Abstract

Background

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) detected by computed tomography is a non-invasive measure of coronary atherosclerosis, that underlies most cases of myocardial infarction (MI). We aimed to identify common genetic variants associated with CAC and further investigate their associations with MI.

Methods and Results

Computed tomography was used to assess quantity of CAC. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for CAC was carried out in 9,961 men and women from five independent community-based cohorts, with replication in three additional independent cohorts (n=6,032). We examined the top single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with CAC quantity for association with MI in multiple large genome-wide association studies of MI. Genome-wide significant associations with CAC for SNPs on chromosome 9p21 near CDKN2A and CDKN2B (top SNP: rs1333049, P=7.58×10−19) and 6p24 (top SNP: rs9349379, within the PHACTR1 gene, P=2.65×10−11) replicated for CAC and for MI. Additionally, there is evidence for concordance of SNP associations with both CAC and with MI at a number of other loci, including 3q22 (MRAS gene), 13q34 (COL4A1/COL4A2 genes), and 1p13 (SORT1 gene).

Conclusions

SNPs in the 9p21 and PHACTR1 gene loci were strongly associated with CAC and MI, and there are suggestive associations with both CAC and MI of SNPs in additional loci. Multiple genetic loci are associated with development of both underlying coronary atherosclerosis and clinical events.

Keywords: cardiac computed tomography, coronary artery calcification, coronary atherosclerosis, genome-wide association studies, myocardial infarction

Introduction

Atherosclerosis in coronary arteries underlies most cases of myocardial infarction (MI) and other clinical coronary heart diseases (CHD). CHD comprises the leading cause of death in Western countries.1 Extent of coronary atherosclerosis may be determined with non-invasive, high resolution computed tomography (CT) to measure coronary artery calcification (CAC).2 CAC quantity is heritable3, significantly higher in persons with a parental history of CHD4, correlates with increased burden of subclinical coronary plaque 5, and predicts incident CHD in multiple ethnic populations after adjustment for other traditional CHD risk factors.2;6;7

Genome-wide association (GWA) studies identified common genetic variation influencing risk of MI, including a strongly replicated association on chromosome 9p21,8–13 as well as strong associations with PHACTR111 and over nine other loci.8;11 Recently, a large meta-analysis of 14 GWAS for coronary disease phenotypes in the Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome wide Replication and Meta-analysis (CARDIoGRAM) Consortium, reported a total of 24 loci including the previously known loci for MI.14 Neither chromosome 9p21, nor any other locus associated with CHD, has been shown to be associated with the CAC quantity at a genome-wide significance level. We conducted a meta-analysis to identify loci underlying variation in extent of CAC. We further assessed whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with CAC quantity were also associated with MI, and whether SNPs previously shown to be associated with MI are associated with CAC quantity.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a meta-analysis of GWA data in 9,961 participants of European ancestry from five large cohorts. The study was performed in the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium15 including data from the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik),16;17 the Framingham Heart Study (FHS),18–20 the Rotterdam Study I (RS I), and Rotterdam Study II (RS II).15;21 In addition, participants from the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy Study (GENOA) were included.22 Each study received institutional review board approval and all participants gave written informed consent. These cohorts are described in the online-only Supplemental Materials.

Measures

CAC Measurement

Different cohorts used different CT scanners to assess CAC as described in the online-only Supplemental Materials. Total calcium score, based on the sum of the individual coronary arteries (left main, left anterior descending, circumflex, and right coronary arteries), was quantified using the Agatston method23 and used as CAC quantity in analyses. Prior studies by others confirm the highly significant association between CAC scores obtained by the different scanners used in the present study.24;25 Because the two scanning techniques yield similar results and the available evidence for prediction of CVD risk is similar regardless of use of electron beam CT or multi-detector CT, consensus clinical guidelines recommending clinical use of CT allows for the use of either electron beam CT or multi-detector CT.26

Genotyping and Imputation

Different discovery cohorts used different genotyping platforms: Illumina 370CNV for AGES-Reykjavik, AffymetrixHuman 500K and gene-centric 50K for FHS, Illumina 550K version 3 for RS I and II, and Affymetrix 6.0 for GENOA. Each study imputed genotype data to 2.5 million non-monomorphic, autosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using HapMap haplotypes (CEU population, release 22, build 36) with the imputation software MACH (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/MACH/) and SNPs that passed quality-control criteria (described in the online-only Supplemental Materials). All studies imputed genotype dosage, from 0 to 2, which is the expected number of alleles. Extensive quality control analyses were performed as described in the online-only Supplemental Materials.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted a GWA analyses in each discovery cohort independently. Each study evaluated population substructure in their cohort, primarily using principal components from EIGENSTRAT.(http://genepath.med.harvard.edu/~reich/EIGENSTRAT.htm). To reduce non-normality, total CAC score was natural log transformed after adding one and adjusted for age and sex variation. Data were analyzed using linear regression in AGES-Reykjavik, RS I and RS II and linear mixed effects models to account for family covariance structure in FHS and GENOA with an additive genetic model. Fixed effects meta-analysis was conducted using the inverse variance weighted approach in METAL (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/metal). Genomic control was applied to each cohort prior to meta-analysis. The inflation of the association test statistic, λgc, was: 1.10 for AGES-Reykjavik, 1.00 for FHS, 1.01 for GENOA, 1.04 for RS I, and 1.01 for RS II. Tests for homogeneity of observed effect sizes across cohorts were conducted using METAL. The analyses were repeated with further adjustment for total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, type II diabetes, hypertension status, current smoking and use of statins. The analyses were also repeated excluding individuals with a prior MI.

The association of each SNP with CAC score >100 versus <100, a threshold that is an independent predictor of clinical events,7 was also investigated in each discovery cohort. Details of the analyses are found in the online-only Supplemental Material.

The a priori threshold for genome-wide significance was 5×10−8, and a P-value > 5×10−8 but < 5×10−6 was considered moderate evidence for association. With a sample size of 9,961, a minor allele frequency of 0.25, an additive model with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 2 (mean and standard deviation similar to residuals from log (CAC score + 1) adjusted for age and sex), and alpha at 5×10−8, we had at least 80% power to detect a beta-coefficient of ≥0.21 or ≤ −0.21 in analysis of CAC quantity.

Replication

Replication cohorts included 6,032 participants from the Family Heart Study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Amish Family Calcification Study. Details about these cohorts, the CAC measures, the genotyping, and statistical analysis are provided in the online-only Supplemental Material. Meta-analysis was repeated for the replication cohorts alone and then for the discovery and replication cohorts combined.

Association with MI

To test for association with MI, we chose a set of 1150 SNPs associated with CAC quantity, at a P-value of less than or equal to 10−3, that were non-redundant at a linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold of r2 ≥ 0.8 among the HapMap CEU using SNAP.27 The four studies, including participants from three studies independent of the CHARGE consortium, were: Heart and Vascular Health (HVH) Study, the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (MIGen),11 the Gutenberg Heart Study/Atherogene Study (CADomics),28 and the CHARGE Consortium.15 These studies, including 34,508 participants (6,811 with MI), are described in Supplemental Tables S2a and S2b. A Bonferroni adjusted P-value of 4.3×10−5 was used as the threshold for significance.

Results

CAC Discovery

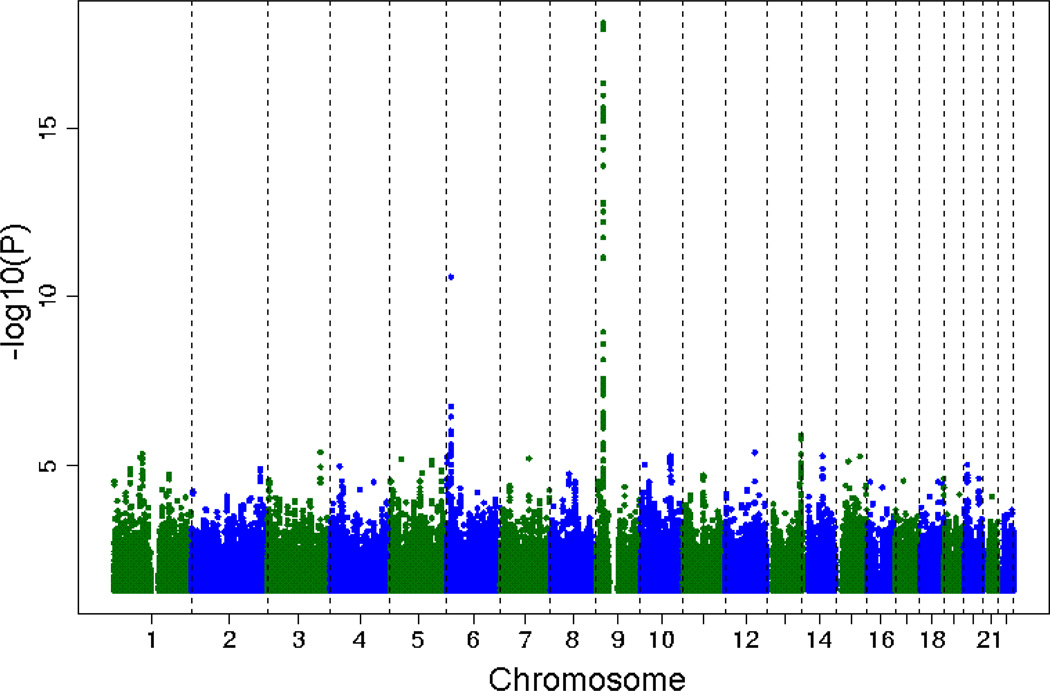

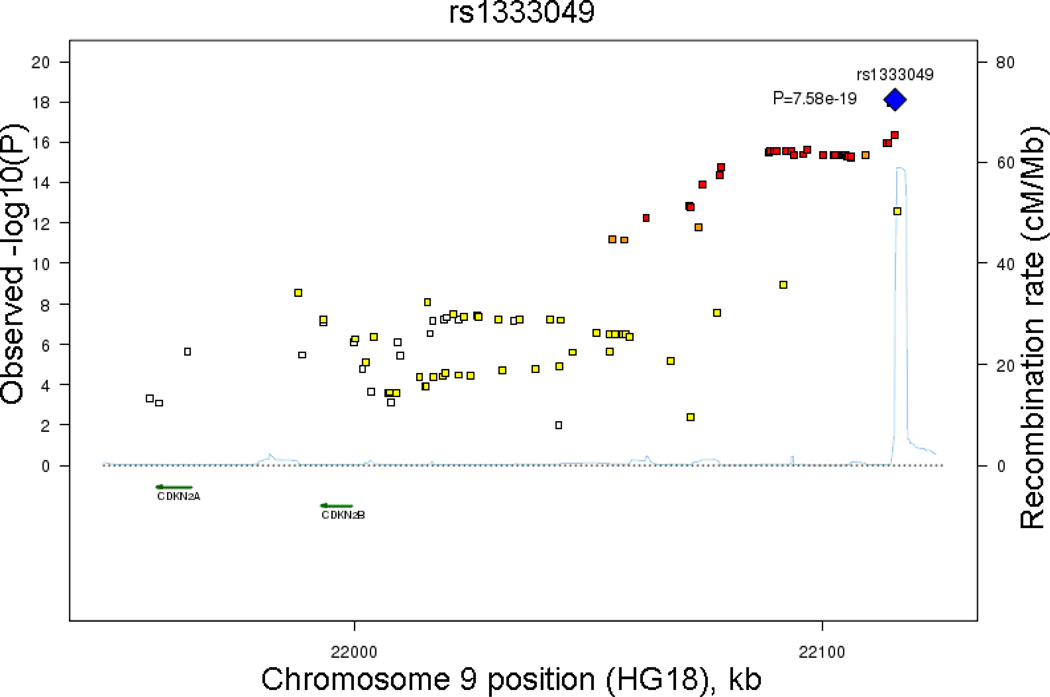

Characteristics of the five discovery cohorts are presented in Table 1. The cohort differences in the distribution of CAC reflect the cohort differences in the age and sex distributions. Figure 1 provides a plot of the meta-analysis P-values by chromosome position. Forty-eight SNPs located on chromosome 9p21 near CDKN2B and CDKN2A and one SNP on chromosome 6p24 attained genome-wide significance. Table 2 lists the genome-wide significant SNPs as well as those considered moderately associated with CAC quantity. Figure 2a provides a plot of meta-analysis P-values for SNPs near rs1333049, the variant most strongly associated with CAC quantity in our meta-analysis as well as with CHD in previously reported GWA study reports.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics of the five discovery cohorts in the meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of coronary artery calcification

| Characteristic Mean (SD) or N (Percent) |

AGES-Reykjavik N=3,177 |

FHS N=3,207 |

GENOA N=629 |

RS I N=1,720 |

RS II N=1,228 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of CAC measurements | 2002–2006 | 2002–2005 | 2000–2004 | 1997–2000 | 2003–2006 |

| Scanner Type | MDCT, 4 Detector | MDCT, 8 Detector | EBCT (C-150) | EBCT (C-150) | MDCT, 16 or 64 Detector |

| Age, years | 76.4 (5.5) | 52.2(11.6) | 58.0 (9.8) | 70.7 (5.5) | 67.2 (6.7) |

| Women, % | 58 | 49 | 58 | 54 | 53 |

| Mean CAC Score | 686 (1011) | 131 (432) | 191 (487) | 505 (969) | 312 (712) |

| Maximum CAC Score | 8,673 | 5,016 | 4,867 | 12,611 | 8,636 |

| Detectable CAC, % | 88.2 | 41.6 | 68.2 | 91.0 | 80.0 |

| CAC score >100, % | 66.7 | 19.0 | 28.3 | 54.4 | 40.5 |

| CAC score >300, % | 48.8 | 10.3 | 14.3 | 36.3 | 25.7 |

| Hypertension, % | 80.1 | 28.0 | 71.2 | 61.9% | 63.8 |

| Diabetes, % | 11.5 | 5.2 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 10.2 |

| Current cigarette smoker, % | 12.7 | 12.9 | 9.5 | 17.3 | 14.9 |

| Former cigarette smoker, % | 45.3 | 34.5 | 34.2 | 54.7 | 54.1 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.70 (1.17) | 5.08 (0.91) | 5.18 (0.88) | 5.83 (0.96) | 5.70 (0.98) |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.61 (0.47) | 1.40 (0.44) | 1.35 (0.41) | 1.40 (0.39) | 1.45 (0.38) |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.22 (0.67) | 1.44 (1.01) | 1.80 (1.19) | 1.54 (0.79) | NA |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.1 (4.4) | 27.7 (5.3) | 30.7 (6.3) | 27.0 (3.9) | 27.8 (4.9) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 101 (12) | 97 (16) | 101 (16) | 94 (11) | 94 (12) |

| Prevalent MI, % | 7.5 | 1.2 | 0 | 7.7 | 4.2 |

Abbreviations: CAC=coronary artery calcification AGES-Reykjavik=Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Study; BMI=body mass index; FHS=Framingham Heart Study; HDL=high density lipoprotein; GENOA=Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy; RS=The Rotterdam Study; MDCT=multidetector computed tomography; EBCT=electron beam computed tomography; MI=myocardial infarction; NA=not available.

Figure 1.

Plot of –log10(P) for association of SNPs and chromosomal position for all autosomal SNPs analyzed in the age and sex-adjusted model of CAC quantity in the meta-analysis of five independent discovery cohorts.

Table 2.

Top SNP association results for coronary artery calcification quantity in the meta-analysis of five discovery cohorts

| SNP | Chr | Position | Closest Reference Gene† |

Distance from Nearest Transcript†† |

Beta Coefficient |

SE | P | Coded Allele Frequency |

Coded allele |

Non- coded allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associations with P<5.0 × 10−8 | ||||||||||

| rs1333049* | 9 | 22,115,503 | (CDKN2B) | 116,191 | 0.269 | 0.030 | 7.58 × 10−19 | 0.47 | C | G |

| rs9349379** | 6 | 13,011,943 | PHACTR1 | 186,125 | −0.211 | 0.032 | 2.65 × 10−11 | 0.59 | A | G |

| Associations with 5.0 × 10−8 < P <5.0 × 10−6 | ||||||||||

| rs2026458** | 6 | 12,933,860 | PHACTR1 | 108,042 | 0.162 | 0.031 | 1.78 × 10−7 | 0.46 | T | C |

| rs3809346 | 13 | 109,758,944 | COL4A2 | 1,313 | 0.154 | 0.032 | 1.25 × 10−6 | 0.43 | A | G |

| rs6783981 | 3 | 169,010,823 | SERPINI1 | 15,225 | −0.140 | 0.030 | 3.94 × 10−6 | 0.51 | T | C |

| rs17676451 | 12 | 94,899,916 | HAL | 8,644 | −0.170 | 0.037 | 4.08 × 10−6 | 0.22 | A | G |

| rs6604023 | 1 | 91,717,485 | (CDC7) | 21,546 | 0.184 | 0.040 | 4.29 × 10−6 | 0.18 | C | G |

| rs8001186 | 13 | 109,174,856 | (IRS2) | 29,328 | −0.148 | 0.032 | 4.51 × 10−6 | 0.67 | T | G |

An additional 66 SNP’s with P<5.0E-07 were located near rs1333049 in a 128,041 bp region of chromosome 9 between position 21,987,872 and 22,115,913. See Supplemental Table S3.

SNP rs9349379 and rs2026458 reside 78,083 bp apart and are only moderately correlated (r2 0.374, D’ 0.715).

Genes for SNPs that are outside the transcript boundary of the protein-coding gene are shown in parentheses [e.g., (CDKN2B)].

Distance in base pairs from nearest start or stop site for transcription.

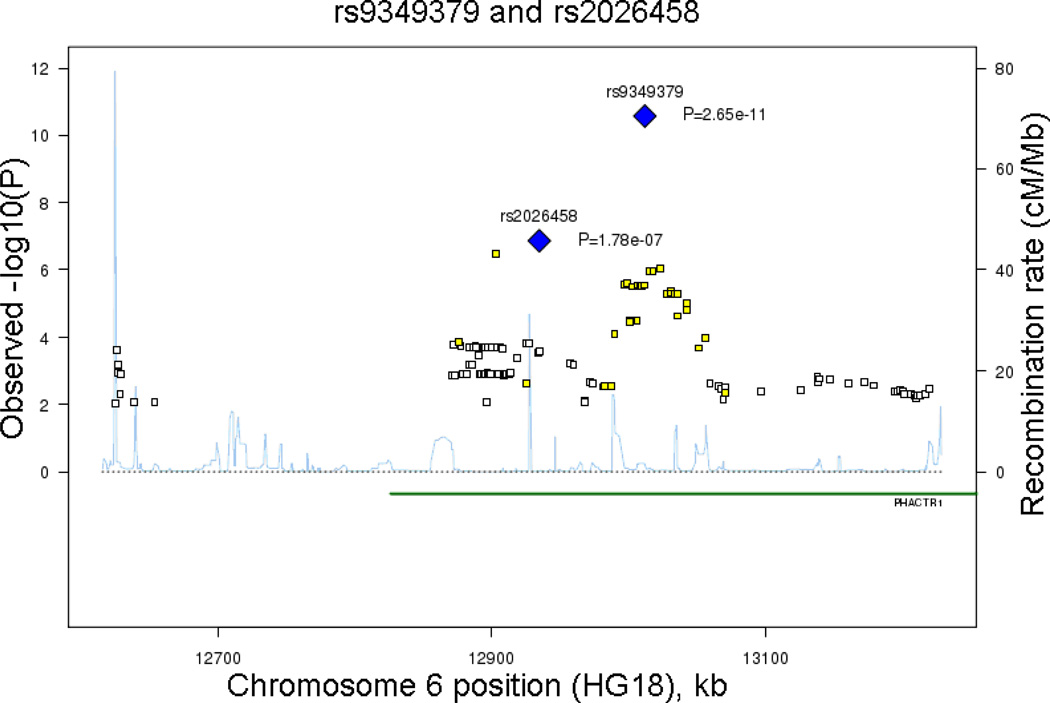

Figure 2.

Observed –log(P) and recombination rates by chromosomal position for all associated SNPs nearby (a) rs1333049 near CDKN2B on 9p21.3 and (b) rs9349379 near PHACTR on 6p24. Results from the genome-wide association analysis of SNPs versus age and sex-adjusted CAC quantity in the meta-analysis of five independent discovery cohorts. Association plots were conducted using SNAP.[27] Top SNPs of interest and P values in each region are indicated (blue diamonds). Color coding indicates the strength of LD of each SNP with the top SNP in each region: red (r2≥0.08), orange (r2≥0.5), yellow (r2≥0.2), white with no color (r2<0.2).

The strong association on 6p24 in the PHACTR1 gene represents a new finding for CAC. The two most strongly associated SNPs, rs9349379 and rs2026458, are modestly correlated (r2=0.37) and reside 78,083 bp apart (Table 2). Figure 2b provides a plot of meta-analysis P-values for SNPs near rs9349379. Supplemental Figures 1a and 1b provide plots of observed –log10(P) versus expected –log10(P) with and without the genome-wide significantly associated SNPs in the analysis.

Table 2 presents results for SNPs in five other loci— COL4A1/COL4A2, SERPINI, HAL, CDC7 and IRS2—moderately associated with CAC quantity. Supplemental Table S3 shows the results for the most strongly associated SNPs in each individual cohort while Supplemental Table S4 presents results of all SNP associations for CAC quantity with P<5×10−6 from the meta-analysis, the associations when those with prior MI are excluded, and the results of tests for homogeneity. The results are similar when those with prior MI are excluded, and there is no evidence for significant heterogeneity. None of the SNPs in Tables 2 or S4 have a p<0.01 for the test for SNP heterogeneity. The results for SNP associations were also similar after adjustment for additional CHD risk factors in addition to age and sex (data not shown).

The results were also similar after adjustment for additional CHD risk factors in addition to age and sex (data not shown). In addition, inferences for the CAC threshold of 100 were similar to those for CAC quantity (Supplemental Table S5).

CAC Replication and Association with MI

Table 3 presents the results in the replication cohorts for the eight SNPs with the strongest association in the discovery cohorts. The meta-analysis P-value for the combined discovery and replication cohorts remained genome-wide significant and lower than the discovery P-value for rs1333049 and rs9349379, and moderately associated (P<1×10−6) for rs2026458 and rs3809346 (COL4A1/COL4A2).

Table 3.

Association of top coronary artery calcification quantity SNPs in replication panel of three cohorts and combined with the discovery cohorts

| SNP | Chr | Position | Closest Reference Gene† |

Distance from Nearest Transcript†† |

Coded allele |

Replication | Discovery + Replication* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P | Beta (SE) | P | ||||||

| rs1333049 | 9 | 22,115,503 | (CDKN2B) | 116,191 | C | 0.147 (0.026) | 1.41 × 10−8 | 0.199 (0.020) | 3.33 × 10−24 |

| rs9349379 | 6 | 13,011,943 | PHACTR1 | 186,125 | A | −0.187 (0.026) | 1.22 × 10−12 | −0.196 (0.020) | 3.90 × 10−22 |

| rs2026458 | 6 | 12,933,860 | PHACTR1 | 108,042 | T | 0.082 (0.026) | 1.73 × 10−3 | 0.115 (0.020) | 8.10 × 10−9 |

| rs3809346 | 13 | 109,758,944 | COL4A2 | 1,313 | A | 0.064 (0.027) | 1.79 × 10−2 | 0.102 (0.021) | 8.64 × 10−7 |

| rs6783981 | 3 | 169,010,823 | SERPINI1 | 15,225 | T | 0.009 (0.026) | 7.26 × 10−1 | −0.054 (0.019) | 5.85 × 10−3 |

| rs17676451 | 12 | 94,899,916 | HAL | 8,644 | A | −0.003 (0.036) | 9.24 × 10−1 | −0.084 (0.026) | 1.12 × 10−3 |

| rs6604023 | 1 | 91,717,485 | (CDC7) | 21,546 | C | 0.051 (0.036) | 1.59 × 10−1 | 0.111 (0.027) | 3.66 × 10−5 |

| rs8001186 | 13 | 109,174,856 | (IRS2) | 29,328 | T | −0.005 (0.028) | 8.59 × 10−1 | −0.068 (0.021) | 1.37 × 10−3 |

Genes for SNPs that are outside the transcript boundary of the protein-coding gene are shown in parentheses [e.g., (CDKN2B)].

Distance in base pairs from nearest start or stop site for transcription.

Combined p-values in bold are below the genome-wide threshold; other combined p-values are not significant at a genome-wide level.

Table 4 presents association of selected SNPs with MI. In addition to known associations near CDKN2B and PHACTR1 with MI, several loci recently reported to be associated with MI,8;11 including rs874203 (intronic SNP in COL4A2), rs6657811 (nearest CELSR2 and also near SORT1), and rs1720819 (near MRAS), had concordant associations (same direction of effect for same allele) with both CAC and MI in our meta-analysis, although the associations were not below a Bonferroni adjusted P-value of 4.3×10−5 (Table 4). When we examined the association of the same SNPs in the GWAS results from the CARDIoGRAM Consortium,14 a total of ten out of 16 SNPs were associated with coronary disease, after Bonferroni adjustment, including the five SNPs above as well as rs380946 (in COL4A2), rs599839 (near PSRC1), and rs1199337 (in MRAS); for the ten SNPs, the direction of effect was the same for CAC and coronary disease (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 4.

Association of top coronary artery calcification quantity SNPs with myocardial infarction in a meta-analysis of four studies

| SNP | Chr | Position | Closest Reference Gene† |

Distance from Nearest Transcrit†† |

Beta Coefficient |

SE | P | Coded Allele Frequency |

Coded Allele |

Non- coded allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associations with P<4.3 × 10−5 | ||||||||||

| rs10811647 | 9 | 22,055,002 | (CDKN2B) | 55,690 | −0.133 | 0.026 | 2.81 × 10−7 | 0.56 | C | G |

| rs9349379* | 6 | 13,011,943 | PHACTR1 | 186,125 | −0.122 | 0.029 | 2.06 × 10−5 | 0.61 | A | G |

| Associations with 4.3 × 10−5 <P<1 × 10−2 | ||||||||||

| rs874203 | 13 | 109,625,575 | COL4A1 | 26,265 | 0.123 | 0.032 | 8.88 × 10−5 | 0.37 | A | T |

| rs6657811 | 1 | 109,608,806 | CELSR2 | 11,095 | 0.148 | 0.043 | 5.92 × 10−4 | 0.88 | A | T |

| rs1720819** | 3 | 139,583,229 | MRAS | 23,838 | −0.125 | 0.040 | 1.91 × 10−3 | 0.89 | T | G |

| rs3809346 | 13 | 109,758,944 | COL4A2 | 1,313 | 0.084 | 0.027 | 1.99 × 10−3 | 0.44 | A | G |

| rs11984041 | 7 | 18,998,460 | HDAC9 | 5,049 | 0.136 | 0.045 | 2.67 × 10−3 | 0.09 | T | C |

| rs13170330 | 5 | 7,498,712 | ADCY2 | 49,370 | −0.098 | 0.033 | 2.96 × 10−3 | 0.24 | A | C |

| rs599839 | 1 | 109,623,689 | (PSRC1) | 12 | 0.089 | 0.031 | 3.86 × 10−3 | 0.77 | A | G |

| rs2330341+ | 7 | 53,173,719 | (DKFZp564N2472) | 101,608 | −0.089 | 0.032 | 5.05 × 10−3 | 0.75 | A | G |

| rs1199337** | 3 | 139,570,754 | MRAS | 20,557 | 0.096 | 0.035 | 5.37 × 10−3 | 0.16 | C | G |

| rs12146493++ | 11 | 65,303,909 | DKFZp761E198 | 489 | −0.074 | 0.027 | 7.38 × 10−3 | 0.33 | A | G |

| rs163189 | 5 | 122,470,526 | (PPIC) | 70,202 | −0.090 | 0.034 | 7.53 × 10−3 | 0.83 | T | C |

| rs1021505 | 5 | 95,377,193 | (ELL2) | 53,662 | 0.080 | 0.031 | 8.59 × 10−3 | 0.66 | A | T |

| rs2026458* | 6 | 12,933,860 | PHACTR1 | 108,042 | 0.071 | 0.027 | 8.67 × 10−3 | 0.44 | T | C |

| rs12772023 | 10 | 108,115,181 | (SORCS1) | 208,230 | 0.307 | 0.119 | 9.82 × 10−3 | 0.02 | T | C |

SNP rs9349379 and rs2026458 reside 78,083 bp apart, (r2 0.374, D’ 0.715).

SNP rs1720819 and rs1199337 reside 12,475 bp apart, (r2 0.483, D’ 1).

Genes for SNPs that are outside the transcript boundary of the protein-coding gene are shown in parentheses [e.g., (CDKN2B)].

Distance in base pairs from nearest start or stop site for transcription.

Hypothetical protein LOC285877

Hypothetical protein LOC91056

Twelve of 14 SNPs strongly associated with MI in recent GWAS were available in the discovery cohorts (Table 5). In addition to the known associations with SNPs in 9p21 and 6p24, four other loci—CXCL12, MRAS, LPA and CELSR2/PSRC1/ SORT1— were associated with CAC quantity (after Bonferroni adjustment for 12 tests). When we examined the association of the 25 SNPs in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium that are significantly associated with coronary disease and available in the our discovery GWAS for CAC, a total of seven out of 25 SNPs were associated with CAC after Bonferroni adjustment, with the same direction of effect for CAC and coronary disease for the seven SNPs (Supplementary Table 7).

Table 5.

Association results for coronary artery calcification quantity for SNPs with strong association with premature onset myocardial infarction.

| SNPs associated with early MI in past GWAS | SNPs associated with CAC in the meta- analysisof five discovery cohorts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC (continuous) | ||||||||

| SNP | Chr | Position | Gene(s) | Risk Allele |

MI GWAS P |

Beta | SE | P |

| rs4977574 | 9 | 220,885,74 | CDKN2A, CDKN2B | G | 2.7 × 10−44 | 0.244 | 0.030 | 3.2 × 10−16 |

| rs12526453 | 6 | 13,035,530 | PHACTR1 | C | 1.3 × 10−9 | 0.137 | 0.033 | 2.2 × 10−5 |

| rs1746048 | 10 | 44,096,080 | CXCL12 | C | 7.4 × 10−9 | 0.141 | 0.044 | 1.5 × 10−3 |

| rs9818870 | 3 | 139,604,812 | MRAS | T | 7.4 × 10−13 | 0.131 | 0.042 | 1.8 × 10−3 |

| rs10455872 | 6 | 160,930,108 | LPA | G | 3.4 × 10−15 | 0.225 | 0.075 | 2.8 × 10−3 |

| rs646776 | 1 | 109,620,303 | CELSR2, PSRC1, SORT1 | T | 7.9 × 10−12 | 0.127 | 0.037 | 5.3 × 10−4 |

| rs6725887 | 2 | 203,454,380 | WDR12 | C | 1.3 × 10−8 | 0.077 | 0.046 | 0.09 |

| rs1122608 | 19 | 11,024,851 | LDLR | G | 1.9 × 10−9 | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.10 |

| rs9982601 | 21 | 34,521,248 | SLC5A3, MRPS6, KCNE2 | T | 6.4 × 10−11 | 0.055 | 0.044 | 0.21 |

| rs11206510 | 1 | 55,268,877 | PCSK9 | T | 9.6 × 10−9 | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.62 |

| rs3184504 | 12 | 110,368,991 | SH2B3 | T | 8.6 × 10−8 | −0.010 | 0.031 | 0.75 |

| rs2259816 | 12 | 119,919,970 | HNF1A | T | 4.8 × 10−7 | −0.007 | 0.031 | 0.81 |

Abbreviations: MI=myocardial infarction; GWAS=genome-wide association study; Beta=beta coefficient; SE=standard error; CAC=coronary artery calcification; NA=not available.

Discussion

Our replicated CAC association of rs1333049 on chromosome 9p21 and our novel replicated associations of rs93493979 on 6p24 (the PHACTR1 locus), as well as the strong evidence for association in the combined discovery and replication cohorts for rs2026458, provides evidence these loci contribute to variation in coronary atherosclerotic calcified plaque. Although both loci have been associated with MI, and now with CAC, the specific causal variants have not been elucidated for either locus and our GWA study is not able to provide evidence for causal association with nearby genes. SNPs in 9p21 reside over 100,000 bp away from, and are poorly correlated (ie., in low LD) with the nearest protein-coding genes, the cell cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors CKDN2B and CDKN2A. SNPs associated with both CAC and MI overlap with the upstream portion of a newly annotated antisense noncoding RNA (also known as ANRIL or DQ485453).29 The mechanism of association of ANRIL is not known; however, the strength and consistency of SNP associations with CAC and MI strongly suggest involvement in formation of calcified atherosclerotic lesions in coronary arteries.

A recent report implicates the 9p21 risk interval in regulation of cardiac CDKN2A/B expression, suggesting this region may affect atherosclerosis progression via vascular cell proliferation.30 Of note, SNPs in this region are also strongly associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms31;32 and vascular stiffness,33 but not with carotid intimal medial wall thickness determined by ultrasonography.33;34

Our newly identified association between CAC and PHACTR1 SNPs, similar to the association between MI and these SNPs, may represent a novel pathway for development of clinical atherosclerosis. PHACTR1 in 6p24 is an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1, a ubiquitous serine/threonine phosphatase known to regulate multiple cellular processes through dephosphorylation of different substrates.35 The exact mechanism of association of this locus or pathway with CAC and MI is unknown.

In addition, SNPs on 3q22.3 near MRAS, on 1p13 near CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1, and in CXCL12 and LPA showed concordant association with CAC and MI, although the CAC associations did not reach genome-wide significance.8;11 The M-ras protein encoded by MRAS (3q22) belongs to the ras superfamily of GTP-binding proteins and is expressed in the heart and aorta,8 and may be involved in adhesion signaling, which is important in the atherosclerotic process.36 The locus containing the CELSR2 (cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 2) gene also harbors PSRC1 and SORT1. In recent very large GWA study, as in prior smaller GWA studies, SNPs in this locus were shown to be associated with MI and with circulating LDL-cholesterol levels.37 In previous work, rs646776, which is highly correlated with rs6657811 (D′ = 0.93), was strongly associated with human liver transcript concentrations of the three nearby genes, SORT1, CELSR2, and PSRC1.38 In our CAC meta-analysis, rs646776 had the same direction of effect with continuous CAC (P=5.3 × 10−4) and with CAC >100 (P=1.6 × 10−3) as reported for MI (data not shown). A recent investigation, incorporating both mouse and human models, demonstrated that a nearby common noncoding polymorphism at the 1p13 locus (rs12740374, D’=1.0) serves as a proxy for rs646776 directly implicates hepatic SORT1 gene expression in the causal mechanism of altered plasma LDL and risk for MI.39 These findings are consistent with a genetic component to the association of LDL-cholesterol levels with both CAC and MI.

A new and potentially interesting finding is the concordant association with SNPs in the COL4A1/COL4A2 locus at 13q34. While not reaching genome wide significance, the region was moderately associated with both CAC and clinically apparent MI. Importantly, COL4A1/COL4A2 is a new gene identified in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium.14 Type IV collagen is a basement-membrane collagen that does not form ordered fibrillar structures but instead forms 4 molecules crosslinked together at the ends. The COL4A1 and COL4A2 genes are transcribed divergently by the same promoter. Mutations in COL4A1 have been implicated in several rare familial conditions including porencephaly, manifested by cystic cavities of the brain;40 small arterial vessel disease and cerebral hemmorhage;41 and a syndrome including hereditary angiopathy, nephropathy, and aneurysms.42 A recent GWA study for vascular stiffness measures reported a strong replicated association of SNPs in COL4A1 with arterial stiffness.43 A prior candidate gene case-control study in Japan provided the first unreplicated report of an association of SNPs in COL4A1 with MI at a modest level of significance (P<0.05).44 While to date there have been no reports of common variants in the COL4A1/COL4A2 locus having genome-wide significant associations with CAC, our findings for CAC taken together with findings from the CARDIoGRAM consortium provide evidence in support of a role for variants in this locus in both coronary atherosclerosis and clinically apparent MI.

Not all individuals with high CAC quantity develop MI and some cases of MI occur in the absence of high levels of CAC.2;6;7 In comparing SNPs for MI with the CAC GWA, we note there is evidence for association of one other SNP reported to be associated with MI, rs174604811 near CXCL12 on 10q11.21 (P=1.5×10−3 in our CAC GWA meta-analysis). In contrast, there was no evidence for association with CAC quantity of several other SNPs associated with MI, including SNPs on 2q33.1 near WDR12, 19p13.2 near LDLR, 21q22.1 near KCNE2, 1p32.3 near PCSK9, 12q24.1 near SH2B3 and 12q24.3 near HFN1A (Table 5). rs17465637 on 1q41 near MIA3 was not assessed in our meta-analysis as it is not localized in HapMap, although there are non-significant associations with CAC quantity of SNPs within a 25,000 bp interval (e.g., rs17011666, P=0.0098). When we examined the association of the 25 SNPs in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium that are significantly associated with coronary disease and available in our discovery GWAS for CAC, a total of seven out of 25 SNPs were associated with CAC after Bonferroni adjustment, including SNPs in 9p21 and 6p24 as well as SNPs near CXCL12, SORT1, MRAS, COL4A1/COL4A2, and ADAMTS7; the remainder of the 25 SNPs were not significantly associated with CAC quantity (Supplementary Table 7). The absence of a genetic association may be due to limited power or confounding factors. However, the fact that some loci are risk factors for both CAC and CAD and others are not raises the possibility that some, but not all, genetic mechanisms for CAD are strongly related to the presence and burden of coronary atherosclerosis. It is notable that a recent report of a GWAS for coronary atherosclerosis detected by angiograpy in selected cases of diseased patients reported novel GWA associations with ADAMTS7 and ABO and also reported concordance of association with several other loci including 9p21, PHACTR1, MRAS and SORT1.45

Strengths of the present study include data from large community-based studies, similarity in CAC assessment and quality control measures across cohorts, as well as similarity in imputation strategies and analytical methods. Limitations include heterogeneity in the cohorts and differences in actual CT scanners. Moreover, we have modest statistical power to detect associations with low frequency SNPs or poorly imputed SNPs. This limitation in power may have impacted our ability to identify additional SNPs associated with both CAC and MI. Examination of larger cohorts with CAC may detect more genome-wide significant associations. In addition, identified associations with genomic regions require further follow-up studies to establish the actual functional variants and elucidate actual mechanisms of association. Finally, we cannot generalize our findings to individuals of non-European ancestry.

The associations of SNPs in 9p21 and 6p24 in the discovery and replication studies for CAC and in the MI studies, as well as the association with SNPs in or near other genes including MRAS, COL4A1/COL4A2, and SORT1, suggest that the common mechanism of some genetic loci underlying MI is development of early, underlying coronary atherosclerosis. Investigations to understand mechanisms underlying the genetic associations with coronary atherosclerosis may ultimately suggest new strategies for prediction, prevention and treatment of CHD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

See Separate Supplemental Materials.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Ziegler reports receiving honoraria and ownership interest >$10K. Dr’s. Rotter, Murabito, Borecki, Bielack, Kardia, and Witteman report receiving government research grants relevant to the research topic. No other co-author has reported a conflict.

Reference List

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern SM, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wilson M, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, Budoff MJ, Eisenberg MJ, Grundy SM, Lauer MS, Post WS, Raggi P, Redberg RF, Rodgers GP, Shaw LJ, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS, Harrington RA, Abrams J, Anderson JL, Bates ER, Grines CL, Hlatky MA, Lichtenberg RC, Lindner JR, Pohost GM, Schofield RS, Shubrooks SJ, Jr, Stein JH, Tracy CM, Vogel RA, Wesley DJ. ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Consensus Task Force (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Consensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography) Circulation. 2007;115:402–426. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA..107.181425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peyser PA, Bielak LF, Chu JS, Turner ST, Ellsworth DL, Boerwinkle E, Sheedy PF. Heritability of coronary artery calcium quantity measured by electron beam computed tomography in asymptomatic adults. Circulation. 2002;106:304–308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022664.21832.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, Cupples LA, Fox CS, Manders ES, Murabito JM, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, O'Donnell CJ. Parental occurrence of premature cardiovascular disease predicts increased coronary artery and abdominal aortic calcification in the Framingham Offspring and Third Generation cohorts. Circulation. 2007;116:1473–1481. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.705202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Rourke RA, Brundage BH, Froelicher VF, Greenland P, Grundy SM, Hachamovitch R, Pohost GM, Shaw LJ, Weintraub WS, Winters WL., Jr American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Expert Consensus Document on electron-beam computed tomography for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:326–340. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vliegenthart R, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Oei HH, van DW, van Rooij FJ, Witteman JC. Coronary calcification improves cardiovascular risk prediction in the elderly. Circulation. 2005;112:572–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.488916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Bluemke DA, O'Leary DH, Tracy R, Watson K, Wong ND, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdmann J, Grosshennig A, Braund PS, Konig IR, Hengstenberg C, Hall AS, Linsel-Nitschke P, Kathiresan S, Wright B, Tregouet DA, Cambien F, Bruse P, Aherrahrou Z, Wagner AK, Stark K, Schwartz SM, Salomaa V, Elosua R, Melander O, Voight BF, O'Donnell CJ, Peltonen L, Siscovick DS, Altshuler D, Merlini PA, Peyvandi F, Bernardinelli L, Ardissino D, Schillert A, Blankenberg S, Zeller T, Wild P, Schwarz DF, Tiret L, Perret C, Schreiber S, El Mokhtari NE, Schafer A, Marz W, Renner W, Bugert P, Kluter H, Schrezenmeir J, Rubin D, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ, Wichmann HE, Meitinger T, Fischer M, Meisinger C, Baumert J, Peters A, Ouwehand WH, Deloukas P, Thompson JR, Ziegler A, Samani NJ, Schunkert H. New susceptibility locus for coronary artery disease on chromosome 3q22.3. Nat Genet. 2009;41:280–282. doi: 10.1038/ng.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Gretarsdottir S, Blondal T, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Sigurdsson A, Baker A, Palsson A, Masson G, Gudbjartsson D, Magnusson KP, Andersen K, Levey AI, Backman VM, Matthiasdottir S, Jonsdottir T, Palsson S, Einarsdottir H, Gunnarsdottir S, Gylfason A, Vaccarino V, Hooper WC, Reilly MP, Granger CB, Austin H, Rader DJ, Shah SH, Quyyumi AA, Gulcher JR, Thorgeirsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. A Common Variant on Chromosome 9p21 Affects the Risk of Myocardial Infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Pennacchio LA, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. A Common Allele on Chromosome 9 Associated with Coronary Heart Disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Hengstenberg C, Mangino M, Mayer B, Dixon RJ, Meitinger T, Braund P, Wichmann HE, Barrett JH, Konig IR, Stevens SE, Szymczak S, Tregouet DA, Iles MM, Pahlke F, Pollard H, Lieb W, Cambien F, Fischer M, Ouwehand W, Blankenberg S, Balmforth AJ, Baessler A, Ball SG, Strom TM, Braenne I, Gieger C, Deloukas P, Tobin MD, Ziegler A, Thompson JR, Schunkert H. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, Preuss M, Stewart AF, Barbalic M, Gieger C, Absher D, Aherrahrou Z, Allayee H, Altshuler D, Anand SS, Andersen K, Anderson JL, Ardissino D, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ, Barnes TA, Becker DM, Becker LC, Berger K, Bis JC, Boekholdt SM, Boerwinkle E, Braund PS, Brown MJ, Burnett MS, Buysschaert I, Carlquist JF, Chen L, Cichon S, Codd V, Davies RW, Dedoussis G, Dehghan A, Demissie S, Devaney JM, Diemert P, Do R, Doering A, Eifert S, Mokhtari NE, Ellis SG, Elosua R, Engert JC, Epstein SE, de FU, Fischer M, Folsom AR, Freyer J, Gigante B, Girelli D, Gretarsdottir S, Gudnason V, Gulcher JR, Halperin E, Hammond N, Hazen SL, Hofman A, Horne BD, Illig T, Iribarren C, Jones GT, Jukema JW, Kaiser MA, Kaplan LM, Kastelein JJ, Khaw KT, Knowles JW, Kolovou G, Kong A, Laaksonen R, Lambrechts D, Leander K, Lettre G, Li M, Lieb W, Loley C, Lotery AJ, Mannucci PM, Maouche S, Martinelli N, McKeown PP, Meisinger C, Meitinger T, Melander O, Merlini PA, Mooser V, Morgan T, Muhleisen TW, Muhlestein JB, Munzel T, Musunuru K, Nahrstaedt J, Nelson CP, Nothen MM, Olivieri O, Patel RS, Patterson CC, Peters A, Peyvandi F, Qu L, Quyyumi AA, Rader DJ, Rallidis LS, Rice C, Rosendaal FR, Rubin D, Salomaa V, Sampietro ML, Sandhu MS, Schadt E, Schafer A, Schillert A, Schreiber S, Schrezenmeir J, Schwartz SM, Siscovick DS, Sivananthan M, Sivapalaratnam S, Smith A, Smith TB, Snoep JD, Soranzo N, Spertus JA, Stark K, Stirrups K, Stoll M, Tang WH, Tennstedt S, Thorgeirsson G, Thorleifsson G, Tomaszewski M, Uitterlinden AG, van Rij AM, Voight BF, Wareham NJ, Wells GA, Wichmann HE, Wild PS, Willenborg C, Witteman JC, Wright BJ, Ye S, Zeller T, Ziegler A, Cambien F, Goodall AH, Cupples LA, Quertermous T, Marz W, Hengstenberg C, Blankenberg S, Ouwehand WH, Hall AS, Deloukas P, Thompson JR, Stefansson K, Roberts R, Thorsteinsdottir U, O'Donnell CJ, McPherson R, Erdmann J, Samani NJ. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psaty BM, O'Donnell CJ, Gudnason V, Lunetta KL, Folsom AR, Rotter JI, Uitterlinden AG, Harris TB, Witteman JCM, Boerwinkle E on behalf of the CHARGE Consortium. Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium: Design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from five cohorts. Circulation Genetics. 2008;2:73–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, Kjartansson O, Jonsson PV, Sigurdsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Aspelund T, Garcia ME, Cotch MF, Hoffman HJ, Gudnason V. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigurdsson E, Thorgeirsson G, Sigvaldason H, Sigfusson N. Unrecognized myocardial infarction: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and the prognostic role of angina pectoris. The Reykjavik Study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:96–102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-2-199501150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;107:539–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Fox CS, Larson MG, Murabito JM, O'Donnell CJ, Vasan RS, Wolf PA, Levy D. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofman A, Breteler MM, van Duijn CM, Janssen HL, Krestin GP, Kuipers EJ, Stricker BH, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Vingerling JR, Witteman JC. The Rotterdam Study: 2010 objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:553–572. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Multi-center genetic study of hypertension. The Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP) Hypertension. 2002;39:3–9. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniell AL, Wong ND, Friedman JD, Ben-Yosef N, Miranda-Peats R, Hayes SW, Kang X, Sciammarella MG, de YL, Germano G, Berman DS. Concordance of coronary artery calcium estimates between MDCT and electron beam tomography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1542–1545. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao SS, Pal RS, McKay CR, Gao YG, Gopal A, Ahmadi N, Child J, Carson S, Takasu J, Sarlak B, Bechmann D, Budoff MJ. Comparison of coronary artery calcium scores between electron beam computed tomography and 64-multidetector computed tomographic scanner. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:175–178. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31817579ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, Benjamin EJ, Budoff MJ, Fayad ZA, Foster E, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Kushner FG, Lauer MS, Shaw LJ, Smith SC, Jr, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS, Wenger NK, Jacobs AK. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2010;122:e584–e636. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182051b4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O'Donnell CJ, de Bakker PI. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blankenberg S, Rupprecht HJ, Bickel C, Torzewski M, Hafner G, Tiret L, Smieja M, Cambien F, Meyer J, Lackner KJ. Glutathione peroxidase 1 activity and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1605–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Cho H, Burd CE, Torrice C, Mohlke KL, Ibrahim JG, Thomas NE, Sharpless NE. INK4/ARF transcript expression is associated with chromosome 9p21 variants linked to atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Visel A, Zhu Y, May D, Afzal V, Gong E, Attanasio C, Blow MJ, Cohen JC, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. Targeted deletion of the 9p21 non-coding coronary artery disease risk interval in mice. Nature. 2010;464:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nature08801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Magnusson KP, Gretarsdottir S, Steinthorsdottir V, Manolescu A, Jones GT, Rinkel GJ, Blankensteijn JD, Ronkainen A, Jaaskelainen JE, Kyo Y, Lenk GM, Sakalihasan N, Kostulas K, Gottsater A, Flex A, Stefansson H, Hansen T, Andersen G, Weinsheimer S, Borch-Johnsen K, Jorgensen T, Shah SH, Quyyumi AA, Granger CB, Reilly MP, Austin H, Levey AI, Vaccarino V, Palsdottir E, Walters GB, Jonsdottir T, Snorradottir S, Magnusdottir D, Gudmundsson G, Ferrell RE, Sveinbjornsdottir S, Hernesniemi J, Niemela M, Limet R, Andersen K, Sigurdsson G, Benediktsson R, Verhoeven EL, Teijink JA, Grobbee DE, Rader DJ, Collier DA, Pedersen O, Pola R, Hillert J, Lindblad B, Valdimarsson EM, Magnadottir HB, Wijmenga C, Tromp G, Baas AF, Ruigrok YM, van Rij AM, Kuivaniemi H, Powell JT, Matthiasson SE, Gulcher JR, Thorgeirsson G, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. The same sequence variant on 9p21 associates with myocardial infarction, abdominal aortic aneurysm and intracranial aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2008;40:217–224. doi: 10.1038/ng.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson AR, Golledge J, Cooper JA, Hafez H, Norman PE, Humphries SE. Sequence variant on 9p21 is associated with the presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm disease but does not have an impact on aneurysmal expansion. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:391–394. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorck HM, Lanne T, Alehagen U, Persson K, Rundkvist L, Hamsten A, Dahlstrom U, Eriksson P. Association of genetic variation on chromosome 9p21.3 and arterial stiffness. J Intern Med. 2009;265:373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunnington MS, Mayosi BM, Hall DH, Avery PJ, Farrall M, Vickers MA, Watkins H, Keavney B. Novel genetic variants linked to coronary artery disease by genome-wide association are not associated with carotid artery intima-media thickness or intermediate risk phenotypes. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen PB, Greenfield AT, Svenningsson P, Haspeslagh DC, Greengard P. Phactrs 1–4: A family of protein phosphatase 1 and actin regulatory proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7187–7192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401673101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galkina E, Ley K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2292–2301. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, Johansen CT, Fouchier SW, Isaacs A, Peloso GM, Barbalic M, Ricketts SL, Bis JC, Aulchenko YS, Thorleifsson G, Feitosa MF, Chambers J, Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Johnson T, Li X, Guo X, Li M, Shin CY, Jin GM, Jin KY, Lee JY, Park T, Kim K, Sim X, Twee-Hee OR, Croteau-Chonka DC, Lange LA, Smith JD, Song K, Hua ZJ, Yuan X, Luan J, Lamina C, Ziegler A, Zhang W, Zee RY, Wright AF, Witteman JC, Wilson JF, Willemsen G, Wichmann HE, Whitfield JB, Waterworth DM, Wareham NJ, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Voight BF, Vitart V, Uitterlinden AG, Uda M, Tuomilehto J, Thompson JR, Tanaka T, Surakka I, Stringham HM, Spector TD, Soranzo N, Smit JH, Sinisalo J, Silander K, Sijbrands EJ, Scuteri A, Scott J, Schlessinger D, Sanna S, Salomaa V, Saharinen J, Sabatti C, Ruokonen A, Rudan I, Rose LM, Roberts R, Rieder M, Psaty BM, Pramstaller PP, Pichler I, Perola M, Penninx BW, Pedersen NL, Pattaro C, Parker AN, Pare G, Oostra BA, O'Donnell CJ, Nieminen MS, Nickerson DA, Montgomery GW, Meitinger T, McPherson R, McCarthy MI, McArdle W, Masson D, Martin NG, Marroni F, Mangino M, Magnusson PK, Lucas G, Luben R, Loos RJ, Lokki ML, Lettre G, Langenberg C, Launer LJ, Lakatta EG, Laaksonen R, Kyvik KO, Kronenberg F, Konig IR, Khaw KT, Kaprio J, Kaplan LM, Johansson A, Jarvelin MR, Cecile JWJ, Ingelsson E, Igl W, Kees HG, Hottenga JJ, Hofman A, Hicks AA, Hengstenberg C, Heid IM, Hayward C, Havulinna AS, Hastie ND, Harris TB, Haritunians T, Hall AS, Gyllensten U, Guiducci C, Groop LC, Gonzalez E, Gieger C, Freimer NB, Ferrucci L, Erdmann J, Elliott P, Ejebe KG, Doring A, Dominiczak AF, Demissie S, Deloukas P, de Geus EJ, de FU, Crawford G, Collins FS, Chen YD, Caulfield MJ, Campbell H, Burtt NP, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Boekholdt SM, Bergman RN, Barroso I, Bandinelli S, Ballantyne CM, Assimes TL, Quertermous T, Altshuler D, Seielstad M, Wong TY, Tai ES, Feranil AB, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS, Taylor HA, Jr, Borecki IB, Gabriel SB, Wilson JG, Holm H, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudnason V, Krauss RM, Mohlke KL, Ordovas JM, Munroe PB, Kooner JS, Tall AR, Hegele RA, Kastelein JJ, Schadt EE, Rotter JI, Boerwinkle E, Strachan DP, Mooser V, Stefansson K, Reilly MP, Samani NJ, Schunkert H, Cupples LA, Sandhu MS, Ridker PM, Rader DJ, van Duijn CM, Peltonen L, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Kathiresan S. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, Kaplan L, Bennett D, Li Y, Tanaka T, Voight BF, Bonnycastle LL, Jackson AU, Crawford G, Surti A, Guiducci C, Burtt NP, Parish S, Clarke R, Zelenika D, Kubalanza KA, Morken MA, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Galan P, Swift AJ, Kuusisto J, Bergman RN, Sundvall J, Laakso M, Ferrucci L, Scheet P, Sanna S, Uda M, Yang Q, Lunetta KL, Dupuis J, de Bakker PI, O'Donnell CJ, Chambers JC, Kooner JS, Hercberg S, Meneton P, Lakatta EG, Scuteri A, Schlessinger D, Tuomilehto J, Collins FS, Groop L, Altshuler D, Collins R, Lathrop GM, Melander O, Salomaa V, Peltonen L, Orho-Melander M, Ordovas JM, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Mohlke KL, Cupples LA. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Lee NE, Ahfeldt T, Sachs KV, Li X, Li H, Kuperwasser N, Ruda VM, Pirruccello JP, Muchmore B, Prokunina-Olsson L, Hall JL, Schadt EE, Morales CR, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Wong J, Cantley W, Racie T, Ejebe KG, Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Koteliansky V, Fitzgerald K, Krauss RM, Cowan CA, Kathiresan S, Rader DJ. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gould DB, Phalan FC, Breedveld GJ, van Mil SE, Smith RS, Schimenti JC, Aguglia U, van der Knaap MS, Heutink P, John SW. Mutations in Col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science. 2005;308:1167–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1109418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gould DB, Phalan FC, van Mil SE, Sundberg JP, Vahedi K, Massin P, Bousser MG, Heutink P, Miner JH, Tournier-Lasserve E, John SW. Role of COL4A1 in small-vessel disease and hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1489–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plaisier E, Gribouval O, Alamowitch S, Mougenot B, Prost C, Verpont MC, Marro B, Desmettre T, Cohen SY, Roullet E, Dracon M, Fardeau M, Van AT, Kerjaschki D, Antignac C, Ronco P. COL4A1 mutations and hereditary angiopathy, nephropathy, aneurysms, and muscle cramps. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2687–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarasov KV, Sanna S, Scuteri A, Strait JB, Orru M, Parsa A, Lin PI, Maschio A, Lai S, Piras MG, Masala M, Tanaka T, Post W, O'Connell JR, Schlessinger D, Cao A, Nagaraja R, Mitchell BD, Abecasis GR, Shuldiner AR, Uda M, Lakatta EG, Najjar SS. COL4A1 is associated with arterial stiffness by genome-wide association scan. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:151–158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.823245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada Y, Kato K, Oguri M, Fujimaki T, Yokoi K, Matsuo H, Watanabe S, Metoki N, Yoshida H, Satoh K, Ichihara S, Aoyagi Y, Yasunaga A, Park H, Tanaka M, Nozawa Y. Genetic risk for myocardial infarction determined by polymorphisms of candidate genes in a Japanese population. J Med Genet. 2008;45:216–221. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reilly MP, Li M, He J, Ferguson JF, Stylianou IM, Mehta NN, Burnett MS, Devaney JM, Knouff CW, Thompson JR, Horne BD, Stewart AF, Assimes TL, Wild PS, Allayee H, Nitschke PL, Patel RS, Martinelli N, Girelli D, Quyyumi AA, Anderson JL, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Schunkert H, Quertermous T, Blankenberg S, Hazen SL, Roberts R, Kathiresan S, Samani NJ, Epstein SE, Rader DJ. Identification of ADAMTS7 as a novel locus for coronary atherosclerosis and association of ABO with myocardial infarction in the presence of coronary atherosclerosis: two genome-wide association studies. Lancet. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.