Abstract

Cervical cancer is one of the most common gynecologic malignancies and poses a serious health problem worldwide. Identification and characterization of cervical cancer stem cells may facilitate the development of novel strategies for the treatment of advanced and metastatic cervical cancer. Breast cancer-resistance protein (Bcrp1)-positive cells were selected from a population of parent HeLa cells using flow cytometry. The invasion capacity of Bcrp1-positive and -negative cells was analyzed with a Boyden chamber invasion test. The tumorigenicity of these cells was determined by in vivo transplantation in non-obesity diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice. The Bcrp1-positive subpopulation accounted for about 7% of the parent HeLa cell population. The proliferative capacity of the Bcrp1-positive cells was greater than that of the Bcrp1-negative cells (P < 0.05). In the invasion assay, the Bcrp1-positive cells demonstrated a greater invasive capacity through the artificial basement membrane than their Bcrp1-negative counterparts. Following transplantation of 104 cells, only the Bcrp1-positive cells formed tumors in NOD/SCID mice. When 105 or 106 cells were transplanted, the tumor incidence and the tumor mass were greater in the Bcrp1-positive groups than those in the Bcrp1-negative groups (P < 0.05). The Bcrp1-positive subpopulation cervical cancer stem cells.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Cancer stem cells, Bcrp1

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common gynecological malignancies. With the introduction of cervical cytological scanning and improved early diagnosis, its morbidity and mortality have significantly decreased in the past four decades (Bansal et al. 2009; Kosmas et al. 2009). Most cases of clinical early-stage disease (stages IA1-IIA, according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) are treated and cured with either hysterectomy or primary radiotherapy. However, many cases are not diagnosed until later stages: approximately 35% at the time of regional metastases, and 10% have distant metastases. In spite of therapeutic measures such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the overall recurrence rate within 1 year upon the completion of therapy is 50%, and 75–80% within 2 years in these patients. Local recurrence in the pelvic cavity accounts for 70%, and distant metastasis for the remaining 30%.

According to the cancer stem cell theory (Tu et al. 2002; Szotek et al. 2006; Al-Hajj et al. 2003), cancer is a stem cell disease. Cancer stem cells have the potential for infinite proliferation, and play a crucial role in the initiation and progress of tumorigenesis. The remaining subpopulation in the tumor is fated for death through transient differentiation. In addition, some authors suggest that tumor stem cells are responsible for the recurrence and metastasis of tumors (Tu et al. 2002). Identification and characterization of tumor stem cells would therefore provide a basis for the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The isolation of cancer stem cells, also known as side population (SP) selection, is based on the recognition of their biological features (Szotek et al. 2006). SP cells exhibit the capacity for almost unlimited self-renewal and proliferation in vitro and form tumors in vivo with an inoculation of very low cell numbers in mice. Thus the SP cell is regarded as a tumor stem cell (Tu et al. 2002). In the absence of a specific surface marker for the related tumor stem cell, isolation using the DNA staining dye Hoechst 33342 is an important method of identification. However, Hoechst 33342 is not completely non-toxic. In cells which undergo the SP selection, particularly those of the non-SP phenotype, chronic accumulation of the staining dye results in an unpredictable influence on biological features and functions of the cells. Recently the expression of breast cancer-resistance protein (Bcrp1) has become a biological basis of isolation. It is independent of the use of Hoechst 33342, and therefore is an important method for the isolation of cancer stem cells.

Despite the isolation and characterization of cancer stem cells from a wide variety of other malignancies, there has been no report on cervical cancers or cell lines of cervical cancer. Such identification could lead to the improvement of our ability to develop novel preventive and therapeutic modalities for this disease. With an improved methodology, we attempted to isolate and characterize SP cells from HeLa, a cell line derived from a patient with cervical cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials

The parent HeLa cell line was purchased from the Shanghai Cell Institute at the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Bcrp1 and the directly-labeled human BCRP1 antibody, Matrigel, and Transwells were bought from the BD Corporation (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The fluorescent labeling reagents fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and Cy3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The staining kit for immunohistology was obtained from Maixin Biotechnology (Fuzhou, China). The proliferation determination kit for propidium iodide (PI) labeling was purchased from Dingguo (Beijing, China). The standardized fetal bovine sera were obtained from Haoyang Biotechnology (Tianjin, China). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose and trypsin was purchased from GIBCO (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The 6–8 week-old non-obesity diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) female mice were obtained from Fuzhong Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

HeLa cell line culture

HeLa cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The doubling time was about 72 h and the nearly confluent cells (about 80%) were passaged at a ratio of 1:3.

Cell sorting with flow cytometry (FCM)

The nearly confluent cells were detached with 0.25% trypsin/0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 106 cells in 20 μL of PBS were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled mouse anti-human BCRP1 monoclonal antibody for about 30 min in the dark. Then the Bcrp1-positive (Bcrp1+) cells were collected and sorted by FCM (BD FACS Calibur, Franklin Lakes/NJ, USA).

Evaluation of cell proliferation

After FCM sorting, Bcrp1+ or Bcrp1− cells were seeded onto 24 well plate at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for indicated time period. For determination of cell growth ability, cells were digested by trypsin and subsequently stained with trypan blue, a living-cell exclusion dye. Each treatment was performed in triplicate. The average number of live cells was calculated and growth curve was drawn.

In vivo tumorigenesis in NOD/SCID mice

Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− HeLa cells (103, 104, 105, or 106 cells), in 200 μL DMEM/F12 were inoculated subcutaneously into 6–8 week old female NOD/SCID mice (5 mice/group). Close observation was carried out for tumor formation and the tumor size. After 8–12 weeks, the mice were sacrificed and the tumor tissues were removed and weighed. The protocol regarding animal welfare assurance had been reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Jiling University.

Boyden chamber invasion assay

According to the method described by Albini et al. (1987), HeLa cell invasion into restructured basement membrane was examined with a Boyden chamber. The cell insert was placed in a 24-well plate. Matrigel was diluted with DMEM at a ratio of 1:3. The amount of 20 μL of diluted Matrigel was added to the insert every 10 min, and the total amount of Matrigel was 60 μL. The plate was incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min. Then the Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− cells were added to the upper compartment separately and 200 μL of NIH-3T3 conditioned medium was added to the lower compartment. The plate was incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 5 h (h). The amount of invasive cells and the depth of invasion were observed with a confocal scanning microscope (Olympus).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Student’s t test and the χ2 test were used where appropriate. The statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 13.0 software.

Results

Morphology and proliferative characteristics of the cancer stem cell

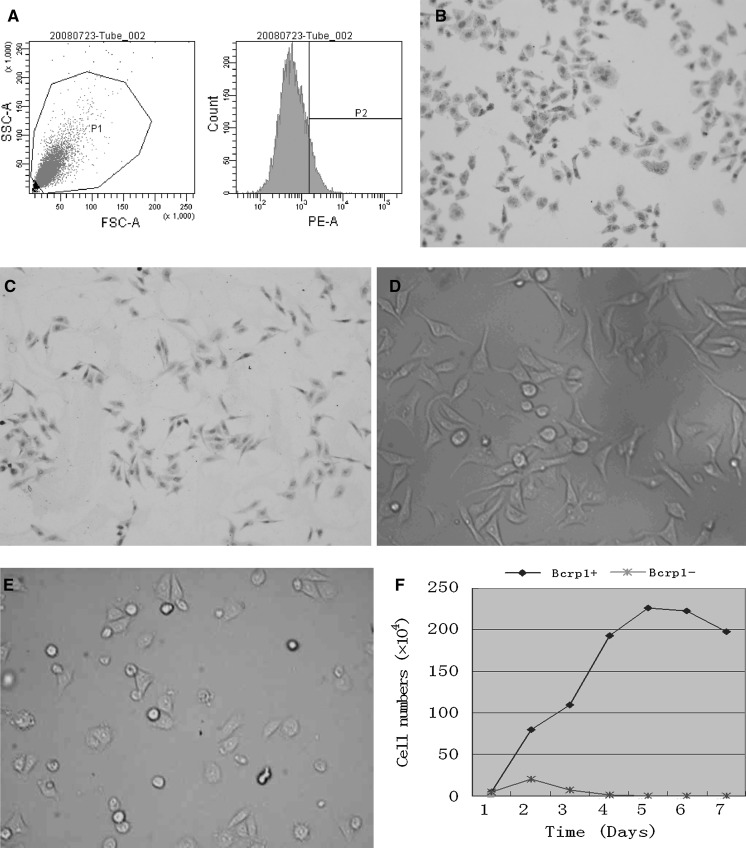

The HeLa cell culture contained a small fraction of Bcrp1+ subpopulation. Upon repeated sorting with FCM, it was confirmed that the Bcrp1+ subpopulation accounted for about 7% of HeLa cells (Fig. 1a, b and c). Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− cells were inoculated in DMEM with 10% FBS and incubated for 4 days. The majority (nearly 72.8%) of the Bcrp1+ cells anchored to the bottom of the flask 24 h after incubation. Vigorous proliferative capability correlated with culture duration (Fig. 1d). Meanwhile, the attachment of Bcrp1− cells required at least 48 h. The proportion that attached was about 18.7% and the death rate was about 87.4%, 72 h after inoculation (Fig. 1e). We next investigated the growth ability of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− cells after sorting. As shown by Fig. 1f, the number of Bcrp1+ cells was gradually increased with time. However, the number of Bcrp1− cells was slightly elevated on the second day after seeding, but decreased thereafter. Barely any live Bcrp1− cells were detected on Day 4 after seeding (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

a Upon repeated sorting with FCM, the HeLa cell culture contained a 7% Bcrp1+ subpopulation. During FCM sorting, gate P1 in SSC-A/FSC-A dot plots was created to exclude cell debris and cell clumps (left panel), and gate P2 was created to exclude cells with positive staining (right panel). Hence, cell plots on the right side of the vertical line were defined as Bcrp1+ subpopulation whereas cell plots on the left side of the vertical line were defined as Bcrp1− subpopulation. The percentage of Bcrp1+ cells was calculated. b, c Immunostaining results of HeLa cells with an anti-Bcrp1 antibody, b showed Bcrp1+ cells with Bcrp1 positive staining (dark brown staining of cytoplasm) and c showed the Bcrp1− cells without Bcrp1 positive staining. d, e The morphology of Bcrp1+ (D) and Bcrp1− (E) HeLa cells after 48 h of culture. f Growth curves of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− cells. Y-axis indicates the average number of living cells; X-axis indicates the day after seeding. (Color figure online)

In vivo tumorigenicity in SCID mice

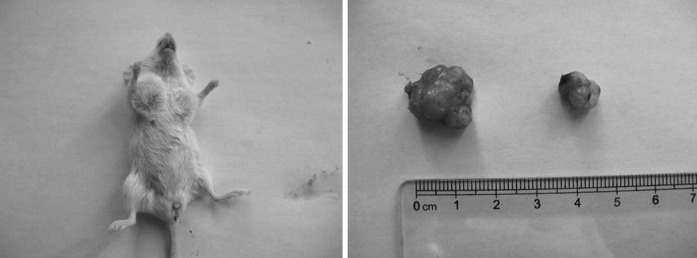

The two groups of HeLa cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the NOD/SCID mice to observe their tumorigenic capability. No tumor formed in either group when 103 cells were transplanted. When 104 Bcrp1+ cells were transplanted, tumors formed in about 60% of the NOD/SCID mice. Moreover, 12 weeks after inoculation, the tumor volume in the Bcrp1+ HeLa cell group was 1.3 × 1.3 × 1.1 cm3. However, at the same level of cells transplanted into the Bcrp1− group, no tumor was formed even at 12 weeks after inoculation (Table 1). When 105 or 106 cells were transplanted, the incidence was significantly higher and the size of tumors was much bigger in the Bcrp1+ group than in the Bcrp1− group (P < 0.05 for transplantation with either 105 or 106 cells; Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Tumorigenicity of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− HeLa cells in NOD/SCID mice

| Injected cell number | Incidence (number of mice, n) | Average volume of tumors (cm3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcrp1+ | 103 | 0/5 | 0 |

| 104 | 3/5 | 0.822 | |

| 105 | 5/5 | 1.157 | |

| 106 | 5/5 | 1.317 | |

| Bcrp1− | 103 | 0/5 | 0 |

| 104 | 0/5 | 0 | |

| 105 | 3/5 | 0.764 | |

| 106 | 4/5 | 1.108 |

Fig. 2.

Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− HeLa cells (1 × 105 each) were injected subcutaneously into the ventral side of the right and left front limbs, respectively, in NOD/SCID mice. After 5 weeks, visible tumor nodules are present at the right side. At 10 weeks, there was no tumor formation that could be observed macroscopically at the left side. At 12 weeks, the tumor volume in the Bcrp1+ HeLa cell group was 1.4 × 1.4 × 1.3 cm3; in the Bcrp1− group, it was 0.7 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm3

Invasive capability

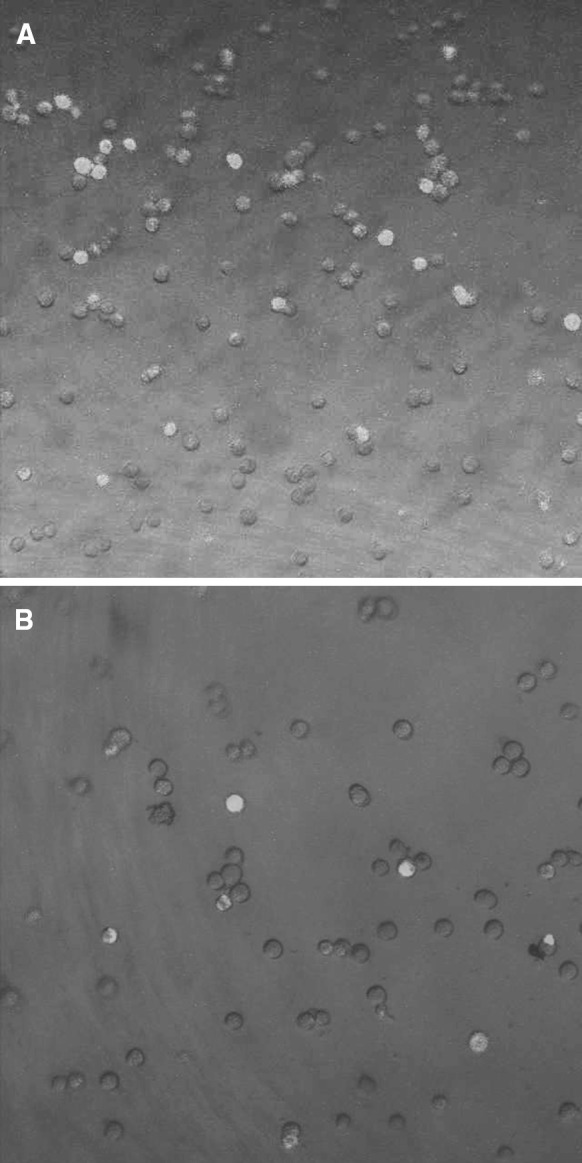

To explore the invasive capability of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− HeLa cells, Boyden chamber invasion assay was applied. As revealed by Fig. 3, after 5 h incubation at 37 °C, the amount of cells that invaded through the artificial basement membrane in the Bcrp1+ group was significantly greater than that in the Bcrp1− group (99 ± 11.2 per 105 cells vs. 57 ± 7.3 per 105 cells, P < 0.05). These results indicated that the invasive capability of Bcrp1+ HeLa cells was higher than that of Bcrp1− HeLa cells.

Fig. 3.

Invasive capability of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− HeLa cells. Rhodamine-stained Bcrp1+(a) and Bcrp1− HeLa cells (b) invaded through the artificial Matrigel basement membrane. Cells were visualized under confocal scanning microscope. Enhanced invasive capability was found in Bcrp1+ cells

Discussion

Neoplastic cells exhibit marked heterogeneity with respect to proliferation and differentiation (Bonnet and Dick 1997; Reya et al. 2001). For example, rare stem cells within the leukemic population have extensive proliferation and self-renewal capacities that are not found in the majority of leukemic cells. Further researches on leukemic stem cells demonstrate that they are necessary and sufficient to maintain leukemia properties (Bonnet and Dick 1997; Lapidot et al. 1994). In 2003, Al-Hajj et al. firstly reported the isolation and identification of the tumorigenic cells CD44+CD24−/low in eight of nine patients. As few as 100 cells with this phenotype were able to form tumors in mice, whereas tens of thousands of cells with alternate phenotypes failed to form tumors (Al-Hajj et al. 2003). In the same year, Singh et al. reported the successful isolation, using CD133 magnetic beads, of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors (Singh et al. 2003). Following this, in a wide array of solid malignancies such as pancreatic carcinoma, ovarian cancers, prostate cancer and cancer stem cells have been isolated successfully (Tu et al. 2002; Bapat et al. 2005; Olempska et al. 2007; Collins et al. 2005). Szotek et al. suggest that the inherent metastatic and heterogeneous nature of cancers may be due to their derivation from distinct stem cells (Szotek et al. 2006).

In normal tissues, stem cells safeguard tissue homeostasis and guarantee tissue repair throughout life. The decision between self-renewal and differentiation is influenced by a specialized microenvironment called the stem cell niche (Mitsiadis et al. 2007). Stem cells in the niche always maintain quiescent status. Although there is no report of exploring the niche of cancer stem cells, we postulate that the localization of cancer stem cells in niches and protection from the damage of cytotoxic drugs could be one of the determinants for the ability of cancer to metastasize, recur and resist chemotherapy. On the other hand, cancer stem cells express higher levels of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, including those encoded by the multidrug-resistant (MDR) gene 1, the MDR protein, and Bcrp1, which contribute to drug resistance in many cancers by pumping drugs out of the cell. Hence, cancer stem cells exhibit another distinct feature, a high drug efflux capacity (Hirschmann-Jax et al. 2004; Kondo et al. 2004).

In this study we explored, for the first time, the isolation and characterization of cancer stem cells using Bcrp1 expression. The results indicated that Bcrp1+ HeLa cells account for approximately 7% of the entire population. The two subpopulations (Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1−) presented similar epithelial malignancies, and there was no significant difference in the morphology of the two populations under the microscope.

Bcrp1+ HeLa cells attached to the culture flask more quickly than did Bcrp1− cells; 72.8% of the cells attached to the bottom within 24 h of culture. Moreover, Bcrp1+ HeLa cells presented a more vigorous growth capacity under the conditions of in vitro culture compared to Bcrp1− cells. Regarding the Bcrp1− cells, there was no obvious attachment within 24 h of culture, and at 48 h only 18.7% had attached. It is suggested that, although Bcrp1− cells account for the majority of the population of HeLa cells, their proliferative capacity is weak and their ability to self-renew is lacking. Upon the deletion of Bcrp1+ cells from the HeLa population through cell sorting with FCM, the majority of the remaining cells were committed to death. Repeating, there was a lower percentage of Bcrp1+ HeLa cells in the whole population, yet Bcrp1+ HeLa cells played the deciding role in the immortalization of the HeLa cell line. The Bcrp1+ subpopulation should be regarded as cervical cancer stem cells or the major component of cervical cancer stem cells (Fig. 1). A previous study revealed that the human monoblastoid U937 tumor cells have differentiation and retrodifferentiation characteristics (Hass et al. 1990). However, in this study, we found that Bcrp1+ cells could be differentiated into Bcrp1− cells. After repeated passage, the ratio of Bcrp1+ and Bcrp1− cells was similar as HeLa cells before sorting. However, Bcrp1-negative cells could not be re-differentiated into Bcrp1+ cells, as Bcrp1− cells could not survive during long-term culture.

In addition to the in vitro functional characterization of the Bcrp1+ HeLa cell, the in vivo transplantation into NOD/SCID mice was necessary to verify its tumorigenicity. Al-Hajj et al. reported that from the phenotypically diverse populations of a single cell suspension of primary breast cancer, CD44+CD24−/lowlineage− cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice with very few cells. The CD44+CD24−/lowlineage− cells were able to form tumors in mice, whereas tens of thousands of the remaining cells (negative selection cells) failed to form tumors. Due to the features of extensive proliferation, self-renewal, and tumorigenesis in mice, the CD44+CD24−/lowlineage− cell population could be regarded as the breast cancer stem cell observed by Al-Hajj et al (2003). Our results reported here indicate that compared to the Bcrp1− HeLa cell, the Bcrp1+ HeLa cell exhibited enhanced tumorigenic capacity; with the inoculation of fewer cells, a tumor could be formed. With an equal number of cells inoculated, the volume of the tumor caused by Bcrp1+ cells was much larger than that of the Bcrp1− cells. This suggests that cervical cancer stem cells exist in Bcrp1+ HeLa cells (Fig. 2, Table 1). Moreover, Lewis et al. indicated that the TPD50 (log10) (tumor producing dose in 50% of the animals) for HeLa cells was 4.9, which means that when injecting 104.9 cells into nude mice, 50% of them come down with tumor growth (Lewis et al. 2001). Similar results were obtained in the present study. When 104 Bcrp1+ cells were transplanted, tumors formed in about 60% of the NOD/SCID mice, and inoculation of 105 Bcrp1+ cells led to 100% of the tumor generation in nude mice (Table 1).

The in vitro Boyden assembled basement membrane invasion assay is widely used to investigate the ability of tumor cells to invade and metastasize. Using this assay, we observed that, compared to Bcrp1− HeLa cells, more cells in the Bcrp1+ HeLa cell group migrated through the basement membrane and presented with an enhanced invasion capacity. Invasion capacity is one of the important determinants for metastasis and prognosis, and one of the main features of tumor stem cells. The theory on tumor stem cells suggests that tumor stem cells could migrate to specific organs and lead to tumor metastasis. It is possible that the organ or tissue specificity of tumor metastasis is due to the relatively small number of tumor stem cells that contribute to the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion of the tumor, while the remaining majority of tumor cells lack the capacity for metastasis. In this study we observed an increased invasive capacity of Bcrp1+ cells. It can therefore be postulated that cervical cancer stem cells are contained in a subpopulation of cells. We speculate that within a population of Bcrp1+ HeLa cells there is a certain number of cervical cancer stem cells (Fig. 3).

In the study reported here, we isolated the Bcrp1+ cell from the HeLa cell line, a cell line which is used universally as an in vitro cervical cancer model. We identified the subpopulation of cells that had a more vigorous proliferative capacity and greater invasion ability in vitro, and increased tumorigenesis in NOD/SCID mice. Collectively, our results indicate that the Bcrp1+ subpopulation of HeLa putatively consists of cervical cancer stem cell. Targeting this cell subpopulation may contribute to a favorable prognosis in patients with relapsed and/or metastatic cervical cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30901589).

Contributor Information

Song-Ling Zhang, Phone: +86-431-88782182, FAX: +86-431-85166199, Email: slzhangsl@yahoo.com.cn.

Yu-Lin Li, Phone: +86-13904312889, Email: ylli@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- Albini A, Iwamoto Y, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, Aaronson SA, Kozlowski JM, McEwan RN. A rapid in vitro assay for quantitating the invasive potential of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3239–3245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Shaw RE, Burke WM, Deutsch I, Wright JD. Primary therapy for early-stage cervical cancer: radical hysterectomy vs radiation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:e481–e489. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapat SA, Mali AM, Koppikar CB, Kurrey NK. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3025–3029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass R, Giese G, Meyer G, Hartmann A, Dork T, Kohler L, Resch K, Traub P, Goppelt-Strube M. Differentiation and retrodifferentiation of U937 cells: reversible induction and suppression of intermediate filament protein synthesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 1990;51:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, Goodell MA, Brenner MK. A distinct “side population” of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14228–14233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400067101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:781–786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmas C, Mylonakis N, Tsakonas G, Vorgias G, Karvounis N, Tsavaris N, Daladimos T, Kalinoglou N, Malamos N, Akrivos T, Karabelis A. Evaluation of the paclitaxel-ifosfamide-cisplatin (TIP) combination in relapsed and/or metastatic cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AM, Jr, Krause P, Peden K. A defined-risks approach to the regulatory assessment of the use of neoplastic cells as substrates for viral vaccine manufacture. Dev Biol (Basel) 2001;106:513–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsiadis TA, Barrandon O, Rochat A, Barrandon Y, Bari C. Stem cell niches in mammals. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3377–3385. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olempska M, Eisenach PA, Ammerpohl O, Ungefroren H, Fandrich F, Kalthoff H. Detection of tumor stem cell markers in pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F, Maclaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11154–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SM, Lin SH, Logothetis CJ. Stem-cell origin of metastasis and heterogeneity in solid tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:508–513. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00820-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]