Abstract

In the absence of structural heart disease, the great majority of cases with complete congenital heart block will be associated with the maternal autoantibodies directed to components of the SSA/Ro – SSB/La ribonucleoprotein complex. Usually presenting in fetal life before 26 weeks’ gestation, once third-degree (complete) heart block develops, it is irreversible. Therefore, investigators over the past several years have attempted to predict which fetuses will be at risk for advanced conduction abnormalities by identifying a biomarker for less-severe or incomplete disease, in this case PR interval prolongation or first-degree atrioventricular block. In this state-of-the-art review, we critically analyze the various approaches to defining PR interval prolongation in the fetus, and then analyze several clinical trials that have attempted to address the question of whether complete heart block can be predicted and/or prevented. We find that, first and foremost, definitions of first-degree atrioventricular block vary, but that the techniques themselves are all similarly valid and reliable. Nevertheless, the task of predicting those fetuses at risk, and who are therefore candidates for treatment, remains challenging. Of concern, despite anecdotal evidence, there is currently no conclusive proof that a prolonged PR interval predicts complete heart block.

Keywords: anti-Ro antibodies, anti-La antibodies, congenital heart block, fetal echocardiography, maternal autoimmune disease, neonatal lupus

The development of congenital heart block in an offspring is one of the strongest clinical associations with autoantibodies directed to components of the SSA/Ro-SSB/La ribonucleoprotein complex. This concern faces 2% of primigravid mothers with these reactivities, and the risk is 10-fold higher in women who have had a prior affected child. Third-degree (complete) atrioventricular block is irreversible,1 although one case of transient reversal has been reported.2 Third-degree atrioventricular block is attributed to fibrosis and calcification or fatty replacement of the specialized cardiac conduction tissues. The outcomes are often poor, with intrauterine demise in up to a third of cases.3,4

A prevailing hypothesis assumes an orderly progression from first-degree, through second-degree, to third-degree atrioventricular block. A corollary is that if one could detect first-degree atrioventricular block in the exposed fetus, this would represent the earliest manifestation of cardiac involvement in neonatal lupus that may still be reversible with immune-modifying therapy.

The overriding goal of clinical monitoring is to predict those fetuses at risk. A secondary goal is to monitor progression as well as treatment efficacy, accurately and reliably. Several techniques have been developed recently to detect fetal first-degree atrioventricular block, a clinically silent finding manifested by a prolonged PR interval, undetectable by standard obstetrical ultrasound. These questions remain unanswered: What is the clinical significance of a prolonged fetal PR interval? Is first-degree atrioventricular block an obligate precursor to third-degree atrioventricular block? Is there a justification for immunomodulatory and/or anti-inflammatory therapy, when fetal PR prolongation is detected? Critical to answering these questions is the availability of a reliable technique for determining the fetal PR interval. Indeed, Rein and co-workers have called for an “Echocardiology-Rheumatology Consensus Statement” on the “most appropriate modality for the diagnosis of first-degree atrioventricular block” in at-risk fetuses.5 Can we develop such a consensus?

TECHNIQUES TO MEASURE FETAL PR INTERVALS

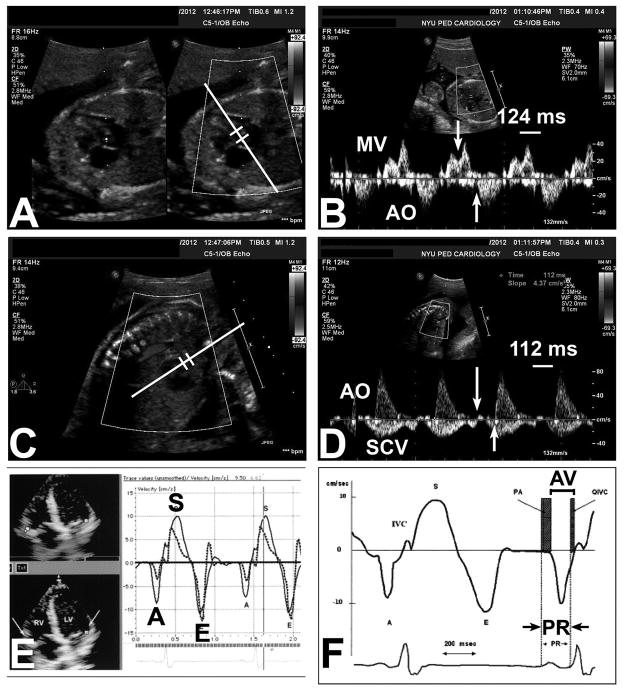

Several methods are used to measure the fetal PR interval. Most are ultrasound-derived, which represent mechanical surrogates of electrical events (Figure 1). Ultrasound techniques especially are now extensively validated; these are highly diagnostic of fetal arrhythmias and atrioventricular conduction abnormalities. The question remains: Is there a “best” technique?

Figure 1. Ultrasound-based methods to measure mechanical surrogates of the electrocardiographic P-R interval in the fetus.

A,B) Mitral-aorta pulsed-wave Doppler method; C,D) Superior caval vein-aorta pulsed-wave Doppler method; E,F) Fetal kinetocardiogram tissue Doppler method (with permission). A,B) The Mitral (MV)-aorta (AO) method relies on identification of the trans-mitral atrial inflow (A wave) and ejection out the left ventricular outflow tract. The Doppler pulsed-wave sample volume is placed near the mitral valve leaflet in the LV outflow tract (panel A), and measurement is made from the onset of the trans-mitral A wave to the onset of LV outflow tract ejection (panel B, arrows). In this case, the MV-AO P-R interval is 124 msec. C,D) The Superior caval vein (SCV)-aorta (AO) method interrogates both the caval and ascending aortic blood flow by pulsed-wave Doppler (panel C) and relies on the identification of onset of atrial “kick” reversal in the superior caval vein and aortic ejection (panel D, arrows). E,F [adapted from ref. 15, with permission]) The fetal kinetocardiogram relies on tissue Doppler imaging (panel E) and identification of atrial (late diastolic wall motion or A′) and ventricular motion (isovolumic ventricular contraction spike) to determine the “AV interval”, which mirrors the P-R interval (panel F).

Glickstein and colleagues6 published the first method to assess noninvasively human fetal cardiac atrioventricular time delay. This normative study of 56 fetuses from 17 to 40 weeks’ gestation used pulsed Doppler echocardiography in the left ventricular outflow tract to record simultaneously mitral valve inflow and aortic outflow (Mitral-aorta), from which the time delay from atrial systole to ventricular systole could be inferred. This “fetal mechanical Doppler PR interval” was found to average 120 milliseconds with a standard deviation of 10 milliseconds in normal fetuses, was independent of fetal heart rate or gestational age, and was validated in 10 normal neonates by standard surface electrocardiography.

This initial work was subsequently validated in preparation for a multi-center clinical study.7 Ninety-five percent of all observations were within 25% of the mean. Furthermore, Bolnick and colleagues8 published a retrospective study of the Mitral-aorta PR interval in 96 normal fetuses in a manner identical to the Glickstein6 study. Their normal value was also 123.9 ± 10.3 milliseconds, range 90–150 milliseconds; the data showed a non-statistically significant trend toward increasing PR intervals with increasing gestational age. Finally, additional work9 confirmed that the normal Mitral-aorta PR interval was 122.4 ±10.3 milliseconds. With 336 fetuses between 16–36 weeks’ gestation, this larger study was powered to show that the PR interval increased by 0.40 milliseconds (95% confidence intervals, 0.22–0.58) per gestational week (p< 0.001), even after adjusting for fetal heart rate and fetal gender. The PR interval diminished by 1.4 milliseconds (95% confidence intervals, 0.75 – 2.0 milliseconds) for each 5 beat per minute increase in fetal heart rate (p<0.001), independently of sex or gestational age (see Table 1). These investigators have provided the most detailed data to date on the normal mechanical PR interval, and its relationship to gestational age and fetal heart rate. As can be seen, the mean PR intervals and variances agree very well among all studies.

Table 1.

Mechanical P-R intervals (in milliseconds) according to gestational age and fetal heart rate, using the Mitral-aorta Doppler method (adapted from Wojakowski 2009, with permission).

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 50%ile | 95%ile | 99%ile |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16–19 | 117.0 | 132.3 | 138.1 |

| 20–24 | 121.0 | 136.9 | 143.3 |

| 25–29 | 121.0 | 139.9 | 146.8 |

| 30–34 | 125.0 | 142.9 | 150.5 |

| 35–38 | 121.0 | 145.7 | 153.9 |

|

Fetal Heart Rate (bpm)

| |||

| 120–124 | 129.0 | 146.8 | 154.6 |

| 125–129 | 129.0 | 147.5 | 155.0 |

| 130–134 | 125.0 | 145.6 | 152.9 |

| 135–139 | 123.0 | 141.4 | 148.5 |

| 140–144 | 121.6 | 139.8 | 146.6 |

| 145–149 | 117.0 | 135.8 | 142.4 |

| 150–154 | 118.5 | 135.1 | 141.4 |

| 155–159 | 117.0 | 133.0 | 139.1 |

| 160–180 | 121.0 | 139.6 | 145.4 |

Andelfinger and colleagues10 evaluated the utility of 2 fetal cardiac Doppler techniques, the Mitral-aorta Doppler method and the unique superior caval vein a wave to aortic flow method (Superior caval vein-aorta). Their results were similar to Glickstein.6 The Mitral-aorta PR interval was in the range of 115–120 milliseconds, similar to all other studies published. There were no systematic differences between the two methods. A multivariate analysis showed only gestational age to correlate independently with PR interval as assessed by the Superior caval vein-aorta but not Mitral-aorta Doppler technique. Although the 95% confidence intervals varied somewhat with the gestational age and heart rate, the normal range of PR intervals was in the 100–135 milliseconds range, again similar to other previously published studies. Notably, variances were not determined in this study. Because the multivariate analysis showed only the Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler technique to correlate with gestational age, the investigators concluded that this was a “more suitable” technique with which to measure the fetal PR interval. In a new study that reviewed fetuses with first-degree atrioventricular block, this same group concluded that the Mitral-aorta Doppler method is “unsuitable” for prenatal screening of conduction system abnormalities, since the A wave could not be identified in almost 40% of tracings, while the Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler method could consistently identify the onset of atrial and ventricular contractions11. We note that this experience may be center- and operator-dependent, since our experience (see also references 7,12) and others’ (Dr. Julie Glickstein, personal communications) has had little if any difficulties with the Mitral-aorta Doppler technique. However, the Superior caval vein-aorta technique appears to be particularly helpful when the PR interval is so long or the fetal heart rate is so fast as to obscure the A wave.11

In a small postnatal study of 22 neonates, the Swedish group13 compared the Mitral-aorta and Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler techniques to yet a third method, the mitral A wave to mitral valve closure time (Mitral A-closure). The investigators reasoned that the Mitral-aorta and Superior caval vein-aorta techniques incorporate isovolumic contraction time into their measurements, thereby overestimating the true electrocardiographic PR interval. The study showed that Mitral-aorta Doppler technique overestimated the electrocardiographic PR interval more than Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler method, whereas the Mitral A-closure technique showed far better agreement with the electrocardiographic PR interval. Nevertheless, the coefficients of variation for all three techniques were 5–6%, and interobserver variability was acceptably low and similar for all three techniques. The investigators concluded that “all 3 techniques are useful to get indirect estimates of the PR intervals.” In our opinion, the strengths of the pulsed-wave Doppler methods include ease of use and reasonable reproducibility. However, one should acquire signals with fast sweep speeds to minimize operator measurement errors; a slow sweep speed may lead to a relatively large proportional error even with a small error in placement of the time interval measurement calipers. Fetal position may also dictate which pulsed-wave Doppler method is used, given the importance of alignment with blood flow for optimal Doppler waveform generation.14

The fetal kinetocardiogram uses principles of tissue Doppler imaging15 to determine atrioventricular conduction.16 Rein and colleagues have calculated that the sampling rate – and therefore, the time resolution – of tissue Doppler is superior to that of “traditional” pulsed-wave Doppler, and therefore, there should be more precision in time interval measurements. 16 In Rein and colleagues’ study of babies, children, and adults,16 interobserver variability was approximately 20% of the means, and correlation with surface electrocardiography was good (up to R=+0.76). However, close inspection of Rein and colleagues’ data shows that their correlation was improved by a single outlier (see their Figure 4)16 and was notably not as good as Glickstein’s results6 with Mitral-aorta Doppler technique (R=+0.99). Nii and colleagues17 prospectively compared fetal atrioventricular time intervals measured by tissue Doppler imaging, Mitral-aorta Doppler, and Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler, comparing these with fetal electrocardiography as the “gold standard”. In this large study of 196 fetal echocardiograms and 158 fetal electrocardiograms from 131 pregnant women, tissue Doppler imaging-derived intervals tracked the fetal electrocardiographic PR intervals more closely than the other Doppler techniques; also, PR increased with advancing gestational age. However, the coefficient of variation for one of the tissue Doppler imaging methods (Aa-IV) was higher than Mitral-aorta or Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler techniques. Importantly, every Doppler method tracked the fetal electrocardiographic PR interval poorly: the best R2, by the tissue Doppler imaging method, was still only +0.15, resulting in essentially a scatterplot, even if “statistically significant”. Their data are summarized in Table 2. Bland-Altman analyses showed the expected biases (e.g., Mitral-aorta method overestimating the fetal electrocardiographic PR interval), but similar clustering for all methods. Thus, despite the theoretical advantage in time resolution, our opinion is that there is no apparent justification for considering clinical superiority of the fetal kinetocardiogram technique over others in determining the fetal cardiac PR interval.5

Table 2.

A comparison of pulsed-Doppler (Mitral-aorta and Superior caval vein-aorta) and tissue Doppler imaging techniques: variances (inter- and intraobserver variabilities are 95% confidence intervals; adapted from Nii, 2006)

| Test | Standard Deviation Range | Doppler vs. Fetal Electrocardiogram | Interobserver variability | Intraobserver variability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | p | Bias | ||||

| Mitral-aorta Doppler | ||||||

| 7.3–11.1 | 0.10 | <0.002 | 18.7 ms | −18.1% to +18.7% | −19.4% to +9.5% | |

| Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler | ||||||

| 8.8–12.0 | 0.06 | <0.02 | 12.4 ms | −10.0% to +9.4% | −9.9% to +7.3% | |

| Tissue Doppler imaging | ||||||

| 7.6–14.6 | 0.15 | <0.0001 | 8.0 ms | −10.6% to +6.5% | −16.8% to +13.9% | |

Sonesson14 has also recently reviewed several techniques for diagnosing fetal AV blocks in detail, including the possible contribution of myocardial involvement in prolonging AV (or P-R) intervals determined by Doppler methods. He does not necessarily believe that the fetal kinetocardiogram method is superior to the flow Doppler techniques.

Additional methods of assessing fetal PR intervals include fetal magnetocardiography and fetal electrocardiography, although these are almost exclusively limited to research studies. In a study of anti-SSA/Ro exposed fetuses,18 Mitral-aorta PR intervals were confirmed with either fetal magnetocardiography or postnatal electrocardiography, and demonstrated to be highly feasible. Similar to other studies, the Mitral-aorta PR interval was 120.5±9.8 and 120.±8.7 milliseconds in the antibody-exposed and antibody-negative groups, respectively. Similar to Glickstein’s study6, the cutoff value for abnormally prolonged PR interval was 150 milliseconds, as determined from their data distribution, and all 4 affected fetuses with atrioventricular conduction abnormalities had PR >160 milliseconds (mean, 191.5±29.6 milliseconds). The investigators concluded that a Mitral-aorta PR interval ≥150 milliseconds is “highly suggestive” and ≥160 milliseconds “diagnostic” of fetal first-degree atrioventricular block.18 Gardiner’s group in the United Kingdom has published breakthrough work on noninvasive fetal electrocardiography, which measures fetal PR intervals electrically through specialized equipment and signal processing. Notably, obtaining a fetal electrocardiogram is not always successful, with 6–21% failure rates reported by this group.19,20 The investigators compared the PR interval by noninvasive fetal electrocardiography to the Mitral-aorta Doppler technique prospectively in 55 studies of 50 normal fetuses.20 Both tests performed well. The Mitral-aorta method correlated tightly with fetal electrocardiography, with an interobserver mean difference of -2.69 milliseconds (R=0.93) and intraobserver mean difference of +0.92 milliseconds (R=0.96). The investigators also prospectively compared fetal electrocardiography to the Mitral-aorta Doppler method from 52 consecutive anti-SSA/Ro-SSB/La exposed pregnancies in 46 women involving 54 fetuses.19 With surface electrocardiography as the standard, fetal electrocardiography appeared to be more sensitive and specific than Mitral-aorta Doppler in detecting postnatal atrioventricular block (Table 3). Sensitivity and specificity data were derived from logistical regression analysis of postnatal rhythms. The investigators speculated that the inferior test characteristics of Mitral-aorta Doppler were due to increased variances, but of course there was no way to determine prenatal test characteristics. Using z scores established in normal fetuses, fetal electrocardiography exhibited a receiver operating curve area of 0.88 with sensitivity 87.5% and specificity 95%. The Mitral-aorta Doppler technique showed good intra-and interobserver variability, although worse than fetal electrocardiography. Because higher heart rates lead to summation of the E and A waves, the Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler method may be superior to Mitral-aorta Doppler in these circumstances. Although fetal electrocardiography performed better than Mitral-aorta Doppler, the investigators concluded that both fetal electrocardiography and Mitral-aorta Doppler were valid; indeed, they preferred Mitral-aorta Doppler over Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler for ease of acquisition. It should be noted that maternal movement, fetal movement, fetal heart rate, and PR intervals in adults all show some diurnal variation,21–23 which may increase variability in the fetal PR interval. Furthermore, maternal stress may increase fetal heart rate, although probably only in specific subgroups.24 However, the timing of measurements in the studies cited in Monk and colleagues’ review24 is not provided, and we know of no data that determine how the fetal PR interval changes with diurnal cycles or maternal activity.

Table 3.

Performance of fetal electrocardiography compared to Mitral-aorta Doppler-derived mechanical PR interval determination (Gardiner 2007).

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic PR (fetal electrocardiogram) | 66.7% | 96.2% |

| Mechanical PR (Mitral-aorta Doppler) | 44.4% | 88.5% |

In summary, it is not clear that any of the currently-available techniques to determine the fetal PR interval (Mitral-aorta Doppler Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler, fetal kinetocardiogram) holds any distinct advantage over another. All appear to be useful in determining and tracking the fetal PR interval, with similar variances. The Mitral-aorta and Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler techniques are probably the most widely accessible, and we agree that facility with both these methods at least will permit the practitioner to determine the PR interval accurately under all circumstances.

CLINICAL TRIALS USING FETAL PR INTERVALS FOR EARLY DETECTION AND POSSIBLE TREATMENT OF COMPLETE HEART BLOCK

The next logical step was to determine whether PR intervals are a) abnormally prolonged in anti-SSA/Ro exposed fetuses, b) predictive of more advanced block, and c) responsive to therapeutic intervention. Answering these questions would represent a significant advance in the management of pregnancies at risk for cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Three investigative groups have attempted to address these questions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prospective studies of anti-Ro exposed pregnancies serially measuring PR intervals to monitor for progression to third-degree atrioventricular block (Bergman 2009; Friedman 2008; Rein 2009).

| Sweden | USA | Israel | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetuses (N) | 95 | 98 | 70 |

| PR technique | Mitral-aorta Doppler Superior caval vein-aorta Mitral A-closure |

Mitral-aorta Doppler | Fetal kinetocardiogram |

| Definition of 1st-degree atrioventricular block | ≥95%ile | 150 milliseconds (≥3 standard deviations) | ≥2 standard deviations |

| Normal atrioventricular conduction | 67 (71%) | 92 (94%) | 64 (91%) |

|

1st-degree atrioventricular block (fetal)

| |||

| 1st-degree atrioventricular block (N) | 24 (25%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (9%) |

| Onset of 1st-degree atrioventricular block | All < 24 weeks | 1: 20 weeks 1: 22 weeks 1: Electrocardiogram at birth (missed prenatally) |

3: 21–26 weeks 2: 32–33 weeks 1: 34 weeks |

| Treatment outcomes | 24→Normal sinus rhythm (by one month of age; no treatment?) | 2→Normal sinus rhythm (<7 days of oral dexamethasone, 4 milligrams) | 1→Normal sinus rhythm (<14 days of dexamethasone, 4 milligrams) |

|

| |||

|

Advanced (2nd- or 3rd-degree) atrioventricular block

| |||

| Advanced atrioventricular block (N) | 4 (4%) 2→3rd-degree atrioventricular block 2→2nd-degree atrioventricular block |

3 (3%) All 3rd-degree atrioventricular block |

0 (0%) |

| Serial evaluation and timing of onset in relation to 1st-degree atrioventricular block* | *1st-deg AVB@19 weeks ↓ 3rd-deg AVB@20 weeks *Normal PR@20 weeks ↓ 2nd-deg AVB@23 weeks 2→2nd-degree AVB, reverted to 1st-degree AVB (bethamethasone) ↓ |

Normal PR@ 22weeks ↓ 3rd-deg AVB@23 weeks Normal PR@19 weeks ↓ 3rd-deg AVB@21 weeks Normal PR@18 weeks 3rd-deg AVB @20 weeks |

NA |

Legend: AVB = atrioventricular block;

= For Bergman 2009 data, serial evaluation data available for selected fetuses only in their original cohort of 24 fetuses as reported in Sonesson 2004 (ref.18).

Sonesson and colleagues25 were the first to report a prospective evaluation of 24 pregnant women with anti-SSA/Ro 52 kD antibodies, comparing fetal Doppler PR interval by the Mitral-aorta or Superior caval vein-aorta methods to 284 normal controls. First-degree atrioventricular block was defined by the presence of two consecutive examinations with atrioventricular time interval measurements exceeding the 95% percentiles of their control population, which was ~130–135 milliseconds for the Mitral-aorta Doppler technique. First-degree atrioventricular block was diagnosed in one-third of exposed fetuses. However, six of these 8 cases completely normalized spontaneously. If we apply the more stringent PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation Study criterion of 150 milliseconds to define PR prolongation (see below, ref.12), only one fetus had a PR approaching 150 milliseconds at 24 weeks, which decreased to 145 milliseconds by 26 weeks; no information regarding treatment was provided. One fetus with an abnormally prolonged PR interval by the Swedish investigators’ criteria developed third-degree atrioventricular block. Specifically, the Mitral-aorta Doppler PR interval was 142 milliseconds on the first study at 19 weeks’ gestational age and progressed to third-degree atrioventricular block in 6 days. One fetus with a normal PR interval at 20 weeks (<110 milliseconds) exhibited second-degree atrioventricular block at the next study at 23 weeks’ gestation, which improved to first-degree atrioventricular block with betamethasone in one week, although the PR interval was <140 milliseconds. It is not known if this fetus progressed through first-degree atrioventricular block first sometime between 20 and 23 weeks’ gestation.

This Swedish group recently reported their larger prospective follow-up study of 87 fetuses that included this original cohort of 24 fetuses.26 The Mitral-aorta Doppler technique was confirmed to be very good at detecting abnormal atrioventricular conduction, thus providing further credence to the utility of Mitral-aorta Doppler and Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler as methods to detect and follow atrioventricular block. In all, 29% of fetuses exhibited atrioventricular conduction abnormalities; this study confirmed their earlier work that a high proportion of antibody-exposed fetuses will exhibit first-degree atrioventricular block if this is defined at >95% percentile. However, most “reverse” in the absence of therapy. With or without prenatal treatment, all 12 fetuses with first-degree atrioventricular block at birth normalized by one month of age. Notably, the Swedish group cited normal ranges from a widely-used pediatric electrocardiography textbook,26 whereas other reference ranges27,28 provide for more generous ranges of normal PR intervals in the newborn period (see also reference 29). For example, Bergman and colleagues26 state that the upper limit of normal for a 2 day old baby with a heart rate of 135 bpm is 120 milliseconds, whereas Davignon27 places the cutoff at 140 milliseconds (98% percentile). Davignon’s data in fact form the basis for the guidelines for neonatal electrocardiographic interpretation by the European Society of Cardiology.30 It has been argued by others too that Bergman’s using a lower cutoff for PR prolongation may account for a higher false-positive rate of first-degree atrioventricular block.31

Similarly, using the European Society of Cardiology’s guidelines, Gerosa and colleagues32 found a 9% incidence of first-degree atrioventricular block in SSA/anti-Ro-exposed infants 20–70 days old, as contrasted with a 4% incidence when mothers with autoimmune diseases were antibody (SSA/anti-Ro)-negative, and 0% in a control population of healthy babies born to entirely healthy mothers.

The US group led by investigators in New York12 conducted the PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation (PRIDE) prospective study, evaluating 95 women with anti-SSA/Ro antibodies in 98 pregnancies (Full disclosure: The authors of this review led the PRIDE study). A narrower definition of an abnormal fetal PR interval was intentionally set at a z score of +3 (150 milliseconds; reference 6), so that only <1% of a normal population rather than about 2.5% (z score +2) of a normal population would be considered as abnormal and justify a therapeutic intervention. In total, 6 fetuses developed a cardiac conduction abnormality: 3/74 (4%) pregnancies with no previously affected child, and 3/16 (19%) mothers with a previous child with congenital complete heart block. Three fetuses had third-degree atrioventricular block; none had a preceding abnormal PR interval, although in 2 fetuses >1 week had elapsed between evaluations. The longest preceding PR interval was 138 milliseconds, but this reverted to 120 and then 129 milliseconds prior to the diagnosis of third-degree atrioventricular block. Disturbingly, despite identification of advanced block within days after a normal PR interval was documented, reversal with therapy could not be achieved. Occasionally, tricuspid regurgitation and/or atrial echodensities preceded block, but the numbers were too small to determine a true statistical association. Two fetuses exhibited first-degree atrioventricular block at or before 22 weeks, and each reversed within 1 week following administration of daily 4 milligrams of oral dexamethasone; however, neither therapeutic response nor spontaneous reversal could be confidently ascribed. The electrocardiogram of 1 additional newborn, who was born prematurely at 32 weeks’ gestation, revealed a prolonged PR interval (first-degree AV block) persistent at 3 years despite normal intervals throughout gestation. It is notable that in this series, several fetuses had PR intervals which vacillated between 2 standard deviations above normal and normal throughout pregnancy, but all exhibited normal electrocardiograms at birth. Therefore, it does not appear that, despite a narrower definition of first-degree AV block, the methods used in the PRIDE study exhibited a lower sensitivity of detecting clinically-significant AV block.

Recently, the group in Israel33 published the results of their prospective trial using fetal kinetocardiography as the biomarker for early fetal conduction system disease. They followed 70 fetuses of 56 mothers with anti-SSA/Ro antibodies weekly from 13 weeks to delivery, and compared PR intervals to normal values generated from 109 controls. Prolonged PR intervals were defined at 2 standard deviations above the mean. Six of the exposed fetuses (8.6%) developed first-degree atrioventricular block, and all were treated with 4 milligrams of daily oral dexamethasone for the rest of the pregnancy. All PR intervals normalized permanently within 3 to 14 days. Of note, 3 cases with prolonged PR intervals did not present until 32–34 weeks’ gestation. The investigators concluded that fetal kinetocardiography can detect first-degree atrioventricular block in fetuses at risk. Because none of the fetuses developed complete heart block, the investigators argued that dexamethasone, by reversing first-degree atrioventricular block, prevents progression to more advanced heart block.

Given the potential impact of their conclusions, several comments merit consideration. The population studied may not have been equivalent to those enrolled in other studies.12,25,26 For example, the Israeli study reported no cases of advanced block, no premature babies, and no growth retardation. Three of the 6 affected cases were not found until the third trimester, whereas other studies have consistently found the greatest risk period to be earlier than 26 weeks gestation.12,25,26 Although right- and left-sided time intervals were measured, only right-sided intervals were included in the final analysis. The use of right-sided atrioventricular time intervals, even when compared with an appropriate control dataset, may be differentially affected as compared to left-sided atrioventricular time intervals, which were utilized by the Swedish and US groups. Accordingly, it is possible that the pathophysiology of first-degree atrioventricular block may not be accurately reflected in Rein’s right-sided atrioventricular time intervals. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that others have also employed right-sided AV intervals using the tissue Doppler method.34

The reasoning posited by the Israeli group – if one prevents complete heart block by treating all first-degree atrioventricular block, there will be a lower rate of third-degree atrioventricular block – is entirely valid. However, their study may not have the statistical power to conclude that the reduction in the incidence of third-degree atrioventricular block is attributable to treatment with steroids. Since an abnormal PR interval was defined at ≥2 z scores, there needs to be a statistically significant difference between 6/70 (their “incidence” of first-degree atrioventricular block) and 1-2/70 (2.5% of 70). Applying a 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test determines there is not a statistically significant difference between 6/70 and 1/70 (p=0.12), nor between 6/70 and 2/70 (p=0.27). Therefore, an alternative conclusion is that their “incidence” of first-degree atrioventricular block and their rate of “successful treatment” are due to random chance. Data from other groups12,25,26 support the possibility that the “reversion” to normal sinus rhythm may have occurred in the absence of any treatment. We acknowledge our own bias to avoid potentially unnecessary treatment with fluorinated glucocorticoid steroids since we believe they carry significant side effects for the fetus.

In a recent comparison between the PRIDE Study 12 and their own data33, Mevorach and colleagues5 conclude that if the PR interval is prolonged by Doppler mechanical PR interval, one might “consider” treatment based on the literature, but if fetal kinetocardiography or fetal electrocardiography is abnormal, this should “trigger” treatment because these latter methods are associated with fewer false positives and negatives. They then conclude that with their technique the number needed to treat is 2 to 5 fetuses. This conclusion is based on the assumptions that a) first-degree atrioventricular block is present in 8–9% of exposed fetuses, and b) 2–5% of exposed fetuses will develop complete or third-degree atrioventricular block if left untreated. However, we believe that the claim of calculating a “number needed to treat” is not valid when the precursor to disease is not yet defined rigorously, and when incidence rates vary from as little as < 5% (PRIDE study) to as high as 30% (Karolinska Institute).

Further confounding clinical decision-making is a very recent report from the Toronto group.34 165 fetuses were monitored serially, 15 of whom had either AV prolongation between 2 and 6 Z scores (N=14) or Mobitz type I (Wenkebach) 2nd-degree AV block (N=1). None of the 15 progressed to CHB. Of note, fetal AV intervals >3 Z scores may have predicted longer neonatal PR intervals. The investigators concluded that a management strategy relying on early identification and treatment of fetal AV prolongation to prevent CHB should be questioned. A natural hypothesis is that serum antibody levels would correlate with degree and/or incidence of atrioventricular block. While most studies state only the presence or absence of autoantibodies, there is some evidence that higher levels of antibodies may predict risk of atrioventricular block.35,36 In the PRIDE study, the median titer of anti-SSA/Ro antibodies in the 89 pregnancies that did not result in complete heart block was 3008, compared with a median titer of 16,128 in the 6 complete heart block pregnancies (p=0.026).12 A recent study from the Toronto group also demonstrated a significant correlation between anti-Ro levels and the risk of cardiac complications, but the positive predictive value of anti-Ro levels ≥50 U/ml (moderate or higher levels) was only 5%.37 Part of the problem is that in most cases, anti-Ro antibodies are inherently of high titer, regardless of clinical disease in either the mother or her fetus. Furthermore, high antibody titers alone are not sufficient for the development of atrioventricular block.

Despite the recent Toronto data,34 the totality of clinical and basic evidence is appealing to suggest that, as written by Mevorach,5 “there are stages to the autoantibody-induced injury”. However, it remains unclear whether “the antibody can induce lesser degrees of injury that may respond to treatment in 3 to 14 days.” A major problem with all these conclusions, of course, is that published reports have still had relatively small numbers of fetuses affected by abnormal AV conduction. These numbers would be even smaller if first-degree AV block were defined more narrowly, as in the PRIDE study. Therefore, no study has been powered to address the question of the risk of first-degree AV block. This risk remains admittedly speculative, although all parties actively engaged in the research and clinical care of these patients harbor what we believe are justifiable concerns about first-degree AV block. We concur that second-degree atrioventricular block should be treated with fluorinated steroids; and acute third-degree atrioventricular block may benefit given the possibility of rare, albeit transient, reversibility.2 Nevertheless, our interpretation of the data is that most fetal first-degree atrioventricular block in exposed fetuses is transient, although the proportion of exposed fetuses with a true pathophysiological process is as yet not known. These reservations were echoed in a recent Letter to the Editor by Guettrot-Imbert.38 The question remains: How does one decide if first-degree atrioventricular block represents true disease, and should we treat all fetuses with first-degree atrioventricular block?

CONCLUSIONS

It remains unproven whether a prolonged PR interval represents a putative “biomarker” of early disease. Clearly, autoantibody-associated fetal conduction disease can progress exceedingly rapidly,12,26 and it is therefore possible that this rapid deterioration precludes identification of progression in at least some fetuses. Alternatively, first-degree atrioventricular block may not be a necessary precursor to third-degree atrioventricular block or cardiomyopathy. Presently, we have neither a proven prophylactic approach39 nor treatment for any level of conduction abnormality. Nevertheless, there is suggestive evidence that complete (third-degree) atrioventricular block progresses through stages of incomplete atrioventricular block, including data suggesting that higher-grade atrioventricular block (second-degree or even third-degree) can revert back to lesser degrees or even normal2,4,25,26,33,40,41,42 at least transiently.

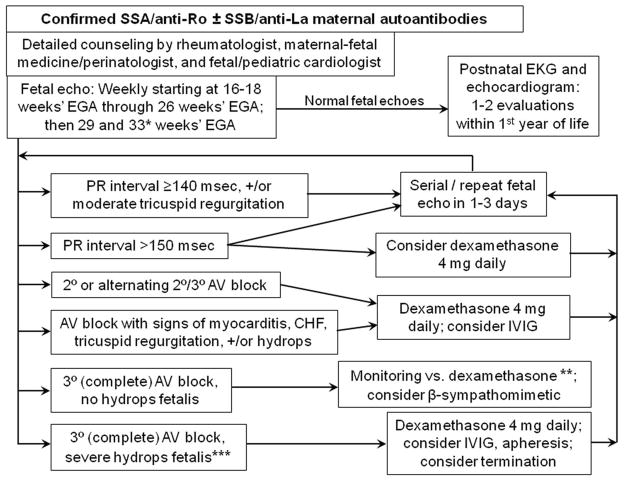

In light of the potential benefit of therapy, we and others continue to incorporate the use of this putative biomarker given the irreversibility of third-degree atrioventricular block, in conjunction with close monitoring also of the cardiac function (especially evaluating for endomyocardial fibroelastosis), tricuspid insufficiency, and atrial echodensity. One approach is to monitor exposed fetuses with a prolonged PR interval more closely: it has been our practice to see these women again in 1–3 days. While our strictly anecdotal experience corroborates that of both Sonesson and Rein, we have not yet witnessed “progression” to third-degree atrioventricular block. A suggested monitoring and management scheme is proposed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Monitoring and management scheme for autoantibody-positive mothers.

* = The original PRIDE protocol, to which we adhered in clinical practice until recently, called for biweekly monitoring from 26 through 34 weeks, in addition to the weekly scans from 16–26 weeks. Given the rarity of progression to atrioventricular block during this period, we now opt for more flexibility of monitoring during this time; as the diagram shows, we now have decreased the frequency of monitoring to twice between 26 and 34 weeks’ gestational age, once at about 29 weeks and once at about 33 weeks, if the fetus has been entirely well all along. Others have advocated close monitoring through approximately 35 weeks if there has been a previous child with CHB, which we agree is warranted.34 It should be noted that the definition of P-R interval prolongation will depend on the reference standards for the specific method used; values are shown for our laboratory using the Mitral-aorta Doppler method.

** = Third-degree (complete) atrioventricular block without fetal hydrops or other evidence of fetal compromise may be new-onset or may be established. For new-onset atrioventricular (AV) block (when sinus rhythm had been very recently observed), a trial of dexamethasone 4 mg daily is reasonable, in the slight chance that this may be reversed. β-sympathomimetic agents may also be considered in combination with dexamethasone, in efforts to increase the fetal heart rate.43 Otherwise, close (at least weekly) monitoring of fetal health, in close collaboration with maternal-fetal medicine/perinatology, is recommended.

*** = In addition to fetal hydrops, evidence of myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, endocardial fibroelastosis, and/or significant tricuspid regurgitation, might also warrant aggressive therapy in an effort to prevent almost-certain fetal demise.35

We disagree with Rein that it is time for a consensus statement on how best to measure the fetal PR interval. It is simply too premature. All current techniques to measure fetal PR intervals – Mitral-aorta Doppler, Superior caval vein-aorta Doppler, tissue Doppler imaging (fetal kinetocardiography), and possibly fetal magnetocardiography or fetal electrocardiography – are capable of measuring the same parameter similarly well. In our opinion, the Mitral-aorta Doppler technique remains the most readily available and easiest to perform by most pediatric cardiologists. In contrast to the contention that we need to find an optimal tool with which to diagnose and follow atrioventricular block, we believe the priority now is to “set the bar” and determine for each tool the true normal reference ranges for atrioventricular conduction, specifically the PR interval. Perhaps the “PR-fect solution” can be identified by a multicenter randomized trial comparing observation alone with treatment following an “abnormal PR”. This should address progression, which after all is the hard outcome we seek to avoid. Basic science efforts should continue to drive treatment approaches.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR42455-01, contract N01-AR-4-2220; PI: Buyon; and R01 AR46265; PI: Buyon).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Dr. Friedman is on the Speakers Bureau of and is a consultant for, MedImmune.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Phoon: Concept/design, data (literature) analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, approval of article, statistics.

Dr. Kim: Data (literature) analysis/interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article, statistics.

Dr. Buyon: Concept/design, data (literature) analysis/interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article, funding.

Dr. Friedman: Concept/design, data (literature) analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, approval of article.

References

- 1.Buyon JP, Clancy RM, Friedman DM. Autoimmune associated congenital heart block: integration of clinical and research clues in the management of the maternal/foetal dyad at risk. J Intern Med. 2009;265:653–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaeggi ET, Silverman ED, Yoo S-J, Kingdom J. Is immune-mediated complete fetal atrioventricular block reversible by transplacental dexamethasone therapy? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:602–605. doi: 10.1002/uog.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon PA. Congenital heart block: clinical features and therapeutic approaches. Lupus. 2007;16:642–646. doi: 10.1177/0961203307079041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruer JMPJ, Kapusta L, Stoutenbeek P, Visser GHA, Van den Berg P, Meijboom EJ. Isolated congenital complete atrioventricular block diagnosed in utero: Natural history and outcome. J Mat Fetal Neonat Med. 2008;21:469–476. doi: 10.1080/14767050802052786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mevorach D, Elchalal U, Rein AJJT. Prevention of complete heart block in children of mothers with anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La autoantibodies: detection and treatment of first-degree atrioventricular block. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:478–482. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832ed817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glickstein JS, Buyon J, Friedman D. Pulsed Doppler echocardiographic assessment of the fetal PR interval. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:236–239. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00867-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glickstein J, Buyon J, Kim M, Friedman D PRIDE investigators. The fetal Doppler mechanical PR interval: a validation study. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19:31–34. doi: 10.1159/000074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolnick AD, Borgida AF, Egan JFX, Zelop CM. Influence of gestational age and fetal heart rate on the fetal mechanical PR interval. J Mat Fetal Neonat Med. 2004;15:303–305. doi: 10.1080/14767050410001699866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wojakowski A, Izbizky G, Carcano ME, Aiello H, Marantz P, Otano L. Fetal Doppler mechanical PR interval: correlation with fetal heart rate, gestational age, and fetal sex. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:538–542. doi: 10.1002/uog.7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andelfinger G, Fouron J-C, Sonesson S-E, Proulx F. Reference values for time intervals between atrial and ventricular contractions of the fetal heart measured by two Doppler techniques. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1433–1436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mivalez Y, Raboisson MJ, Abadir S, Sarquella-Brugada G, Fournier A, Fouron JC. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of delayed atrioventricular conduction during fetal life : a reliability study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010:174.e1–174.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman DM, Kim MY, Copel JA, et al. for the PRIDE investigators. Utility of cardiac monitoring in fetuses at risk for congenital heart block: the PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation (PRIDE) prospective study. Circulation. 2008;117:485–493. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman G, Jacobsson LA, Wahren-Herlenius M, Sonesson SE. Doppler echocardiographic and electrocardiographic atrioventricular time intervals in newborn infants: evaluation of techniques for surveillance of fetuses at risk for congenital heart block. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:57–62. doi: 10.1002/uog.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonesson S-E. Diagnosing foetal atrioventricular heart blocks. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rein AJJT, O’Donnell C, Geva T, et al. Use of tissue velocity imaging in the diagnosis of fetal cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 2002;106:1827–1833. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031571.92807.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rein AJJT, O’Donnell CP, Colan SD, Marx GR. Tissue velocity Doppler assessment of atrial and ventricular electromechanical coupling and atrioventricular time intervals in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1347–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nii M, Hamilton RM, Fenwick L, Kingdom JCP, Roman KS, Jaeggi ET. Assessment of fetal atrioventricular time intervals by tissue Doppler and pulse Doppler echocardiography: normal values and correlation with fetal electrocardiography. Heart. 2006;92:1831–1837. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.093070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Bergen AH, Cuneo BF, Davis N. Prospective echocardiographic evaluation of atrioventricular conduction in fetuses with maternal Sjögren’s antibodies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1014–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardiner HM, Belmar C, Pasquini L, et al. Fetal ECG: a novel predictor of atrioventricular block in anti-Ro positive pregnancies. Heart. 2007;93:1454–1460. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.099242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasquini L, Seale AN, Belmar C, et al. PR interval: a comparison of electrical and mechanical methods in the fetus. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Vries JIP, Visser GHA, Mulder EJH, Prechtl HFR. Diurnal and other variations in fetal movement and heart rate patterns at 20–22 weeks. Early Hum Dev. 1987;15:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(87)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dilaveris PE, Färbom P, Batchvarov V, Ghuran A, Malik M. Circadian behavior of P-wave duration, P-wave area, and PR interval in healthy subjects. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2001;6:92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2001.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muro M, Shono H, Shono H, Ito Y, Uchiyama A, Iwasaka T. Analysis of the influence of diurnal variation in maternal movements on fetal heart rate acceleration. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:247–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monk C, Fifer WP, Myers MM, Sloan RP, Trien L, Hurtado A. Maternal stress responses and anxiety during pregnancy: effects on fetal heart rate. Dev Psychobiol. 2000;36:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonesson S-E, Salomonsson S, Jacobsson L-A, Bremme K, Wahren-Herlenius M. Signs of first-degree heart block occur in one-third of fetuses of pregnant women with anti-SSA/Ro 52 kd antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1253–1261. doi: 10.1002/art.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergman G, Wahren-Herlenius M, Sonesson SE. Diagnostic precision of Doppler flow echocardiography in fetuses at risk for atrioventricular block. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/uog.7532. Dec 22, epub ahead of print. downloaded January 22, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davignon A, Rautaharju P, Boiselle E, Soumis F, Mégélas M, Choquette A. Normal ECG standards for infants and children. Pediatr Cardiol. 1980;1:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rijnbeek PR, Witsenburg M, Schrama E, Hess J, Kors JA. New normal limits for the paediatric electrocardiogram. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:702–711. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buyon JP, Askanase AD, Kim MY, Copel JA, Friedman DM. Identifying an early marker for congenital heart block: when is a long PR interval too long? Comment on the article by Sonesson et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1341–1342. doi: 10.1002/art.20971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz PJ, Garson A, Jr, Paul T, et al. Guidelines for the interpretation of the neonatal electrocardiogram. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1329–1344. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2002.3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rein AJ, Mevorach D, Perles Z, Shovali A, Elchalal U. Fetal first-degree heart block, or where to set the confidence limit: comment on the article by Sonesson et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:366–368. doi: 10.1002/art.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerosa M, Cimaz R, Stramba-Badiale M, et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in infants born from mothers with autoimmune diseases – a multicentre prospective study. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1285–1289. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rein AJJT, Mevorach D, Perles Z, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of atrioventricular block in the fetus exposed to maternal anti-SSA/Ro-SSB/La antibodies: a prospective, observational, fetal kinetocardiogram based study. Circulation. 2009;119:1867–1872. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.773143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaeggi ET, Silverman ED, Laskin C, Kingdom J, Golding F, Weber R. Prolongation of the atrioventricular conduction in fetuses exposed to maternal anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies did not predict progressive heart block. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buyon JP, Clancy RM, Friedman DM. Cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus erythematosus: guidelines to management, integrating clues from the bench and bedside. Nature Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2009;5:139–148. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buyon JP, Friedman DM. Neonatal lupus. In: Lahita RG, editor. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. 5. Academic Press, Elsevier; New York: 2011. p. 541ff. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaeggi E, Laskin C, Hamilton R, Kingdom J, Silverman E. The importance of the level of maternal anti-Ro/SSA antibodies as a prognostic marker of the development of cardiac neonatal lupus erythematosus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2778–2784. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guettrot-Imbert G, Costedoat-Chalmeau N, Amoura Z. Letter regarding article: “Early diagnosis and treatment of atrioventricular block in the fetus exposed to maternal anti-SSA/Ro-SSB/La antibodies”. Circulation. 2009;120:e167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.885418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman DM, Llanos C, Izmirly PM, et al. Evaluation of fetuses in a study of intravenous immunoglobulin as preventive therapy for congenital heart block: Results of a multicenter, prospective, open-label clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1138–1146. doi: 10.1002/art.27308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleeb S, Copel J, Friedman D, Buyon JP. Comparison of treatment with fluorinated glucocorticoids to the natural history of autoantibody-associated congenital heart block. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2335–2345. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2335::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Askanase AD, Friedman DM, Copel J, et al. Spectrum and progression of conduction abnormalities in infants born to mothers with anti-SSA/Ro – SSB/La antibodies. Lupus. 2002;11:145–151. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu173oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedman DM, Kim MY, Copel JA, Llanos C, Davis C, Buyon JP. Prospective evaluation of fetuses with autoimmune-associated congenital heart block followed in the PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation (PRIDE) Study. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1102–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hutter D, Silverman ED, Jaeggi ET. The benefits of transplacental treatment of isolated congenital complete heart block associated with maternal anti-Ro/SSA antibodies: a review. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]