ABSTRACT

Purpose: To determine the psychometric properties of the 11-item Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) in patients with heterogeneous chronic pain. Methods: The study evaluated test–retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient), cross-sectional convergent construct validity (Pearson product–moment correlation between TSK-11 and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale [PCS] scores at admission), and sensitivity to change of the TSK-11 (area under the receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve) in patients (n=74) with heterogeneous chronic pain. We used two data sets (retrospective, n=56; prospective, n=18). All patients attended the 4-week interdisciplinary chronic pain management programme at Chedoke Hospital, Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, Ontario. Results: The test–retest reliability of the TSK-11 was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.58–0.93), the standard error of measurement was 2.41 (90% CI, 1.47–2.49), and the minimal detectible change score was 5.6. The correlation between TSK-11 and PCS at admission was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.43–0.73). The area under the ROC curve was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.57–0.88). Conclusions: The study results provide evidence for the test–retest reliability, cross-sectional convergent construct validity, and sensitivity to change of the TSK-11 in a population with heterogeneous chronic pain.

Key Words: chronic pain, pain management, reproducibility of results, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK)

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif: Déterminer les propriétés psychométriques des 11 jalons de l'échelle de Tampa de kinésiophobie (TSK-11) chez les patients avec douleur chronique hétérogène. Méthode: L'étude actuelle a évalué la fiabilité test-retest (coefficient de corrélation intraclasse), la validité du construit et la validité convergente croisée (corrélation de Pearson produit–moment entre le score de la TSK-11 et celui de l'échelle des pensées catastrophiques (PCS) à l'admission et la sensibilité au changement de la TSK-11 (section située sous la courbe ROC (caractéristique de fonctionnement du récepteur) chez les patients (n=74) avec douleur chronique hétérogène. Nous avons utilisé deux ensembles de données récoltées de façon rétrospective (n=56) et prospective (n=18). Tous les patients ont suivi le programme interdisciplinaire de quatre semaines pour la gestion de la douleur chronique de l'hôpital Chedoke du Hamilton Health Sciences. Résultats: La fiabilité test-retest de la TSK-11 était de 0,81 (IC de 95 %, 0,58–0,93), l'erreur de mesure normale était de 2,41 (IC de 90 %, 1,47–2,49) et le changement de score minimal détectable était de 5,6. La corrélation entre la TSK-11 et la PCS à l'admission était de 0,60 (IC de 95 %, 0,43–0,73). La section situé sous la courbe ROC était de 0,73 (IC de 95 %, 0.57–0.88). Conclusions: Les résultats de l'étude font la preuve de la fiabilité test-retest, de la validité du construit et de la validité convergente croisée et de la sensibilité au changement dans la TSK-11 chez une population aux prises avec de la douleur chronique hétérogène.

Mots clés : douleur chronique, échelle de Tampa de la kinésiophobie (TSK), gestion de la douleur, reproductibilité des résultats

Research findings suggest that cognitive, affective, and behavioural factors play a role in the aetiology and persistence of chronic pain.1–5 The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain, originally developed in 1983, explains the contribution of these factors in the transition from acute to chronic pain.6 According to this model, fear of pain plays an important role in the onset, development, and maintenance of chronic pain.6,7 More recent research has shown the distinct contributions of pain-related fear, which includes fear of movement/re-injury, catastrophizing, and depression, in predicting pain-related outcomes.8,9 Fear of pain may cause individuals to avoid movement and physical activity, leading to withdrawal from rewarding pursuits such as work, leisure, and family activities to minimize discomfort, pain, and suffering.10 A vicious cycle of catastrophizing, pain-related fear, and avoidant behaviours, as well as depression, may ensue, leading to reduced physical activity, increased disability, and perpetuating pain.7–11

Fear of movement/re-injury, also known as kinesiophobia, is “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or reinjury.”12(p.36) Highly fear-avoidant individuals interpret pain as a sign of harmful bodily processes and any physical activity that results in pain as dangerous.12 In people with chronic pain, this construct has traditionally been measured using the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK),12 a self-report questionnaire consisting of 17 statements rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree; some items are reverse-coded during scoring). The total score can range from 17 to 68; higher scores indicate greater fear of re-injury.12

Higher scores on the TSK are positively associated with catastrophizing,13 depression, and anxiety.14 Now that kinesiophobia has been identified as an important component of chronic pain, the TSK can be used to identify high fear-related beliefs in people with chronic pain as an outcome measure following fear-based interventions, or to evaluate change over time.

To be useful, an outcome measure must possess good psychometric properties such as reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. These properties of the TSK have been examined in populations with chronic low back pain (LBP), acute LBP, neck pain, fibromyalgia, and shoulder pain.13–20 The TSK has good internal consistency (α=0.68–0.80), test–retest reliability up to 50 days (intra-class correlation coefficient [ICC]=0.72), and construct validity (the latter when tested against fear-avoidance beliefs and pain catastrophizing).14–18 The Dutch and Swedish versions of the TSK have good predictive and construct validity, good to excellent test–retest reliability (r=0.64–0.91), and good internal consistency (α=0.70–0.81) in patients with LBP.17–20

In 2005, the original 17-item TSK was revised to create an 11-item version known as the TSK-11, excluding “six psychometrically poor items.”21(p.137) Four items were removed because their responses did not fit the pattern of a normal distribution,21 and two others because they appeared to measure different constructs than the other items.21 The psychometric properties of TSK-11, including internal consistency, test–retest reliability, responsiveness, concurrent validity, and predictive validity, were examined and compared with those of the original TSK in a sample of participants with LBP and were found to be similar.21 However, the TSK-11 has the advantage of being shorter, meaning that it takes less time to complete. The psychometric properties of the TSK-11 in a diverse group of patients with chronic pain (e.g., neck pain, fibromyalgia) in different clinical settings have yet to be investigated.

Our objective in this study, therefore, was to determine test–retest reliability validity (as measured through its association with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, PCS)9 and sensitivity to change (as compared to the Self-Evaluation Scale, SES)22,23 of the TSK-11 in a heterogeneous sample of patients with chronic pain who attended a 4-week interdisciplinary chronic pain management programme.

METHODS

Patient Population and Setting

Our study was conducted in the context of the interdisciplinary, multimodal 4-week outpatient programme at Chedoke Hospital, Hamilton Health Sciences, in Ontario, Canada.

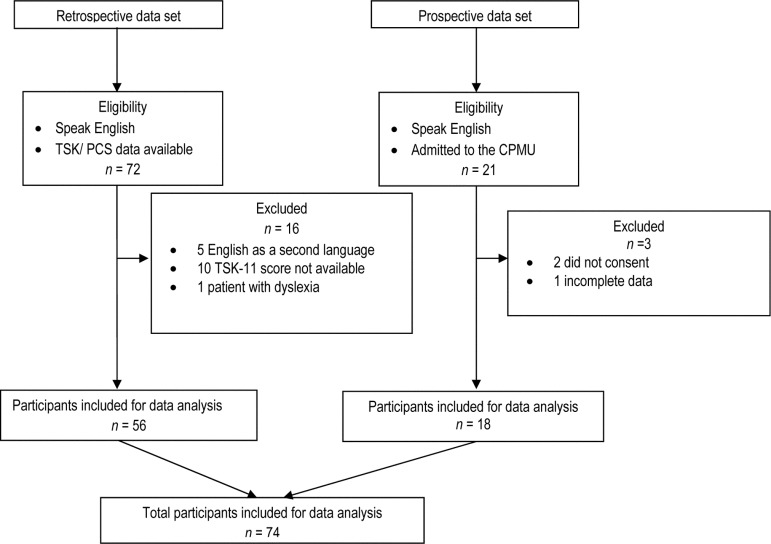

In this programme, which is based on cognitive–behavioural principles, people with chronic pain learn self-management strategies. Our data set comprised two patient samples (see Figure 1). Of 21 consecutive patients admitted to the pain programme between April and June 2010 who could read and understand English and provided informed consent, two declined participation, and one had incomplete data, resulting in a prospective sample size of 18 patients. This prospective sample was used to determine estimates of test–retest reliability. Of 72 consecutive patients admitted between November 2009 and April 2010 who had consented to the use of their anonymized data for research purposes; 16 were excluded because they could not understand English (2), had difficulty reading (1), or had missing data (13), for a final retrospective sample size of 56. Data from the prospective and retrospective samples (n=74) were used to determine validity and sensitivity to change. Ethics approval was obtained by the hospital's Research Ethics Board.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants through the study.

Measures

Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11)

The psychometric properties of the 11-item TSK (TSK-11) have been described by Woby and colleagues.21 The TSK-11 is scored identically to the original version, except that there are no reverse-coded items; the total score ranges from 11 to 44 points, and higher scores signify greater fear of re-injury due to movement.21

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)

The PCS9 is a 14-item self-report questionnaire that describes different thoughts and feelings that a person may experience when encountering pain. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (0=not at all, 4=all the time). Total score ranges from 0 to 56; a higher scores reflects a greater degree of catastrophizing.

Self-Evaluation Scale (SES)

The SES22,23 asks, “To what extent do you think you have accomplished your goals in the past 4 weeks?” It is used to determine the patient's perceived goal accomplishment at the end of the 4-week interdisciplinary chronic pain management programme that was the setting for our study. The SES is scored using a 5-point scale (1=poorly, 5=excellent); higher scores reflect higher goal accomplishment.

Design and Analyses

All data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 19 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Test–retest reliability

Patients completed the TSK-11 on Day 1 (admission) and Day 5. A 5-day interval was chosen to minimize the effects of recall and potential clinical change.

The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC2,1) and the standard error of measurement (SEM) were calculated from a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with patients and days as factors. We also calculated the level of confidence in the TSK-11 scores by multiplying SE and the z-value associated with the 2-tailed 90% confidence level (z=1.65) and the 90% confidence level of the minimal detectable change (MDC90) of the TSK-11 using SEM×1.65×√2.24

Validity

As there is no criterion standard for fear of movement, we applied a construct-validation process. We theorized that two different measures that assess a similar attribute should be highly correlated. We therefore assessed cross-sectional convergent construct validity25 by calculating the Pearson product–moment correlation between TSK-11 and PCS scores at admission.

Sensitivity to change

We also applied a construct-validation process to assess the ability of the TSK-11 score to detect change. We theorized that people who had attained their goals would have reduced their fear of movement or re-injury. Many of the goals set and achieved in the 4-week programme pertain to functional improvements; for example, gardening or woodworking involves some component of movement, such as bending and alternating positions. We used the SES as a reference standard to dichotomize the participants into two groups: those who scored 3, 4, or 5 on the SES at discharge were categorized as having an important reduction in their fear of movement/re-injury, while those who scored 1 or 2 were categorized as not having an important reduction in their fear of movement/re-injury.

Sensitivity to change was quantified using two methods. First, we used the results of a within- and between-patients repeated-measures ANOVA. The within-patient factor (time) was represented by admission and discharge TSK-11 scores; the between-patients factor (group) was represented by the high (3–5) and low (1, 2) discharge SES scores. The time×group interaction is an indicator of sensitivity to change.26,27 Second, we performed a receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis to determine how well the TSK-11 differentiated patients who had achieved an important reduction in their fear of movement, as assessed by the SES, from those who did not. The area under the ROC curve assesses how well a measure can discriminate between patients in two groups; areas of 1.0 and 0.5 represent perfect and chance discrimination, respectively.28

RESULTS

Participants

Demographic data for participants in the prospective and retrospective samples were not significantly different, and are therefore combined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants* |

Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | — | 43.8 (9.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 (39) | — |

| Female | 45 (61) | — |

| Work status | ||

| Employed | 19 (26) | — |

| Unemployed | 37 (50) | — |

| Missing data | 18 (24) | — |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 6 (8) | — |

| Married/common law | 38 (52) | — |

| Divorce/separated/widowed | 12 (16) | — |

| Missing data | 18 (24) | — |

| Education, y | 54 (73) | 12.8 (3.5) |

| Missing data | 20 (27) | — |

| Pain duration, mo | 53 (72) | 41.2 (28.0) |

| Missing data | 21 (28) | — |

| Time since last employment, mo | 50 (68) | 24.5 (17.0) |

| Missing data | 24 (32) | — |

Unless otherwise specified.

Test–retest reliability

A total of 18 participants completed the TSK-11 on Day 1 and Day 5; mean (SD) TSK-11 score was 30.67 (5.53) on Day 1 and 33.22 (5.80) on Day 5. The test–retest reliability (ICC2,1) was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.58–0.93); SEM was 2.41 (90% CI, 1.47–2.49); and MDC90 was 5.6 points.

Validity

Of 74 participants, 70 completed the TSK-11 and the PCS at admission. Mean (SD) TSK-11 and PCS scores at admission were 30.4 (6.6) and 32.9 (12.8). The association (Pearson product–moment correlation) between TSK-11 and PCS scores was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.43–0.73).

Sensitivity to change

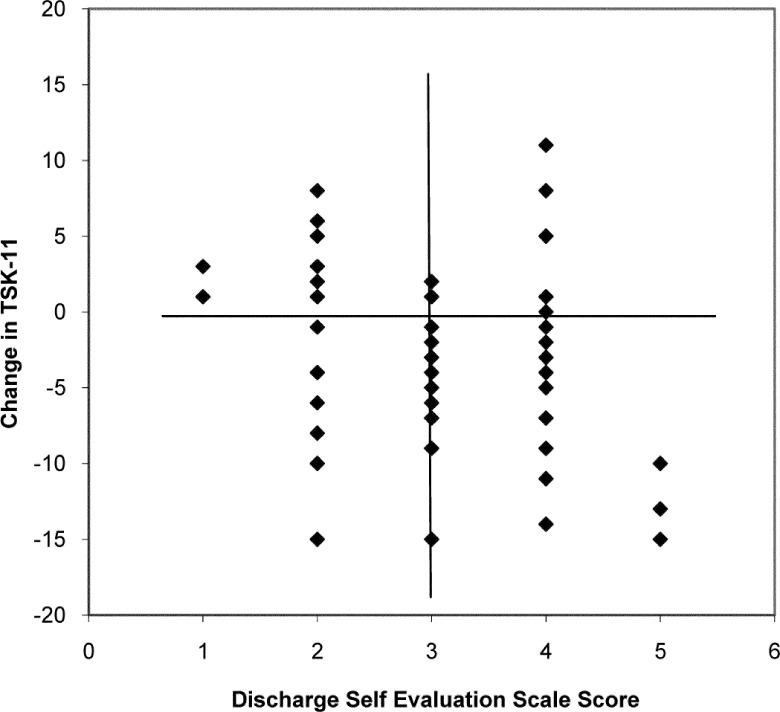

Of 74 participants, 63 completed the TSK-11 at admission and discharge and the SES at discharge. Of those 63, 30% (19 participants) evaluated their goal accomplishment as poor to fair (SES 1 or 2; see Figure 2). Their mean (SD) TSK-11 change score was −0.47 (5.8). The remaining 70% (44 participants) reported their goal accomplishment as good to excellent (SES 3, 4, or 5). Their mean (SD) TSK-11 change score was −4.18 (5.3). The group×time ANOVA interaction was statistically significant (F1,61=6.10, p=0.016); the area under the ROC curve was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.57–0.88).

Figure 2.

TSK-11 change score versus discharge Self-Evaluation Scale score (n=63 patients with complete data).

DISCUSSION

Our study builds on previous research by determining the test–retest reliability, cross-sectional convergent construct validity, and sensitivity to change of the TSK-11 in a heterogeneous English-speaking population with chronic pain.

The test–retest reliability analysis produced an ICC of 0.81 with a wide 95% CI (0.58–0.93). According to Cohen,29 a value of 0.8 is considered high. Conservatively, the test–retest reliability is no worse than 0.58, which is considered moderate.29 Our test–retest reliability results were consistent with those reported by Woby and colleagues in a sample of people with chronic LBP.21 More recently, in a group of people with shoulder pain, test–retest reliability of the TSK-11 was found to be 0.84.30 Lundberg and colleagues reported that test–retest reliability of the TSK was 0.72 in a group of people with chronic LBP.19

In our study, the SEM of the TSK-11 was 2.41 (90% CI, 1.47–2.49), similar to the findings of Woby and colleagues.21 The wide 95% CI in our study may be attributable to the small sample size.

We estimated the cross-sectional convergent construct validity of the TSK-11 through its association with the PCS; we found a moderate correlation (0.60) that compares favourably with those found in previous studies (0.32 to 0.54).31–33 The moderate correlation we observed can be explained by reviewing the definitions of the PCS and the TSK-11: while the PCS captures the patient's perspective on different thoughts and feelings experienced when encountering pain, and reflects his or her past painful experiences, the TSK-11 assesses future fear of movement or of re-injury due to movement. Thus, it is likely that the two measures are assessing different aspects of pain, which may explain why the magnitude of the correlation is not very high.

TSK-11 scores demonstrated moderately high sensitivity to change (0.73) in our study; Woby and colleagues also reported sensitivity to change of 0.73.21 In our study, the MDC90 of the TSK-11 was 5.6 points; in another study,34 the MDC95 of the TSK in patients with acute LBP was shown to be 9.2 points (95% CI, 8.4–10.3). However, it is not clear whether or not these two metrics can be compared, as the TSK-11 is a subset of the TSK-17. From the data provided by Woby and colleagues,21 we calculated the MDC90 to be 5.9 points, based on Woby's SEM of 2.54, which is similar to our SEM estimate of 2.41. The MDC90 of 5.6 points that we observed means that when stable patients are assessed on two occasions, 90% of them will display random fluctuations of <5.6 points in their score.35 Knowing the MDC allows clinicians to determine whether an observed change in the score is a true change or one associated with error/chance: if the observed change is less than the MDC value, then this change cannot be distinguished from measurement error.36 For example, if the change in a patient's TSK-11 score is <5.6, then one cannot be certain that that patient has truly changed. We were unable to locate other studies reporting the MDC90 in a heterogeneous population of chronic pain patients, and we therefore suggest that further research in this area is needed.

LIMITATIONS

The methodological aspects of our study warrant careful consideration. First, all participants were referred to the 4-week pain management programme, which may have introduced a referral bias, as people who were referred may have differed from people who were not referred. In addition, participants in our study were volunteers, and may have been different from others who did not volunteer (volunteer bias). Outcomes from 20% of participants were not included in the data analysis because of missing data. As a result of this combination of volunteer bias, referral bias, and exclusion of certain participants' scores from the data analysis, our sample may not have been truly representative of the population with chronic pain, and therefore the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Second, the sample size used for the test–retest reliability study was small. Third, because our findings are based on a sample of participants who attended a 4-week chronic pain management programme, they cannot be generalized to other chronic pain populations with different characteristics. Fourth, a chronic pain programme SES was used as the reference standard to differentiate patients who had achieved an important reduction in their fear of movement from those who had not; this scale required participants to rate their goal accomplishment at the end of the 4-week programme, but did not ask them specifically about changes in their fear of movement. The extent to which SES ratings reflect a change in pain-related fear of movement is unknown; participants' ratings of goal accomplishment may be related to their beliefs about their pain-related fear of movement or re-injury, but this hypothesis needs to be tested.

CONCLUSION

Our findings indicate that the TSK-11 has adequate reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change in evaluating pain-related fear of movement in a heterogeneous population of patients with chronic pain. This study adds to the evidence that the TSK-11 may have a broader application in a heterogeneous pain population.37

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

Fear of movement and re-injury, also known as kinesiophobia, has traditionally been measured using the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). This measure, revised to create a shorter version known as the TSK-11, was tested in a sample of patients with LBP and found to have similar psychometric properties as the original TSK.

What this study adds

Our study builds on previous research by determining the test–retest reliability, cross-sectional convergent construct validity, and sensitivity to change of the TSK-11 in a heterogeneous English-speaking population with chronic pain.

Physiotherapy Canada 2012; 64(3);235–241; doi:10.3138/ptc.2011-10

References

- 1.Williams AC, Nicholas MK, Richardson PH, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive behavioural programme for rehabilitating patients with chronic pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43(377):513–8. Medline:8312023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tota-Faucette ME, Gil KM, Williams DA, et al. Predictors of response to pain management treatment: the role of family environment and changes in cognitive processes. Clin J Pain. 1993;9(2):115–23. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199306000-00006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002508-199306000-00006. Medline:8358134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapoport J, Jacobs P, Bell NR, et al. Refining the measurement of the economic burden of chronic diseases in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2004;25(1):13–21. Medline:15298484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Den Kerkhof EG, Hopman WM, Towheed TE, et al. Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group. The impact of sampling and measurement on the prevalence of self-reported pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8(3):157–63. doi: 10.1155/2003/493047. Medline:14657983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook AJ, Brawer PA, Vowles KE. The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: validation and age analysis using structural equation modeling. Pain. 2006;121(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.018. Medline:16495008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, et al. Outline of a Fear-Avoidance Model of exaggerated pain perception—I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(4):401–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8. Medline:6626110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asmundson G, Norton P, Vlaeyen J. Fear-avoidance models of chronic pain: an overview. In: Asmundson G, Vlaeyen J, Crombez G, editors. Understanding and treating fear of pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wideman TH, Sullivan MJL. Differential predictors of the long-term levels of pain intensity, work disability, healthcare use, and medication use in a sample of workers' compensation claimants. Pain. 2011;152(2):376–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.044. Medline:21147513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan M, Bishop S, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philips HC. Avoidance behaviour and its role in sustaining chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 1987;25(4):273–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90005-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(87)90005-2. Medline:3662989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995a;62(3):363–72. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N. Medline:8657437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kori SH, Miller RP, Todd DD. Kinesiophobia: a new view of chronic pain behavior. Pain Manag. 1990;3:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burwinkle T, Robinson JP, Turk DC. Fear of movement: factor structure of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2005;6(6):384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.355. Medline:15943960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Childs JD. Psychometric properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in patients with neck pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(2):109–17. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815b61f1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815b61f1. Medline:17993982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French DJ, France CR, Vigneau F, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic pain: a psychometric assessment of the original English version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) Pain. 2007;127(1-2):42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.016. Medline:16962238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houben RM, Leeuw M, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Fear of movement/injury in the general population: factor structure and psychometric properties of an adapted version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. J Behav Med. 2005;28(5):415–24. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9011-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9011-x. Medline:16187010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roelofs J, Goubert L, Peters ML, et al. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(5):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.016. Medline:15324781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinkels-Meewisse EJ, Swinkels RA, Verbeek AL, et al. Psychometric properties of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia and the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire in acute low back pain. Man Ther. 2003;8(1):29–36. doi: 10.1054/math.2002.0484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1054/math.2002.0484. Medline:12586559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundberg M, Styf J, Carlsson SG. A psychometric evaluation of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia—from a physiotherapeutic perspective. Physiother Theory Pract. 2004;20(2):121–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09593980490453002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamé IE, Peters ML, Kessels AG, et al. Test–retest stability of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia in chronic pain over a longer period of time. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(6):820–6. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105308093866. Medline:18697895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, et al. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain. 2005;117(1-2):137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029. Medline:16055269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hapidou EG. Program evaluation of pain management programs; 9th Inter-Urban Pain Conference; 1994 Oct 10; Kitchener, ON. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hapidou EG. Coping adjustment and disability in chronic pain: admission and discharge status in a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Poster; 8th World Congress of Pain; 1998 May 26; Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, et al. A taxonomy for responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):1204–17. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00407-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00407-3. Medline:11750189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stratford PW, Riddle DL. Assessing sensitivity to change: choosing the appropriate change coefficient. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-3-23. Medline:15811176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman GR. Issues in the use of change scores in randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(11):1097–105. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90051-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(89)90051-6. Medline:2809664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egan JP. Signal detection theory and ROC analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mintken PE, Cleland JA, Whitman JM, et al. Psychometric properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in patients with shoulder pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(7):1128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.009. Medline:20599053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severeijns R, van den Hout MA, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Pain catastrophizing and general health status in a large Dutch community sample. Pain. 2002;99(1-2):367–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00219-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00219-1. Medline:12237216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JWS, Heuts PHTG, et al. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80(1-2):329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00229-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00229-2. Medline:10204746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlaeyen JWS, Kole-Snijders AMJ, Rotteveel AM, et al. The role of fear of movement/reinjury in pain disability. J Occup Rehabil. 1995b;5(4):235–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02109988. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02109988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostelo RWJG, Swinkels-Meewisse IJCM, Vlaeyen JWS, et al. Assessing pain and pain-related fear in acute low back pain: what is the smallest detectable change? Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(4):242–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03002999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03002999. Medline:18001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barreca SR, Stratford PW, Lambert CL, et al. Test–retest reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the Chedoke arm and hand activity inventory: a new measure of upper-limb function for survivors of stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.017. Medline:16084816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, et al. Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Phys Ther. 1996;76(4):359–65. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.4.359. discussion 366–8 Medline:8606899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roelofs J, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH, et al. Fear of movement and (re)injury in chronic musculoskeletal pain: evidence for an invariant two-factor model of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia across pain diagnoses and Dutch, Swedish, and Canadian samples. Pain. 2007;131(1-2):181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.008. Medline:17317011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]