Abstract

The purpose of this research was to develop a sensitive and reproducible UPLC-MS/MS method to simultaneously quantify genistein, genistein-7-O-glucuronide (G-7-G), genistein-4’-O-glucuronide (G-4’-G), genistein-4’-O-sulfate (G-4’-S) and genistein-7-Osulfate (G-7-S) in mouse blood samples. After the method was fully validated over a wide linear range, it was applied to quantify the levels of genistein and its metabolites in a mouse bioavailability study. The linear response range were 19.5–10,000 nM for genistein, 12.5–3,200 nM for G-7-G, 20–1280 nM for G-4’-G, 1.95–2,000 nM for G-4’-S, and 1.56–3,200 nM for G-7-S, respectively. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 4.88, 6.25, 5, 0.98 and 0.78 nM for genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, respectively. Only 20 µl mouse blood sample from i.v. and p.o. administration were needed for analysis because of the high sensitivity of the method. The intra- and inter-day variance is less than 15% and accuracy is within 85–115%. The analysis was finished within 4.5 min. The applicability of this assay was demonstrated and successfully applied for bioavailability study in FVB mouse after i.v. and p.o. administration of 20 mg/kg of genistein, and its oral bioavailability was ~24%.

Keywords: Genistein, phase II metabolites, pharmacokinetics, UPLC-MS/MS

1. Introduction

Genistein, a predominant dietary isoflavone present in legumes such as soy, has been shown in many epidemiological studies and animal experiments to have significant biological activities in various aging-related and hormone-dependent disorders, ranging from cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, to post menopause symptoms [1–6]. The major concern for genistein as a chemopreventive agent is that it is mainly present as its metabolites (i.e. glucuronides and sulfates) after oral administration [7–9], because of extensive first-pass metabolism (by UGTs and SULTs) in intestine and liver [10,11] Pharmacokinetic studies show that genistein has less than 15% absolute bioavailability (BA) in rodents and humans when administered orally [7–12]. The in vivo plasma concentration of genistein is significantly less than the IC50 value for its anticancer and other beneficial effects in vitro [13–14]. But Zhang et al found genistein glucuronides activated human natural killer cells at nutritionally relevant concentrations which showed genistein conjugates might also be active components [15].

Analytical methods for genistein quantification have been developed using enzyme linked immnuosorbent assay (ELISA) [16], fluorescence immunoassay (FIA) [17], and HPLC with MS, UV or electrochemical detector [18–20]. But only a few of published papers describe the analysis of genistein and its conjugates in plasma after its oral administration in rats and humans [8,9,21,22]. Doerge et al. determined two genistein glucuronides’ (G-7-G, G- 4’-G) concentrations in human blood sample with LC/MS after selective enzymatic hydrolysis, but no sulfates’ profiles were published [8]. Soucy et al. and Moon et al. analyzed genistein and its total glucuronides and sulfates in rats with LC-MS/MS, but not for individual metabolites [21,22]. Hosoda et al. used HPLC to detect genistein and its four conjugates in human plasma (G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S) [9], but they used 1 ml human plasma sample. In any rate, currently, there is no study that has simultaneously determined genistein and its four main conjugates using both intravenous and oral administration in an oral bioavailability study. Therefore, we have performed a pharmacokinetic study using both oral and intravenous administration routes in mice. Mice were chosen for two reasons. First, most efficacy studies in animal models employed mice and second, many genetically modified mice strain, such as BCRP knockout mice, are available to investigate the mechanism of disposition of genistein and its metabolites. However, a sensitive and reproducible LC-MS/MS method is needed for the proposed study since blood volume of a mouse is very small, and sequential samples from a single mouse are desirable since genetically modified mice are hard to find and very costly.

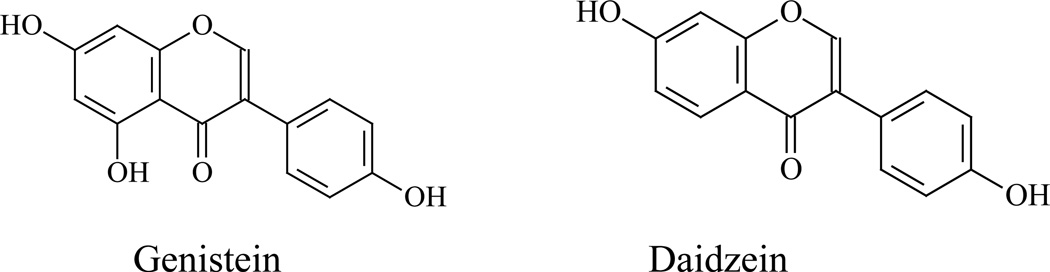

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to develop a more sensitive, reliable and robust UPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determine genistein and its four conjugates (G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S) using a small volume of mouse blood. This method had been validated and applied to genistein pharmacokinetic study in FVB mouse after i.v. and oral administration. There are four genistein conjugates which have been identified from the in vivo studies and their structures are provided (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

The structures of genistein, daidzein (I.S.), G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Genistein and daidzein were purchased from LC laboratory (Woburn, MA). Uridine-5’-diphosphate-β,D-glucoonic acid ester (UDPGA), 3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulfate (PAPS), â-glucuronidase, sulfatase (without â-glucuronidase), D-saccharic-1,4-lactone monohydrate, magnesium chloride, 2,6-lutidine, tert-butyldimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate,7-tert-butyldimethlsilylgenistein, chlorosulfonic acid, tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF), and Hanks’ balanced salt solution (powder form) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Expressed human UGT isoforms UGT1A1, 1A9, 1A10, SULT1A1 and 1E1 were purchased from BD Biosciences (Woburn, MA). Solid phase extraction (C18) columns were purchased from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ). Oral suspension vehicle was obtained from Professional Compounding Centers of America (Houston, TX). Non-soy rat chow (AIN 76A) was purchased from Harlan laboratory (Madison, WI). All other materials (typically analytical grade or better) were used as received.

2.1.1 Chemical Synthesis of Genistein-4’-sulfate (G-4’-S)

Genistein-4’-O-sulfate was chemically synthesized using a method similar to the one published by Fairley et. al [23]. The final product was purified by Sephadex LH-20 column using methanol as the elute solvent (12.4 mg, 0.035 mmol, 17.7 % yield). The genistein sulfate molecular ion (349) and fragments peaks (80, 269) [24] were shown as expected in MS spectra (MS chromatogram not shown) and the aromatic protons adjacent to the sulfate groups at the 3'/5' and 2'/6' positions were shifted downfield from δ 6.82 (2H, dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz) to δ 7.17 (2H, dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz) ppm and from δ 7.37 (2H, dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz) to δ 7.41 (2H, dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz) ppm as expected in 1H NMR experiment (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz)[25].

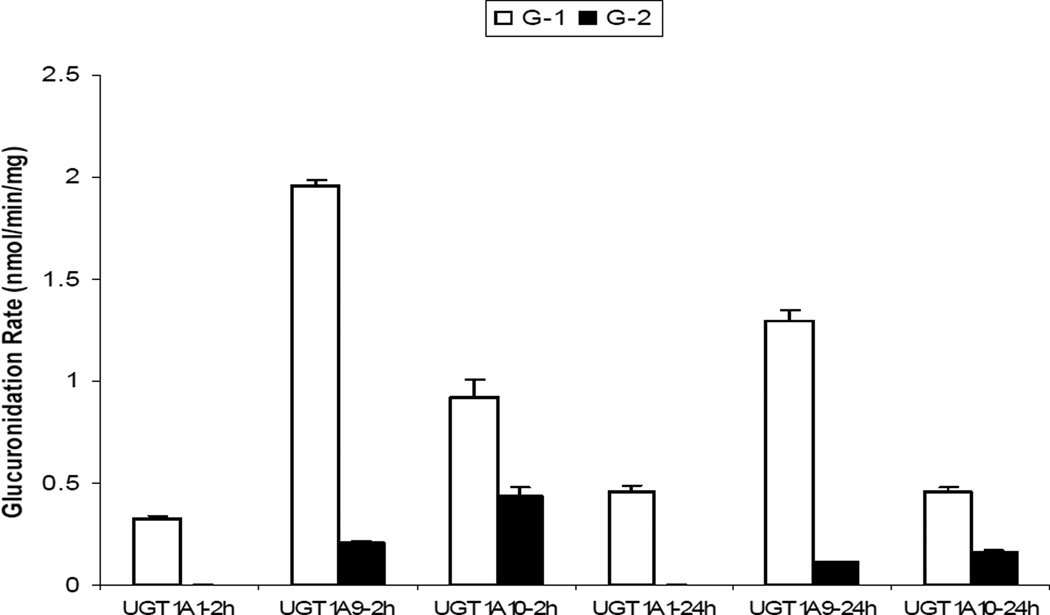

2.1.2 Biosynthesis of G-7-G

G-7-G was biosynthesized using expressed human UGTs, as reported earlier [8]. In that study, after genistein was incubated with UGT1A1 for 2 h, G-7-G was the major metabolite and the ratio of G-7-G/G-4’-G was >100 (data shown in results parts). Here, the same approach was used, although the UGT reaction procedures employed were the same as those described in many of our previous paper [26–29].

2.1.3 Biosynthesis of G-7-G and G-4’-G

G-7-G and G-4’-G were biosynthesized by using UGT 1A10, which was shown to produce similar amounts of both glucuronides [8]. All other experiment procedures were the same as those described using UGT 1A1 (described above).

2.1.4 Biosynthesis of standards of G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S

We obtained the standard of G-4’-S by chemical synthesis. For the rest of genistein phase ΙΙ metabolites, we used FVB mouse intestine to biosynthesize standards of G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, which was achieved via intestinal perfusion [30]. The advantage of biosynthesis is that a large amount of metabolites could be accumulated for method development and validation purposes. The intestinal surgical procedures were described in many of our previous publications [10, 30–32]. Mouse intestinal perfusion samples obtained after 20 µM of genistein perfused at the flow rate of 0.191 ml/min were used to concentrate genistein metabolites. Each 9 ml of mouse intestinal perfusion samples was applied to a C18 solid phase extraction column. After washing out the salt, 1 ml of methanol was then used to elute genistein and its four conjugates. The eluted fractions of methanol were collected and dried under nitrogen, and the residue was reconstituted in 100 µl of acetonitrile to concentrate metabolites. The stock solutions of genistein and its four metabolites were stored in acetonitrile at −80°C until analysis.

2.2. Instruments and conditions

2.2.1 UPLC

A UPLC system, Waters Acquity™ with diode-arrayed detector (DAD) was performed to determine the standards of genistein glucuronides and sulfates. The UPLC conditions for analyzing genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S and daidzein (I.S.) in aqueous samples were: column, Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (50 ×2.1 mm I.D., 1.7 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA); mobile phase A, 100% aqueous buffer (2.5mM ammonium acetate, pH7.4) ; mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile; gradient, initial, 5% B, 0–0.5 min, 5–19% B, 0.5–2 min, 19% B, 2–2.5 min, 19–40% B, 2.5–3.1 min, 40–52% B, 3.1–3.5 min, 52–80% B, 3.5–4 min, 80-5%, 4–4.5 min, 5% B; flow rate, 0.45 ml/min; column temperature, 45°C; sample temperature, 20°C; and injection volume, 10 µl.

2.2.2 LC-MS/MS

For LC-MS/MS analysis, an API 3200-Qtrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystem/MDS SCIEX, Foster City, CA) equipped with a TurboIonSpray™ source was operated at the negative ion mode. The concentrations of G, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S and D (I.S.) in blood sample were determined by MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) method in the negative ion mode. The main working parameters for mass spectrum were set as follows: ionspray voltage, −4.5 kV; ion source temperature, 700°C; gas1, 60 psi; gas2, 60 psi; curtain gas, 10 psi, collision gas, high. The quantification was performed using MRM method with the transitions of m/z 269 → m/z 133 for G, m/z 253 → m/z 132 for D (IS), m/z 455 → m/z 269 for G-7-G and G-4’-G, and m/z 349 → m/z 269 for G-4’-S and G-7-S. Additional compound-dependent parameters in MRM mode for genistein, its four metabolites and daidzein were summarized in Table 1. Analyte concentrations were determined using the software Analyst 1.4.2.

Table 1.

Compound-dependent parameters for genistein, its four metabolites and daidzein (I.S.) in MRM mode for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. Monitored ion pairs were shown in Fig.6.

| Analyte | Dwell time |

DP | CEP | CE | CXP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | V | V | V | V | |

| Genistein | 100 | −80 | −22 | −40 | −2 |

| G-7-G | 100 | −30 | −34 | −40 | −3 |

| G-4’-G | 100 | −30 | −34 | −40 | −3 |

| G-4’-S | 100 | −22 | −21 | −36 | −3 |

| G-7-S | 100 | −22 | −21 | −36 | −3 |

| Daidzein | 100 | −75 | −30 | −52 | −2 |

DP: Declustering Potential; CEP: Collision cell entrance potential; CE: Collision Energy; CXP: Collision cell exit potential

2.3. Determination of concentrations of genistein conjugates

Because individual standards of genistein metabolites were difficult to purify, we determined the concentration of four metabolites using a genistein standard curve and conversion factors of extinction coefficients (EC) for each of the metabolites. Doerge et, al. used the same approach to quantify genistein metabolites [8], and they claimed that extinction coefficients of genistein metabolites were identical with genistein for their analytical conditions. From this study, the values of extinction coefficients were slightly variable with a different liquid chromatography condition (e.g., different pH value and elution gradient). Hence, the conversion factors of EC values of each of the four genistein metabolites were determined using a UPLC condition.

2.3.1 Determinations of conversion factors

Determination of conversion factors (K) has been described previously [10,26]. Briefly, it was determined by comparing (a) the peak area change in aglycon after glucuronides and/or sulfates were hydrolyzed by β-glucuronidases/sulfatase with (b) the corresponding peak area change in glucuronides/sulfates. By plugging various K values into the following equations using peak areas of metabolite, concentrations of metabolites (CG1, CG2, CS1, CS2) were calculated by equation (1)–(4)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where were the concentrations of genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, respectively, and K, KG2, KS1 and KS2 were conversion factors of G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, respectively.

2.4. Bioavailability study in vivo

2.4.1 Animals

Male FVB mice (22–27g, 8–10 weeks old) were from Harlan Laboratory (Indianapolis, IN) and kept in an environmentally controlled room (temperature: 25 ±2°C, humidity: 50±5%, 12 h dark-light cycle) for at least 1 week before the experiments. The mice were fed with non-soy food (AIN 76A) for at least one week before the experiments and were fasted overnight before the date of the experiment. This enabled daidzein to be used as the internal standard.

2.4.2 Experimental design

The animal protocols used in this study were approved by the University of Houston’s Institutional Animal Care and Uses Committee. Mice were fasted for 12 h with free access to water prior to the pharmacokinetic study. Two groups of mice were treated as following: i.v. injection of 10 mM genistein solution [prepared in a solution of 100 mM sodium bicarbonate: PEG 300 (7:3) (pH 9.5)] was administrated through lateral tail vein at dose of 20 mg/kg. Genistein was evenly dispersed in oral suspension vehicle and then given orally to mice at the same dose (20 mg/kg). After the mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane gas, its tail was snipped near the tip of the tail to allow the collection of blood samples. Blood samples (20–25 µl) were collected in heparinized tubes at 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, 480, and 1440 min after an i.v. administration, or 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240, 360, 480, and 1440 min after an oral administration, respectively. The blood samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

2.4.3 Blood sample preparation

The blood sample (20 µl) was spiked with 100 µl of I.S. (daidzein in acetonitrile, 3µM). The mixture was vortexed for 1 min. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant were transferred to a new tube and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 100 µl of 15% acetonitrile aqueous solution and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. 10 µl of supernatant were injected into the UPLC-MS/MS system for quantitative analysis.

2.4.4 Preparation of standard and quality control samples

Five stock solutions, each containing either 80 µM of G, 64 µM G-7-G, 3.2 µM of G-4’-G, 8 µM of G-4’-S or 16 µM of G-7-S was prepared in acetonitrile. An additional stock solution of 3 µM daidzein (I.S.) was also prepared in acetonitrile. Calibration standard samples for genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S were prepared by spiking the blank mouse blood with above stock solutions to arrive at the following analyte concentrations: 9.75, 19.5, 39, 78, 156, 625, 1,250, 2,500, 5,000, 10,000 nM for genistein; 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1,600, 3,200 nM for G-7-G; 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1,280 nM for G-4’-G; 1.95, 3.9, 7.8, 15.6, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1,000 nM for G-4’-S; 0.78, 1.56, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1,600 nM for G-7-S. The quality control (QC) samples for each compound were prepared at three different concentrations in the same way as the blood samples for calibration, and QC samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

2.4.5 Method validation

2.4.5.1 Calibration curve and LLOQ

Calibration curves were prepared according to the method described in section 2.4.3. The linearity of each calibration curve was determined by plotting the peak area ratio of genistein/its metabolites to I.S. in the mouse blood. A least-squares linear regression method (1/x2 weighting) was used to determine the slope, intercept and correlation coefficient of linear regression equation. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was determined based on the signal-to-noise ratio of at least 10:1.

2.4.5.2 Precision and accuracy

The “Intra-day” and “Inter-day” precision and accuracy of the method were determined with three different concentrations QC samples on the same day or on three different days.

2.4.5.3 Extraction recovery and matrix effect

The extraction recoveries of genistein and its four metabolites were determined by comparing (a) the peak areas obtained from blank plasma spiked with analytes before the extraction with (b) those from samples to which analytes were added after the extraction. Matrix effect was assayed to compare (a) the peak areas of blank plasma extracts spikes with analytes with (b) those of the standard solutions dried and reconstituted with a mobile phase.

2.4.5.4 Stability

Short-term (25°C for 4 h), post-processing (20°C for 8 h), long-term (−20°C for 7 days) and three freeze-thaw cycle stabilities were determined.

2.4.6 Data analysis

WinNonlin 3.3 was used for the pharmacokinetic analysis of genistein and its four metabolites. The non-compartmental approach was applied for analysis of the data following i.v. and oral administration of genistein.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The data in this paper were presented as mean±SD, if not specified otherwise. Significance differences were assessed by using unpaired Student’s t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 or p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Conversion factors of genistein metabolites

We performed the hydrolysis experiments at three different concentrations to calculate average K values. The conversion factors K were used to calculate the concentration of standards of G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S using the standard curve of genistein.

The following is a list of the conversion factors used: KG1=1.09, KG2=0.97, KS1=1.01, KS2=1.01 These conversion factors were essentially the same as those reported previously for the genistein glucuronides [26].

3.2 Chromatography and mass spectrometry

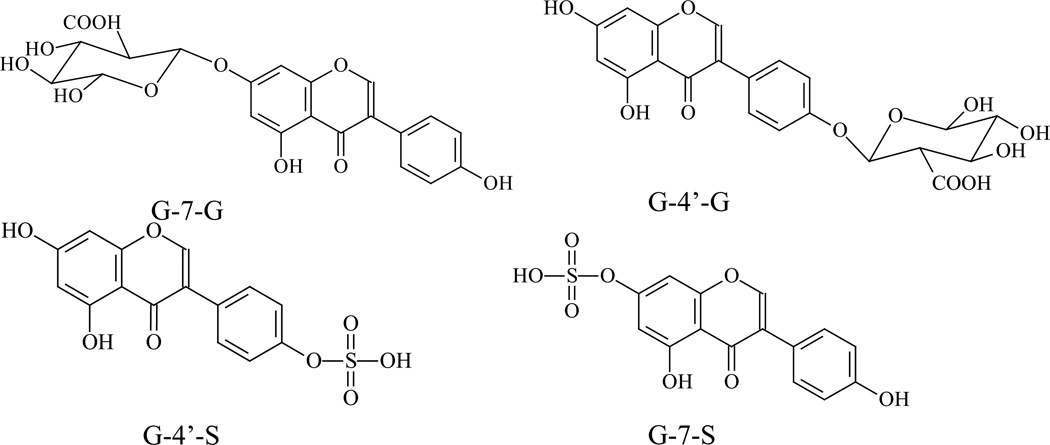

A specific, sensitive and reliable method to determine genistein and its four metabolites’ concentrations had been established. This is the first LC-MS/MS method that directly determines individual conjugates of genistein without enzymatic hydrolysis. Typical chromatograms of spiked genistein and its four metabolites’ in blank mouse blood sample were shown in Fig.2. The retention time of G1, G2, S1, S2, daidzein (I.S.) and genistein were 1.19, 1.44, 1.89, 2.04, 2.25 and 2.64 min, respectively. The position of glucuronide/sulfates was confirmed (see later) using the standards generated independently, and G1 was found to be G-7-G, G2 to be G-4’-G, S1 to be G-4’-S, and S2 to be G-7-S.

Figure 2.

The chromatograms of genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S and daidzein (I.S) in mouse blood sample. The identities of the metabolites were demonstrated in the results section later.

3.2.1 Identification of G-7-G and G-4’-G

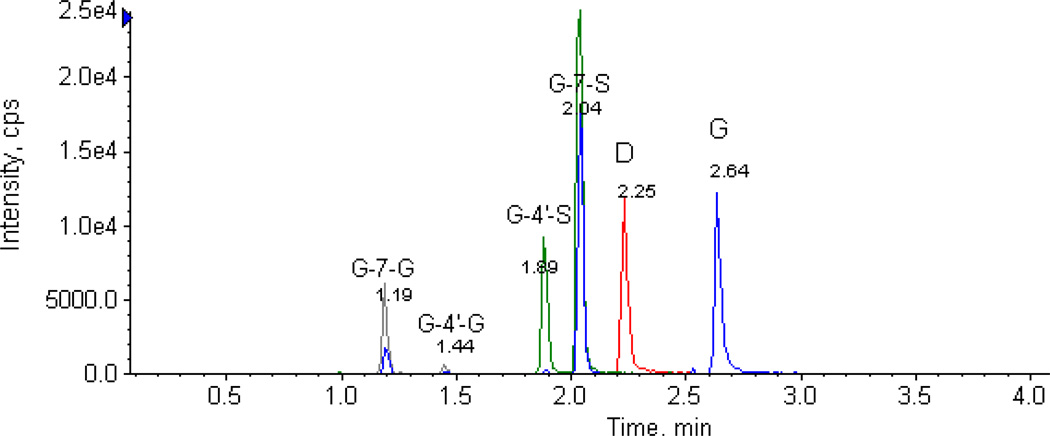

Hosoda et al. have shown that two genistein glucuronides, G-7-G and G-4’-G were present in human plasma samples after oral administration of kinako (baked soybean powder), and G-7-G was eluted faster than G-4’-G in a reversed phase HPLC system (retention time was about 6 min for G-7-G and 7 min for G-4’-G, respectively) [9]. Doerge et al. has shown that genistein can generate two single-glucuronides (G-7-G and G-4’-G) when using recombinant human UGT isoforms 1A1, 1A9 and 1A10. They also found that G-7-G was eluted faster than G-4’-G in a reversed phase HPLC system (retention time was about 11.6 min for G-7-G and 13 min for G-4’-G, respectively). Moreover, they found after 2 h incubation that G-7-G was the predominant glucuronide in glucuronidation reaction catalyzed by expressed human UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10 with the formation ratios (G-7-G/G-4’-G) of 11.2, 11.1 and 2.5, respectively [8].

In the present study, we found that two glucuronides (G-1 and G-2) are present in mouse blood and perfusate samples. The retention time for G-1 was 1.19 min and for G-2 1.44 min. To identify these two glucuronides, we performed a study similar to Doerge et al. by using recombinant human UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10 to measure the formation rates of genistein glucuronides. We found that after 2 h incubation period, the formation ratios (G-1/G-2) were 136, 9.6 and 2.1 for UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10, respectively. Similarly, after 24 h incubation, the formation ratios (G-1/G-2) were 142, 11.6 and 2.9 for UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10, respectively (Fig.3). These results along with previous findings from the other laboratory [8] confirmed that G-1 is G-7-G, whereas G-2 is G-4’-G.

Figure 3.

Genistein glucuronidation in recombinant human UGT isoforms. The open bars represent the formation rates of genistein glucuronide-1 (G-1) in UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10 after incubation times of 2 h and 24 h, respectively. The black bars represent the formation rates of genistein glucuronide-2 (G-2) in UGT1A1, 1A9 and 1A10 after incubation times of 2 h and 24 h, respectively. It was determined that G-1 was G-7-G and G2 was G-4’-G as described in the “results” section. Each bar represents the average of three determinations and the error bar is the standard deviation of the mean.

3.2.2 Identification of G-7-S and G-4’-S

Hosoda et al. have also shown that two genistein sulfates, G-4’-S and G-7-S were present in human plasma samples after oral administration of kinako [9]. In addition, G-4’-S was eluted faster than G-7-S in a reversed phase HPLC system (retention time was about 11 min for G-4’-S and 11.5 min for G-7-S, respectively) [9]. An earlier study by Nakano et al. has shown that genistein generated two single-sulfates (G-7-S and G-4’-S) when using recombinant human SULT1A1 and SULT1E1. Furthermore, after 10 min incubation, they found that G-7-S was the predominant sulfate at 2 µM substrate concentration in the presence of SULT1A1 and the amount of G-7-S formed was 12 times higher than that of G-4’-S. However, in the presence of SULT1E1, and at the same (2 µM) substrate concentration, amounts of G-7-S and G-4’-S formed were comparable [25].

In the present study, we also found that two sulfates were present in mouse blood and perfusate samples. The retention time for S-1 was 1.89 min and S-2 was 2.04 min. To identify these two sulfates, we performed a study similar to Nakano et al. by using recombinant human SULT1A1 and SULT1E1 (in the presence of PAPS) to measure the formation rates of genistein sulfates. We found that after 4 h incubation, the formation ratios (S-1/S-2) were 13.2 and 1.3 for SULT1A1 and SULT1E1, respectively. After 24 h incubation, the formation ratios (S-1/S-2) were 8.7 and 0.22 for SULT1A1 and SULT1E1, respectively (Fig.4). The results along with the previous findings from the other lab25 indicated that S-1 was G-4’-S, whereas S-2 was G-7-S. Additional confirmation was proved by comparing both MS chromatograms and retention time of biosynthesized G-4’-S with chemical synthesized G-4’-S (chromatograms not shown).

Figure 4.

Genistein sulfation in recombinant human SULT isoforms. The open bars represent the formation rates of genistein sulfate-1 (S-1) in SULT1A1 and 1E1 after incubation times of 4 h and 24 h, respectively. The black bars represent the formation rates of genistein sulfate-2 (S-2) in SULT1A1 and 1E1 after incubation times of 4 h and 24 h, respectively. It was determined that S-1 was G-4’-S and S-2 was G-7-S, as described in the “Results” section. Each bar represents the average of three determinations and the error bar is the standard deviation of the mean.

3.2.3 UV absorbance chromatograms of four genistein metabolites

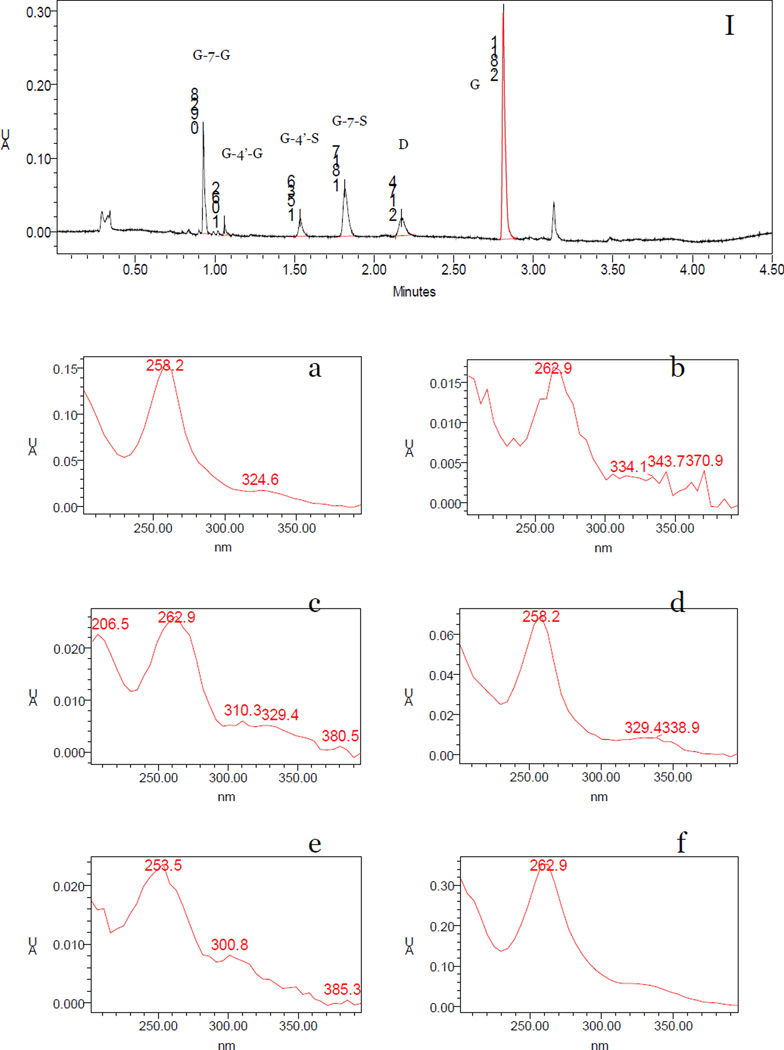

Four metabolite peaks that have UV absorbance profile similar to parent genistein were detected in multiple mouse perfusate and blood samples by DAD analysis (Fig 5a, b, c, d). The retention times of G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S, daidzein (I.S.) and genistein were 0.928, 1.062, 1.536, 1.817, 2.174 and 2.811 min, respectively (Fig 5I). The UV absorbance band of G-4’-S in mouse perfusate and blood sample was exactly the same with chemically synthesized G-4’-S (spectra not shown). G-7-G (Fig 5a) and G-7-S (Fig 5d) had a maximum UV absorbance wavelength (λmax) at 258 nm, which were “blue” shifted when compared to genistein’s λmax (263 nm, Fig 3f). G-4’-G (Fig 5b) and G-4’-S (Fig 5c), on the other hand, had an unchanged λmax at 263 nm. The UV absorbance bands of four metabolites were consistent with the previous studies that showed G1 was G-7-G and S1 was G-4’-S.

Figure 5.

UPLC chromatograms and UV spectra for genistein, its four phase II metabolites and daidzein (I.S). Panel I shows the UPLC chromatograms of genistein and its metabolites at the wavelength of 254 nm, using a concentrated mouse intestinal perfusion samples. Panels show the UV spectra of G-7-G (a), G-4’-G (b), G-4’-S (c), G-7-S (d), daidzein (I.S., e) and genistein (f), respectively. The retention times of each analyte determined by a DAD detector are slightly different with them in mass spectrometry chromatogram due to the minor differences in two mobile phases’ elution schemes in LC versus LC-MS/MS. The latter was necessary to maximize MS/MS signal.

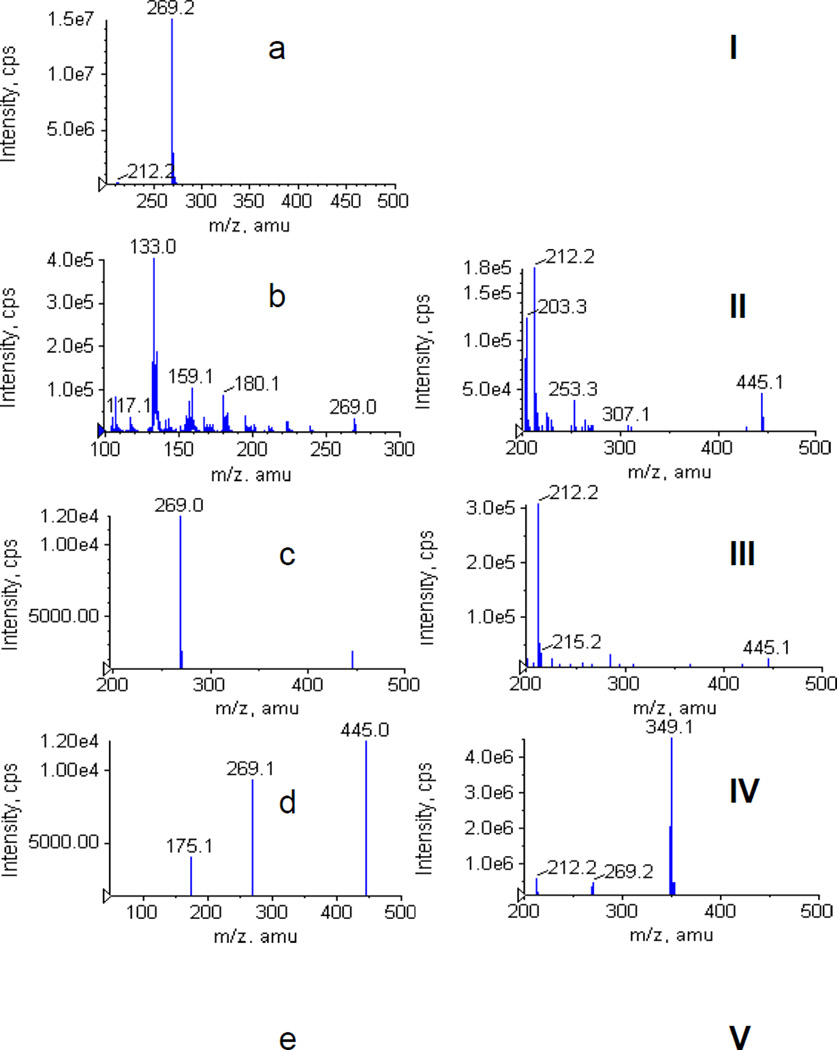

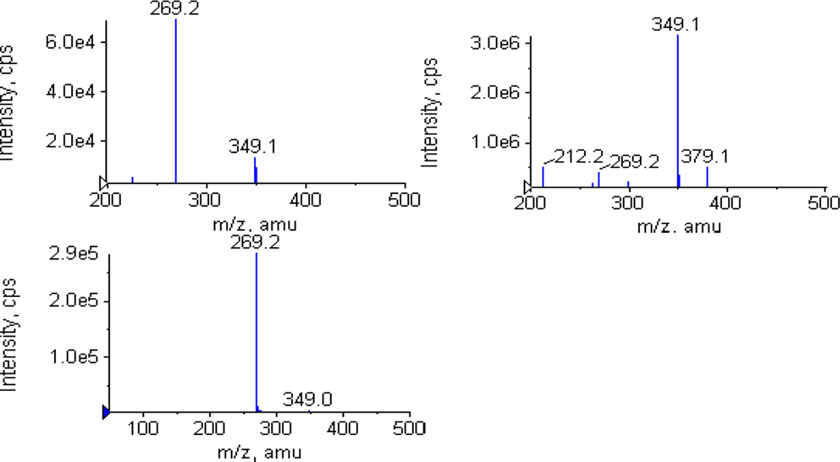

3.2.4 Mass spectrometer chromatograms of four genistein metabolites

Genistein and its metabolites were then confirmed by mass spectrometer. The single-stage full scan mass chromatograms were showed in Figure 6a–e. The MS2 full scan mass chromatograms of genistein and its metabolites were showed in Fig. 6I–V. G-7-G and G-4’-G have the ion [M-H]− at m/z 445 (Fig 6b, c), which was 176 Dalton higher (characteristic of the addition of one glucuronic acid) than that of genistein (m/z 269, Fig 6a). G-4’-S and G-7-S have the ion m/z 349 (Fig 6d, e), which was 80 Dalton higher (characteristic of the addition of one sulfuric acid) than that of genistein (m/z 269). The MS2 full scan also showed that the ion [M-H]− at m/z 445 and 349 can produce fragment ion m/z 269 at collision energy 40v (Fig 6II, III, IV, V), which confirmed existence of genistein glucuronide and sulfate.

Figure 6.

MS chromatograms for genistein and its phase II metablites. Left panels show the MS full scan spectra of genistein(a), G-7-G (b), G-4’-G (c), G-4’-S (d) and G-7-S (e), respectively. Right panels show the MS2 full scan for genistein (I), G-7-G (II), G-4’-G (III), G-4’-S (IV) and G-7-S (V), respectively.

3.3 Specificity, linearity and sensitivity

The method validation was conducted in blank mouse blood. The standard curves were linear in the concentration range of 19.5–10,000 nM for genistein, 12.5–3,200 nM for G-7-G, 20–1,280 nM for G-4’-G, 1.95–1,000 nM for G-4’-S and 1.56–1,600 nM for G-7-S. The linear range of all analytes were much wider than the published method by Hosoda et al [9], which were 212.3–1751.3 nM for genistein, 74.3–885.6 nM for G-7-G, 81.8–1140.6 nM for G-4’-G, 67.0–502.5 nM for G-4’-S, 44.7–586.8 nM for G-7-S. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 4.88, 6.25, 5, 0.98 and 0.78 nM for genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, respectively, which were 3–20 folds higher than those published by Doerge et al using LC/MS [8]. The LLOQ of genistein in the present assay is similar to those obtained from ELISA [16] and FIA [17], but much more sensitive than other published assays using HPLC with mass spectrometer, UV or electrochemical detector [18–20].

3.4 Accuracy and precision

Accuracy, intra-day and inter-day precision were determined by measuring six replicates of QC samples at three concentration levels in mouse blood. The precision and accuracy were shown in Table 2. These results demonstrated that the precision and accuracy values were well within the 15% acceptance range.

Table 2.

Extraction recovery, intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy for genistein and its four conjugates in MRM mode of UPLC-MS/MS analysis

| Extraction recovery (n=3) |

Intra-day (n=6) | Inter-day (n=6) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte | Concentration (nM) |

Average±SD (%) |

Accuracy (Bias, %) |

Precision (CV, %) |

Accuracy (Bias, %) |

Precision (CV, %) |

| 78 | 111.1±17.2 | 110.8 | 8.2 | 96.5 | 4.4 | |

| Genistein | 625 | 114.2±4.8 | 104.8 | 3.7 | 95.7 | 5.8 |

| 5000 | 99.6±9.0 | 92.5 | 5.9 | 91.0 | 3.0 | |

| 50 | 101.2±1.7 | 92.4 | 12.5 | 104.4 | 13.5 | |

| G-7-G | 400 | 86.5±6.7 | 110.7 | 10.1 | 100.8 | 12.7 |

| 3200 | 83.4±5.8 | 109.3 | 13.0 | 113.8 | 5.5 | |

| 40 | 106.8±5.4 | 95.0 | 8.1 | 111.2 | 12.5 | |

| G-4’-G | 160 | 96.9±9.3 | 90.3 | 10.4 | 106.9 | 10.4 |

| 640 | 110.4±9.5 | 101.5 | 8.0 | 106.8 | 9.7 | |

| 15.6 | 104.9±10.5 | 94.7 | 10.9 | 98.1 | 9.7 | |

| G-4’-S | 125 | 101.7±1.9 | 98.4 | 10.0 | 106.5 | 10.6 |

| 1000 | 86.2±5.6 | 102.4 | 7.1 | 106.6 | 6.0 | |

| 25 | 97.3±9.1 | 109.5 | 10.5 | 108.6 | 12.8 | |

| G-7-S | 200 | 82.1±5.0 | 114.4 | 10.2 | 88.9 | 12.0 |

| 1600 | 86.5±1.0 | 91.5 | 13.6 | 91.4 | 13.7 | |

3.5 Recovery, matrix effect, stability

The mean extraction recoveries determined using three replicates of QC samples at three concentration levels (the same concentrations as QC sample) in mouse blood were shown in Table 2. Methanol, acetonitrile and acid precipitation (10% formic acid) were tried to extract genistein and its metabolites in blood sample, the result showed it has the highest extraction recovery when acetonitrile were used (data not shown). As for ionization, the peak areas of genistein and its four metabolites after spiking evaporated blood samples at three concentration levels were comparable to similarly prepared aqueous standard solutions (ranged from 85–115%). It suggested that there was no measurable matrix effect that interfered with genistein and its four metabolites’ determination in the mouse blood.

The stability of genistein and its four metabolites in mouse blood were evaluated by analyzing three replicates of quality control samples at three different concentrations after short-term (25°C, 4 h), post processing (20°C, 8h), long-term cold storage (−20°C, 7 days) and within three freeze-thaw cycles (−20 to 25°C). All the samples displayed 85–115% recoveries after various stability tests.

Taken together, the above results showed that a sensitive, reproducible, and robust method for the analysis of genistein and its four metabolites in mouse blood sample had been developed and validated.

3.6 Bioavailability studies

The validated analytical method was employed to study the pharmacokinetic behaviors of genistein in FVB mice. The mean plasma concentration-time curves of genistein and its four metabolites after i.v. and p.o. administration were presented in Fig.7. Genistein and its four metabolites’ pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by the noncompartmental method, using WinNonlin 3.3 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, California). The fitted pharmacokinetic parameters were shown in Table 3. As can be seen in Table 3, after 20mg/kg intravenous bolus injection, genistein reached a maximum concentration (Cmax) of 57.70±21.84 µM and then declined rapidly. After oral administration of the same dose, genistein was readily absorbed and reached Cmax of 0.71±0.22 µM at approxiately 75 min (Table 3). The AUC0–24h of genistein was 25.85 after i.v. administration, and 6.05 after oral administration, implying an oral bioavailability of 23.4%, much higher than those reported in the literature using male rats (7%) at a smaller dose (4 mg/kg) [7]. Although the oral bioavailability is low in mice, genistein has a very long apparent terminal half-life, as concentrations between 8 and 24 h did not vary much (Fig.7I). In fact, genistein was detectable 7 days after the soy-containing diet was replaced by genistein-free AIN76 diet (not shown). On the other hand, after i.v. administration, sulfate concentrations did not change between 8 and 24 h (Fig.7III, IV). Genistein is also metabolized very rapidly after i.v. administration in mice (Fig.7II, III, IV, V), and the Tmax values of conjugated metabolites were very short at 0, 0.1, 0.05 and 0.05 h for G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S, respectively. In contrast, metabolites increased steadily after oral administration, and Tmax was usually reached in about 3 h (e.g., Tmax values of G-7-G, G-4’-S and G-7-S were 2.75, 3 and 3 h, respectively), although Tmax value of G-4’-G was shorter (1.5 h). This rapid formation of glucuronidated metabolite after i.v. administration was unexpected since genistein is known to undergo heavy first-pass metabolism [7,33], and further studies are need to determine the mechanisms responsible for this observed effect.

Figure 7.

Blood concentrations of genistein (I), G-7-G (II), G-4’-G (III), G-4’-S (IV) and G-7-S (V) after i.v. and oral administration of 20 mg/kg genistein in FVB mice. Each point is average of 4 determinations and the bars are standard deviations of the mean. The 5 and 15 min blood samples from i.v. administration were first diluted 10 times before they were analyzed, since high concentrations of analytes at these time points made their MS signal out of their respective linear response ranges.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of genistein and its metabolites after i.v. and p.o. administration of 20 mg/kg in FVB mice (n=5).

| PK Parameters |

Tmax (h) |

Cmax (µM) | AUC 0-t (h*µM) |

half-life (h) |

k (1/h) | V (mg/(µM)/kg) |

CL (mg/(h*µM)/kg) |

MRTinf (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genistein | I.V. | 0 | 25.85±13.8 | 14.2±9.87 | 0.08±0.06 | 16.05±10.47 | 0.87±0.36 | 4.20±2.1 | |

| P.O. | 1.25±0.29 | 0.71±0.22 | 6.05±0.54 | 46.37±30.56 | 0.030±0.03 | 55.6±16.54 | 1.30±1.0 | 68.08±45.42 | |

| G-7-G | I.V. | 0 | 57.93±17.98 | 26.19±4.67 | - | - | - | - | - |

| P.O. | 2.75±2.25 | 0.982±0.944 | 2.79±2.26 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| G-4'-G | I.V. | 0.1±0.14 | 14.26±4.86 | 11.40±2.55 | - | - | - | - | - |

| P.O. | 1.5±1.08 | 0.53±0.38 | 2.55±0.79 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| G-4'-S | I.V. | 0.05±0.11 | 3.97±0.57 | 2.24±0.32 | - | - | - | - | - |

| P.O. | 3±2.16 | 0.25±0.22 | 1.08±0.72 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| G-7-S | I.V. | 0.05±0.11 | 10.74±1.64 | 6.86±1.23 | - | - | - | - | - |

| P.O. | 3±2.16 | 0.65±0.56 | 2.85±1.58 | - | - | - | - | - |

“-” indicated some pharmacokinetic parameters of metabolites cannot be derived from the non-compartment model used to fit the concentration versus time data.

Lastly, the AUC0–24h values of conjugated metabolites of genistein G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, and G-7-S after i.v. administration were 26.19, 11.40, 2.24, and 6.86 h*µM, respectively. These AUC0–24h values were all substantially (2–20 folds) higher than the corresponding AUC0–24h values after oral administration, which were 2.79, 2.55, 1.08, and 2.85 h*µM for G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, and G-7-S, respectively. This result is consistent with the fact that large quantities of metabolites following oral administration were excreted via enterocytes or bile [11,27], although other mechanisms could not be excluded at this time.

4. Conclusion

A sensitive, reliable, and robust UPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of genistein, G-7-G, G-4’-G, G-4’-S, G-7-S in mouse blood was developed, validated and applied for the genistein bioavailability study in FVB mice. The lower limit of quantification of genistein and its four metabolites were well below the lowest concentrations in FVB mice after i.v. and p.o. administration of 20 mg/kg genistein.

The method was successfully applied for mouse bioavailability study by using only 20µl of mouse blood sample. Therefore, each mouse can be used to derive a complete pharmacokinetic profile. This method is also valuable for human clinical study because it should allow even higher sensitivity than reported here since a large blood volume is usually available and thereby may be used to concentrate the analyte before analysis. The method is now used to investigate transporter mechanism of genistein in mouse in which genistein and its metabolites concentrations are analyzed.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by NIH GM070737 to MH at University of Houston. The authors wish to extend appreciation to Dr. Susan Leonard of Applied Biosystems, Inc. for her assistance during the development of the present LC-MS/MS method.

Abbreviations

- UGTs

UDP-glucuronosyl transferases

- SULTs

sulfotransferases

- UDPGA

uridine-5’-diphosphate-β,D-glucuronic acid

- PAPS

3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulfate

- D

daidzein

- G

genistein

- G-7-G

genistein-7-O-glucuronide

- G-4’-G

genistein-4’-O-glucuronide

- G-4’-S

genistein-4’-O-sulfate

- G-7-S

genistein-7-O-sulfate

- DP

Declustering potential

- CEP

Collision cell entrance potential

- CE

Collision energy

- CXP

Collision cell exit potential

- UPLC

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- IS

Internal standard

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sarkar FH, Li Y. The role of isoflavones in cancer chemoprevention. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2714–2724. doi: 10.2741/1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adlercreutz H. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;83:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setchell KD, Brown NM, Desai PB, Zimmer-Nechimias L, Wolfe B, Jakate AS, Creutzinger V, Heubi JE. Bioavailability, disposition and dose-response effects of soy isoflavones when consumed by healthy women at physiologically typical dietary intakes. J. Nutr. 2003;133:1027–1035. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bektic J, Guggenberger R, Eder IE, Pelzer AE, Berger AP, Bartsch G, Klocker H. Molecular effects of the isoflavonoid genistein in prostate cancer. Clin. Prostate Cancer. 2005;4:124–129. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2005.n.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HF, Wang JD, Qu SY. Phytoestrogen genistein decreases contractile response of aortic artery in vitro and arterial blood pressure in vivo. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2004:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang ZL, Sun JY, Wang DN, Xie YH, Wang SW, Zhao WM. Pharmacological studies of the large-scaled purified genistein from Huaijiao (Sophora japonica-Leguminosae) on anti-osteoporosis. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coldham NG, Zhang AQ, Key P, Sauer MJ. Absolute bioavailability of [14C] genistein in the rat; plasma pharmacokinetics of parent compound, genistein glucuronide and total radioactivity. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2002;27:249–258. doi: 10.1007/BF03192335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doerge DR, Chang HC, Churchwell MI, Holder CL. Analysis of soy isoflavone conjugation in vitro and in human blood using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000;28:298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosoda K, Furuta T, Yokokawa A, Ogura K, Hiratsuka A, Ishii K. Plasma profiling of intact isoflavone metabolites by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric identification of flavone glycosides daidzin and genistin in human plasma after administration of kinako. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1485–1495. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Hu M. Absorption and metabolism of flavonoids in the caco-2 cell culture model and a perused rat intestinal model. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:370–377. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: role of intestinal disposition. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;304:1228–1235. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu M. Commentary: bioavailability of flavonoids and polyphenols: call to arms. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:803–806. doi: 10.1021/mp7001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birt DF, Hendrich S, Wang W. Dietary agents in cancer prevention: flavonoids and isoflavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;90:157–177. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busby MG, Jeffcoat AR, Bloedon LT, Koch MA, Black T, Dix KJ, Heizer WD, Thomas BF, Hill JM, Crowell JA, Zeisel SH. Clinical characteristics and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: single-dose administration to healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;75:126–136. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Song TT, Cunnick JE, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Daidzein and genistein glucuronides in vitro are weakly estrogenic and activate human natural killer cells at nutritionally relevant concentrations. J. Nutr. 1999;129:399–405. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pongkitwitoon B, Sakamoto S, Tanaka H, Tsuchihashi R, Kinjo J, Morimoto S, Putalun W. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for total isoflavonoids in Pueraria candollei using anti-puerarin and anti-daidzin polyclonal antibodies. Planta Med. 2009 doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240725. PMID 20033865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talbot DC, Ogborne RM, Dadd T, Adlercreutz H, Barnard G, Bugel S, Kohen F, Marlin S, Piron J, Cassidy A, Powell J. Monoclonal antibody-based time-resolved fluorescence immunoassays for daidzein, genistein, and equol in blood and urine: application to the Isoheart intervention study. Clin. Chem. 2007;53:748–756. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, Wolff MS, Moline J. Analysis of environmental biomarkers in urine using an electrochemical detector. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2005;819:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klejdus B, Mikelova R, Petrlova J, Potesil D, Adam V, Stiborova M, Hodek P, Vacek J, Kizek R, Kuban V. Determination of isoflavones in soy bits by fast column high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with UV-visible diode-array detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;108:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepehr E, Robertson P, Gilani GS, Cooke G, Lau BP. An accurate and reproducible method for the quantitative analysis of isoflavones and their metabolites in rat plasma using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry combined with photodiode array detection. J. AOAC Int. 2006;89:1158–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soucy NV, Parkinson HD, Sochaski MA, Borghoff SJ. Kinetics of genistein and its conjugated metabolites in pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats following single and repeated genistein administration. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;90:230–240. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon YJ, Sagawa K, Frederick K, Zhang S, Morris ME. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the isoflavone biochanin A in rats. AAPS J. 2006;8:E433–E442. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairley B, Botting NP, Cassidy A. The synthesis of daidzein sulfates. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:5407–5410. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coldham NG, Howells LC, Santi A, Montesissa C, Langlais C, King LJ, Macpherson DD, Sauer MJ. Biotransformation of genistein in the rat: elucidation of metabolite structure by product ion mass fragmentology. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999;70:169–184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(99)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano H, Ogura K, Takahashi E, Harada T, Nishiyama T, Muro K, Hiratsuka A, Kadota S, Watabe T. Regioselective monosulfation and disulfation of the phytoestrogens daidzein and genistein by human liver sulfotransferases. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2004;19:216–226. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang L, Singh R, Liu Z, Hu M. Structure and concentration changes affect characterization of UGT isoform-specific metabolism of isoflavones. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:1466–1482. doi: 10.1021/mp8002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Wang S, Jia X, Bajimaya S, Lin H, Tam VH, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via recycling: comparison of intestinal versus hepatic disposition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:1777–1784. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.003673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu M, Chen J, Lin H. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: mechanistic studies of disposition of apigenin in the Caco-2 cell culture model. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;307:314–321. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang SW, Kulkarni KH, Tang L, Wang JR, Yin T, Daidoji T, Yokota H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1As deficiency in Gunn rats is compensated by increases in UGT2Bs activities. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;329:1023–1031. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong EJ, Jia X, Hu M. Disposition of formononetin via enteric recycling: metabolism and excretion in mouse intestinal perfusion and Caco-2 cell models. Mol. Pharm. 2005;2:319–328. doi: 10.1021/mp0498852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu M, Roland K, Ge L, Chen J, Li Y, Tyle P, Roy S. Determination of absorption characteristics of AG337, a novel thymidylate synthase inhibitor, using a perfused rat intestinal model. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87:886–890. doi: 10.1021/js970251e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia X, Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: enzyme-transporter coupling affects metabolism of biochanin A and formononetin and excretion of their phase II conjugates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;310:1103–1113. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King RA, Broadbent JL, Head RJ. Absorption and excretion of the soy isoflavone genistein in rats. J. Nutr. 1996;126:176–182. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]