Three-dimensional (3D) network polymers are an important family of materials. For many applications of 3D networks it is important to combine high modulus, high tensile strength, and high extensibility.1 Rigid network materials tend to fail after only a short extension. While flexible elastomers are more extensible, they usually have low moduli and exhibit shallow stress-response. Although many engineering approaches and chemical modifications2 have been developed to improve mechanical properties of network polymers, it remains a challenge to design ideal networks that have a combination of desired properties. Among chemical methods, interesting work has been reported on using inter-chain hydrogen bonding to improve polymer physical properties.3 Given the importance of cross-linker structure on mechanical properties of network polymers, it is surprising that there is very limited investigation on designing molecularly engineered cross-linkers to enhance network properties. Herein we introduce a novel biomimetic design of a reversibly unfolding modular cross-linker that can increase elastomer stiffness without sacrificing extensibility leading to a dramatic tensile strength enhancement.

Our biomimetic concept is based on the modular design observed in many biopolymers, such as the skeletal muscle protein titin and connective proteins in both soft and hard tissues, that have a remarkable combination of strength and elasticity.4 Single-molecule nanomechanical studies have revealed that their combined mechanical properties originate from their unique modular structure, which sequentially unfolds upon deformation providing the molecular mechanism to sustain high force (strength) and to yield high elongation (elasticity).5 Inspired by nature, our group has been mimicking this modular domain strategy in the pursuit of synthetic polymers with advanced mechanical properties. A number of biomimetic modules have been successfully designed and incorporated into linear polymers.6,7 Single-molecule and bulk properties validated our biomimetic concept of using modular structures to enhance polymer properties. This communication describes the first example of introducing a reversibly unfolding modular cross-linker into 3D networks to enhance their mechanical properties.

Our concept is illustrated in Figure 1. A stress applied from any direction to a 3D network will be ultimately transferred across the individual network junctions, where biomimetic modules can be reversibly unfolded. Since it requires significant forces to unfold the modules held by strong multiple hydrogen bonds, further extension can be gained without sacrificing the modulus. In addition, we propose that the enhanced energy dissipation capability by unfolding the biomimetic modules should lead to significant increases in both extensibility and tensile strength. In this study we use a simple poly(n-butyl acrylate) network to demonstrate this concept.

Figure 1.

Concept of biomimetic design of biomimetic modular cross-linker for enhancing network mechanical properties.

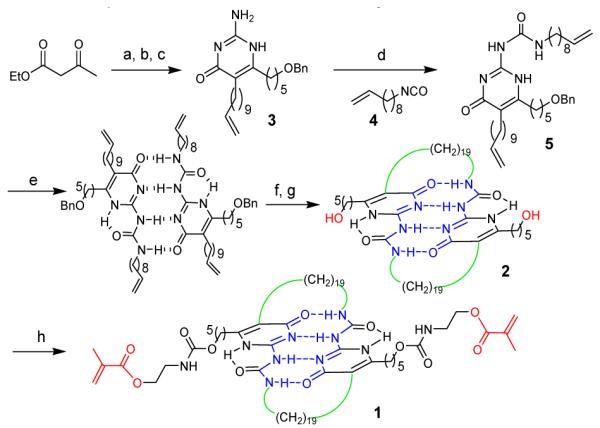

The biomimetic cross-linker is based on the quadruple hydrogen bonding 4-ureido-2-pyrimidone (UPy) motif originally developed by the Meijer and coworkers.8 The synthesis of the module is shown in Scheme 1 (also see synthetic details in Support Information). Double alkylation of ethyl acetoacetate followed by guanidine condensation afforded the alkenyl-pyrimidone interme-diate 3. The isocyanate 4 was coupled to the pyrimidone 3 to yield 5. Upon dimerization in DCM, ring-closing metathesis (RCM) effectively cyclize the two UPy units.9 Despite the possibility of other isomer formation, only the desired product was obtained (see Supporting Information). A one-pot reduction and deprotection through hydrogenation gave the diol module 2. Finally, capping 2 with 2-isocyanatoethyl methacrylate at both ends provided the UPy sacrificial cross-linker, 1, which was characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, FTIR, and MALDI-TOF MS (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the biomimetic UPy modular cross-linker.

a) NaH, n-BuLi, THF, Br(CH2)4OBn, 52%; b) Br(CH2)9CH=CH2, K2CO3 , DMF, rt, 12h, 47%; c) Guanidine carbonate, EtOH, reflux, 12h, 72%; d) 4, Py, reflux, 6 h, 83%; e) DCM. f) (Cy3P)2RuCl2=CHPh, DCM, reflux, 1-2h, 65%; g) Pd(OH), 1 atm H2, THF, 68%; h) CHCl3, 2-isocyanatoethyl methacrylate, DBTDL.

In this model study, we chose poly(n-butyl acrylate) as the backbone because this polymer exhibits elastomeric properties upon cross-linking (Tg of −54 °C) 10 and can be easily synthesized by free radical polymerization. A series of transparent rubbery films were prepared by copolymerization of n-butyl acrylate with the cross-linker 1 using AIBN as initiator. A poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) dimethacrylate (Mn = 750) was used as the control cross-linker. This cross-linker is very soluble and flexible, and when fully stretched, it has approximately the same length as the fully unfolded UPy cross-linker 1. The thermosets were characterized by FTIR, DSC, and static stress-strain and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA). The Tg’s measured by DMA for controls and real samples are all below room temperature (see Fig. S8 in Support Information).

Table 1 summarizes the mechanical parameters obtained from the stress-strain studies and Fig. 2 compares the stress-strain curves for the sample and control specimen having 6 mol% cross-linkers. Compared to the control, the key mechanical properties are significantly improved by introducing our biomimetic cross-linker. While the improvement is modest for the 2% samples, in the 4% UPy case, both modulus and tensile strength increase substantially without sacrificing the maximum elongation. At 6% incorporation, the UPy sample maintains a continuously improved modulus and a greater than 700% increase in tensile strength while maintaining a similar level of elongation. The rubbery plateau moduli obtained from DMA measurements (see Fig. S6 in Supporting Information) agree well with the static tensile data.

Table 1.

Stress-strain data for both sample and control systems.

| Sample | Young’s Modulus (E) (MPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Elongation at Failure (mm/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG (2%) | 1.24 (± .07) | 0.52 (± .04) | 0.59 (± .06) |

| PEG (4%) | 1.67 (± .12) | 0.57 (± .06) | 0.45 (± .05) |

| PEG (6%) | 3.82 (± .13) | 0.63 (± .17) | 0.19 (± .05) |

| UPy (2%) | 1.67 (± .09) | 0.95 (± .12) | 0.75 (± .07) |

| UPy (4%) | 3.89 (± .02) | 2.47 (± .38) | 0.69 (± .05) |

| UPy (6%) | 5.57 (± .08) | 4.5* | 0.8* |

The data for specimens that did not break within the 10N load limit are marked with an asterisk (strain rate: 100 mm/min, at room temperature).

Figure 2.

Stress-strain curves for 6% crosslinked poly(n-butyl acrylate) rubber for the sample (blue) and control specimen (strain rate: 100 mm/min, at room temperature).

The comparison between the UPy samples and the PEG controls validates our biomimetic concept. For the PEG controls, the increase of modulus at higher cross-linker levels trades off with the maximum elongation. This is typical for regular thermoset elastomers: higher cross-linking density results in more rigid and less elastic rubbers.2,11 In contrast, in our UPy samples we observed a consistent increase in modulus and tensile strength without sacrificing the extensibility. We attribute this to the increased energy dissipation ability of our modular cross-linker.12 While the modulus is increased at higher cross-linking density, the reversibly unfolding modules can act as energy dissipating units to prevent fracture formation. To extend the control polymer (an entropic elastomer) by 100%, the free energy change (ΔG) is roughly −TΔS, which is estimated to be ~0.6 kcal/mol.13 In contrast, it takes ~11 kcal/mol to fully unfold the UPy folded module (based on Kd of ~10−8 M−1 in toluene).8 The enhancement of energy dissipation by the modular cross-linker is supported by the much larger loss moduli measured by DMA for the real samples as compared to the controls (see Fig. S7). Whereas potential nano- and micro-phases may also contribute to the bulk mechanical properties, on the basis of the optical transparency of the samples and our small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) data (Fig. S9 & 10), it is unlikely to have nano- or micro-phases existing in our system.

In summary, we describe here the biomimetic design of a reversibly unfolding modular cross-linker to enhance mechanical properties of 3D networks. A UPy-based cyclic modular cross-linker was synthesized via multi-step organic synthesis. Stress-strain measurements show that the poly(n-butyl acrylate) samples containing the modular cross-linker exhibit significantly enhanced mechanical properties over the control samples. Most interestingly, at higher cross-linking density both modulus and tensile strength are significantly improved without sacrificing the extensibility. This introduces a novel biomimetic concept to enhance rubber properties through design of molecularly engineered cross-linkers. Further studies are currently ongoing to extend this concept to other network systems and to probe the mechanisms for the property enhancement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowldgement

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Institute of Health (R01EB004936) and Department of Energy (DE-FG02-04ER46162). We thank Professor Andrew Putnam for the MTS instrument and Professor Albert F. Yee for the DMA instrument. Z.G. acknowledges a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award and a Humboldt Bessel Research Award.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthesis and characterization of cross-linker and polymers, MALDI-TOF MS, MTS stress-strain experiments. This material is available free of charge at http//:pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Allcock HR, Lampe FW, Mark JE. Contemporary Polymer Chemistry. 3 ed Pearson Education, Inc.; New Jersey: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mark JE, Erman B, Eirlich FR. Science and Technology of Rubber. 2 ed Academic Press; San Diego: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Muller M, Seidel U, Stadler R. Polymer. 1995;36:3143–3150. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamauchi K, Lizotte JR, Long TE. Macromolecules. 2003;36:1083–1088. [Google Scholar]; (c) Park T, Zimmerman SC, Nakashima S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6520–6521. doi: 10.1021/ja050996j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Law RC, Carl P, Harper S, Dalhaimer P, Speicher DW, Discher DE. Biophys. J. 2003;84:533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74872-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. Science. 1997;276:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C. Science. 1997;276:1112–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Li H, Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Fowler SB, Clarke J, Fernandez JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:6527–6531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120048697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Smith BL, Schaffer TE, Viani M, Thompson JB, Frederick NA, Kindt J, Belcher A, Stucky GD, Morse DE, Hansma PK. Nature. 1999;399:761–763. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Guan Z, Roland JT, Bai JZ, Ma SX, McIntire TM, Nguyen M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2059–2065. doi: 10.1021/ja039127p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Roland JT, Guan Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14328–14329. doi: 10.1021/ja0448871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sijbesma RP, Beijer FH, Brunsveld L, Folmer BJB, Hirschberg JHKK, Lange RFM, Lowe JKL, Meijer EW. Science. 1997;278:1601–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mohr B, Weck M, Sauvage J-P, Grubbs RH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1997;36:1308–1310. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bandrup J, Immergut EH. Polymer Handbook. 4th ed ohn Wiley & Sons; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Treloar LRG. The Physics of Rubber Elasticity. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- (12).It should be noted that direct contribution of distance gain upon unfolding of UPy cross-linker to the overall extension is relatively small. For example, in a totally unrealistic model of a straight chain containing 94 n-butyl acrylate monomer units and 6 UPy modules linked in series (6 mol%), complete unfolding of all 6 modules will result in less than 20% gain in extension.

- (13).Hiemenz PC. In: Polymer Chemistry: The Basic Concepts. 1 ed Dekker M, editor. New York: 1984. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.