Abstract

Public health interventions are complex in nature and composed of multiple components. Evaluation of process and impact is necessary to build evidence of effectiveness. Process evaluation involves monitoring extent of implementation and comparison against the program plan. This article describes the process evaluation of the ‘Qaderoon’ (We are Capable) intervention; a community-based mental health promotion intervention for children living in a Palestinian refugee camp of Beirut, Lebanon. The manuscript describes the context of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, the intervention, the process evaluation plan and results. The process evaluation was guided by the literature and by a Community Youth Committee. Findings indicated that attendance was 54 and 38% for summer and fall sessions, respectively. Session objectives and activities were commonly achieved. Over 78.4% of activities were reported to be implemented fully as planned. Over 90% of the children indicated high satisfaction with the sessions. Contextual facilitators and challenges to implementing the intervention are discussed. The most challenging were maintaining attendance and the actual implementation of the process evaluation plan. Findings from process evaluation will strengthen interpretation of impact evaluation results.

Introduction

Public health interventions are complex in nature as they are often composed of multiple components [1]. Robust evaluation is thus necessary to build evidence of effectiveness. Implementation or process evaluation involves monitoring and documentation of extent of implementation and comparison against the original program plan. Process evaluation provides feedback on the quality of the intervention; identifies problems, solutions, circumstances under which implementation will succeed; increases knowledge of what components/activities contribute to the outcomes achieved and allows for changes to be made during the intervention [2, 3].

The knowledge base on methods and tools for process evaluation has expanded and been greatly informed by large-scale community intervention conducted in the 1980s and 1990s [4–7]. Based on these trials, a framework for designing and implementing process interventions in public health has been proposed [2]. The basic elements of a comprehensive process evaluation include fidelity, dose delivered, dose received, reach, recruitment and context. Tools used in process evaluation include quantitative and/or qualitative methods such as surveys, log sheets, checklists, observation tools, interviews, focus group discussions and others [8].

Although there have been several peer reviewed manuscripts globally that have documented implementation and process evaluations, none have done so, to our knowledge, in the Eastern Mediterranean region nor with refugees. This paper will describe the process evaluation of the ‘Qaderoon’ (We are Capable) intervention, a community-based mental health promotion intervention for children living in a Palestinian refugee camp of Beirut. This paper is one in a series of papers documenting various phases of the evaluation research of this intervention [9–12].

Context

The Burj El Barajneh Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon (BBC), is the 6th largest of the 12 official camps established in Lebanon to house Palestinian refugees after 1948 [13]. BBC houses approximately 14 000–18 000 residents over an area of 1.6 km2 [13]. Palestinian refugees in Lebanon live under dire environmental and social conditions. These conditions are commonly perceived to be the worst of Palestinian refugees in the region, due to limited employment opportunities, scarce economic resources and limited access to basic health and social services [14].

Health and social services are provided by a variety of international as well as governmental and non-governmental organizations. The United Nations Refugee and Works Agency (UNRWA) was set up in 1948 specifically to provide educational and health services to the Palestinian refugees. However, the population in the camp has been expanding since 1948 with little expansion in the number of schools. As a result, classrooms are crowded, and children attend school in double shifts: the boys in the morning 1 month and in the afternoon another and the girls the reverse.

The intervention

‘Qaderoon’ (We Are Capable) was a year-long social skill building intervention for children (11–14 years), their parents and teachers aimed at promoting mental health of refugee children and increasing their attachment to school. The evidence-informed intervention aimed to achieve these outcomes through changing intermediate outcomes such as communication skills, problem-solving skills, relationship with parents and teachers, among others [11].

The overall frameworks guiding the intervention were (i) the ecologic approach [15] through emphasis on children, their parents and their teachers and (ii) community-based participatory research (CBPR) [16, 17] to enhance relevance, effectiveness and continuity. The ecological framework posits that when developing interventions aiming at behavioral change, interpersonal, organization, community and public policy factors need to be considered. CBPR is ‘a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action’. The planning, implementation and evaluation phases of ‘Qaderoon’ were guided by a local coalition, the ‘Community Youth Coalition’ (CYC), established for this project. The CYC is a grass roots coalition composed of 17 Non-Governmental Associations (NGOs) that work with youth in the Burj Camp, funders of projects in the camp, representatives of the UNRWA, community residents, youth and the research team from the American University of Beirut. The intervention consisted of 45 sessions with children, 15 sessions with parents and 6 workshops with teachers. This paper focuses on the children’s component.

The intervention was informed by three evidence-based interventions [18–20]: stress inoculation training, improving social awareness and social problem solving and positive youth development program. A thorough process of adaptation to context and cultural norms was undertaken by members of the research team and community members from the CYC. The process of adaptation was guided by the research team and included several steps: (i) Review of articles focused on differences between youth of different cultures or on adapting interventions to different populations; (ii) Based on the review, key principles were set for the adaptation of the activities on the manual; (iii) Sessions from each of the evidence-based interventions were reviewed and activities were adapted with the principles in mind; (iv) Two sessions were pretested with youth in the camp and adjustments made as a result; (v) The completed manual was shared with the CYC for feedback; (vi) Ten sessions were pilot tested with youth of the same age group recruited from schools in another camp and changes made accordingly [11].

The final intervention consisted of 35 sessions developed in consultation with the community and 10 developed across the course of the intervention period based on the input from the children themselves regarding topics of interest (Table I). The activities of the 45 sessions were interactive in nature. The children convened in classes set up either with round tables or in semi circles or on the floor to create an atmosphere of trust, to facilitate sharing and to eliminate sense of hierarchy.

Table I.

Outline of intervention sessions

| Sessions |

|---|

| Introduction |

| Session 1: Introducing the program |

| Session 2: Ground rules |

| Session 3: The school |

| Session 4: The school and I |

| Session 5: The family |

| Session 6: The family and I |

| Session 7: The community |

| Session 8: Photovoice |

| Session 9: Tree of determinants |

| Communication |

| Session 10: Resisting peer pressure |

| Session 11: The others and I |

| Session 12: The others and I |

| Session 13: Non-verbal communication |

| Session 14: Healthy communication |

| Self-esteem |

| Session 15: Building self-esteem |

| Session 16: Building self-esteem |

| Self-responsibility |

| Session 17: Self-responsibility I |

| Session 18:Self-responsibility II |

| Social problem solving |

| Session 19: Stop and calm down (introducing the first step toward problem solving) |

| Session 20: Stop and calm down (identifying stress and emotions) |

| Session 21: Think before you act then solve the problem |

| Session 22: Problems with family |

| Session 23: Problems with school |

| Social action project |

| Session 24: Introduction |

| Session 25–35: Social action project—planning, implementation and presentation. |

| Extra sessions developed in response to the felt needs of the youth in the camp |

| Creativity |

| Stereotypes |

| Peer pressure |

| Smoking |

| Self-expression |

| Proper nutrition/fitness/hygiene |

| Controlling use of sharp weapons/violence |

| Art therapy sessions—three in which the youth got to express their feelings toward themselves, their families, their community, their home and their dreams through the use of various art media which included charcoal, cloth, paints and oil pastels |

An intervention manual described each session, its main objectives, the activities to meet the objectives and time allocated for each activity. Process evaluation forms were developed and tailored to each session.

The intervention was conducted out of school hours but within a school premises; on one floor (5 rooms) of one of the schools serving the camp that UNRWA generously provided at no cost. The space was emptied from the usual seating arrangement, repainted and refurbished with round tables and chairs and other needed supplies.

The intervention period stretched from August 2008 till May 2009. It started as a 2-week intensive daily summer intervention (summer phase) and then continued as the academic year on Fridays (a weekend day) and school holidays till May 2009 (fall phase). The six UNRWA schools in the camp having 5th and 6th grade (academic year 2008–2009) were randomly assigned to either intervention or control groups. The intervention group participated in the program. Throughout the intervention, participants were grouped into 10 groups of about 15 children. The research design was quasi-experimental involving a total of six schools randomized into control or intervention [10]. The control group was scheduled to receive a shorter version of the program (15 sessions) at the conclusion of the posttest. Pretest and posttest survey data for both the intervention and control group participants were collected by trained survey administrators.

Intervention implementation team

The ‘implementation team’ consisted of a master trainer, 6 facilitators and 23 youth mentors. The master trainer participated in the adaptation of the intervention, conducted the pilot sessions and was responsible for all aspects of the training of facilitators and youth mentors. The facilitators—recruited based on prior experience working with children of similar age groups—were responsible for implementing the sessions, completing process evaluation forms, supervising the youth mentors and preparing them for the upcoming sessions, as well as documenting changes to the sessions and the reason behind the changes. The youth mentors were all residents of the Burj camp or an adjacent camp and were recruited through the CYC or other NGO’s. The youth mentors assisted the facilitators in all aspects of the sessions and participated in the collection of process evaluation data. They were also the liaison between the facilitators and the children. A field coordinator was recruited from the CYC to handle the logistics of the entire intervention. The field coordinator also maintained a close relationship with the community, the schools and the parents.

Methods—the process evaluation plan

The plan for process evaluation was guided by the literature [8] and developed through a number of meetings and discussions between the CYC and the researchers. The evaluation plan incorporated data collection tools to measure fidelity, dose delivered, dose received (satisfaction) and reach. The overall process evaluation plan included details on data collection method, who was responsible for data collection, and the frequency of collecting data.

Data collection tools

Data collection tools for each session included two observation forms, one evaluation activity with the children and one attendance log sheet (Table II).

Table II.

Plan of process evaluation

| Instrument | Process evaluation component | Frequency of data collection | Evaluator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session observation Form A | Dose delivered, dose received, fidelity (sessions completed as planned) | Every session Sample of sessions based on a schedule | FacilitatorObserver |

| Session observation Form B | Dose received | Every session | Youth mentors |

| Smiley Satisfaction Form C | Dose received | Every session | Youth mentors |

As can be seen in Table II, data were collected by observers (consisting of the research team, community members and Master of Public Health (MPH) students) and the implementation team (consisting of facilitators and youth mentors). The MPH student volunteers and community members were not involved in the day-to-day implementation of the intervention. The facilitators, youth mentors and researchers were either involved in the development of or implementation of the program. However, to encourage accurate reporting, emphasis was given to the fact that the evaluation was not about ‘performance’ but about documentation.

With respect to sessions and groups observed for the process evaluation, 39.0% of groups and sessions had at least one observer. Researchers and facilitators (observing sessions other than their own) observed a total of 98 sessions, students observed 18 sessions and community members observed 13 sessions.

Observation Form A was completed at the end of each session for each group by facilitators and by observers for the sessions and group they observed. Form A measured the extent to which the objectives of the sessions were achieved, tracked implementation of specific activities as per the manual, if each activity was implemented (yes/no) and the extent to which activities and objectives of the sessions were implemented as planned (including time spent on each activity) and included an overall rating of the dynamics of the session (positive and active, positive but not active, not much enthusiasm and negative). This form assisted in measuring dose delivered and one question assessed dose received. Specifically, three questions from this form were relevant: (i) to what extent were the objectives of the sessions met? Response options 0–25, 26–50, 51–75 and 76–100%. We considered the session objectives to be ‘fully’ implemented when the rater checked the 76–100% option; (ii) a question asked whether or not the activities were implemented at all with response options yes/no and (iii) to what extent the activities in the session were implemented as planned—with response options: 0–25, 26–50, 51–75 and 76–100%. We considered the activity to be implemented fully when the rater checked the 76–100% option. This form also helped in tracking dose received. We considered that the session was fully received when the facilitator or observer stated that children were positive and active in the session.

Form A also was used to measure fidelity. For each session, Form A included a table that documented whether each activity was or was not implemented as outlined in the manual. The summative responses across groups and across sessions were used to calculate percent of sessions in which all activities were implemented as planned or in which at least one activity or more than one activity was not implemented as planned. We defined fidelity as all those sessions where all activities were implemented as planned.

Session observation Form B was completed at the end of each session for each group by the youth mentors only (two per group). This form assisted in measuring dose received. Form B tracked number of children who participated actively in the session in terms of discussions, asking questions, participating in activities, etc. This was reported as average active participation rate. Mentors also rated the session, and we considered that the session was fully received when the youth mentors rated the session as positive and active.

Form C measured satisfaction of the children by using happy, neutral or sad faces. At the end of each session for each group, the facilitator would leave the room and the mentors would pass out to children a face upon which the children drew either a smile, a frown or a straight line (neutral). Before starting the satisfaction evaluation exercise, the mentors explained to the children that this exercise was to rate the extent of their satisfaction with the session that day. We created a summary measure for all sessions. The attendance log sheet tracked attendance of every child at each session and as such measured reach.

Data collection tools were pretested during the piloting phase of the intervention and adjustments were made as necessary. One member of the research staff (R.T.N) was assigned as primarily responsible for follow-up of the process evaluation.

Qualitative methods of assessment

In addition to the more quantitative forms described above, a variety of more qualitative methods were used to monitor and assess quality of implementation. These included:

During the intensive summer session, daily meetings were held between the implementation team (facilitators and mentors), the field coordinator, and the research team to discuss the sessions of the day and tackle any potential challenges that arose. Subsequently, once the school year had begun, these meetings became weekly, in the late afternoon after completion of session implementation. We did not take minutes of these meeting but implemented decisions immediately.

Facilitators met on a weekly basis prior to each session to critically review the activities of the session based on previous challenges as well as positive aspects. The intent was to learn from each other and from the previous interactions with the group, as well as to enhance consistency in the implementation of activities across facilitators. No minutes were taken of these meetings, but any changes in activities that were made were documented and led to Version 2 of the manual.

Observers provided comments on their forms of aspects that were positive or needed improvement for both facilitators and mentors. These were documented on the forms.

In light of decreasing attendance, facilitators and mentors carried out home visits to ask parents about reasons for non-attendance of their children. These were documented on forms.

The field coordinator often had discussions with parents when they dropped off their children or when she met them on the streets of the camp about their perceptions of the program. She also observed sessions and provided her insight into aspects that needed to be adjusted based on her knowledge of context.

As mentioned previously, the CYC was established to guide all aspects of the intervention. Meetings with the CYC during the implementation provided opportunity for them to share what they had been hearing about the intervention from parents and children and teachers.

Data collection and analysis

At the end of each day, one of the facilitators collected the day’s forms, including the attendance. These were checked for completion in terms of number of required forms for each group as well as filling of all the information of each form. When gaps were found, they were followed up immediately and the data were updated.

Data were entered on a daily basis by a member of the implementation team who as responsible for ensuring that all process evaluation forms were completed and collected. All statistical analyses were done using SPSS (Version 16). Descriptive statistics including proportions were computed. The research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut.

With regard to the more qualitative data, these resulted in immediate changes to sessions, activities and therefore no further analysis was conducted.

Results

Results of the process evaluation are outlined in Table III and summarized below.

Table III.

Results of the process evaluation of Qaderoon

| Dose delivered | ||||||||

| Activities reported to be implemented as planned, extent reaching 76 to 100%, N (%) | Summer | Fall | ||||||

| Facilitatora | 124 (91.2) | 135 (79.4) | ||||||

| Observera | 27 (81.8) | 43 (71.7) | ||||||

| Objectives reported to be achieved as planned, extent reaching 76 to 100%, N (%) | Summer | Fall | ||||||

| Facilitatora | 122 (93.1) | 136 (79.5) | ||||||

| Observerb | 36 (76.6) | 48 (65.8) | ||||||

| Dose received | ||||||||

| Percent of sessions rated as “positive and active”, N (%) | Summer | Fall | ||||||

| Mentor 1a | 113 (85.6) | 121 (76.1) | ||||||

| Mentor 2a | 100 (81.3) | 102 (79.1) | ||||||

| Facilitatora | 102 (72.9) | 133 (78.7) | ||||||

| Observerb | 27 (77.1) | 50 (66.7) | ||||||

| Average active participation rate (%)c | Summer | Fall | ||||||

| Mentorsa | 89.9 | 86.4 | ||||||

| Fidelity | ||||||||

| Activities fully implemented, N (%) | Overalld | Summer | Fall | |||||

| Facilitatora | 242 (78.3) | 115 (83.9) | 127 (73.8) | |||||

| Observerb | 106 (80.9) | 47 (87.0) | 59 (76.6) | |||||

| At least one activity not implemented, N (%) | Overalld | Summer | Fall | |||||

| Facilitatora | 56 (18.1) | 20 (14.6) | 36 (20.9) | |||||

| Observerb | 18 (13.7) | 6 (11.1) | 12 (15.6) | |||||

| More than one activity not implemented, N (%) | Overalld | Summer | Fall | |||||

| Facilitatora | 11 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 9 (5.2) | |||||

| Observerb | 7 (5.3) | 1 (1.9) | 6 (7.8) | |||||

| Reache | ||||||||

| Attendance N (%) | ||||||||

| Overall groups & sessions | Did not attend any session | <50 % of sessions | 50-69% of sessions | 70-89% of sessions | ≥ 90% of sessions | |||

| 20 (6.7) | 166 (55.5) | 60 (20.1) | 46 (15.4) | 7 (2.3) | ||||

N summer = 144, N fall = 187; total number of evaluations completed by the facilitators and mentors in the summer and fall respectively.

N summer = 54, N fall = 75; total number of evaluations completed by the observers in summer and fall respectively.

% of average active participation: Average of active students as rated by the two evaluating mentors over all the points of observation (groups and sessions).

Overall sessions and groups, throughout the intervention: summer and fall.

N=299 (Total number of youth assigned to intervention).

Dose delivered

For the summer sessions, the percentage of activities implemented (to an extent ranging between 76 and 100%) was reported as 91.2% by facilitators and 81.8% by observers while for the fall sessions, they were reported as 79.4% by facilitators and 71.7% by observers. The percentage of objectives met (to an extent ranging between 76 and 100%) was also favorable as reported by facilitators and observers in both the summer and fall sessions. A separate analysis was done to note if there is a significant difference in reporting by facilitators and observers. The only significant difference was in the summer sessions with facilitators reporting significantly higher percentages of sessions with objectives achieved as planned than the observers (P-value < 0.05). All other percentages reported by facilitators and observers for activities and objectives across summer and fall sessions were not found to be significantly different.

Dose received

For the summer sessions, the percentage of sessions in which children’s participation was rated as ‘positive and active’ was 85.6, 81.3, 72.9 and 77.1% by Mentor 1, Mentor 2, facilitators and observers, respectively. For the fall sessions, the percentage reported by the facilitators increased, whereas for all others, it decreased. Overall average participation rate was 89.9% in the summer and 86.4% in the fall sessions.

Fidelity

Over all the groups and sessions, the facilitators reported 78.3% of activities to be implemented fully. Percentage of activities implemented fully was reported as higher in the summer than in the fall by both facilitators and observers.

In measures of dose delivered, dose received and fidelity, observed differences between facilitators and observers may be due to differential involvement in and engagement with the intervention. Observers as external evaluators may have been able to judge somewhat more objectively than the facilitators who were enmeshed in every detail. The differences however are minor and do not change interpretation of the results.

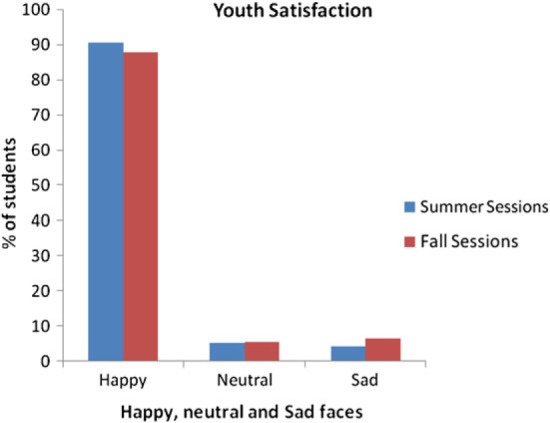

Satisfaction

In the summer session, in all sessions and groups combined, 90.4% of children chose a happy face to express their rating of the session, as opposed to 87.4% in the fall session (Fig. 1). Although this method may be a crude measure of satisfaction, in combination with results from other data, it provides a good indication of general happiness of children with activities.

Fig. 1.

Satisfaction of children with sessions of ‘Qaderoon’.

Reach

Out of all the children randomized to the intervention and who completed the baseline survey (n = 299), 6.7% did not attend any session, 55.5% attended 50% or fewer sessions, 20.1% attended between 50 and 69%, 15.4% attended between 70 and 89% of the sessions and 2.3% attended more than 90% of the sessions.

Qualitative measures

During daily and weekly meetings of the implementation and research team, facilitators and mentors noted the short attention span of children. As a result, we developed an additional manual of energizers and songs for them to use. Facilitators and mentors quickly learned to introduce ‘energizer’ games as needed. These additional activities were reported on the process evaluation sheets. Several issues related to the unique culture and context arose and had to be dealt with such as seating arrangements of girls and boys and specific topics for role plays. The presence of youth mentors greatly facilitated these decisions.

Discussions with the field team and observations by the field coordinator also indicated that ground rules were often not followed. We thus implemented a number of incentives targeted at the children themselves such as a reward system (of stars) for keeping the ground rules; trips for groups that maintained a certain number of stars (we set the target low so almost all children were eligible) and carnival events.

Weekly discussion between facilitators resulted in changes in activities based on experiences to date. These changes are all documented in Version 2 of the intervention manual.

The intervention spanned 9 months (August 08–May 09). Although children were eager to attend each week, their parents were often a barrier. Interviews with parents during home visits indicated that they sometimes did not know when the sessions were being held. They also saw education as a top priority, and good grades as paramount. Parents often saw little ‘educational’ value to ‘Qaderoon’ and therefore preferred to have their children spend the time studying than attending the sessions. A monthly schedule of all sessions and activities was sent home regularly with the children to remind them of the intervention schedule. The research and implementation team took several measures to respond to this challenge. We met with principals of schools and they agreed not to give exams on Saturday (the program took place on Friday, a weekend day). And, English reading sessions were added as an extra activity to increase the perceived educational value of the program.

The discussions that the field coordinator had with parents also indicated reasons for non-attendance: activities of other NGOs. Children and their families often are ‘members’ of NGOs in the camp that may provide them with monetary or in kind support. As such, they feel compelled to attend their activities. We distributed a calendar of our sessions to all NGOs in order to minimize this overlap and negotiated with NGOs to hold activities at times different from those of the ‘Qaderoon’ sessions.

The presence and respect of CYC members in the community created a bridge to understanding and cooperation with parents. Parents would share their feelings about the program with the CYC members who would then vocalize these in meetings of the CYC. These discussions indicated great community support for the ‘Qaderoon’ intervention and perceived impact on social skills of participating children.

Discussion

This paper described the Qaderoon intervention and its process evaluation. To our knowledge, this is the first manuscript to discuss process evaluation of a public health intervention in a refugee camp setting and the first to do so in the Arab world. Overall, process evaluation indicated that session objectives were commonly achieved and that specific session activities were frequently implemented as planned. Children indicated high satisfaction with the sessions. These results will strengthen interpretation of impact evaluation results once analyzed.

Attendance rates in our intervention ranged from 38 to 54%. Despite seeming low, they are similar to other after school programs described in the literature [21–23]. The literature has highlighted that the main limitation of comparing attendance rates across programs and schools is the definition of attendance. In a recent evaluation of the impact of after school programs, Kane [24] found that ‘each of the programs reported participation differently’. For example, some included those who attended a center at least three times during the initial month of operation. Others included those who attended at least one session of an intervention during a school year. Still others reported the proportion of youth ever participating.

With respect to dose delivered, observers of ‘Qaderoon’ indicated that in the summer 87% and in the fall 76% of the intervention activities were delivered. This is also similar or higher than rates reported in the literature [25, 26]. In terms of dose received, we report it as the ratings by facilitators of percent of sessions that were positive and active. ‘Qaderoon’ reported dose received by observers was 77% in the summer and 67% in the fall sessions. Dose received reported in an arts-based intervention in schools (6th graders) was between 36 and 43% [26].

Related to fidelity, our results indicate that overall 79% of the activities were fully implemented. Previous literature has indicated rated between 51 and 93% depending on program component and school grade [27, 28]. Finally, our results indicate that 94% of participants were satisfied with the intervention—a rate higher than that in the literature [29].

The more qualitative monitoring of implementation dealt with immediate problems as they arose, gathered data when applicable, and resulted in changes in structure and content of the intervention. Some similar observations have been found in an intervention in Canada working with disadvantaged Canadian youth. Attendance was low, but satisfaction was high. Transportation was crucial and led to attrition when support staff could not provide transportation. Barriers included issues related to scheduling (starting sessions late), staff changes, youth behavior and inconsistency in agreement on program objectives among implementers. Student non-attendance was related to load of schoolwork, other leisure activities or work commitments [30].

As described in the introduction, in addition to documentation extent of implementation, process evaluation also identifies problems, solutions and circumstances under which implementation will succeed. We describe below facilitators and challenges to implementing the intervention, as well as to implementing the process evaluation plan.

Facilitators to implementation

The quality of implementation was enhanced by several factors. The first was the lengthy process of developing the intervention manual. The manual development spanned approximately 6 months as we adapted evidence-based activities and then shared them with CYC members for contextualization. The ‘Qaderoon’ manual outlined each session in detail starting with its objective and explaining each activity thereafter. Program manuals are acknowledged to be important and are a prerequisite for funding by some institutions [31].

In addition, the implementation team attended intensive training sessions. Cognizant of the fact that fidelity ‘is a function of the intervention providers’ [2], the research team invested effort to recruit the most appropriate facilitators and youth mentors and spent time on extensive training not only on content but also on interaction style, method of implementation and on methods of evaluation.

The commitment of the implementation, research and field team also facilitated implementation. As mentioned previously, the six facilitators met weekly (or daily during intensive weeks) to review the upcoming sessions, dialogue about each activity, and come to consensus on how to approach the session.

Challenges to implementation

The team was large consisting of 6 facilitators and 23 youth mentors. Most of the youth mentors were in school or at university, making scheduling difficult. This challenge was also cited by Lytle et al. [32] with regard to the CATCH trial. However, the cohesiveness of the team and the presence of a field coordinator from the community itself made managing schedules easier. Team members took over from each other whenever possible, and the field coordinator had easy access to the mentors for substitutions whenever changes in schedule happened on short notice. The size of the team also made replicability difficult. Despite the detailed outline of the sessions and the regular meetings of facilitators to share ideas, each facilitator had his/her own style of presenting the material as well as interacting with children. Although there may be impact of different presentation styles on results of the intervention (a Hawthorne-like effect), it is difficult to document the impact of such natural variations in style. The analytic strategy conducted assumed that such variations (some having potential enhanced effects on the intervention and some attenuated effects) would be balanced out in an assessment of the overall effects of the intervention.

Challenges due to intervention context

As with any other context, events in the external environment may affect implementation. In our context, these types of events are rarely trivial, and often of great impact on the very outcomes we are trying to improve. As a pointed example, during the implementation of ‘Qaderoon’, the events of Gaza (December 2008) seriously affected the implementation of our sessions. In what was considered a grave escalation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas—the ruling party in the Gaza strip—Israel attacked the Gaza strip for a period of three consecutive weeks resulting in a high number of Palestinian civilian casualties and tremendous destruction of civilian property and infrastructure. We were just beginning our intensive winter break week as news from Gaza leaked. The children were understandably unable to concentrate and were deeply disturbed by these events. At this juncture, we decided to halt all ‘usual’ activities and focus on allowing the students to express their feelings through art and writing. Political events in Lebanon during the year also impacted our ability to stick to an implementation schedule. A more specific contained event occurred in the first week of implementation of the summer session. The camp streets are very narrow and buildings very close to one another. A person passed away from a home in one of the buildings in the street where we were implementing our intervention. The custom in our region is to have 3 days of mourning. Any loud happy noises coming from the school could definitely be heard at the home of this person and would be perceived to be inappropriate and taint the project at an early stage. We therefore had to tone down the activities of the intervention during those 3 days. Such contextual events are inevitable in any community and are poignant reminder of the interface between research and practice in real-world settings. Researchers should expect such distractions and take them in stride. Any other response risks alienating the community and increasing the gap between researchers and community members.

Challenges in data collection for the process evaluation

Challenges to data collection include the understanding of the importance of process evaluation by the facilitators, youth mentors and observers as well as issues of inability to observe due to time constraints or other commitments related to the project. With respect to the former, data collectors had to consistently be reminded to complete the evaluation forms during the initial stage of intervention implementation. We entered data daily and were therefore able to follow-up with missing data as needed. In the CATCH trial, regular quality checks were deemed necessary to ensure accurate process evaluation data [32]. Eventually, due to the regular follow-up, the implementation team understood the importance of process evaluation.

With respect to the second point, the original plan for process evaluation data collectors also included members of the CYC. This proved difficult due to their time constraints and the necessity of arriving exactly at the beginning of the session or before. In addition, according to members of the CYC, the community also trusted the project and felt that there is no need to be involved in the monitoring. The research team observers often had to disengage from the role of observer to problem solve with difficult children or to tend to a community concern that needed immediate attention. The unavoidable interruptions meant that they were unable to complete the observation of the session.

Another challenge for research team observations were competing academic demands of teaching and administrative work. The researchers were committed to the process evaluation, however, and this resulted in the high percent of observations. In response to this challenge, and to an increasing number of community-based projects, the academic unit where the researchers are based began to consider how to incorporate the extended time needed to build community trust and to engage community members in all phases of research in consideration of time lag to publication.

Several limitations for this process evaluation should be noted. We relied mostly on internal evaluators—with the exception of the observers who observed 39% of overall sessions. Our target for sessions to be observed was 20%. There is a debate in the literature as to whether evaluation should be conducted by internal or external evaluators [31]. Whereas there may be biases with internal evaluators, budget limitations often preclude hiring an external evaluator. We found a combination of both to be effective by triangulating multiple methods of data collection. In addition, for the internal evaluators, we relied on self-report. We also relied on the implementation team to provide data on program reach rather than asking the children themselves. The facilitators regularly checked for comprehension of the terms and skills by ending the session with a 5 min wrap up summary and beginning the next session with a 5 min recall of previous skills.

The value of a process evaluation extends to its significance in understanding, interpreting and validating impact and outcome evaluation results. If the intervention is found to have no impact, then process evaluation findings could be used to explain potential reasons such as low attendance. If the intervention is found to be effective, then process evaluation data can indicate specific aspects that were particularly important and can be used to scale up the intervention with children in other Palestinian camps in Lebanon. For example, reach data could be used to calculate the necessary ‘dose’ of intervention needed to achieve optimal impact. Process evaluation data has also already led to revisions to the intervention manual adjusting activities that were not implemented or implemented differently.

This paper has described the ‘Qaderoon’ intervention and its process evaluation. There are several lessons learned from the implementation of both the intervention and the process evaluation. Perhaps foremost among them is the critical importance of community involvement and relationship building [33]. The CYC’s involvement with every aspect of this project from inception to evaluation created a sense of partnership that smoothed out many wrinkles in implementation. In addition, the willingness of the academic team to listen to and learn from the community built trust and eased tensions. Other lessons learned in implementation include the need to be flexible despite deadlines and to think outside the box when strategizing—especially around community-specific contextual factors. With respect to process evaluation, our experience underscores the importance of looking beyond the quantitative numbers that may identify reach, dose delivered, dose received, satisfaction and fidelity, to the more complex and qualitative indicators of program implementation: the problems, solution and circumstances that define a specific intervention in a specific context. This paper adds to the literature on process evaluation by describing an intervention in the Eastern Mediterranean region, in a disadvantaged community, and with refugee children.

Funding

Wellcome Trust (081915/Z/07/Z).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the community of Burj El Barajneh refugee camp and specifically, the community partners involved in the CYC for their active engagement in all phases of this intervention and its evaluation. We would like to acknowledge UNRWA not only for its participation in the CYC but also for providing the space in the school in which we conducted the intervention as well as the constant collaboration in order to enhance access to and participation of the children. We would also like to thank the field coordinator and implementation team for their dedication and commitment to this program and its evaluation process. The authors would like to thank reviewers for valuable comments that strengthened the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Br Med J. 2000;321:694–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: an overview. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basch CE, Sliepcevich EM, Gold RS, et al. Avoiding type III errors in health education program evaluations: a case study. Health Educ Behav. 1985;12:315–31. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farquhar JW, Fortmann SP, Maccoby N, et al. The Stanford five-city project: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:323–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carleton RA, Lasater TM, Assaf AR, et al. The pawtucket heart health program: community changes in cardiovascular risk factors and projected disease risk. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:777–85. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.6.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finnegan JR, Murray DM, Kurth C, et al. Measuring and tracking education program implementation: the Minnesota Heart Health Program experience. Health Educ Q. 1989;6:77–90. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGraw SA, Stone EJ, Osganian SK, et al. Design of process evaluation within the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) Health Educ Q. 1994;2:5–26. doi: 10.1177/10901981940210s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:134–47. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makhoul J, Alameddine M, Afifi R. “I felt that I was benefiting someone”: youth as agents of change in a refugee community project. Health Educ Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/her/cyr011. doi:10.1093/her/cyr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afifi RA, Nakkash R, El Hajj T, et al. Qaderoon youth mental health promotion programme in the Burj El Barajneh Palestinian refugee camp, Beirut, Lebanon: a community-intervention analysis (abstract) Lancet. 2011, Available at: http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/pdfs/palestine/S0140673610608471.pdf. Accessed: 2 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afifi RA, Makhoul J, El Hajj T, et al. Developing a logic model for youth mental health: participatory research with a refugee community in Beirut. Health Policy Plan. 2011:1–10.. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr001. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdulrahim S, El-Shareef M, Alameddine M, et al. The potential and challenges of an academic-community partnership in a low trust urban context. J Urban Health. 2010;87:1017–20. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9507-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Refugee and Works Agency (UNRWA) Available at: http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/lebanon.html. Accessed: 5 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen LB. Finding Means: UNRWA’s Financial Situation and the Living Conditions of Palestinian Refugees. [Summary Report, FAFO report.] Norway (Oslo): Interface Media; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. “An ecological perspective on health promotion programs”. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence. [Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 99.] Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, et al. Methods in Community–based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kegler MC, Oman RF, Vesely SK, et al. Relationships among youth assets and neighbourhood and community resources. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:380–97. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruene-Butler L, Hampson J, Elias M, et al. Improving social awareness-social problem solving. In: Albee GW, Gullota TP, editors. Primary Prevention Works. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maag JW, Katlash J. Review of stress inoculation training with children and adolescents. Behav Modif. 1994;18:443–369. doi: 10.1177/01454455940184004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane TJ. The Impact of After-School Programs: Interpreting the Results of Four Recent Evaluations. New York, NY: William T. Grant Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durlak JA, Weissberg RP. The Impact of After-School Programs that Promote Personal and Social Skills. Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balsano AB, Phelps E, Theokas C, et al. Patterns of early adolescents’ participation in youth development programs having positive youth development goals. J Res Adolesc. 2009;19:249–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane TJ. The Impact of After-School Programs: Interpreting the Results of Four Recent Evaluations. Available at: www.wtgrantfoundation.org/usr_doc/After-school_paper.pdf. Accessed: 17 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, et al. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: the ACT trial experience. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-79. Available at: http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/pdf/1479-5868-6-79.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gay JL, Corwin S. Perceptions of program quality and fidelity of an arts-based after school program: a process evaluation. Curr Issues Educ [On-line] . 2008;10 Available at: http://cie.ed.asu.edu/volume10/number1/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosecrans AM, Gittelsohn J, Ho LS, et al. Process evaluation of a multi-institutional community-based program for diabetes prevention among First Nations. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:272–86. doi: 10.1093/her/cym031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steckler A, Ethelbah B, Martin CJ, et al. Pathways process evaluation results: a school-based prevention trial to promote healthful diet and physical activity in American Indian third, fourth, and fifth grade students. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pbert L, Osganian SK, Gorak D, et al. A school nurse-delivered adolescent smoking cessation intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2006;43:312–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beaulac J, Olavarria M, Kristjansson E. A community-based hip-hop dance program for youth in a disadvantaged community in Ottawa: implementation findings. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:61S.. doi: 10.1177/1524839909353738. DOI: 10.1177/1524839909353738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mowbary CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, et al. Fidelity criteria: development, measurement, and validation. Am J Eval. 2003;24:315–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lytle LA, Davidann BZ, Bachman K, et al. CATCH: challenge of conducting process evaluation in a multicenter trial. Health Educ Q. 1994;2:129–41. doi: 10.1177/10901981940210s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;17:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]