Abstract

Objective To investigate whether exposure to spironolactone treatment affects the risk of incident breast cancer in women over 55 years of age.

Design Retrospective, matched cohort study.

Setting General Practice Research Database, a primary care anonymised database representative of the general population in the United Kingdom.

Participants 1 290 625 female patients, older than 55 years and with no history of breast cancer, from 557 general practices with a total follow-up time of 8.4 million patient years. We excluded patients with poor quality data and those with no contacts with their general practitioner after their current registration date.

Intervention Exposed cohort included women who received at least two prescriptions of spironolactone after age 55 years, who were followed up from the first prescription (index date). We randomly selected two unexposed female controls for every exposed patient, matched by practice, year of birth, and socioeconomic scores (if information was available), and followed up from the same date.

Main outcome measure New cases of breast cancer, using Read codes to confirm diagnoses.

Results Index dates for study patients ranged from 1987 to 2010, and 29 491 new cases of breast cancer were recorded in the study population (incidence rate 0.35% per year). The exposed cohort of 28 032 patients and control cohort of 55 961 patients had unadjusted incidence rates of 0.39% and 0.38% per year, respectively, over a mean follow-up time of 4.1 years. Time-to-event analysis, adjusting for potential risk factors, provided no evidence of an increased incidence of breast cancer in patients exposed to spironolactone (hazard ratio 0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.12).

Conclusions These data suggest that the long term management of cardiovascular conditions with spironolactone does not increase the risk of breast cancer in women older than 55 years with no history of the disease.

Introduction

The aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone, is widely used to treat chronic conditions including cardiovascular conditions and liver disease in patients in the United Kingdom. In particular, long term prescription of spironolactone for heart failure and hypertension has increased markedly over the past 10-12 years. For heart failure, this increase followed the publication of the Randomised Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES), which showed that spironolactone improved survival in patients with severe left ventricular failure.1 For hypertension, the recently updated2 and previous versions of guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and British Hypertension Society3 suggest spironolactone as an option in the treatment of resistant hypertension. However, despite its increasing use in this specialty, spironolactone is not currently licensed for the treatment of hypertension in the UK; the licence was withdrawn in 1988 after concerns of malignancy in animal models.4 The British National Formulary’s entry for spironolactone still carries a caution: “potential metabolic products carcinogenic in rodents.”5 The recent NICE guideline for hypertension suggests that doctors should seek informed consent from patients before prescribing spironolactone for hypertension, despite it now being the recommended first choice treatment for resistant hypertension.

The metabolism of spironolactone is complex and poorly understood in humans, but it is believed to have a number of potentially active metabolites, including canrenone and two sulphur containing metabolites, 7-α-thiomethylspirolactone and 6-β-hydroxy-7-α-thiomethylspirolactone.6 In addition to its actions on the mineralocorticoid receptor, spironolactone, directly or via its metabolites, also acts on other steroid receptors including via antiandrogenic and progestogenic routes. A common side effect of spironolactone is gynaecomastia, which is thought to be due to the drug’s effects on these receptors. The other available aldosterone antagonist, eplerenone, is more specific than spironolactone for the mineralocorticoid receptor and is likely to have fewer other hormonally based effects, but it is also less potent7 and much less commonly prescribed in the UK.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and about 80% of cases are hormonally dependent (usually oestrogen receptor positive). Because of the other effects of spironolactone on the breast (tenderness in women and gynaecomastia in men) and the known antiandrogenic and progestogenic actions, there has always been a concern that spironolactone could promote breast cancer development. Anecdotally, many doctors avoid prescribing spironolactone to patients with a history of breast cancer or at high risk of breast cancer since published reports expressed concern that the drug could increase the risk of breast cancers and other cancers in humans.8 9 10 However, other studies have shown no increased risk and overall, studies in this area have been small and limited.11 12 13 14 15

Many other factors are known to be associated with increased risk of breast cancer. These factors include age, sex (only 0.5% of cases occur in men), alcohol use, smoking, postmenopausal obesity, age at menarche, age at first child, age at menopause, parity, breastfeeding, use of exogenous oestrogens (such as hormone replacement therapy or combined oral contraceptive pill), family history, and in some cases, germline mutations (such as BRCA1). Patients who receive spironolactone treatment in the long term for hypertension or heart failure tend to be older, and this is also the group of patients most at risk of breast cancer. We aimed to investigate whether exposure to spironolactone affects the risk of incident breast cancer in women over 55 years of age in the UK.

Methods

Study design and hypothesis

We did a retrospective cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. This longitudinal database contains details of patients’ demographics, medical diagnoses, referrals to consultants and hospitals, and primary care prescriptions from a representative sample of general practices in the UK.16 The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the independent scientific advisory committee of the database before the study began. No further ethical approval is required for studies using the database that do not involve patient contact. We tested a prespecified hypothesis that exposure to spironolactone is associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer in women.

Study population

The study population included all women who contributed follow-up time to the database after the age of 55 years. The selected cut-off age is the age at which most women are postmenopausal and after which breast cancer becomes more common. Patients with unacceptable quality standard data, as determined by the General Practice Research Database, and patients with no contacts with their general practitioner after their current registration date were considered ineligible for this study. Eligible follow-up time for the remaining patients started from the latest date of their current registration date, their practice’s “up-to-standard” date, or 1 January of the year on which they reached the age of 55 years. Follow-up ended with patients’ last consultation date, unless this date was more than two years later than the penultimate consultation, in which case we used the contact date instead.

Study cohorts

We defined the exposed cohort as women who received at least two prescriptions of spironolactone after the age of 55 years. The date of the first of these prescriptions was defined as the index date. We constructed a control cohort by randomly selecting two female patients for every exposed patient who met the following criteria: registered with the same practice, and born in the same year (or within five years if no exact matches were found). In those practices that provided socioeconomic scores, matched patients also belonged to the same quintile of the distribution of scores. We assigned control patients the same index date as the exposed patient to whom they were matched. Patients who were subsequently exposed to spironolactone were eligible for inclusion in the control cohort before this exposure. When used as controls, these patients were censored at first exposure to spironolactone after the index date they had been assigned as a control.

We also constructed a control cohort matched on propensity scores for exposure to spironolactone, but we were unable to include all the covariates in the estimation of propensity scores due to non-convergence of the statistical procedures. However, although the propensity score matched analysis was incomplete, it did not show different results from the main analysis and is not reported here.

Outcomes

We used Read codes for confirmed diagnoses of breast cancer, including breast cancer in situ (table 1). The primary end point was the first incidence of breast cancer (invasive or in situ) after the index date. A secondary outcome excluded cases of breast cancer in situ.

Table 1.

Read codes for breast cancer used to define primary outcome

| Read code | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| B34..00 | Malignant neoplasm of female breast |

| B34..11 | Ca female breast |

| B340.00 | Malignant neoplasm of nipple and areola of female breast |

| B340000 | Malignant neoplasm of nipple of female breast |

| B340100 | Malignant neoplasm of areola of female breast |

| B340z00 | Malignant neoplasm of nipple or areola of female breast NOS |

| B341.00 | Malignant neoplasm of central part of female breast |

| B342.00 | Malignant neoplasm of upper-inner quadrant of female breast |

| B343.00 | Malignant neoplasm of lower-inner quadrant of female breast |

| B344.00 | Malignant neoplasm of upper-outer quadrant of female breast |

| B345.00 | Malignant neoplasm of lower-outer quadrant of female breast |

| B346.00 | Malignant neoplasm of axillary tail of female breast |

| B347.00 | Malignant neoplasm, overlapping lesion of breast |

| B34y.00 | Malignant neoplasm of other site of female breast |

| B34y000 | Malignant neoplasm of ectopic site of female breast |

| B34yz00 | Malignant neoplasm of other site of female breast NOS |

| B34z.00 | Malignant neoplasm of female breast NOS |

| B83..00 | Carcinoma in situ of breast and genitourinary system |

| B830.00 | Carcinoma in situ of breast |

| B830000 | Lobular carcinoma in situ of breast |

| B830100 | Intraductal carcinoma in situ of breast |

| BB9..00 | [M] Ductal, lobular, and medullary neoplasms |

| BB90.00 | [M] Intraductal carcinoma, non-infiltrating NOS |

| BB91.00 | [M] Infiltrating duct carcinoma |

| BB91.11 | [M] Duct carcinoma NOS |

| BB91000 | [M] Intraductal papillary adenocarcinoma with invasion |

| BB91100 | [M] Infiltrating duct and lobular carcinoma |

| BB92.00 | [M] Comedocarcinoma, non-infiltrating |

| BB93.00 | [M] Comedocarcinoma NOS |

| BB94.00 | [M] Juvenile breast carcinoma |

| BB94.11 | [M] Secretory breast carcinoma |

| BB9B.00 | [M] Medullary carcinoma NOS |

| BB9B.11 | [M] C cell carcinoma |

| BB9C.00 | [M] Medullary carcinoma with amyloid stroma |

| BB9E.00 | [M] Lobular carcinoma in situ |

| BB9E000 | [M] Intraductal carcinoma and lobular carcinoma in situ |

| BB9F.00 | [M] Lobular carcinoma NOS |

| BB9G.00 | [M] Infiltrating ductular carcinoma |

| BB9H.00 | [M] Inflammatory carcinoma |

| BB9J.00 | [M] Paget’s disease, mammary |

| BB9J.11 | [M] Paget’s disease, breast |

| BB9K.00 | [M] Paget’s disease and infiltrating breast duct carcinoma |

| BB9K000 | [M] Paget’s disease and intraductal carcinoma of breast |

| BB9L.00 | [M] Paget’s disease, extramammary, excluding Paget’s disease bone |

| BB9M.00 | [M] Intracystic carcinoma NOS |

| BB9z.00 | [M] Ductal, lobular, or medullary neoplasm NOS |

M= morphology of neoplasms; NOS=not otherwise specified.

Covariates

Covariates included age, calendar year of entry to study, Townsend score (socioeconomic status), use of combined oral contraceptive pill or hormone replacement therapy, history of benign breast disease, alcohol intake, body mass index, family history of breast cancer, use of drugs that may protect against breast cancer (aspirin, metformin), use of drugs causing gynaecomastia (digoxin, finasteride, cimetidine, nifedipine), and history of hypertension, heart failure, or diabetes mellitus. The number of British National Formulary drug classes prescribed was also included as a measure of general comorbidity. All covariates were evaluated on each patient’s index date. We also considered use of eplerenone as a covariate, but only eight patients in our study cohorts were prescribed it.

Statistical methods

We did time-to-event analyses using the intervals from the index date to the diagnosis of breast cancer (events) or the end of the follow-up period (censored observations). Preliminary analyses suggested that a proportional hazards model was appropriate, and we therefore presented results as hazard ratios for breast cancer associated with spironolactone exposure, adjusted for significant covariates. The significant covariates were identified by a forward selection process, with the threshold for entry into the model set at P<0.05. All covariates were entered into the analysis as continuous variables.

Four covariates were not available for some patients: socioeconomic score (51 022 (61%) patients in practices that did not provide scores), body mass index (unknown in 17 442 (21%) patients), alcohol consumption (unknown in 31 700 (38%) patients), and maximum dose of spironolactone (dosing instructions not coded for 2285 (8%) patients in the exposed cohort). In view of the large proportion of patients affected, we excluded covariates with missing values from the primary analysis. We then did separate analyses for the subsets of patients with and without known values of the socioeconomic score, body mass index, and alcohol consumption. We also tested for a dose response to spironolactone, on a dose doubling scale, within the exposed cohort.

We did a first sensitivity analysis by excluding breast cancer in situ from the outcomes. In a second sensitivity analysis, we replaced missing covariate data with imputed values, although one assumption required by these techniques was not met (that the covariates had a multivariate normal distribution), and another might not have been true (that data were missing at random). A third sensitivity analysis used propensity scores to match patients within practices. Potential control patients were assigned index dates at random from the distribution of index dates in exposed patients. We evaluated all covariates on these dates, and estimated the probability of exposure to spironolactone using as many of these covariates as possible. The socioeconomic score was necessarily excluded in practices that did not provide it. Statistical analyses were done using SAS version 9.1.

Results

Study population

The study population consisted of 1 290 625 patients from 557 practices, with a total follow-up time of 8.4 million patient years. We recorded 29 491 incident cases of breast cancer in this population. Table 2 shows the incidence rates by age.

Table 2.

Incidence of breast cancer in study population of women aged 55 years or more

| Age (years) at start of year at risk | No of follow-up years | Incident cases of breast cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Rate (% per year) | ||

| 55-59 | 1 885 536 | 6114 | 0.324 |

| 60-64 | 1 424 017 | 5238 | 0.368 |

| 65-69 | 1 279 314 | 4537 | 0.355 |

| 70-74 | 1 188 027 | 3746 | 0.315 |

| 75-79 | 1 049 682 | 3558 | 0.339 |

| 80-84 | 813 372 | 3022 | 0.372 |

| 85-89 | 504 648 | 2049 | 0.406 |

| 90-94 | 219 840 | 953 | 0.434 |

| ≥95 | 70 845 | 274 | 0.389 |

| Total | 8 435 281 | 29 491 | 0.350 |

We identified 29 381 patients who received at least two prescriptions for spironolactone after the age of 55 years. Of these, 1349 patients had a history of breast cancer before their index date (or an undated breast cancer record in nine cases) and were excluded from the study. The exposed cohort consisted of the remaining 28 032 patients, of whom 49.6% received at least 12 prescriptions for spironolactone, 43.4% received a maximum dose of 25 mg/day, and only 1.2% received more than 200 mg/day (table 3).

Table 3.

Spironolactone prescriptions and maximum dose

| No (%) of patients | |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 28 032 (100.0) |

| 12 or more prescriptions | 13 911 (49.6) |

| Maximum dose (mg/day) | |

| 25 | 12 179 (43.4) |

| 50 | 7384 (26.3) |

| 100 | 4822 (17.2) |

| 200 | 1022 (3.6) |

| >200 | 340 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 2285 (8.2) |

| First exposure before index date | 5078 (18.1) |

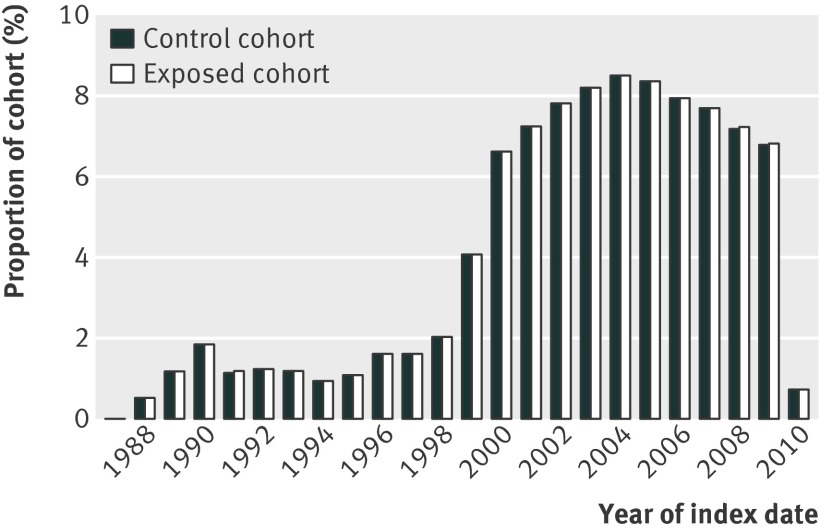

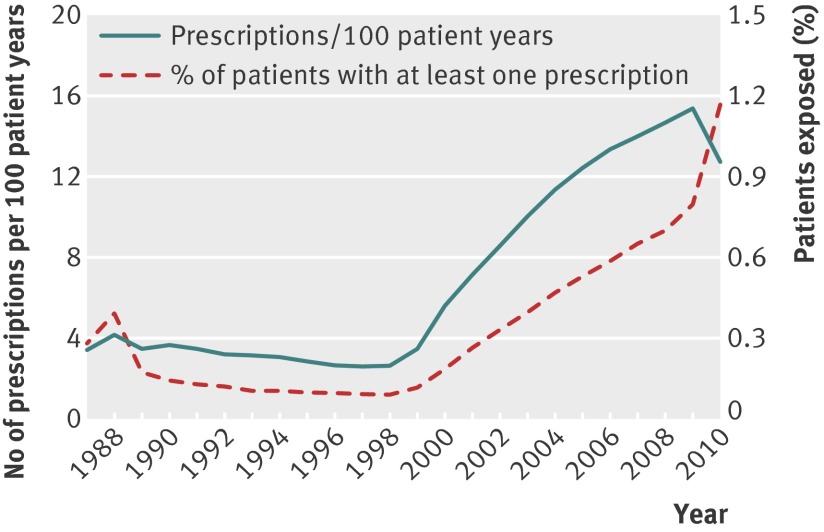

The index dates for patients in this study ranged from 1987 to 2010 (fig 1). The increase in patient numbers over time was partly the result of the recruitment of practices to the General Practice Research Database. However, there was also a rapid increase in the prescribing of spironolactone to women aged 55 years or more after 1999 (fig 2).

Fig 1 Distribution of index dates by year for 28 032 exposed patients and 55 961 control patients

Fig 2 Trends in spironolactone prescribing during study period

We identified 55 961 control patients (99.8% of the target number). They were matched to exposed patients on socioeconomic score in the 202 practices that provided them. Controls were also matched on exact year of birth in 53 647 (95.9%) cases. There was a maximum difference of five years in all other cases (2314 (4.1%)). Mean follow-up time in the study cohorts was 4.1 years.

Table 4 shows the distribution of all the covariates in the exposed and control cohorts. The use of oral contraceptives within the observation periods available in the database was low in both cohorts. The use of metformin, aspirin, steroids, and drugs that could affect the development of gynaecomastia was substantially higher in the spironolactone exposed cohort, and this group used a greater number of drug classes. There was a greater prevalence of diabetes and heart failure in the exposed cohort. The prevalence of other cancers was slightly greater in the exposed cohort, but a history of benign breast disease and a family history of breast cancer were slightly less common.

Table 4.

Distribution of covariates in the exposed and control cohorts. Data are no (%) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Cohort (no (%) of patients) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed (n=28 032) | Control (n=55 961) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| 55-59 | 2786 (9.9) | 5570 (10.0) | 1.000 |

| 60-64 | 2076 (7.4) | 4152 (7.4) | |

| 65-69 | 2699 (9.6) | 5395 (9.6) | |

| 70 to 74 | 3619 (12.9) | 7236 (12.9) | |

| 75 to 79 | 4748 (16.9) | 9487 (17.0) | |

| 80 to 84 | 5097 (18.2) | 10 178 (18.2) | |

| 85 plus | 7007 (25.0) | 13 943 (24.9) | |

| Year of index date | |||

| 1987-94 | 2702 (9.6) | 5396 (9.6) | 1.000 |

| 1995-99 | 2734 (9.8) | 5464 (9.8) | |

| 2000-04 | 11 228 (40.1) | 22 430 (40.1) | |

| 2005-10 | 11 368 (40.6) | 22 671 (40.5) | |

| Townsend score (quintiles) | |||

| 1 | 2385 (8.5) | 4767 (8.5) | 1.000 |

| 2 | 2305 (8.2) | 4597 (8.2) | |

| 3 | 2341 (8.4) | 4673 (8.4) | |

| 4 | 2267 (8.1) | 4520 (8.1) | |

| 5 | 1709 (6.1) | 3407 (6.1) | |

| Unknown | 17 025 (60.7) | 33 997 (60.8) | |

| Known drug exposure before index date | |||

| Oestrogen in oral contraceptives | 145 (0.5) | 265 (0.5) | 0.391 |

| Progestogen without oestrogen in oral contraceptives | 177 (0.6) | 412 (0.7) | 0.086 |

| Oestrogen in hormone replacement therapy | 3947 (14.1) | 8547 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Metformin | 2547 (9.1) | 2309 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 12 460 (44.4) | 17 034 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| Drugs that could affect development of gynaecomastia | 9874 (35.2) | 10 918 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 15 718 (56.1) | 30 571 (54.6) | <0.001 |

| Steroids | 6988 (24.9) | 8095 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Known medical history before index date | |||

| Benign breast disease | 161 (0.6) | 382 (0.7) | 0.220 |

| Other cancers | 4312 (15.4) | 7751 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 6653 (23.7) | 6990 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 12 188 (43.5) | 5292 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 16 067 (57.3) | 29 051 (51.9) | <0.001 |

| Family history of breast cancer | 215 (0.8) | 539 (1.0) | 0.005 |

| Body mass index | |||

| Unknown | 6261 (22.3) | 11 181 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| 7.8-<20.3 | 2152 (7.7) | 4512 (8.1) | |

| 20.3-<22.1 | 1823 (6.5) | 4825 (8.6) | |

| 22.1-<23.5 | 1708 (6.1) | 4946 (8.8) | |

| 23.5-<24.8 | 1797 (6.4) | 4863 (8.7) | |

| 24.8-<26.0 | 1820 (6.5) | 4861 (8.7) | |

| 26.0-<27.4 | 1984 (7.1) | 4640 (8.3) | |

| 27.4-<29.1 | 2079 (7.4) | 4583 (8.2) | |

| 29.1-<31.2 | 2310 (8.2) | 4338 (7.8) | |

| 31.2-<34.6 | 2614 (9.3) | 4046 (7.2) | |

| ≥34.6 | 3484 (12.4) | 3166 (5.7) | |

| Alcohol consumption (units/week) | |||

| Unknown | 10 703 (38.2) | 20 997 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| 0 | 10 482 (37.4) | 18 525 (33.1) | |

| 1 | 1975 (7.0) | 4220 (7.5) | |

| 2-4 | 1883 (6.7) | 4939 (8.8) | |

| 5-10 | 1730 (6.2) | 4610 (8.2) | |

| >10 | 1259 (4.5) | 2670 (4.8) | |

| No of drug classes prescribed in year before index date | |||

| 0-2 | 2629 (9.4) | 18 624 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| 3-5 | 10 056 (35.9) | 21 628 (38.6) | |

| 6-8 | 10 517 (37.5) | 12 398 (22.2) | |

| ≥9 | 4830 (17.2) | 3311 (5.9) | |

Risk of breast cancer

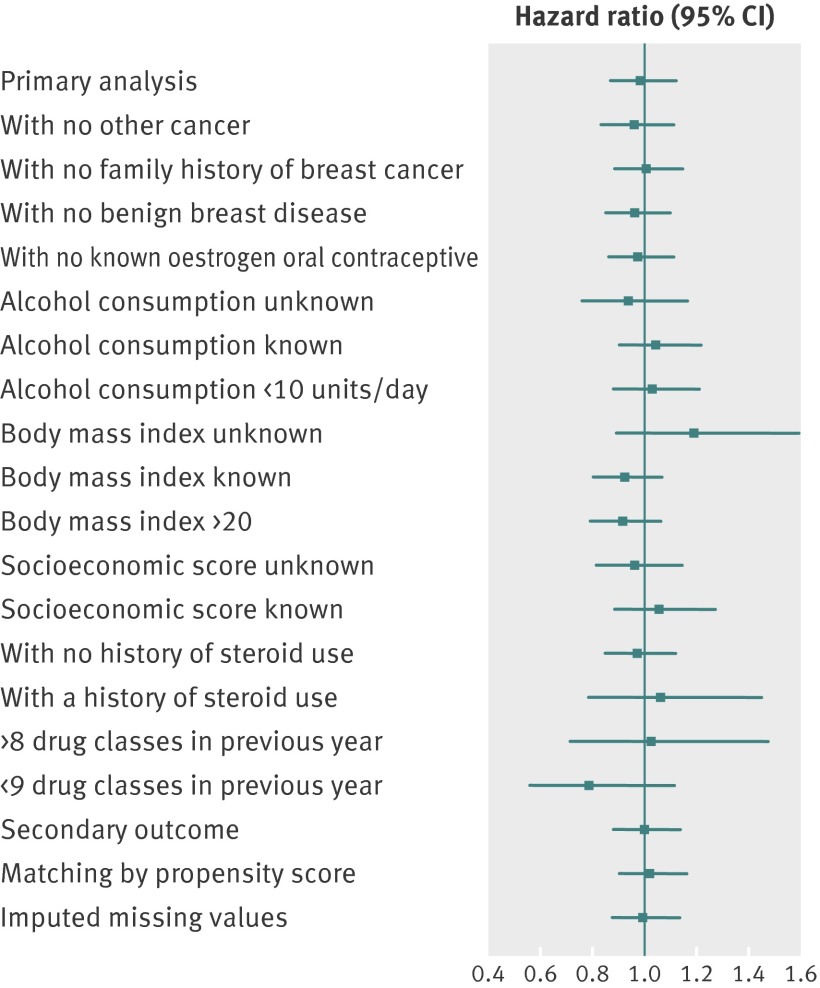

We found no association between spironolactone use and risk of breast cancer in our study population of women aged 55 years or more. The exposed cohort of 28 032 patients and control cohort of 55 961 patients had unadjusted incidence rates of 0.39% and 0.38% per year, respectively. In the primary analysis, the hazard ratio in the exposed cohort versus the control cohort was 0.99 (95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.12). The significant risk factors in this analysis were a family history of breast cancer (3.87, 2.91 to 5.14), a history of other cancers (1.64, 1.44 to 1.87), exposure to multiple drug classes (1.04 per additional class, 1.02 to 1.06), and exposure to steroids (0.78, 0.65 to 0.92).

Subgroup analyses did not show any group of patients in whom spironolactone was a significant risk factor for breast cancer (fig 3). Excluding breast cancer in situ (40 (3%) cases) also resulted in hazard ratios for spironolactone exposure close to 1, as did an analysis using a different control cohort constructed using propensity scores on a subset of the covariates. We found no evidence of a spironolactone dose response relation to risk in the exposed cohort.

Fig 3 Risk of breast cancer in spironolactone users versus non-users, adjusted for significant covariates.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, spironolactone use was not associated with any increase in risk of new breast cancer in women in the UK aged over 55 years with no previous history of breast cancer. Both breast cancer incidence and the use of spironolactone increases with age, hence our choice of study population, because it included those patients most likely to be prescribed spironolactone and also those most likely to develop breast cancer. We cannot comment on whether spironolactone use in younger women or in men has any association with breast cancer from these results. However, only two men within the General Practice Research Database had both a diagnosis of breast cancer and a history of exposure to spironolactone, suggesting that an increased risk of male breast cancer with exposure to spironolactone was unlikely, although the small number of cases makes any study infeasible.

We looked at all incident breast cancers as our primary outcome and all incident breast cancers excluding breast cancers in situ as our secondary outcome, since in situ neoplasia could have a different pathophysiology. However, we found no association between spironolactone use and breast cancer for either outcome.

Comparison with other studies

This study adds to the findings of an earlier cohort study reporting no association between spironolactone use and breast cancer risk. The most recent International Agency for Research on Cancer monograph on spironolactone summarises the known human and animal toxicity data, including studies investigating associations between spironolactone and other cancers.17 Administration of high dose spironolactone to rats increased thyroid follicular cell adenomas and Leydig cell testicular tumours, but reduced the incidence of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene induced mammary tumours. In one cohort study in humans, spironolactone was associated with an excess risk of pharyngeal cancer, whereas a case-control study found no association with thyroid cancer and five case-control studies found that potassium sparing diuretics were not clearly identified as a risk factor for renal cell carcinoma independently of hypertension. Further work with the General Practice Research Database could revisit whether spironolactone use is associated with increased risk of any other types of cancer, particularly those with a hormonal basis such as prostate cancer and thyroid cancer.

Indications for spironolactone have changed in the last few years since earlier observational studies were done, with increasing use in women with hypertension and heart failure and long term use of lower doses. Recent observational studies investigating associations between antihypertensive treatments and breast cancer risk have failed to include spironolactone as a separate variable. For example, a previous study in the General Practice Research Database found no increased risk of breast cancer with captopril and various other antihypertensive agents but spironolactone was not specifically included, perhaps because it is an unlicensed treatment for hypertension in the UK.18

Similarly, a Danish cohort study found no association between breast cancer risk and the use of any antihypertensive treatment or of individual classes of antihypertensive drug (diuretics, β blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II antagonists).19 Conversely, a case-control study in the United States found an association between diuretic use and breast cancer risk.20 However, again in these studies, spironolactone use was not specifically examined. One study found a slight increase in risk of breast cancer associated with use of potassium sparing diuretics, but this category included both spironolactone and amiloride use.21 In addition, some studies have linked hypertension itself to risk of breast cancer whereas others have found no association.22

Strengths and limitations

The General Practice Research Database includes a broad section of patients from the primary care setting including a wide geographical and socioeconomic distribution. Therefore, our results should be largely generalisable to the postmenopausal female population in the UK. However, because the study had an observational design, all potential confounding factors might not have been fully controlled for, despite matching on some and adjusting for others. Although we found no link between incident breast cancer and spironolactone exposure in this study, we did not look at other outcomes and therefore cannot comment on the general safety of spironolactone in women older than 55 years from our data.

Other limitations of this study could include the accuracy of coding for the exposure, outcome, and covariates; and missing data and confounding issues. Random errors were most likely to arise from coding errors in the database, but these errors were probably similar in both the exposed and unexposed cohorts. The codes used for the study were crosschecked by the research team, which included a breast cancer specialist and clinical pharmacologists. Ideally, we would like to check the coding of outcomes for study patients with UK Cancer Registry data.

Some risk factors for breast cancer (such as family history, genetic abnormalities, information on breast feeding and parity, age at menarche and menopause, and use of complementary and recreational medications) were either unavailable or poorly recorded in the General Practice Research Database and therefore of limited use. However, we included all relevant covariates for which data were available in our analyses. We used sensitivity analyses to resolve potential problems of misclassification, bias, and missing data.

Because of the difficulty in differentiating true recurrence of breast cancer from re-reporting of previous breast cancer in the records of the General Practice Research Database, we could not do a sufficiently robust analysis of the hazards of spironolactone in the 1340 women with a history of breast cancer. However, accepting these limitations, we have undertaken a matched cohort analysis in these patients with prevalent breast cancer and judged the risk of recurrence as best as we could. The adjusted hazard ratio was 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.64 to 1.21), suggesting no increase in recurrence rates in women with previous breast cancer exposed to spironolactone. Further research in this area should use more detailed breast cancer databases.

What is already known on this topic

Spironolactone use has increased substantially in recent years for conditions such as heart failure and resistant hypertension

The drug has progestogenic, antiandrogenic, and other less well defined effects on steroid receptors

However, there is concern that the drug could increase the risk of breast cancers and other cancers in humans

What this study adds

No increase in breast cancer risk was seen in women older than 55 years and with no history of breast cancer, after exposure to spironolactone treatment

Contributors: All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in design of the study, analysis and interpretation of results, and preparation and revision of the manuscript. IM is the guarantor for the study.

Funding: No specific funding was received for this study. The study was sponsored by the University of Dundee.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: study sponsorship by the University of Dundee; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: None required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e4447

References

- 1.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, et al. The effects of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. Guideline CG127. 2011. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG127.

- 3.Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JF, et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV. J Hum Hypertens 2004;18:139-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. Spironolactone: no longer for hypertension. Drug Ther Bull 1988;26:88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.British National Formulary No 62. 2011. http://bnf.org/bnf/bnf/current/2371.htm?q=spironolactone&t=search&ss=text&p=1#_hit.

- 6.Gardiner P, Schrode K, Quinlan D, Martin BK, Boreham DR, Rogers MS, et al. Spironolactone metabolism: steady-state serum levels of the sulfur-containing metabolites. J Clin Pharmacol 1989;29:342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy HK, Ménard J, White WB, Young WF Jr, Williams GH, Williams B, et al. A double-blind, randomized study comparing the antihypertensive effect of eplerenone and spironolactone in patients with hypertension and evidence of primary aldosteronism. J Hypertens 2011;29:980-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loube SD, Quirk RA. Breast cancer associated with administration of spironolactone. Lancet 1975;1:1428-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stierer M, Spoula H, Rosen HR. Breast cancer in the male [abstract only]. Onkologie 1990;13:128-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selby JV, Friedman GD, Fireman BH. Screening prescription drugs for possible carcinogenicity: eleven to fifteen years of follow-up. Cancer Res 1989;49:5736-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jick H, Armstrong B. Breast cancer and spironolactone. Lancet 1975;2:368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong B, Stevens N, Doll R. Retrospective study of the association between use of rauwolfia derivatives and breast cancer in English women. Lancet 1974;2:672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Reserpine and breast cancer. Lancet 1974;2:669-71.4142955 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danielson DA, Jick H, Hunter JR, Stergachis A, Madsen S. Nonestrogenic drugs and breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1982;116:329-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year followup study. J Cutan Med Surg 2002;6:541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walley T, Mantgani A. The UK General Practice Research Database. Lancet 1997;350:1097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IARC. IARC monographs, volume 79: spironolactone. P319-337. 2012. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol79/mono79-13.pdf.

- 18.Gonzalez-Perez A, Ronquist G, Rodriguez LAG. Breast cancer incidence and use of antihypertensive medication in women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fryzek JP, Poulsen AH, Lipworth L, Pedersen L, Norgaard M, McLaughlin JK, et al. A cohort study of antihypertensive medication use and breast cancer among Danish women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006;97:231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Largent JA, McEligot AJ, Ziogas A, Reid C, Hess J, Leighton N, et al. Hypertension, diuretics and breast cancer risk. J Hum Hypertens 2006;20:727-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li CI, Malone KE, Weiss NS, Boudreau DM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Relation between use of antihypertensive medications and risk of breast carcinoma among women ages 65-79 years. Cancer 2003;98:1504-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goon PKY, Messerli FH, Lip GYH. Hypertension and breast cancer: an association revisited? J Hum Hypertens 2006;20:722-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]