Abstract

α,β-Unsaturated imides, formylated at the nitrogen atom, comprise a new and valuable family of dienophiles for servicing Diels-Alder reactions. These systems are assembled through extension of recently discovered isonitrile chemistry to the domain of α,β-unsaturated acids. Cycloadditions are facilitated by Et2AlCl, presumably via chelation between the two carbonyl groups of the N-formyl amide. Applications of the isonitrile/Diels-Alder logic to the IMDA reaction, as well as methodologies to modify the N-formyl amide of the resultant cycloaddition product, are described. It is expected that this easily executed chemistry will provide a significant enhancement for application of Diels-Alder reactions to many synthetic targets.

Introduction

Powerful as the Diels-Alder (DA) reaction is as a resource in chemical synthesis,1-4 it is certainly not without its limitations. Our laboratory, at various levels over the years, has been involved in addressing some of these limitations in an attempt to raise the overall applicability of DA logic. Our earliest works focused on the synthesis of, then-novel, dienes which would impart to their cycloaddition products, easily exploitable, complexity-enhancing access points.5 More recently, through the use of appropriate dienophiles, we have been able to encompass trans junctions within the scope of DA logic.6,7 We have also shown how to use Diels-Alder-initiated schemes to gain entry to double bond patterns, isomeric with those available from the DA reaction, itself.

The limitation that we address in this paper, has to do with well-established (though not fully appreciated) erosion of dienophilic activity with even, seemingly, modest levels of steric hindrance, particularly at the β-carbon of the dienophile (eq. 1). For instance, α,β-unsaturated acyl activated dienophiles (1, A = acid, ester, or amide) are relatively weakly reactive to thermally induced cycloaddition. When the acyl group is bound to a trisubstituted double bond, contained in a cyclene motif, DA reactivity can be quite sluggish (cf. 2→3).8-10 This is a troublesome limitation because it complicates the use of DA logic to synthesize angularly substituted cis-fused bicyclic motifs (cf. 3) in a facile way.

|

(1) |

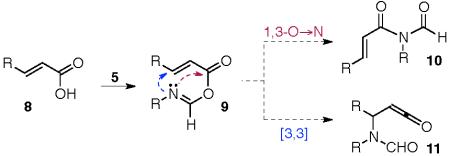

In a totally unrelated vein, we had been investigating some important, but hitherto overlooked, chemistry of isonitriles.11-13 During the course of those explorations, we discovered a rather general process, which we have termed two-component coupling (2CC), wherein carboxylic acids 4 react with isonitriles 5, generally under microwave activation, to afford N-formyl amides corresponding to 7, presumably via 1,3-O→N acyl shift of the intermediate formimi-date-carboxylate mixed anhydride (FCMA, eq. 2). In this connection, we wondered whether an α,β-unsaturated acid 8, upon reaction with an isonitrile (5), would give rise to 10 via the corresponding α,β-unsaturated FCMA, 9. Not unnoticed was the possibility that 9 would not advance to 10, but might instead undergo a formal [3,3] sigmatropic shift, leading to a ketene-bearing structure (eq. 3).

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

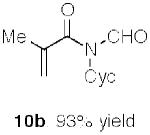

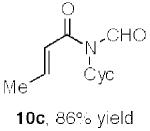

The results of early probing of this question are shown in Table 1, wherein a range of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid substrates readily suffered conversion to the corresponding acrylic N-formyl amides in high yield.14 At least at present, we have not seen any positive evidence of products arising from [3,3] sigmatropic shift, although the mode of progression of the hypothetical ketene, were it formed, is unclear.

Table 1.

Synthesis of acrylic N-formyl amides.a

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key: Cyc = cyclohexyl.

We were now in a position to evaluate whether α,β-unsaturated N-formylamides, of the type 10, might serve as useful new versions of α,β-acyl activated dienophiles. In this discussion we distinguish between acyl (A, in structures 1 and 2) and aldehydo-activated dienophiles (i.e. A = formyl). The unique opportunities in aldehyde activation, pioneered by the MacMillan school,15-17 will be discussed below. In particular, we were hoping that the N-formylamide motif might enhance dienophilicity, thereby overcoming the type of steric hindrance problems described above. It was hoped that the electron withdrawing effect of the formyl group would enhance the dienophilicity of 10 relative to that of a simple amide. Moreover, obvious possibilities for chelation–based Lewis acid promotion presented themselves.

We began by exploring strictly thermal conditions to implement cycloaddition of 10a with 1,3-cyclohexadiene (Table 2).18 For these thermal runs, we used trifluoroethanol as the solvent. In recent work in our laboratory, use of this solvent served to lower the temperature requirement for uncatalyzed cycloaddition, possibly due to reactivity enhancing interactions with the dienophile activators. 6 After 12h at reflux, ca 30% of 10a had undergone cycloaddition.19 While this is far from impressive, we noted that the corresponding N-deformylated compound, 11, upon attempted cycloaddition with the same diene, gave no observable Diels-Alder product (entry 2).

Table 2.

Diels-Alder Reactions.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| entry | dienophile | catalyst | temp. | time | yield |

| 1 | 10a, R = CHO | none | refluxa | 12h | 30% |

| 2 | 11, R = H | none | 120 °Cb | 24h | 0% |

| 3 | 10a, R = CHO | Et2AICI (2.5 eq) | 23 °Cc | 4h | 70% |

| 4 | 11, R = H | Et2AICI (2.5 eq) | 23 °Cc | 24h | 0% |

Key: (a) CF3CH2OH, rt→reflux. (b) toluene, 120 °C. (c) CH2Cl2, 0→23 °C. 3 eq. of cyclohexadiene were used in these studies.

Happily, cycloaddition was nicely promoted by Et2AlCl.20 Thus, treatment of 1,3-cyclohexadiene and dienophile 10a with 2.5 equiv. Et2AlCl at room temperature afforded the DA adduct, 12a in 70% yield and greater than 30:1 endo selectivity (entry 3).21 An excess of Lewis acid was used in these reactions in order to ensure bidentate coordination of the imide. As found by the Evans laboratory in their investigations of the oxazolidinones,22 we observed prohibitively slow reaction when sub-stoichiometric amounts of Lewis acid were used. The efficiency of this transformation is of particular note, as both cinnamates and 1,3-cyclohexadiene are generally relatively unreactive partners in DA reactions.23 In order to confirm that the high reactivity, in this case, arose from the presence of the imide functionality, a control experiment was performed. Thus, 10a was deformylated, in the presence of ammonia, to generate amide 11. As expected,24 11 did not undergo DA cycloaddition with 1,3-cyclohexadiene under Lewis acid conditions (entry 2).

Having defined effective conditions to achieve DA reaction in the cinnamate case, we next examined their applicability to other cases. As outlined in Table 3, dienophile 10a undergoes cycloaddition with a range of diene coupling partners to produce adducts 12b-12d in high yield. Notably, the α-substituted methacryl N-formyl amide, 10b, also served as a productive coupling partner, providing cycloadducts 12e and 12f in high yield and generally high stereoselectivity. The relatively modest endo selectivity (4:1) observed in the particular case of the formation of 12e is not surprising, given the known propensity of methacryl dienophiles to undergo competitive exo cycloaddition.25 Happily, a β-substituent is nicely tolerated (see formation of 12g). Not surprisingly, the challenging β,β-disubstituted dienophile, 10d, failed to provide DA adduct after 12 h at room temperature.26 Upon warming to 40 °C and stirring for an additional 6 h, ca 10% of product 12h was detected. Finally, we examined the reactivity of 1-cyclohexene-1-N-formyl amide 10e. In the context of DA chemistry, the analogous 1-cyclohexenecarboxylate is a highly sluggish dienophile.27 In contrast, the N-formyl amide– activated dienophile, 10e, smoothly undergoes Et2AlCl-mediated cycloaddition with both cyclohexadiene and 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene to generate adducts 12i and 12j, respectively.28

Table 3.

Scope studies.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key: 3 equiv. of diene were used in these reactions. endo:exo. 12e = 4:1; 12d = 25:1, 12g = 20:1, 12i = 20:1.

Having demonstrated that α,β-unsaturated N-formyl amides, under Lewis acid promotion, provide exploitable reactivity in DA chemistry, we thought it of interest to compare the dienophilicity of systems such as 10 with conventional dienophilic activators that have enjoyed long term usage. For this purpose, we conducted a series of experiments, wherein an N-formyl amide–activated dienophile competes with conventional acyl activators in the same reaction flask. We also compared the N-formyl amide with its corresponding aldehyde.

As seen in Table 4, the dienophilicity of the N-formyl amide 10 totally dominated the course of the cycloaddition relative to potential competition from ester–, acid–, and amide– activated cinnamates (entries 1–3). In the mono-carbonyl series, the only discernable competition (ca. 1:13) arose from trans-cinnamaldehyde (entry 4). We also note that, in contrast to the aldehyde, which provides an endo:exo mixture, the corresponding reaction with 10a appears to afford only the endo diastereomer. In a direct competition experiment, the N-formyl amide 10a was found to possess levels of reactivity equivalent to the well-established oxazolidinone activated dienophile (entry 5).29

Table 4.

Diels-Alder Competition Studies.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| entry | −EWG | yield (12a) | yield (13) |

| 1 | −CO2Me | 68% | 0% |

| 2 | −CO2H | 63% | 0% |

| 3 | −CONHCyc | 68% | 0% |

| 4 | −CHO | 65% | 5% |

| 5 |

|

40% | 40% |

Key: (a) 2.5 eq. Et2AlCl, 1 eq. cyclohexadiene, CH2Cl2, 3h, 0 °C→rt.

It was important to address questions as to the manipulability of the N-formyl amide in the DA product. The N-formyl amide motif may be readily converted to a range of traditional functional groups. For example, the facile three-step conversion of cycload-duct 12a to alcohol 14 and amide 15 is shown in Scheme 1.30 The amide can be further reduced to amine 16.

Scheme 1.

Functionalization of N-formyl amides adducts.

aKey: (a) (i) NaBH4, MeOH (ii) Et3SiH, TFA, CH2Cl2 (iii) LDA, BH3NH3, THF. 74% over three steps (b) NH3, MeOH, >95%. (c) LAH, Et2O, 90%.

We next envisioned expanding this technology to enable the rapid synthesis of complex polycyclic systems (cf. 20 and 24, Figure 1). This would be accomplished by coupling of “value added” isonitrile and carboxylic acid substrates, followed by intramolecular Diels-Alder (IMDA) cycloaddition. In one potential application, installation of the diene coupling partner on the isonitrile functionality (17) would serve to generate, following 2CC with an α,β-unsaturated acid, a potential IMDA substrate, 19. Subsequent Lewis acid-mediated cyclization would provide access to bicyclic systems of the type 20. Alternatively, we field tested the possibility that the acyl group could be attached to the diene (cf. 21), while the isonitrile moiety might bear the dienophilic element (22). In this setting, the N-formyl amide would serve to activate the diene of 23, thereby promoting an inverse-demand type IMDA cycloaddition to yield a complementary set of cycloadducts (cf. 24).31-33

Figure 1.

IMDA.

We first examined the feasibility of the normal demand IMDA. Thus, compound 25 was prepared from the commercially available primary amine.34 Subsequent 2CC with 26 provided IMDA substrate, 27 (Scheme 2). Notably, formation of small amounts of IMDA cyclization adduct were already observed following the microwave irradiation of the 2CC reaction. Upon treatment with Et2AlCl, the substrate readily underwent cyclization to furnish tri-cyclic adduct 28 as a single diastereomer. We next investigated the feasibility of the proposed inverse demand IMDA sequence. Intermediate 31 was thus readily prepared through 2CC of acid 29 and isonitrile 30.35 Subsequent Et2AlCl–mediated cyclization delivered 32 as the main product in good yield as a single observable diastereomer.

Scheme 2.

IMDA with acrylic N-formyl amides.

During the course of these studies we were certainly sensitive to the opportunities offered by the oxazolidinone type of dienophilic activation pioneered by Evans and associates.22 Inherent in Evans’ results was the recognition that activation by imide-based dienophiles surpasses that of the usual acyl type activators. Moreover, the very elegant adaption of such auxiliaries to the attainment of high levels of diastereo– and enantioselection has been of great utility. Also compelling has been the application of organocatalysis, resulting in major enhancement of the dienophilic propensities of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones, described by MacMillan.15-17 Here also, high levels of enantioselection, arising via diastereo-differentiated transition states, magnified the power of the catalysis. While one can imagine corresponding opportunities for high enantioselection with type 10 dienophiles, we have, presently, not achieved acceptable levels of induction. Rather, the value of the chemistry described above lies in its ability to merge complex functionalities in putative diene and dienophile sectors, by the 2CC reaction, thereby enhancing the level of molecular complexity available by this logic, while providing ample “machinery” for conducting the projected DA cycloaddition. Neither of the methods described above carry with them this level of diversity in the DA product. The critical part of the DA-enabling machinery is the N-formyl group. Following DA cycloaddition (either inter- or intra-molecular see Table 3 and Scheme 2, respectively), the N-formyl group, if extraneous to the target, is quickly discharged, leaving the rest of the complexity–enhancing functionality in place. Ongoing research is directed to building upon the paradigm, captured in Figure 2, while also seeking to gain high enantiocontrol through appropriate catalytic guidance via diastereodifferentiating transition states. Results will be reported in due course.

Figure 2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH Grant HL25848 (S.J.D.). S.D.T. is grateful to Weill Cornell for an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (CA062948). Special thanks to Dr. George Sukenick, Hui Fang, and Sylvi Rusli of SKI’s NMR core facility for spectroscopic assistance, to Rebecca Wilson for preparation of the manuscript, and to Dr. Suwei Dong for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

General experimental procedures, including spectroscopic and analytical data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kagan HB, Riant O. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:1007. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Winkler JD. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:167. doi: 10.1021/cr950029z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Corey EJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2002;41:1650. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1650::aid-anie1650>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2002;41:1668. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::aid-anie1668>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Danishefsky S, Kitahara T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;25:7807. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kim WH, Lee JH, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12576. doi: 10.1021/ja9058926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lee JH, Zhang Y, Danishefsky S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14330. doi: 10.1021/ja1073855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).a) Kloetzel M. Organic Reactions: The Diels-Alder Reaction with Maleic Anhydride. Wiley; New York: 1948. [Google Scholar]; b) Holmes H. Organic Reactions: The Diels-Alder Reaction Ethylenic and Acetylenic Dienophiles. Wiley; New York: 1948. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Oppolzer W. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Paquette LA, editors. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford, U.K.: 1991. p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Carruthers W. Cycloaddition Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li XC, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5446. doi: 10.1021/ja800612r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Li XC, Yuan Y, Berkowitz WF, Todaro LJ, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13222. doi: 10.1021/ja8047078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Li XC, Yuan Y, Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13225. doi: 10.1021/ja804709s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).The results in Table 1 describe a survey of reactions and do not reflect optimization. The selection of cyclohexyl as the substituent for nitrogen for this study was made on the basis of its robustness and commercial availability.

- (15).Ahrendt K, Borths C, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4243. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Northrup A, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2458. doi: 10.1021/ja017641u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wilson RM, Jen WS, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11616. doi: 10.1021/ja054008q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).In this opening study, we focused on diene types that are not overwhelmingly reactive. In this way, we could more readily identify unusual reactivity of the dienophile component.

- (19).The bulk of the recovered dienophile had not reacted.

- (20).The reaction was quenched before complete consumption of the starting materials to avoid formation of other products.

- (21).Miyajima S, Inukai T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1972;45:1553. [Google Scholar]

- (22).a) Evans DA, Chapman KT, Bisaha J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4261. [Google Scholar]; b) Evans DA, Chapman KT, Bisaha J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4071. [Google Scholar]; c) Evans DA, Chapman KT, Bisaha J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1238. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Fringuelli F, Taticchi A. Dienes in the Diels-Alder Reaction. John Wiley; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- (24).For examples of harsh DA reactions where the dienophile is activated by an amide see: Mukaiyama T, Iwasawa N. Chem. Lett. 1981;29 Stork G, Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:5510. Iwasawa N, Sugimori J, Kawase Y, Narasaka K. Chem. Lett. 1989;1947 Martin SF, Li W. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:642.

- (25).Corey EJ, Shibata T, Lee TW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3808. doi: 10.1021/ja025848x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Liu WJ, You F, Mocella CJ, Harman WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1426. doi: 10.1021/ja0553654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Danishefsky S, Kitahara T. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:538. doi: 10.1021/jo00901a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).The reactions described in Tables 2 and 3 were performed on 0.1 mmol scale. We have demonstrated the preparative value of this chemistry in the context of the cycloaddition of 650 mg (2.5 mmol) of 10a with cyclohexadiene to afford a 72% yield of 12a. The isolated yield of this large-scale reaction is similar to that obtained on 0.1 mmol scale (see Table 2). See Supporting Information for details.

- (29).On the advice of one reviewer, we also performed the competition experiments in Table 4 with 5 equivalents of Et2AlCl and observed no change in product distribution.

- (30).We note that to accomplish the transformation to 14, it was necessary to convert N-formyl to N-methyl.

- (31).Sauer J, Sustmann R. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1980;19:779. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Boger DL, Mullican MD. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:4033. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ireland RE, Anderson RC, Badoud R, Fitzsimmons BJ, Mcgarvey GJ, Thaisrivongs S, Wilcox CS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:1988. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Porcheddu A, Giacomelli G, Salaris M. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:2361. doi: 10.1021/jo047924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kappe CO, Murphree SS, Padwa A. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:14179. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.