Abstract

Background

Administration of the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, and positive allosteric modulator (PAM), GS39783, has been repeatedly reported to suppress multiple alcohol-related behaviors, including operant oral alcohol self-administration, in rats. The present study was designed to compare the effect of baclofen and GS39783 on alcohol self-administration in three lines of selectively bred, alcohol-preferring rats: Indiana alcohol-preferring (P), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP), and Alko Alcohol (AA).

Methods

Rats of each line were initially trained to respond on a lever, on a fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4) schedule of reinforcement, to orally self-administer alcohol (15%, v/v) in daily 30-min sessions. Once responding reached stable levels, rats were exposed to a sequence of experiments testing baclofen (0, 1, 1.7, and 3 mg/kg; i.p.) and GS39783 (0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg; i.g.) on FR4 and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement. Finally, to assess the specificity of baclofen and GS39783 action, rats were slightly food-deprived and trained to lever-respond for food pellets.

Results

The rank of order of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol was: P>sP>AA rats. Under both FR and PR schedules of reinforcement, the rank of order of potency and efficacy of baclofen and GS39783 in suppressing alcohol self-administration was: P>sP>AA rats. Only the highest dose of baclofen reduced lever-responding for food pellets; this effect was common to all three rat lines. Conversely, no dose of GS39783 altered lever-responding for food in any rat line.

Conclusions

These results suggest that: (a) the strength of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol differ among P, sP, and AA rats; (b) the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol in P, sP, and AA rats are differentially sensitive to treatment with baclofen and GS39783; (c) the heterogeneity in sensitivity to baclofen and GS39783 of alcohol self-administration in P, sP, and AA rats may resemble the differential effectiveness of pharmacotherapies among the different typologies of human alcoholics; (d) the GABAB receptor is part of the neural substrate mediating the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol.

Keywords: GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen; Positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor, GS39783; Operant, oral alcohol self-administration; Reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol; Alcohol-preferring P, sP, and AA rats

Introduction

The GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, has emerged as a promising pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. Recent clinical surveys and case-report studies have indeed suggested that treatment with baclofen may reduce alcohol consumption, promote abstinence from alcohol, suppress craving for alcohol, and ameliorate alcohol withdrawal symptoms and signs, including delirium tremens, in alcohol-dependent patients (Addolorato et al., 2000; 2002a; 2002b; 2003; 2006; 2007; 2011; Agabio et al., 2007; Ameisen, 2005; Ameisen and de Beaurepaire, 2010; Bucknam, 2007; Flannery et al., 2004; see however Garbutt et al., 2010; for review, see Addolorato and Leggio, 2010; Agabio et al., 2012; Muzyk et al., 2012; Tyacke et al., 2010).

At preclinical level, the lines of evidence are multiple and, for the most part, consistent. Specifically, acute or repeated administration of non-sedative doses of baclofen (or, in a few instances, of the other GABAB receptor agonists, CGP44532 and SKF97541) to rats and mice has been reported to suppress several alcohol-related behaviors as well as alcohol properties and effects, including: (a) acquisition and maintenance of alcohol drinking behavior in rats (Colombo et al., 2000; 2002; Daoust et al., 1987; Perfumi et al., 2002; Petry, 1997; Quintanilla et al., 2008; see however Smith et al., 1992; 1999); (b) the increase in alcohol intake occurring in rats after a period of forced abstinence from alcohol (the so-called “alcohol deprivation effect”, an experimental model of alcohol relapse) (Colombo et al., 2003a; 2006b); (c) the increase in alcohol intake induced in rats by treatment with opioid and cannabinoid receptor agonists (Colombo et al., 2004); (d) binge-like alcohol drinking (a single, brief drinking episode of large amounts of alcohol) in mice (Moore and Boehm, 2009; Tanchuck et al., 2011); (e) the reinforcing properties of alcohol, assessed in rats and mice exposed to different procedures of operant, oral alcohol self-administration (Anstrom et al., 2003; Besheer et al., 2004; Dean et al., 2011; Janak and Gill, 2003; Liang et al., 2006; Maccioni et al., 2005; Tanchuck et al., 2011; Walker and Koob, 2007; see however Czachowski et al., 2006); (f) the motivational properties of alcohol in rats, measured as the maximal amount of “work” (i.e., lever-pressing) that rats are willing to perform in seeking alcohol (Colombo et al., 2003b; Leite-Morris et al., 2008; Maccioni et al., 2008b; Walker and Koob, 2007); (g) reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior triggered in rats by the non-contingent presentation of a complex of cues previously associated with alcohol availability (Maccioni et al., 2008a); (h) alcohol-induced conditioned place preference (index of alcohol’s rewarding properties) in mice (Bechtholt and Cunningham, 2005); (i) alcohol-induced stimulation of locomotor activity in rats and mice (index of alcohol’s euphorigenic properties) (Arias et al., 2009; Boehm et al., 2002; Chester and Cunningham, 1999; Holstein et al., 2009; Quintanilla et al., 2008). Finally, administration of baclofen has been reported to suppress different signs of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, including anxiety-related behaviors, tremors, and seizures, in alcohol-dependent rats (Colombo et al., 2000; File et al., 1991; Knapp et al., 2007).

Recent lines of experimental evidence suggest that several “anti-alcohol” effects of baclofen and other GABAB receptor agonists may be reproduced by treatment with the positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of the GABAB receptor. These drugs apparently represent a major step forward in the pharmacology of the GABAB receptor; GABAB PAMs are devoid of substantial intrinsic agonistic activity and synergistically enhance GABA effects at GABAB receptors only in those synapses in which and when endogenous GABA is present (see Urwyler, 2011). Because of this more “physiological” mechanism of action, GABAB PAMs are expected to display a higher therapeutic index and less adverse effects than orthosteric agonists. Preclinical data collected to date apparently support this hypothesis, as hypolocomotion, sedation, and decreased responding for non-drug rewards (which represent major adverse-like effects of the orthosteric agonists of the GABAB receptor) are produced by doses of GABAB PAMs far higher than those exerting the “desired”, anxiolytic and anti-addictive effects (e.g.: Cryan et al., 2004; Malherbe et al., 2008; Paterson et al., 2008; for review, see Vlachou and Markou, 2010). This feature makes GABAB PAMs a novel class of GABAB receptor ligands with promising therapeutic potential for multiple diseases (see Froestl, 2010).

Pertaining to the “anti-alcohol” effects, acute or repeated administration of the currently available, in vivo effective GABAB PAMs (namely CGP7930, GS39783, BHF177, and rac-BHFF), reduced (a) alcohol intake under the homecage 2-bottle “alcohol vs water” choice regimen (Orrù et al., 2005) and (b) operant, oral alcohol self-administration (Liang et al., 2006; Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b; 2009; 2010a; 2010b) in selectively bred, alcohol-preferring rats (for review, see Maccioni and Colombo, 2009; Vlachou and Markou, 2010). Additionally, microinfusion of GS39783 into the ventral tegmental area suppressed alcohol-seeking behavior in Long Evans rats (Leite-Morris et al., 2009). Notably, all these effects were specific for alcohol and occurred at doses devoid of any sedative action: reduction in daily alcohol drinking by CGP7930 and GS39783 was indeed associated with a compensatory increase in daily water intake (Orrù et al., 2005); no “anti-alcohol” dose of any GABAB PAM altered the self-administration of an alternative, non-drug reinforcer (a sucrose solution) (Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b; 2009; 2010b); GS39783-induced suppression of alcohol-seeking behavior occurred at doses that did not affect the rats’ spontaneous locomotor activity (Leite-Morris et al., 2009).

The present study was intended to provide a further contribution to the preclinical characterization of the “anti-alcohol” profile of baclofen and GABAB PAMs. The GABAB PAM selected for conducting the present study was GS39783 (Urwyler et al., 2003), as it is the best characterized and most widely used GABAB PAM, especially in behavioral pharmacological studies, including those in the alcohol field (e.g.: Cryan et al., 2004; Halbout et al., 2011; Lhuillier et al., 2007; Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b; 2010a; Mombereau et al., 2004; 2007; Slattery et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2004; Voigt et al., 2011; Wierońska et al., 2011). The peculiarity of the present study was that it compared the effect of baclofen and GS39783 on operant, oral alcohol self-administration in three different lines of selectively bred, alcohol-preferring rats: Indiana alcohol-preferring (P) (see Bell et al., 2006), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) (see Colombo et al., 2006a), and Alko Alcohol (AA) (see Sommer et al., 2006) rats. Although selectively bred for the same phenotype [high alcohol preference and consumption under the 2-bottle “alcohol (10%, v/v) vs water” choice regimen with unlimited access for 24 hours/day], starting from a similar progenitor strain (Wistar rats, albeit from different vendors in different Countries), and using virtually identical selective programs (bidirectional selective outbreeding) and criteria (daily alcohol intake >4–5 g/kg; “alcohol solution vs water” preference >2:1), rats of the P, sP, and AA rats have been found to differ for multiple alcohol-related behaviors (Colombo et al., 2006a; Roman et al., 2012). Even operant alcohol self-administration (a behavior that can be intuitively considered similar to alcohol drinking) has been found to largely differ among the three rat lines (Files et al., 1997; Samson et al., 1998; Vacca et al., 2002). Together, these line divergences – likely due to the specific genetic make-up of each single line and consistent with the polygenic nature of alcohol preference – has led to hypothesize that (a) P, sP, and AA rats constitute multiple forms of high alcohol preference and intake, and (b) each rat line represents a unique phenotype different from all others. To our understanding, these multiple phenotypes would reproduce the different types, or typologies, of alcoholics (e.g.: Babor et al., 1992; Cloninger, 1987; Epstein et al., 1995; Lesch and Walter, 1996) better than a theoretical, single animal model.

Sensitivity of alcohol drinking or alcohol self-administration to pharmacological manipulations might be another attribute in which alcohol-preferring rat lines diverge. Should this be the case, this heterogeneity would replicate a common feature of alcoholic typologies: the differential effectiveness of pharmacotherapies (e.g.: Johnson et al., 2000; Kranzler et al., 2011; Rubio et al., 2005; for review, see Johnson, 2010; Pettinati, 1996; Spanagel and Kiefer, 2008). To our knowledge, attempts to compare the effect of a given drug on alcohol drinking or self-administration among different lines of alcohol-preferring rats have rarely been undertaken. Conversely, the present study tested concurrently the effect of baclofen and GS39783 on alcohol self-administration in P, sP, and AA rats. To strengthen the study validity in terms of providing information on the possible differences of sensitivity of the rat lines to baclofen and GS39783, the present study was designed so that each single aspect of the study (i.e.: rat age and gender; housing conditions; training and testing procedures of alcohol self-administration; alcohol concentration; baclofen and GS39783 doses and route of administration; experimenters involved in rat handling) was identical, with the sole exception of the rat line; accordingly, possible differences in baclofen and GS39783 effect could be attributable solely to the “rat line” variable.

Two different experimental procedures of alcohol self-administration were used: (a) fixed ratio (FR) schedule of reinforcement, in which the response requirement (RR; i.e., the “cost” of each alcohol presentation in terms of number of responses on the lever) is predetermined and kept fixed throughout the session (providing a measure of alcohol intake and of the reinforcing properties of alcohol); (b) within-session progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, in which – over the same single session – RR is progressively increased after the delivery of each reinforcer, and the lowest ratio not completed (named breakpoint) is taken as measure of motivational properties of alcohol (see Markou et al., 1993).

Further, the effect of baclofen and GS39783 on self-administration of an alternative, non-drug reinforcer (regular food pellets) was investigated in all three rat lines. This final portion of the study was intended to assess the specificity of baclofen and GS39783 effect on alcohol self-administration and to possibly rule out that the reducing effect of baclofen and GS39783 on alcohol self-administration was secondary to sedative, muscle-relaxant, or motor-incapacitating effects (an event not unlikely when testing drugs that potentiate GABA neurotransmission). Notably, previous lines of experimental evidence indicated the suitability of food self-administration to test this hypothesis, as doses of baclofen capable of suppressing cocaine self-administration were totally devoid of any effect on the self-administration of regular food pellets in rats (Brebner et al., 2000a; 2000b; Filip et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 1996; 1997).

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures employed in the present study were in accordance with the Italian law on the “Protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific reasons”.

Animals

Male P (generation 68; provided by Indiana University, School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA; n=16), sP (generation 73; n=16), and AA [generation 97; provided by the National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki, Finland; n=16] rats were used. P and AA rats reached the Cagliari facility at the age of 45 days. Rats were alcohol-naive before the start of the study. All rats were 65-days-old at the start of the study. At that time, the body weight of P, sP, and AA rats averaged 294 ± 3, 286 ± 2, and 228 ± 2 g, respectively. Rats were housed 4 per cage in standard plastic cages with wood chip bedding. The animal facility was under an inverted 12:12 hour light-dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 p.m.), at a constant temperature of 22 ± 2°C and relative humidity of approximately 60%. Over the 1-week period preceding the start of the study, rats were extensively habituated to handling, intraperitoneal injections, and intragastric infusions (by a metal gavage). Food pellets (Mucedola, Settimo Milanese, Italy) and water were always available in the homecage, except as noted.

Apparatus

Alcohol self-administration sessions were conducted in modular chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) located in sound-attenuated cubicles, with fans for ventilation and background white noise. The front panel of each chamber was equipped with (a) two retractable response levers, (b) one dual-cup liquid receptacle positioned between the two levers, and (c) two stimulus lights (one green and one white) mounted above each lever. The liquid receptacle was connected by polyethylene tubes to two syringe pumps located outside the chamber. A white house light was centered at the top of the back wall of each chamber. For half of the rats of each line, the right lever was associated with alcohol, and achievement of RR (a) activated the alcohol pump, resulting in the delivery of 0.1 ml alcohol solution, and (b) switched on the green light for the 2-s period of alcohol delivery; for these rats, the left lever was associated with water, and achievement of RR (a) activated the water pump, resulting in the delivery of 0.1 ml water, and (b) switched on the white light for the 2-s period of water delivery. The study design was counterbalanced so that the opposite condition was applied to the other half of the rats (left lever: alcohol; right lever: water).

Food self-administration sessions were conducted in modular chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) located in sound-attenuated cubicles, with fans for ventilation and background white noise. The front panel of each chamber was equipped with (a) two retractable response levers, (b) one food trough positioned between the two levers, and (c) two stimulus lights (one red and one blue) mounted above each lever. A white house light was centered at the top of the back wall of each chamber. For half of the rats of each line, the right lever was associated with food, and achievement of RR (a) activated the food dispenser, resulting in the delivery of a 45-mg pellet (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and (b) switched on the red light for the period of food delivery; for these rats, the left lever was inactive (lever responses was recorded, but had no programmed consequences). The study design was counterbalanced so that the opposite condition was applied to the other half of the rats (left lever: food; right lever: inactive).

Sequence of training and testing phases

Rats of all lines underwent the following sequence of training and testing: (a) alcohol self-administration training and maintenance; (b) testing baclofen under FR schedule of alcohol reinforcement; (c) testing GS39783 under FR schedule of alcohol reinforcement; (d) testing baclofen under PR schedule of alcohol reinforcement; (e) testing GS39783 under PR schedule of alcohol reinforcement; (f) food self-administration training and maintenance; (g) testing baclofen under FR schedule of food reinforcement; (h) testing GS39783 under FR schedule of food reinforcement. The entire study took approximately 9 months.

Experimental procedures

Alcohol self-administration

The procedure of alcohol self-administration used in the present study was identical to that conventionally employed in this laboratory with sP rats (e.g.: Maccioni et al., 2010b). Rats of each line were initially exposed to the homecage 2-bottle “alcohol vs water” choice regimen with unlimited access for 24 hours/day and 10 consecutive days. The alcohol solution was presented at a concentration of 10% (v/v). This initial phase was conducted to allow the rats to become accustomed to the taste of alcohol and start to experience its pharmacological effects, in order to possibly shorten the subsequent auto-shaping phase of the operant procedure.

Training and maintenance phase

Immediately after the 2-bottle choice regimen, rats were introduced into the operant chambers and trained to lever-press for alcohol. Self-administration sessions lasted 30 min (with the sole exception of the very first session that lasted 120 min) and were conducted 5 days per week (Monday to Friday) during the first 4–6 hours of the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Rats were deprived of food pellets and water during the 18 hours before the first session in the operant chamber. Rats were initially exposed to an FR1 schedule of reinforcement for 10% (v/v) alcohol for a number of consecutive daily sessions until they reached the criterion of earning 40 reinforcers. FR was then increased to FR2 and FR4; advancement to the subsequent step occurred any time the above criterion was met. Subsequently, the alcohol solution was presented at the final concentration of 15% (v/v). Rats were then exposed to 4 consecutive sessions during which the water lever alone or the alcohol lever alone was available every other day; water and alcohol were available on FR1 and FR4, respectively. From then onwards, both levers were concomitantly available (maintenance phase); these sessions were conducted with FR1 and FR4 on the water and alcohol lever, respectively. This maintenance phase lasted for 20–30 self-administration sessions and preceded the testing phase. At the end of the maintenance phase, rats of each line were selected for inclusion in the pharmacological experiments; specifically, the 12 rats of each line displaying the most stable responding behavior over the last 5 daily sessions (less than 25% daily difference) were selected.

Testing under the FR schedule

During the test sessions under the FR schedule of reinforcement, RR on the water and alcohol lever was maintained at FR1 and FR4, respectively. Test sessions lasted 30 min and were conducted on Fridays. All four doses of baclofen or GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. Four (Monday to Thursday) regular self-administration sessions (with FR1 and FR4 on the water and alcohol lever, respectively, and no drug treatment) elapsed between test sessions. After each test session, alcohol self-administration rapidly recovered to baseline levels. Measured variables were: (a) total number of responses on each lever (alcohol and water); (b) amount of self-administered alcohol and water (expressed in g/kg pure alcohol and ml/kg water, respectively, and determined from the number of reinforcers); (c) latency (expressed in s) to the first response on the alcohol lever.

Testing under the PR schedule

During the test sessions under the PR schedule of reinforcement, RR on the alcohol lever was increased progressively over the session according to the procedure described by Richardson and Roberts (1996); namely, RR was increased as follows: 4, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, etc. During the test sessions, the water lever was inactive (lever responses was recorded, but had no programmed consequences). Test sessions lasted 60 min; longer times were not required as previous data (Maccioni et al., 2009) indicated that lever-responding for alcohol in sP rats exposed to the PR schedule of reinforcement used in the present study reached its plateau within 10 min. Test sessions were conducted on Fridays. All four doses of baclofen or GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. Four (Monday to Thursday) regular self-administration sessions (with FR1 and FR4 on the water and alcohol lever, respectively, and no drug treatment) elapsed between test sessions. After each test session, alcohol self-administration rapidly recovered to baseline levels. Measured variables were: (a) total number of responses on each lever (alcohol lever and inactive lever); (b) breakpoint for alcohol, defined as the lowest RR not achieved by the rat on the alcohol lever; (c) latency (expressed in s) to the first response on the alcohol lever.

Food self-administration

Immediately after the alcohol self-administration experiments, rats of all lines were left undisturbed in their homecage for 7 days and given a restricted amount of food, resulting in a reduction of their body weight, over this 7-day period, of approximately 10%. Rats were maintained under this regimen of restricted food availability also over the course of the food self-administration study, during which a dosed amount of food was provided in the homecage approximately 60 min after the end of the self-administration session (see below). Food deprivation was used to motivate lever-responding for food pellets.

After the 7-day interval period, rats were introduced into the operant chambers and trained to lever-press for food. Self-administration sessions lasted 30 min and were conducted 5 days per week (Monday to Friday) during the first 4–6 hours of the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Rats were exposed to the FR4 schedule of reinforcement for 10 consecutive daily sessions (maintenance phase). In each session, a maximum of 50 reinforcers was available.

Test sessions followed the maintenance phase. Test sessions were identical to those of the maintenance phase, as FR on the food lever and maximal amount of available reinforcers were equal to FR4 and 50, respectively. Test sessions lasted 30 min and were conducted on Fridays. All four doses of baclofen or GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. Four (Monday to Thursday) regular self-administration sessions (no drug treatment) elapsed between test sessions. After each test session, food self-administration rapidly recovered to baseline levels. Measured variables were: (a) total number of responses on each lever (food lever and inactive lever); (b) latency (expressed in s) to the first response on the food lever.

Drugs

Baclofen (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was dissolved in 2 ml/kg saline and injected i.p. at the doses of 0, 1, 1.7, and 3 mg/kg 30 min before the start of the test session. Baclofen was administered intraperitoneally as this route of administration has been consistently used in all studies testing the “anti-alcohol” effects of baclofen in P (Liang et al., 2006) and sP (e.g.: Colombo et al., 2000; 2002; 2003a; 2003b; 2004; 2006b; Maccioni et al., 2005; 2008a; 2008b) rats.

GS39783 (synthesized in house by CM, SP, and FC) was suspended in 2 ml/kg distilled water with a few drops of Tween 80, and administered by gavage at the doses of 0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg 60 min before the start of the session. GS39783 dose-range, pretreatment time, and route of administration were identical to those used in previous studies testing GS39783 on different parameters of alcohol self-administration in sP rats (Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b; 2010a).

Data analysis

Data on the effect of treatment with baclofen or GS39783 on (a) total number of responses on each lever (alcohol and water), (b) amount of self-administered alcohol and water, (c) breakpoint for alcohol, and (d) latency to the first response on the alcohol lever were statistically analyzed by separate 2-way (rat line; drug dose) ANOVAs with repeated measures on the factor “drug dose”, followed by the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test for post hoc comparisons.

Results

Effect of baclofen on responding for alcohol under the FR schedule

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=27.21, P<0.0001] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=33.78, P<0.0001], but not a significant interaction [F(6,99)=1.65, P>0.05], on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever. Analysis of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among vehicle-treated rat groups (0 mg/kg baclofen) indicated that P rats displayed the strongest lever-responding behavior (225.3 ± 17.2 responses), followed by sP (176.9 ± 17.2 responses) and AA (94.7 ± 10.0 responses) rats (Figure 1, panels A–C); all these line differences reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs sP rats: P<0.05; P vs AA rats: P<0.0001; sP vs AA rats: P<0.001 (LSD test)].

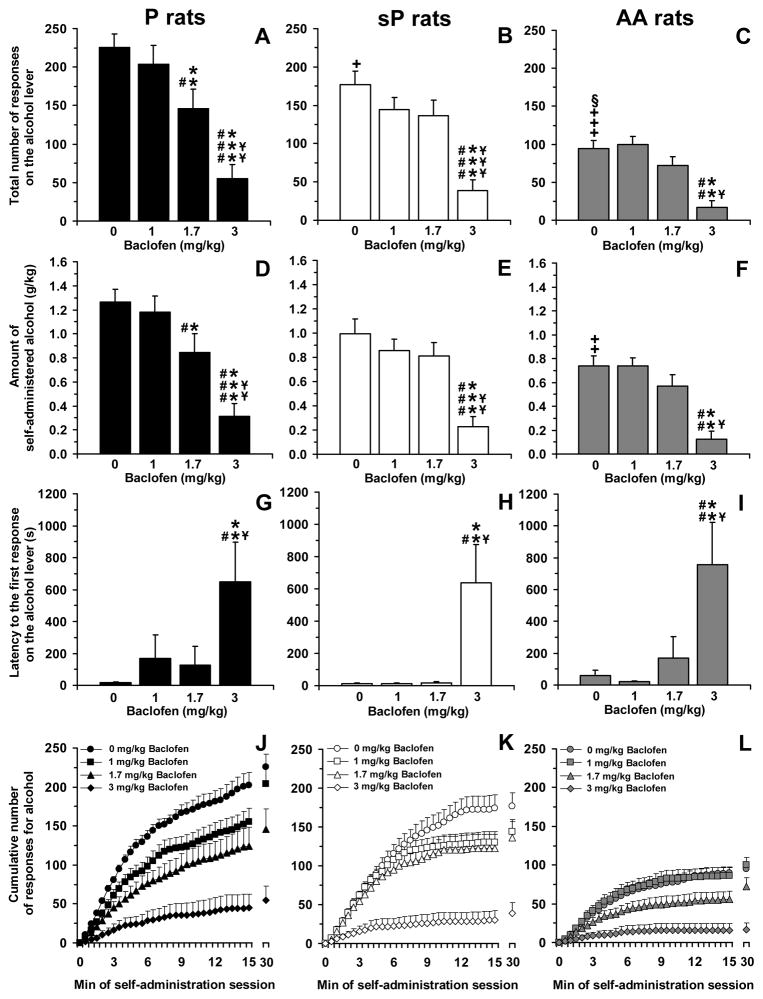

Figure 1.

Effect of treatment with the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, on total number of responses on the alcohol lever (panels A–C), amount of self-administered alcohol (panels D–F), latency to the first response on the alcohol lever (panels G–I), and cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration (panels J–L) in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P) (panels A, D, G, and J), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) (panels B, E, H, and K), and Alko Alcohol (AA) (panels C, F, I, and L) rats. Rats were initially trained to lever-press for oral alcohol (15% v/v, in water) [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] and water (FR1) in daily 30-min sessions; once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with baclofen (0, 1, 1.7, and 3 mg/kg; i.p.) under the same FR schedule of reinforcement. All doses of baclofen were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. In panels J–L, the first 15 min of the sessions were divided into 30 time intervals of 30 s each. Each bar or point is the mean ± SEM of n=12 rats. +: P<0.05, ++: P<0.001, and +++: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated P rats (LSD test); §: P<0.001 with respect to vehicle-treated sP rats (LSD test); *: P<0.01,**: P<0.005, and ***: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated rats of the same line (LSD test); #: P<0.05, ##: P<0.001, and ###: P<0.0001 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 1 mg/kg baclofen (LSD test); ¥: P<0.05, ¥¥: P<0.001, and ¥¥¥: P<0.0001 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen (LSD test).

Treatment with baclofen differentially affected the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among the three rat lines, with P rats being the most sensitive to the reducing effect of baclofen. Indeed, although treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen suppressed lever-responding for alcohol to a similar extent among all rat lines [75–80% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001 in P and sP rats, P<0.005 in AA rats (LSD test)] (Figure 1, panels A–C), the intermediate dose of 1.7 mg/kg baclofen produced a statistically significant reduction only in P rats (approximately 35% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.005, LSD test) (Figure 1, panel A); conversely, 1.7 mg/kg baclofen produced only a tendency (P=0.097, LSD test) toward a reduction in sP rats (Figure 1, panel B) and no effect in AA rats (Figure 1, panel C).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=13.94, P<0.0001] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=31.51, P<0.0001], but not a significant interaction [F(6,99)=0.70, P>0.05], on the amount of self-administered alcohol. As predicted on the basis of the lever-responding data, the amount of alcohol self-administered by vehicle-treated rat groups was highest in P (1.26 ± 0.11 g/kg), intermediate in sP (1.00 ± 0.12 g/kg), and lowest in AA (0.74 ± 0.08 g/kg) rats (Figure 1, panels D–F); the difference between P and AA rats reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis (P<0.001, LSD test).

Treatment with baclofen differentially affected the amount of self-adminstered alcohol among the three rat lines. While treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen suppressed the amount of self-administered alcohol to a similar extent among all rat lines [75–85% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001 in P and sP rats, P<0.005 in AA rats (LSD test)] (Figure 1, panels D–F), treatment with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen reduced the amount of self-administered alcohol only in P rats (approximately 35% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.01, LSD test) (Figure 1, panel D).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of baclofen dose [F(3,99)=14.87, P<0.0001], but not rat line [F(2,33)=0.33, P>0.05], and no significant interaction [F(6,99)=0.19, P>0.05], on latency to the first response on the alcohol lever. Vehicle-treated P and sP rats tended to display shorter latencies to the first response on the alcohol lever (16.1 ± 6.9 and 12.1 ± 2.9 s, respectively) than AA rats (57.4 ± 34.3 s) (Figure 1, panels G–I).

Treatment with baclofen similarly affected the latency to the first response on the alcohol lever in the three rat lines. Specifically, administration of the 3-mg/kg baclofen dose resulted in substantial and comparable increases in latency [P<0.005 (LSD test) in all rat lines]; conversely, the 1- and 1.7-mg/kg baclofen doses were devoid of any delaying effect on latency (Figure 1, panels G–I).

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns suggests that, among vehicle-treated rat groups, frequency in lever-responding during the initial phase of the session (i.e., the time period during which lever-responding was more intense) was highest in P, intermediate in sP, and lowest in AA rats (Figure 1, panels J–L). Administration of 1 mg/kg baclofen slowed the frequency in lever-responding for alcohol in P rats (Figure 1, panel J), an effect confirmed by statistical analysis of the number of responses on the alcohol lever over the first 5 min of the session (data not shown).

Finally, responding for water was negligible (averaging <5 responses per session in all rat lines); nevertheless, ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=8.20, P<0.005] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=5.18, P<0.005], but not a significant interaction [F(6,99)=2.15, P>0.05], on the total number of responses on the water lever. Vehicle-treated P rats responded on the water-associated lever (4.7 ± 1.0) more times than vehicle-treated sP (1.1 ± 0.3; P<0.0005, LSD test) and AA (1.2 ± 0.4; P<0.0005, LSD test) rats. Treatment with baclofen exerted mixed effects on the total number of responses on the water lever: slight reduction in P rats treated with 1.7 and 3 mg/kg baclofen [2.7 ± 0.6 and 1.7 ± 0.8, respectively; P<0.05 with respect to vehicle-treated rats (LSD test)], no effect in sP rats at any baclofen dose, and a slight increase in AA rats treated with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen [3.6 ± 1.2; P<0.05 with respect to vehicle-treated rats (LSD test)].

Effect of baclofen on responding for alcohol under the PR schedule

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=11.35, P<0.0005] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=42.28, P<0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=2.52, P<0.05], on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever. Analysis of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among vehicle-treated rat groups (0 mg/kg baclofen) indicated that P rats displayed the strongest lever-responding behavior (291.0 ± 20.9 responses), followed by sP (197.9 ± 15.2 responses) and AA (170.5 ± 19.6 responses) rats (Figure 2, panels A–C); differences between P rats and the other two rat lines reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs sP rats: P<0.005; P vs AA rats: P<0.0001 (LSD test)].

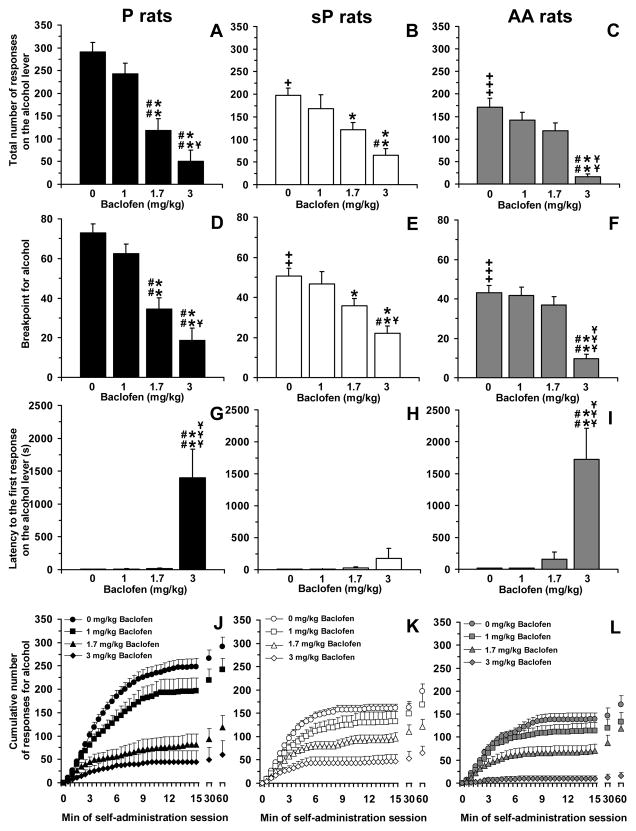

Figure 2.

Effect of treatment with the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, on total number of responses on the alcohol lever (panels A–C), breakpoint for alcohol (panels D–F), latency to the first response on the alcohol lever (panels G–I), and cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration (panels J–L) in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P) (panels A, D, G, and J), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) (panels B, E, H, and K), and Alko Alcohol (AA) (panels C, F, I, and L) rats. Rats were initially trained to lever-press for oral alcohol (15% v/v, in water) [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] and water (FR1) in daily 30-min sessions; once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with baclofen (0, 1, 1.7, and 3 mg/kg; i.p.) under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, in which the response requirement was increased progressively over a 60-min session. Breakpoint was defined as the lowest response requirement not achieved by the rat. All doses of baclofen were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. In panels J–L, the first 15 min of the sessions were divided into 30 time intervals of 30 s each. Each bar or point is the mean ± SEM of n=12 rats. +: P<0.005, ++: P<0.001, and +++: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated P rats (LSD test); *: P<0.05 and **: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated rats of the same line (LSD test); #: P<0.001 and ##: P<0.0001 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 1 mg/kg baclofen (LSD test); ¥: P<0.05, ¥¥: P<0.001, and ¥¥¥: P<0.0001 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen (LSD test).

Treatment with baclofen differentially affected the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among the three rat lines, with P rats being again the most sensitive to the reducing effect of baclofen. As seen in the “FR” experiment, treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen suppressed lever-responding for alcohol in all rat lines [70–90% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001 (LSD test) in all rat lines] (Figure 2, panels A–C). Conversely, the intermediate dose of 1.7 mg/kg baclofen reduced the total number of responses on the alcohol lever in P (approximately 60% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel A) and sP (approximately 40% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.05, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel B) rats; a tendency (P=0.078, LSD test) toward a reduction in the total number of responses on the alcohol lever was recorded in AA rats treated with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen (Figure 2, panel C).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=10.19, P<0.0005] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=43.52, P<0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=3.16, P<0.01], on breakpoint for alcohol. Analysis of breakpoint among vehicle-treated rat groups indicated that P rats displayed the highest value (73.0 ± 4.5), followed by sP (50.6 ± 3.9) and AA (43.0 ± 3.8) rats (Figure 2, panels D–F); differences between P rats and the other two rat lines reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs sP rats: P<0.001; P vs AA rats: P<0.0001 (LSD test)].

In close agreement with the data on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever, treatment with baclofen differentially affected breakpoint for alcohol among the three rat lines, with P rats being the most sensitive to baclofen effect. Treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen markedly reduced breakpoint in all rat lines [55–75% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001 (LSD test) in all rat lines] (Figure 2, panels D–F); conversely, the intermediate dose of 1.7 mg/kg baclofen reduced breakpoint only in P (approximately 50% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.0001, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel D) and sP (approximately 30% lower than in vehicle-treated rats; P<0.05, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel E) rats, while it was virtually ineffective in AA rats (Figure 2, panel F).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=5.41, P<0.01] and baclofen dose [F(3,99)=21.66, P<0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=4.06, P<0.005], on latency to the first response on the alcohol lever. Latency was relatively short and similar among vehicle-treated P, sP, and AA rats (7.6 ± 2.8, 9.4 ± 1.8, and 15.9 ± 4.4 s, respectively) (Figure 2, panels G–I).

Treatment with baclofen differentially affected the latency to the first response on the alcohol lever among the three rat lines. Indeed, no dose of baclofen altered latency in sP rats (Figure 2, panel H); conversely, treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen, but not lower doses, resulted in substantial increases in latency in P (P<0.0001, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel G) and AA (P<0.0001, LSD test) (Figure 2, panel I) rats.

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns suggests that, among vehicle-treated rat groups, frequency in lever-responding during the initial phase of the session was higher in P than sP and AA rats (Figure 2, panels J–L). Administration of 1 mg/kg baclofen tended to slow the frequency in lever-responding for alcohol in P rats (Figure 2, panel J), an effect confirmed by statistical analysis of the number of responses on the alcohol lever over the first 5 min of the session (data not shown).

Finally, responding on the inactive lever was negligible (averaging <6 responses per session in all rat lines) and not altered by treatment with baclofen [Frat line(2,33)=0.11, P>0.05; Fbaclofen dose(3,99)=1.09, P>0.05; Finteraction(6,99)=1.41, P>0.05] (data not shown).

Effect of baclofen on responding for food under the FR schedule

All rats rapidly acquired food-maintained self-administration behavior. Over a few sessions, rats were able to earn all the 50 reinforcers within 5–10 min.

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of baclofen dose [F(3,99)=34.43, P<0.0001], but not of rat line [F(2,33)=0.80, P>0.05], and no significant interaction [F(6,99)=0.80, P>0.05], on the total number of responses on the food lever. Post hoc analysis revealed a significant reducing effect of treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen in all rat lines (P<0.05, LSD test) (Table 1), with sP rats tending to be less sensitive than P and AA rats to the reducing effect of this baclofen dose. Conversely, treatment with 1 or 1.7 mg/kg baclofen did not alter the total number of responses on the food lever in each rat line (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of treatment with the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, on the total number of responses on the food lever and latency to the first response on the food lever in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP), and Alko Alcohol (AA) rats.

| Rat line | Total number of responses on the food lever | Latency (in s) to the first response on the food lever | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baclofen (mg/kg) | Baclofen (mg/kg) | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1.7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1.7 | 3 | |

| P | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 95.8 ± 32.1* | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 641.5 ± 268.3** |

| sP | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 136.7 ± 24.1* | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 9.9 ± 3.3 |

| AA | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 94.6 ± 32.9* | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 12.4 ± 9.6 | 13.8 ± 8.1 | 422.6 ± 249.8* |

Rats were initially trained to lever-press for 45-mg food pellets [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] in daily 30-min sessions; a maximum of 50 reinforcers was available. To motivate lever-responding, rats were kept at approximately 90% of their free-feeding body weight. Once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with baclofen (0, 1, 1.7, and 3 mg/kg; i.p.) under the same FR schedule of reinforcement and with the 50-reinforcer limit. All doses of baclofen were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. Each value is the mean ± SEM of n=12 rats.

: P<0.05 and

: P<0.0005 with respect to vehicle-treated rats of the same rat line (LSD test).

Latency to the first response on the food lever was short (averaging <7 s) in vehicle-treated rats of all three lines. ANOVA revealed a significant effect of baclofen dose [F(3,99)=10.98, P<0.0001], but not of rat line [F(2,33)=3.07, P>0.05], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=3.06, P<0.01], on latency to the first response on the food lever. Post hoc analysis revealed a significant reducing effect of treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen in P (P<0.0005, LSD test) and AA (P<0.05, LSD test), but not sP, rats (Table 1). Conversely, treatment with 1 or 1.7 mg/kg baclofen did not alter the latency to the first response on the food lever in each rat line (Table 1).

Finally, responding on the inactive lever was negligible (averaging <2 responses per session in all rat lines) and not altered by treatment with baclofen [Frat line(2,33)=0.53, P>0.05; Fbaclofen dose(3,99)=0.56, P>0.05; Finteraction(6,99)=0.38, P>0.05] (data not shown).

Effect of GS39783 on responding for alcohol under the FR schedule

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=13.63, P<0.0001] and GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=33.77, P<0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=3.62, P<0.005], on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever. Analysis of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among vehicle-treated rat groups (0 mg/kg GS39783) indicated that P rats displayed the strongest lever-responding behavior (228.0 ± 15.4 responses), followed by sP (194.5 ± 22.0 responses) and AA (124.3 ± 10.1 responses) rats (Figure 3, panels A–C); differences between AA rats and the other two rat lines reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs AA rats: P<0.0001; sP vs AA rats: P<0.001 (LSD test)].

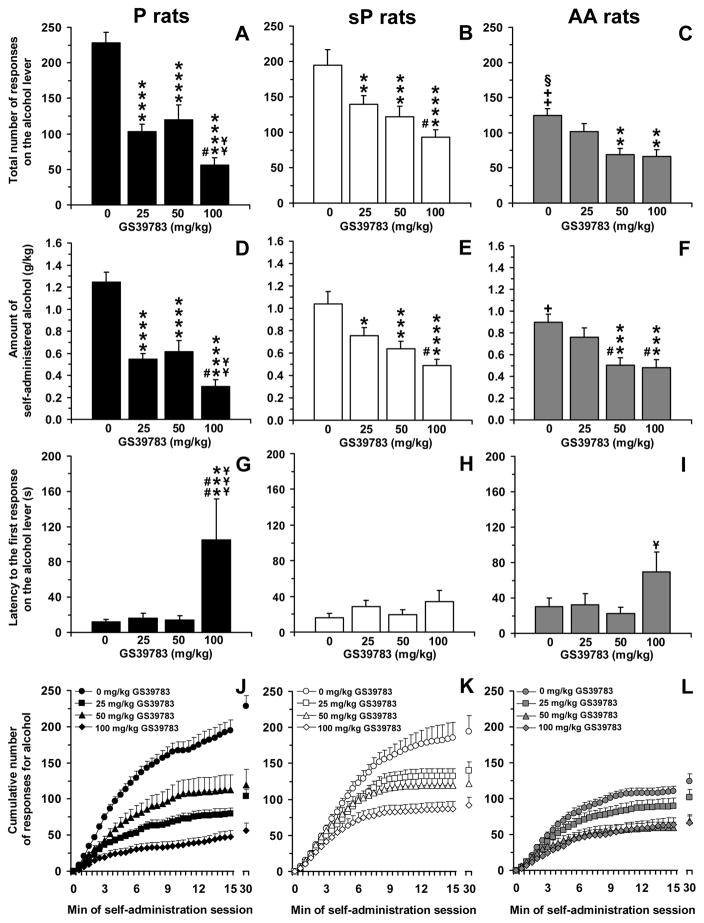

Figure 3.

Effect of treatment with the positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor, GS39783, on total number of responses on the alcohol lever (panels A–C), amount of self-administered alcohol (panels D–F), latency to the first response on the alcohol lever (panels G–I), and cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration (panels J–L) in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P) (panels A, D, G, and J), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) (panels B, E, H, and K), and Alko Alcohol (AA) (panels C, F, I, and L) rats. Rats were initially trained to lever-press for oral alcohol (15% v/v, in water) [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] and water (FR1) in daily 30-min sessions; once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with GS39783 (0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg; i.g.) under the same FR schedule of reinforcement. All doses of GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. In panels J–L, the first 15 min of the sessions were divided into 30 time intervals of 30 s each. Each bar or point is the mean ± SEM of n=12 rats. +: P<0.01 and ++: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated P rats (LSD test); §: P<0.001 with respect to vehicle-treated sP rats (LSD test); *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001, and ****: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated rats of the same line (LSD test); #: P<0.05 and ##: P<0.0005 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 25 mg/kg GS39783 (LSD test); ¥: P<0.05, ¥¥: P<0.01, and ¥¥¥: P<0.0005 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 50 mg/kg GS39783 (LSD test).

Treatment with GS39783 differentially affected the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among the three rat lines, with P rats being the most sensitive to the reducing effect of GS39783. Indeed, all three doses of GS39783 markedly reduced lever-responding for alcohol in P rats (P<0.0001, LSD test); in comparison to vehicle-treated rats, administration of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 to P rats reduced the total number of responses on the alcohol lever by approximately 55%, 50%, and 75%, respectively (Figure 3, panel A). In sP rats, treatment with 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 resulted in a reduction of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever of approximately 30% (P<0.01, LSD test), 35% (P<0.001, LSD test), and 50% (P<0.0001, LSD test), respectively, in comparison to vehicle-treated rats (Figure 3, panel B). Only the two highest doses of GS39783 reduced – by approximately 45% in comparison to vehicle-treated rats – the total number of responses on the alcohol lever in AA rats [50 mg/kg GS39783: P<0.01; 100 mg/kg GS39783: P<0.01 (LSD test)] (Figure 3, panel C).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=35.19, P<0.0001], but not of rat line [F(2,33)=0.96, P>0.05], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=3.02, P<0.01], on the amount of self-administered alcohol. As predicted on the basis of the lever-responding data, the amount of alcohol self-administered by vehicle-treated rat groups was highest in P (1.25 ± 0.09 g/kg), intermediate in sP (1.04 ± 0.11 g/kg), and lowest in AA (0.90 ± 0.07 g/kg) rats (Figure 3, panels D–F); the only significant line difference at post hoc analysis was recorded between P and AA rats (P<0.01, LSD test).

Treatment with GS39783 differentially affected the amount of self-administered alcohol among the three rat lines. It was maximally potent and effective in P rats, in which all three GS39783 doses markedly reduced alcohol consumption (P<0.0001, LSD test); in comparison to vehicle-treated rats, administration of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 to P rats reduced the amount of self-administered alcohol by approximately 55%, 50%, and 75%, respectively (Figure 3, panel D). In sP rats, treatment with 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 reduced the amount of self-administered alcohol, in comparison to vehicle-treated rats, by approximately 25% (P<0.05, LSD test), 40% (P<0.001, LSD test), and 55% (P<0.0001, LSD test), respectively (Figure 3, panel E). In AA rats, treatment with the two highest doses of GS39783 reduced the amount of self-administered alcohol by approximately 45% in comparison to vehicle-treated rats (50 and 100 mg/kg GS39783: P<0.001, LSD test) (Figure 3, panel F).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=6.58, P<0.0005], but not of rat line [F(2,33)=0.76, P>0.05] and no significant interaction [F(6,99)=1.48, P>0.05] on latency to the first response on the alcohol lever. Vehicle-treated P and sP rats tended to display shorter latencies to the first response on the alcohol lever (11.8 ± 3.1 and 16.0 ± 4.7 s, respectively) than AA rats (30.0 ± 10.0 s) (Figure 3, panels G–I).

Post hoc analysis revealed that the only alteration in the latency to the first response on the alcohol lever occurred in P rats and at the highest GS39783 dose (100 mg/kg) (P<0.001, LSD test) (Figure 3, panel G).

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns suggests that, among the vehicle-treated rat groups, frequency in lever-responding during the initial phase of the session was higher in P and sP than AA rats (Figure 3, panels J–L). Cumulative response patterns also highlight the extensive reducing effect of all doses of GS39783 on frequency on lever-responding for alcohol in P rats during the initial phase of the session (Figure 3, panel J).

Finally, responding for water was negligible (averaging <5 responses per session in all rat lines); nevertheless, ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=3.90, P<0.05], but not GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=1.67, P>0.05], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=2.45, P<0.05]. Vehicle-treated sP rats responded on the water-associated lever (1.1 ± 0.3) less times than vehicle-treated P (4.2 ± 0.9; P<0.005, LSD test) and AA (3.1 ± 0.8; P<0.05, LSD test) rats. Treatment with 50 and 100 mg/kg GS39783 produced a reduction only in P rats [1.3 ± 0.5 and 1.4 ± 0.5, respectively; P<0.005 with respect to vehicle-treated rats (LSD test)]; no effect was recorded in sP and AA rats at any GS39783 dose (data not shown).

Effect of GS39783 on responding for alcohol under the PR schedule

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=3.84, P<0.05] and GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=27.51, P<0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=4.72, P<0.0005], on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever. Analysis of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among vehicle-treated rat groups (0 mg/kg GS39783) indicated that P rats displayed the strongest lever-responding behavior (212.6 ± 15.0 responses), followed by sP (162.2 ± 11.1 responses) and AA (108.5 ± 4.1 responses) rats (Figure 4, panels AC); all these line differences reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs sP rats: P<0.01; P vs AA rats: P<0.0001; sP vs AA rats: P<0.01 (LSD test)].

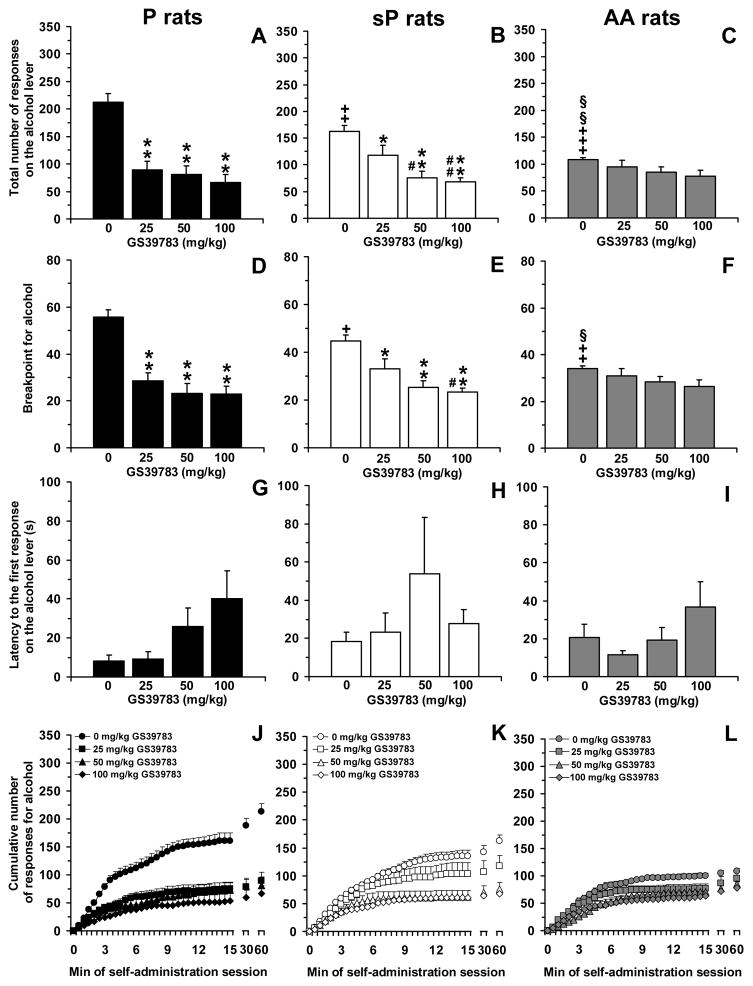

Figure 4.

Effect of treatment with the positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor, GS39783, on total number of responses on the alcohol lever (panels A–C), breakpoint for alcohol (panels D–F), latency to the first response on the alcohol lever (panels G–I), and cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration (panels J–L) in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P) (panels A, D, G, and J), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP) (panels B, E, H, and K), and Alko Alcohol (AA) (panels C, F, I, and L) rats. Rats were initially trained to lever-press for oral alcohol (15% v/v, in water) [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] and water (FR1) in daily 30-min sessions; once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with GS39783 (0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg; i.g.) under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, in which the response requirement was increased progressively over a 60-min session. Breakpoint was defined as the lowest response requirement not achieved by the rat. All doses of GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. In panels J–L, the first 15 min of the sessions were divided into 30 time intervals of 30 s each. Each bar or point is the mean ± SEM of n=12 rats. +: P<0.05, ++: P<0.01, and +++: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated P rats (LSD test); §: P<0.05 and §§: P<0.01 with respect to vehicle-treated sP rats (LSD test); *: P<0.05 and **: P<0.0001 with respect to vehicle-treated rats of the same line (LSD test); #: P<0.05 and ##: P<0.01 with respect to rats of the same line treated with 25 mg/kg GS39783 (LSD test).

Treatment with GS39783 differentially affected the total number of responses on the alcohol lever among the three rat lines, with P rats being again the most sensitive to the reducing effect of GS39783. Accordingly, all three doses of GS39783 markedly reduced lever-responding for alcohol (P<0.0001, LSD test); as seen in the “FR” experiment, dose-dependence was modest and magnitude of reduction in the total number of responses on the alcohol lever, in comparison to vehicle-treated rats, averaged 60–70% at each GS39783 dose (Figure 4, panel A). In sP rats, treatment with 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 reduced the total number of responses on the alcohol lever by approximately 30% (P<0.05, LSD test), 55% (P<0.0001, LSD test), and 60% (P<0.0001, LSD test), respectively, in comparison to vehicle-treated rats (Figure 4, panel B). In AA rats, treatment with GS39783 had no effect on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever, unless a slight tendency (P=0.11, LSD test) toward a reduction in the rat group treated with 100 mg/kg GS39783 (Figure 4, panel C).

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=26.56, P<0.0001], but not of rat line [F(2,33)=1.16, P>0.05], and a significant interaction [F(6,99)=4.18, P<0.001], on breakpoint for alcohol. Analysis of breakpoint among vehicle-treated rat groups indicated that P rats displayed the highest value (55.6 ± 3.1), followed by sP (44.7 ± 2.5) and AA (34.0 ± 1.0) rats (Figure 4, panels D–F); all these line differences reached statistical significance at post hoc analysis [P vs sP rats: P<0.05; P vs AA rats: P<0.0001; sP vs AA rats: P<0.05 (LSD test)].

In close agreement with data on the total number of responses on the alcohol lever, treatment with GS39783 differentially affected breakpoint for alcohol among the three rat lines, with P rats being the most sensitive to GS39783 effect. Indeed, all three doses of GS39783 reduced, by 50–60% with respect to vehicle-treated rats, breakpoint for alcohol in P rats (P<0.0001, LSD test) (Figure 4, panel D). In sP rats, treatment with 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg GS39783 reduced breakpoint for alcohol by approximately 25% (P<0.05, LSD test), 45% (P<0.0001, LSD test), and 50% (P<0.0001, LSD test), respectively, in comparison to vehicle-treated rats (Figure 4, panel E). In AA rats, treatment with GS39783 had no effect on breakpoint for alcohol, except for a slight tendency (P=0.09, LSD test) toward a reduction in the rat group treated with 100 mg/kg GS39783 (Figure 4, panel F).

ANOVA failed to reveal any significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=1.11, P>0.05] and GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=2.47, P>0.05], and significant interaction [F(6,99)=0.84, P>0.05], on latency to the first response on the alcohol lever. Values were relatively similar among the vehicle-treated rats of all three lines (8.3 ± 3.1, 18.5 ± 4.9, and 20.7 ± 6.8 s in P, sP, and AA rats, respectively) (Figure 4, panels G–I).

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns suggests that, among the vehicle-treated rat groups, frequency in lever-responding during the initial phase of the session was higher in P than sP and AA rats (Figure 4, panels J–L). Cumulative response patterns also suggest that the extensive reducing effect of all doses of GS39783 on frequency in lever-responding for alcohol in P rats was maintained throughout the entire session (Figure 4, panel J).

Finally, responding on the inactive lever was negligible (averaging <8 responses per session in all rat lines); nevertheless, ANOVA revealed a significant effect of rat line [F(2,33)=8.20, P<0.005], but not GS39783 dose [F(3,99)=1.75, P>0.05], and no significant interaction [F(6,99)=1.71, P>0.05]. Vehicle-treated P rats responded on the inactive lever (7.9 ± 1.3) more times than vehicle-treated sP (1.8 ± 0.7; P<0.0005, LSD test) and AA (2.9 ± 0.8; P<0.005, LSD test) rats.

Effect of GS39783 on responding for food under the FR schedule

No dose of GS39783 affected, even minimally, the total number of responses on the food lever: all rats of each line completed the RR and earned the 50 reinforcers (Table 2). Latency to the first response on the food lever was short (averaging <5 s) in vehicle-treated rats of all three lines. ANOVA revealed a slightly significant effect of rat line [F(2,21)=3.93, P<0.05], but not of GS39783 dose [F(3,63)=0.35, P>0.05], and no significant interaction [F(6,63)=1.05, P>0.05], on latency to the first response on the food lever (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of treatment with the positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor, GS39783, on the total number of responses on the food lever and latency to the first response on the food lever in selectively bred, Indiana alcohol-preferring (P), Sardinian alcohol-preferring (sP), and Alko Alcohol (AA) rats.

| Rat line | Total number of responses on the food lever | Latency (in s) to the first response on the food lever | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS39783 (mg/kg) | GS39783 (mg/kg) | |||||||

| 0 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 100 | |

| P | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| sP | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 5.1 ± 1.3 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 0.8 |

| AA | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 200 ± 0 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 1.0 |

Rats were initially trained to lever-press for 45-mg food pellets [fixed ratio (FR) 4 (FR4)] in daily 30-min sessions; a maximum of 50 reinforcers was available. To motivate lever-responding, rats were kept at approximately 90% of their free-feeding body weight. Once self-administration behavior had stabilized, rats were tested with GS39783 (0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg; i.g.) under the same FR schedule of reinforcement and with the 50-reinforcer limit. All doses of GS39783 were tested in each rat under a Latin-square design. Each value is the mean ± SEM of n=8 rats.

Finally, responding on the inactive lever was negligible (averaging <2 responses per session in all rat lines) and not altered by treatment with GS39783 [Frat line(2,21)=0.34, P>0.05; FGS39783 dose(3,63)=0.88, P>0.05; Finteraction(6,63)=0.51, P>0.05] (data not shown).

Discussion

Comparison of basal, alcohol self-administration among P, sP, and AA rats

The first series of results generated by the present study was represented by the comparison of basal, alcohol self-administration behavior among selectively bred, alcohol-preferring P, sP, and AA rats. Data collected in vehicle (0 mg/kg baclofen or 0 mg/kg GS39783)-treated rats indeed allowed a comparison of their basal behavior to be made under both FR (measure of the reinforcing properties of alcohol) and PR (measure of the motivational properties of alcohol) schedules of reinforcement. Under both procedures, P rats clearly displayed the most robust lever-responding behavior, the largest amount of self-administered alcohol, and the highest value of breakpoint for alcohol. To quantify these differences, and taking the baclofen study as example, it can be noted that – under the FR schedule of reinforcement – total number of responses on the alcohol lever in P rats was approximately 30% and 135% higher than in sP and AA rats, respectively; amount of self-administered alcohol in P rats was approximately 25% and 65% higher than in sP and AA rats, respectively. Under the PR schedule of reinforcement, total number of responses on the alcohol lever in P rats was approximately 30% and 70% higher than in sP and AA rats, respectively; breakpoint for alcohol in P rats was approximately 40% and 65% higher than in sP and AA rats, respectively.

Additional information is provided by the comparison of the cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration in vehicle-treated rats. Data from “FR” experiments suggest that the first part of the curve (indicative of the frequency in lever-responding for alcohol during the initial phase of the session, when rats’ activity is more intense) was steeper in P than sP and AA rats; the time to the last reinforcer (indicative of the duration of lever-responding behavior) was longer in P than sP and AA rats; the plateau value (indicative of the total amount of lever-responding for alcohol) was higher in P than sP and AA rats. Large differences are also observed between the cumulative response patterns of sP and AA rats, with sP rats displaying a steeper curve, a longer time to the last reinforcer, and a higher plateau value. Data from “PR” experiments provide similar information: P rats displayed a more robust lever-responding behavior during the initial portion of the session and a higher plateau value (in close agreement with the higher value of breakpoint for alcohol recorded in this rat line) than sP and AA rats.

These comparisons suggest that alcohol had stronger reinforcing and motivational properties in P than sP and AA rats. The rank order subsequently includes sP rats and finally AA rats (to summarize, P>sP>AA rats). These results, including the rank order, are similar to those produced by a series of studies promoted some years ago by Dr. Herman H. Samson and designed to compare alcohol self-administration in several lines of alcohol-preferring rats (Files et al., 1997; Samson et al., 1998; Vacca et al., 2002). In the abovementioned series of studies, operant alcohol self-administration was induced by the rats’ exposure to the so-called “sucrose fading” procedure; at the end of the induction procedure, rats were exposed to daily alcohol self-administration sessions under FR4 schedule of reinforcement and a sequence of different alcohol concentrations. Limiting the comparison to the three rat lines used in the present study, lever-responding and amount of self-administered alcohol were highest in P rats, intermediate in sP rats, and lowest in AA rats (see Figure 7 in Vacca et al., 2002). Thus, despite remarkable methodological differences in the initiation phase of alcohol self-administration (“sucrose fading” in the studies promoted by Samson; auto-shaping in the present study) as well as in the subsequent “maintenance” phases (exposure to different alcohol concentrations in the studies promoted by Samson; stable 15% alcohol concentration in the present study), the rank of strength of alcohol reinforcing properties among P, sP, and AA rats did not differ between Samson’s studies and the present investigation.

To summarize, these results suggest and confirm that operant, oral alcohol self-administration is one of the several alcohol-related behaviors in which selectively bred, alcohol-preferring rats are found to be particularly heterogeneous. Disparities in alcohol-related behaviors, neurochemical correlates, and emotional states among alcohol-preferring rat lines include, just to mention a few, (a) sensitivity to high and sedative doses of alcohol, (b) presence, magnitude, and duration of “alcohol deprivation effect”, and (c) anxiety-related behaviors (see Colombo et al., 2006a). An additional, remarkable example of the extent to which alcohol-preferring rat lines may diverge is provided by the results of a recent study testing concurrently (i.e., rats of the same age and gender, same housing conditions, same experimental procedure, same experimenters, same environment, etc.) P, sP, AA, and HAD rats at the multivariate concentric square field (Roman et al., 2012): large differences in a number of behaviors associated with risk assessment, risk taking, and shelter seeking in a novel environment were found among the four rat lines. All together, these data confirm the heterogeneity of the different lines of alcohol-preferring rats (except, of course, alcohol drinking under the 2-bottle choice regimen, i.e. the phenotype for which they have been selectively bred), resembling and modeling the heterogeneity observed among human alcoholic subtypes (Colombo et al., 2006a; Roman et al., 2012).

Effect of baclofen on alcohol self-administration

The second goal of the present study was to compare potency and efficacy of two ligands of the GABAB receptor, the orthosteric GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, and the GABAB PAM, GS39783, in reducing alcohol self-administration among P, sP, and AA rat lines. The simultaneous testing of all three rat lines, under identical experimental conditions, is seen as a strength of the present study, as any possible difference in baclofen or GS39783 effect can be reasonably attributed to the “rat line” variable.

It clearly resulted that baclofen affected differentially the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol in P, sP, and AA rats. In both FR and PR experiments, baclofen produced its largest effects in P rats, as indicated by a dose-dependent suppression of number of responses on the alcohol lever, amount of self-administered alcohol, and breakpoint for alcohol at both 1.7 and 3 mg/kg baclofen-doses. These data are consonant with the results of a previous study (Liang et al., 2006) demonstrating the capacity of 2 and 3 mg/kg baclofen (i.p.) to reduce alcohol self-administration in P rats, without altering the latency to the first response on the alcohol lever.

Baclofen effect in sP rats resulted as being intermediate between that recorded in P and AA rats. Under the FR schedule of reinforcement, the dose-dependent nature of the reducing effect of baclofen on number of responses on the alcohol lever and amount of self-administered alcohol was somewhat less clear than in a previous study (Maccioni et al., 2005), with only the 3 mg/kg baclofen-dose reaching statistical significance at the post hoc test. Further, the results of the present study do not completely replicate the delaying effect of baclofen on the latency to the first response on the alcohol lever observed in the previous study (Maccioni et al., 2005). Conversely, under the PR schedule of reinforcement, both 1.7 and 3 mg/kg baclofen-doses significantly reduced the number of responses on the alcohol lever and breakpoint for alcohol in sP rats; these data closely replicate the results of a previous study (Maccioni et al., 2008b) and prove the sensitivity of the motivational properties of alcohol in sP rats to the reducing effect of baclofen.

The lowest baclofen efficacy in reducing the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol was detected in AA rats, in which only the highest dose tested (3 mg/kg) clearly suppressed lever-responding for alcohol, amount of self-administered alcohol, and breakpoint for alcohol.

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration reveals some additional features of baclofen effect. Data from the “FR” experiment suggest that administration of the lowest tested dose of baclofen (1 mg/kg) (a) slowed the frequency in lever-responding for alcohol in P rats and (b) tended to reduce the plateau value of lever-responding in sP rats, unravelling a baclofen action not totally disclosed by the sole analysis of the total number of responses on the alcohol lever. These data suggest that even 1 mg/kg baclofen may affect some aspects of alcohol self-administration behavior in P and sP rats. Additionally, frequency of lever-responding for alcohol was reduced by treatment with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen in all three rat lines; this effect was particularly evident in P rats. Finally, the relatively flat curves generated by treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen confirm the suppressing effect of this baclofen dose on lever-responding for alcohol. Similar conclusions can be drawn from analysis of data obtained in the “PR” experiment: (a) the 1 mg/kg baclofen-dose slowed lever-responding for alcohol in P and, to some extent, sP rats; (b) treatment with 1.7 mg/kg baclofen was markedly effective in P rats, as slope and pattern of its response curve were relatively similar to those of the response curve generated by treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen; (c) treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen produced relatively flat curves, with this effect being particularly evident in AA rats.

The rank of order of baclofen potency and efficacy in reducing alcohol self-administration among the three rat lines (P>sP>AA) reflects that of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol (see above). This similarity leads to hypothesize that baclofen was more potent and effective in reducing alcohol self-administration in those rats taking or seeking larger amounts of alcohol. This hypothesis is apparently consonant with a recent set of experimental data indicating that potency and efficacy of baclofen in reducing alcohol self-administration relied on the state of alcohol dependence of the tested rats (Walker and Koob, 2007). Specifically, baclofen proved to be more potent and effective in suppressing alcohol self-administration in Wistar rats made physically dependent on alcohol (making approximately 80 responses on the alcohol lever under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement and self-administering amounts of alcohol greater than 1.2 g/kg in 30-min sessions) than in control, alcohol-nondependent rats of the same strain (making approximately 30 responses on the alcohol lever and self-administering approximately 0.6 g/kg alcohol) (Walker and Koob, 2007). Thus, baclofen effect on alcohol self-administration appears to be positively correlated with the strength of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol: the stronger the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol, the higher the potency and effectiveness of baclofen. This view finds some similarities with clinical data. The hypothesis that baclofen may be more effective in patients affected by severe forms of alcohol dependence has indeed been advanced to reconcile the discrepancy observed among some clinical surveys: the surveys recruiting patients affected by severe alcohol dependence provided stronger evidence on the suppressing effect of baclofen on alcohol craving and consumption than those studies including individuals affected by moderate alcohol use disorders (see Addolorato and Leggio, 2010; Agabio et al., 2012; Muzyk et al., 2012; Tyacke et al., 2010).

Effect of baclofen on food self-administration

The final experiment with baclofen evaluated its effect on food self-administration. This experiment was conducted to assess the specificity of baclofen-induced suppression of alcohol self-administration and to possibly rule out that it was secondary to sedative, muscle-relaxant, or motor-incapacitating effects. To date, relatively few studies have tested the specificity of baclofen effect on the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol in rats. When investigated (Anstrom et al., 2003; Colombo et al., 2003b; Janak and Gill, 2003; Maccioni et al., 2005; 2008b), specificity appeared to be relatively modest, as treatment with baclofen reduced self-administration of and extinction responding for sucrose solutions (the non-drug reinforcers used in the previous studies) at doses and with magnitudes comparable to those of the alcohol experiments. The present study employed regular food pellets as the alternative non-drug reinforcer. This choice was based on a series of data (Brebner et al., 2000a; 2000b; Filip et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 1996; 1997) suggesting a large separation between the suppressing effect of baclofen on cocaine self-administration and the lack of any effect of the same baclofen dose-ranges on food self-administration in rats. Further, an operant procedure was preferred over a simple evaluation of locomotor activity, as lever-responding represents a more complex motor task and appears to be a more reliable method for detection of motor-incoordination and sedation. Notably, data from previous studies indicated that doses of baclofen equal to or even higher than those used in the present study did not affect, even minimally, spontaneous locomotor activity in P (Liang et al., 2006) and sP (Colombo et al., 2003a; 2003b) rats tested in an open-field arena.

To this end, rats of all three lines were maintained under a slight food-deprivation regimen and trained to lever-respond for food pellets. Treatment with 3 mg/kg baclofen reduced the number of responses on the food lever (and, subsequently, the number of earned food pellets) in all three rat lines, with sP rats appearing to be somewhat less affected than P and AA rats. Conversely, rats of each line treated with 1 and 1.7 mg/kg baclofen completed their task and earned all 50 pellets. Finally, latency to the first response on the food lever was markedly increased in P and AA, although not sP, rats treated with 3 mg/kg baclofen. These data suggest that 3 mg/kg baclofen non-specifically reduced both alcohol and food self-administration and/or produced sedative, muscle-relaxant, and motor-incoordinating effects that likely disrupted the normal rates of lever-responding. Conversely, the lack of effect of 1 and 1.7 mg/kg baclofen on lever-responding for food suggests that their effects on alcohol self-administration were specific and likely not secondary to any motor-incoordinating effect.

Effect of GS39783 on alcohol self-administration

Similarly to treatment with baclofen, treatment with GS39783 affected differentially the reinforcing (“FR” experiment) and motivational (“PR” experiment) properties of alcohol in P, sP, and AA rats. In both experiments, the rank of order of GS39783 potency and efficacy in reducing alcohol self-administration among the three rat lines was: P>sP>AA. Specifically, all three tested doses of GS39783 markedly reduced the total number of responses on the alcohol lever, amount of self-administered alcohol, and breakpoint for alcohol in P rats. All variables were more than halved at each GS39783 dose with a modest, if any, dose-dependence relationship. These data (a) extend to GS39783 previous data demonstrating that treatment with the GABAB PAM, CGP7930, reduced alcohol self-administration in P rats (Liang et al., 2006), and (b) closely replicate the high potency and efficacy of baclofen in suppressing alcohol self-administration in P rats (Liang et al., 2006; present study). Together with the results of the studies testing baclofen (Liang et al., 2006; present study), these data demonstrate that alcohol self-administration in P rats is highly sensitive to pharmacological activation of the GABAB receptor. The observed higher potency and efficacy of GS39783 (resembling that of baclofen) in P rats may also be related to, or dependent on, the strength of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol: GS39783 was indeed more potent and effective in the rat line (the P line) displaying the strongest reinforcing and motivational properties. The theoretical translation of these data to humans would suggest that GS39783 is more effective in those patients affected by severe forms of alcohol dependence.

The effect of GS39783 in sP rats resulted as being intermediately positioned between that recorded in P and AA rats. Under both schedules of reinforcement (FR and PR), treatment with GS39783 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in all variables (total number of responses on the alcohol lever, amount of self-administered alcohol, and breakpoint for alcohol), closely replicating previous sets of data (Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b). These results confirm the sensitivity of the reinforcing and motivational properties of alcohol in sP rats to the reducing effect of GS39783 and, to a larger extent, of drugs activating the GABAB receptor (Maccioni et al., 2005; 2007; 2008a; 2008b; 2009; 2010a; 2010b).

Finally, and again in good agreement with the data collected in the baclofen experiments, alcohol self-administration in AA rats was only partially affected by treatment with GS39783. In these rats, only the two highest doses of GS39783 (50 and 100 mg/kg) reduced the total number of responses on the alcohol lever and amount of self-administered alcohol in the “FR” experiment. Conversely, no more than a tendency toward a reduction in the total number of responses on the alcohol lever and breakpoint for alcohol was observed in AA rats when exposed to the PR schedule of reinforcement, suggesting that the motivational properties of alcohol in AA rats were even less affected by treatment with GS39783 than the reinforcing properties.

Analysis of the cumulative response patterns of alcohol self-administration in “FR” and “PR” experiments displays that treatment with GS39783 had two major consequences: (a) decreased frequency in lever-responding for alcohol and (b) reduced time to the last reinforcer; these effects were evident in sP and, particularly, P rats.

Effect of GS39783 on food self-administration

The results of the experiment testing GS39783 on lever-responding for food pellets are of interest, as no dose of GS39783 affected any parameter of food self-administration in any of the three rat lines. These data suggest that all the tested doses of GS39783 specifically reduced alcohol self-administration and were devoid of sedative, muscle-relaxant, and motor-incoordinating effects. The complete specificity and lack of sedative effects of GS39783 observed in the present study is consonant with several previous studies demonstrating the specificity of treatment with different GABAB PAMs, including GS39783, on the self-administration of alcohol (Maccioni et al., 2007; 2008b; 2009; 2010b), cocaine (Filip and Frankowska, 2007; Filip et al., 2007), and nicotine (Paterson et al., 2008) in rats. The specificity of action of GABAB PAMs on alcohol self-administration is a valuable feature of the “anti-alcohol” profile of this new class of compounds, as they apparently meet the ideal condition of decreasing alcohol consumption and motivation to consume alcohol (or craving for alcohol, if theoretically transposed to humans) without any influence on other appetitive or consummatory behaviors. Additionally, the lack of sedative effects at doses that reduce alcohol-seeking and -taking behaviors represents a further demonstration of the favourable side-effect profile of GABAB PAMs. Notably, specificity of the “anti-alcohol” effects and high therapeutic index are two attributes that make the pharmacological profile of GABAB PAMs rather different to, and – to some extent – preferable over, that of baclofen and other GABAB receptor agonists. Indeed, as discussed above, specificity of the reducing effect of baclofen on alcohol self-administration is limited, and separation between doses reducing alcohol self-administration and doses producing sedation, muscle-relaxation, and motor-incoordination is modest. Together, these data suggest that activation of the GABAB receptor via its positive allosteric modulatory binding site (to which GS39783 binds) may result in “anti-alcohol” effects whose potential therapeutic benefits theoretically outweigh those produced by activation of the orthosteric binding site (to which baclofen binds). Clinical studies on GABAB PAMs are now needed to assess this hypothesis.

Conclusions