Abstract

Major professional organizations have called for psychosocial risk screening to identify specific psychosocial needs of children with cancer and their families and facilitate the delivery of appropriate evidence-based care to address these concerns. However, systematic screening of risk factors at diagnosis is rare in pediatric oncology practice. Subsequent to a brief summary of psychosocial risks in pediatric cancer and the rationale for screening, this review identified three screening models and two screening approaches (Distress Thermometer [DT], Psychosocial Assessment Tool [PAT]), among many more papers calling for screening. Implications of broadly implemented screening for all patients across treatment settings are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

As pediatric patients and their parents learn of a cancer diagnosis and embark on an often lengthy and intensive course of treatment, they are at increased risk for new or exacerbated psychosocial difficulties [1,2]. The International Psycho-oncology Society terms distress as the "sixth vital sign" [3] and major professional organizations [5, 6, 7] call for standards of care that include psychosocial screening. Psychosocial screening is brief, non-stigmatizing and not burdensome, identifies families with current difficulties or those at-risk for later problems, efficiently directs them to available evidence-based treatments [8,9] and ideally can reduce risk and improve functioning.

Screening is the brief first step in a logical process of identifying risks (and competencies), determining need for further evaluation, and developing an appropriate treatment plan. Based on a public health sieve and sort approach to identifying those at risk for adverse outcomes, a positive screen indicates the need for a more comprehensive examination [10]. In the pediatric oncology setting, screening is consistent with secondary prevention. That is, all children diagnosed with cancer and their families may be at higher risk for difficulties related to this significant stressor. Screening provides a means to determine those at highest risk and in those most in need of additional resources and interventions to strengths. Because the population is accessible and the risk of missing important psychosocial information is significant, the cost being failure to treat problems that may escalate over time and potentially complicate medical care, screening is important and practical. Rather than relying on less systematic provider-determined referral patterns, this type of screening helps assure equal access to psychological services [11] by reducing the potential for disparities in care and facilitating more cost-effective and appropriate allocation of scarce resources [12].

There is strong evidence for the adaptive competence of children and families in pediatric oncology. Distress shortly after learning the diagnosis and initiating treatment is normal [20] and not a marker of psychopathology. Over time most families return to their baseline level of functioning [21,22]. The subset of patients and families in which distress remains high or escalates is of particular concern [23,24]. These patients and families are in greatest need of available evidence-based interventions to reduce distress and augment adjustment and effective screening should be capable of identifying these families.

The literature on child and family adjustment to pediatric cancer supports the importance of a broad-based, family-centered approach to screening. While depression is the most common focus of screening in adults with cancer [13], depression is less salient in pediatric oncology, especially for the diagnosed child [14]. Indeed, parents are often at greater risk for psychological effects than their children with cancer [15]. Parental wellbeing, child developmental factors, and prior experiences that may amplify stress reactions [16] are closely associated with child adjustment [17,18,19]. Therefore, in addition to evaluating the child’s status, understanding the wellbeing of parents and the broader family is essential.

There is a broad array of risk factors and vulnerabilities that are associated with intense and persistent distress for families of children with cancer. They include factors related to the child (age, temperament, behavior [25,26]), the illness and treatment (diagnosis, type/intensity of treatment, days in hospital [27]); family structure (number of parents [25,28]), financial concerns (costs of care [29–32]), adjustment of family members (parental/sibling adjustment [15,33]), family functioning (cohesiveness, communication [34]), social support (connectedness vs. isolation [35–38]), and parental beliefs about child’s treatment and its impact on the family [39]. School factors (continuity in education, learning problems [40]), and aspects of the broader community and culture (language, culture and socioeconomic status), are also considerations [41]. Assessment of risk factors is critical to the delivery of psychosocial care matched to the needs of children and families across the course of treatment and reduces the likelihood of poorer child and family psychosocial outcomes. Because these psychosocial risk factors may influence families’ connections with medical providers, acceptance of treatment approaches and adherence to treatment, early and targeted intervention may improve medical outcomes.

Given the broad range of well-established risks and their potential gravity and impact on treatment outcomes, systematic screening of psychosocial risk is a critical initial step in clinical practice. However, a recent survey of 127 Children’s Oncology Group (COG) institutions indicates that evidence-based psychosocial assessments and interventions were used infrequently and/or inconsistently [42]. In 62.5% of these institutions, more than half of the families are offered these services. When asked specifically what approaches are used for assessment, only 9.3% indicated a specific standardized approach. Given that the majority of hospitals that treat children with cancer have either integrated psychosocial professionals (part of the oncology team) or consultants (as needed), informal or highly specialized assessments may occur, although not in a standardized or systematic universal manner. This review was conducted in order to systematically identify 1) conceptual models to guide screening and 2) specific approaches for psychosocial risk screening during pediatric cancer treatment.

METHODS

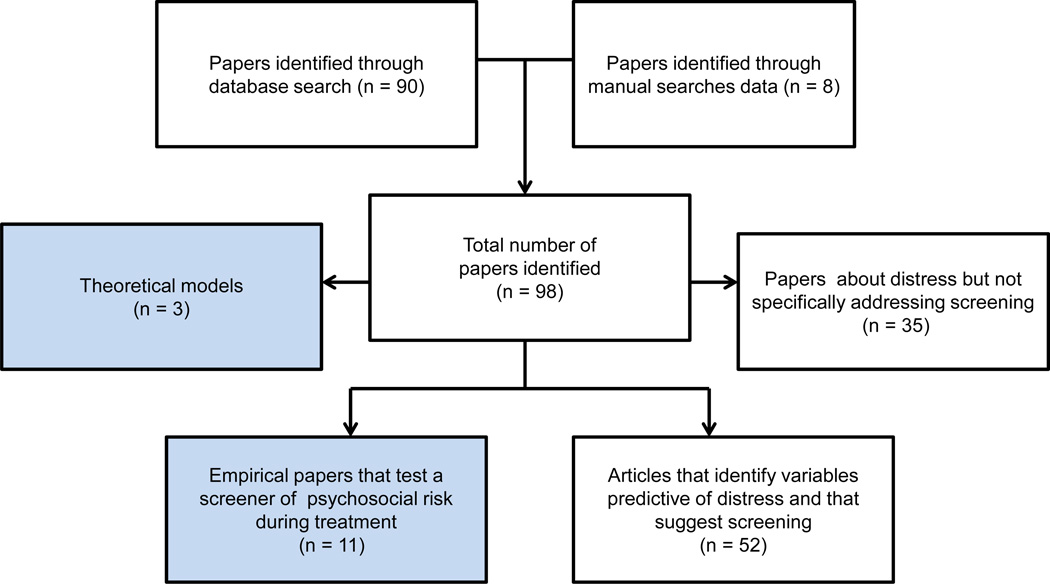

A literature search of published papers since 1990 was conducted using PsycInfo, Cinahl, PubMed, and Health and Psychosocial Instruments Database. Search terms were "pediatric oncology" or "pediatric cancer" or "childhood cancer" AND (screen* or tool* or assess* or classify* or categorize or evaluate or “psychosocial risk” or “psychosocial need” or “psychosocial care” or “at-risk” or “level of risk” or “identify risk” or distress or parents) and NOT survivor*. Reference sections of papers were reviewed to identify other papers. Articles were classified independently by two authors (MB, AK). A third author (LB) reviewed the classification, and the three reached consensus on the organization of papers in the review.

RESULTS

The search identified 98 papers (Figure 1). Across these papers, three theoretical and/or clinical models to guide screening were identified. Descriptive papers that reported on distress of patients or family members, but without mention of screening were excluded (n = 35).1 The remaining papers were categorized as: a) Empirical articles that explicitly address psychosocial risk screening during pediatric cancer treatment (n = 11; Table 1); and b) Articles that identify variables predictive of distress and note the need for screening based on their findings (n = 52).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection and review.

Models for risk screening

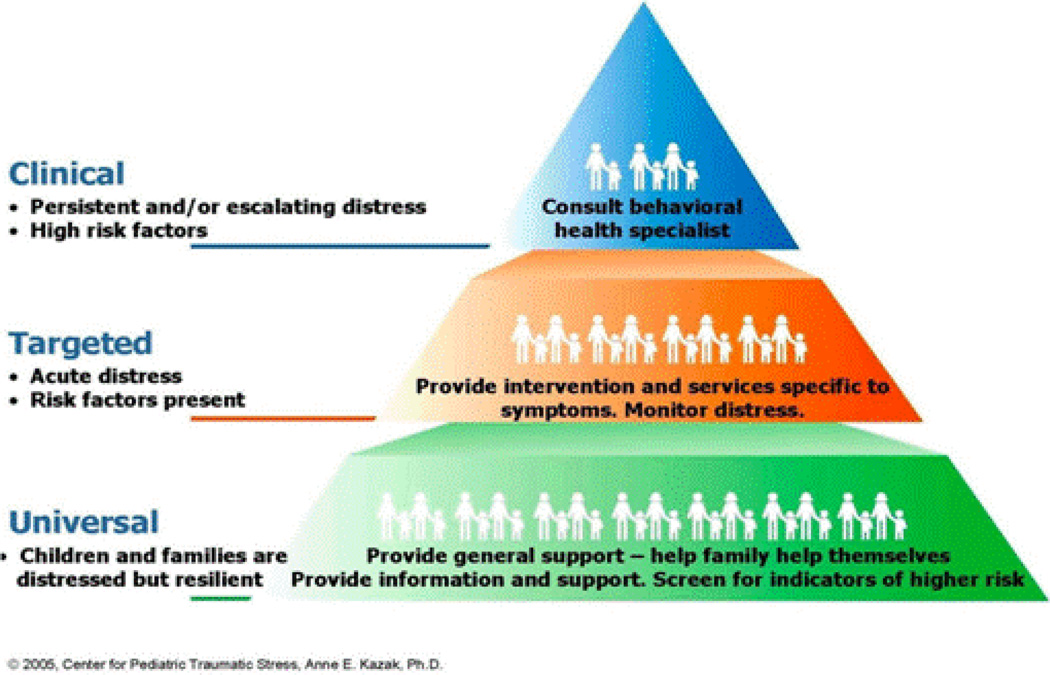

One conceptual model for psychosocial screening in pediatric cancer is the Pediatric Preventative Psychosocial Health Model (Figure 2, PPPHM [43]), the a priori theoretical basis of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool [PAT] (see below). Using a public health framework, the PPPHM was informed by the prior empirical literature and conceptualized to distinguish among levels of risk and formulated matched treatment strategies. Following the PPPHM, the majority of families of children with cancer experience temporary distress but have minimal risk factors and sufficient resources that help them cope successfully and adapt to their child’s illness (Universal Level). The appropriate intervention approach for these families is basic psychosocial care (e.g., education, resources, assistance with treatment demands). A smaller group of families (Targeted Level) have some identified areas of risk and moderate resources, and are likely to benefit from targeted interventions to reduce symptoms (e.g.,, pain, anxiety) and promote more adaptive adjustment across the family system. At the top of the pyramid are families with more severe problems, many risk factors, pre-existing psychological problems (e.g.,, child or parent anxiety, child behavior problems, parent substance use), and few resources (Clinical Level) that generally warrant multi-pronged intensive evidence-based treatments. Factors contributing to classification at a level of risk can change over time, resulting in potential changes in PPPHM risk levels and interventions. Screener findings mapped to the PPPHM can guide specific evidence-based interventions for children and families.

Figure 2.

Pediatric Preventative Psychosocial Health Model (PPPHM). Studies of the PAT support classification of families into risk levels consistent with the PPPHM: Universal (55–72%), Targeted (24–32%), and Clinical (4–13%) [55,56,58].

A second model underlying screening in pediatric cancer in the Philippines is derived from family medicine. The Family APGAR approach [44] focuses on dimensions of family functioning such as adaptability, partnership, growth, affection and resolve. SCREEM represents areas of family functioning - Social, Cultural, Religious, Economic, Educational, and Medical [45]. A SCREEM-based screener was used to evaluate the family’s ability to cope with a child’s cancer diagnosis. A third (untested) model from adolescent medicine was derived from the developmental and clinical literature to focus on issues relevant to adolescents and young adults. The HEADDS framework – Home, Education, Employment, Eating, Exercise; Activities and peers; Drugs; Sexuality, Suicide and depression, and Safety – provides queries to adolescents for each area and considers any “positive” response as indicative of risk [46]. The HEADDS approach is advocated as a means of engaging AYAs with cancer in preventative healthcare throughout their treatment course.

Theoretically-derived and empirically-supported tools

Two empirical approaches specific to psychosocial screening in pediatric cancer were identified - the Distress Thermometer (DT) and the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) - each put forward by two separate investigative teams. Two additional screening approaches are reported in the literature (used in one study each).

Distress Thermometer (DT). Modeled after the widely recognized and utilized pain scales, the DT [6,47–49] provides a very brief unidimensional rating of distress, which has been used in two pediatric studies. Patel and colleagues [50] adapted the DT for children at different age levels by including a rating scale with faces for 2–4 year olds and with developmentally appropriate words for children 5–7 years old. Parents completed the standard DT [6] as well as maternal report data. They used scores of 5 and 8 as indicative of moderate and severe distress, respectively. A brief problem list was also included. DT ratings were obtained from patients and parents at diagnosis and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months later. Ratings on the DT and other study measures were used to classify patient distress as mild, moderate or severe. Small to medium size correlations between DT ratings and measures of child depression and quality of life were reported, indicating that the DT may be useful as a marker of general distress in pediatric cancer. Warner and colleagues [51] used the DT to screen for parent distress to determine eligibility for a behavioral intervention during childhood cancer treatment and reported decreases in distress associated in the feasibility trial. Suggested future research with the DT includes examination of its sensitivity and specificity.

The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT). The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) [52–59] is a brief parent report screener guided by social ecological theory [60] and research documenting key areas of functioning associated with adjustment. The PAT identifies specific risks and maps onto the PPPHM tri-level classification of families into Universal, Targeted or Clinical risk levels. PAT has seven theoretically and clinically meaningful subscales (Structure/Resources, Family Problems, Social Support, Stress Reactions, Family Beliefs, Child Problems, and Sibling Problems). PAT has strong psychometric properties, including excellent sensitivity and specificity for predicting clinically significant outcomes related to child behavior and parent acute distress [57] and psychosocial risk classification is generally stable across the first four months of cancer treatment [56]. The distribution of families scoring in the Universal, Targeted, and Clinical levels based upon PAT scores is consistent across studies and as hypothesized by the PPPHM. In a feasibility study, most families were capable of completing the PAT within 48 hours of diagnosis, and in nearly all cases, PAT scores and interpretations were communicated to the treatment team within 48 hours of completion [54]. Compared to families who received non-standardized assessment as usual, families screened with PAT received more psychosocial services and families at higher levels of risk received more intensive services [55]. Over 1600 PATs have been given in the US, most (80%) for clinical care (20% research) [61]. The PAT has been translated into other languages and adapted for nononcologic groups [62,63].

Other screening approaches

The SCREEM Family Resources Questionnaire was found to have four factors (Social-cultural-religious; economic; educational; medical) based on a study of 90 families of children with cancer in the Philippines and validated against a Family APGAR [44]. The SCREEM was reported to be a helpful measure for establishing psychosocial needs, with over half of the sample having elevated scores and evidence of psychosocial need [45]. For screening focused on the patient, The Beck Youth Inventory II [64] a standardized measure of depression and anxiety has been used in one study as a screening measure for adolescents on treatment and was found to be a feasible approach, although patient-reported rates of anxiety and depression were low [65].

Articles that identify variables predictive of distress and that suggest screening

A large number of papers suggested that psychosocial screening was important, based on the interpretation of data reported in these studies. This multidisciplinary literature consists primarily of self-report (parent-report) measures, some well-validated and some newly developed, that represent a broad range of constructs and outcomes (e.g.,, personality characteristics, depression, anxiety, uncertainty, parenting, family functioning, etc.) as well as qualitative approaches. A thorough analysis of these papers is not reported here in order to maintain the focus of this review on psychosocial risk screening approaches. However, it is important to note that this literature illustrates the breadth of factors relevant to psychosocial risk assessment in families of children with cancer and provides an evidence base for psychosocial distress in these children and their families. It does not, however, directly guide screening approaches.

DISCUSSION

This review identified three frameworks to guide pediatric psychosocial screening in pediatric cancer and two screening approaches that have promise for integration in clinical care, specifically the DT and the PAT. Other approaches – one for families, the SCREEM, and one for individual patients, the Beck Youth Inventory II, are reported in one paper each and warrant further investigation. Numerous papers highlight the importance of screening for a range of child and family outcomes but few potential candidate screeners were identified. Given that systematic universal screening is rarely implemented in pediatric oncology care [42], the field is primed for refinement of screening approaches as well as investigations of outcomes associated with implementation of screening and subsequent treatments for identified risks. Screening is a viable alternative to more time-intensive evaluations, good practice and facilitates the delivery of optimal care for children with cancer. Without downplaying the financial limitations at institutions worldwide and challenges associated with assuring financially viable psychosocial care, screening is important and may not be as onerous to implement as widely believed.

Screeners are available and screening is acceptable to families. The DT follows from the adult screening literature and is very brief and easy to use. It measures distress as a singular construct and therefore may not provide sufficient specificity to guide psychosocial care [66]. The PAT reflects a broader literature on psychosocial risk in children and families and is based on a theoretical model (the PPPHM). All the screening studies identified in this review had very high rates of participation, demonstrating that screening is feasible within days of diagnosis. Screening is also consistent with patient-reported outcomes [67]. The importance of obtaining patient and family data is illustrated by the divergent perspectives on distress and psychosocial risk across patient, parents, and staff. Data from the DT and PAT provides evidence of variability across reporters [50,68], consistent with a broader literature indicating that both under-detection and over-detection (false positives) are common when screening is based on only clinician report [69], further highlighting the need for information obtained directly from families and exploring hybrid models using patient, parent and staff report.

Screening itself is brief and requires few additional resources. With evolving use of technology and the potential integration of screening tools in electronic medical records, identifying families and asking that they complete a screener can be a brief first step in a broader assessment protocol conducted in multidisciplinary settings. Screening is less costly than a more comprehensive evaluation. If used to accurately match needs with intervention, it may also be less costly than applying interventions for families who may not need them. Screening can be routinized as part of the initial social work or nursing intake processes. For example, PAT has been successfully distributed and collected by nursing staff. Screening measures can be completed by parents very quickly, and scoring and communication of results can be automated as in the adult screening literature [70]. The process of screening likely requires the support of a staff member to assure accurate identification of patients, access to the screener and scoring/communication of results.

Like any change in practice, consistent and persistent efforts to assure the success of screening are necessary. It is difficult to ask overworked clinicians to add screening to their responsibilities. And, some resistance to screening may come from those who might be most expected to embrace screening procedures. That is, psychosocial staff may worry that they will be “replaced” by a screener or be skeptical of whether the screener can provide additional, useful information. Working with staff to establish how screening can augment existing practice and help focus care where it is most needed is an ongoing process. Similarly, champions of screening who have authority and credibility, must work with hospital leaders to assess how screening may contribute to patient care and safety, efficiency and cost offsets.

Screening requires additional assessment in order to fully understand risks reported and to formulate actions to address identified problems. However, services are available across most pediatric hospitals for the common types of problems identified through psychosocial screening. Social workers can facilitate access to local advocacy and support organizations and national foundations to assist families facing financial difficulties. Screening can help streamline the process by which concrete economic needs are recognized and addressed promptly. Also, there are evidence-based interventions available for many of the problems identified in screening [9,71]. For example, for patients with pre-existing behavioral concerns, behavioral and/or cognitive behavioral treatments can be used to enhance adherence to treatment. Family problems (e.g., substance use, conflict) can similarly be identified and relevant treatments, both internal and external to the hospital, can be identified. Although not all hospitals will have easy access to a full range of evidence-based interventions, referrals to community providers can be facilitated. The COG study [42] highlights the importance of education for multidisciplinary team members about the availability of effective treatments.

Although screening at diagnosis is the usual focus, the optimal time(s) for screening are not yet known. As mentioned above, psychosocial risk classification, based on the PAT, was quite stable across 4 months [56,58]. Families classified at higher levels of psychosocial risk at diagnosis had more distress, more family problems, and greater psychosocial service use 4 months into treatment [56]. Therefore, it could be argued that intervention can be provided closer to diagnosis and earlier in treatment in a more preventative manner, or later, in a remediation framework. Earlier (preventative) is likely better and less costly in the long run. However, repeated screening may be necessary to identify cases where distress escalates over time or has a delayed onset. Targeting specific transitions in care (i.e., relapse, end of treatment) for re-screening may be particularly important.

The extent to which screening prompts care matched to the needs of the patient and family is an emerging area of research. There is evidence from the PAT that screened families received more psychosocial services and that the services received corresponded to risk [55]. Patel and colleagues [50] intended screening as an intervention, but assessment of intervention effects was complicated because families could access available psychosocial services irrespective of risk. Screening initiates a process which needs to be supported and well thought out. Ethical and clinical concerns may arise if psychosocial problems are identified through screening that cannot be addressed; therefore, plans must be in place for using resources appropriately and flexibly to respond to screening results. The majority of families in our studies agree to make their personal information available to the treatment team and there have been no adverse events in our PAT studies. With electronic medical records, plans for determining what information is communicated to which providers and for safeguarding patient information must be developed.

Future research is needed linking psychosocial risk screening to important clinical processes and outcomes. It is important, for example, to understand how risk level, identified through screening, relates to adherence to treatment, provider-family communication, family functioning and satisfaction, and what factors may drive changes in adjustment over time. More information about how psychosocial risk may relate to or change with variations in disease risk or treatment intensity would also be helpful. Finally, identifying relevant outcomes for screening and assuring linkages with integrated care are important next steps.

In conclusion, the results of this review indicate the presence of models to guide screening and a robust database of studies identifying variables associated with patient and family risk and resilience in pediatric cancer. Two brief screening tools have been tested and could be integrated into clinical care. In order to do so, a modest investment of support is necessary to assure identification of newly diagnosed families, timely completion of the screeners, and communication of results to the treatment team. The results of family reported psychosocial screening data, once integrated with other clinical data, could augment the efficient delivery of comprehensive patient and family centered care. Because psychosocial risks can contribute to health disparities, systematic universal screening of psychosocial risks may address health disparities by identifying potential factors that might impact cancer treatment and by facilitating equal access to psychosocial services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this review was supported, in part, by grants to the first author (CA106928, SM058139).

Footnotes

In order to be comprehensive we included "assessment" as a search term. This identified some papers that provided outcomes based on more comprehensive assessment of patients or families or that described treatment models but did not focus on brief screening approaches. We recognize that other papers addressing psychosocial outcomes were not identified due to the terms used in this search. This broader literature informs this field broadly but is not addressed in this more focused review.

References

- 1.Dolgin MJ, Phipps S, Fairclough DL, et al. Trajectories of adjustment in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A natural history investigation. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(7):771–782. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vannatta K, Salley C, Gerhardt C. Pediatric oncology: Progress and future challenges. In: Roberts M, Steele R, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. New York: Guilford; 2010. pp. 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Psycho-oncology Society web site. [Accessed November 15, 2011]; http://www.ipos-society.org.

- 4.Adler NE, Page A. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. p. 339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. National action plan for childhood cancer: Report of the national summit meetings on childhood cancer. [Accessed November 15, 2011]; doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.377. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/childhoodcanceractionplanpdf.pdf, Published 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress management clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003;1:344–374. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers web site. [Accessed November 15, 2011]; http://www.aposw.org/html/standards.php.

- 8.Sahler OJ, Fairclough D, Phipps S, et al. Using problem solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spirito A, Kazak AE. Effective and emerging treatments in pediatric psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raffle AE, Muir Gray JA. Screening: Evidence and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vodermaier A, Linden WSC. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: A systematic review of assessment instruments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(21):1464–1488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang PS, Patrick A, Avorn J, et al. The costs and benefits of enhanced depression care to employers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(12):1345–1353. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meijer A, Roseman M, Milette K, et al. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cancer: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phipps S. Adaptive style in children with cancer: Implications for a positive psychology approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1055–1066. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pai ALH, Greenley RN, Lewandowski A, et al. A meta-analytic review of the influence of pediatric cancer on parent and family functioning. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(3):407–415. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz B, Abrams A. Psychiatric aspects of pediatric cancer. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(4):1003–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jantien Vrijmoet-Wiersma CM, van Klink JMM, Kolk AM, et al. Assessment of parental psychological stress in pediatric cancer: A review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(7):694–706. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson KE, Gerhardt CA, Vannatta K, Noll RB. Parent and family factors associated with child adjustment to pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;32(4):400–410. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klassen A, Raina P, Reineking S, et al. Developing a literature base to understand the caregiving experience of parents of children with cancer: A systematic review of factors related to parental health and well-being. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(7):807–818. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patiño-Fernández AM, Pai ALH, Alderfer M, et al. Acute stress in parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2):289–292. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alderfer M, Kazak A. Familial issues when a child is on treatment for cancer. In: Brown RT, editor. Comprehensive handbook of childhood cancer and sickle cell disease: A biopsychosocial approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak AE, Kassam-Adams N, Schneider S, et al. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(4):343–355. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Best M, Streisand R, Catania L, et al. Parental distress during pediatric leukemia and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) after treatment ends. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(5):299–307. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuber ML, Kazak AE, Meeske K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 1997;100(6):958–964. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpentier MY, Mullins LL, Elkin TD, et al. Predictors of health-harming and health-protective behaviors in adolescents with cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2008;51:525–530. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller KS, Vannatta K, Compas BE, et al. The role of coping and temperament in the adjustment of children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(10):1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues N, Patterson JM. Impact of severity of a child’s chronic condition on the functioning of two-parent families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:417–426. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown R, Wiener L, Kupst MJ, et al. Single parenting and children with chronic illness: An understudied phenomena. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:408–421. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom BS, Knorr RS, Evans ED. The epidemiology of disease expenses: The costs of caring for children with cancer. JAMA. 1985;253:2393–2397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heath JA, Lintuuran RM, Rigguto G, et al. Childhood cancer: Its impact and financial costs for Australian families. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;23:439–448. doi: 10.1080/08880010600692526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miedema B, Easley J, Fortin P, et al. The economic impact on families when a child is diagnosed with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2008;15(4):173–178. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, et al. The cost of childhood cancer from the family's perspective: A critical review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(5):707–717. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(8):789–805. doi: 10.1002/pon.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazak AE, Rourke M, Navsaria N. Families and other systems in pediatric psychology. In: Roberts M, Steele M, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. New York: Guilford; 2010. pp. 656–671. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alderfer MA, Hodges J. Supporting siblings of children with cancer: A need for family-school partnerships. School Ment Health. 2010;2:72–81. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speechley K, Noh S. Surviving childhood cancer, social support and parents’ psychological adjustment. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:15–31. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wijnberg-Williams BJ, Kamps WA, Klip EC, et al. Psychological distress and the impact of social support on fathers and mothers of pediatric cancer patients: Long-term prospective results. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:785–792. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Jaspers JP, Kamps WA, et al. Psychological adaptation and social support of parents of pediatric cancer patients: A prospective longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:225–235. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.4.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazak AE, McClure KS, Alderfer MA, et al. Cancer-related parental beliefs: The Family Illness Beliefs Inventory (FIBI) J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:531–542. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Power TJ, DuPaul GJ, Shapiro ES, Kazak AE. Promoting children’s health: Integrating school, family and community. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen E, Paterson LQ. Neighborhood, family and subjective socioeconomic status: How do they relate to adolescent health? Health Psychol. 2006;25:704–714. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selove R, Kroll T, Coppes M, Cheng Y. Psychosocial services in the first 30 days after diagnosis: Results of a web-based survey of Children’s Oncology Group (COG) member institutions. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pbc.23235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazak AE. Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM): Research, practice and collaboration in pediatric family systems medicine. Fam Syst Health. 2006;24:381–395. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smilkstein G. The Family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. 1978;6:1231–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panganiban-Corales AT, Medina MF. Family Resources Study : Part 1: Family resources, family function and caregiver strain in childhood cancer. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2011;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1447-056X-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeo M, Sawyer S. Psychosocial assessment for adolescents and young adults with cancer. CancerForum. 2009;33(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychological distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103:1494–1502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the distress thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15:604–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel SK, Mullins W, Turk A, et al. Distress screening, rater agreement, and services in pediatric oncology. Psychooncology. 2011;20(12):1324–1333. doi: 10.1002/pon.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warner CM, Ludwig K, Sweeney C, et al. Treating persistent distress and anxieiety in parents of children with cancer: An intitial feasibility trial. Journal of Pediatric oncology Nursing. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2011;28(4):224–230. doi: 10.1177/1043454211408105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazak AE, Prusak A, McSherry M, et al. The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT): Development of a brief screening instrument for identifying high risk families in pediatric oncology. Fam Syst Health. 2001;19:303–317. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kazak AE, Cant MC, Jensen MM, et al. Identifying psychosocial risk indicative of subsequent resource utilization in families of newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3220–3225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alderfer MA, Mougianis I, Barakat LP, et al. Family psychosocial risk, distress and service utilization in pediatric cancer: Predictive validity of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Cancer. 2009;115:4339–4349. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pai AL, Patiño-Fernández AM, McSherry M, et al. The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0): Psychometric properties of a screener for psychosocial distress in families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:50–62. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Ditaranto S, et al. Screening for psychosocial risk at cancer diagnosis: The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:289–294. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31820c3b52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Hwang WT, et al. Association of psychosocial risk screening in pediatric cancer with psychosocial services provided. Psychooncology. 2011;20:715–723. doi: 10.1002/pon.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy MC, Clarke NE, Vance A, et al. Meauring psychosocial risk in families caring for a child with cancer: The psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:78–83. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrera M, Hancock K, Cataudella D, Punnett A, Bartels U, Nathan P, Shama W, Brownstone D, DeSouza C, Johnston D, Cassidy M, Silva M, Jensen P, Zelcer S, Atenafu E, Greenberg C. Cultural adaptation and face validity of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0) in childhood cancer. Presented at: Annual Symposium of the Pediatric Oncology Group of Ontario; November 2010; Toronto, ON. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kazak AE. Families of chronically ill children: A systems and social ecological model of adaptation and challenge. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:25–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kazak AE, Biros DE, Schneider S. Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Users Manual. Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pai AL, Tackett A, Ittenbach RF, et al. Psychosocial Assessment Tool 2.0_General: Validity of a psychosocial risk screener in a pediatric kidney transplant sample. Pediatr Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sampilo M, Lassen S, Belmont J, et al. Development and validation of a psychosocial screening tool to identify high-risk families in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: The PAT-NICU. Poster presented at: National Child Health Psychology Conference; April 2011; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beck J, Beck A, Jolly J, et al. Beck youth inventories for children and adolescents. San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kersun LS, Rourke MT, Mickley M, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety in adolescent cancer patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:835–839. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181b8704c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jacobsen PB. Screening for psychological distress in cancer patients: Challenges and opportunities. J Clin Oncol. 2007;29:4526–4527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clauser SB, Ganz PA, Lipscomb J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: Evaluating and enhancing the payoff to decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2007;32:5049–5050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patino-Fernandez AM, Pai A, Alderfer M, et al. Psychosocial risk: Perspectives of mothers, physicians and nurses. Presented at: Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; September 2006; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell AJ, Vahabzadeh A, Magruder K. Screening for distress and depression in cancer settings: 10 lessons from 40 years of primary-care research. Psychooncology. 2011;20:572–584. doi: 10.1002/pon.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loscalzo M, Clark K, Dillehunt J, et al. SupportScreen: A model for improving patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc. 2010:8496–8504. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wiener LS, Pao M, Kazak AE, et al., editors. Quick reference for pediatric oncology clinicians: The psychiatric and psychological dimensions of pediatric cancer symptom management. Virginia: IPOS Press; 2009. p. 354. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.