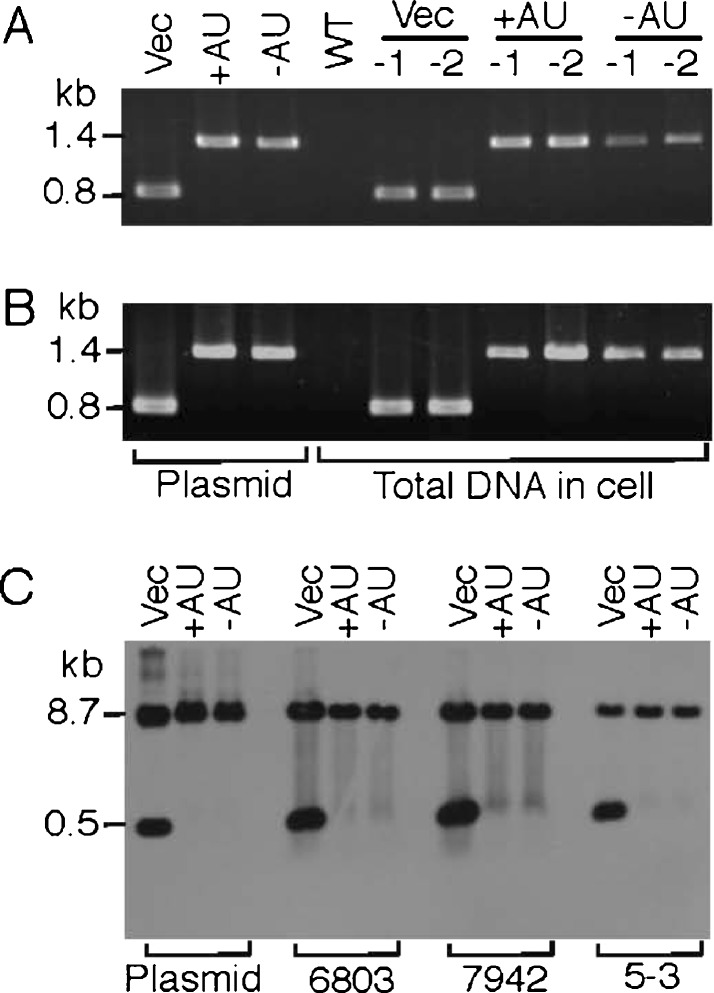

Fig. 2.

Analysis of PCC 6803 transconjugants containing GFP expression vectors. a PCR. Total DNA (1 μg) was isolated from the PCC6803 wild-type (WT) or recombinant cells conjugated with pVZ321 (Vec), pGFP500 (+AU), and pGFP4561c (−AU), respectively. Each two samples (−1 and −2) were subjected to PCR with a set of specific primers, VZ-F2 and VZ-R (Fig. 1). The 1.4- or 0.8-kb position for the PCR-amplified fragments from the pGFP500/461c or pVZ321 plasmid DNA is shown as a positive control at the left. b Southern blot analysis. Total DNA (20 μg) was isolated from the cells in (a), digested by the restriction enzymes HindIII and XhoI, and subjected to Southern hybridization with a specific probe (812 bp, a PCR-fragment amplified with pVZ321 and the primers VZ-F2 and VZ-R). The 8.7- or 0.5-kb position for the concentration marker is indicated at the left. The DNA of pVZ321 (left lane, 0.24 μg, 0.040 pmol; middle lane, 0.080 μg, 0.0133 pmol; right lane, 0.02 μg, 0.0033 pmol) digested with the same restriction enzymes was subjected to hybridization for the concentration marker which was used for a trial calculation of plasmid copy numbers in the cells (Table 2)

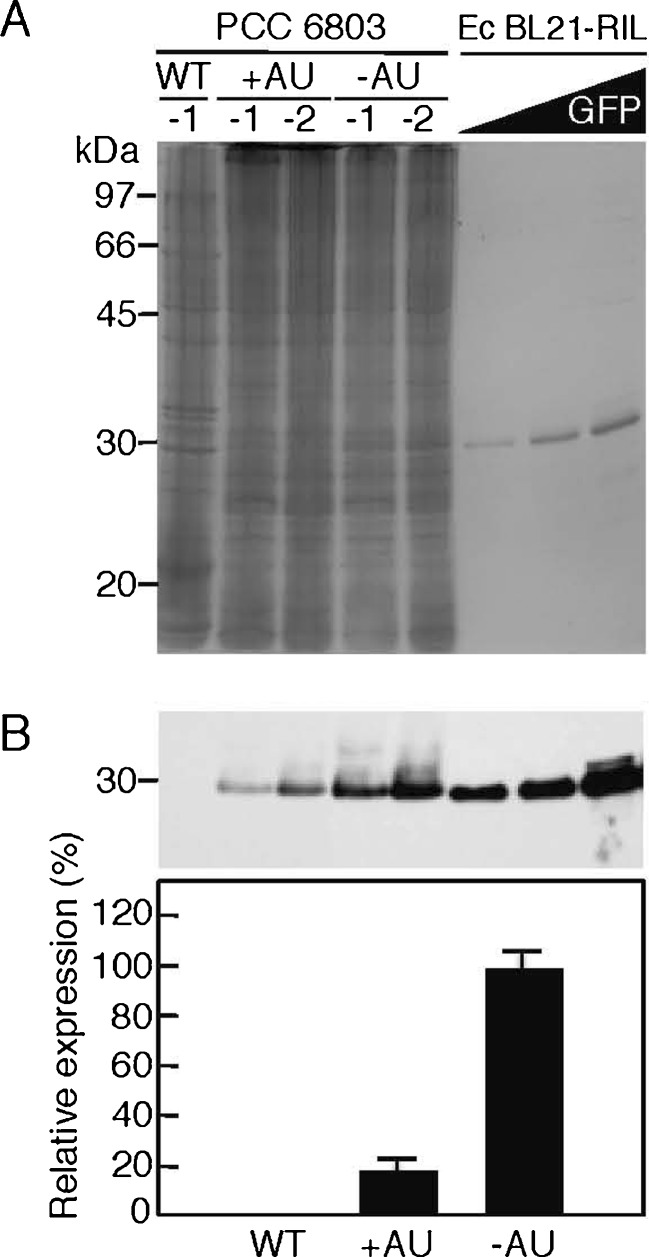

Fig. 4.

GFP expression at the protein level in PCC6803. a SDS-PAGE. Total cellular protein (40 μg) was prepared from wild-type (WT) Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 cells or cells harboring pGFP500 (+AU) or pGFP461c (−AU) grown in the CB medium for 12 days, then each two samples (−1 and −2) were subjected to 12.5 % SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Purified GFP (29 kDa) proteins (left lane, 1.45 μg, 50 pmol; middle lane, 2.90 μg, 100 pmol; right lane, 8.70 μg, 300 pmol) obtained from E. coli BL21 (RIL as codon plus) harboring pGLO were also applied as concentration markers. The positions (in kilodaltons) from a standard molecular size marker are shown at the left. b Western blot analysis. Top Aliquots of total cellular protein (40 μg) loaded from the samples shown in the different lanes in Fig. 4a in the same order were subjected to Western blotting with a specific antibody for GFP. The 30-kDa position is indicated at the left. Signal intensities corresponding to GFP on an X-ray film in the top panel were measured and presented as relative values (pVZ461c as 100 %) with error bars (n = 3, means ± SD)

Polymerase chain reactions

For the analysis of transcripts, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction/quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR/QRT-PCR) was done. Details for the preparation of total RNA and cDNA and the RT-PCR/QRT-PCR have been described previously (Asayama et al. 2004). The specific gfp primers used were: GFP-F primer, 5′-CATATGGCTAGCAAAGGAGAAGAA-3′ (24 mer); GFP-RT primer, 5′-TTTGTAGAGCTCATCCATGCCATG-3′ (24 mer); and GFP-QRT primer, 5′-GAGAAAGTAGTGACAAGTGTTG-3′). For the measurement of plasmid copy numbers, quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was also performed. Q-PCR was basically done the same as QRT-PCR with total DNA, prepared from the transconjugants harboring expression vectors and a set of specific primers, 6803rpoB-QF (5′-ATGACAAACCTTGCCACCACGATG-3′, 24 mer) and 6803rpoB-QR (5′-AGCATCCCGTCGCTTGGATTCATC-3′, 24 mer), for the gene rpoB (for the β-subunit of RNA polymerase) in the PCC 6803 genomic DNA or primers GFP-F and GFP-RT for the expression vectors.

Microscopic observation

The cyanobacterial cells grown in the CB or BG11 medium at 30 °C for 12 days were observed under an optical microscope (BX51/DP50, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence of chlorophyll/phycocyanin (red) or GFP-expressing (green) cells was detected using a U-MWIB2 filter for excitation (460–490 nm) and emission (510 nm; Nishizawa et al. 2010).

Results

Construction of cyanobacterial expression vectors carrying an ECE from the M. aeruginosa gene psbA2

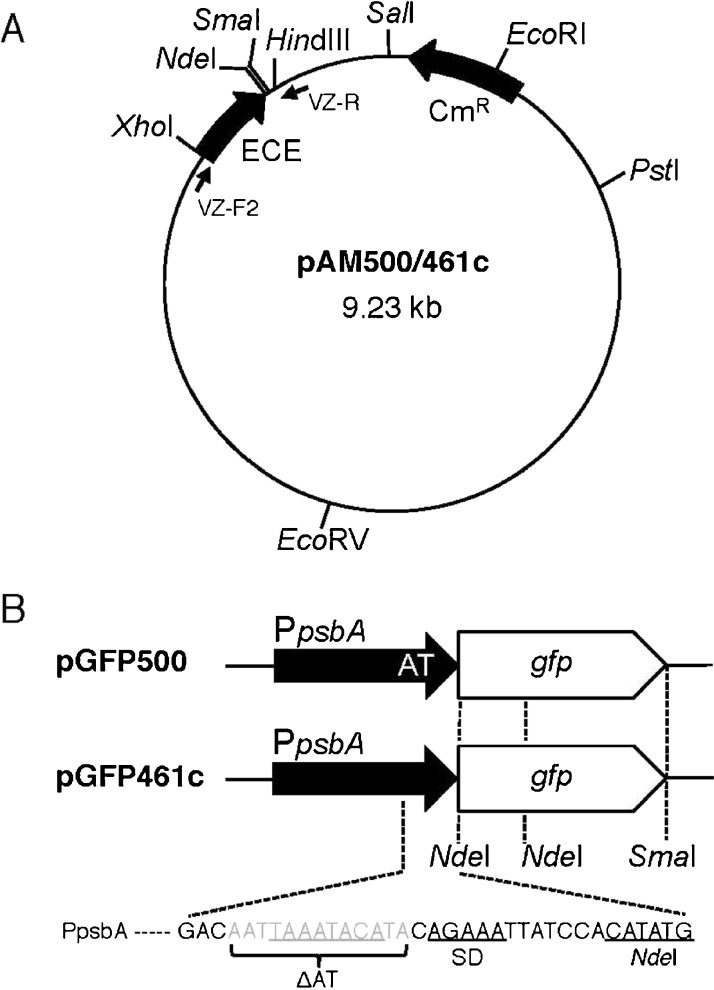

The promoter of psbA2 (PpsbA) and its ribosome-binding site of the cyanobacterium M. aeruginosa K-81 (Agrawal et al. 2001; Horie et al. 2007; Sato et al. 1996) were amplified by PCR using the primers K81psbA-404F_XhoI (5′-CCGCTCGAGGATCTCATAGAAACGATAAATC-3′, the site for XhoI shown in italics) and HY908-R_NdClSm&Hd (5′-CCCAAGCTTTTACTACCCGGGATCGTACATATGTGGATAATTTCTGC-3′, sites for HindIII, SmaI, ClaI, and NdeI shown in italics) from the plasmid pAG500 (wild-type K-81 psbA) or pAD461c (disruption of the AU-box for the light-dependent expression of psbA2 in the psbA2 5′-untranslated region; Agrawal et al. 2001) as the DNA template. The amplified elements were digested with XhoI and HindIII and introduced into the XhoI and HindIII sites of pVZ321, an RSF1010-based shuttle vector (Zinchenko et al. 1999), to make pAM500 or pAM461c (Fig. 1a). The NdeI and SmaI (or HindIII) sites were left available for target gene cloning into the pAM vectors. The pAM500 vector contains the light-responsive K-81 psbA2 promoter and its ribosomal binding site encompassing the AU-box sequence (Fig. 1b) which causes mRNA instability in darkness (Agrawal et al. 2001; Asayama 2006; Horie et al. 2007). In pAM461c, the AU-box sequence was removed to increase mRNA stability, and so the constitutive accumulation of mRNA for a target gene is feasible. In both vectors, the region corresponding to XhoI–HindIII (0.53 kb), which covers most of the kanamycin resistance gene on the original plasmid pVZ321, was consequently replaced with the element of M. aeruginosa psbA2 (0.5 kb), leaving a chloramphenicol resistance gene as a selective marker gene (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Expression vectors. a General structure. The plasmids contain as a regulatory region an expression control element (ECE) derived from the promoter of psbA2 (PpsbA) of the cyanobacterium M. aeruginosa K-81. The set of primers, VZ-F2 and VZ-R, for PCR is shown. b Vector for GFP expression. The GFP gene was introduced into the cloning sites of NdeI and SmaI to create pGFP500 (+AU) and pGFP461c (−AU). The AU-box nucleotide sequence (UAAAUACA) was deleted in pGFP461c for stable accumulation of the GFP mRNA. The nucleotides ATG at the NdeI site represent a start codon

Expression vectors for the overproduction of GFP

Although there are GFPs substituted at certain positions, F64L, S65T, or F64L + S65T (known as eGFP), for the enhancement of fluorescent strength in cells, a normal type of GFP gene was examined in this study (Cormack et al. 1996; Toyoshima et al. 2010; Yoon and Golden 1998). A NdeI–SmaI fragment of an Aequorea victoria GFP gene (717 bp, 239 aa—F64, S65) was prepared as follows. The plasmid DNA of pGLO carrying the GFP gene (from positions 1,343 to 2,059 in the plasmid) was digested with SmaI (at 1,080). It was then digested partially with NdeI (at 1,340 and 1,574) because one site of NdeI is located in the GFP gene (Fig. 1b). A 0.72-kbp fragment of NdeI–SmaI was isolated and then inserted into the NdeI and SmaI sites of pAM500 and pAM461c to create pGFP500 and pGFP461c, respectively (Fig. 1b). Nucleotide sequences of the region from XhoI to HindIII on respective plasmids were verified and these vectors were used for bacterial conjugation.

The GFP transconjugants and plasmid copy number in PCC 6803

The conjugation with pVZ321 (original vector), pGFP500 (wild-type K-81 psbA2, +AU), or pGFP461c (mutagenized K-81 psbA2, −AU) was conducted as described previously (see “Materials and methods”). Transconjugants of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 were obtained from the BG11 plates containing chloramphenicol and the presence of the vectors in the cells verified by PCR using the primers VZ-F2 (5′-CTGATGTTACATTGCACAAG-3′) and VZ-R (5′-ATGAAGGAGAAAACTCACCG-3′; Fig. 1a). We confirmed the presence of a 0.8-kb fragment for pVZ321 and a 1.4-kb fragment for pGFP500/461c in the PCR (Fig. 2a). We also verified the copy number of the vectors in the transconjugants (Fig. 2b). When total DNA was prepared from the cells harboring the vectors and Southern analysis was performed with the specific DNA probe (812 bp), which was amplified by PCR using the VZ-F2/-R primers and pVZ321, respective signals at the 0.53-kb (corresponding to a small XhoI–HindIII fragment carrying most of the kanamycin resistance gene in pVZ321) and/or 8.7-kb (corresponding to another large XhoI–HindIII fragment as the vector side) positions were observed on the X-ray film. The copy number of the plasmids was calculated based on the signal intensity at the 8.7-kb position in the Southern blot as follows (also see “Materials and methods”) since the 8.7-kb fragment is common among pVZ321 and its derivatives, pAM and pGFP. For example, the signal intensity from the gel indicated 0.004 pmol of pGFP500 (+AU) or pGFP461c (−AU). This accords with 24 × 108 molecules per lane. On the other hand, the total DNA (7.04 μl/20 μg/lane) prepared from the PCC 6803 transconjugants was subjected to Southern blotting. The volume of 7.04 μl accords with 2.46 ml of the PCC 6803 cell culture (7 × 107 cells per milliliter, Table 2) if the values are based on a 70 % efficiency of cell disruption (“Materials and methods”; Table 2). The culture of 2.46 ml accords with 1.72 × 108 cells per lane. Therefore, the copy number of pGFP plasmids is 14 molecules per cell (=24 × 108 molecules/1.72 × 108 cells). Following the same calculation procedure, the copy number of pVZ321 (Vec) was determined as 18 since the signal intensity from the gel accorded to 0.005 pmol (Table 2). IncQ-type plasmids derived from the RSF1010 replicon have been shown to have copy numbers in Synechocystis PCC 6803 ranging from 10 to 30 (or more higher) per cell (Huang et al. 2010; Marraccini et al. 1993; Ng et al. 2000; Rawlings and Tietze 2001). The replicative stability of the RSF1010 replicon depends upon its copy number and was shown to deteriorate when the copy number was lowered (Becker and Meyer 1997; Meyer 2009). Previous reports revealed that the number of PCC 6803 chromosomes was 12 per cell (Labarre et al. 1989). This number was used to create a link to plasmid copy numbers (plasmid number per chromosome number).

Table 2.

Vector copy numbers and GFP expression levels in cyanobacterial transconjugants

| Strain | Vector | Cma (μg ml−1) | Cell no.b (ml−1) | Vec. no.c (per cell) | GFP no.c (per cell) | GFP exp. (% per TCP) | Exp. rate ([GFP no.] [Vec. no.]−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCC 6803 | pVZ321 | 8 | 7 × 107 | 18 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| pGFP500 | 8 | 7 × 107 | 14 | 9.4 × 104 | 1 | 6.7 × 103 | |

| pGFP461c | 8 | 7 × 107 | 14 | 4.7 × 105 | 5 | 3.4 × 104 | |

| PCC 7942 | pVZ321 | 2.5 | 1 × 108 | 29 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| pGFP500 | 2.5 | 1 × 108 | 21 | 1.9 × 104 | 0.2 | 9.0 × 102 | |

| pGFP461c | 2.5 | 1 × 108 | 22 | 9.4 × 104 | 1 | 4.3 × 103 | |

| ABRG5-3 | pVZ321 | 8 | 8 × 107 | 16 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| pGFP500 | 8 | 8 × 107 | 15 | 2.0 × 104 | 0.2 | 1.3 × 103 | |

| pGFP461c | 8 | 8 × 107 | 15 | 1.0 × 105 | 1 | 6.7 × 103 |

exp. Expression, TCP total cellular protein, N.D. not detected

aCm, final concentration of chloramphenicol

bCell no., cell number (colonies from the cell culture were counted on a plate; see text)

cValues are based on a 70 % efficiency of cell disruption (see “Materials and methods”)

The copy number of pGFP carrying the gfp gene in the PCC 6803 cell was also confirmed by Q-PCR using the total DNA and a set of specific primers for gfp or rpoB, a single copy gene in the PCC 6803 chromosome (no other rpoB gene exists on the six kinds of endogenous plasmids in the cell; genome database, http://genome.kazusa.or.jp/cyanobase). The results indicated that the copy number of pGFP was 25 when the copy number of rpoB was 12 per PCC 6803 transconjugant (Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Fig. S1). This result did not contradict that of the Southern analysis mentioned above.

Analysis of light-responsive target gene expression from the vectors at the RNA level in PCC 6803

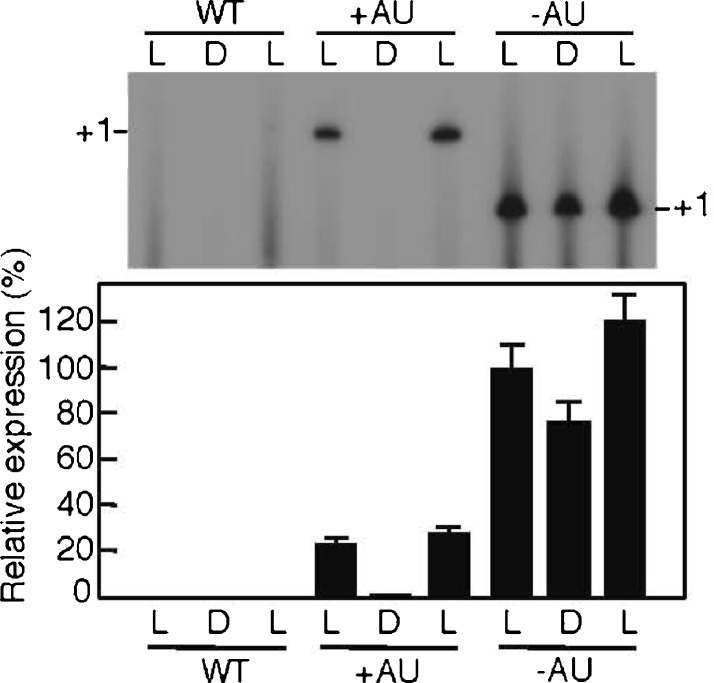

The accumulation of GFP transcripts from the expression vectors was examined by primer extension using the GFP-specific primer gloGFP-R. The results are shown in Fig. 3. When total RNA was prepared from the PCC 6803 cells harboring pGFP500 (+AU) and subjected to analysis, a clear pattern of light-responsive transcripts was observed under the light–dark–light (L–D–L) condition (Fig. 3, top; Agrawal et al. 2001; Asayama 2006; Horie et al. 2007). On the other hand, abundant GFP transcripts were observed in the PCC 6803 cells harboring pGFP461c even in darkness (Fig. 3, top). The position corresponding to the 5′-end (+1 as a transcription start point) of the GFP transcript shifted downstream 13 nt in the cells harboring pGFP461c, compared with that in the cells carrying pGFP500, since the AU-box sequence (13 bp in the pGFP461c; Fig. 1b) was deleted from the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of K-81 psbA2. The amount of the GFP transcripts from the cells harboring pGFP461c (−AU) was approximately five times higher than that from the cells harboring pGFP500 (+AU) under light (Fig. 3, bottom). This finding is in agreement with previous reports of the abundant accumulation of the K-81 mutagenized psbA2 (−AU) transcripts in transformants of S. elongatus PCC 7942 (Agrawal et al. 2001; Asayama 2006; Horie et al. 2007) and that the ECE is functional in the expression vectors at the RNA level.

Fig. 3.

GFP expression at the RNA level in PCC6803. The Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells of the wild type (WT) or transconjugants harboring pGFP500 (+AU) or pGFP461c (−AU) were grown under continuous white light (35 μE m-2 s−1) in the CB medium for 12 days, then exposed to a 12-h light (L)/12-h dark (D)/12-h light (L) cycle. The cells were harvested at specific times [3 h (L), 15 h (D), and 27 h (L)]. Total RNA (10 μg) was prepared from the cells and subjected to primer extension analysis with the 32P-end-labeled specific primer, gloGFP-R. Relative signal intensities (+1 as the transcription start point) on an X-ray film are presented for transcripts, with a 100 % value referring to that after 3 h of light in the GFP461c strain. Relative average values (in percent) are shown as bars with error values (standard deviation, SD) obtained from independent triplicate experiments

Overexpression of the target gene product at the protein level in PCC 6803

GFP expression was inspected at the protein level in the transconjugants (Fig. 4). When two fractions (−1 and −2) of total cellular protein were prepared from the cells and subjected to SDS-PAGE, bands were observed at the 29-kDa position (Fig. 4a). The intensity of the bands accounted for approximately 1 % and 5 % of total protein prepared from the cells harboring pGFP500 and pGFP461c, respectively. We further examined whether the bands were GFP proteins. We observed a signal at 29 kDa in the pGFP500 (+AU)- and pGFP461c (−AU)-harboring cells by Western blotting using the specific GFP polyclonal antibody, whereas there was no signal in the wild-type cells as a negative control, indicating that GFP was expressed in the transconjugants (Fig. 4b). The number of proteins was also calculated based on the signal intensity at the 29-kDa position in the Western blot as follows (also see “Materials and methods”). For example, the signal intensity from the gel indicated 69 pmol of GFP from pGFP461c (−AU)-harboring cells. This accords with 4.14 × 1013 molecules per lane. On the other hand, the total protein (20.4 μl/40 μg/lane) prepared from the PCC 6803 transconjugants carrying pGFP461c was subjected to Western blotting. The volume of 20.4 μl accords with 1.26 ml of the PCC 6803 cell culture (7 × 107 cells per milliliter; Table 2) if the values are based on a 70 % efficiency of cell disruption (“Materials and methods”; Table 2). The culture of 1.26 ml accords with 8.79 × 107 cells per lane. Therefore, the number of GFP molecules expressed in the PCC 6803_pGFP461c transconjugant is 4.7 × 105 per cell (=4.14 × 1013 molecules/8.79 × 107 cells). Using the same calculation procedure, the number expressed in the PCC 6803_pGFP500 transconjugant was determined as 9.4 × 104 since the signal intensity from the gel accorded with 13.8 pmol (Table 2). This value well coincided with the result in Fig. 3.

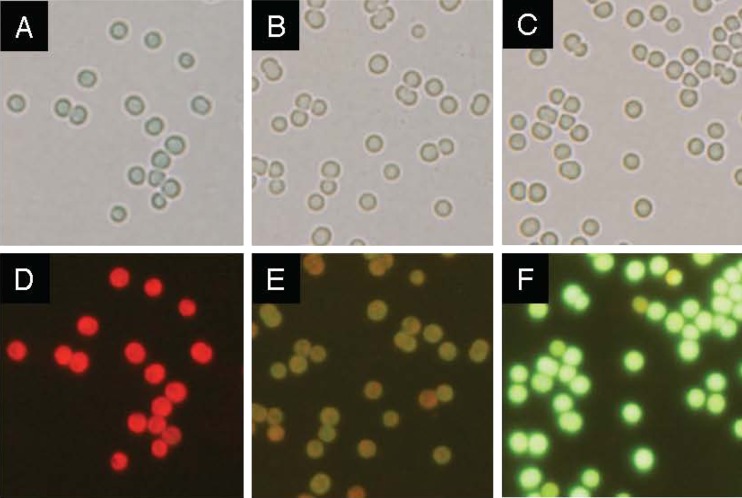

Microscopic observation for GFP overexpressed in PCC 6803 cells

Under the optical microscope, the shape and size appeared the same among the wild-type cells (Fig. 5a) and transconjugants (Fig. 5b, c). The transconjugants appeared slightly brown when grown in the CB medium supplemented with chloramphenicol. Fluorescent microscopic observation was conducted for the cells of the transconjugants. We observed browny green (panel e) and green (panel f) cells harboring pGFP500 and pGFP461c, respectively, against the red cells (panel d) of the wild type. This also showed significant GFP expression in transconjugants with the pGFP vectors.

Fig. 5.

GFP expression in PCC6803. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells were grown in the CB medium for 12 days. Wild-type cells (a), or cells harboring pGFP500 (b) or pGFP461c (c), were subjected to microscopic observation. Fluorescence of GFP was also observed in the wild-type cells (d), or cells harboring pGFP500 (e) or pGFP461c (f). The exposure time of all samples was 0.7 s

Stable expression of GFP in PCC 6803

To address the stable expression of GFP in PCC 6803 cells, transconjugants were cultivated with repetitive inoculation in which the cells were transferred every 3 weeks to new CB medium (8 μg ml−1 of chloramphenicol) in Erlenmeyer flasks for 12 months. The number of cells expressing GFP was almost the same during the period and the ratio (cells not expressing GFP/total transconjugants) very slightly decreased within 2.5–5 % in 6–12 months (Fig. 6). This suggests that the expression vectors had been constantly maintained in the PCC 6803 cells and that expression of GFP apparently occurred. Six and 12 months may correspond respectively to about 400–500 and 800–1,000 generations (Liu et al. 2011; Shen et al. 1993).

Fig. 6.

Stability of GFP expression over time in long-term cultures of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 transconjugants. The Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 transconjugants harboring pGFP500 (triangles) or pGFP461c (circles) were inoculated into Erlenmeyer flasks (1 %, v/v, in 50 ml of the CB medium, 110 rpm) at a regular interval of 3 weeks and continuously cultivated with the repetitive inoculation for 12 months. At 3, 6 (inset), and 12 months, the cells were harvested and again subjected to microscopic observation for fluorescence of GFP. For evaluation of GFP expression, five windows containing approximately 25–50 cells were randomly selected in the microscopic field, and the percentages for the numbers of green cells (expressed GFP) versus red cells (not expressing GFP, arrowhead) are shown as the stability of GFP expression. The line (triangles, circles) graph is presented with a 100 % value referring to that of the start of incubation (0 month, see Fig. 5e, f). Relative average values are shown as bars with error values (n = 5, means ± SD)

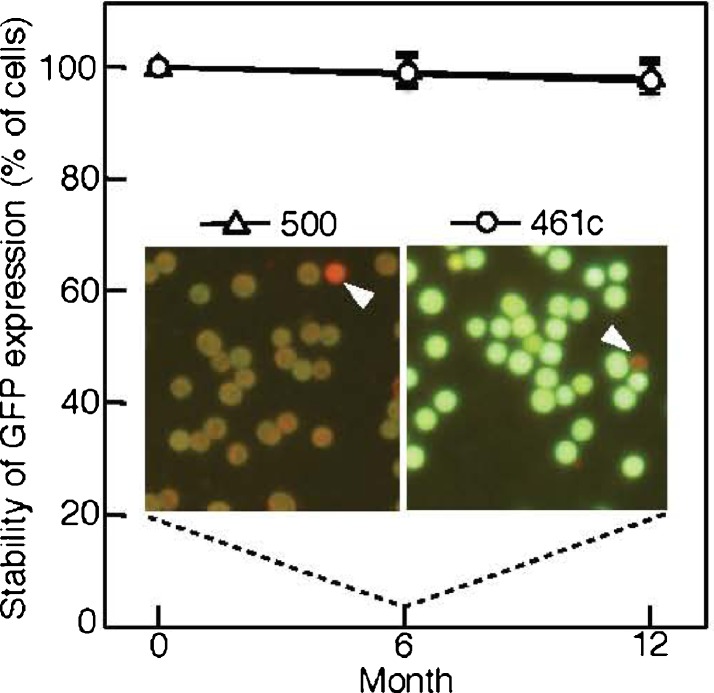

Medium’s effect on GFP expression

It was examined whether different levels of GFP expression occur in the PCC 6803 transconjugants grown in different media. The results are shown in Fig. 7. The cells harboring pVZ321 (the original vector, −GFP) appeared red when cultivated in both the BG11 (panel a) and CB (panel c) media and expressed no GFP. On the other hand, the cells harboring pGFP461c (+GFP) appeared orange when grown in the BG11 medium (panel b), but green when grown in the CB medium (panel d). The signal intensity corresponding to GFP prepared from the cells shown in panel b was actually lower than that in panel d when equal amounts of total protein were subjected to Western blotting (data not shown). These results show an effect of the medium and that GFP expression is apparently higher in the PCC 6803 cells grown in the CB medium than in the BG11 medium.

Fig. 7.

Medium’s effect on GFP expression. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells grown in the BG11 (a, b) or CB (c, d) medium for 12 days, harboring pVZ321 (a, c) or pGFP461c (b, e), were harvested into microtubes (top) and subjected to microscopic observation (bottom). Conditions were as for Fig. 5, but the exposure time was 0.5 s

The GFP transconjugants and plasmid copy number in PCC 7942 and ABRG5-3

Since the original pVZ plasmids have a broad host range in cyanobacteria (Zinchenko et al. 1999), it was examined whether the pAM expression vectors can be used in PCC 7942 as a bacillar and ABRG5-3 as a filamentous cyanobacterium (Nishizawa et al. 2010). The results in Fig. 8 show that plasmids pVZ321 (Vec), pGFP500 (+AU), and pGFP461c (−AU) were all maintained in the PCC 7942 and ABRG5-3 cells (panels a and b). It was also confirmed that multiple copy numbers of these expression vectors exist in PCC 7942 (Table 2). Although the expression vectors might also exist in multiple copy numbers in an ABRG5-3 transconjugant, the cell number per milliliter of the cell culture was calculated based on the number of colonies that appeared on CB medium after dilution of the cell culture. Since ABRG5-3 is a filamentous multicellular cyanobacterium, it was difficult to acquire an accurate cell number per milliliter of the cell culture (Nishizawa et al. 2010). Therefore, the estimated cell number described above was used for the calculation of plasmid copy numbers in the ABRG5-3 transconjugants. For example, the signal intensity from the gel indicated 0.002 pmol of pGFP500 (+AU) or pGFP461c (−AU). This accords with 12 × 108 molecules per lane. On the other hand, the total DNA (7.04 μl/20 μg/lane) prepared from the ABRG5-3 transconjugants was subjected to Southern blotting. The volume of 7.04 μl accords with 1 ml of the ABRG5-3 cell culture (8 × 107 cells per milliliter; Table 2) if the values are based on a 70 % efficiency of cell disruption (“Materials and methods”; Table 2). The 1 ml of culture accords with 8 × 107 cells per lane. The copy number of pGFP plasmids may be thus 15 molecules per cell (=12 × 108 molecules/8 × 107 cells). Following the same calculation procedure, the copy number of pVZ321 (Vec) was determined as 16 since the signal intensity from the gel accorded with 0.0021 pmol (Table 2).

Fig. 8.

PCR analysis of recombinant S. elongatus PCC 7942 (a) and Lymnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. ABRG5-3 (b) containing GFP expression vectors. Per strain, 1 μg of total DNA was analyzed by the same procedure as described in Fig. 2a. c Southern blot analysis of each expression vector’s copy number in PCC 7942 and ABRG5-3 transconjugants. The DNA of pVZ321 (Vec), pAM500 (+AU), and pAM461c (−AU) (left block, 0.0133 pmol) digested with the restriction enzymes HindIII and XhoI was subjected to hybridization with a specific probe as described in Fig. 2b for the concentration marker which was used for the trial calculation of plasmid copy numbers in the cells (Table 2). Total DNA (20 μg) was isolated from the respective transconjugants of PCC 6803, PCC 7942, and ABRG5-3, digested by the restriction enzymes, and also subjected to hybridization with the specific probe. Of note is that the exposure time for the X-ray film was approximately 1.5 times longer than that of Fig. 2b

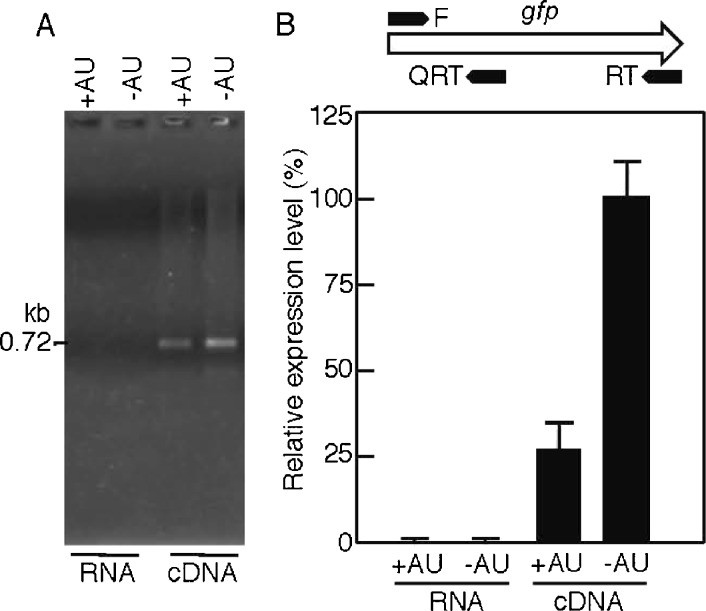

Analysis of the target gene expression at the RNA level in ABRG5-3

The accumulation of GFP transcripts in the transconjugants of ABRG5-3 was examined by PCR (Fig. 9). When total RNA was prepared from the cells harboring pGFP500 (+AU) and pGFP461c (−AU) and subjected to RT-PCR, no bands were observed, indicating the RNA template to be of appropriate quality and to contain no genomic DNA (panel a, left). Clear bands at the 0.72-kb position referring to the GFP transcript were observed when the cDNA samples were used in RT-PCR with the primers GFP-F and GFP-RT (panel a, right; panel b, top). This indicates that the GFP transcripts were expressed in the ABRG5-3 transconjugants. To confirm the precise amount of the GFP transcripts, we further conducted a QRT-PCR analysis using the cDNA (panel b). When GFP-F and GFP-QRT (panel b, top) were used, the apparent GFP transcripts were observed, and the amount of the GFP transcripts from the cells harboring pGFP461c (−AU) was approximately four times higher than that from the cells harboring pGFP500 (+AU) under light.

Fig. 9.

GFP expression at the RNA level in ABRG5-3 transconjugants. a RT-PCR. The ABRG5-3 transconjugants harboring pGFP500 (+AU) or pGFP461c (−AU) were grown under continuous white light illumination (35 μE m−2 s−1) in the BG11 medium for 12 days. The cells were harvested, total RNA (0.1 μg) without genomic DNA was prepared from the cells, and then cDNA (0.1 μg) was synthesized from the template RNA with the GFP-specific primer GFP-RT and reverse transcriptase. The RNA and cDNA were subjected to RT-PCR with the specific primers GFP-F and GFP-RT. The position of 0.72 kb for gfp is shown at the left. b QRT-PCR. The respective RNAs and cDNA were subjected to QRT-PCR with the GFP-specific primers GFP-F and GFP-QRT. The relative positions of each primer within the gfp gene are shown at the top. Details for the PCR were described previously (Asayama et al. 2004). Relative expression levels for transcripts were calculated with a 100 % value referring to that of cDNA in the GFP461c strain. Relative average values (in percent) are shown as bars with error values (standard deviation, SD) obtained from independent triplicate experiments

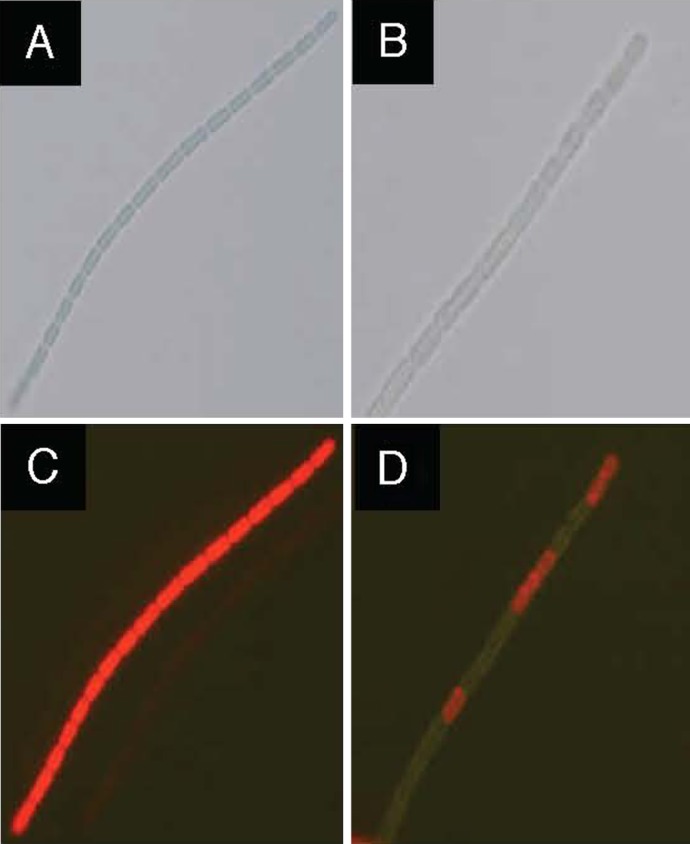

Microscopic observation for GFP overexpressed in the ABRG5-3 cells

Fluorescent microscopic observation was conducted in the ABRG5-3 cells (Fig. 10). It was confirmed that browny green (panel d) cells harbored pGFP461c against the glowing red cells (panel c) of the wild type. This also showed apparent GFP expression in the transconjugants harboring pGFP461c. The vivid red color (panel c) is unique to wild-type cells of ABRG5-3 and depends on an abundance of photosynthetic pigments (e.g. phycocyanin), as reported previously (Nishizawa et al. 2010). The abundant accumulation of photosynthic pigments according to the red cell color may hinder observations of the green color of GFP expressed in the transconjugants (panel d).

Fig. 10.

GFP expression in ABRG5-3 transconjugants. ABRG5-3 cells were grown in the CB medium for 12 days. Wild-type cells (a) or cells harboring pGFP461c (b) were subjected to microscopic observation. Fluorescence was also observed in the wild-type cells as a red color (c), or pGFP461c-harboring cells as a dark green/orange color (d) with a fluorescence microscope. Other details were as described for Fig. 5

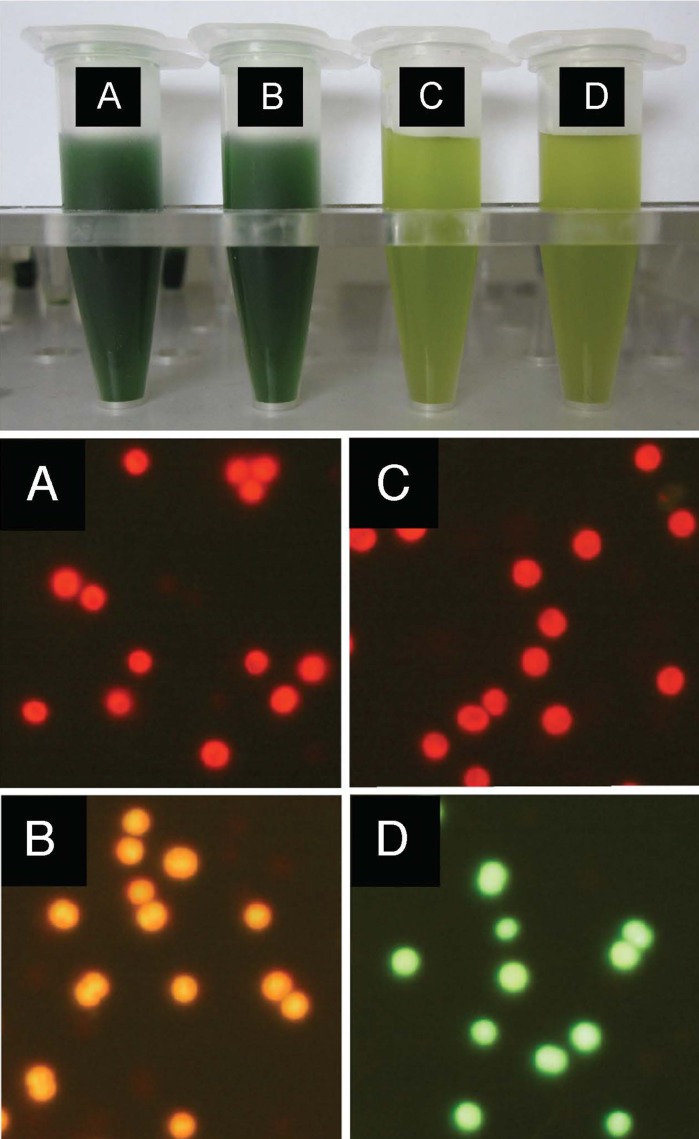

Easy recovery of overproduced GFP from autolysed ABRG5-3 cells

An attempt was made to recover the target gene product, GFP, from the supernatant of ABRG5-3 cells harboring pGFP461c (Fig. 11). It has been reported that auto-cell lysis occurs gradually (>50 % cells) within several days when ABRG5-3 cells are first subjected to liquid culture for cell growth and the accumulation of products and then exposed to static (standing) cultivation for auto-cell lysis (Nishizawa et al. 2010). In this study, GFP was shown to ooze into the supernatant (60 % of all cells autolysed) from the ABRG5-3 transconjugant harboring pGFP461c in the CB medium. Subsequently, the fractions of GFP (“Materials and methods”) collected from the cell (Cell, total GFP in 40 % of living cells) or the supernatant (Sup, total GFP in 60 % of autolysed cells) were subjected to Western blot analysis. The signal intensity for GFP from the gel accords with 3.2 × 1012 molecules per milliliter of the cell culture (as the remaining cell pellet, 40 %) or 4.8 × 1012 molecules per milliliter of the cell culture (as released into supernatant, 60 %). The total amount of GFP expressed in 5-3_pGFP461c was thus  molecules per milliliter of the cell culture. Therefore, the number of GFP molecules expressed in the 5-3_pGFP461c transconjugant is 1.0 × 105 per cell (=8 × 1012 molecules/8 × 107 cells). Using the same calculation, the number expressed in the 5-3_pGFP500 transconjugant was determined as 2.0 × 104 molecules per cell (Table 2). The analysis revealed that the supernatant from the autolysed cells harboring pGFP461c contains GFP molecules and that the GFP released was easily collected from the supernatant.

molecules per milliliter of the cell culture. Therefore, the number of GFP molecules expressed in the 5-3_pGFP461c transconjugant is 1.0 × 105 per cell (=8 × 1012 molecules/8 × 107 cells). Using the same calculation, the number expressed in the 5-3_pGFP500 transconjugant was determined as 2.0 × 104 molecules per cell (Table 2). The analysis revealed that the supernatant from the autolysed cells harboring pGFP461c contains GFP molecules and that the GFP released was easily collected from the supernatant.

Discussion

To my best knowledge, this is the first report including simultaneous analyses at the levels of DNA, RNA, and protein for a target gene, cloned into an expression vector, in photosynthesizing bacteria. In this study, the cyanobacterial psbA2-type promoter (PpsbA) and its encompassing region with the AT- (as AU- on RNA) box sequence from M. aeruginosa K-81 (Agrawal et al. 2001; Asayama 2006; Horie et al. 2007; Sato et al. 1996) were used for the expression control element (ECE) in two expression vectors, pAM500 and pAM461c. The expression of the target gene depends on the light conditions when transconjugants harbor pAM500 carrying the ECE of wild-type psbA2 (with AU-box, +AU). The usage of pAM500 with the light-controlled ECE seems, however, relatively limited since in many instances it would be more useful to manipulate cyanobacteria able to grow in the dark. Nevertheless, the wild-type PpsbA could be used for moderate gene expression that should be turned off during the night. This might be suitable for some restricted accumulation of a target gene product which is toxic in cyanobacteria since the overexpression of target proteins sometimes causes growth inhibition and/or results in inclusion body formation in host cells. On the other hand, the use of pAM461c with the ECE lacking the AU-box sequence (−AU) might be useful to overproduce target gene products under light and dark conditions. These two approaches confer an advantage or a variation for overexpression of the target gene in cyanobacteria.

Previous reports revealed that a shuttle vector, pARUB19, based on an endogenous Synechococcus plasmid and carrying a RuBisCO promoter, Prbc, and an ampicillin resistance marker could confer recombinant luciferase production at a level equivalent to 1.2 % of the total soluble protein in Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301 cells (Takeshima et al. 1994). In another report, a IncQ broad-host-range BioBrick shuttle vector, pPMQAK1, was constructed and derivatives with promoters (Ptrc, Prbc, Plac, Ptet, PR, and PrnpB) and a gfp gene were tested. Expression from the vectors in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, however, partially depended on the presence of a lac operator system derived from E. coli (Huang et al. 2010). Moreover, an integrative expression vector, pFPN, placed in the non-coding region of the genome of the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 was constructed with the strong light-inducible Anabaena promoter PpsbA1 by Chaurasia’s group (Chaurasia et al. 2008). The psbA1 promoter could drive expression from the subcloned gfp gene and GFP was observed in the cells. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 has also been reported to have regulated promoters: PpetJ (from the cytochrome c6 gene), which is repressed by copper (Tous et al. 2001), and PclpP (from a protease gene) and PrbpP (from an RNA-binding protein gene), which are responsible for the circadian regulation of bioluminescence production when inserted in a promoter-trap vector upstream of a luciferase gene (Aoki et al. 2002). The examples and data from this study show that various promoters are at hand for possible use as expression vectors.

The medium-related effects of fluorescence expression in this study were interesting and the use of the CB liquid medium rather than the BG11 liquid medium was more convenient in this study (Fig. 7). The reason for this is still unclear. The BG11 medium is relatively abundant in nitrogen added as sodium nitrate (Allen 1968; Rippka 1988). The nitrogen-rich medium allows the accumulation of photosynthetic pigments in cells, resulting in the brilliant blue-green color of the BG11 culture (Fig. 7, top, panels a and b versus. c and d) which relates to the strong red color as a background in the fluorescent microscopic observation. The CB medium was adjusted to pH 9.0, and thus more alkaline than the BG11 medium (pH 7.6) when the cells were inoculated for cultivation. How these differences in the composition of the culture medium influence microscopic observations and/or PpsbA function in the transformed cell remain to be elucidated (Mulo et al. 2009).

A filamentous and non-heterocystous cyanobacterium, Limnothrix/Pseudanabaena ABRG5-3, has been isolated (Nishizawa et al. 2010). This strain allowed transconjugation with pVZ321 and showed an abundant accumulation of pigments, easy recovery of nucleic acids, and autolysis of cells under static cultivation. The results in this study showed easy recovery of the non-secreted target gene product using the auto-cell lysis of ABRG5-3 transformed with an expression vector (Fig. 11). Since auto-cell lysis can be quite convenient for the easy recovery of overproduced materials without complicated cell destruction and centrifugation, we are trying to obtain transconjugants of ABRG5-3 overproducing value-added materials and to recover the products from the autolysed cells as a next step. Because the ability of cyanobacteria to photosynthesize is relatively high, it makes sense that CO2 gas is effectively fixed by photosynthesis in cyanobacteria producing high-value products, for example, pigments, carbohydrates, and fuels (Ducat et al. 2011).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 52 kb)

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Anzai for pGLO, and Dr. Nishizawa and Dr. Ohta for the microscopic observations. This work was supported in a part by scientific grants from IBARAKI University and PRESTO (SAKIGAKE project) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- Agrawal GK, Asayama M, Shirai M (1999) Light-dependent and rhythmic psbA transcripts in homologous/heterologous cyanabacterial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 255:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Agrawal GK, Kato H, Asayama M, Shirai M. An AU-box motif upstream of the SD-sequence of light-dependent psbA transcripts confers mRNA instability under darkness in cyanobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1835–1843. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. Simple conditions for growth of unicellular blue-green algae on plates. J Phycol. 1968;4:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1968.tb04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S, Kondo T, Ishiura M. A promoter-trap vector for clock-controlled genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;49:265–274. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama M. Regulatory system for light-responsive gene expression in photosynthesizing bacteria: cis-elements and trans-acting factors in transcription and post-transcription. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:565–573. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama M, Kato H, Shibato J, Shirai M, Ohyama T. The curved DNA structure in the 5′-upstream region of the light-responsive genes: its universality, binding factor and function for cyanobacterial psbA transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4658–4666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama M, Imamura S, Yoshihara S, Miyazaki A, Yoshida N, Sazuka T, Kaneko T, Ohara O, Tabata S, Osanai T, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Shirai M. SigC, the group 2 sigma factor of RNA polymerase, contributes to the late-stage gene expression and nitrogen promoter recognition in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:477–487. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barten R, Hill H. DNA uptake in naturally competent cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;129:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Barth PT, Grinter NJ. Comparison of the deoxyribonucleic acid molecular weights and homologies of plasmids conferring linked resistance to streptomycin and sulfonamides. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:618–630. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.2.618-630.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker EC, Meyer RJ. Acquisition of resistance genes by the IncQ plasmid R1162 is limited by its high copy number and lack of a partitioning mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5947–5950. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5947-5950.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasia AK, Parasnis A, Apte SK. An integrative expression vector for strain improvement and environmental applications of the nitrogen fixing cyanobacterium, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;73:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvat F, De Vries L, Van Der Ende A, Van Arkel G. A host–vector system for gene cloning in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:185–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00330208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducat DC, Way JC, Silver P. Engineering cyanobacteria to generate high-value products. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai J, Vepritskiy A, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E, Wolk P. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1998-2005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SS, Brusslan J, Haselkorn R. Genetic engineering of the cyanobacterial chromosome. Meth Enzymol. 1987;153:215–231. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerry P, van Embden J, Falkow S. Molecular nature of two non-conjugative plasmids carrying drug resistance genes. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:619–630. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.619-630.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidorn T, Camsund D, Huang HH, Lindberg P, Oliveira P, Stensjö K, Lindblad P. Synthetic biology in cyanobacteria engineering and analyzing novel functions. Meth Enzymol. 2011;497:539–579. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385075-1.00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie Y, Ito Y, Ono M, Moriwaki N, Kato H, Hamakubo Y, Amano T, Wachi M, Shirai M, Asayama M. Dark-induced mRNA instability involves RNase E/G-type endoribonuclease cleavage at the AU-box and SD sequences in cyanobacteria. Mol Genet Genomics. 2007;278:331–346. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-H, Camsund D, Lindblad P, Heidorn T. Design and characterization of molecular tools for a synthetic biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2577–2593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura S, Asayama M. Sigma factors for cyanobacterial transcription. Gene Regul System Bio. 2009;3:65–87. doi: 10.4137/grsb.s2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura S, Yoshihara S, Nakano S, Shiozaki N, Yamada A, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Asayama M, Shirai M. Purification, characterization, and gene expression of all sigma factors of RNA polymerase in a cyanobacterium. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:857–872. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Asayama M, Shirai M. Light-responsive psbA transcription requires the −35 hexamer in the promoter and its proximal upstream element, UPE, in cyanobacteria. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:1382–1390. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps S, Ferino F, Mosrin C, Gerits J, Mergeay M, Thuriaux P. Conjugative transfer and autonomous replication of a promiscuous IncP plasmid in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:129–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00280378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlemeier CJ, van Arkel GA. Host–vector systems for gene cloning in cyanobacteria. Meth Enzymol. 1987;153:199–215. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarre J, Chauvat F, Thuriaux P. Insertional mutagenesis by random cloning of antibiotic resistance genes into the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3449–3457. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3449-3457.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Sheng J, Curtiss R., III Fatty acid production in genetically modified cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6899–6904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103014108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraccini P, Bulteau S, Cassier-Chauvat C, Mermet-Bouvier P, Chauvat F. A conjugative plasmid vector for promoter analysis in several cyanobacteria of the genera Synechococcus and Synechocystis. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:905–909. doi: 10.1007/BF00021546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. Replication and conjugative mobilization of broad host-range IncQ plasmids. Plasmid. 2009;62:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RJ, Shapiro JA. Genetic organization of the broad-host-range IncP-1 plasmid R751. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:1362–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.3.1362-1373.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R, Hinds M, Brasch M. Properties of R1162, a broad-host-range, high-copy-number plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:552–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.552-562.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulo P, Sicora C, Aro E-M. Cyanobacterial psbA gene family: optimization of oxygenic photosynthesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3697–3710. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WO, Zentella R, Wang Y, Taylor JS, Pakrasi HB. PhrA, the major photoreactivating factor in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 codes for a cyclobutane–pyrimidine–dimer-specific DNA photolyase. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:412–417. doi: 10.1007/s002030000164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa T, Hanami T, Hirano E, Miura T, Watanabe Y, Takanezawa A, Komatsuzaki M, Ohta H, Shirai M, Asayama M. Isolation and molecular characterization of a multicellular cyanobacterium, Limnothrix/Pseudanabaena sp. strain ABRG5-3. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74:1827–1835. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings DE, Tietze E. Comparative biology of IncQ and IncQ-like plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:481–496. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.4.481-496.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R. Isolation and purification of cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:3–27. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Shibato J, Aida T, Asayama M, Shirai M. Light-responsive and rhythmic gene expression of psbA2 Microcystis aeruginosa K-81. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1996;42:381–391. doi: 10.2323/jgam.42.381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Boussiba S, Vermaas WFJ. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strains lacking photosystem I and phycobilisome function. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1853–1863. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.12.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibato J, Agrawal GK, Kato H, Asayama M, Shirai M. The 5′-upstream cis-sequences of cyanobacterial psbA: analysis of their roles in basal, light-dependent and circadian rhythmic transcription. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002;267:684–694. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai M, Matsumaru K, Ohtake A, Takamura Y, Aida T, Nakano M. Development of a solid medium for growth and isolation of axenic Microcystis strains (cyanobacteria) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2569–2571. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2569-2571.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. High frequency mobilization of Gram-negative bacterial replicons by the in vitro constructed Tn5-Mob transposon. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;196:413–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00436188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi I, Hayano D, Asayama M, Masahiro F, Watahiki M, Shirai M. Restriction barrier composed of an extracellular nuclease and restriction endonuclease in the unicellular cyanobacterium Microcystis sp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:107–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima Y, Sugiura M, Hagiwara H. A novel expression vector for the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus PCC 6301. DNA Res. 1994;1:181–189. doi: 10.1093/dnares/1.4.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T. Genetic analysis of cyanobacteria. In: Bryant DA, editor. The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T, Wolk P. Conjugal transfer of plasmids to cyanobacteria. Meth Enzymol. 1987;153:232–243. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tous C, Vega-Palas MA, Vioque A. Conditional expression of RNase P in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 allows detection of precursor RNAs. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29059–29066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima M, Sasaki NV, Fujiwara M, Ehira S, Ohmori M, Sato N. Early candidacy for differentiation into heterocysts in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:23–31. doi: 10.1007/s00203-009-0525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk CP, Vonshak A, Kehoe P, Elhai J. Construction of shuttle vectors capable of conjugative transfer from Escherichia coli to nitrogen-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1561–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Alvey RM, Byrne PO, Graham JE, Shen G, Bryant DA. Expression of genes in cyanobacteria: adaptation of endogenous plasmids as platforms for high-level gene expression in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Method Mol Biol. 2011;684:273–293. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-925-3_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HS, Golden JW. Heterocyst pattern formation controlled by a diffusible peptide. Science. 1998;282:935–938. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinchenko VV, Piven IV, Melnik VA, Shestakov SV. Vectors for the complementation analysis of the cyanobacterial mutants. Russian J Genetics. 1999;35:228–232. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 52 kb)