Abstract

The CK2 α and α′ catalytic gene products have overlapping biochemical activity, but in vivo, their functions are very different. Deletion of both alleles of CK2α leads to mid-gestational embryonic lethality, while deletion of both alleles of CK2α′ does not interfere with viability or development of embryos; however, adult CK2α′ −/−males are infertile. To further elucidate developmental roles of CK2, and analyze functional overlap between the two catalytic genes, mice with combined knockouts were bred. Mice bearing any two CK2 catalytic alleles were phenotypically normal. However, inheritance of a single CK2α allele, without either CK2α′ allele, resulted in partial embryonic lethality. Such mice that survived through embryogenesis were smaller at birth than littermate controls, and weighed less throughout life. However, their cardiac function and lifespan were normal. Fibroblasts derived from CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− embryos grew poorly in culture. These experiments demonstrate that combined loss of one CK2α allele and both CK2α′ alleles leads to unique abnormalities of growth and development.

Keywords: Protein kinase CK2, Casein kinase II, Homologous recombination, Mouse embryonic fibroblast

Introduction

CK2 is a tetrameric serine-threonine kinase that is ubiquitously expressed and highly conserved, highlighting its important role in vivo. It has been described as targeting hundreds of substrates, and has been shown to regulate a multitude of pathways in cells, ranging from DNA replication and repair, transcriptional control, RNA translation, and protein–protein interactions, trafficking, signaling, and stability [1–3]. Overexpressed CK2 promotes tumorigenesis, through activation of Wnt and other signaling pathways [4, 5]. Recent studies have explored CK2 as a druggable target for therapy of cancer and other diseases [6–9].

In an attempt to determine the essential roles of CK2 in vivo, we have engineered mice in which genes encoding the catalytic subunits of CK2, CK2α on mouse chromosome 2 and CK2α′ on mouse chromosome 8, are missing. CK2α and CK2α′ are highly homologous, with approximately 90% sequence identity in the N- terminal 330 amino acids, and divergence in the C-terminal extension found on CK2α [10]. While a variety of experiments have suggested there might be different physiological roles for the two catalytic subunits, and the holoenzymes comprised of either two alpha subunits, two alpha-prime subunits, or one of each, in fact in most in vitro assays and on most substrates, the activity of the two subunits is identical [11, 12].

Genetic experiments however, suggest there may be marked differences in vivo. Mice in which a single subunit of CK2α or CK2α′ is eliminated by homologous recombination are phenotypically undistinguishable from wild type animals. However, mice in which CK2α is entirely absent are non-viable, dying in mid-gestation with a variety of defects of organ and tissue development [13]. Undoubtedly, cardiac defects are responsible for death of the embryos (Dominguez et al., elsewhere in this volume). On the other hand, mice lacking all CK2α′ develop normally and survive into adulthood. The major abnormality of CK2α′ homozygous knockout mice is infertility of the males. The male mice have oligospermia, and the sperm that do make it to maturity have abnormal round heads (globozoospermia) and kinked or broken tails, rendering them dysmotile [14]. This defect may reflect a unique biochemical property of CK2α′ protein, or could just reflect its domain of normal expression: it is highly expressed in maturing spermatozoa; its loss there may not be compensated by residual CK2α. This conundrum can be addressed genetically. Here we sought to investigate the combined role of both CK2 catalytic subunits at the organismal level. We bred mice that lack combinations of CK2 catalytic subunits and compared their phenotypes.

Materials and methods

All mouse experiments were done with the approval of the IACUC at Boston University Medical Campus. Mice were maintained in an AAALAC-approved specific-pathogen free facility. Genotyping for null CK2α and CK2α′ alleles was carried out as described [13, 14], by PCR of DNA derived from tail biopsy specimens. Mice were observed bi-weekly and weighed using a pan balance. Mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) lines were established from embryonic day 13 embryos, and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. To assess their doubling time, MEFs were counted and plated at equal density and passaged every 3–4 days at the same density to determine the cumulative cell number. To measure the expression of the CK2 subunits, subconfluent cells were lysed in NP40-containing buffer and proteins were extracted. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against CK2α, CK2β (Becton–Dickinson), or CK2α′ (Abcam).

Results

The known phenotypes of mice deficient in CK2 catalytic gene subunits are summarized in Table 1. The experiments described below were designed to fill in the unknowns in the Table. Moreover, these experiments could elucidate additional activities of CK2 in vivo and shed light on the functional overlap between CK2α and CK2α′. As illustrated by Table 2, if CK2α and CK2α′ have no overlapping activity in vivo, combined loss of catalytic alleles will result in phenotypes that are the sum of the individual allele knockouts. On the other hand, if their activity and expression pattern are completely overlapping, their effects will be additive; for example, since males lacking two CK2α′ alleles are infertile, in this circumstance, males lacking one CK2α allele and one CK2α′ allele will probably also be infertile. The last possibility described in Table 2 is partial overlap in activity, expression pattern, or function, leading to some compensation in vivo, but possibly new and unexpected effects when combinations of alleles are deleted. Our results suggest that the latter is the case. In fact, to generate the cohort of mice described below, we used CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/−double heterozygous males, and in spite of the lack of two catalytic subunits of CK2, their fertility was not impaired compared to wild type males.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of mice with varying CK2 genotypes

| α | α | α′ | α′ | Name | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | + | + | + | WT | Normal |

| + | + | + | − | α′ Het | Normal |

| + | − | + | + | α Het | Normal |

| + | + | − | − | α′ KO | Male infertility |

| + | − | + | − | Double het | ? |

| + | − | − | − | Single α | ? |

| − | − | + | + | α KO | Embryonic lethal |

Table 2.

Possible outcomes of compound KO genotypes depending upon functional overlap of CK2α and α′

|

Independent targets | |

| Double het | No phenotype | |

| Single α | Male infertile | |

|

Complete identity | |

| Double het | Male infertility | |

| Single α | Lethality | |

|

Partial overlap | |

| Double het | A phenotype | |

| Single α | A new phenotype |

To determine the overlapping and distinct genetic effects of CK2α and CK2α′, compound CK2 knockout mice were generated by breeding male CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/− and female CK2α+/+CK2α′ −/− mice. Possible genotypes of offspring are CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/−, CK2α+/+CK2α′ −/−, CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/−, and CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/−, which by Mendelian inheritance are each expected to be present in 25% of progeny. However, of the 217 offspring, only 24 CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice were identified at weaning (11%) rather than 54 (25%) as expected. The likelihood of this occurring by chance is 1:10−5 by χ2 analysis. However, 25% of MEFs generated from embryos harvested at embryonic day 13 were of the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− genotype, suggesting that embryonic lethality occurs after this time point in gestation.

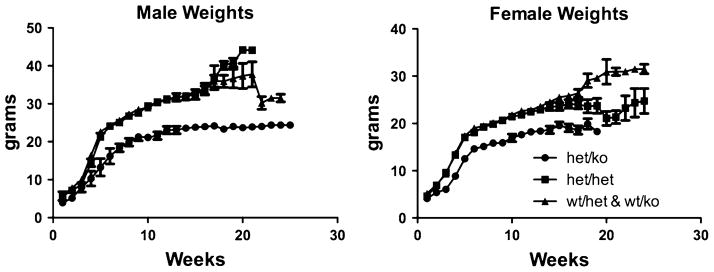

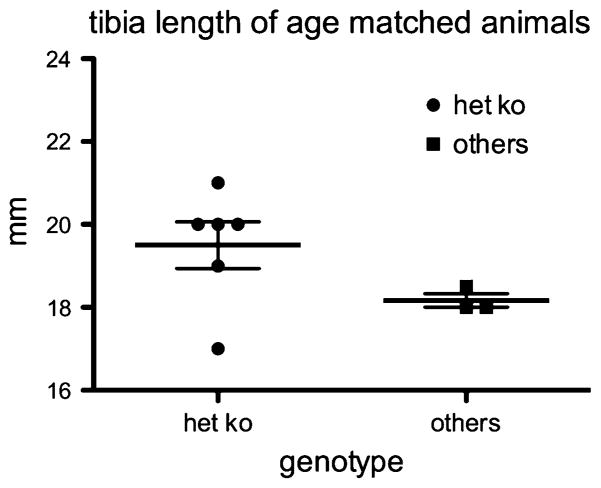

The CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− pups were noted to be smaller than littermates at the time of weaning. Mice were weighed twice weekly from weaning through 6 months of age. The CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice weighed less throughout this period of time (Fig. 1). The differences in weight were significant, comparing CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice to mice of other genotypes. For example, at 16 weeks of age, the mean weight for males with one CK2α allele only was 25 g compared with 33 g for other genotypes (P = 0.0143); for the 16 week females it was 20 g compared with 24 g (P = 0.018). These data indicate that the small size at weaning was not due to competition in the pre-weaning period or to a nursing problem, as it persisted when the mice were fed a standard mouse chow diet. Additionally, we found no evidence of a difference in skeletal development underlying the difference in weight, as tibia length was not significantly reduced in adult CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice compared with controls (Fig. 2).These data indicate that the adult mice differ in weight but not size, which could be a reflection of a reduction in lean muscle mass or of body fat. To assess body composition, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis was performed in the BUMC Small Animal Metabolic Core Facility. In preliminary experiments, the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice were found to have about 50% of the body fat compared to mice of the other genotypes, with no reduction in food intake (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Body weights in the cohort of mice under study. Mice are grouped by genotype. Mice were weighed twice weekly until approximately 6 months of age.

Wt/het: CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/−; wt/ko: CK2α+/+CK2α′ −/−; het/het: CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/−; het/ko: CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/−

Fig. 2.

Tibia length of adult mice. Tibias were measured at necropsy in mice over 1 year old. “Het ko” refers to mice of the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− genotype, while “others” refers to mice of CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/−, CK2α+/+CK2α′ −/−, or CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/−genotypes

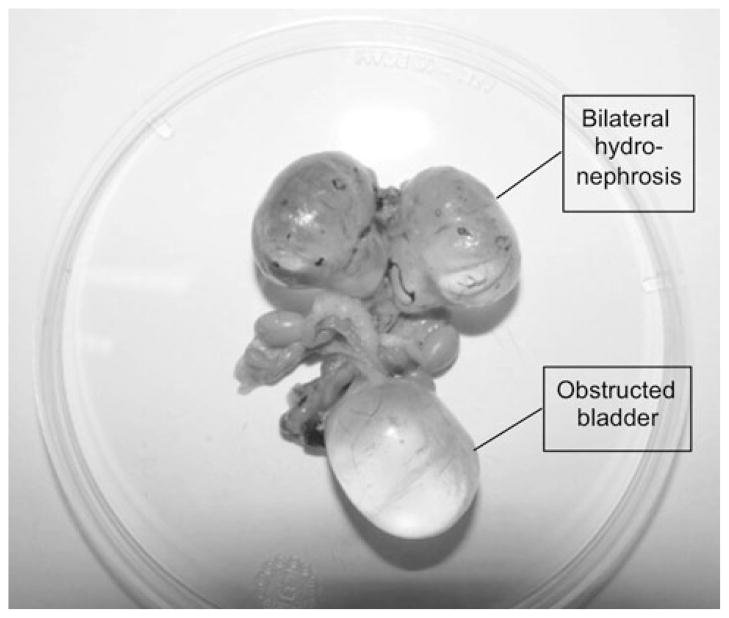

Since the homozygous absence of CK2α alleles lead to severe defects in embryonic heart development, we assessed heart function in CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− adult mice by echography. The total mass of the heart and left ventricular mass were less in the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice compared to other genotypes, but when corrected for body weight there was no difference. No differences in heart rate or fractional shortening were found. Longevity was not different comparing CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice to mice of other genotypes. However, in these experiments, ~40% of mice of any of the CK2-deficient genotypes that became sick proved to have bladder obstruction and hydronephrosis on necropsy (Fig. 3), a phenotype rarely seen in control mice.

Fig. 3.

Hydronephrosis and bladder dilatation in a CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/− male mouse at 17 months of age. This is representative of the obstructive phenotype occurring in CK2 catalytic subunit-deficient mice, with an onset as early as 6 months of age

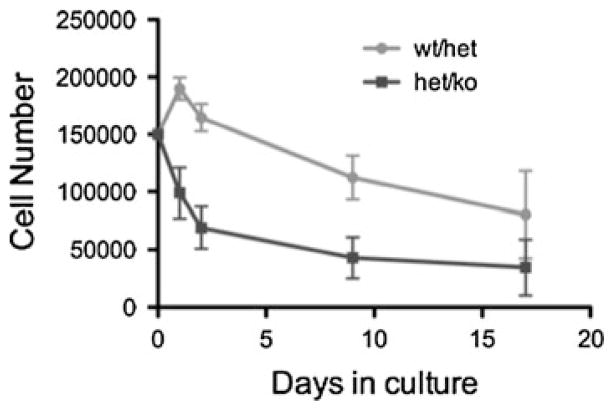

Reduced weight of the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice could be a consequence of a metabolic abnormality, or due to a reduction in cell size or number in organs and tissues, or both. To determine whether cell division is abnormal in CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− cells, we established mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) lines from CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/−embryos, and used CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/− as controls. In preliminary experiments, we found a reduced doubling time of CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− MEFs, compared to CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/− MEFs (Fig. 4). Cell cycle studies identified a delay in exit from G2, with no difference in apoptosis or senescence (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Doubling of MEFs. First passage “Wt/het” (CK2α+/+CK2α′ +/−) MEFs expanded in number for the first few days in culture and then declined, while “het/ko” (CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/−) MEFs failed to expand. N = 5 independent MEF lines of each genotype

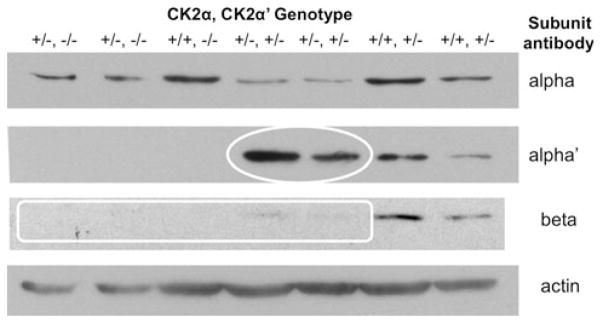

The MEFs were used to assess expression of CK2 catalytic and regulatory subunits. MEFs derived from mice with a single CK2α allele had about 50% of the CK2α protein level (Fig. 5) and mice with a single CK2α′ allele had about about 50% of the CK2α′ protein level. In CK2α+/−CK2α′ +/− double heterozygous mice, we see a relative increase in CK2α′ protein expression, suggesting that there maybe a compensatory increase in CK2α′ with a reduction in CK2α gene dosage (white oval, Fig. 5). Also, we find that CK2β is downregulated in proportion to the loss of catalytic subunits (white rectangle); we and others have shown that CK2β requires the presence of α subunits to retain its stability [15, 16].

Fig. 5.

Expression of CK2 subunits in MEFs of different genotypes. Protein extracts were prepared from first passage MEFs. 40 μg of protein lysate was subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the CK2 catalytic and regulatory subunits, and for actin as a loading control.

Discussion

In this genetic experiment, we demonstrate that mice with combined loss of CK2α and CK2α′ can be viable as long as one CK2α allele is present. However, more than half of embryos with the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− genotype die after mid-gestation. The defects in these embryos could involve CNS or heart development, as seen for embryos in which two alleles of CK2α is missing [13]. Once they get past the developmental hurdle imposed by CK2 deficiency, the CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice are born and live a normal life span without any apparent cardiac defect. However, they have reduced body mass compared to other genotypes throughout life. Abnormal regulation of cell proliferation may explain this, as MEFs derived from embryos of this genotype have reduced doubling time, apparently due to a delay in cell cycle progression rather than an increase in senescence or apoptosis. However, we cannot exclude developmental or metabolic abnormalities also contributing to this phenotype, which seems to predominantly affect body fat.

In these studies, we observed bladder and kidney abnormalities in mice of varying CK2 catalytic subunit-deficient genotypes. In humans, malformation of the vesiculoureteral junction is a frequent developmental abnormality; it is possible that a reduction in CK2 activity is phenocopying this in the mice.

In conclusion, CK2α+/−CK2α′ −/− mice have a phenotype that is not seen in mice lacking one copy of CK2α or two copies of CK2α′. These results suggest that there is an additive effect of the two knockouts. Thus, this provides genetic evidence that the domains of activity of the CK2α and CK2α′ genes are not entirely overlapping, as shown in the last schematic in Table 2. Further studies will be required, using techniques such as gene expression profiling, to determine the unique targets and pathways perturbed with deletion of the two separate gene products. In addition, gene knock-in experiments could distinguish functional versus expression differences in the CK2 catalytic subunits. It is also possible that down regulation of the CK2β subunit, as seen in the MEFs, contributes to the combined knockout phenotype, as CK2β plays a role in the specificity of substrate recognition and in binding of protein partners [17, 18].

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NCI R01 CA71796 (DCS). The authors acknowledge the assistance of Patrick Hogan with animal husbandry, Drs. Ravi Jasuja and GianlucaToraldo in the Metabolic Phenotyping Core for assistance with the NMR analysis, members of the Seldin laboratory, and Dr. Isabel Dominguez for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Salvi M, Sarno S, Cesaro L, Nakamura H, Pinna LA. Extraordinary pleiotropy of protein kinase CK2 revealed by weblogo phosphoproteome analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.013. S0167-4889(09)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meggio F, Pinna LA. One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? FASEB J. 2003;17:349–368. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0473rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanif IM, Shazib MA, Ahmad KA, Pervaiz S. Casein kinase II: an attractive target for anti-cancer drug design. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1602–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.010. S1357-2725(10)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landesman-Bollag E, Romieu-Mourez R, Song DH, Sonenshein GE, Cardiff RD, Seldin DC. Protein kinase CK2 in mammary gland tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:3247–3257. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seldin DC, Leder P. Casein kinase II alpha transgene-induced murine lymphoma: relation to theileriosis in cattle. Science. 1995;267:894–897. doi: 10.1126/science.7846532. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra B, Issinger OG. Protein kinase CK2 in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1870–1886. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trembley JH, Chen Z, Unger G, Slaton J, Kren BT, Van Waes C, Ahmed K. Emergence of protein kinase CK2 as a key target in cancer therapy. Biofactors. 2010;36:187–195. doi: 10.1002/biof.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarno S, Pinna LA. Protein kinase CK2 as a druggable target. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:889–894. doi: 10.1039/b805534c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddiqui-Jain A, Drygin D, Streiner N, Chua P, Pierre F, O’Brien SE, Bliesath J, Omori M, Huser N, Ho C, Proffitt C, Schwaebe MK, Ryckman DM, Rice WG, Anderes K. CX-4945, an orally bioavailable selective inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, inhibits prosurvival and angiogenic signaling and exhibits anti-tumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10288–10298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J. 2003;369:1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan JS, Litchfield DW. Too much of a good thing: the role of protein kinase CK2 in tumorigenesis and prospects for therapeutic inhibition of CK2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenbach L, Fauss J, Robitzki A, Krehan A, Lorenz P, Lozeman FJ, Pyerin W. Recombinant human casein kinase II. A study with the complete set of subunits (alpha, alpha′ and beta), site-directed autophosphorylation mutants and a bicistronically expressed holoenzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou DY, Dominguez I, Toselli P, Landesman-Bollag E, O’Brien C, Seldin DC. The alpha catalytic subunit of protein kinase CK2 is required for mouse embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:131–139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Toselli PA, Russell LD, Seldin DC. Globozoo-spermia in mice lacking the casein kinase II alpha′ catalytic subunit. Nat Genet. 1999;23:118–121. doi: 10.1038/12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seldin DC, Lou DY, Toselli P, Landesman-Bollag E, Dominguez I. Gene targeting of CK2 catalytic subunits. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;316:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C, Vilk G, Canton DA, Litchfield DW. Phosphorylation regulates the stability of the regulatory CK2beta subunit. Oncogene. 2002;21:3754–3764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolanos-Garcia VM, Fernandez-Recio J, Allende JE, Blundell TL. Identifying interaction motifs in CK2beta—a ubiquitous kinase regulatory subunit. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poletto G, Vilardell J, Marin O, Pagano MA, Cozza G, Sarno S, Falques A, Itarte E, Pinna LA, Meggio F. The regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 contributes to the recognition of the substrate consensus sequence. A study with an eIF2 beta-derived peptide. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8317–8325. doi: 10.1021/bi800216d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]