Abstract

Antiangiogenesis therapy has become a vital part of the armamentarium against cancer. Hypertension is a dose-limiting toxicity for VEGF inhibitors. Thus, there is a pressing need to address the associated adverse events so these agents can be better used. The hypertension may be mediated by reduced NO bioavailability resulting from VEGF inhibition. We proposed that the hypertension may be prevented by coadministration with endostatin (ES), an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor with antitumor effects shown to increase endothelial NO production in vitro. We determined that Fc-conjugated ES promoted NO production in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. ES also lowered blood pressure in normotensive mice and prevented hypertension induced by anti-VEGF antibodies. This effect was associated with higher circulating nitrate levels and was absent in eNOS-knockout mice, implicating a NO-mediated mechanism. Retrospective study of patients treated with ES in a clinical trial revealed a small but significant reduction in blood pressure, suggesting that the findings may translate to the clinic. Coadministration of ES with VEGF inhibitors may offer a unique strategy to prevent drug-related hypertension and enhance antiangiogenic tumor suppression.

Inhibiting angiogenesis has proven to be effective in treating diseases dependent on new blood vessel growth. In cancer patients, antiangiogenic agents prolong progression-free survival and improve response rates when used in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy (1). In macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy these agents reduce vision loss (2, 3). Consequently, angiogenesis inhibitors have been approved in 29 countries thus far (4), and new applications continue to be explored.

VEGF is a potent angiogenesis stimulator clinically established as an efficacious target for inhibition. The first Food and Drug Administration-approved angiogenesis inhibitor was bevacizumab (Avastin), a monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody now used to treat several types of cancer (colon, lung, renal, breast) and ocular neovascularization. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm for bevacizumab and other such inhibitors is tempered by the emergence of treatment-limiting adverse cardiovascular effects.

Hypertension is the most common dose-limiting toxicity of VEGF inhibitors (5–9). Incidence ranges from 15% to 60%, depending on drug- and patient-related factors still being defined (10–14). Early and aggressive initiation of antihypertensive therapy can help maintain the treatment schedule (15) and reduce complications (16, 17). However, baseline blood pressures (BP) often are not reestablished (18). Further, it appears that nearly all patients experience some increase in BP, even if not frank hypertension (19). This finding is concerning, given that changes in BP of as little as 5 mm Hg can significantly impact mortality (20). As life expectancy for patients maintained on these newer antitumor agents continues to improve, complications from the accompanying chronic BP elevations will likely accumulate.

One widely held explanation for angiogenesis inhibitor-associated hypertension is based on the role of VEGF in NO regulation. NO is a potent vasodilator that plays a critical role in BP control. VEGF stimulates endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), resulting in NO production and lower BP (21, 22). Inhibiting VEGF in animal studies reduces eNOS expression, leading to vasoconstriction and hypertension (23). In patients, VEGF infusion causes rapid NO release and hypotension (24).

Endostatin (ES), a fragment of collagen XVIII on chromosome 21, is an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor (25, 26). This 183-amino acid fragment causes tumor regression in a number of animal models (27, 28). Although the molecular pathways are not fully defined, major effects of ES signaling include inhibition of endothelial cell migration and survival and angiogenesis. In addition, ES induces NO release by cultured endothelial cells and relaxation of ex vivo vascular rings (29, 30). Down syndrome patients have an extra copy of chromosome 21 and a negligible incidence of solid tumors (31). Although several genes likely contribute to this cancer protection (32), it is intriguing to note that these patients have ES levels 1.6 times higher than those of the general population (33). Further, their BP is lower than age-matched controls (34, 35). These data suggested to us that ES may enhance the antiangiogenic benefits and lessen the hypertensive effects of VEGF inhibition. Such a finding would offer an approach to improve tolerance to VEGF inhibitors, enabling long-term treatment with reduced risk of cardiovascular adverse events.

Here we show that murine Fc-conjugated ES lowers BP in mice via an NO-mediated mechanism and blocks the hypertensive response to anti-VEGF antibodies. Further, we found a small but significant reduction in BP in patients treated with ES as part of a clinical trial, suggesting that the finding in mice may be translatable. These results support further investigation into antitumor effects of combined therapy.

Results

ES Lowers BP in C57BL/6 Mice.

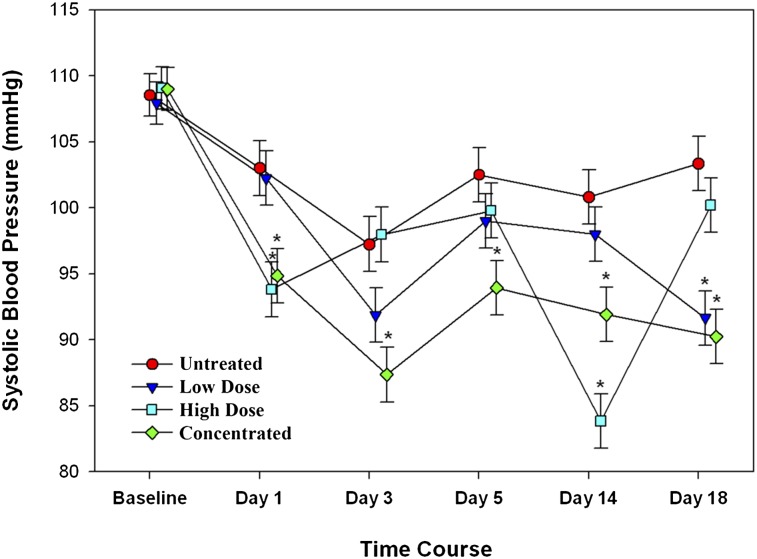

Normotensive C57BL/6 mice were treated with ES at various doses and schedules, and BP responses were compared with vehicle (saline)-treated controls. All mice were injected daily for 5 d with either ES or saline; after a 2-d intervening break, the cycle was repeated. A slight reduction in BP at the onset of the study was noted in all the groups, likely resulting from further acclimation. Thereafter, BP in the control group remained unchanged, whereas BP of the ES-treated groups decreased in relation to dose and schedule (Fig. 1). Mice receiving ES (4 mg/kg) biweekly had the smallest BP reductions, with nadirs of ∼10 mm Hg below controls on the day following treatment (e.g., days 1 and 18). BP rebounded to about 5 mm Hg below controls between drug doses. Mice treated with ES (4 mg/kg) for 5 d consecutively exhibited the most stable reduction in BP, to an average of 10 mm Hg below controls, and did not rebound during the 2-d treatment breaks. The last group, which received a cumulative weekly dose of 20 mg/kg as a single, concentrated bolus and had the most significant decline in BP, to nearly 20 mm Hg below control following drug injections. The BP then recovered to baseline before the next dose.

Fig. 1.

Murine Fc-ES resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in systolic BP in C57BL/6 mice. The low-dose group received 4 mg/kg, 2 d/wk (on days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 17) and had the smallest decrease in BP. The high-dose group received 4 mg/kg, 5 d/wk (on days 0–4, 7–11, and 14–18) and had the most stable BP reduction. The concentrated-dose group received the cumulative high weekly dose of 20 mg/kg administered in a single concentrated bolus once a week (on days 0, 7, and 14) and had the greatest declines in BP on the days following treatment; BP levels recovered thereafter. *P < 0.05.

Endogenous and Exogenous ES Increases NO.

Physiologic concentrations of ES have been shown to increase NO production in endothelial cells and to decrease vascular tone in ex vivo studies (29). We found that murine Fc-ES significantly increased nitrite production in microvascular (MS1) endothelial cells (P = 0.005) (Fig. S1A) and smooth muscle cells (P = 0.0004) (Fig. S1B) compared with the matched vehicle (saline) controls. Elevated NO production by these vascular cells in response to ES in vivo would lead to lower BP.

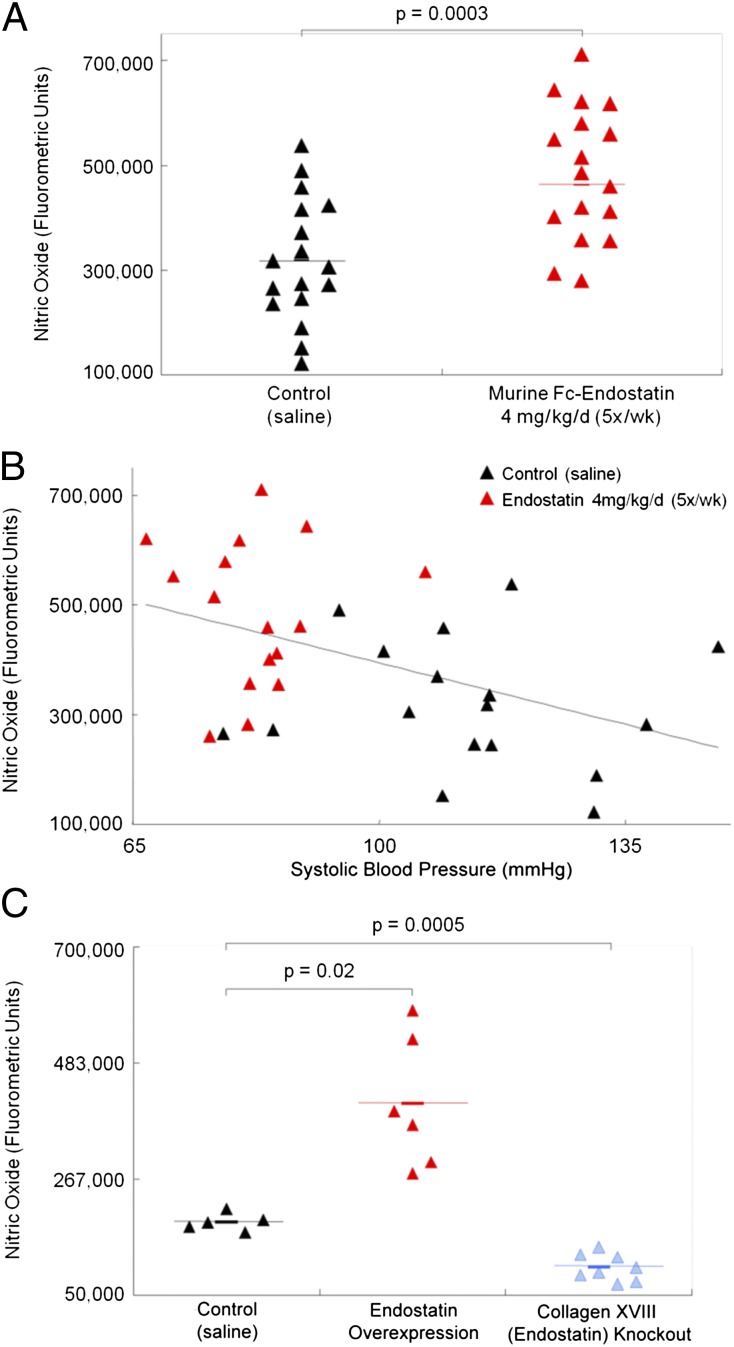

Serum nitrate levels were significantly higher in mice treated with ES (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 2A) than in controls, indicating higher circulating NO levels. Nitrate levels related inversely to systolic BP, which segregated the ES and control groups (Fig. 2B): Nitrate levels were higher and BP was lower in ES-treated mice than in controls.

Fig. 2.

Murine Fc-ES administration (4 mg/kg, 5 d/wk) is associated with (A) higher circulating nitrate levels (a measure of NO) and (B) lower systolic BP in C57BL/6 mice as compared with saline-treated controls. (C) Circulating NO levels were higher in ES-overexpressing mice and were lower in collagen XVIII/ES-knockout mice than in wild-type control mice. These findings correlated NO levels with endogenous and exogenous ES levels.

Nitrate levels also were measured in serum samples from ES-overexpressing mice and collagen XVII-knockout mice. ES is a proteolytic fragment of collagen XVIII and therefore is absent in the knockout mice. Compared with wild-type controls, nitrate levels were higher in the ES-overexpressing mice (P = 0.02) and lower in the collagen XVIII-knockout mice (P = 0.0005) (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these findings correlate circulating NO levels with endogenous and exogenous ES levels.

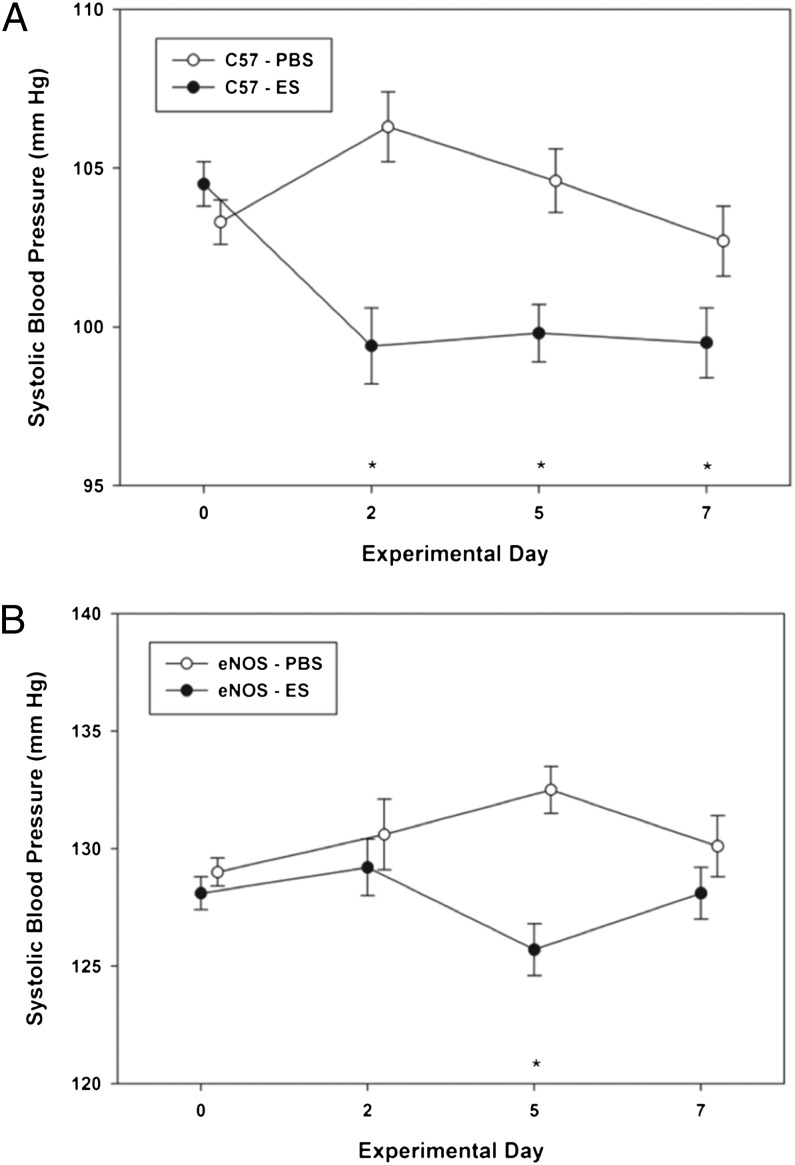

ES Does Not Alter BP in eNOS-Knockout Mice.

eNOS-knockout mice were treated with ES at 4 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1 for 5 d followed by a 2-d break. As has been reported previously, the eNOS-knockout mice were relatively hypertensive, with baseline systolic BP of nearly 130 mm Hg compared with 105 mm Hg typically seen in wild-type C57BL/6 mice (36).

The interaction test was significant for both C57BL/6 mice (F = 8.81, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A) and eNOS-knockout mice (F = 4.06, P = 0.007) (Fig. 3B), indicating that systolic BP showed a different profile from baseline through day 7 for animals treated with PBS and those treated with ES. For C57BL/6 mice, BP was unchanged with PBS treatment (F = 2.42, P = 0.063) and decreased significantly with ES (F = 10.17, P < 0.001) on days 2, 5, and 7, compared with baseline (all P < 0.001). In contrast, in eNOS-knockout mice, ES had no significant effect on BP (F = 1.92, P = 0.123). There was a small but significant increase in systolic BP over baseline on day 5 (F = 2.91, P = 0.033) in mice treated with PBS. The findings suggest a role for eNOS in ES-induced BP reductions.

Fig. 3.

ES (4 mg/kg, 5d/wk) caused a significant decrease in systolic BP throughout the treatment period in wild-type C57BL/6 mice (A) but only on day 5 in eNOS-knockout mice (B).

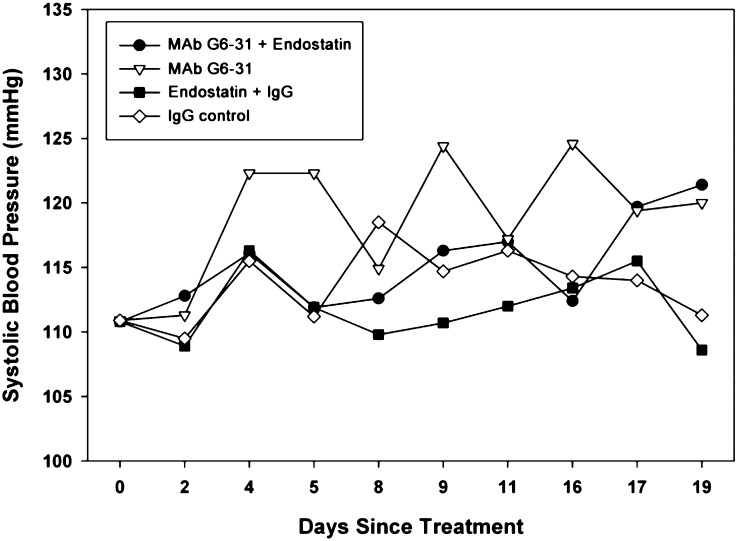

ES Prevents Anti-VEGF Antibody-Induced BP Elevations in C57BL/6 Mice.

Normotensive C57BL/6 mice were treated with anti-murine VEGF antibody, MAb G6-31 (5 mg/kg, 2×/wk on days 1, 4, 8, 11, and 15) alone or in combination with ES (4 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1, 5 d/wk) (Fig. 4). BP curves in the group treated with MAb G6-31 alone revealed significant spikes on the days following treatment. These elevations recovered less and less with each subsequent dose, resulting in a steady increase in baseline BP. ES prevented the BP spikes after MAb G6-31 treatments, although the gradual elevation in baseline pressure still occurred. BP in the IgG control group (5 mg/kg, 2×/wk on days 1, 4, 8, 11, and 15) increased slightly above baseline. BP in the IgG + ES control group did not vary significantly from baseline. The absence of a BP decrease in the ES group in this study may result from the coadministration of IgG. Correlations between hypertension and elevated levels of serum IgG have been reported (37). IgG may have contributed to the steady increase in baseline BP in all of the groups.

Fig. 4.

ES prevented the marked BP elevations that accompany VEGF inhibition. Normotensive mice treated with anti-murine VEGF antibody MAb G6-31 (5 mg/kg on days 1, 4, 8, 11, and 15) developed significant spikes in BP on the day following treatment. Simultaneous ES treatment (4 mg/kg, 5 d/wk) prevented these BP spikes. Control mice received IgG (5 mg/kg on days 1, 4, 8, 11, and 15) or IgG + ES (4 mg/kg, 5 d/wk). A gradual increase in baseline BP occurred in both control groups and may be related to IgG.

ES Limits Anti-VEGF Antibody-Induced Cardiosuppression in Mice.

Echocardiography was used to evaluate the cardiac function of mice treated with MAb G6-31 with and without ES compared with controls (ES + IgG or IgG alone) on days 40 and 47 of the study above (Table S1). There was no significant difference in chamber dimensions (ventricular chamber and septal and posterior wall dimensions during systole and diastole) among the groups or over time. The percent of fractional shortening (FS), a measure of contractility, also was within normal limits and was similar among the groups on day 40 (P = 0.99). However, on day 47, FS was reduced in mice receiving MAb G6-31 alone (P = 0.03) but remained unchanged in animals on dual treatment (MAb G6-31 + ES), resulting in a significant difference between the groups (P = 0.01). Both control groups of mice receiving IgG had reductions in FS on day 47. Although FS was less reduced for mice treated with IgG + ES, the difference between the two groups was not significant (P = 0.19). Percents of FS on day 47 were similar among the mice treated with MAb G6-31 and both the IgG control groups (IgG alone, P = 0.49; ES + IgG, P = 0.18).

BP Decreases in ES-Treated Patients.

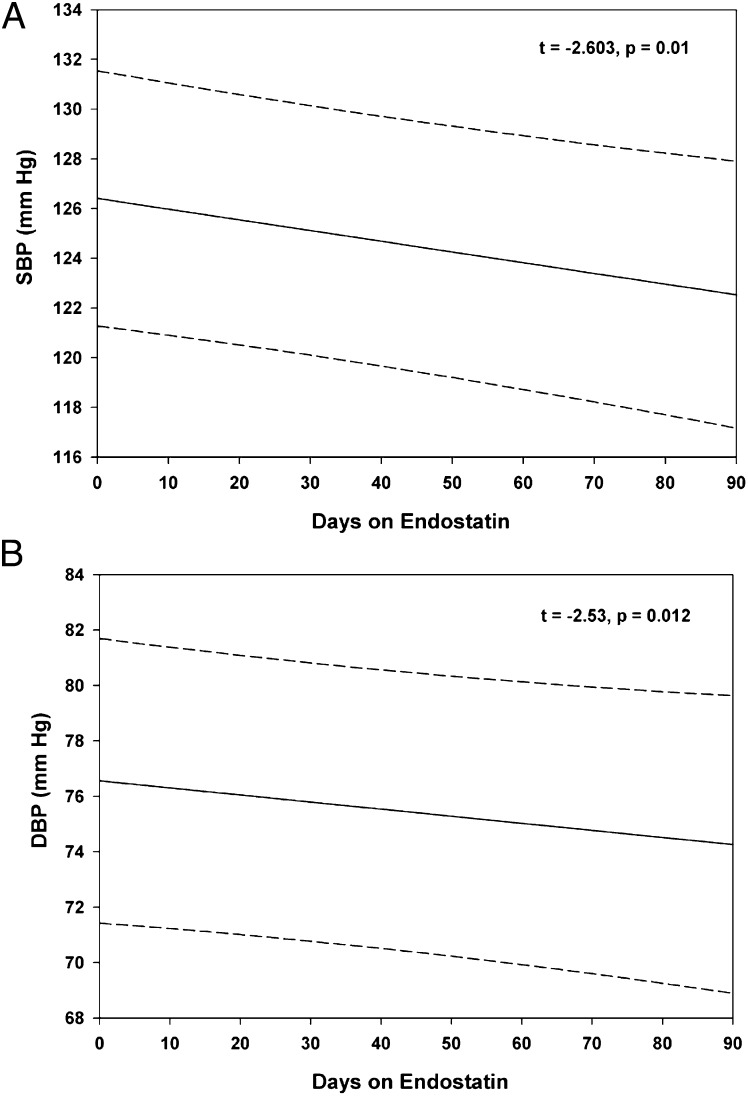

BP data were obtained from a phase II clinical trial of ES in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. The BP data from the first 3 mo of the study (three cycles of ES) were analyzed retrospectively, revealing a small but significant decrease in both systolic BP (t = −2.60, P = 0.01) (Fig. 5A) and diastolic BP (t = −2.53, P = 0.012) (Fig. 5B) in treated patients compared with their pretreatment pressures. On average, every 10 d on ES was associated with a decrease in systolic BP of 0.43 mm Hg and a decrease in diastolic BP of 0.26 mm Hg. The confidence intervals are wide, given the variability among patients, although the trend for both BPs is clearly downward with longer time on ES.

Fig. 5.

ES decreased BP in patients. BP was recorded from 42 patients treated with rhES as part of a phase I clinical trial for neuroendocrine cancer. Measurements from the first three cycles show a small but significant decrease in both systolic BP (A) and diastolic BP (B). Predicted values are indicated by solid lines; 95% confidence intervals for individual patients are indicated by dashed lines.

Discussion

VEGF-mediated angiogenesis is central to tumor progression and has become a therapeutic target for anticancer treatment (38, 39). Angiogenesis inhibition via anti-VEGF antibodies (bevacizumab) in combination with chemotherapy has prolonged progression-free survival and response rates in patients with advanced breast, colon, and lung cancers (4, 6, 7, 40, 41). This success has directed focus to the side effects of these agents to enable full and indefinite use.

Unanticipated cardiovascular adverse events of bevacizumab and other antiangiogenesis agents have been treatment limiting. The most prevalent of these adverse events is hypertension, which commonly is defined as >140/90 or >150/100 mm Hg in clinical trials (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0; http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm) (42). Identifying an agent that can mitigate the hypertension and augment the antiangiogenic effects of VEGF inhibitors would address this pressing clinical need. ES may be uniquely suited for this purpose, being an angiogenesis inhibitor shown to increase NO bioavailability in vitro (27–30).

We found that ES significantly lowered BP in normotensive mice by up to ∼10 mm Hg in a dose- and schedule-dependent fashion (Fig. 1). Despite the long drug half-life (weeks), daily administration rather than a single weekly bolus was needed to achieve a sustained reduction in BP. This result is in contrast to the treatment schedule that is effective for tumor suppression, suggesting that a different mechanism may be responsible (43). A NO-mediated mechanism is supported by our findings that ES increased NO release from endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vitro (Fig. S1). These cell types regulate vascular tone and BP. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that ES induces NO release by cultured endothelial cells and relaxation of ex vivo vascular rings (29, 30). Further, we show that circulating nitrate levels were higher in ES-treated mice than in controls (Fig. 2). The association between ES and NO in vivo is strengthened further by our finding that nitrate levels were higher in plasma from ES-overexpressing mice and were lower in collagen XVIII-knockout mice than in wild-type animals.

ES did not reduce BP significantly in eNOS-knockout mice (Fig. 3), implicating eNOS as a mediator of this hemodynamic effect. This result is consistent with other studies showing that short-term exposure of bovine aortic endothelial cells to ES induced events associated with eNOS activation (30). Using single-cell measurements, Wenzel et al. (29) showed that ES induced increases in NO production by human and murine endothelial cells that were blocked by an eNOS inhibitor. Ex vivo studies showing vessel relaxation suggested that this mechanism might be physiologically relevant. Our in vivo studies support that supposition. In contrast, Urbich et al. (44) demonstrated that ES interfered with VEGF-induced eNOS phosphorylation at Ser-1177; this interference would be expected to reduce NO bioavailability. The dose and duration of ES exposure may be critical in determining the outcome.

We then determined whether the hemodynamic effects of ES could be used to combat the hypertension induced by VEGF inhibitors. The mechanisms regulating this adverse event have yet to be elucidated. However, there is mounting evidence that disruption of VEGF-mediated NO bioavailability plays a significant role. VEGF causes release of NO and up-regulates eNOS RNA and protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (21). Disrupting this pathway with a VEGF inhibitor would be expected to increase vessel tone and elevate BP. ES may neutralize this process via counteracting effects on the same pathway.

We found that administration of an anti-VEGF antibody resulted in two superimposed patterns of BP increase in mice (Fig. 4). Transient spikes in BP to ∼125 mm Hg occurred twice weekly, after each treatment, confirming that VEGF inhibition significantly elevates BP. The time course of the spikes relative to drug dosing offers insight into study designs to ensure capture of such findings. Whether this response occurs in patients would be important and easily obtained information. In addition, over the 19-d study there was a gradual increase of ∼8 mm Hg above baseline to just under 120 mm Hg. The two patterns of BP increase may indicate multiple effects from VEGF inhibition. For example, NO reduction can cause transient functional (vasoconstriction) changes acutely and persistent structural (e.g., vascular remodeling, rarefaction) changes when chronic. The implication is that the hypertension may be less reversible and more challenging to manage for patients on long-term antiangiogenic therapy.

Our findings are consistent with the findings of Facemire et al. (23), who demonstrated that mice treated with an anti-VEGFR2 receptor antibody had a 10 mm Hg increase in BP that was abolished with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester. VEGFR2 modulates eNOS production of NO through multiple signaling pathways (45, 46). The hypertension in their study was associated with significant reductions in the expression of endothelial and neuronal NO synthases in the kidney; such reductions would be expected to reduce NO bioavailability.

Combination treatment with ES and anti-VEGF antibody completely abolished the dramatic BP spikes seen with the antibody alone. Small but significant reductions in both systolic and diastolic BP in 42 patients treated with ES in clinical trials suggests that this mechanism may translate to patients (Fig. 5). The results from the clinical trial showing a statistically significant decrease in BP from ES treatment, in combination with the animal studies, suggest that ES is likely sufficient to prevent the hypertensive spikes induced by anti-VEGF antibody. It is hoped that a prospective clinical trial will be carried out to validate this finding

The ES molecule used in prior clinical trials had a short half-life (∼2 h) with variable potency resulting from difficult synthesis and molecular instability. Development of a recombinant human ES conjugated to the Fc domain of IgG has made such translation feasible (43). The half-life of Fc-ES is measurable in weeks, similar to that of bevacizumab. The estimated doses needed, based on preclinical studies, are orders of magnitude lower than the clinically tested drug because of markedly improved potency. The Fc-conjugated form of ES is more suitable for clinical trials.

Antiangiogenic agents have been shown to reduce cardiac function (18) in addition to hypertension. The influence of VEGF and NO on BP potentially could contribute to the reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (47). We found that anti-VEGF antibody, MAb G6-31, caused a reduction in fractional shorting after prolonged treatment that was prevented by ES (Fig. 5). The reduction cannot be fully attributed to VEGF inhibition, however, because it also occurred in control mice treated with IgG. This finding may reflect an effect of the immunoglobulins, which have been implicated in cardiac dysfunction in dilated cardiomyopathy patients (48). Although immunoglobulins are presumed to be primarily cardiac autoantibodies, the Fc part of IgG molecules may cause negative inotropic effects in cardiac myocytes, as well (49).

Our results suggest that ES increases NO production and/or availability, reduces BP in vivo, and prevents hypertension induced by VEGF inhibition. These finding suggest that combination therapy with these agents may augment the antitumor effects while preventing the adverse cardiovascular effects. Such a strategy would be expected to improve patient tolerance to these highly effective agents and further advance the paradigm shift in cancer management toward a chronic disease.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care.

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Children’s Hospital, Boston, and were in compliance with institutional guidelines. Unless otherwise specified, 16-wk-old male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used. Mice were caged in groups of three to five and were fed animal chow and water ad libitum.

BP Measurements.

BP was measured using noninvasive tail-cuff systems to avoid surgical manipulation. The IITC 12M179 12-channel system (IITC Life Science, Inc.) was used for the ES dose study (Fig. 1). Thereafter, studies were conducted using three Kent Coda-6 systems (Kent Scientific) to increase throughput, allowing a larger number of mice to be measured within a 4-h period. Mice were acclimated to the BP systems over several days (50). Baseline BP then was established for each animal as the average of three sets of readings acquired on separate days with no significant difference in the sets of measurements for each mouse.

NO Assay in Mice.

Serum samples were collected from wild-type mice treated with saline (control) or ES (4 mg/kg/d, 5×/wk). Samples from untreated collagen XVIII-knockout mice (51, 52) and ES-overexpressing mice (53) were generously provided by Sandra Ryeom (Children’s Hospital, Boston). The NO assay was performed using a quantitative fluorometric extracellular NO assay (Calbiochem) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma was thawed, filtered using Ultracel 10-kDa cutoff Microcons (Millipore) by centrifugation (0.5 h, 4 °C), and samples were processed in the NO assay. Plates were read using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Victor3 microplate reader (Perkin-Elmer), with excitation at 355 nm and emission at 430 nm.

Retrospective Analysis of BP from Patients Receiving ES.

In a multicenter phase II clinical trial, patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors were treated with recombinant human ES (rhES). Forty-two patients were enrolled in the study from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston), Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston), the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston), or the University of California, San Francisco Comprehensive Cancer Center (San Francisco). The treatment schedule was 30 mg/m2 rhES twice a day with a starting total daily dose of 60 mg/m2 daily without treatment breaks. One cycle was 28 d of treatment. If patients did not reach a steady-state trough level of 300 ng/mL, the daily dose was increased to 90 mg/m2 (54). Three cycles of BP data collected from these patients over 3 mo of continuous treatment were analyzed retrospectively.

Additional methodology is described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Napoleone Ferrara and Dr. Stuart Bunting of Genentech for generously contributing MAb G6-31 and their expertise to these studies and Dr. Louis G. D’Alecy, University of Michigan Medical School, for contributing his expertise in hemodynamic monitoring. We also thank EntreMed for access to the ES clinical trial BP data.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

2Deceased January 14, 2008.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1203275109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goff MJ, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for previously treated choroidal neovascularization from age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2007;27:432–438. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318042b53f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajappa M, Saxena P, Kaur J. Ocular angiogenesis: Mechanisms and recent advances in therapy. Adv Clin Chem. 2010;50:103–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folkman J. Antiangiogenesis in cancer therapy—endostatin and its mechanisms of action. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JC, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller K, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurwitz H, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandler A, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grothey A, et al. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326–5334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhargava P. VEGF kinase inhibitors: How do they cause hypertension? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1–R5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90502.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escudier B, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, et al. Phase III randomized trial of sunitinib malate (SU11248) versus interferon-alpha (IFN-a) as first-line systemic therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:LBA3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veronese ML, et al. Mechanisms of hypertension associated with BAY 43-9006. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1363–1369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu S, Chen JJ, Kudelka A, Lu J, Zhu X. Incidence and risk of hypertension with sorafenib in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:117–123. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langenberg M, et al. Effective strategies for management of hypertension after vascular endothelial growth factor signaling inhibition therapy: Results from a phase II randomized, factorial, double-blind study of cediranib in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6152–6159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozcan C, Wong SJ, Hari P. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome and bevacizumab. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:980–982, discussion 980–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen JA, Adlakha A, Bergethon PR. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome after bevacizumab/FOLFIRI regimen for metastatic colon cancer. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1475–1478. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu TF, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphreys BD, Atkins MB. Rapid development of hypertension by sorafenib: Toxicity or target? Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5947–5949. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barter PJ, et al. ILLUMINATE Investigators Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hood JD, Meininger CJ, Ziche M, Granger HJ. VEGF upregulates ecNOS message, protein, and NO production in human endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H1054–H1058. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facemire CS, Nixon AB, Griffiths R, Hurwitz H, Coffman TM. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 controls blood pressure by regulating nitric oxide synthase expression. Hypertension. 2009;54:652–658. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry TD, et al. VIVA Investigators The VIVA trial: Vascular endothelial growth factor in Ischemia for Vascular Angiogenesis. Circulation. 2003;107:1359–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061911.47710.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh SP, et al. Isolation and sequencing of cDNAs for proteins with multiple domains of Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeats identify a distinct family of collagenous proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4229–4233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehn M, Pihlajaniemi T. Alpha 1(XVIII), a collagen chain with frequent interruptions in the collagenous sequence, a distinct tissue distribution, and homology with type XV collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4234–4238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehm T, Folkman J, Browder T, O’Reilly MS. Antiangiogenic therapy of experimental cancer does not induce acquired drug resistance. Nature. 1997;390:404–407. doi: 10.1038/37126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Reilly MS, et al. Endostatin: An endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenzel D, et al. Endostatin, the proteolytic fragment of collagen XVIII, induces vasorelaxation. Circ Res. 2006;98:1203–1211. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219899.93384.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Harris MB, Venema VJ, Venema RC. Endostatin induces acute endothelial nitric oxide and prostacyclin release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down’s syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: A population-based study. Lancet. 2002;359:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek KH, et al. Down’s syndrome suppression of tumour growth and the role of the calcineurin inhibitor DSCR1. Nature. 2009;459:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature08062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richards BW, Enver F. Blood pressure in Down’s syndrome. J Ment Defic Res. 1979;23:123–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1979.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergers G, Javaherian K, Lo KM, Folkman J, Hanahan D. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on multistage carcinogenesis in mice. Science. 1999;284:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zorick TS, et al. High serum endostatin levels in Down syndrome: Implications for improved treatment and prevention of solid tumours. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:811–814. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang PL, et al. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377:239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khraibi AA. Association between disturbances in the immune system and hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4:635–641. doi: 10.1093/ajh/4.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparini G, et al. Clinical relevance of vascular endothelial growth factor and thymidine phosphorylase in patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with either adjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy. Cancer J Sci Am. 1999;5:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller KD, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of ZD6474, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3369–3376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miles D, et al. Phase III study of bevacizumab plus docetaxel for the first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3239–3247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert N, et al. RIBBON-1: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1252–1260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mir O, Ropert S, Alexandre J, Goldwasser F. Hypertension as a surrogate marker for the activity of anti-VEGF agents. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:967–970. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee TY, et al. Linking antibody Fc domain to endostatin significantly improves endostatin half-life and efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1487–1493. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urbich C, et al. Dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase contributes to the anti-angiogenic effects of endostatin. FASEB J. 2002;16:706–708. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0637fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanimoto T, Jin ZG, Berk BC. Transactivation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor Flk-1/KDR is involved in sphingosine 1-phosphate-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42997–43001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gélinas DS, Bernatchez PN, Rollin S, Bazan NG, Sirois MG. Immediate and delayed VEGF-mediated NO synthesis in endothelial cells: Role of PI3K, PKC and PLC pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:1021–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verheul HM, Pinedo HM. Possible molecular mechanisms involved in the toxicity of angiogenesis inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:475–485. doi: 10.1038/nrc2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staudt A, et al. Potential role of autoantibodies belonging to the immunoglobulin G-3 subclass in cardiac dysfunction among patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2002;106:2448–2453. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036746.49449.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staudt A, Eichler P, Trimpert C, Felix SB, Greinacher A. Fc(gamma) receptors IIa on cardiomyocytes and their potential functional relevance in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1684–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johns C, Gavras I, Handy DE, Salomao A, Gavras H. Models of experimental hypertension in mice. Hypertension. 1996;28:1064–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.6.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukai N, et al. Lack of collagen XVIII/endostatin results in eye abnormalities. EMBO J. 2002;21:1535–1544. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marneros AG, Olsen BR. Physiological role of collagen XVIII and endostatin. FASEB J. 2005;19:716–728. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2134rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sund M, et al. Function of endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis as endothelium-specific tumor suppressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2934–2939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500180102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kulke MH, et al. Phase II study of recombinant human endostatin in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3555–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.