Completion of recommended liver imaging and carcinoembryonic antigen testing falls well below guidelines in Manitoba, whereas colonoscopy is better provided. Addressing this gap should improve outcomes for colorectal cancer survivors.

Abstract

Purpose:

Intensive surveillance after curative treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) is associated with improved overall survival. This study examined concordance with the 2005 ASCO surveillance guidelines at the population level.

Methods:

A cohort of 250 patients diagnosed with stage II or III CRC in 2004 and alive 42 months after diagnosis was identified from health administrative data in Manitoba, Canada. Colonoscopy, liver imaging, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing were assessed over 3 years. Guidelines were met if patients had at least one colonoscopy in 3 years and at least one liver imaging test and three CEA tests annually. Multivariate logistic regression assessed the effect of patient and physician characteristics and disease and treatment factors on guideline concordance.

Results:

Guidelines for colonoscopy, liver imaging, and CEA were met by 80.4%, 47.2%, and 22% of patients, respectively. Guideline concordance for colonoscopy was predicted by annual contact with a surgeon, higher income, and the diagnosis of colon (rather than rectal) cancer. Adherence was lower in those older than 70 years and with higher comorbidity. For liver imaging, significant predictors were annual contact with an oncologist, receipt of chemotherapy, and diagnosis of colon cancer. Concordance with CEA guidelines was higher with annual contact with an oncologist and high levels of family physician contact, and lower in urban residents, in those older than 70, and in those with stage II disease.

Conclusion:

Completion of recommended liver imaging and CEA testing fall well below guidelines in Manitoba, whereas colonoscopy is better provided. Addressing this gap should improve outcomes for CRC survivors.

Introduction

Improving cancer survival rates have generated an increased focus on the care of cancer survivors. One of the goals of follow-up care or surveillance after treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) is the early detection of tumor recurrence and new primary cancers at a point when further curative treatment is possible. Recurrence after curative treatment for CRC is common, with a 4-year rate of 26% reported in a recent trial.1 Three meta-analyses comparing intense and minimal follow-up have each demonstrated improved 5-year overall survival with more intense follow-up, with an absolute mortality reduction of 9% to 13%.2–4 This benefit has not been demonstrated for the surveillance of other solid tumors. Because of the diversity of “intense follow-up” protocols used in the various trials, it is not possible to infer which combination and frequency of investigations had the most impact. However, the benefit in the meta-analyses was strongest when serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing2,4 and liver imaging2–4 were added to colonoscopy. ASCO and several American and Canadian cancer authorities have published and revised guidelines for surveillance of stage II and III CRC that include all of these three tests (Table A1, online only).5–9 However, the translation of such guidelines into clinical practice faces a variety of challenges.10,11

The findings of recent studies examining real-world concordance with the ASCO guidelines are summarized in Table A2 (online only).12–15 The study by Cooper et al12 examined CRC follow-up care in a 2000-2001 cohort derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database but considered liver imaging as a nonrecommended test and lacked treatment data. The other three studies are institution-based chart reviews in Canada.13–15 To our knowledge, no study has examined concordance with all three recommended tests at a population level, particularly in a jurisdiction providing universal health care to all residents, in which adherence to follow-up testing would be expected to be higher. Further, no study has addressed the impact that contact with physicians of different specialties may have in achieving guideline-based care. The purpose of this study is to describe concordance with recommended CRC surveillance guidelines at the population level for colonoscopy, liver imaging, and CEA testing, and to assess the impact of a full array of patient and physician characteristics and disease and treatment factors.

Methods

Setting

Manitoba, Canada has a population of 1.15 million people, of whom 633,000 (55%) live in Winnipeg, the provincial capital and the only city with a population greater than 50,000.16 At the time of the study, all medical and radiation oncologists were located in Winnipeg, most working in clinics operated by CancerCare Manitoba, the provincial cancer agency. Three quarters of provincial chemotherapy was administered in outpatient clinics in Winnipeg, and the other one quarter in 16 hospitals in rural communities.17 Manitoba has a single-payer health care system with universal coverage. It has relatively low levels of immigration and emigration, making it a favorable environment in which to conduct population-level studies.

Data Sources

This is a retrospective cohort study of all patients residing in Manitoba diagnosed with stage II and III CRC in 2004. Data for these individuals were obtained from the Manitoba Cancer Registry (the Registry) and were linked with the Population Health Research Data Repository (the Repository) housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Cancer is a reportable disease in Manitoba, and the Registry captures information on all residents diagnosed with cancer, including demographics, tumor characteristics, collaborative stage,18 and basic treatment information. It has demonstrated high levels of reporting completeness.19,20 The Repository includes hospital discharge data, physician services claims, diagnostic imaging data, and vital statistics for all Manitoba residents. The quality of the data housed in the Repository has been previously demonstrated.21,22 CEA test information is available from claims data from all public and private laboratories in Manitoba that perform this assay. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba, the Health Information Privacy Committee of Manitoba Health, and the Research Resource Impact Committee of CancerCare Manitoba.

Cohort Identification

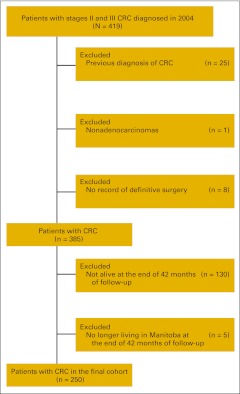

We included all patients with stage II and III adenocarcinoma of the colon, rectum, and rectosigmoid junction with a date of diagnosis in 2004. Cancer site was identified by International Classification of Diseases 10th edition codes (C18.0-18.9, C26.0, C19, C20). Rectosigmoid cancers were combined with rectal cancers in all analyses. Patients were excluded if there was a previous diagnosis of CRC in the Registry, if histology was not adenocarcinoma, and if no definitive surgery was performed (Figure A1, online only). Similar to other researchers,12 we confined our analysis to those individuals who remained alive at 42 months after diagnosis. The date of cancer recurrence is not captured in the Registry to permit censoring of individuals at that time. Although surrogate markers for recurrence such as delayed initiation of chemotherapy or cancer surgery have been used,23 these may be unreliable when verified by chart review.24

Measures

The follow-up interval examined was a 3-year period beginning with the seventh month after the date of diagnosis and ending with the 42nd month. The 3-year period was divided into 1-year intervals from seven to 18 months, 19 to 30 months, and 31 to 42 months. Tests performed in the first 6 months after diagnosis were excluded because of the possibility that they represented initial staging tests rather than routine follow-up care. Data about follow-up tests for the cohort spanned from July 2004 to June 2008. The main outcome of interest was the performance of three tests endorsed by the 2005 ASCO guidelines (Table A1): colonoscopy, liver imaging, and serum CEA. Chest imaging was not assessed because of the weaker evidence supporting its use.5 Although this ASCO guideline was formally adopted in Manitoba in 2008, it was implemented and recommended earlier by oncologists at CancerCare Manitoba. These guidelines were nonbinding, and because of slight variations between these and other published guidelines, a multidisciplinary expert panel was convened that defined an acceptable standard for surveillance testing in the province during the years of the study for the three 1-year intervals assessed:

Colonoscopy: at least one performed in the 3-year period.

Liver imaging: at least one computed tomography, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the abdomen performed in each 1-year interval.

CEA: at least three tests performed in each 1-year interval.

This intensity of surveillance is consistent with the minimum recommended in all of the published guidelines. Although complete data regarding colonoscopy and CEA testing are available, the analysis of diagnostic imaging was confined to the province's two largest cities (comprising 64% of the provincial population) because of data limitations.25 All tests are fully insured in Manitoba.

Patient variables.

Data were extracted on the following patient characteristics, which were assigned as of the date of diagnosis: age, sex, Winnipeg versus rural residence, household income, and comorbidity. Patients were assigned an income quintile based on aggregate neighborhood household income calculated from 2001 Statistics Canada Census. Comorbidity was defined by Major Adjusted Diagnostic Groups (MADG) counts26 and was calculated from physician claims and hospital discharge abstracts for a 2-year period before diagnosis.

Treatment variables.

Receipt of chemotherapy and radiation therapy was defined as one or more treatments of either given in the 12-month period after diagnosis. Treatment provided later than this would be more likely to represent treatment of recurrent disease. Chemotherapy provision was captured both from physician claims data and from the Registry. Radiation therapy provision was captured from procedure codes in the Registry.

Physician variables.

We examined outpatient physician visits during the follow-up care period by identifying all relevant billing tariff codes for each specialty group: family physicians (FPs), medical and radiation oncologists, surgeons, and general internists, who in Manitoba function as consultants. Involvement in follow-up care was analyzed as a dichotomous variable. Oncologists, surgeons, and internists were defined as involved if there was one or more patient visit with that physician group in each 1-year interval. Because of the high frequency of visits with FPs, their involvement was defined as high if the number of visits was above the median for the cohort in all 1-year intervals; otherwise, it was considered low.

Data Analysis

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression of concordance with surveillance guidelines for each test was performed using the predictor variables described above. Variables were included in the multivariate analysis if they were significant at a 95% level in the univariate analysis. As a single exception, cancer site was forwarded to multivariate analysis because of its clinical importance. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 250 patients met the study eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are outlined in Table A3 (online only). The median age was 70 years, with approximately two thirds diagnosed with colon cancer and fairly equal numbers with stage II and III cancers.

Colonoscopy

Two hundred one (80.4%) of 250 individuals in the cohort met the guideline; predictors of guideline concordance are shown in Table 1. In multivariate analysis, concordance was positively associated with annual contact with a surgeon (OR = 6.90; 95% CI, 2.44 to 19.54), higher income (OR = 3.23; 95% CI, 1.51 to 6.89), and a diagnosis of colon rather than rectal cancer (OR = 2.62; 95% CI, 1.23 to 5.56). Adherence was lower in those older than 70 (OR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.79) and in those with higher comorbidity (OR = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.83). In this cohort, 89% of colonoscopies were performed by surgeons.

Table 1.

Guideline Concordance: Colonoscopy*

| Characteristic | Meets or Exceeds |

Does Not Meet |

Univariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Multivariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| < 70 | 109 | 87.9 | 15 | 12.1 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| ≥ 70 | 92 | 73.0 | 34 | 27.0 | 0.37 | 0.19 to 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.18 to 0.79 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 109 | 82.6 | 23 | 17.4 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Female | 92 | 78.0 | 26 | 22.0 | 0.75 | 0.40 to 1.40 | ||

| Residential location | ||||||||

| Rest of Manitoba | 82 | 84.5 | 15 | 15.5 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Winnipeg | 119 | 77.8 | 34 | 22.2 | 0.64 | 0.33 to 1.25 | ||

| Income† | ||||||||

| Low | 35 | 61.4 | 22 | 38.6 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| High | 166 | 86.0 | 27 | 14.0 | 3.86 | 1.98 to 7.56 | 3.23 | 1.51 to 6.89 |

| Cancer site | ||||||||

| Rectum | 61 | 73.5 | 22 | 26.5 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Colon | 140 | 83.8 | 27 | 16.2 | 1.87 | 0.99 to 3.54 | 2.62 | 1.23 to 5.56 |

| Collaborative stage | ||||||||

| III | 93 | 78.2 | 26 | 21.8 | 1 | Ref | ||

| II | 108 | 82.4 | 23 | 17.6 | 1.31 | 0.70 to 2.45 | ||

| Comorbidity score‡ | ||||||||

| Low | 103 | 87.3 | 15 | 12.7 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| High | 98 | 74.2 | 34 | 25.8 | 0.42 | 0.22 to 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.18 to 0.83 |

| Chemotherapy treatment | ||||||||

| No | 80 | 76.2 | 25 | 23.8 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 121 | 83.4 | 24 | 16.6 | 1.58 | 0.84 to 2.95 | ||

| Radiation treatment | ||||||||

| No | 158 | 80.2 | 39 | 19.8 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 43 | 81.1 | 10 | 18.9 | 1.06 | 0.49 to 2.30 | ||

| Oncologist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 110 | 74.3 | 38 | 25.7 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 91 | 89.2 | 11 | 10.8 | 2.86 | 1.38 to 5.91 | 1.89 | 0.84 to 4.24 |

| Surgeon contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 119 | 73.0 | 44 | 27.0 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 82 | 94.3 | — | 5.7 | 6.06 | 2.31 to 15.90 | 6.90 | 2.44 to 19.54 |

| Internist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 179 | 79.6 | 46 | 20.4 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 22 | 88.0 | — | 12.0 | 1.88 | 0.54 to 6.57 | ||

| FP/GP contact‖ | ||||||||

| Low | 132 | 78.1 | 37 | 21.9 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 69 | 85.2 | 12 | 14.8 | 1.61 | 0.79 to 3.29 | ||

NOTE. Bold type indicates statistically significant odds ratio and 95% CI. Dashes indicate cell has been suppressed because its size is less than 5.

Abbreviations: FP, family practitioner; GP, general practitioner; Ref, reference.

The guideline is one or more colonoscopies performed at any point in the 3-year period starting with the 7th month after diagnosis.

Measured by income quintile [(from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest)]. Defined as low if income quintile = 1; otherwise high.

Measured by the number of the Major Adjusted Diagnostic Groups counts (range 0-6). Low if count = 0 or 1; otherwise high.

At least 1 visit with a physician of this specialty in each and every year during the study period.

High FP contact signifies an annual number of visits to FPs that is above the median for the cohort in each and every year during the study period; otherwise low.

Liver Imaging

Analysis of guideline concordance is reported in Table 2 and was limited to 163 individuals living in the two largest cities. For this test 77 (47.2%) of 163 patients met the guideline. In the multivariate analysis, three variables were associated with higher concordance: contact with an oncologist (OR = 4.74; 95% CI, 2.28 to 9.88), receipt of chemotherapy (OR = 3.45; 95% CI, 1.48 to 8.05), and diagnosis of colon cancer (OR = 3.15; 95% CI, 1.39 to 7.12).

Table 2.

Guideline Concordance: Liver Imaging*

| Characteristic | Meets or Exceeds |

Does Not Meet |

Univariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Multivariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| < 70 | 45 | 56.3 | 35 | 43.8 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| ≥ 70 | 32 | 38.6 | 51 | 61.4 | 0.49 | 0.26 to 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.38 to 1.73 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 39 | 47 | 44 | 53 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Female | 38 | 47.5 | 42 | 52.5 | 1.02 | 0.55 to 1.89 | ||

| Income† | ||||||||

| Low | 15 | 37.5 | 25 | 62.5 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 62 | 50.4 | 61 | 49.6 | 1.69 | 0.82 to 3.52 | ||

| Cancer site | ||||||||

| Rectum | 19 | 34.5 | 36 | 65.5 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Colon | 58 | 53.7 | 50 | 46.3 | 2.20 | 1.12 to 4.30 | 3.15 | 1.39 to 7.12 |

| Collaborative stage | ||||||||

| III | 46 | 56.1 | 36 | 43.9 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| II | 31 | 38.3 | 50 | 61.7 | 0.49 | 0.26 to 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.30 to 1.39 |

| Comorbidity score‡ | ||||||||

| Low | 41 | 50 | 41 | 50 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 36 | 44.4 | 45 | 55.6 | 0.80 | 0.43 to 1.48 | ||

| Chemotherapy treatment | ||||||||

| No | 19 | 27.5 | 50 | 72.5 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 58 | 61.7 | 36 | 38.3 | 4.24 | 2.16 to 8.30 | 3.45 | 1.48 to 8.05 |

| Radiation treatment | ||||||||

| No | 60 | 48.0 | 65 | 52.0 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 17 | 44.7 | 21 | 55.3 | 0.88 | 0.42 to 1.82 | ||

| Oncologist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 22 | 26.5 | 61 | 73.5 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 55 | 68.8 | 25 | 31.3 | 6.10 | 3.09 to 12.03 | 4.74 | 2.28 to 9.88 |

| Surgeon contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 50 | 47.2 | 56 | 52.8 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 27 | 47.4 | 30 | 52.6 | 1.01 | 0.53 to 1.92 | ||

| Internist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 69 | 47.9 | 75 | 52.1 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 8 | 42.1 | 11 | 57.9 | 0.79 | 0.30 to 2.08 | ||

| FP/GP contact‖ | ||||||||

| Low | 56 | 45.9 | 66 | 54.1 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 21 | 51.2 | 20 | 48.8 | 1.24 | 0.61 to 2.51 | ||

NOTE. Bold type indicates statistically significant odds ratio and 95% CI.

Abbreviations: FP, family practitioner; GP, general practitioner; Ref, reference.

The guideline is one or more computed tomography, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the abdomen performed in each and every 1-year interval starting with the 7th month after diagnosis. Analysis is restricted to the Winnipeg and Brandon Regional Health Authorities, the province's two largest urban areas comprising 64% of the population.

Measured by income quintile [from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest)]. Defined as low if income quintile = 1; otherwise high.

Measured by the number of the Major Adjusted Diagnostic Groups counts (range 0-6). Defined as low if count = 0 or 1; otherwise high.

At least one visit with a physician of this specialty in each and every year during the study period.

High FP contact signifies an annual number of visits to FPs that is above the median for the cohort in each and every year during the study period; otherwise low.

CEA Testing

The analysis of guideline concordance is shown in Table 3. Overall concordance was observed in 55 (22.0%) of 250 cohort members at the standard of three or more tests per year. At the lower standard of two or more tests per year chosen in other studies,12,13 44% of the cohort met the standard. In multivariate analysis, guideline concordance was better in those with annual contact with an oncologist (OR = 3.18; 95% CI, 1.45 to 6.99) and with higher levels of contact with FPs (OR = 2.71; 95% CI, 1.32 to 5.58). Adherence was lower in patients who resided in Winnipeg rather than rural areas (OR = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.57), in those older than 70 (OR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.78), and in those with lower stage disease (OR = 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.80).

Table 3.

Guideline Concordance: CEA Testing*

| Characteristic | Meets or Exceeds |

Does Not Meet |

Univariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Multivariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| < 70 | 38 | 30.6 | 86 | 69.4 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| ≥ 70 | 17 | 13.5 | 109 | 86.5 | 0.35 | 0.19 to 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.18 to 0.78 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 31 | 23.5 | 101 | 76.5 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Female | 24 | 20.3 | 94 | 79.7 | 0.83 | 0.46 to 1.52 | ||

| Residential location | ||||||||

| Rest of Manitoba | 31 | 32 | 66 | 68 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Winnipeg | 24 | 15.7 | 129 | 84.3 | 0.4 | 0.22 to 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.12 to 0.57 |

| Income† | ||||||||

| Low | 8 | 14 | 49 | 86 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 47 | 24.4 | 146 | 75.6 | 1.97 | 0.87 to 4.46 | ||

| Cancer site | ||||||||

| Rectum | 14 | 16.9 | 69 | 83.1 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Colon | 41 | 24.6 | 126 | 75.4 | 1.6 | 0.82 to 3.15 | 2.16 | 0.99 to 4.72 |

| Collaborative stage | ||||||||

| III | 37 | 31.1 | 82 | 68.9 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| II | 18 | 13.7 | 113 | 86.3 | 0.35 | 0.19 to 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.18 to 0.80 |

| Comorbidity score‡ | ||||||||

| Low | 27 | 22.9 | 91 | 77.1 | 1 | Ref | ||

| High | 28 | 21.2 | 104 | 78.8 | 0.91 | 0.50 to 1.65 | ||

| Chemotherapy treatment | ||||||||

| No | 12 | 11.4 | 93 | 88.6 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 43 | 29.7 | 102 | 70.3 | 3.27 | 1.62 to 6.57 | 1.69 | 0.73 to 3.91 |

| Radiation treatment | ||||||||

| No | 44 | 22.3 | 153 | 77.7 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 11 | 20.8 | 42 | 79.2 | 0.91 | 0.43 to 1.92 | ||

| Oncologist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 24 | 16.2 | 124 | 83.8 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 31 | 30.4 | 71 | 69.6 | 2.26 | 1.23 to 4.14 | 3.18 | 1.45 to 6.99 |

| Surgeon contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 34 | 20.9 | 129 | 79.1 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 21 | 24.1 | 66 | 75.9 | 1.21 | 0.65 to 2.24 | ||

| Internist contact§ | ||||||||

| No | 53 | 23.6 | 172 | 76.4 | 1 | Ref | ||

| Yes | — | 8.0 | 23 | 92.0 | 0.28 | 0.06 to 1.24 | ||

| FP/GP contact‖ | ||||||||

| Low | 28 | 16.6 | 141 | 83.4 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref |

| High | 27 | 33.3 | 54 | 66.7 | 2.52 | 1.36 to 4.66 | 2.71 | 1.32 to 5.58 |

NOTE. Bold type indicates statistically significant odds ratio and 95% CI. Dash indicates cell has been suppressed because its size is less than 5.

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; FP, family practitioner; GP, general practitioner; Ref, reference.

The guideline is three tests or more performed in each and every 1-year interval starting with the 7th month after diagnosis.

Measured by income quintile [from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest)]. Defined as low if income quintile = 1; otherwise high.

Measured by the number of the Major Adjusted Diagnostic Groups counts (range 0-6). Defined as low if count = 0 or 1; otherwise high.

At least one visit with a physician of this specialty in each and every year during the study period.

High FP contact signifies an annual number of visits to FPs that is above the median for the cohort in each and every year during the study period; otherwise low.

All Tests Combined

Only 20 (12.3%) of 163 in the smaller cohort for whom liver imaging data were available were concordant with guidelines for all three tests over the follow-up period. As a result of the small numbers, only univariate analysis was performed. Younger age (P = .02) and high levels of FP contact (P = .03) were significant predictors.

Died During Follow-Up

The 97 patients who died between 6 and 42 months of follow-up (excluding those who died within 6 months of diagnosis) were more likely to have stage III disease (P = .017), to be older than 70 years (P < .001), and to have more than one comorbidity (P = .016). Approximately two thirds (66%) of deaths were due to lower GI cancer. Year-by-year concordance with follow-up guidelines for liver imaging and CEA testing did not differ between those who received only 1 or 2 years of follow-up care before death and those who were alive at 42 months (Table A4, online only).

Discussion

Strong health-related administrative datasets in Manitoba, Canada have facilitated an innovative examination of concordance with follow-up guidelines at a population level for a cohort of 250 patients with CRC. We found that concordance with colonoscopy guidelines over 3 years of follow-up is relatively high but is much lower for liver imaging and particularly for CEA testing. Only 12.3% of patients were concordant for all three tests over 3 years. This pattern of concordance is similar to that of other published studies, allowing for the slightly different frequency of suggested testing adopted in each (Table A2). The success of implementation of clinical practice guidelines reflects a complex interaction of patient-, provider-, practice-, and policy-level factors.27,28 Possible drivers of low concordance with CRC surveillance testing include lack of physician belief that early detection of recurrence improves survival,29unclear or unfamiliar guidelines, and lack of clarity regarding which provider is responsible for ordering follow-up tests.13

The profile described here of patient, tumor, treatment, and physician factors that predict guideline concordance for each test is comprehensive and has important implications for care. Younger, healthier, and higher income patients with regular contact with a surgeon were more likely to have received at least one colonoscopy, similar to findings from other studies.12,30 Given the potential morbidity associated with colonoscopy, the first two predictors are not surprising, but the effect of income on concordance is notable in a health system with minimal financial impediments to such testing. Patients with regular contact with a surgeon, who performed almost 90% of the colonoscopies in this cohort, were six times as likely to have had at least one colonoscopy. This potent effect has, to our knowledge, not been previously demonstrated and suggests the importance of ensuring ongoing involvement by the physician performing endoscopy in the organization of follow-up care.

Performance of diagnostic imaging of the liver appears to be driven most strongly by engagement with oncologists and receipt of chemotherapy. High rates of abdominal computed tomography scanning have been demonstrated in Canadian oncology hospitals even before the endorsement of this test in the 2005 ASCO guidelines.13,14 CEA test performance showed a similar relationship, with regular oncologist contact being associated with a three-fold greater likelihood of adherence. However, even for patients in regular contact with an oncologist, concordance rates of 68.8% for liver imaging and 30.4% for CEA over 3 years of follow-up fell well below the guideline.

One of the striking themes of these data was the lower concordance in patients with rectal cancer compared to those with colon cancer. This relative disadvantage is a surprising one, given the additional risk of local recurrence with rectal cancer and its longer, multimodal treatment, and needs to be explored further in other jurisdictions. The greater number of physician specialties involved in rectal cancer treatment may lead to less clarity regarding who is responsible for follow-up testing.13 In contrast to our findings, Cooper et al12 detected no difference for colonoscopy and a significant difference in CEA testing that favored rectal cancer.

Patients with earlier stage disease also appear to be at a disadvantage during surveillance and may require special attention. Stage II patients make up 43% to 60% of patients in the randomized trials of CRC follow-up,3 but their relatively lower rate of relapse31may translate into less attention to follow-up testing by physicians.30,32 Patients in this cohort with stage II disease also were less likely than stage III patients to be referred to an oncologist (70% v 86%) and to receive chemotherapy (36% v 61%),33 which may predispose for less organized surveillance.

The strong positive association between both rural residence and higher levels of FP contact and concordance with CEA test guidelines is a surprising finding. It is at odds with a recent chart review that demonstrated only 7.2% adherence to CEA follow-up testing for patients monitored in primary care in northern Alberta, Canada.15 The beneficial effect of higher levels of FP contact reported here may be unique to rural residents, but further research is required to establish a differential effect of FP contact in rural or urban areas.

This study has several limitations. First, it reflects experience in one Canadian province, and the relatively small cohort of individuals may have limited the power of our analysis. Second, we examined those alive at 42 months, a portion of whom were likely living with recurrence and for whom intensive follow-up was therefore no longer appropriate. However, this is not likely to have led to an underestimation of guideline concordance, as liver imaging and CEA tests are also used in the management of metastatic disease. Guideline concordance rates of those who died during follow-up did not differ from rates among survivors, suggesting that this choice of sample did not introduce any systematic bias in our findings. Third, the follow-up period started at the end of the 6th month after diagnosis for all patients, which represented a middle ground in a cohort where not all patients received adjuvant therapies. Calculating individual completion dates for treatment would be a preferable approach for assessing CEA testing, which is not recommended during fluorouracil-based chemotherapy, but was not possible. Fourth, examining cohorts in subsequent years may show improved concordance because of more opportunity for guideline uptake, although such a pattern is not always demonstrated.34 Fifth, a certain degree on nonconcordance may reflect appropriate care of individuals considered too ill for further curative-intent surgery. Last, health services research of this sort can address neither the physician and patient beliefs and behaviors nor the systemic factors that may be at play in influencing test performance.

In this population-based study, we have demonstrated low levels of concordance with important components of the guidelines for intensive surveillance of patients with CRC after treatment. This “care gap” is of concern given the evidence of improved survival of patients who are monitored closely. Although regular oncologist contact generally predicted better concordance, this still fell well short of the guidelines. Future research needs to focus on assessing interventions designed to improve adherence to follow-up testing, whatever the setting of care. Some approaches advocated include patient-held follow-up care schedules,13 specialized nurse- or physician-led CRC follow-up clinics,35–37 “survivorship care plans” provided to patients and community physicians,38,39 cancer center-based coordination of follow-up care in primary care,15 and the use of reminders generated within electronic medical records.40,41 Survivorship care is an increasing priority within the cancer system. Supporting colorectal cancer patients and their providers in staying on track with recommended follow-up testing is a critical part of helping patients regain their health and stay well after treatment.

Acknowledgment

Supported by a New Emerging Team grant provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and CancerCare Manitoba, and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/CancerCare Manitoba Team in Primary Care Oncology Research: Jennifer Baker, Yvonne Block, Sid Chapnick, Joanne Chateau, Kathleen Clouston, PhD, Habtu Demsas, MD, Herold Driedger, Jeanette Edwards, Melissa Fuerst, Marion Harrison, Duane Hartley, MD, Scott Kirk, Gerald Konrad, MD, Yatish Kotecha, MD, Michelle Lobchuk, PhD, Susan McClement, PhD, Paul Nyhof, Sunil Patel, MD, Diane Stolar, Karen Toews, MD, and Cornelius Woelk, MD.

H.S. is supported in part by an American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Grant. P.M. holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Public Health Agency of Canada Applied Public Health Chair (2008-2013).

An expert panel advised on appropriate standards for follow-up testing for the study: Gerald Konrad, MD, CCFP, Ralph Wong, BSc, MD, FRCPC, Marianne Krahn, MD, FRCPC, Ross Stimpson, MD, FRCSC, Steven Latosinsky, MD, MSc, FRCSC, and Joel Gingerich, MD, FRCPC, of the University of Manitoba. Alun Carter and Craig Bauman of Diagnostic Services of Manitoba assisted in securing laboratory data. Joanne Chateau coordinated the research process for our team, and Kristen Steidl and Irina Vasilyeva served as research assistants.

Presented as a poster at the ASCO Annual Meeting, May 30-June 4, 2010, Chicago, IL (abstr 6079), and at the 2010 Cancer Research in Primary Care International Meeting, May 13-14, 2010, Toronto, Canada.

The results and conclusions presented are those of the authors. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health is intended or should be inferred.

Appendix

Overtesting

The provision of surveillance testing beyond what is recommended by guidelines is also of concern, particularly with procedures that are costly or expose the patient to risk. In this cohort, three or more colonoscopies were performed on 35 (13.6%) of 250 patients of the entire cohort over the 3-year follow-up period. Over the same period, 17 (10.4%) of 163 patients had two or more liver imaging tests, and 11 (4.4%) of 250 had five or more CEA tests performed annually.

Table A1.

Selected CRC Surveillance Guidelines (follow-up years 1-3)

| Sponsor | CEA Test | Liver Imaging | Colonoscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Society of Clinical Oncology5 | Every 3 months for 3 years | Annually for 3 years: CT of abdomen, chest (+ pelvis for rectal cancer), | Pre- or perioperative, then in 3 years, then every 5 years if normal |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network6 | Every 3-6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months | Annually for 3 years: CT of abdomen and pelvis | Pre- or perioperative, then in 1 year, then as clinically indicated |

| CancerCare Ontario7 | At least every 6 months for 3 years | At least every 6 months for 3 years: liver ultrasound | Pre- or perioperative, then in 3-5 years if normal |

| British Columbia Cancer Agency8 | Every 3 months for 3 years | Every 6 months for 3 years | Pre- or perioperative, then every 3-6 years |

| CancerCare Manitoba9 | Every 3 months for 3 years | Annually for 3 years: CT of abdomen, chest (+ pelvis for rectal cancer) | Pre- or perioperative, then in 1 year, then in 3 years, then every 5 years if normal |

NOTE. These guidelines apply to patients well enough to be eligible for curative-intent surgery if recurrence is detected.

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRC, colorectal cancer; CT, computed tomography.

Table A2.

Reported Guideline Concordance for CRC Surveillance Testing

| Source | Colonoscopy (%) | Liver Imaging (%) | CEA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper et al12 | 73.6* | — | 46.7§ |

| Cardella et al13 | 94† | 62‡ | 49§ |

| Cheung et al14 | 85.2-96.9† | — | 59-71‖ |

| Spratlin et al15 | — | — | 7.2¶ |

NOTE. Dashes indicate that the test was not assessed in this study.

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Standard used was one or more colonoscopies in 3 years.

Standard used was one or more colonoscopies in 5 years.

Standard used was two or more scans/year for 3 years.

Standard used was two or more tests/year for 3 years.

Standard used was eight or more tests in 5 years.

Standard used was three or more tests/year for 2 years.

Table A3.

Patient Characteristics (N = 250)

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| < 70 | 124 | 49.6 |

| ≥ 70 | 126 | 50.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 132 | 52.8 |

| Female | 118 | 47.2 |

| Residential location | ||

| Rest of Manitoba | 97 | 38.8 |

| Winnipeg | 153 | 61.2 |

| Income quintile | ||

| 1 (poorest) | 57 | 22.8 |

| 2 | 48 | 19.2 |

| 3 | 54 | 21.6 |

| 4 | 45 | 18.0 |

| 5 (wealthiest) | 46 | 18.4 |

| Comorbidity score* | ||

| 0 | 38 | 15.2 |

| 1 | 80 | 32.0 |

| 2 | 63 | 25.2 |

| 3 | 47 | 18.8 |

| 4 and above | 22 | 8.8 |

| Cancer site | ||

| Rectum | 83 | 33.2 |

| Colon | 167 | 66.8 |

| Collaborative stage | ||

| III | 119 | 47.6 |

| II | 131 | 52.4 |

| Chemotherapy treatment | ||

| No | 105 | 42.0 |

| Yes | 145 | 58.0 |

| Radiation treatment† | ||

| No | 30 | 36.1 |

| Yes | 53 | 63.9 |

Measured by number of the Major Adjusted Diagnostic Groups counts (range 0-6).

Patients with rectal cancer only.

Table A4.

Annual Guideline Concordance Rates for Those Who Died During Follow-Up Versus 42-Month Survivors

| Group | Year 1: 6-18 Months (%) | Year 2: 19-30 Months (%) | Year 3: 31-42 Months (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver imaging | |||

| Died 18-30 months (n = 22) | 81.8 * | — | — |

| Died 30-42 months (n = 22) | 54.6 | 68.2 | — |

| Alive at 42 months (n = 163) | 71.8 | 68.1 | 58.9 |

| CEA testing | |||

| Died 18-30 months (n = 33) | 57.6 | — | — |

| Died 30-42 months (n = 34) | 44.1 | 29.4 | — |

| Alive at 42 months (n = 250) | 59.2 | 37.2 | 32.8 |

NOTE. All time periods begin from the date of diagnosis. Dashes indicate no data as these individuals died during or before this follow-up year.

Abbreviation: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

All within-year comparisons in the table are not statistically significant (P > .10).

Figure A1.

Definition of the study cohort.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Jeffrey Sisler, Bosu Seo, Alan Katz, Daniel Chateau, Piotr M. Czaykowski, Harminder Singh, Donna Turner, Patricia Martens

Collection and assembly of data: Jeffrey Sisler, Bosu Seo, Emma Shu

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeffrey Sisler, Bosu Seo, Alan Katz, Emma Shu, Daniel Chateau, Piotr M. Czaykowski, Harminder Singh, Donna Turner, Patricia Martens

Manuscript writing: Jeffrey Sisler, Bosu Seo, Alan Katz, Daniel Chateau, Piotr M. Czaykowski, Debrah Ann Wirtzfeld, Harminder Singh, Patricia Martens

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Rodríguez-Moranta F, Sal ó J, Arcusa A, et al. Postoperative surveillance in patients with colorectal cancer who have undergone curative resection: A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:386–393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figueredo A, Rumble RB, Maroun J, et al. Follow-up of patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: A practice guideline. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN. Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD002200. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002200.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renehan AG, Egger M, Saunders MP, et al. Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2002;324:813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Colon Cancer Version 3. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Figueredo A, Rumble RB, Maroun J, et al. Practice Guideline Report #2-9. Toronto, Canada: 2004. Follow-Up of Patients With Curatively Resected Colorectal Cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BC Cancer Agency. Cancer Management Guidelines: Follow-up. www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/CancerManagementGuidelines/Gastrointestinal/05.Colon/Management/5FU.htm.

- 9.CancerCare Manitoba. ColonCheck: Screening, Surveillance and Follow Up Recommendations. www.cancercare.mb.ca/home/health_care_professionals/screening/colorectal_cancer_screening/

- 10.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, et al. Getting research findings into practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317:465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, et al. No magic bullets: A systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Reynolds HL., Jr Receipt of guideline-recommended follow-up in older colorectal cancer survivors: A population-based analysis. Cancer. 2008;113:2029–2037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardella J, Coburn NG, Gagliardi A, et al. Compliance, attitudes and barriers to post-operative colorectal cancer follow-up. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung WY, Pond GR, Rother M, et al. Adherence to surveillance guidelines after curative resection for stage II/III colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:191–196. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spratlin JL, Hui D, Hanson J, et al. Community compliance with carcinoembryonic antigen: Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:118–125. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics Canada. Census 2006. www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/rt-td/index-eng.cfm.

- 17.CancerCare Manitoba. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: CancerCare Manitoba; 2008. 2007-2008 Progress Report. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Joint Committee on Cancer. New York, NY: American Joint Committee on Cancer; 2010. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh H, Turner D, Xue L, et al. Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a negative colonoscopy examination: Evidence for a 10-year interval between colonoscopies. JAMA. 2006;295:2366–2373. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen VW, Wu XC. Incidence. In: Andrews PA, editor. Cancer in North America, 1991-1995. Sacramento, CA: North American Association of Cancer Registries; 1999. pp. 1–255. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos LL, Brownell M, Lix L, et al. From health research to social research: Privacy, methods, approaches. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roos LL, Gupta S, Soodeen R, et al. Data quality in an information-rich environment: Canada as an example. Can J Aging. 24(suppl 1):153–170. doi: 10.1353/cja.2005.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Giudice ME, et al. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:174–181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy K, Fradette K, Gheorghe R, et al. The impact of margin status on local recurrence following breast conserving therapy for invasive carcinoma in Manitoba. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:399–402. doi: 10.1002/jso.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finlayson G, Leslie W, MacWilliam L. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health; 2004. Diagnostic imaging data in Manitoba: Assessment and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2008. The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Version 8.0 Release Notes. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, et al. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101(suppl 5):1188–1200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis S, Abidi S, Cox J. Generating personalised cardiovascular risk management educational interventions linking SCORE and behaviour change. J Inf Technol Healthcare. 2008;6:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Earle CC, Grunfeld E, Coyle D, et al. Cancer physicians' attitudes toward colorectal cancer follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:400–405. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossmann I, de Bock GH, van de Velde CJ, et al. Results of a national survey among Dutch surgeons treating patients with colorectal carcinoma: Current opinion about follow-up, treatment of metastasis, and reasons to revise follow-up practice. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:787–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macdonald JS. Adjuvant therapy of colon cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:202–219. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giordano P, Efron J, Vernava AM, 3rd, et al. Strategies of follow-up for colorectal cancer: A survey of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s10151-006-0280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reference deleted.

- 34.Latosinsky S, Fradette K, Lix L, et al. Canadian breast cancer guidelines: Have they made a difference? CMAJ. 2007;176:771–776. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheah LP, Hemingway DM. Improving colorectal cancer follow-up: The dedicated single-visit colorectal cancer follow-up clinic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:260–262. doi: 10.1308/003588402320439694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson S, Sloan K. Patient satisfaction with colorectal cancer follow-up system: An audit. Br J Nurs. 2009;18:40–44. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.1.32089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knowles G, Sherwood L, Dunlop MG, et al. Developing and piloting a nurse-led model of follow-up in the multidisciplinary management of colorectal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;11:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.10.007. discussion 224-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: Treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010 doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:641–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sequist TD, Gandhi TK, Karson AS, et al. A randomized trial of electronic clinical reminders to improve quality of care for diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:431–437. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]