The essence of the beautiful is unity in variety.

—Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn, the famous Romantic composer, sought to take the unique experiences of each human life—distinctive sorrows and personal pleasures—and give them universal expression in his music. Likewise, a key goal of science is to take diverse phenomena and ask whether such diversity can be unified at a deeper level. Darwin, for instance, saw a common process underlying the diversity of species, and Maxwell saw a common set of equations uniting both electricity and magnetism. In our target article (Gray, Young, & Waytz, this issue), we suggested that the diversity of moral judgment is underlain by the moral dyad, a psychological template of two perceived minds—a moral agent and a moral patient.

This idea is inspired by decades of research from cognitive psychology suggesting that concepts1 (e.g., birds, dogs, furniture) are understood not as strict definitions but as prototypes or exemplar sets (Murphy, 2004). In the case of morality, we suggest that this prototype is interpersonal harm: an intentional moral agent causing suffering to a moral patient. This dyad not only serves to represent the most canonical and powerful examples of immorality, but—more important—acts as a cognitive working model or template through which all morality is understood (Craik, 1967). In the target article, we summarized this statement as “mind perception is the essence of morality,” which helps explains not only the general correspondence between perceptions of mind and moral judgments (Bastian, Laham, Wilson, Haslam, & Koval, 2011; H. M. Gray, Gray, Wegner, 2007) but also diverse real-world phenomena (to answer questions of pragmatic validity; Graham & Iyer, this issue). Among these phenomena are dehumanization (Castano & Giner-Sorolla, 2006; Waytz & Epley, 2012), perceptions of torture (K. Gray & Wegner, 2010b), escaping blame (K. Gray & Wegner, 2011; Weiner, 1995), objectification (K. Gray, Knobe, Sheskin, Bloom, & Barrett, 2011; Heflick, Goldenberg, Cooper, & Puvia, 2011; Loughnan et al., 2010), the harming of saints (K. Gray & Wegner, 2009), the belief in God (Bering, 2002; K. Gray & Wegner, 2010a), the link between psychopathology and morality (K. Gray, Jenkins, Heberlein, & Wegner, 2011; Young, Koenigs, Kruepke, & Newman, 2012), the deliciousness of home cooking (K. Gray, 2012), and how good and evil deeds make people physically stronger (K. Gray, 2010).

Statements about the essence of anything, however, are likely to be controversial, and the 16 commentaries we received are proof of this. These 16 articles provide a wealth of insightful ideas, novel perspectives, and even some original data concerning dyadic morality and the link between mind perception and moral judgment. In this reply, we respond to questions raised in the commentaries primarily through clarification and refinement of our original thesis, but also through the reporting of new data and calls for future research. Specifically, we clarify the meaning of essence and harm, emphasize the nature of levels inherent in psychological phenomena, describe how our theory interfaces with other views of morality, and outline important future directions. Before beginning, we would first like to make a less controversial statement—constructive criticism is the essence of scientific advancement, and we are grateful to all those who took the time to write commentaries.

The Essential Confusion

In perhaps the ultimate irony of the English language, it is difficult to capture the essence of the word essence. This ambiguity means that much controversy about dyadic morality focused on the precise meaning of this word. What does it mean for mind perception to be the essence of morality? We provide three dictionary definitions of essence that combine to give a clearer picture of dyadic morality.

-

1.

“the most significant element, quality or aspect of a thing” (Merriam-Webster, 2012)

-

2.

“an abstract perfect or complete form of a thing” (Collins Dictionary, 2012)

-

3.

“the ultimate nature of a thing” (Merriam-Webster, 2012)

The Most Significant Element, Quality, or Aspect of a Thing

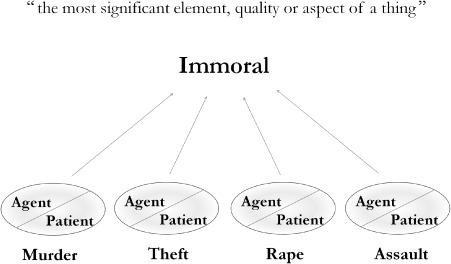

Morality is undoubtedly complex, with norms and injunctions varying across culture and time. Yet across all cultures, harm is immoral (Haidt, 2007). Potentially immoral acts include murder, theft, gambling, masturbation, prostitution, and blasphemy, but the most universally condemned acts involve both a moral agent and a moral patient—malicious intent and suffering (Figure 1). Indeed, when asked to list a single immoral act, participants from both America and India overwhelmingly offer a dyadic act (K. Gray & Ward, 2011); and when pitting immoral acts against each other, participants pick harmful acts as most important (van Leeuwen & Park, 2011). Thus, harm stands out as the most significant type of moral violation. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dyadic acts involving intention and suffering are those which are the most canonically and universally judged as immoral.

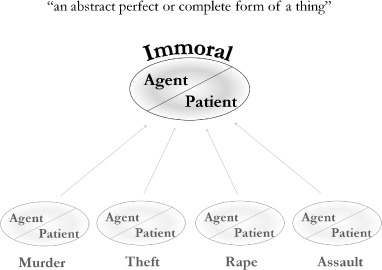

An Abstract Perfect or Complete Form of a Thing

The human mind understands concepts as prototypes, abstractions that distill unifying and canonical features from individual exemplars (Rosch, 1978). Given the frequency, universality, and affective power of harm, the prototype of immorality should reflect the canonical features of harm; and given that the central and common element across harmful acts is a dyadic structure, we suggest that the prototype of morality is also dyadic. More specifically, we suggest that overarching all specific moral acts is the fuzzy—but very real—dyadic cognitive template of an agent and patient, of intention causing suffering.2 See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Abstracted from specific judgments, a cognitive template of morality is formed, which represents immoral acts in general as a dyadic combination of agent and patient, intention and suffering.

In the target article, we suggested that this dyadic template is abstracted not only from the structure of moral events but also from the general structure of causality (Rochat, Striano, & Morgan, 2004) and language (Brown & Fish, 1983). New data presented by Strickland, Fisher, and Knobe (this issue) illustrates the broader link between causation, language, and judgments of mind and morality.3

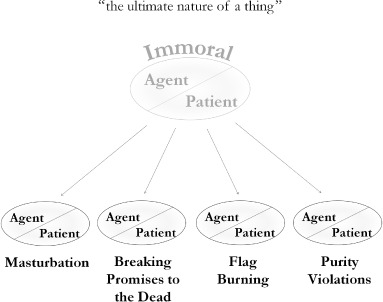

The Ultimate Nature of a Thing

Cognitive prototypes are not static representations but instead working models through which exemplars are ultimately understood (Craik, 1967; Murphy, 2004). We suggest that a dyadic template serves as a cognitive working model for morality and exerts a powerful top-down influence on moral cognition. This top-down influence leads people to understand all immoral acts as dyad and compels them to perceive an intentional agent and a suffering patient even when they may be objectively lacking.4 This idea is also advocated by Ditto, Liu, and Wojcik (i.e., explanatory coherence; this issue) and DeScioli, Gilbert, and Kurzban (this issue), who present original data in its support. It is important to note that the top-down influence exerted by a dyadic template is not post hoc rationalization, but provides a fundamental understanding of moral acts as dyadic (K. Gray & Ward, 2011) (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The dyadic template serves as a cognitive working model through which all moral events are viewed. This means that even “objectively” victimless misdeeds are perceived to have victims.

Thus, mind perception is the essence of morality not only because a dyad of two perceived minds represents morality's most important cases and its abstract prototype but also because all morality is ultimately understood through this dyadic template. As highlighted in the commentaries, the ties between mind perception and morality are both bottom-up and top-down: Perceived suffering and intention are both causes and consequences of moral judgment (Waytz, Gray, Epley, & Wegner, 2010). The important point is that when perception of mind changes, so too do judgments of morality, and when judgments of morality change, so too do perceptions of mind (Knobe, 2003).

Defining Harm

Just as commentators pointed out the ambiguity of essence, so too did they highlight the multifaceted nature of harm. Harm can be both a noun and a verb, but across definitions its most salient feature is suffering or damage, whether physical or otherwise. In the target article, we defined harm as perceived suffering seen to be caused intentionally by another agent. Thus, harm is not simply something that is “bad or immoral” but involves the perception of an intentional agent and a suffering patient. Separating judgments of wrongness from perceptions of harm is important because it avoids circularity (Rai & Fiske, this issue) and unfalsifiability (Graham & Iyer, this issue); it is both logically and empirically possible for an immoral act to be unlinked to perceptions of harm. Nevertheless, the evidence discussed in the target article suggests that people do tightly link judgments of immorality to perceived harm and intention.

Critical to our definition of harm is that it is perceived. It may be true that dead relatives (Sinnott-Armstrong, this issue) and nonhuman entities such as the natural environment (Monroe et al., this issue) or groups (Bauman, Wisneski, & Skitka, this issue) cannot be objectively harmed, but this does not preclude perceptions of harm. Research on anthropomorphism makes clear that people perceive mental states in a variety of human and nonhuman entities from alarm clocks, to dead relatives, groups, financial markets, and bacteria (Epley, Waytz, & Cacioppo, 2007; H. M. Gray et al., 2007). It is also clear that these perceptions have significant consequences for moral action and judgment toward such entities (H. M. Gray et al., 2007; Waytz, Epley, & Cacioppo, 2010). More broadly, the concept of objective harm is as fraught with difficulties as with objective morality; both morality and mind are in the eye of the perceiver, we simply suggest that these two perceptions are fundamentally bound together.

Levels of Analysis and Form Versus Content

A dyadic template provides a unified account of moral judgment, but many questioned the cost of this unification. Does a dyadic template cut away too much moral diversity, both within the domain of harm and beyond it? Fortunately, dyadic morality is fully consistent with a diverse, nuanced, and culturally variable description of moral judgment. The important point to recognize is that morality—like all psychological phenomena—can be described at a number of different levels, each of which captures unique variance (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1992).

The dyadic template is a social-cognitive account of morality—combining research on social perception and cognitive concepts—and focuses on what is both unique and unifying about moral judgment. At a higher level, cultural approaches describe variations of moral judgment across time and location (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Rai & Fiske, 2011; Shweder, Mahapatra, & Miller, 1987). At a lower level, neural and cognitive descriptions of morality demonstrate how moral judgment depends on domain-general networks and concepts, such as affect and cognition (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Haidt, 2001), causation (Cushman, 2008; Guglielmo, Monroe, & Malle, 2009), and action parsing (Mikhail, 2007). Although each of these levels is not reducible to the others, they are mutually consistent. Perhaps the best way to understand the compatibility of a dyadic template with other levels is to use the wonderful analogy provide by Bauman et al. (this issue): Dyadic harm is the common currency of morality.

Neural evidence supports the idea of “harm as moral currency.” The brain regions that respond to money lost or gained are similarly responsive to lives lost or saved, and sensitive to the probability of potential harm in moral scenarios (Shenhav & Greene, 2010). One apparent counterexample to this metaphor is that people are sometimes unwilling to harm one person to save five in trolley studies (Ditto et al., this issue). Failures to respect objective harm can be explained by again emphasizing the importance of perceived harm, whereby features that make harm perceptually salient should decrease the moral acceptability of actions. Indeed, manipulating harm's salience either directly—through visual availability (Greene & Amit, in press)—or indirectly—through elements such as personal force, acts versus omissions, means versus side effects (Cushman, Young, & Hauser, 2006), and the identifiability of victims (Small & Loewenstein, 2003)—will correspondingly influence the severity of moral judgments.

The metaphor of harm as moral currency also suggests that there is not an unbridgeable gap between moral judgments across relationships (Rai & Fiske, this issue) or cultures (Koleva & Haidt, this issue). Just as Pesos can be converted to Euros, so too can moral violations across cultures be compared on perceptions of harm. Thus, liberals and conservatives may not fundamentally misunderstand each other's moral judgments but instead simply disagree on what is harmful. Consistent with this claim, conservatives and liberals are equally committed to morality and use similar logic and rhetoric, despite apparent differences in the content of these moral intuitions (Skitka & Bauman, 2008).

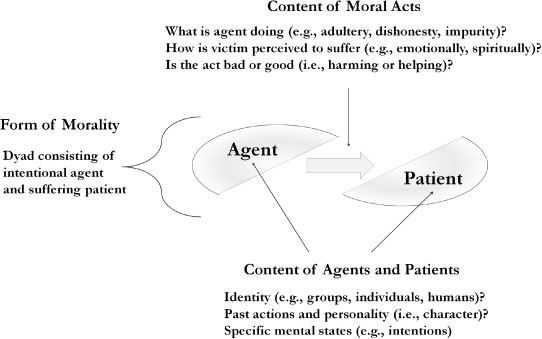

Although we suggest that mind perception is the essence of morality, we would not suggest that that is all of morality. We reconcile the diversity of morality—whether in terms of cultural variability or mental processes involved—with the moral dyad by using the distinction between form and content. The dyad suggests an essential form of agent and patient, intention and suffering, but the specific content of that form can change substantially.

Consider sports. The essential form of sports is organized competition between two (or more) parties, in which one party is the winner and the other(s) are losers. Despite this consistent form, the specific content of competition varies widely (e.g., wrestling, tennis), as do the specific characteristics of the competing parties (e.g., individual 100-lb gymnasts, groups of 300-lb linebackers).5 Now consider morality. The dyadic form persists across variable action content (e.g., disloyalty, unfairness) and variable agent and patient content (e.g., humanness, presence or lack of foresight) (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The dyad is a cognitive template of moral events, but this template is filled with two different kinds of content.

Specific Content of the Moral Acts

Moral judgments clearly concern more than just direct physical harm, but diverse moral concerns can remain unified by the dyad. An agent can be perceived to harm a patient through a number of specific actions, including physical violence, dishonesty, emotional abuse, and sexual impropriety. Thus, other compelling accounts of moral judgment—triune ethics (Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, & Park, 1997), moral foundations theory (Graham et al., 2009), and relational models theory (Rai & Fiske, 2011)—are all compatible with an underlying dyadic template, because they detail the specific content of moral acts rather than their underlying psychological form. This compatibility is made even more apparent by considering that these accounts are more anthropological than psychological, in that they divide moral content descriptively based upon evolutionary theorizing (Haidt & Joseph, 2004), case studies (Rai & Fiske, 2011), or factor analyses (Graham et al., 2011), rather than examining psychological mechanism. To be sure, such descriptive accounts are extraordinarily generative and explain such important real-world phenomena as political conflict (Ditto & Koleva, 2011), but one must be clear about their level of explanation.

In moral foundations theory, for instance, there is no clear explanation of what psychologically qualifies something as a foundation, nor is there evidence that the mind or the brain is structured into four (Haidt & Joseph, 2004), five (Haidt & Graham, 2007), or now six (Haidt, 2012) discrete moral modules. Indeed, both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses find that moral judgments across cultures are best accounted for by only two factors—individual- and group-oriented concerns—both of which focus upon entities perceived to have minds (Graham et al., 2011). There can be no doubt that the distinctness of each domain is intuitively compelling, but the psychological truth is not to be determined by intuition but instead by experiments that test the cognitive underpinnings of morality. Indeed, one study by K. Gray and Ward (2011) found that the descriptively different foundations are all cognitively linked to harm, just as a dyad template predicts. These data further suggest that out of five descriptive domains, only one—harm—is truly foundational.

As much research demonstrates and many commentators emphasized (e.g., Koleva & Haidt, this issue), morality varies across cultures, and it is important to test dyadic morality with non-WEIRD samples (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Compelling evidence for the cross-cultural power of dyadic morality was collected by Haidt and colleagues (Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993), who contrasted the moral judgments of rich, White, liberal Americans with those of poor, Black, conservative Brazilians. They found that although rich Americans did not often see ostensibly harmless transgressions (e.g., cleaning a toilet with the country's flag) as immoral, many more Brazilians did. Of importance, despite living in a culture that downplays the importance of harm, Brazilians nonetheless saw harm behind these moral transgressions, just as dyadic morality predicts.

A more specific test of the power of dyadic morality to explain moral intuitions was done by K. Gray and Ward (2011), who asked both conservative Americans and Indian participants whether transgressions from each of the five “foundations” was immoral and whether it harmed a victim. As predicted, judgments of immorality were linked to the perception of victimhood, even for ostensibly victimless acts, and even without the need to justify responses. These data not only provide support for dyadic morality but also cast doubt on the host of studies that make claims about morality based on scenarios of victimless transgressions (e.g., Graham et al., 2009; Haidt, 2001). Harm is a matter of perception, and so the inability of researchers to see victims in their own scenarios does not mean that such victims are not apparent to their conservative participants.

A promising candidate for synthesizing a dyadic template with descriptively different domains is advanced by Janoff-Bulman and colleagues (Carnes & Janoff-Bulman, this issue; Janoff-Bulman, 2009; Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh, & Hepp, 2009), who combine harm and help with the opposing motivational orientations of approach and avoidance. This model accounts for such political disagreement between liberals (who focus on the promotion of good) and conservatives (who focus on the prevention of harm; Janoff-Bulman, 2009) and also highlights the importance of good deeds, which has so far been mostly missing from our account of dyadic morality (Sinnott-Armstrong, this issue). Of interest, judgments of good deeds appear to concern the alleviation of suffering rather than the causation of pleasure, highlighting the importance of perceived harm and further suggesting that people fail to see good outcomes as moral unless they are preceded by victimization (Carnes & Janoff-Bulman, this issue). This framework also suggests that moral judgment can vary depending on whether agents and/or patients are individuals or groups. Indeed, the specific content of the characteristics of agents and patients can lead to differences in moral judgment.

Specific Content of Moral Agents and Moral Patients

Just as the specific action linking agent to patient can vary, so too can the specific characteristics of agents and patients. As we suggest, the defining feature of agents and patients is mind—perceptions of agency and experience—but other factors are no doubt important. In terms of general characteristics, whether agents and patients are individuals or groups—or individuals within groups (Waytz & Young, 2012)—can influence moral judgments. Such moral judgments are accompanied by corresponding differences in mind perception, however (H. M. Gray et al., 2007; Knobe, 2003). Haslam (this issue) suggests that humanness also adds unique moral status, and although much of humanness is tied to agency and experience, some elements may not be, such as openness and individual depth.6 Another important general characteristic of others is whether they come from the in-group or out-group: Out-group agents are afforded more blame, and out-group patients are afforded less concern, two phenomena also mirrored by corresponding differences in mind perception (Pettigrew, 1979; Goff, Eberhardt, Williams, & Jackson, 2008).

More specific than the general content of who (or what) occupies the slots of agent and patient are people's personalities and past actions. Stable impressions of an agent's character influence blame and punishment (Alicke, this issue; Alicke, 2000; Pizarro & Tannenbaum, 2011; Pizarro, Tannenbaum, & Uhlmann, this issue), and a patient's perceived character influences sympathy and punishment (K. Gray & Wegner, 2009; Weiner, 1980). Research suggests, however, that when people perceive others, inferences of mind are more primary than judgments of personality (Malle & Holbrook, 2012; Smith & Miller, 1983), which points to the primacy of mind perception. Indeed, even factors such as the belief in free will (Baumeister & Vonasch, this issue) can be seen to exert their effects through perceptions of mind—the mental capacity of the agent to have done otherwise.

Even more specifically than identity and character, particular mental capacities and contents ascribed to agents and patients can influence moral judgment. Research reveals that moral agents are blamed more for misdeeds when they are intended, foreseen and skillfully executed in the manner planned (Cushman, 2008; Dillon & Cushman, this issue; Malle, Guglielmo, & Monroe, in press; Monroe et al., this issue; Pizarro, Uhlmann, & Bloom, 2003). One question raised by dyadic morality is whether complementary factors apply to moral patients.

Future Directions

The target article attempted to not only integrate work on mind perception and morality but also generate novel questions for future research. Along these lines, commentators suggested a number of important research avenues, and here we focus on four.

The Dyad Within Us

One concern raised by commentators is how dyadic morality can account for immoral acts performed by the self and on the self (e.g., masturbation, alcoholism; Alicke, this issue; Sinnott-Armstrong, this issue). As discussed in the target article, observers who condemn these acts often do appeal to other victims—both concrete and abstract, individuals and groups (e.g., God, the agent's relatives, social institutions, future generations). Nevertheless, we recognize that in many instances it does appear to be the self that is perceived as the key victim—in other words, the self is both the agent and the patient. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that purity violations represent harms directed toward the self (DeScioli et al., this issue; Dungan, Chakroff, & Young, 2012; Young & Saxe, in press). For example, consensual incest and ingestion of taboo substances are often condemned even when they directly affect (i.e., harm) only the parties who participate in the act.

How can dyadic morality accommodate cases in which the agents are also the patients? Important work in temporal discounting and self-control suggests that the self is itself dyadic (Bartels & Urminsky, 2011; Ersner-Hershfield, Wimmer, & Knutson, 2009; Mitchell, Schirmer, Ames, & Gilbert, 2010). When people deliberate over what to do and how to behave, they often consider how their present actions (i.e., the present self) will affect their future self. Similarly, when people evaluate the here and now, they might regret or condemn past actions (i.e., their past self) that resulted in negative consequences for the present self. For example, when considering whether to take heroin, an agent may weigh the immediate high against lasting harm and addiction for his or her future self. Consistent with this notion of the dyadic self, research finds that people are less likely to make myopic decisions (associated with negative impact for the future self) when the future self is made salient (Hershfield et al., 2011) or when they feel psychologically connected to this future self (Bartels & Urminsky, 2011; Ersner-Hershfield et al., 2009). Additional research suggests that priming people to think of their future selves as “close others” (e.g., akin to one's relatives) leads them to avoid harming their future selves by making poor decisions in the moment (i.e., the present self can harm the future self; Bryan & Hershfield, 2011). These studies suggest a clear hypothesis for future research: The more observers judge a self-oriented action (e.g., masturbation) as immoral, the more they should judge the action as directly harming the person's future self.

Beyond the Dyad

Both others and oneself may perceived as moral patients, but a number of commentators suggested that some moral judgments may still be best cast in nonutilitarian terms (e.g., some acts are wrong independent of any consideration of harmful outcomes to anyone). We suggest that norms concerning “harmless” violations may still function as broad heuristics that evolved to guard against harm to individuals, groups, or sociocultural institutions (Alicke, this issue; Pizarro et al., this issue). Thus, although individual violations may not involve objective harm, undermining the norm itself can lead to harm more broadly. For example, the infamous incest case of Mark and Julie may cause no immediate harm (Haidt, 2001), but approving of incest in this case weakens the prohibition against more harmful—and typical—instances of familial love-making. This suggests that the perception of individual suffering caused by ostensibly harmless misdeeds should be mediated by the perception of weakened norms and social institutions. Indeed, those who rally against ostensibly harmless violations such as homosexuality suggest that they represent the beginning of a slippery slope in which all norms and standards are abandoned, thereby plunging people into deadly anarchy (Bryant, 1977).

Although the concept of the moral patient can encompass the self or society, commentators suggested that self and society could also take on the role of moral judge, resulting in triadic morality: agent, patient, and judge (Baumeister & Vonasch, this issue; DeScioli et al., this issue). The importance of judges is clear both descriptively and empirically. In largescale human societies, third-party judges—rather than victims or perpetrators themselves—are responsible for moral judgments and enforcement (DeScioli & Kurzban, 2009), and research demonstrates that making judges psychologically salient increases pro-social behavior (Haley & Fessler, 2005; Shariff & Norenzayan, 2007). But although morality may be amenable to a triadic description, is it psychologically encoded as such?

We suggest that people may rely on dyadic terms for conceptualizing triadic acts. For example, when subjects splitting money in a dictator game are primed to think of God (Shariff & Norenzayan, 2007), they may conceive of three dyads: self harming other, God harming self; and God compensating other. In this dyadic account, God is simply a superordinate agent who can influence the original agent and patient in a moral interaction. Indeed, people typically perceive God to have the mental qualities of a moral agent (K. Gray & Wegner, 2010a), and other judges may be seen similarly. One way to pit triadic and dyadic accounts against each other is to test whether triadic encounters (agent harms patient; judge punishes agent; judge compensates patient) are encoded as a single moral act (triadic prediction) or as three separate moral acts (dyadic prediction).

Psychopathology and Neuroscience

An important goal for future research is to clarify the link between mind perception, psychopathology, and neuroscience (Haslam, this issue; Sinnott-Armstrong, this issue). In the target article, we suggested that psychopathy is underscored by deficits in experience perception (e.g., patiency), and autism is underscored by deficits in agency perception. A key prediction of this claim is that psychopathy and autism should both be characterized by distinct and abnormal moral judgments.

Without an appreciation of the suffering of others, psychopaths should judge harmful actions to be more morally permissible. Recent evidence shows that psychopaths do judge harmful accidents as relatively more permissible, in part because they lack an empathic response to victims’ pain (Young et al., 2012). One question is why psychopaths do not deliver more lenient judgments of intentional harms (Cima, Tonnaer, & Hauser, 2010; Glenn, Raine, & Schug, 2009)? A likely answer is that an intact understanding of agency allows them to translate the malicious intent of the agent into judgments of wrongdoing (Dolan & Fullam, 2004). The importance of experience perception is also made salient in the abnormal moral judgments of psychopaths (Bartels & Pizarro, in press) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex patients (Koenigs et al., 2007) who fail to consider the emotional experiences of victims and thus deliver moral judgments according to cold calculations.

Turning to autism, a question raised by commentators is why those on the spectrum judge accidents more harshly? First, as suggested by Dillon and Cushman (this issue), deficits in general agency perception may be overshadowed by larger deficits in understanding specific intention and goals. Second, accidents require a particularly robust understanding of the agent's mind in order to overcome the prepotent empathic response to the victim's negative experience, which remains intact in autism (Rogers, Dziobek, Hassenstab, Wolf, & Convit, 2006).

Future work should investigate the neural substrates that support processing of agency and patiency. As recent work has shown, brain regions associated with pain processing and experience (right anterior insula, anterior midcingulate cortex, periaqueductal gray) are robustly recruited in response to those who are typecast as moral patients (Decety, Echols, & Correll, 2009). Research should also explore the neural currency underlying trade-offs in ascriptions of pain and those of responsibility (Gray & Wegner, 2009).

Development

Key questions remain about the emergence of the moral dyad. As Hamlin (this issue) noted, most developmental research is consistent with dyadic morality, but there is debate about the importance of suffering in the moral judgment of young children, because they offer help without outward signs of distress (Hamlin, Ullman, Tenenbaum, Goodman, & Baker, 2012; Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2009). Even without external displays of suffering, however, children are still able to infer the presence of suffering through affective perspective taking (Vaish et al., 2009).

In addition to testing general links between perceptions of agency and experience and moral judgment, future research should also test whether the corollaries of dyadic morality—dyadic completion and moral typecasting—also emerge early in development. There is some evidence that young children will infer the presence of an agent to account for suffering (Hamlin & Baron, 2012), but it is unknown whether the presence of evil leads to the inference of suffering. Likewise, do children assign outcomes based on the predictions of moral typecasting (Gray & Wegner, 2009), harming both sinners and saints, and forgiving victims?

Conclusion

In this reply, we have clarified the meaning of the claim “mind perception is the essence of morality” and have highlighted the key elements of the theory of dyadic morality—the importance of perceived harm, the distinction of form versus content, and the multilevel nature of psychological phenomenon. We have also outlined a number of important remaining questions to be addressed by future research.

Newton said, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” and in this issue, we have been lucky to be lifted up by many giants. The theory of dyadic morality—and the general link between mind perception and moral judgment—has benefited greatly from the feedback of many eminent moral psychologists. We hope that the theory is now clearer, is stronger, and provides a better basis for future investigation. Morality may need two minds, but scientific advancement takes many, many more.

Notes

Of sufficient complexity. Even numbers, for example, are not sufficiently complex (Sinnott-Armstrong, this issue).

The importance of causation is highlighted by Dillon and Cushman (this issue) and Monroe, Guglielmo, and Malle (this issue). It must emphasized, however, that causation—like mind—is often more about perceptions than reality (Hume, 1740; Pronin, Wegner, McCarthy, & Rodriguez, 2006).

In particular, their data suggest that that the dyadic structure of general action can influence moral judgment. They further suggest that these influences can fully account for dyadic morality, but previous data highlight the uniqueness of the moral domain (e.g., Studies 4a and 4b, Gray & Wegner, 2009).

The analogy used in the target article is the Kanisza triangle, where top-down influences in vision compel people to see two triangles.

Strickland et al. (this issue) also use a sports analogy.

In a study designed to test the overlap of dimensions of mind perception (H. M. Gray et al., 2007) and those of humanness (Haslam, 2006), we obtained ratings (N = 76) toward 13 targets (including humans, animals, inanimate objects, God, and Google) of perceived hunger, pain, and fear (experience); self-control, planning, and memory (agency); openness and individual depth (human nature); and civility and rationality (uniquely human). Correlational analyses revealed that judgments of uniquely human traits were highly correlated with agency, r(11) = .92, p < .001, suggesting that these are widely overlapping constructs. On the other hand, the correlation between experience and human nature traits was lower, r(11) = .45, p = .12, suggesting some overlap but also some important distinction between these concepts. This lower correlation stems from the fact that animals are rated as high on experience, but lower on human nature traits.

References

- Alicke M. D. Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:556–574. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D. M., Pizarro D. A. The mismeasurement of morals: Antisocial personality traits predict utilitarian responses to moral dilemmas. Cognition. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bartels D. M., Urminsky O. On intertemporal selfishness: How the perceived instability of identity underlies impatient consumption. Journal of Consumer Research. 2011;38:182–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian B., Laham S. M., Wilson S., Haslam N., Koval P. Blaming, praising, and protecting our humanity: The implications of everyday dehumanization for judgments of moral status. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;50:469–483. doi: 10.1348/014466610X521383. doi:10.1348/014466610×521383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bering J. M. The existential theory of mind. Review of General Psychology. 2002;6(1):3–24. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.1.3. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R., Fish D. The psychological causality implicit in language. Cognition. 1983;14:237–273. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90006-9. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(83)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C. J., Hershfield H. E. You owe it to yourself: Boosting retirement saving with a responsibility-based appeal. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (Advance online Publication) 2011. doi:10.1037/a0026173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bryant A. The Anita Bryant story: The survival of our nation's families and the threat of militant homosexuality. Grand Rapids, MI: Revell; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Berntson G. G. Social psychological contributions to the decade of the brain: Doctrine of multilevel analysis. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1019–1028. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.8.1019. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano E., Giner-Sorolla R. Not quite human: Infrahumanization in response to collective responsibility for intergroup killing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:804–818. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.804. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima M., Tonnaer F., Hauser M. D. Psychopaths know right from wrong but don't care. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:59–67. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp051. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Dictionary. Essence. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/essence.

- Craik K. J. W. The nature of explanation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F. Crime and punishment: Distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analyses in moral judgment. Cognition. 2008;108:353–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F., Young L., Hauser M. The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgment: Testing three principles of harm. Psychological Science. 2006;17:1082–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01834.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Echols S., Correll J. The blame game: The effect of responsibility and social stigma on empathy for pain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;22:985–997. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21266. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeScioli P., Kurzban R. Mysteries of morality. Cognition. 2009;112:281–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditto P. H., Koleva S. P. Moral empathy gaps and the American culture war. Emotion Review. 2011;3:331–332. doi:10.1177/1754073911402393. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan M., Fullam R. Theory of mind and mentalizing ability in antisocial personality disorders with and without psychopathy. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1093–1102. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungan J., Chakroff A., Young L. Purity versus pain: Distinct moral concerns for self versus others. 2012. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Eberhardt J. L., Davies P. G., Purdie-Vaughns V. J., Johnson S. L. Looking deathworthy perceived stereotypicality of black defendants predicts capitalsentencing outcomes. Psychological Science. 2006;17:383–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epley N., Waytz A., Cacioppo J. T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review. 2007;114:864–886. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersner-Hershfield H., Wimmer G. E., Knutson B. Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4:85–92. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn042. doi:10.1093/scan/nsn042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn A. L., Raine A., Schug R. A. The neural correlates of moral decision-making in psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:5–6. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.104. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff P. A., Eberhardt J. L., Williams M. J., Jackson M. C. Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:292–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J., Haidt J., Nosek B. A. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141. doi:10.1037/a0015141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J., Nosek B. A., Haidt J., Iyer R., Koleva S., Ditto P. H. Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:366–385. doi: 10.1037/a0021847. doi:10.1037/a0021847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. M., Gray K., Wegner D. M. Dimensions of mind perception. Science. 2007;315:619. doi: 10.1126/science.1134475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K. Moral transformation: Good and evil turn the weak into the mighty. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2010;1:253–258. doi:10.1177/1948550610367686. [Google Scholar]

- Gray K. The power of good intentions: Perceived benevolence soothes pain, increases pleasure, and improves taste. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012. (Advance online publication.), doi:10.1177/1948550611433470.

- Gray K., Jenkins A. C., Heberlein A. S., Wegner D. M. Distortions of mind perception in psychopathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:477–479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015493108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Knobe J., Sheskin M., Bloom P., Barrett L. F. More than a body: Mind perception and objectification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1207–1220. doi: 10.1037/a0025883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Ward A. F. The harm hypothesis: Perceived harm unifies morality. 2011. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Gray K., Wegner D. M. Moral typecasting: Divergent perceptions of moral agents and moral patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:505–520. doi: 10.1037/a0013748. doi:10.1037/a0013748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Wegner D. M. Blaming God for our pain: Human suffering and the divine mind. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010a;14:7–16. doi: 10.1177/1088868309350299. doi:10.1177/1088868309350299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Wegner D. M. Torture and judgments of guilt. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010b;46:233–235. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.10.003. [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Wegner D. M. To escape blame, don't be a hero—Be a victim. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;47:516–519. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.12.012. [Google Scholar]

- Greene J. D., Amit E. You see, the ends don't justify the means: Visual imagery and moral judgment. Psychological Science. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Greene J. D., Sommerville R. B., Nystrom L. E., Darley J. M., Cohen J. D. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science. 2001;293:2105–2108. doi: 10.1126/science.1062872. doi:10.1126/science.1062872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo S., Monroe A. E., Malle B. F. At the heart of morality lies folk psychology. Inquiry. 2009;52:449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science. 2007;316:998–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1137651. doi:10.1126/science.1137651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York, NY: Pantheon; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J., Graham J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research. 2007;20(1):98–116. doi:10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J., Joseph C. Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus. 2004;133(4):55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J., Koller S. H., Dias M. G. Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:613–628. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley K. J., Fessler D. M. T. Nobody's watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2005;26:245–256. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.01.002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin J. K., Baron A. S. My computer's out to get me: 6-month-old infants attribute agency to the mechanical causes of negative outcomes. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia; 2012. Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin J. K., Ullman T., Tenenbaum J. B., Goodman N., Baker C. The mentalistic basis of core social cognition: Experiments in preverbal infants and a computational model. 2012. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haslam N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflick N. A., Goldenberg J. L., Cooper D. P., Puvia E. From women to objects: Appearance focus, target gender, and perceptions of warmth, morality and competence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;47:572–581. doi:16/j.jesp.2010.12.020. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J., Heine S., Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2010;33(2–3):61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield H. E., Goldstein D. G., Sharpe W. F., Fox J., Yeykelis L., Carstensen L. L., Bailenson J. N. Increasing saving behavior through age-progressed renderings of the future self. Journal of Marketing Research. 2011;48:S23–S37. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S23. doi:10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume D. A treatise of human nature. New York, NY: Dover; 1740. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. To provide or protect: Motivational bases of political liberalism and conservatism. Psychological Inquiry. 2009;20:120. doi:10.1080/10478400903028581. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R., Sheikh S., Hepp S. Prescriptive versus prescriptive morality: Two faces of moral regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:521–537. doi: 10.1037/a0013779. doi:10.1037/a0013779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobe J. Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis. 2003;63:190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M., Young L., Adolphs R., Tranel D., Cushman F., Hauser M., Damasio A. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature. 2007;446:908–911. doi: 10.1038/nature05631. doi:10.1038/nature05631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughnan S., Haslam N., Murnane T., Vaes J., Reynolds C., Suitner C. Objectification leads to depersonalization: The denial of mind and moral concern to objectified others. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40:709–717. doi:10.1002/ejsp.755. [Google Scholar]

- Malle B. F., Guglielmo S., Monroe A. E. Moral, cognitive, and social: The nature of blame. In: Forgas J., Fiedler K., Sedikides C., editors. Social thinking and interpersonal behavior. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Malle B. F., Holbrook J. Is there a hierarchy of social inferences? The likelihood and speed of inferring intentionality, mind, and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:661–684. doi: 10.1037/a0026790. doi:10.1037/a0026790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Essence. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/essence.

- Mikhail J. Universal moral grammar: Theory, evidence and the future. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.007. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. P., Schirmer J., Ames D. L., Gilbert D. T. Medial prefrontal cortex predicts intertemporal choice. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;23:857–866. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21479. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G. L. The big book of concepts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew T. F. The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport's cognitive analysis of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1979;5(4):461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro D. A., Tannenbaum D. Bringing character back: How the motivation to evaluate character influences judgments of moral blame. In: Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R., editors. The social psychology of morality: Exploring the causes of good and evil. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2011. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro D. A., Uhlmann E., Bloom P. Causal deviance and the attribution of moral responsibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:653–660. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00041-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E., Wegner D. M., McCarthy K., Rodriguez S. Everyday magical powers: The role of apparent mental causation in the overestimation of personal influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:218–231. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.218. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai T. S., Fiske A. P. Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychological Review. 2011;118(1):57–75. doi: 10.1037/a0021867. doi:10.1037/a0021867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat P., Striano T., Morgan R. Who is doing what to whom? Young infants’ developing sense of social causality in animated displays. Perception. 2004;33:355–369. doi: 10.1068/p3389. doi:10.1068/p3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K., Dziobek I., Hassenstab J., Wolf O. T., Convit A. Who cares? Revisiting empathy in asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;37:709–715. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0197-8. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E. Priniciples of categorization. In: Rosch E., Lloyd B. B., editors. Cognition and Categorization. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shariff A. F., Norenzayan A. God is watching you: Priming God concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous economic game. Psychological Science. 2007;18:803–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01983.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav A., Greene J. D. Moral judgments recruit domain-general valuation mechanisms to integrate representations of probability and magnitude. Neuron. 2010;67:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.020. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shweder R. A., Mahapatra M., Miller J. Culture and moral development. In: Kagan J., Lamb S., editors. The emergence of morality in young children. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder R. A., Much N. C., Mahapatra M., Park L. Morality and health. New York, NY: Routledge; 1997. The “big three” of morality (autonomy, community, and divinity), and the “big three” explanations of suffering; pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- Skitka L. J., Bauman C. W. Moral conviction and political engagement. Political Psychology. 2008;29:29–54. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00611.x. [Google Scholar]

- Small D. A., Loewenstein G. Helping a victim or helping the victim: Altruism and identifiability. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2003;26(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. R., Miller F. D. Mediation among attributional inferences and comprehension processes: Initial findings and a general method. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:492–505. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.3. 492. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A., Carpenter M., Tomasello M. Sympathy through affective perspective taking and its relation to prosocial behavior in toddlers. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:534–543. doi: 10.1037/a0014322. doi:10.1037/a0014322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen F., Park J. H. Moral virtues and political orientation: Assessing priorities under constraint. 2011. Unpublished manuscript, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

- Waytz A., Epley N. Social connection enables dehumanization. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012;48:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Waytz A., Epley N., Cacioppo J. T. Social cognition unbound. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:58–62. doi: 10.1177/0963721409359302. doi:10.1177/0963721409359302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waytz A., Gray K., Epley N., Wegner D. M. Causes and consequences of mind perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waytz A., Young L. The group-member mind tradeoff: Attributing mind to groups versus group members. Psychological Science. 2012;23:77–85. doi: 10.1177/0956797611423546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. A cognitive (attribution)-emotion-action model of motivated behavior: An analysis of judgments of help-giving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. Judgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of conduct of social conduct. New York, NY: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Young L., Koenigs M., Kruepke M., Newman J. P. Psychopathy increases perceived moral permissibility of accidents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0027489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Young L., Saxe R. The role of intent for distinct moral domains. Cognition. 2011;120:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]