Abstract

Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD) is a lysosomal storage disorder characterized by the pathologic accumulation of sphingomyelin in multiple cells types, and occurs most prominently within the liver, spleen and lungs, leading to significant clinical disease. Seventeen ASMD patients underwent a liver biopsy during baseline screening for a Phase 1 trial of recombinant human acid sphingomyelinase (rhASM) in adults with Niemann-Pick disease type B. Eleven of the 17 were enrolled in the trial and each received a single dose of rhASM and underwent a repeat liver biopsy on Day 14. Biopsies were evaluated for fibrosis, sphingomyelin accumulation and macrophage infiltration by light and electron microscopy. When present, fibrosis was periportal and pericellular, predominantly surrounding affected Kupffer cells. Two baseline biopsies exhibited frank cirrhosis. Sphingomyelin was localized to isolated Kupffer cells in mildly affected biopsies and was present in both Kupffer cells and hepatocytes in more severely affected cases. Morphometric quantification of sphingomyelin storage in liver biopsies ranged from 4–44% of the microscopic field. Skin biopsies were also performed at baseline and Day 14 in order to compare the sphingomyelin distribution in a peripheral tissue to that of liver. Sphingomyelin storage was present at lower levels in multiple cell types of the skin, including dermal fibroblasts, macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and Schwann cells. This Phase 1 trial of rhASM in adults with ASMD provided a unique opportunity for a prospective assessment of hepatic and skin pathology in this rare disease and their potential usage as pharmacodynamic biomarkers.

INTRODUCTION

Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD) is a lysosomal storage disorder that is also known as Niemann-Pick disease (NPD) types A (NPD-A) and B (NPD-B), which correspond to two ends of a clinical spectrum resulting from deficiency of the same enzyme activity9. NPD-A is an infantile-onset disease characterized by failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly, neurodegeneration, and death in early childhood. NPD-B has variable ages of onset, heterogeneous symptoms, little to no neurologic involvement, and survival into adolescence and adulthood 6, 21. Due to the deficiency of ASM enzyme activity, its substrate, sphingomyelin (SM), accumulates within lysosomes. Pathologic accumulation of SM occurs most prominently within the monocyte/macrophages cell lineage of the reticuloendothelial system, resulting in hepatosplenomegaly, interstitial lung disease, and bone marrow infiltration 8, 19. This cellular accumulation begins in utero, as demonstrated by the 4-fold and 2.5-fold increases in hepatic and splenic SM, respectively, observed in a 12 week old ASMD fetus 18.

Prior to the development of more specific enzymatic and molecular assays, biopsy of various tissues was used to aid in the diagnosis of lysosomal storage diseases 1. However ideal fixation and staining of these specimens was not usually achieved, since routine paraffin processing of these tissues results in a non-specific vacuolated appearance and the loss of the specific substrate deposits. The inclusion of liver and skin biopsies as part of the protocol for a Phase 1 trial of recombinant human acid sphingomyelinase (rhASM) in adults with NPD-B provided a unique opportunity to prospectively analyze biopsy tissues. Optimal collection, preservation, processing and staining of tissues was ensured by applying novel processing and staining techniques that were developed and validated (Taksir et al, manuscript submitted) in an ASM knock-out mouse model 2.

In this communication we report the findings from a comprehensive histologic characterization of liver and skin biopsy specimens from patients with NPD-B, using standard methods as well as high resolution light microscopy (HRLM) for quantification of SM content by computer morphometry, and electron microscopy (EM) to confirm the presence and cellular localization of stored SM. Successful use of biopsy pathology as a biomarker of efficacy has been demonstrated previously in studies of Fabry Disease 14, 15, 17 and Pompe Disease 4, 16. In this Phase 1 study, we evaluated the biopsy pathology of ASMD in both liver and skin samples, and we assessed their utility as biomarkers of safety and disease burden for the present and future trials.

METHODS

Study design and Human Subjects

A Phase 1 trial of recombinant human acid sphingomyelinase (rhASM) in adults with Niemann-Pick disease (NPD) type B that included baseline and Day 14 liver and skin biopsies was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All patients gave written informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. Inclusion criteria for enrollment in the study were: 18 to 65 years of age, confirmed deficiency of ASM enzyme activity, spleen volume ≥ 2 multiples of normal (MN, based on a normal spleen volume of 0.2% of body weight), diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) >30% predicted, serum AST and ALT ≤ 250 IU/L, bilirubin ≤ 3.6 mg/dL, International Normalized Ratio ≤ 1.5, and platelet count ≥ 60,000/μL. Exclusion criteria included histopathologic evidence of cirrhosis, and use of agents known to be hepatotoxic, promote bleeding, or inhibit rhASM. All patients tested negative for hepatitis A, B and C, and none had a history of alcohol abuse.

Since histopathologic evidence of cirrhosis on Baseline liver biopsy was an exclusion criterion for participation in the trial, 17 adult patients with ASMD ranging in age from 18 to 54 years underwent Baseline core biopsies of liver and 3-mm punch biopsies of skin during screening. Two patients were excluded due to cirrhosis, and a third for the presence of inflammatory foci; three others were excluded for other reasons. Eleven eligible patients were assigned to one of five dose cohorts of a single dose of intravenous rhASM (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, and 1.0 mg/kg) and had repeat liver and skin biopsies at Day 14 post-dose. There were no significant changes post-dose except for one Day 14 liver biopsy with two small inflammatory foci, one with hepatocyte degeneration, classified as an adverse drug reaction.

Fresh liver samples were divided and placed into 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) and a fresh mixture of 2% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in 0.2 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3 for histopathological analyses. A separate piece was frozen in liquid nitrogen for biochemical analysis of sphingomyelin (SM). Punch biopsies of skin were preserved in 2% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in 0.2 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3. Gross photos of fixed biopsies were taken prior to processing.

Paraffin processing of liver biopsies for special stains and immunohistochemistry

The liver biopsy specimens that were immersion-fixed in 10% NBF were dehydrated in ascending grades of reagent alcohol, cleared in xylenes, infiltrated and embedded into Paraplast X-TRA paraffin (McCormick Scientific, LLC; St. Louis, MO) on a Tissue-Tek VIP tissue processor (Sacura Finetek Japan Co.; Tokyo, Japan). Five-micron sections were cut on a Leica microtome and mounted onto Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus Slides (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA). Slides were stained with modified hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome and Gordon-Sweets’s reticulin stains according to standard methods 10. Immunohistochemistry for the macrophage-specific marker, CD68, was performed using a mouse anti-human CD68 antibody (Dako, clone PG-M1, cat# M0876) at a concentration of 0.4 μg/mL. Slides were stained with Dako diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromagen solution and a hematoxylin counterstain (Dako, Carpinteria, CA).

Tissue processing for high resolution light microscopy (HRLM) and electron microscopy (EM)

One-millimeter cubes of each tissue specimen were fixed for a minimum of 24 hours in 2% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.2 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3. The tissues were then washed in 0.2 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer overnight and placed in a working solution of 2.5% potassium dichromate and 0.5% osmium tetroxide in RO/DI water for 6 hours at room temperature, followed by washing in running water for 1 hour. The tissues were then stored overnight in 30% ethanol at 4°C, followed by dehydration in acetones (70%, 100% acetones for 30 minutes each). After dehydration the tissues were infiltrated in 70% resin [15ml DDSA, 5ml LX-112, 5ml Araldite 502, and 0.5ml DMP-30 (Ladd Research Industries; Williston, VT)] in acetone for 1 hour. Tissue was then infiltrated in 2 changes of 100% resin, one at 3 hours and one overnight. Embedding was performed in “00” Beem capsule with 100% resin and polymerized at 60°C for a minimum of 48 hours. One micron sections were cut using a Leica EM UC6 microtome (Leica Microsystems) with an ultra-diamond knife (Diatome; Hatfield, PA). The sections were collected on Superfrost Plus Slides and dried overnight on a 40°C slide warmer.

Modified toluidene blue staining of epon-araldite sections for high resolution light microscopy (HRLM)

Slides were hydrated in water for one minute. The slides were then treated with a filtered solution of 0.5% of tannic acid in Ringer’s solution buffer, pH 6.8 (Electron Microscopy Sciences; Hatfield, PA) for 15 minutes, followed by rinsing in running water for 5 minutes. Slides were then stained for 2 minutes with a 1% solution of toluidine blue/borax pH 8.4 (heated to 60°C). After staining, sections were washed in running water for 5 minutes and then dried completely in a 60°C oven and coverslipped with TBS SHUR/Mount Xylene-Based Mounting Medium Medium (Triangle Biomedical Systems, Inc; Durham, NC). When performed successfully, the areas containing SM stain purple, nuclei stain dark blue and cytoplasm and other elements stain light blue. The distinct color contrast thus renders these slides suitable for MetaMorph image analysis.

Lysenin affinity staining on epon-araldite sections

Epon sections were hydrated in tris buffered saline (TBS) (DAKO; Carpinteria, CA) with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T, DAKO) for 5 minutes. For SM staining, a 5μg/mL solution of lysenin protein (Peptides International; Louisville, KY) was diluted in TBS with 0.5% BSA (TBS-B, DAKO) and placed on the slides and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After rinsing in TBS-T, a 1:2500 dilution of rabbit anti-lysenin antiserum (Peptides International, Louisville, KY) diluted in TBS-B was added to the slides for 30 min at RT. Following another TBS-T rinse, MACH2 rabbit ALP (alkaline phosphatase) polymer (Biocare Medical; Concord, CA) was applied for 30 minutes at RT. After rinsing in TBS-T, slides were developed in Vulcan Fast Red chromagen (Biocare Medical) and counterstained in a 1:10 dilution of Richardson’s stain (heated to 60°C) for 15 seconds. Once thoroughly rinsed in running tap water, the slides were air dried, mounted with TBS SHUR/Mount Xylene-Based Mounting Medium (Triangle Biomedical Systems, Inc; Durham, NC) and coverslipped. Using this method, SM appeared red against a light blue background.

Transmission electron microscopy

Seventy nm ultrathin sections were cut from liver and skin epon blocks and mounted on 200-mesh copper grids. The grids were stained with Leica EM Stain (Leica Microsystems) containing 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate and 3% lead citrate solution. Images were acquired on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL; Peabody, MA) using a Gatan 785 Erlangshan ESW1000 digital camera (Gatan, Inc.; Pleasanton, CA).

MetaMorph® digital analysis

MetaMorph analysis was performed as described elsewhere 4. Briefly, one representative field from each slide was photographed with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera and acquired with the Nikon Act 1 photo image capture software for the DXM1200 digital camera, version 1.12 (Nikon Inc., Instrument Group, Melville, NY). Each digital image was photographed with the 60× objective and formatted at a fixed pixel density (8 × 10 inches at 150dpi) using Adobe PhotoShop software (version 5.5). Each digital image was then opened using the MetaMorph® Imaging Processing and Analysis software (version 6.3, Universal Imaging Corporation) for histomorphometric analysis.

MetaMorph was used to quantify the amount of SM staining as a percentage of total tissue area in each digital image. The area of total tissue (designated as IMAGE A and represented by purple and blue staining together) and the area occupied by SM (designated as IMAGE B and represented by purple staining only) were calculated in terms of pixels. The co-localization function of MetaMorph then calculated the percentage of pixels in common between IMAGE A and IMAGE B and automatically exported the calculation into an Excel spreadsheet.

Up to 10 blocks were produced from each patient liver biopsy (sample size permitting). One section from each block was cut, stained, mounted on a slide and analyzed as described above. This ‘breadloaf’ approach ensured the evaluation of SM in up to 10 slides representative of the distribution across the entire length of sample. The average and standard deviation were calculated from each set of sections.

Biochemical analysis of sphingomyelin (SM)

Liver biopsy samples were cut into approximately 1×1×5mm pieces, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C until processed. Each piece of tissue was subsequently extracted twice with 0.5 mL of chloroform:methanol (2:1) solvent, homogenized for 30 seconds using a sonic homogenizer and the final 1.0mL incubated for 15 minutes at 37 °C on a rocking platform. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation and 200uL of water was added to each sample tube. The samples were vortexed and centrifuged (5 min at 16,100g) to separate the phases. The top aqueous phase was analyzed for total protein concentration using the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific-Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were interpolated using a bovine serum albumin standard curve (Thermo Scientific-Pierce). The bottom organic phase was used for SM quantification. This organic phase was dried under nitrogen, re-suspended and then cleaned up by liquid-liquid extraction. SM contains a long chain fatty acid of varying lengths and degrees of saturation. Therefore SM levels can be reported as a summation of these isoforms (total SM). Each isoform was quantified by mass spectrometry (MS). Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode MS/MS technique using a structure-specific product ion (m/z 184) from the phosphorylcholine head group from SM isoforms was used to measure total SM concentrations. Sphingomyelin isoforms were separated by Liquid Chromatography (LC) before being subjected to MS/MS analysis. Because of the high SM concentration present, the liver samples were diluted at 1/10, 1/50, 1/500 and tested for SM at all dilutions to ensure that at least one dilution was within the standard curve quantification range. Due to lack of human liver matrix, a methanol standard curve was used in clinical sample testing. Comparability between liver matrix curve and methanol curve was established. The standard curve (signal as ratio of standard/internal standard vs. SM concentration at 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, and 5 μg/mL) used linear curve fit with 1/x weighting. Sample signal was interpolated from the standard curve to generate SM concentration values. Sphingomyelin concentration was normalized to tissue protein concentration (μg SM/mg protein) determined by BCA.

Biochemical analysis of ASM activity in patient fibroblasts

Acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) activity in lysates of cultured dermal fibroblasts from patient skin biopsies was measured using the Amplex Red kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, Catalog# A12220). The assay was performed in two steps. First, ASM hydrolyzed the natural substrate (sphingomyelin) in acetate buffer at PH 5.0 to yield ceramide and phosphorylcholine. In the 2nd step, a Tris solution containing three additional enzymes (alkaline phosphatase, choline oxidase and horseradish peroxidase) and a second substrate (Amplex Red) was added to the reaction mix to terminated the first reaction and produce a fluorescent product (resorufin) from the phosphorylcholine. The amount of fluorescence was compared to that produced from known quantities of resorufin in a standard curve. Consequently, the amount of fluorescence was directly proportional to the amount of ASM present in the sample. The normal range for ASM activity in normal adult cultured fibroblasts was determined to be 84.9–402.4 nmol/hr/mg. The Below Assay Quantitation Limit (BQL) was defined as < 2.7 nmol/hr/mg.

Statistical Methods

In order to assess correlations between variables such as baseline age, degree the splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, SM storage by morphometry, biochemical measurements of SM, changes and percentages in these variables and rhASM dose, Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values were computed.

RESULTS

Liver biopsy pathology

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver biopsies were assessed for fibrosis according to the Laennec scoring system 7, which grades the extent of fibrosis on a scale from 0–4 (0, no fibrosis; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, cirrhosis). Two of the 17 patients (12%) had scores of 0. The remaining 15 patients (88%) had evidence of fibrosis as follows: grade 1, 5 patients (29%); grade 2, 6 patients (35%); grade 3, 2 patients (12%); and grade 4, 2 patients (12%) (Table 1). Since cirrhosis was an exclusion criterion, the latter two patients (ages 39 and 40) were excluded from the remainder of the Phase 1 trial per protocol.

Table 1. Summary of Patient Characteristics.

Summary of patient number, age, fibrosis score, residual enzyme levels, Metamorph measurement for hepatic SM pre- and post-treatment, biochemical measurement of hepatic SM and baseline liver and spleen sizes (as multiples of normal).

| Patient Number | Dose Group | Age at Baseline (Years) | Baseline Liver Fibrosis Score | ASM Activity in Fibroblasts (nmol/hr/mg protein) | Baseline Spleen Volume (Multiples of Normal) | Baseline Liver Volume (Multiples of Normal) | Baseline Liver SM by MetaMorph (% Tissue Area) | Baseline Liver SM by MS/MS (μg/mg protein) | Day 14 Liver SM by MetaMorph (% Tissue Area) | Day 14 Liver SM by MS/MS (μg/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.03 mg/kg | 24 | 3 | 4.2 | 12.5 | 1.7 | 41.2±9.6 | 7,453 | 37.9±18.7 | 4,558 |

| 2 | 0.03 mg/kg | 22 | 2 | 5.6 | 15.1 | 2.1 | 27.3±5.0 | 8,264 | 33.5±4.7 | 6,786 |

| 3 | 0.03 mg/kg | 20 | 2 | 4.7 | 16.1 | 2.1 | 20.9±4.0 | NA* | 41.0± 8.8 | 5,422 |

| 4 | 0.1 mg/kg | 46 | 0 | 26.7 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 2.7±2.0 | NA* | 3.6±1.2 | NA* |

| 5 | 0.1 mg/kg | 26 | 1 | 3.5 | 12.3 | 2.0 | 35.8±11.2 | 6,475 | 44.0±6.7 | 14,588 |

| 6 | 0.1 mg/kg | 42 | 0 | 17.5 | 8.7 | 1.2 | 5.6±1.4 | 533 | 6.4±2.7 | 519 |

| 7 | 0.3 mg/kg | 24 | 2 | <2.7 | 9.5 | 1.6 | 28.6±6.1 | NA* | 17.5±3.8 | NA* |

| 8 | 0.3 mg/kg | 54 | 2 | NA | 6.1 | 1.2 | 29.5±5.0 | NA* | 22.6±5.3 | 5,471 |

| 9 | 0.6 mg/kg | 18 | 1 | <2.7 | 8.7 | 1.2 | 18.4±7.2 | NA* | 16.2±2.0 | 2,720 |

| 10 | 0.6 mg/kg | 18 | 1 | 12.4 | 10.1 | 1.7 | 23.2±2.0 | 4,816 | 22.8±4.4 | 6,971 |

| 11 | 1.0 mg/kg | 46 | 2 | 11 | 14.5 | 1.5 | 30.2±6.1 | 5,290 | 21.3±5.0 | 3,151 |

| 12 | screened but not dosed | 41 | 2 | 6.3 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 15.8±6.9 | NA* | NA | NA |

| 13 | screened but not dosed | 38 | 3 | 5.4 | 8.7 | 0.9 | 8.9±2.8 | NA* | NA | NA |

| 14 | screened but not dosed | 24 | 1 | <2.7 | 9.7 | 1.9 | 44.6±8.1 | 2,886 | NA | NA |

| 15 | screened but not dosed | 19 | 1 | 12.8 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 43.6±5.9 | NA* | NA | NA |

| 16 | excluded | 41 | 4 | 2.7 | 13.0 | 2.1 | 39.8±14.7 | 13,567 | NA | NA |

| 17 | excluded | 39 | 4 | 11 | 15.9 | 1.9 | 31.8±12.5 | NA* | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, measurement not performed; NA*, biochemical measurement not available due to protein concentration out of range for the assay. The Adult Normal Fibroblast ASM Activity Range was defined as 84.9–402.4 nmol/hr/mg. The Below Assay Quantitation Limit (BQL) was defined as < 2.7 nmol/hr/mg.

Figure 1 compares the histopathology of two representative liver biopsies with grade 0 (no fibrosis) and grade 4 (cirrhosis), respectively. The biopsy in Figure 1A (Patient 6) exhibited relatively undisturbed hepatocellular architecture on reticulin stained sections and the corresponding trichrome stain demonstrated the absence of fibrosis (Figures 1C); sphingomyelin-laden Kupffer cells presented as single cells within sinusoids (arrows). Conversely, the cirrhotic biopsy in figure 1B (Patient 16) demonstrated marked distortion of the normal lobular architecture throughout the specimen on reticulin stained sections. Trichrome stained sections (Figure 1D) showed the pericellular fibrosis which develops around large swaths of Kupffer cells near portal areas.

Figure 1. Assessment of liver biopsies for fibrosis.

A. Patient 6: liver biopsy with fibrosis grade of zero. Reticulin stain highlights the normal hepatocellular architecture (10× objective). B. Patient 16: liver biopsy with fibrosis grade of 4 (cirrhosis). Reticulin highlights the collapse of the hepatic sinusoidal architecture and the formation of nodules (10× objective). C. Trichrome stained section of biopsy from Patient 6. Note the absence of fibrosis and the presence of isolated, SM-laden Kupffer cells (arrows), features characteristic of mildly affected biopsies (40× objective). D. Trichrome stained section of biopsy from patient 16. Note the pericellular fibrosis which accompanies the formation of large swaths of Kupffer cells, a common feature in more severely affected biopsies (40× objective).

Liver Sphingomyelin Content

The 17 baseline liver biopsies had variable amounts of SM accumulation. The cell-specific localization of SM varied depending on the total amount of SM staining and specific distribution patterns were noted. In the two patients (Patients 4 and 6) with the lowest levels of SM staining, the cellular distribution was largely limited to sinusoidal Kupffer cells (K distribution) which appeared as enlarged foamy cells present in sinusoids on H&E stained sections (Figure 2A, Patient 6). Of interest, these two patients also had the highest levels of residual ASM activity as measured in the fibroblast assay (Table 1). In epon-embedded samples, SM was preserved within Kupffer cells and stained purple with the modified toluidene blue (Figure 2C) and red with the lysenin affinity stain (Figure 2E). Immunohistochemistry staining for the macrophage marker, CD68, highlights the K distribution in Figure 2G.

Figure 2. Sphingomyelin load and cell distribution vary amongst patient biopsies.

In some biopsies, SM is present in sinusoidal Kupffer cells only (K distribution). In other biopsies, SM has accumulated in sinusoidal Kupffer cells, foci of proliferating portal Kupffer cells and hepatocytes (KH distribution). A. Patient 6: SM is present within enlarged, foamy Kupffer cells (arrows; H&E, 60× objective). B. Patient 1: SM is present within clusters of enlarged foamy Kupffer cells (K) and foamy hepatocytes (H) (H&E, 60× objective). C. In HRLM sections, SM stains purple in sinusoidal Kupffer cells (modified toluidine blue, 100× oil objective). D. In KH distribution, SM is present in both Kupffer cells and hepatocytes (modified toluidine blue, 100× oil objective). E and F. Lysenin affinity staining also highlights the differences in SM accumulation in K versus KH distribution patterns (lysenin affinity stain, 100× oil objective). G. CD68 immunohistochemistry highlights the enlarged Kupffer cells as single cells (10× objective). H. CD68 immunohistochemistry highlights enlarged Kupffer cells as single cells and as clusters proliferating in portal tracts and infiltrating bands of fibrosis (10× objective).

In the remaining 15 biopsies, higher amounts of SM staining were visible within large swaths of Kupffer cells in portal areas as well as within hepatocytes across the entire biopsy (KH pattern). H&E stained sections from these 15 samples demonstrated hepatocytes with a finely vacuolated cytoplasm (lysosomal storage) throughout the specimen along with multiple clusters of foamy Kupffer cells (e.g. Figure 2B, Patient 1). Figures 2D and 2F illustrate the toluidene blue and lysenin affinity staining of SM in both cell types. In Figure 2H, immunohistochemical staining for CD68 clearly shows the enlarged Kupffer cells present as single cells within the sinusoids, as well as the proliferation of additional SM-laden Kupffer cells, which clustered and infiltrated bands of fibrosis near portal areas.

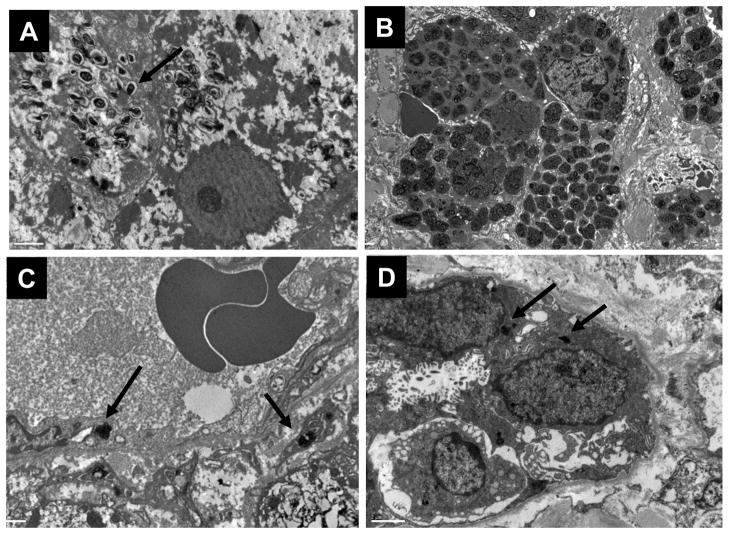

Electron microscopy of liver biopsies

Lysosomal accumulation of SM was confirmed in hepatocytes (Figure 3A) and in clusters of Kupffer cells by electron microscopy (Figure 3B). In hepatocytes, lysosomes were enlarged by the SM storage which appeared as small zebra bodies and loose myelin figures scattered throughout the cytoplasm. In Kupffer cells, lysosomal SM storage appeared as large, tight myelin figures packed side by side and occupying nearly the entire volume of the cell. Electron microscopy also revealed low levels of SM accumulation in sinusoidal endothelial cells (Figure 3C) and bile duct epithelial cells (Figure 3D), which were not visible at the light microscopy level.

Figure 3. Electron microscopy of lysosomal sphingomyelin in liver biopsies.

A. Sphingomyelin is present in hepatocytes as scattered zebra bodies and loose myelin figures (15000×). B. In Kupffer cells, SM packs the cell cytoplasm as dense myelin figures (5000×). C. Sinusoidal endothelial cells contain dense foci of SM (12000×). D. Bile duct epithelium also contains SM (8000×)

MetaMorph analysis of hepatic sphingomyelin levels, pre- and post-rhASM infusion

MetaMorph quantification of SM storage is shown in Figure 4A. At Baseline 2.7 % to 44.6 % of total tissue area was occupied by SM (Figure 4B and Table 1), with a mean of 26.3 ± 13.0%. Note that the biopsies from Patients 4 and 6 had the lowest levels of SM accumulation, which was limited to Kupffer cells. In the adjacent liver samples frozen at the time of biopsy, SM levels measured biochemically ranged from 533 to 13,567 μg/mg protein. The degree of SM storage by morphometry correlated with the biochemical measurement of SM at Day 14 post-infusion (r = 0.73; p = 0.02) but not at Baseline (r = 0.53; p = 0.18), which may be due to sampling variability, methodology differences and the small number of samples available for biochemical evaluations (N=8–9). The degree of SM storage by morphometry also correlated with the degree of hepatomegaly (r = 0.59; p = 0.01), and trended with the degree of splenomegaly (r = 0.45; p = 0.07), both of which are clinical indicators of lysosomal storage. The degree of SM storage by morphometry correlated inversely with the amount of residual ASM activity in fibroblasts (r = −0.52; p = 0.04) such that lower activity was associated with more SM accumulation. MetaMorph quantification of SM in Baseline and post-infusion biopsies suggested a trend toward SM reduction after a single infusion at higher doses (r = −0.57; p=0.07). Notably there was no correlation between SM levels and either fibrosis grade or patient age. Like SM (by morphometry), the Baseline fibrosis grade also appeared related to spleen volume (r = 0.48; p = 0.05) and ASM activity (r = −0.49; p = 0.05) but unlike SM, not to liver volume (r = 0.33; p = 0.19). Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly showed a high correlation (r = 0.80; p < 0.01). It should be noted that, in addition to SM accumulation in splenic macrophages, the portal hypertension reported in Niemann-Pick patients may also, in part, contribute to splenomegaly 8,13.

Figure 4. Quantification of hepatic sphingomyelin in HRLM sections by Metamorph® Analysis.

A. Sphingomyelin can be quantified in liver biopsies with HRLM processing and MetaMorph® analysis. B. Metamorph® bar graph of Baseline levels of SM, solid bars. Post-infusion levels are indicated as hatched bars, when available.

Isolated liver observations

The appearance of the Baseline biopsy from Patient 13 (Figures 5C and D) deviated notably from the typical fine pericellular fibrosis around the foamy Kupffer cell infiltration typically observed in most of our liver biopsies (Figure 5A and B). This biopsy contained two prominent lymphoid aggregates (Figure 5C) in association with distinct foci of dense periportal fibrosis (staining intense blue on trichrome stained sections, Figure 5D) devoid of foamy cell infiltration, although foamy Kupffer cells and finely vacuolated hepatocytes were scattered throughout the rest of the hepatic parenchyma. These dense, fibrotic, inflammatory lesions were not observed in any other Baseline biopsy. The patient was noted to have a prior history of prescription medications with known hepatotoxicity. Therefore, these foci may represent an unrelated, pre-existing secondary process, such as a chronic drug-induced hepatitis.

Figure 5. Isolated liver observations.

A. This image shows the typical appearance of the portal and pericellular fibrosis of the foamy cell infiltration (arrows) that is present in the majority of biopsies in this study (H&E, 40× objective). B. Trichrome stained section of same area in A highlights the fine, loose appearance of pericellular fibrosis around foamy Kupffer cells (40× objective). C. In contrast, patient 13 baseline biopsy contained dense periportal fibrosis with infiltration of lymphocytes (H&E, 40× objective). D. Trichrome stain of the same region in A shows blue staining of the dense fibrosis which is devoid of foamy cell infiltration (trichrome, 40× objective). E. Patient 10 post-treatment biopsy contains small lymphocytic foci with hepatocellular degeneration (H&E, 40× objective). F. Trichrome stain of the same region in C showing hyperchromasia in the region of hepatocellular degeneration (trichrome, 40× objective).

The post-infusion biopsy from Patient 10 (0.6 mg/kg rhASM) contained a 0.5 mm diameter focus of lymphocytic infiltrate associated with hepatocellular degeneration (Figure 5E). The focus of hepatocellular degeneration appeared hyperchromatic on trichrome stained sections (Figure 5F). A second 0.1 mm cluster of lymphocytes was also present, but was not associated with hepatocellular degeneration. These inflammatory and degenerative changes were not observed in the patient’s Baseline biopsy, and consequently, this post-treatment change was reported as a mild adverse drug reaction.

Sphingomyelin accumulation in skin biopsies

The amount of SM staining in skin was much lower than that in liver. All samples had < 1% of the tissue area involved. These low levels of SM were more easily detected with the lysenin affinity-staining method, where the red chromagen provided greater contrast against the blue counterstain (Figure 6A and 6B). Sphingomyelin storage was present in multiple cell types, including dermal fibroblasts, macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, perineurium, and Schwann cells as confirmed by electron microscopy (Figure 6C through 6F). There were no qualitative differences in SM accumulation in post-infusion skin biopsies.

Figure 6. Sphingomyelin accumulates in multiple cell types of the skin.

A. Sphingomyelin is present in fibroblasts (arrowhead) and macrophages (black arrow) of the superficial dermis (red lysenin affinity stain for SM, toluidine blue counterstain, 60× objective). B. Sphingomyelin can also be identified in endothelial cells and pericytes of capillaries in the deep dermis between adipocytes (red lysenin affinity stain for SM, toluidine blue counterstain, 60× objective). C. Electron microscopy of SM in dermal fibroblast (white arrow; 15000×). D. Electron microscopy of SM in dermal capillary endothelial cells (arrowhead) and pericytes (white arrow) (12000×). E. Electron microscopy of SM in dermal macrophage (white arrow, 25000×). F. Sphingomyelin was also present within small nerves (12000×).

DISCUSSION

This Phase 1 study provided a unique opportunity to prospectively characterize the liver and skin histopathology in 17 adult patients with ASMD, with a special emphasis on characterizing the SM accumulation and its cellular distribution. “Niemann-Pick cells,” “sea-blue histocytes,” “foam cells,” and “lipid-laden macrophages” are all terms found in the historical literature to describe the iconic histologic appearance of phagocytic cells in ASMD. While macrophages of liver, spleen, lung and bone marrow are the earliest and most prominently affected cells 8, 19, this study has documented SM accumulation in other cell types including hepatocytes, bile duct epithelium, vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, perineurium and Schwann cells.

An important new finding is documentation of the presence of variable degrees of fibrosis in nearly all study patients, with progression to cirrhosis in two patients who did not have any clinical symptoms of liver failure. Previously, hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis has only been reported in a small number of severely affected young patients 3, 20. Single reports of hepatic failure 8 and GI bleeding and ascites 13 also have been previously reported. In the general population, cirrhosis is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma 7, and while hepatocellular carcinoma has occurred in a few Niemann-Pick case reports 1 (McGovern, unpublished observation), it difficult to determine whether the incidence is higher in Niemann-Pick patients.

Another important finding was the wide variability in the degree of SM accumulation, and two specific patterns of storage: patients with low levels of SM storage showed staining in isolated Kupffer cells whereas those with higher levels of SM also showed staining within hepatocytes along with the swaths of Kupffer cells associated with pericellular fibrosis. Based on the pathophysiology of the disease, NPD patients with lower amounts of residual ASM activity are expected to store greater amounts of lysosomal SM, resulting in higher SM levels in liver biopsies and larger organ volumes. These relationships were supported by the various correlation determinations. For example, the patient with the lowest liver SM level by MetaMorph analysis (2.7 % of tissue area in Patient 4) had the least liver enlargement, calculated as 1.04 multiples of normal by MRI measurement, whereas patients with higher SM levels had more pronounced liver enlargement (r = 0.59; p = 0.01; Table 1), and prominent accumulation in hepatocytes.

Surprisingly there was no correlation between SM content and fibrosis grade, and less surprisingly, no correlation between liver size and fibrosis grade, which suggests that substrate storage is not the sole determinant of the development of fibrosis in the liver. Indeed, one would expect fibrosis to have the opposite effect on liver volume as SM storage, i.e., while livers in early cirrhosis may not be shrunken, a fibrotic liver that is progressing toward end-stage cirrhosis should become smaller over time. There was however, a strong correlation between liver size and spleen size (r = 0.80; p<0.01), and additional suggestive correlations of spleen size with liver SM storage (r = 0.45; p = 0.07) and fibrosis (r = 0.48; p = 0.05) that lend further support to the use of spleen size as a global indicator of disease severity6.

As has been seen for other diseases manifestations in ASMD, patient age was not a predictor of histologic severity. Indeed the patient with the lowest SM levels was among the oldest in this trial. This finding is consistent with the significant disease heterogeneity among affected patients with ASMD which is presumed to be due to the severity of the specific underlying genetic mutations in SMPD1 and the amount of residual enzymatic activity 5, 11, 12.

The presence of SM in multiple cell types of the skin suggests that skin biopsy might also serve as a convenient, less invasive biomarker of SM clearance in instances where liver biopsy is considered too invasive. Skin biopsies have already been utilized successfully as biomarkers of substrate clearance by ERT in Fabry disease 15. The clearance of globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) from skin biopsies was monitored in parallel with GL-3 clearance from renal14 and cardiac17 biopsies in early repeat-dose trials of ERT for Fabry Disease. The clearance of GL-3 from the vascular endothelium of the skin paralleled GL-3 clearance from the vascular endothelium of kidney and heart, two key target organs of disease in Fabry Disease. This demonstrated the utility of skin biopsy as a comparatively non-invasive biomarker in instances where a treating physician might judge renal and/or cardiac biopsy as too invasive for monitoring purposes.

While the baseline levels of SM substrate in Niemann-Pick skin biopsies are less dramatic than SM levels in liver, they are similar to levels of GL-3 substrate observed in Fabry skin biopsies. By assessing SM clearance from skin and liver biopsies in parallel during future repeat dose studies of ERT for Niemann-Pick disease, we hope to determine whether skin biopsy has similar utility in reflecting the efficacy of ERT in other target organs, as was demonstrated in trials for Fabry Disease.

In summary, the extensive analysis of liver and skin pathology in a small cohort of ASMD patients reported here demonstrated the common occurrence of liver fibrosis and also served as a post-infusion safety marker. These results also suggest that quantifiable substrate pathology merits further investigation in future repeat dose studies where such biopsy analyses may serve as useful biomarkers of pharmacodynamic activity during long-term enzyme replacement therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the histology laboratory personnel in the Department of Pathology at Genzyme for the development of novel processing and staining protocols for our Niemann-Pick program, and Kefei Zheng, PhD, for development of the biochemical assay for SM by LC/MS/MS analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ASMD

acid sphingomyelinase deficiency

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- EM

electron microscopy

- ERT

enzyme replacement therapy

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HRLM

high resolution light microscopy

- NBF

neutral buffered formalin

- NPD

Niemann Pick disease

- rhASM

recombinant human acid sphingomyelinase

- SM

sphingomyelin

- SMPD1

sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 gene, acid lysosomal

- TBS

tris buffered saline

- TBS-B

TBS containing 0.5% BSA

- TBS-T

TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: BLT, FOB, SR and GFC are employees of Genzyme Corporation. This study was supported by Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA). MMM is the recipient of Mid-Career Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award K24 RR021991-01 from the National Institutes of Health. The patient studies were also supported by grant 5 MO1 RR00071 for the Mount Sinai General Clinical Research Center from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Crocker AC, Farber S. Niemann-Pick disease: a review of eighteen patients. Medicine. 1958;37(1):1–95. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horinouchi K, Erlich S, Perl DP, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase deficient mice: a model of types A and B Niemann-Pick disease. Nature Genetics. 1995;10:288–293. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labrune P, Bedossa P, Huguet P, et al. Fatal liver failure in two children with Niemann-Pick disease type B. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;13:104–109. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199107000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch CM, Johnson J, Vaccaro C, et al. High Resolution Light Microscopy (HRLM) and Digital Analysis of Pompe Disease Pathology. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53 (1):63–73. doi: 10.1177/002215540505300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGovern MM, Pohl-Worgall T, Deckelbaum RJ, et al. Lipid abnormalities in children with types A and B Niemann-Pick disease. J Pediatr. 2004;145:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGovern MM, Wasserstein MP, Giugliani R, et al. A prospective, cross-sectional survey study of the natural history of Niemann-Pick disease type b. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e341–e349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odze RD, Goldblum JR, Crawford JM, editors. Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Billiary Tract and Pancreas. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. pp. 878–882. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putterman C, Zelingher J, Shouval D. Liver failure and the sea-blue histiocyte/adult Niemann-Pick disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15(2):146–149. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuchman EH, Desnik RJ. Niemann-Pick disease types A and B: acid sphingomyelinase deficiencies. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, et al., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3589–3610. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan DC, Hrapchak BB, editors. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. 2. Columbus OH: Battelle Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonaro CM, Desnick RJ, McGovern MM, et al. The demographics and distribution of type B Niemann-Pick disease; novel mutations lead to new genotype/phenotype correlations. Am J Human Genet. 2002;71(6):1413–9. doi: 10.1086/345074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi T, Akiyama k, Tomihara M, et al. Heterogeneity of liver disorder in type B Niemann-Pick disease. Human Pathology. 1997;28(3):385–388. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tassoni JP, Fawaz KA, Johnston DE. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension in a patient with adult Niemann-Pick disease. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:567–569. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90233-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurberg BL, Rennke H, Colvin RB, et al. Globotriaosylceramide Accumulation in the Fabry Kidney is Cleared from Multiple Cell Types After Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Kidney International. 2002;62:1933–1946. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurberg BLH, Byers HR, Granter SR, et al. Monitoring the Three Year Efficacy of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Fabry Disease by Repeated Skin Biopsies. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122 (4):900–908. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thurberg BL, Lynch Maloney C, Vaccaro C, et al. Characterization of pre- and post-treatment pathology after enzyme replacement for Pompe disease. Lab Invest. 2006 Dec;86(12):1208–20. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thurberg BL, Fallon JT, Mitchell R, et al. Cardiac microvascular pathology in Fabry disease: evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies before and after enzyme replacement therapy. Circulation. 2009;118:2561–2567. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanier MT, Boue J, Dumez Y. Niemann-Pick disease type B: first-trimester prenatal diagnosis on chorionic villi and biochemical study of a foetus at 12 weeks of development. Clin Genet. 1985;28(4):348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viana MB, Giugliani R, Leite VH, et al. Very low levels of high density lipoproteín cholesterol in four sibs of a family with non-neuropathic Niemann-Pick disease and sea blue histiocytosis. J Med Genet. 1990;27:499–504. doi: 10.1136/jmg.27.8.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victor S, Coulter JBS, Besley TN, et al. Niemann-Pick disease: sixteen-year follow-up of allogenic bone marrow transplantation in a type B variant. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26:775–785. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000009950.81514.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasserstein MP, Desnick RJ, Schuchmann EH, et al. The natural history of type B Niemann-Pick disease: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e672–e677. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]