Abstract

Objectives

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) developed two measures of potentially inappropriate prescribing: exposure to high-risk medications in the elderly (HRME) and drug-disease interactions (Rx-DIS). Both HRME and Rx-DIS exposures are prevalent in Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities, but the extent to which they vary by facility is unknown. We describe facility-level variation in these quality measures and identify facility characteristics associated with high-quality prescribing.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

VA Healthcare System.

Participants

Veterans ≥ 65 years of age with at least one inpatient or outpatient visit in 2005-2006 (n=2,023,477; HRME exposure) and a sub-sample with a history of falls or hip fractures, dementia, or chronic renal failure (n=305,059; Rx-DIS exposure).

Measurements

Incident use of any high-risk medication (iHRME) and incident drug-disease interactions (iRx-DIS); facility-level rates and facility-level predictors of iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure, adjusting for differences in patient characteristics.

Results

Overall, 94,692(4.7%) Veterans had iHRME exposure. At the facility-level, iHRME exposure ranged from 1.56% at the lowest facility to 12.76% at the highest (median 4.73%). In the sub-sample, 9,803(3.2%) Veterans had iRx-DIS exposure, with a facility-level range from 1.30% to 5.85% (median 3.21%). In adjusted analyses, patients seen in facilities with formal geriatric education had lower odds of iHRME (OR=0.86, 95%CI=0.77-0.96) and iRx-DIS (OR=0.95, 95%CI=0.88-1.01). Patients seen in facilities caring for fewer older patients had greater odds of iHRME (OR=1.54, 95%CI=1.35-1.75) and iRx-DIS exposure (OR=1.22, 95%CI=1.11-1.33).

Conclusion

Substantial variation in the quality of prescribing for older adults exists across VA facilities, even after adjusting for patient characteristics. Our findings support the idea that higher quality prescribing is found in facilities caring for a larger number of older patients and facilities with formal geriatric education.

Keywords: Potentially inappropriate prescribing, HEDIS measures, quality of care, pharmacoepidemiology

INTRODUCTION

The appropriate use of prescription drugs is a key component of high-quality care in older adults. Careful prescribing is particularly important in the elderly, due to multiple comorbidities, greater likelihood for polypharmacy, and altered pharmacokinetics/pharmamcodynamics of drugs.1-3 Prior studies have found that potentially inappropriate medication use among older adults is common and is linked to poor patient outcomes, including adverse drug events, falls, hospitalizations, increased length of hospital stay, as well as increased healthcare costs and even mortality.4-14

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) incorporated two measures of potentially inappropriate prescribing into its HEDIS (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) quality scores: 1) use of drugs to avoid in the elderly (high-risk medications in the elderly, or HRME), and 2) presence of a potentially harmful drug-disease interaction in the elderly (Rx-DIS). The NCQA measure of drug-disease interactions was based on earlier measures by Lindblad and colleagues,15 for which an expert panel reached agreement about a subset that could be measured using administrative data (e.g., use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS) in those with chronic renal failure). Despite some controversy about the clinical relevance of measures of potentially inappropriate drug use in individual patients,16 the inclusion of these measures into HEDIS scores means that they are now intertwined with provider, health plan, and facility reimbursements, thus taking on additional importance.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system is a unique setting to study potentially inappropriate prescribing because of the uniform drug benefit across the system, and because of the centralized pharmacy benefits management (PBM) services and utilization management. Prior research identified significant variation in exposure to Beers criteria medications (i.e., the broader group of drugs on which the HRME measure was based) in VA patients in FY 2000.17 Prior studies have also documented a significant level of both HRME and Rx-DIS exposure in the VA.18, 19 No prior studies, however, have examined the extent to which prescribing based on the updated HEDIS measures varies by facility across the VA.

Quantifying the variation in inappropriate prescribing across VA facilities is important because it can help target prescribing improvement initiatives to those facilities needing them most. Programs that aim to decrease inappropriate prescribing may have a large effect at facilities that have high rates of use, and little effect at facilities that have low baseline rates of inappropriate prescribing. Studying facility-level variation can also identify ‘high-performing’ facilities that can serve as models for best practices. Our study may also serve as a model for how to study variation in the quality of prescribing across facilities in other health systems outside the VA.

Accordingly, we examined national prescribing data for over two million Veterans ≥65 years of age in 2006 to: 1) describe facility-level variation across the VA in the use of HEDIS potentially inappropriate medications, and 2) identify facility-level predictors of potentially inappropriate medication exposure while controlling for individual patient characteristics.

METHODS

Setting, Data Sources, and Study Sample

The VA is the one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States (U.S.), with over 8 million Veterans enrolled and more than 5 million receiving care.20, 21 We obtained national inpatient and outpatient administrative data (for demographic information, hospitalization and clinic visits, and diagnostic codes) and PBM pharmacy data from fiscal years (FY) 2005-2006 for all Veterans who were 65 or older at the beginning of FY06. To ensure that we could identify comorbid conditions and prior medication use, we limited our sample to those who had at least one inpatient or outpatient visit in both FY05 and 06.

This large cohort of older Veterans formed the study sample for the analysis of HRME (n=2,023,477). We identified a sub-sample (n=305,059) of these individuals having ICD-9 codes in FY05 indicative of falls or hip fractures, dementia, or chronic renal failure, which are the three disease conditions specified by NCQA in which Rx-DIS exposures are examined.

Study Outcome

Our two primary outcomes were the presence (in 2006) of a new (incident) prescription for any high-risk medication among the cohort (iHRME) and the presence of new (incident) prescription leading to a drug-disease interaction among the sub-sample with falls or hip fractures, dementia, or chronic renal failure (iRx-DIS). We focused on ‘incident’ HRME and Rx-DIS rather than ‘prevalent use’ – that is, we identified Veterans who had a new prescription for a drug included in the HEDIS HRME and Rx-DIS definitions.22 New prescriptions were identified based on the absence of any prescription of the same medication in the previous fiscal year (FY05). Although the NCQA defines these HEDIS measures as prevalent HRME and Rx-DIS, we focused on incident use because it more accurately reflects the actual prescribing habits at the time of the study (compared to prescriptions that may be inappropriate but the patient has been on for several years). Aside from the focus on incident prescribing, the iHRME and iRx-DIS measures are defined according to NCQA guidelines,22 and are similar to prior analyses.18, 19 We calculated the overall proportion of older adults with any iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure and the proportion of older adults at each VA facility with the two outcomes.

Facility Characteristics

We assigned individuals to the one VA facility where the majority of care was received in FY05. Each VA facility was coded as rural or urban based on facility zip code using rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes from the US Department of Agriculture.23, 24 Teaching status was determined based on the presence of either medical school affiliation or residency training program from the American Hospital Association Database.25 We also determined whether the VA facility had a formal geriatric education program, based on the presence of either a VA Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) or an affiliated civilian Geriatric Education Center. Since a prior study suggested that individuals seen in facilities with high rates of geriatric care were less likely to receive inappropriate medications even if they did not receive geriatric care themselves,17 we also calculated geriatric care saturation as the proportion of patients at each facility 65 years and older who received geriatric care in FY05 (defined as a visit to a geriatric outpatient clinic or receipt of care in an inpatient geriatric evaluation and management unit, defined based on geriatric clinic stop codes and inpatient bedsection). Finally, we also hypothesized that there may be an indirect benefit for patients being cared for at facilities that treat a larger number of older patients; we thus created a variable for “geriatricness,” which is the proportion of the facility patient population that is 65 or older.

Patient Demographics, Health Status, and Access to Care

We included a number of demographic, health status, and access variables in our analyses to adjust for differences in these characteristics across VA facilities.26 These variables have been previously studied in relation to both HRME and Rx-DIS exposures.18, 19, 27 Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, and gender, as obtained from VA administrative data sources. We categorized race/ethnicity into 4 categories (white, black, Hispanic, other), including a category for missing or unknown race, which was present for 22% of the sample, as is consistent with VA administrative sources during the study timeframe.28

We derived a number of health status variables from the prior year (FY05). We used ICD-9 codes from the inpatient and outpatient files to identify chronic conditions included in the Selim Physical and Mental Comorbidity Indices (CI).29, 30 The Physical CI includes 30 chronic conditions (e.g., cerebrovascular disease, diabetes) that are counted to create a score ranging from 0-30, and the mental CI includes six comorbid psychiatric conditions (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, and schizophrenia) that are also summed. Because the mental CI was highly skewed, we dichotomized the variable (0 vs. ≥1) to indicate the presence of a mental comorbidity. These measures have been found to be associated with mortality and also suboptimal prescribing in prior work.31-33 We also included a count of unique medication classes taken and included variables for the presence of a hospitalization or emergency room (ER) visit in the prior year.

We derived two variables measuring individuals’ access to medications. The first was an indicator for whether or not pharmacy copayments were required, based on VA priority groups associated with health status and illness severity as well a socioeconomic status. For our purposes, Veterans with a service-connected disability ≥ 50% or those with catastrophic disability, very low income, or specific service connected experiences, were defined as having no copayments (copayments otherwise were $8 in 2006). Because prior work indicated that receipt of geriatric care was associated with lower likelihood of receiving a potentially inappropriate medication, we identified those who received prior geriatric care (i.e., geriatric outpatient clinic or inpatient geriatric evaluation and management unit) in FY 05.17, 34

Analysis

We summarized all variables using descriptive statistics. We then described the proportion of Veterans at each VA facility with iHRME exposure among the full cohort, and the proportion of Veterans with iRx-DIS exposure among the sub-sample with specific chronic conditions. We compared those with and without iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure using chi-square and t tests, as appropriate. We used two separate multivariable regression models to examine adjusted rates of iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure. The first was a multivariable logistic regression model with fixed effects for each VA facility; from this model, we obtained the facility mean probability of iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure, adjusting for patient covariates, using the ‘lsmeans’ statement (GLIMMIX with ILINK option) in SAS.35, 36 Our second multivariable analysis used random intercept logistic regression to examine facility predictors of iHRME and iRX-DIS exposure, controlling for individual patient characteristics and using VA facility as a random effect. In the final models, we excluded the Selim Physical comorbidity variable because of its strong correlation with number of prescription medications, which resulted in collinearity. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The final cohort included 2,023,477 Veterans age 65 or older who received care at one of 128 VA facilities in FY05 and 06. Of this cohort, 305,059 had a diagnosis of falls/hip fracture, dementia, or chronic renal failure and were thus included in the analysis of iRx-DIS exposure. Of the 128 VA facilities, most were urban (82%), 61 (48%) were classified as teaching facilities and 40 (31%) had a geriatric education program. Most facilities had a very small proportion of their patients receiving geriatric care (geriatric care saturation), with only the top quartile of facilities having more than 3% of patients in geriatric care. The ‘geriatricness’ of the facilities ranged from less than 45% of patients being over age 65 in the lowest quartile of facilities, to over 56% in the top quartile (data not shown).

High-risk Medication Use in the Elderly (iHRME)

Overall, 94,692 (4.7%) Veterans had a new iHRME prescription in FY06 (Table 1). Veterans with iHRME were more likely than those without iHRME exposure to be exempt from copays (75.6% vs. 59.7%, p<0.001), and were more likely to have had an ER visit and hospitalization in the previous year (p<0.001). Although statistically significant, there was no clinically relevant difference in the likelihood of receiving geriatric care in the prior year between those who had and did not have iHRME exposure (2.5% vs. 2.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Older Veterans With and Without Incident HRME and Rx-DIS Exposures in Fiscal Year 2006.*

| With iHRME (n= 94,692) |

Without iHRME (n= 1,928,785) |

P Value |

With iRx-DIS (n= 9,803) |

Without iRx-DIS (n= 295,256) |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (± SD) | 74.8 (6.3) | 75.7 (6.3) | <0.001 | 78.1 (6.1) | 78.1 (6.1) | 0.22 |

| 65-74 | 51.4 | 45.8 | 30.4 | 29.9 | ||

| 75-84 | 41.4 | 45.6 | 54.5 | 54.9 | ||

| 85+ | 7.3 | 8.7 | 15.1 | 15.2 | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 97.3 | 98.3 | 97.8 | 98.1 | ||

| Race | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 71.2 | 66.4 | 69.3 | 68.7 | ||

| Black | 9.4 | 6.4 | 12.3 | 10.7 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.3 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 4.5 | ||

| Other | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Missing/Unknown | 12.6 | 22.8 | 9.7 | 14.8 | ||

| Copay Exempt | 75.6 | 59.7 | <0.001 | 80.1 | 72.0 | <0.001 |

| Selim Physical Comorbidity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0-1 | 17.6 | 27.6 | 13.7 | 16.3 | ||

| 2-3 | 42.2 | 47.2 | 35.6 | 40.5 | ||

| 4-5 | 26.9 | 19.2 | 30.1 | 27.6 | ||

| 6+ | 13.3 | 6.0 | 20.7 | 15.6 | ||

| Selim Mental Comorbidity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 78.4 | 86.4 | 67.3 | 77.4 | ||

| 1+ | 21.6 | 13.6 | 32.7 | 22.6 | ||

| Visit to an ER in previous year |

31.1 | 14.6 | <0.001 | 41.1 | 28.5 | <0.001 |

| Inpatient Hospitalization in previous year |

12.9 | 5.7 | <0.001 | 21.8 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

| # of Medications in year prior, mean (± SD) |

9.2 (5.4) | 6.6 (4.6) | <0.001 | 10.7 (5.6) | 9.4 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| 0-5 | 26.5 | 46.4 | 16.9 | 24.1 | ||

| 6-8 | 24.2 | 25.7 | 22.7 | 25.1 | ||

| 9-11 | 20.4 | 14.7 | 21.6 | 21.1 | ||

| 12+ | 29.0 | 13.1 | 38.8 | 29.7 | ||

| Received Geriatric Care | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.002 | 8.4 | 6.5 | <0.001 |

All values are column percentages unless otherwise noted.

iHRME = incident High Risk Medications in the Elderly

iRx-DIS = incident Drug-Disease Interactions

At the facility-level, the presence of iHRME exposure ranged from 1.56% of older patients at the lowest facility to 12.76% at the highest (median of 4.73, IQR 3.73-5.81). That is, at one facility about one in eight older Veterans had a prescription for a high-risk drug, compared to less than one in 60 at another facility. After adjustment for differences in patient characteristics across facilities, substantial variation in the presence of iHRME remained; Table 2 lists the VA facilities with the five highest and five lowest percentages of patients with iHRME after adjusting iHRME for all patient-level variables, along with the specific type of iHRME exposure most common at each facility. The facilities with the highest use included two in the same regional network, or VISN (Veterans Integrated Service Network, as indicated by the letters in column 2). The VA facilities with the lowest proportion of patients with iHRME also included two facilities in the same VISN. Opioids and antihistamines were the most common medication class exposures in both the highest five and lowest five facilities.

Table 2.

Highest 5 and Lowest 5 VA Facilities with Adjusted Exposure to Incident Prescriptions for High-Risk Medications in the Elderly (iHRME). The percentages indicate the proportion of individuals at a given facility with an iHRME exposure.

| Rank | VISN* | iHrme (%) | Adjusted iHRME (%)† |

95% CI | Top Drug Class Prescribed in iHRME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 12.76 | 8.41 | 7.72-9.15 | Opioids |

| 2 | B | 9.64 | 7.07 | 6.59-7.58 | Antihistamines |

| 3 | C | 8.56 | 6.96 | 6.54-7.40 | Antihistamines |

| 4 | D | 8.16 | 6.93 | 6.57-7.29 | Opioids |

| 5 | D | 7.92 | 6.54 | 6.21-6.90 | Opioids |

| 124 | E | 2.09 | 2.35 | 2.16-2.57 | Antihistamines |

| 125 | F | 2.11 | 2.32 | 2.02-2.65 | Skeletal Muscle Relaxants |

| 126 | G | 1.76 | 2.17 | 1.85-2.55 | Antihistamines |

| 127 | H | 2.09 | 2.16 | 1.95-2.39 | Antihistamines |

| 128 | E | 1.56 | 2.01 | 1.73-2.32 | Opioids |

To maintain confidentiality, each VISN is represented by a letter. Where the letters are the same, it indicates that the two VA facilities are located in the same VISN. VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

Adjusted for all patient-level variables

Drug-disease Interactions (iRx-DIS)

Overall, 9,803 (3.2%) Veterans with falls/hip fracture, dementia, or chronic renal failure had an iRx-DIS exposure (Table 1). Veterans with iRx-DIS exposure were more likely to be exempt from copays and were more likely to have ER visits and hospitalizations in the previous year (all p<0.001). Patients with iRx-DIS exposure were also more likely to have received geriatric care in the previous year (8.4% vs. 6.5%, p <0.001).

At the facility-level, the presence of iRx-DIS exposure ranged from 1.30% of older patients at the lowest facility to 5.85% at the highest (median 3.21%, IQR 2.77 – 3.58). After adjustment for differences in patient characteristics across facilities, substantial variation in the presence of iRx-DIS remained (Table 3). There was no overlap between VISNs for the highest five facilities for iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure, although three of the VISNs in the lowest five for iRx-DIS exposure were also in the lowest five for iHRME exposure (indicated by the letters E and G in the VISN column). Patients with dementia exposed to anticholinergics were the predominant group with drug-disease interactions in most of the facilities, except for the facility with the highest adjusted iRx-DIS, where use of NSAIDs among patients with chronic renal failure was the most common exposure.

Table 3.

Highest 5 and Lowest 5 VA Facilities with Adjusted Exposure to a Drug-Disease Interaction (iRx-DIS). The percentages indicate the proportion of individuals at a given facility with iRx-DIS exposure.

| Rank | VISN* | iRx-DIS (%) |

Adjusted iRx-DIS (%)† |

95% CI | Top Condition-Drug Class Leading to iRx-DIS†† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | 4.86 | 4.61 | 3.88-5.46 | Chronic Renal Failure - NSAIDs |

| 2 | J | 4.47 | 4.55 | 3.76-5.50 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 3 | K | 4.41 | 4.42 | 2.52-7.64 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 4 | L | 4.48 | 4.26 | 3.18-5.68 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 5 | J | 3.76 | 4.26 | 3.20-5.66 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 124 | E | 1.97 | 2.01 | 1.57-2.58 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 125 | M | 1.78 | 1.91 | 1.30-2.81 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 126 | E | 1.71 | 1.91 | 1.45-2.52 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 127 | A | 2 | 1.87 | 1.28-2.72 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

| 128 | G | 1.3 | 1.29 | 0.70-2.39 | Dementia - Anticholinergics |

To maintain confidentiality, each VISN is represented by a letter. Where the letters are the same, it indicates that the two VA facilities are located in the same VISN. VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

Adjusted for all patient-level variables

Of patients with dementia with a drug-disease interaction, oxybutynin, a genitourinary antispasmodic, was the most commonly used anticholinergic medication. Contraindicated classes/medications for those with dementia include those that are highly anticholinergic (e.g., 1st generation antihistamines, skeletal muscle relaxants, antispasmodics), as well as tricyclic antidepressants.

There was a moderate positive correlation (r=0.47, p<.001) between facility-level iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure, such that facilities with a greater proportion of patients with iHRME were also more likely to have iRx-DIS exposure (data not shown).

Facility-level factors associated with iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure

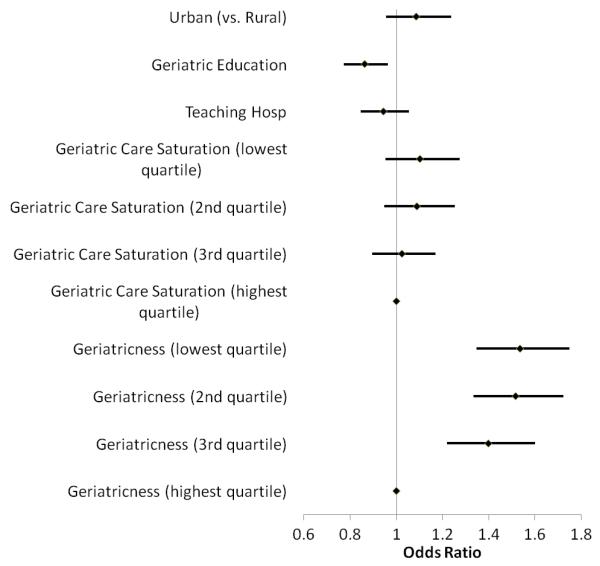

Patients seen in facilities with formal geriatric education had 14% lower odds of iHRME exposure, after adjustment for all other variables including individual receipt of geriatric care (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.86, 95% CI 0.77-0.96) (Figure 1). The proportion of patients receiving geriatric care (geriatric care saturation) was not significantly associated with iHRME (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.95-1.28 for patients seen in facilities in the lowest quartile of geriatric care saturation compared to facilities in the highest quartile). The ‘geriatricness’ of the facility, however, did have a significant association, such that patients seen in facilities with a smaller proportion of patients ≥65 years of age had greater odds of iHRME exposure (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.35-1.75 for those in lowest quartile compared to those in highest quartile).

Figure 1.

Facility Characteristics Associated with Incident HRME (High Risk Medications in the Elderly) Exposure. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from the random effects logistic regression models are plotted.*

*Adjusted for patient-level age, gender, race/ethnicity, presence of mental comorbidity, copayment eligibility, history of emergency room visits and hospitalizations in the prior year, number of medications in the prior year, and receipt of geriatric care.

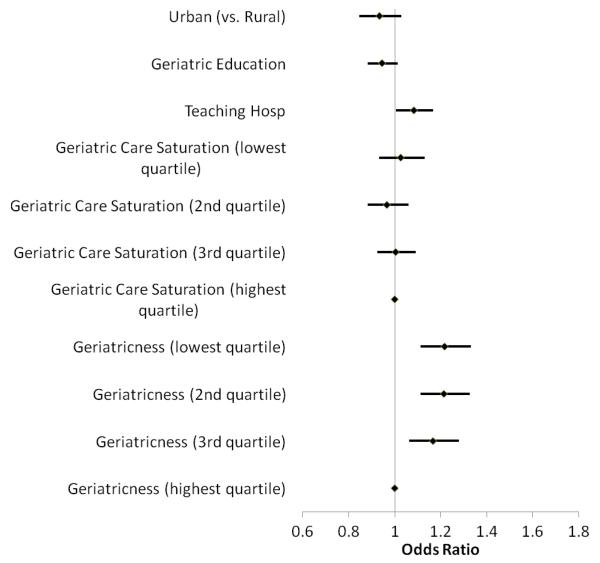

Patients seen in facilities with formal geriatric education had a 5% lower (but not statistically significant) odds of iRx-DIS exposure (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88-1.01) (Figure 2). Patient seen in teaching facilities had higher odds of iRx-DIS exposure (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01-1.17). As with iHRME, facility ‘geriatricness’ was associated with iRx-DIS exposure; patients seen in facilities with a smaller proportion of patients ≥ 65 years of age had greater odds of exposure (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.11-1.33 for those in lowest quartile compared to those in highest quartile).

Figure 2.

Facility Characteristics Associated with Incident Rx-DIS (Drug-Disease Interactions) Exposure. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from the random effects logistic regression models are plotted.*

*Adjusted for patient-level age, gender, race/ethnicity, presence of mental comorbidity, copayment eligibility, history of emergency room visits and hospitalizations in the prior year, number of medications in the prior year, and receipt of geriatric care.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to describe variation in the quality of prescribing across VA facilities as defined by HEDIS high-risk medication use and drug-disease interactions. The substantial variation reported in this study remained even after adjusting for differences in patient demographics, health status, and access measures across facilities. In addition, we detected important facility-level factors associated with the quality of prescribing to older adults in the VA, as well as evidence for regional clustering of ‘high-performing’ facilities.

We are aware of only one prior study that has examined regional differences in the quality of prescribing based on HEDIS measures, which used unadjusted data from Medicare Part D to describe variation in prevalent exposure across hospital referral regions.37 The ability to identify facility-specific rates of potentially inappropriate prescribing has additional practical significance and relevance, since national average rates, and even smaller regional rates, of inappropriate prescribing cannot identify those facilities that would benefit most from an intervention. Simply put, and as others have described in reference to clinical trials,38 any policy or intervention that is based on an average result and not targeted to those facilities most at risk may not have the intended effect. In addition, our focus on incident prescribing is important because it means that prescribers are not only simply continuing patients on medications they may have been taking for years, but they are making active clinical decisions to begin therapy with mediations that may have more risk than benefit – and these decisions are being made more frequently at some facilities than others.

In our current analysis, we found two facility characteristics associated with lower odds of both iHRME and iRx-DIS exposure. First, patients seen in facilities that had formal geriatric education programs had 14% lower adjusted odds of iHRME exposure and a 5% lower odds (although not statistically significant) of iRx-DIS exposure. Second, patients seen in facilities that care for a higher percentage of patients over age 65 (“geriatricness”) had significantly lower odds of both outcomes. It is plausible that facilities that have geriatric education programs and that treat a larger number of older patients could in some way have an institutional culture that promotes less inappropriate prescribing to older patients, over and above simply whether or not individual patients receive geriatric care. For example, there may be opinion leaders, specialty trained pharmacists or geriatricians that influence prescribing in those facilities. There may also be a volume effect, similar to the volume effect with cardiac surgery,39, 40 such that facilities taking care of more older patients may pay more attention to geriatric specific issues, whether inappropriate prescribing, falls reduction, or home-based care.

Another facility-level variable, the proportion of patients receiving geriatric care, did not have a statistically significant association with potentially inappropriate prescribing. In prior analyses using older data, there was a nearly significant 14% greater odds of prevalent HRME in patients seen in facilities with low geriatric care saturation compared to high penetration.17 We are not able to reach the same conclusion using the current data. Previous analyses examined prevalent exposure using the Beers criteria (a broader measure of inappropriate prescribing) and did not adjust for potentially important confounding characteristics such as geriatricness and geriatric education. There may also be heterogeneity in the kinds of geriatric clinics that are in place at facilities (e.g., separate clinic vs. embedded within primary care) that could weaken its overall effect on prescribing quality. It is interesting to note, however, that in a large randomized trial of outpatient geriatric care in the VA, there were no differences in inappropriate prescribing between intervention and control groups.34

Whatever the reason for high or low levels of inappropriate prescribing, facilities that fall at one end of the spectrum or the other deserve special attention. Facilities with low levels of inappropriate prescribing can serve as examples of best-practice in high-quality prescribing to older patients, and facilities with high levels of inappropriate prescribing may require additional resources to improve care. Importantly, specific aspects of geriatric care and geriatric programs that are shown to be effective and feasible deserve further study. The clustering of ‘high performing’ facilities in geographic regions (as evidenced by the clustering within VISN in Tables 3 and 4) and the correlation between iHRME and iRx-DIS exposures among facilities suggests that there may be additional important facility and regional factors to examine that are associated with the quality of prescribing.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, we were only able to capture medications and other healthcare utilization that was received within the VA. It is possible that medications were obtained outside the VA, although our data from FY 06 (October 2005-September 2006) reflect utilization prior to when many seniors were fully enrolled in the new Medicare Part D benefit (enrollment proceeded through May 2006). It is also possible that co-management of Veterans by non-VA providers affects prescribing within the VA, but we were not able to control for co-management in our analysis. In addition, our analysis of iRx-DIS relied on the diagnosis of certain chronic conditions using VA administrative data, and thus it is possible that we missed a small number of individuals who would be at risk for iRx-DIS. Second, the HEDIS potentially inappropriate prescribing measures were formally introduced in 2006, and thus our study assesses exposure prior to their formal introduction. Nonetheless, the Beers criteria and other measures of Rx-DIS on which these measures were based have been available since 1991.41-43 Third, although we attempted to include relevant comorbidities and facility factors in our analysis, there may be important unmeasured patient differences among facilities that could explain some of our findings. It may be appropriate, for example, for some patients to receive medications included on the HEDIS drugs to avoid lists if benefits outweigh risks (e.g., use of promethazine, a highly anticholinergic antiemetic for nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients), but we are not able to capture these individual circumstances using administrative records. Finally, because our data are from 2006, it may not reflect current practice; however, there is no reason to suspect that the relationship between facility-factors and potentially inappropriate prescribing has changed over the last 5 years, and our data are well-positioned to address this important question.

CONCLUSION

We examined over 2 million older patients and found substantial variation across VA facilities in potentially inappropriate prescribing. We believe our findings should lead researchers and policymakers to seek out the characteristics of those facilities that have both the best and the worse performance on these HEDIS measures, in order to learn from them. Information on the organization and implementation of geriatric care and geriatric education programs might lead to interventions designed to improve the quality of prescribing provided to older Veterans. Additionally, the clinical outcomes of those who receive potentially inappropriate medications should be closely examined, and the robust data within VA allows for this kind of examination. The potential clinical implications of this substantial variation are profound, since older patients may find themselves more or less at risk in their prescription use depending on where they reside and where they receive their care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a VA Career Development Award (CDA 09-207), a VA Health Services Research and Development grant (IIR 06-062), National Institute of Aging grants (P30AG024827, T32 AG021885, K07AG033174, R01AG034056, R56AG027017), a National Institute of Nursing Research Grant (R01 NR010135) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grants (R01 HS017695, R01 HS018721, and K12 HS019461). We acknowledge the contribution of Chen-Pin Wang in assisting with statistical analyses.

Funding: Dr. Gellad was supported by a VA Career Development Award (CDA 09-207), and Drs. Pugh, Hanlon and Ms. Amuan by a VA Health Services Research and Development grant (IIR 06-062). Dr Marcum was supported by a National Institute of Aging training grant (T32 AG021885). Dr Hanlon was additionally supported by National Institute of Aging grants (P30AG024827, K07AG033174, R01AG034056, R56AG027017), a National Institute of Nursing Research Grant (R01 NR010135) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grants (R01 HS017695, R01 HS018721, and K12 HS019461).

Dr. Pugh has received research funding from VA HSR&D DHI 09-237 (PI); VA HSR&D IIR-06-062 PI, Epilepsy Foundation PI, VA HSRD PPO 09-295 PI, VA HSR&D IIR 02-274 PI. Pugh as co-I: VA HSR&D IIR 08-274, VA HSR&D SDR-07-042, IIR-05-121, IAF-06-080, IIR-09-335, SHP 08-140, TRX 01-091 Department of Defense CDMRP 09090014, NIH R01-NR010828, Pugh Speaker Honoraria: 2009 Kelsey Seybold Research Foundation $400.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

All authors are employed by the Department of Veterans Affairs. This study was funded in part by VA HSR&D IIR 06-062.

Author Contributions:

Dr. Gellad contributed to concept and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Dr. Good contributed to concept and design of the study, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Ms. Amuan contributed to acquisition of data, analysis of data, and preparation of manuscript. Dr. Marcum contributed to design of the study, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Dr. Hanlon contributed to design of the study, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Dr. Pugh contributed to concept and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The research’s sponsor had no role or influence in matters relating to research design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beers MH, Ouslander JG. Risk factors in geriatric drug prescribing. A practical guide to avoiding problems. Drugs. 1989;37:105–112. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198937010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammerlein A, Derendorf H, Lowenthal DT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in the elderly. Clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;35:49–64. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199835010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: The prescribing cascade. BMJ. 1997;315:1096–1099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrischilles EA, VanGilder R, Wright K, et al. Inappropriate medication use as a risk factor for self-reported adverse drug effects in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1000–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fick DM, Mion LC, Beers MH, et al. Health outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:42–51. doi: 10.1002/nur.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund BC, Carnahan RM, Egge JA, et al. Inappropriate prescribing predicts adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:957–963. doi: 10.1345/aph.1m657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CM, Liu PY, Yang YH, et al. Use of the Beers criteria to predict adverse drug reactions among first-visit elderly outpatients. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:831–838. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, et al. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:562–570. doi: 10.1016/S1543-5946(10)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitrow MS, Airaksinen MS, Kivela SL, et al. Comparison of prescribing criteria to evaluate the appropriateness of drug treatment in individuals aged 65 and older: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1521–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jano E, Aparasu RR. Healthcare outcomes associated with beers’ criteria: A systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:438–447. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund BC, Steinman MA, Chrischilles EA, et al. Beers criteria as a proxy for inappropriate prescribing of other medications among older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:1363–1370. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passarelli MC, Jacob-Filho W, Figueras A. Adverse drug reactions in an elderly hospitalised population: Inappropriate prescription is a leading cause. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:767–777. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockl KM, Le L, Zhang S, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate prescribing in the elderly. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:e1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert SM, Colombi A, Hanlon J. Potentially inappropriate medications and risk of hospitalization in retirees: Analysis of a US retiree health claims database. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:407–415. doi: 10.2165/11315990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindblad CI, Hanlon JT, Gross CR, et al. Clinically important drug-disease interactions and their prevalence in older adults. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crownover BK, Unwin BK. Implementation of the Beers criteria: Sticks and stones--or throw me a bone. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11:416–417. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.5.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh MJ, Rosen AK, Montez-Rath M, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: Effects of geriatric care at the patient and health care system level. Med Care Feb. 2008;46:167–173. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158aec2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pugh MJ, Hanlon JT, Wang CP, et al. Trends in use of high risk medications for older veterans: 2004-2006. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1891–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugh MJ, Starner CI, Amuan ME, et al. Exposure to potentially harmful drug-disease interactions in older community-dwelling veterans based on the healthcare effectiveness data and information set quality measure: Who Is at Risk? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1673–1678. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the department of veterans affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl_2):B10–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning . VHA Enrollment, Patients and Expenditures. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Intranet Site; Washington, D.C.: [Accessed Sept 1, 2009]. [Accessed September 1, 2009]. 2008. Available at http://vaww.va.gov/vhaopp/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Quality Assurance [Accessed August 1, 2011];HEDIS 2008 Final NDC Lists. http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/598/default.aspx.

- 23.Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture . Rural Urban Commuting Area Code. Washington, D.C.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WWMAI Rural Health Research Center . ZIP Code RUCA Approximation Methodology. Seattle, Washington: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Hospital Association [Accessed August 1, 2011];AHA Annual Survey Database. 2005 http://www.ahadata.com/ahadata/html/AHASurvey.html.

- 26.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pugh MJ, Hanlon JT, Zeber JE, et al. Assessing potentially inappropriate prescribing in the elderly Veterans Affairs population using the HEDIS 2006 quality measure. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:537–545. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.7.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohn MW, Zhang H, Arnold N, et al. Transition to the new race/ethnicity data collection standards in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selim AJ, Fincke G, Ren XS, et al. Comorbidity assessments based on patient report: results from the Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27:281–295. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selim AJ, Kazis LE, Rogers W, et al. Risk-adjusted mortality as an indicator of outcomes: comparison of the medicare advantage program with the Veterans’ Health Administration. Med Care. 2006;44:359–365. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000204119.27597.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pugh MJ, Cramer J, Knoefel J, et al. Potentially inappropriate antiepileptic drugs for elderly patients with epilepsy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Mar;52(3):417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh MJ, Vancott AC, Steinman MA, et al. Choice of initial antiepileptic drug for older veterans: Possible pharmacokinetic drug interactions with existing medications. J Am Geriatr Socr. 2010;58:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al. Risk-adjusted mortality rates as a potential outcome indicator for outpatient quality assessments. Med Care. 2002;40:237–245. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Accessed April 2, 2011];SAS/STAT(R) 9.3 User’s Guide. http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63962/HTML/default/viewer.htm#sta tug_glimmix_a0000001407.htm.

- 36.Dai J, Li Z, Rocke D. [Accessed April 1, 2011];Hierarchical Logistic Regression Modeling with SAS GLIMMIX. 2006 http://www.lexjansen.com/wuss/2006/Analytics/ANL-Dai.pdf.

- 37.Zhang Y, Baicker K, Newhouse JP. Geographic variation in the quality of prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1985–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, et al. Reporting clinical trial results to inform providers, payers, and consumers. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1571–1581. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahian DM. Improving cardiac surgery quality--volume, outcome, process? JAMA. 2004;291:246–248. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahian DM, Normand SL. The volume-outcome relationship: From Luft to Leapfrog. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1048–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, et al. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1825–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLeod PJ, Huang AR, Tamblyn RM, et al. Defining inappropriate practices in prescribing for elderly people: A national consensus panel. CMAJ. 1997;156:385–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]