Although the quality of care delivered within the Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care practices seems to be high, several components of care were identified that warrant further scrutiny on a systemic level and at individual centers.

Abstract

Purpose:

The Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care (FIQCC) was established to evaluate the quality of cancer care at the regional level across the state of Florida. This study assessed adherence to validated quality indicators in colorectal cancer (CRC) and the variability in adherence by practice site, volume, and patient age.

Methods:

The FIQCC is a consortium of 11 medical oncology practices in Florida. Medical record reviews were conducted for 507 patients diagnosed with CRC and seen as new medical oncology patients in 2006. Thirty-five indicators were evaluated individually and categorized across clinical domains and components of care.

Results:

The mean adherence for 19 of 35 individual indicators was > 85%. Pathology reports were compliant on reporting depth of tumor invasion (96%; range, 86% to 100%), grade (93%; range, 72% to 100%), and status of proximal and distal surgical resection margins (97%; range. 86% to 100%); however, documentation of lymphovascular and perineural invasion did not meet adherence standards (76%; range, 53% to 100% and 39%; range, 5% to 83%, respectively). Among patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer, documentation of the status of surgical radial margins was consistently low across sites (42%; range, 0% to 100%; P = .19). Documentation of planned treatment regimens for adjuvant chemotherapy was noted in only 58% of eligible patients.

Conclusion:

In this large regional initiative, we found high levels of adherence to more than half of the established quality indicators. Although the quality of care delivered within FIQCC practices seems to be high, several components of care were identified that warrant further scrutiny on both a systemic level and at individual centers.

Introduction

In 2011, it was estimated that more than 148,810 individuals would be diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) in the United States, and approximately 49,380 would die as a result of CRC. CRC is the second leading cause of cancer death among men and women combined,1 and survival depends on stage at diagnosis.1,2 Patients with nonmetastatic CRC have the potential to achieve long-term survival; however, the quality of cancer care they receive may affect their outcomes.3,4

The importance of quality of care for patients with cancer was highlighted by the Institute of Medicine report recommending that cancer care quality be monitored using a core set of quality of care indicators (QCIs).5 QCIs can encompass structural, process, and outcome measures5; however, process QCIs have several advantages, such as being closely related to outcome, easily modifiable, and providing clear guidance for quality improvement efforts.6 The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) established the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality (NICCQ) to develop and test a validated set of core process QCIs7,8 and the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) to conduct ongoing assessments of these QCIs within individual practices.9–13 The NICCQ validated 25 CRC-specific QCIs, with adherence ranging between 57% and 93%.8 QOPI assessed 11 QCIs at two time points 6 months apart, and improved performance was observed for several measures, with the greatest improvement seen in initially low-performing practices.12

Although QOPI has been successful in improving performance within QOPI sites, improvement of cancer care outside of QOPI may require local or regional efforts that are physician or practice driven.5 To that end, we established the Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care (FIQCC) consortium with the overall goal of evaluating and improving the quality of cancer care at the regional level in Florida.14–18 This study reports adherence to 35 validated QCIs among 507 patients with CRC and the variability in adherence by practice site, volume, and patient age.

Methods

Study Sites

The FIQCC is a consortium of 11 medical oncology practices in Florida,19 three of which are associated with academic centers (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Ethics committee approval and a waiver of consent were obtained to conduct this retrospective limited review of medical records. To maintain patient privacy, all records were coded with a unique identifier before transmission to Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL).

Selection of Quality Indicators

A panel of CRC medical and surgical oncology experts from Moffitt identified 35 CRC QCIs from validated quality indicators provided by ASCO,20 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),21–23 NICCQ,8 QOPI,13 the National Quality Forum,24 and the American College of Surgeons.25 These indicators were reviewed and approved by FIQCC study coinvestigators and collaborative site primary investigators before data collection. QCIs and sources are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Medical Record Selection and Review

Medical record reviews were conducted for all patients diagnosed with CRC with a medical oncology appointment in 2006. Patients age ≤ 18 years or those diagnosed with anal/recto-sigmoid carcinoma, synchronous, or nonadenocarcinoma malignancies were excluded. Record review and quality control procedures were conducted throughout the study as reported.17–19 In brief, the chief medical record abstractor conducted on-site training of data abstractors at each site using the comprehensive abstraction manual. Abstraction did not begin until inter-rater agreement of 70% was reached in five consecutive patient cases. The number of patient cases reviewed across sites ranged from 18 to 97.

Statistical Analyses

QCIs that measure similar clinical functions or components of care were combined to generate five unique clinical domains (diagnostic evaluation, surgery-related pathology, adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant radiotherapy, and post-treatment surveillance) and seven components of care (testing, pathology, documentation, treatment considerations, timing of care, receipt of treatment/services, and technical quality).8 Appendix Table A1 (online only) outlines which QCIs were included in each clinical domain and component of care. Mean percent adherence for each domain/component was calculated as the sum of adherence scores (ie, total number of yes answers) divided by the total number of eligible QCI questions within each domain/component. Patients who were not eligible for all QCIs within a domain/component were excluded from the mean percent adherence calculation for that domain/component. Descriptive statistics and graphical illustrations summarize all QCIs.

Compliance proportions and 95% CIs were calculated based on the exact binomial distribution. On the basis of NICCQ,8 we predetermined a threshold of 85% as compliant. Statistical comparisons of adherence across sites were performed using the exact Pearson χ2 test, with Monte Carlo estimation. Logistic regression models evaluated effects of practice site volume (low v high) and patient age (< 70 v ≥ 70 years) on each QCI by estimating an odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. All analyses used two-tailed tests, with a significance level of P < .05, and were performed using SAS (SAS 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the 507 patients with CRC (391 with colon and 116 with rectal cancers) evaluated in this study. A majority of the patients were between the ages of 56 and 75 years (54%), male (53%), and white (90%).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Colorectal Cancer (N = 507)

| Characteristic | No.* | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| ≤ 55 | 118 | 24.8 |

| 56-65 | 123 | 25.8 |

| 66-75 | 134 | 28.2 |

| > 75 | 100 | 21.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 267 | 52.7 |

| Female | 240 | 47.3 |

| Race | ||

| White | 398 | 89.0 |

| Black | 43 | 9.6 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6 | 1.4 |

| Payer | ||

| Medicare | 257 | 52.0 |

| Medicaid | 17 | 3.4 |

| Private | 195 | 39.4 |

| Self-pay | 16 | 3.2 |

| Charity | 10 | 2.0 |

| Pathologic stage† | ||

| Colon | ||

| 0/I | 23 | 6.1 |

| II | 80 | 21.3 |

| III | 151 | 40.3 |

| IV | 121 | 30.4 |

| Rectal | ||

| 0/I | 11 | 11.6 |

| II or III | 56 | 58.9 |

| IV | 28 | 29.5 |

Numbers for some characteristics may not add up to 507 because of missing data.

Pathology reports and stage were missing for 37 patients.

Quality of Care by Clinical Domains and Components of Care

QCIs were grouped into five clinical domains and seven components of care (Appendix Table A1, online only). Adherence was highest for the surgery-related pathology and adjuvant radiotherapy clinical domains (mean adherence, 91%; 95% CI, 89% to 93% and 90%; 95% CI, 86% to 94%, respectively; Table 2). The remaining clinical domains had an average adherence of 80%. High quality of care (> 85%) was observed for three components of care (ie, treatment considerations, technical quality of treatment, and pathology).

Table 2.

Quality Adherence Across Clinical Domains and Components of Care

| Measure | No. of QCIs | Eligible Patients | Adherence* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Clinical domain | ||||

| Diagnostic evaluation | 6 | 507 | 80 | 77 to 82 |

| Surgery-related pathology | 8 | 316 | 91 | 89 to 93 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 10 | 412 | 80 | 78 to 82 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 5 | 56 | 90 | 86 to 94 |

| Post-treatment surveillance | 2 | 321 | 80 | 77 to 83 |

| Component of care | ||||

| Testing | 3 | 414 | 83 | 80 to 85 |

| Pathology | 11 | 316 | 86 | 84 to 88 |

| Documentation | 6 | 507 | 83 | 80 to 85 |

| Treatment consideration | 2 | 436 | 99 | 99 to 100 |

| Timing of care | 3 | 204 | 75 | 70 to 80 |

| Receipt of treatment | 3 | 204 | 83 | 79 to 88 |

| Technical quality | 7 | 321 | 87 | 85 to 89 |

Abbreviation: QCI, quality of care indicator.

Mean percent adherence for each domain/component was calculated as the sum of adherence scores (ie, total of number of yes answers) divided by the total number of eligible QCI questions within each domain/component.

Individual Quality Indicators and Variation Across Practice Sites

Rates of adherence to individual QCIs were evaluated and presented as surgery/pathology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology (Table 3). Overall, 19 of 35 indicators had adherence rates ≥ 85%.

Table 3.

Adherence to CRC QCIs by Surgery/Pathology, Medical Oncology, and Radiation Oncology in 2006

| Indicator No.* | QCI† | Eligible Patients | Adherence (%) |

P‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Range | ||||

| Surgery/pathology | |||||

| 1 | CRC detection by screening | 507 | 14 | 0-25 | < .01 |

| 2 | Documentation of staging | 507 | 93 | 77-100 | < .01 |

| 3 | Barium enema or colonoscopy within 6 months | 414 | 87 | 63-100 | < .01 |

| 4 | Copy of pathology report in record | 321 | 98 | 93-100 | .54 |

| 5 | Depth of invasion (T level) | 316 | 96 | 86-100 | .32 |

| 6 | LVI | 316 | 76 | 53-100 | < .01 |

| 7 | PNI | 316 | 39 | 5-83 | < .01 |

| 8 | Tumor differentiation (grade) | 316 | 93 | 72-100 | < .01 |

| 9 | Radial margin for rectal cancer | 64 | 42 | 0-100 | .21 |

| 10 | Distal and proximal margin status | 316 | 97 | 86-100 | .02 |

| 11 | Removal of LNs | 316 | 97 | 82-100 | .01 |

| 12 | Examination of LNs | 305 | 100 | 100-100 | |

| 13 | No. of LNs examined | 305 | 100 | 100-100 | |

| 14 | ≥ 12 LNs examined for nonmetastatic colon cancer | 250 | 72 | 53-88 | .26 |

| 15 | Involvement of LNs (N level) | 305 | 100 | 100-100 | |

| 17 | Serum CEA before treatment for nonmetastatic CRC | 321 | 78 | 47-100 | < .01 |

| 18 | Serum CEA post-treatment for nonmetastatic CRC | 321 | 82 | 50-95 | < .06 |

| Medical oncology | |||||

| 19 | Consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy (all stages) | 436 | 95 | 77-100 | < .01 |

| 20 | Explanation for not considering for treatment (all stages) | 23 | 96 | 50-100 | .14 |

| 21 | Consent for chemotherapy | 321 | 69 | 38-100 | < .01 |

| 22 | Flow sheet for chemotherapy | 321 | 86 | 63-100 | < .01 |

| 23 | Documented planned adjuvant chemotherapy dose | 321 | 58 | 5-83 | < .01 |

| 24 | Compliance of planned dose with accepted regimens (nonmetastatic) | 110 | 65 | 0-100 | .33 |

| 25 | Documentation of BSA | 321 | 99 | 92-100 | .27 |

| 26 | Accepted regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy (nonmetastatic) | 196 | 83 | 70-95 | .50 |

| 27 | Adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks (nonmetastatic) | 196 | 66 | 33-89 | .02 |

| 28 | Accepted regimen of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (nonmetastatic rectal cancer) | 32 | 31 | 0-100 | .07 |

| 29 | Receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks of diagnosis (nonmetastatic rectal cancer) | 32 | 88 | 0-100 | .02 |

| Radiation oncology for rectal cancer | |||||

| 30 | Consideration of radiation therapy | 56 | 100 | 100-100 | |

| 32 | Consultation with radiation oncologist | 56 | 93 | 67-100 | .78 |

| 33 | Accepted dosage of radiation treatment | 52 | 71 | 38-100 | .39 |

| 34 | Receipt of neoadjuvant radiation treatment | 52 | 73 | 0-100 | .01 |

| 35 | Receipt of adjuvant radiation treatment | 52 | 29 | 0-100 | .02 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body-surface area; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRC, colorectal cancer; LN, lymph node; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PNI, perineural invasion; QCI, quality of care indicator.

Complete QCIs and indicator numbers can be found in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Indicator numbers included here for reference.

Indicators < 85% in bold font.

P for variance across sites.

Surgical and pathology indicators.

Of the 507 patient records reviewed, 93% were compliant for documentation of tumor stage, (American Joint Committee on Cancer, Dukes, or TNM status); however, compliance varied significantly by site (range, 77% to 100%; P < .002). To rule out synchronous lesions, a barium enema or colonoscopy is recommended within 6 months before or after surgical resection22,23; this had an average adherence of 87% and varied across sites (range, 63% to 100%; P < .001).

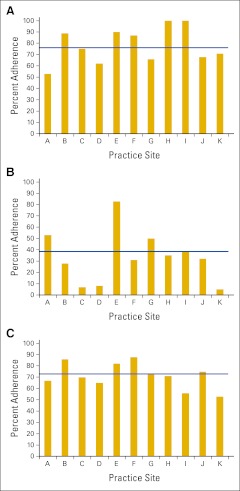

Medical oncology practices were highly compliant (98%) in maintaining copies of the surgical pathology reports confirming malignancy in their office records. Pathology reports consistently documented depth of tumor invasion, grade, and status of resection margins (Table 3). Conversely, reporting of lymphovascular (LVI) and perineural invasion (PNI) did not meet adherence standards (76%; range, 53% to 100% and 39%; range, 5% to 83%, respectively) and varied significantly across sites (P < .001; Appendix Figs 2A and 2B, online only). Notably, among the 64 patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer who had surgery and pathology reports, reporting of radial margin status was consistently low across all sites (42%; range, 0% to 100%; P = .19). High compliance (97% to 100%) was documented for all but one QCI focusing on lymph node (LN) evaluation. Consistently across all 11 sites, there was low compliance with the assessment of ≥ 12 LNs (72%; range, 53% to 88%; P = .26; Appendix Fig 2C, online only) among patients with nonmetastatic colon cancer.

Among patients with nonmetastatic CRC who had surgery (n = 321), we observed significantly variable assessment of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) before treatment, with 35% (four of 11) of the sites adhering at ≥ 85%. Adherence was slightly better for CEA assessment 6 months after treatment (82%; range, 50% to 95%), although compliance varied by site (P < .007), and only five sites (45%) adhered ≥ 85%. Assessment of CEA before and after treatment was inconsistent within individual medical oncology practices, with only one site consistently adherent to both measures (data not shown).

Medical oncology indicators.

There was documentation in the medical records that medical oncologists considered 95% of eligible patients for chemotherapy treatment (92% of those with nonmetastatic and 100% of those metastatic disease). Among patients with CRC who received chemotherapy treatment (n = 321), compliance was 99% for documenting body-surface area, 86% for having chemotherapy flow sheets, and 69% for signed/documented informed consent for treatment. Compliance with the latter two indicators varied significantly across practice sites (P = .002 and P = .001, respectively). Patient planned treatment regimen was documented in 58% of medical records (eg, name of drug and number of cycles; range, 10% to 83%; P < .001). Planned chemotherapy dosages fell within a range consistent with recommended regimens in 65% of patient cases (71 of 110). Among patients with nonmetastatic CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 196), 83% (range, 70% to 95%) were treated with a recommended regimen, and 66% (range, 33% to 89%) were treated within 8 weeks postsurgery. Recommended drug regimens were administered in 31% of patients with rectal cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 88% of patients initiated treatment within 8 weeks of a positive biopsy.

Radiation oncology indicators.

All patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (T3 and/or node positive) who had surgery (n = 56) were referred for and received radiation treatment. However, the sequence of radiation treatment, either before or after definitive surgery, varied across sites, with 54% of patients exclusively treated before or after surgery (data not shown). Across all sites, adherence standards were not met for delivery of a recommended radiation therapy regimen.

Quality Indicators by Volume and Age

Because patient volumes can affect delivery of health care,26 practice sites were categorized into those with low (< 50 medical records for patients with CRC; seven sites) or high (≥ 50 medical records for patients with CRC; four sites) patient volume. A significant relationship between QCI adherence and practice volume was found for four indicators. Documentation of PNI was more likely to occur at high-volume practices (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.1), as was documentation of a clinical trial discussion (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.9), presence of chemotherapy flow sheets (OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.2 to 4.6), and documentation of planned dose (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.7). Quality of CRC treatment has been suggested to be poorer among older patients; therefore, we evaluated quality of care according to patient age (< 70 v ≥ 70 years). Significant results were found for two indicators. Patients age ≥ 70 years were less likely to be offered participation in clinical trials (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8), whereas documentation of consent for treatment was more likely to be present for elderly patients (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.3).

Discussion

This study applied and evaluated 35 QCIs among 507 patients with CRC treated in 11 different medical oncology practices across Florida. High overall concordance rates were noted for 54% of indicators. By summarizing individual indicators in clinical domains and components of care, this study evaluated the quality of care across similar processes and identified broad target areas for improvement. Furthermore, although significant variability in adherence across practice sites was observed, adherence was rarely associated with clinical volume or patient age.

In our study, adherence to pathology indicators was high, with the exception of reporting LVI and PNI. LVI represents early manifestations of the multistep metastatic process,27 and its presence has been associated with poor prognosis in various cancer types independent of TNM staging.28–31 Similarly, PNI seems to be an important predictor of prognosis.32 Our data are consistent with the College of American Pathologists program that reported LVI (47%) and PNI (19%) as common missing elements in pathology reports.33 Conversely, documentation of LVI within the NICCQ study was > 85%.8 Documentation of LVI and PNI has been recommended since 1999, when the College of American Pathologists established a list of validated pathology elements,34 and in 2004, LVI became a required element.35,36 In 2006, pathologists should have been aware of the need to document LVI as well as PNI. Auditing and monitoring the completeness of pathology reports have been reported to improve report quality.33,37–39 Therefore, it is possible that the monitoring completed as part of FIQCC may have an impact on pathology report quality after 2006 within FIQCC sites, especially among sites that communicated results to their pathologists, some of whom are members of external pathology services.

The adequate harvest of LNs among patients with colon cancer improves staging and leads to improved outcomes.34,40 Although the significance of the 12-node benchmark remains controversial,41,42 the National Quality Forum has supported this cut point as a QCI.24 Overall, FIQCC practice sites documented the removal and examination of ≥ 12 LNs in 72% of patient cases, with 18% of practice sites (two of 11) achieving 85%. In contrast, the NCCN reported 92% adherence,43 and Vergara-Fernandez et al reported 88% in 2006, which was a significant increase from 2002 (49%).4 It is unclear why the FIQCC sites lacked adherence to this QCI. It has been shown that use of synoptic pathology reporting improves LVI and PNI reporting, and it has been linked to an increase in LNs per specimen evaluated.44,45 The use of synoptic reports by FIQCC site pathologists was not recorded as part of this study, but this provides an avenue for quality improvement efforts. Improvement efforts for pathology indicators will involve multidisciplinary input from surgeons, oncologists, and pathologists.41

Medical oncologists failed to document planned chemotherapy regimen in their notes for ≥ 85% of their patients, which is consistent with previous reports.8,12 Possible explanations include: perceptions that treatment dose and cycle are implied when the planned regimen is documented, inconsistent documentation of both the drug name and number of cycles, and/or lack of standardized documentation forms. Data are unavailable to determine the exact explanation for the lack of documentation; however, the latter explanation is unlikely, because standardized chemotherapy flow sheets were used at most sites. FIQCC has raised awareness among participating sites regarding the importance of complete documentation within the medical record, which can prevent clinical errors.

The treatment of CRC has improved as a result of targeted therapy and/or discovery of treatment response markers (eg, KRAS/BRAF mutations).46,47 Stage-specific chemotherapy guidelines (eg, NCCN guidelines) assist physicians in determining optimal treatment regimens and recommended dosages, and following these guidelines is a QCI. Among FIQCC practices that documented chemotherapy regimens, our data demonstrate moderate compliance with providing recommended chemotherapy drugs and poor compliance for use of recommended dose, dose per cycle, and number of cycles within recommended ranges. Furthermore, providing treatment within the recommended timeframe among FIQCC practice sites was lower than among NICCQ sites (79%)8 and another National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center (90%).43 Potential reasons for delayed treatment (eg, surgical complications, significant comorbid disease) in our patient cases were not available. There is evidence that delivering the recommended chemotherapy dose results in sustained improvements in outcomes among patients with potentially curable disease48; therefore, efforts to improve adherence to chemotherapy guidelines are warranted.

The treatment of rectal cancer differs in complexity from that of colon cancer because of the frequent addition of radiotherapy.22,23,49 Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is the preferred recommended approach for locally advanced rectal cancer where possible.23,49 Within FIQCC, 73% of eligible patients received neoadjuvant radiation; however, only 31% received the recommended neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment regimens. A higher percentage of patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer received recommended chemotherapy regimens when considering both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment (86%), similar to the rate within NICCQ (83%).8 Rectal radial margin status is highly predictive of local recurrence50 and a key QCI. In contrast to previous reports,4 we observed poor documentation of radial margin status. The complexity of treating rectal cancer may explain, in part, the poor adherence within FIQCC; thus, quality improvement efforts that improve the understanding of rectal cancer management are needed.

Serum CEA is a well-established tumor marker used in the surveillance of nonmetastatic CRC.20 Among FIQCC sites, there was significant variability in CEA measurement before (78%) or after treatment (82%). Adherence rates were similar, if not better, for assessment of pretreatment CEA compared with post-treatment assessment for all but one site. Our results are similar to those of QOPI, which reported 88% of patients having CEA measured within 9 months of resection.12 Viehl et al51 reported 32.8% adherence to baseline CEA measurement.

This study presents a large regional assessment of the quality of CRC care among 11 diverse medical oncology practices (ie, patient volume, geographic location, and community/academic status). We evaluated a comprehensive set of 35 validated QCIs. Medical record abstractions were systematically conducted by trained abstractors, and data collection was audited. Along with these strengths, there are some limitations that should be considered. Although CRC patient cases from 2006 may not represent current practice patterns, all QCIs were specific for that year 2006 (eg, recommended treatment regimens). The restriction to medical oncology records may have skewed the results toward lower adherence for surgical, pathologic, and/or radiation indicators; however, patient care by medical oncologists requires documentation from these specialists, and assessment of QCIs within medical oncology records is warranted. The small sample size for some indicators may have influenced the interpretation of compliance, especially for patients with rectal cancer. The findings of this study may not be generalizable to the care of all racial groups, because we were unable to assess differences by patient race or ethnicity, which should be the focus of additional quality assessment endeavors.

Although FIQCC monitors and reports on adherence to QCIs for each site, the individual practice sites have taken the lead on quality improvement efforts. As part of biannual FIQCC investigator meetings, results were provided to each of the participating sites and then reviewed in blinded fashion, with each individual site providing its site code (Appendix Fig A2, online only). Sites shared the quality data with respective institutional quality review committees (either established or inaugural) to address the issues that were raised. Each institution prioritized the identified deficits in compliance with QCIs and developed action plans for improvement. Each practice site reported a variety of quality improvement activities that were initiated after disclosure of FIQCC results from the previous retreat, such as development of treatment consent processes, altering pathology reporting to include missing elements, or improving CEA testing. A resampling of patient cases after these activities is ongoing and will help determine the effectiveness of site-initiated improvement efforts. These practice site–initiated activities seem to have improved quality when comparing a small set of QCIs among four practice sites with data from 200414 and 2006. For example, increases in compliance were observed for CEA before surgery (from 57% to 80%; P < .001) and evaluation of the colon within 6 months of treatment (from 46% to 89%; P < .001). The dissemination of results obtained within FIQCC to consortium members has improved the quality of CRC care across the state of Florida.

Overall, CRC represents a disease with substantial burden to society, and the quality of care provided after diagnosis is critical. We have successfully translated published CRC QCIs into practice within community and academic medical oncology centers across the state of Florida. Although the quality of care delivered within FIQCC practices seemed to be high, several components of care were identified that warrant further scrutiny on both a systemic level and at individual centers. The FIQCC consortium provides an excellent model of a sustainable collaboration for the assessment of cancer care quality within other hospital networks across the United States.

Acknowledgment

We thank Tracy Simpson, Christine Marsella, Suellen Sachariat, and Joe Wright for their assistance. Supported by Pfizer. Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Orlando, FL, May 29-June 2, 2009.

Appendix

Table A1.

QCIs for Patients With Colorectal Cancer

| Indicator No. | QCI |

Clinical Domain | Component of Care | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Abbreviated | ||||

| 1 | Was “colorectal cancer detected by screening?” | CRC detection by screening | a | ||

| 2 | Was “there an explicit statement of the patient's staging according to the AJCC or Dukes systems?” Or, for patients who do not have an explicit statement of staging in their medical record, is “the tumor size, lymph node status, and metastatic status documented in the medical chart?” | Documentation of staging | Diagnostic | Documentation | b,c |

| 3 | For patients who had surgical resection, was “a barium enema or colonoscopy performed within 6 mo before or 6 mo after surgery?” | Barium enema or colonoscopy within 6 months | Diagnostic | Testing | d |

| 4 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, was “there a copy of the surgical pathology report confirming malignancy in the medical oncology office chart?” | Copy of pathology report in medical record | Documentation | b,e | |

| 5 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report state the depth of invasion of the tumor?” | Depth of invasion (T level) | Diagnostic | Pathology | b,e |

| 6 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report state the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion?” | LVI | Diagnostic | Pathology | b,c |

| 7 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report state the presence or absence of perineural invasion?” | PNI | Diagnostic | Pathology | b |

| 8 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report state the differentiation of the tumor as well, moderate, or poor?” | Tumor differentiation (grade) | Diagnostic | Pathology | b |

| 9 | For patients with nonmetastatic rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report document that the radial margin of the surgical specimen is free of tumor?” | Radial margin for rectal cancer | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology, quality of treatment | b,c |

| 10 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report comment on the presence or absence of microscopic tumor cells at the resection margin?” | Distal and proximal margin status | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology, quality of treatment | b,c |

| 11 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease, did “the surgical pathology report indicate that the patient had the lymph nodes removed?” | Removal of LNs | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology | b,c |

| 12 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease who had LNs removed, did “the surgical pathology report state whether or not the lymph nodes were examined?” | Examination of LNs | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology, quality of treatment | b |

| 13 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease whose pathology report stated whether LNs were examined, did “the surgical pathology report state the number of lymph nodes examined?” | Number of LNs examined | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology, quality of treatment | b |

| 14 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon disease whose pathology report stated the number of LNs examined, “how many lymph nodes were examined?” | ≥ 12 LNs examined for nonmetastatic colon cancer | Pathology, quality of treatment | b,f | |

| 15 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease who had LNs removed, did “the surgical pathology report state whether or not the tumor involves lymph nodes?” | Involvement of LNs (N level) | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology | b,c |

| 16 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal disease whose pathology report stated whether the tumor involved LNs, did “the surgical pathology report state the number of lymph nodes involved?” | Surgery-related pathology | Pathology | b | |

| 17 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal cancer, was “there a blood test for CEA at least once prior to surgery or chemotherapy treatment?” | Serum CEA before treatment for nonmetastatic CRC | Post-treatment surveillance | Testing | d,g |

| 18 | For patients with nonmetastatic colon or rectal cancer, was “there a blood test for CEA at least once within 6 mo after the last treatment, either surgery or chemotherapy?” | Serum CEA after treatment for nonmetastatic CRC | Post-treatment surveillance | Testing | d,g |

| 19 | For patients for whom guidelines recommend use of chemotherapy, did “the physician discuss, recommend, or refer for adjuvant chemotherapy?”h,i | Consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy (all stages) | Chemotherapy | Treatment consideration | c,d |

| 20 | For patients for whom guidelines recommend use of chemotherapy but who were not referred for adjuvant chemotherapy, was “there an explicit note in the medical chart explaining why the physician did not discuss, recommend, or refer for adjuvant chemotherapy?”h,i | Explanation for not considering for treatment (all stages) | Chemotherapy | Treatment consideration | c,d |

| 21 | For patients who received chemotherapy, was “there a signed consent for treatment in the chart or a practitioner's note that treatment was discussed and patient consented to treatment?” | Consent for chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | Documentation | e |

| 22 | For patients who received chemotherapy, was “there a flow sheet with chemotherapy notes and blood counts?” | Flow sheet for chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | Documentation | e |

| 23 | For patients who received chemotherapy, was “the patient's planned dose of chemotherapy documented in the medical oncology note?” | Documented planned adjuvant chemotherapy dose | Chemotherapy | Documentation | c |

| 24 | For nonmetastatic patients who received chemotherapy and whose planned dose was documented, did “the patient's planned dose of chemotherapy, dose per cycle, and number of cycles fall within a range that is consistent with published regimens?” | Compliance of planned dose with accepted regimens (nonmetastatic) | Chemotherapy | Quality of treatment | c,d |

| 25 | For patients who received chemotherapy, was “the patient's body-surface area (BSA) documented?” | Documentation of BSA | Chemotherapy | Documentation | c |

| 26 | For patients with stage II/III colon cancer or stage II/III rectal cancer who received chemotherapy, did “the patient receive adjuvant chemotherapy with a regimen listed below?” Or was “the patient in a clinical trial of a chemotherapy agent or regimen?”j | Accepted regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy (nonmetastatic) | Chemotherapy | Receipt of treatment | c,d |

| 27 | For patients with stage II/III colon cancer or stage II/III rectal cancer who received chemotherapy, did “the patient start adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 wk after surgical resection?”j | Adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks (nonmetastatic) | Chemotherapy | Timing of care | c |

| 28 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received chemotherapy before surgical resection, did “the patient receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a regimen listed below?” | Accepted regimen of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (nonmetastatic rectal cancer) | Chemotherapy | Receipt of treatment | c,d |

| 29 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, did “the patient start neoadjuvant chemotherapy within 8 wk after first positive biopsy?” | Receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks of diagnosis (nonmetastatic rectal cancer) | Chemotherapy | Timing of care | c |

| 30 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer, did “the physician discuss, recommend, or refer for radiation?” | Consideration of radiation therapy | Radiation | Treatment consideration | c |

| 31 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who were not referred for radiation, was “there an explicit note in the medical chart explaining why the physician did not discuss, recommend, or refer for radiation?” | Radiation | Treatment consideration | c | |

| 32 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer, did “the patient have a consultation with a radiation oncologist?” | Consultation with radiation oncologist | Radiation | Treatment consideration | |

| 33 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received radiation, did “the patient receive a radiation regimen that included at least 45 Gray (Gy) over a period of 5 wk?” Or was “the patient in a clinical trial for radiation therapy?” | Accepted dosage of radiation treatment | Radiation | Receipt of treatment, quality of treatment | d |

| 34 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received radiation, did “the patient receive radiation therapy before definitive surgical excision?” | Receipt of neoadjuvant radiation treatment | Radiation | Timing of care | c |

| 35 | For patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received radiation, did “the patient receive radiation therapy after definitive surgical excision?” | Receipt of adjuvant radiation treatment | Radiation | Timing of care | c |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BSA, body-surface area; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRC, colorectal cancer; LN, lymph node; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PNI, perineural invasion; QCI, quality of care indicator.

O'Leary J: J Oncol Manag 12:7, 2003.

Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al: J Clin Oncol 24:626-634, 2006.

Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, et al: J Clin Oncol 26:3631-3637, 2008; Engstrom PF, Benson AB 3rd, Chen YJ, et al: J Natl Compr Canc Netw 3:468-491, 2005; Engstrom PF, Benson AB 3rd, Chen YJ, et al: J Natl Compr Canc Netw 3:492-508, 2005.

Neuss MN, Desch CE, McNiff KK, et al: J Clin Oncol 23:6233-6239, 2005.

Desch CE, Benson AB 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al: J Clin Oncol 23:8512-8519, 2005.

NCCN guidelines recommend patients with stages II to IV colon cancer and stages II to IV rectal cancer receive treatment with chemotherapy.

Discussion, recommendation, and referral for patients with stage III colon cancer must have occurred within 4 months of diagnosis.

Restricted to stage II colon cancer with features that increase risk of recurrence, including obstruction, perforation, T4 lesions, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, or LVI.

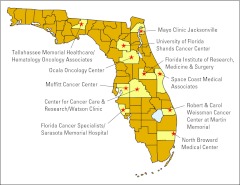

Figure A1.

The Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care is a consortium of 11 medical oncology practices across the state of Florida. Reprinted with permission.18

Figure A2.

Adherence to pathologic quality of care indicators of (A) lymphovascular (LVI), (B) perineural invasion (PNI), and (C) examination of ≥ 12 lymph nodes (LNs). Variable adherence was observed across sites for documentation of LVI (76%; range, 53% to 100%) and PNI (39%; range, 5% to 83%) in 316 patients with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer who had surgery (P < .001). Adherence to the examination of ≥ 12 LNs was consistently low (72%; range, 52% to 88%; P = .26) for patients with nonmetastatic colon cancer (n = 250).

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Thomas Cartwright, Amgen (C), Genentech (C), Eli Lilly (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Thomas Cartwright, Amgen, Genentech, Eli Lilly Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Erin M. Siegel, Paul B. Jacobsen, Mokenge Malafa, Richard Brown, Richard M. Levine, Thomas Cartwright, Guillermo Abesada-Terk Jr, George P. Kim, Carlos Alemany, Merry-Jennifer Markham, David Shibata

Financial support: Paul B. Jacobsen

Administrative support: Paul B. Jacobsen, Michelle Fletcher

Provision of study materials or patients: Mokenge Malafa, Richard Brown, Richard M. Levine, Thomas Cartwright, Guillermo Abesada-Terk Jr, George P. Kim, Carlos Alemany, Douglas Faig, Philip Sharp, Merry-Jennifer Markham

Collection and assembly of data: Erin M. Siegel, Paul B. Jacobsen, Michelle Fletcher, Ji-Hyun Lee, Jesusa Corazon R. Smith, Richard Brown, Richard M. Levine, Thomas Cartwright, Guillermo Abesada-Terk Jr, George P. Kim, Carlos Alemany, Philip Sharp, Merry-Jennifer Markham

Data analysis and interpretation: Erin M. Siegel, Paul B. Jacobsen, William J. Fulp, Ji-Hyun Lee, David Shibata

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2011. www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures/CancerFactsFigures/cancer-facts-figures-2011.

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3176–3181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vergara-Fernandez O, Swallow CJ, Victor JC, et al. Assessing outcomes following surgery for colorectal cancer using quality of care indicators. Can J Surg. 2010;53:232–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewitt M, Simone JV, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patwardhan M, Fisher DA, Mantyh CR, et al. Assessing the quality of colorectal cancer care: Do we have appropriate quality measures? (A systematic review of literature) J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:831–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider EC, Malin JL, Kahn KL, et al. Developing a system to assess the quality of cancer care: ASCO's National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2985–2991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: How can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, McNiff KK, et al. Evolution and elements of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative measure set. Cancer Control. 2009;16:312–317. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blayney DW, McNiff K, Hanauer D, et al. Implementation of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative at a university comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3802–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNiff KK, Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, et al. Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: Lessons learned from the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3832–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson JO, Neuss MN, McNiff KK, et al. Improvement in oncology practice performance through voluntary participation in the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1893–1898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuss MN, Desch CE, McNiff KK, et al. A process for measuring the quality of cancer care: The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6233–6239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen P, Shibata D, Siegel EM, et al. Measuring quality of care in the treatment of colorectal cancer: The Moffitt Quality Practice Initiative. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:60–65. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0722002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen PB, Shibata D, Siegel EM, et al. Initial evaluation of quality indicators for psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Cancer Control. 2009;16:328–334. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray JE, Laronga C, Siegel EM, et al. Degree of variability in performance on breast cancer quality indicators: Findings from the Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:247–251. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsen PB, Shibata D, Siegel EM, et al. Evaluating the quality of psychosocial care in outpatient medical oncology settings using performance indicators. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20:1221–127. doi: 10.1002/pon.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malafa MP, Corman MM, Shibata D, et al. The Florida Initiative for Quality Cancer Care: A regional project to measure and improve cancer care. Cancer Control. 2009;16:318–327. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. Fatigue, depression, and insomnia: Evidence for a symptom cluster in cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Comprehensive Cancer Network quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3631–3637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engstrom PF, Benson AB, 3rd, Chen YJ, et al. Colon cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3:468–491. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2005.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engstrom PF, Benson AB, 3rd, Chen YJ, et al. Rectal cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3:492–508. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2005.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Quality Forum. At least 12 regional lymph nodes are removed and pathologically examined for resected colon cancer. www.qualityforum.org/MeasureDetails.aspx?SubmissionId=455#k=colon+cancer.

- 25.O'Leary J. Report from the American College of Oncology Administrators' (ACOA) liaison to the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACoS-CoC): New cancer program standards highlighted. J Oncol Manag. 2003;12:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonardi MJ, McGory ML, Ko CY. Quality of care issues in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6897s–6902s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cady B. Regional lymph node metastases: A singular manifestation of the process of clinical metastases in cancer—Contemporary animal research and clinical reports suggest unifying concepts. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1790–1800. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng L, Jones TD, Lin H, et al. Lymphovascular invasion is an independent prognostic factor in prostatic adenocarcinoma. J Urol. 2005;174:2181–2185. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181215.41607.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dicken BJ, Graham K, Hamilton SM, et al. Lymphovascular invasion is associated with poor survival in gastric cancer: An application of gene-expression and tissue array techniques. Ann Surg. 2006;243:64–73. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000194087.96582.3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotan Y, Gupta A, Shariat SF, et al. Lymphovascular invasion is independently associated with overall survival, cause-specific survival, and local and distant recurrence in patients with negative lymph nodes at radical cystectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6533–6539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meguerditchian AN, Bairati I, Lagacé R, et al. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in surgically cured rectal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2005;189:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poeschl EM, Pollheimer MJ, Kornprat P, et al. Perineural invasion: Correlation with aggressive phenotype and independent prognostic variable in both colon and rectum cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e358–e360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3581. author reply e361-e362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Idowu MO, Bekeris LG, Raab S, et al. Adequacy of surgical pathology reporting of cancer: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 86 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:969–974. doi: 10.5858/2009-0412-CP.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Compton C, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Prognostic Factors Consensus Conference: Colorectal Working Group. Cancer. 2000;88:1739–1757. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000401)88:7<1739::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connolly JL, Fletcher CD. What is needed to satisfy the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (COC) requirements for the pathologic reporting of cancer specimens? Hum Pathol. 2003;34:111. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Washington MK, Berlin J, Branton P, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1539–1551. doi: 10.5858/133.10.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onerheim R, Racette P, Jacques A, et al. Improving the quality of surgical pathology reports for breast cancer: A centralized audit with feedback. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1428–1431. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1428-ITQOSP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imperato PJ, Waisman J, Wallen MD, et al. Improvements in breast cancer pathology practices among medicare patients undergoing unilateral extended simple mastectomy. Am J Med Qual. 2003;18:164–170. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imperato PJ, Waisman J, Wallen M, et al. Results of a cooperative educational program to improve prostate pathology reports among patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Community Health. 2002;27:1–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1013823409165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, et al. Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: Systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:433–441. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Kulaylat M, Rockette H, et al. Should total number of lymph nodes be used as a quality of care measure for stage III colon cancer? Ann Surg. 2009;249:559–563. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318197f2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong SL. Lymph node evaluation in colon cancer: Assessing the link between quality indicators and quality. JAMA. 2011;306:1139–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romanus D, Weiser MR, Skibber JM, et al. Concordance with NCCN colorectal cancer guidelines and ASCO/NCCN quality measures: An NCCN institutional analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:895–904. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beattie GC, McAdam TK, Elliott S, et al. Improvement in quality of colorectal cancer pathology reporting with a standardized proforma: A comparative study. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:558–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ratto C, Sofo L, Ippoliti M, et al. Accurate lymph-node detection in colorectal specimens resected for cancer is of prognostic significance. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:143–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02237119. discussion 154-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chee CE, Sinicrope FA. Targeted therapeutic agents for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallagher DJ, Kemeny N. Metastatic colorectal cancer: From improved survival to potential cure. Oncology. 2010;78:237–248. doi: 10.1159/000315730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyman GH. Impact of chemotherapy dose intensity on cancer patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:99–108. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer: College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979–994. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0979-PFICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viehl CT, Ochsner A, von Holzen U, et al. Inadequate quality of surveillance after curative surgery for colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2663–2669. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]