SUMMARY

We have explored the role of mitochondrial function in aging by genetically and pharmacologically modifying yeast cellular respiration production during the exponential and/or stationary growth phases, and determining how this affects chronological lifespan (CLS). Our results demonstrate that respiration is essential during both growth phases for standard CLS, but that yeast have a large respiratory capacity and only deficiencies below a threshold (~40% of wild-type) significantly curtail CLS. Extension of CLS by caloric restriction also required respiration above a similar threshold during exponential growth, and completely alleviated the need for respiration in stationary phase. Finally, we show that media supplementation with 1% trehalose, a storage carbohydrate, restores wild-type CLS to respiratory null cells. We conclude that mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast CLS and its extension by caloric restriction by increasing stress resistance, an important component of which is the optimal accumulation and mobilization of nutrient stores.

Keywords: Mitochondrial Respiration, Yeast chronological lifespan, Reactive oxygen species, Caloric restriction, Aging

INTRODUCTION

Biological aging can be defined as the progressive decline in the ability of a cell or an organism to resist stress, damage or disease. Eukaryotic biological systems rely on oxidation and aerobic energy production for sustainability, and as a consequence are permanently exposed to the effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated as respiratory byproducts. The free radical/mitochondrial theory of aging (Harman, 1972) proposes that respiratory ROS damage mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and disturbs aerobic energy production, setting up a “vicious cycle”. Here a progressive energetic decline and ROS-induced cumulative oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules is postulated to eventually overwhelm stress resistance and self-repair systems, thus resulting in further functional decline and aging. Although this is a longstanding theory, evidence supporting and contradicting its postulates, gathered from studies on diverse model organisms, continue to accumulate in the literature (Bonawitz and Shadel, 2007; Longo and Fabrizio, 2002; Ristow and Schmeisser, 2011; Trifunovic and Larsson, 2008). Overall, these studies suggest that although oxidative damage is an important contributor, there is more to aging than damage mediated by ROS.

Over the last two decades, Saccharomyces cerevisiae models of aging have contributed the discovery of conserved longevity factors that modulate aging in mammals (Fontana et al., 2010; Kaeberlein, 2010). It has been established that lack of mitochondrial respiration severely affects the ability of yeast cells to achieve a standard wild-type chronological lifespan (CLS) (Aerts et al., 2009; Bonawitz et al., 2006; Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011). CLS is a model for the aging process of post-mitotic cells, defined as the capacity of postdiauxic stationary (G0) cultures to maintain viability over time. Mitochondrial function plays important roles in CLS extension mechanisms (Smith et al., 2007). This is the case of yeast strains with reduced “target of rapamycin” (TOR) nutrient sensor signaling, a longevity pathway conserved from yeast to mammals. TORC1 signaling-deficient strains have a higher density of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes per organelle, increased coupled respiration, and enhanced ROS production during exponential growth that provides an adaptive signal that extends CLS (Bonawitz et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2011).

Caloric restriction (CR) is an intervention that extends the lifespan of a variety of eukaryotic organisms from yeast to mammals. The mechanisms by which CR operates in yeast involves, in part, inhibition of nutrient-responsive kinases such as TOR and RAS2 (Wei et al., 2008), general enhancement of stress-resistance mechanisms, and metabolic remodeling involving the shift from fermentation to respiration (Oliveira et al., 2008).

For CLS studies, yeast cells are usually aged in media containing 2% glucose. Under these conditions, cells rapidly divide producing energy preferentially by fermenting pyruvate to ethanol, which is mostly secreted into the medium, while respiration is repressed in a glucose concentration-dependent manner. As glucose is being consumed, growth slows down and the diauxic shift occurs, involving up-regulation of nuclear genes important for mitochondrial biogenesis and use of ethanol for energy production through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). When cell division stops, yeast in culture rely on their own nutrient storages (such as glycogen and trehalose) for survival. It has recently been proposed that accumulation in the culture medium of toxic acetic acid produced during ethanol metabolism induces an apoptosis-like response involving mitochondrial ROS production that limits yeast CLS (Burtner et al., 2009; Kaeberlein, 2010) and that CR (usually 0.5% glucose) extends CLS by favoring respiratory metabolism and reducing the accumulation of acetic acid (Burtner et al., 2009). However, we have recently shown that, at least in the case of cells with reduced TOR signaling, this is not the case and increased mitochondrial respiration and ROS production are cell-intrinsic factors regulating CLS (Pan et al., 2011). Nonetheless, how changes in mitochondrial respiration and ROS generation interplay to regulate CLS remain largely unexplored.

In this study, we systematically analyzed the role of mitochondrial function in yeast CLS and its extension by CR by modulating respiration and OXPHOS using genetic and pharmacological interventions. In doing so, we have revealed new insights into respiratory thresholds and stress-resistance pathways that control yeast aging.

RESULTS

Multi-factorial contribution of respiratory rate to CLS

Several laboratory strains commonly used in aging research are genetically and physiologically heterogeneous, which is somehow reflected in their CLS (Fabrizio and Longo, 2007; Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011). Many commonly used strains, including BY4741, are S288c derivatives which carry a mutation affecting Hap1, a heme-dependent regulator of a number of genes involved in electron-transfer reactions (Gaisne et al., 1999). This contributes to their reduced ability to respire when compared with strains carrying a wild-type HAP1 gene such as W303 (Figure S1A-B), although other genetic differences between the strains may also contribute. However, like W303, the Hap1-deficient BY4741 strain reduced its metabolic rate when it reached the stationary phase and the respiratory rate of both strains at day 0 (72h after inoculation) was 20% of their exponential phase respiratory rate (Figure S1C). The CLS of these strains correlated with their respiratory rate, with W303 having a maximum CLS of ~11 days and BY4741 a maximum CLS of 8 days (Burtner et al., 2009; Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011). Importantly, this difference in CLS did not correlate with the amount of toxic metabolites, mainly acetic acid, in the culture media, which is lower in the short-lived BY4741 background (Figure S1D).

ROS and oxidative damage are implicated in aging and reductions have been associated with mechanisms of life span extension in yeast and mammals. Furthermore, we recently showed that an adaptive ROS signal during exponential growth contributes to extension of yeast CLS mediated by reduced TORC1 signaling (Pan et al., 2011). Therefore, we ascertained the contribution of ROS to the observed differences in CLS the BY4741 and W303 strains with different respiratory capacities. While BY4741 produces less ROS (DHE staining) than W303 cells during the exponential phase, both strains exhibited similar amounts in stationary phase (Figure S1E). Because W303 cells produce substantially more ROS during exponential growth, we have asked whether a further increase would extend their CLS. Using the same menadione treatment regimen during growth, which we showed previously extends CLS in BY4741 and DBY2006 strains (Pan et al., 2011), we observed only minor extension of CLS in W303 (Figure S1F). This is consistent with the minimal effect of tor1Δ on CLS in W303 (extension of 1.4 fold, (Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011)) compared to DBY2006 (extension of 2.5 fold (Bonawitz et al., 2007)), despite W303 tor1Δ strains having hyperpolarized mitochondria and producing significantly more ROS than wild-type cells during exponential growth (Figure S2A and B) like DBY2006 tor1Δ strains (Pan et al., 2011). We next tested the effect mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) overexpression (OE) could have on W303 CLS. As shown in Figure S1G, SOD2 OE curtailed CLS in W303, in a way similar to the effect of SOD2 OE in DBY2006 tor1Δ strains (Pan et al., 2011). Based on these results, we conclude that strains with endogenous high ROS during exponential growth such as W303 have largely maximized the stress resistance and CLS extension that can be achieved from adaptive ROS signaling and that respiration-dependent factors in addition to ROS contribute to yeast CLS. Therefore, in this study, we chose to use the W303 strain with robust respiratory capacity to better understand how dynamic alterations in respiration contribute to CLS and its extension by CR.

A mitochondrial respiratory threshold regulates CLS

To more quantitatively analyze the role of mitochondrial function during yeast CLS, we have used three groups of W303 respiratory-deficient mutants. The first group included strains unable to respire because they either are devoid of mtDNA (rho0 cells) or carry a null cyc3 allele (cyc3) and thus lack cytochrome c heme lyase and functional cytochrome c (Figure 1A and B). As reported for several respiratory mutants (Aerts et al., 2009; Bonawitz et al., 2007; Bonawitz et al., 2006; Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011), the absence of respiration in rho0 and cyc3 strains severely limits their CLS from a wild-type maximum of 11 days to 3 days (Figure 1C). The second group included shy1 and C199. Shy1 is a cytochrome c oxidase (COX) assembly chaperone and the C199 strain carries a point mutation in Mss51, another COX assembly factor. Both shy1 and C199 strains retain a low level of respiration during the exponential phase, but had no detectable respiration during the stationary phase (Figure 1D and E). The residual ~15% respiration in these strains was not able to support standard wild-type CLS, which was reduced to a maximum of 4 days (Figure 1F). The third group of strains analyzed included cox5a and cyc1 . Cox5 and cytochrome c exist in two isoforms that are differentially regulated by oxygen levels. The normoxic genes are COX5a and CYC1 while the hypoxic genes are COX5b and CYC7. In the absence of the normoxic genes, the hypoxic genes have some leaky expression, which allow for residual respiration. In our growth conditions, during the exponential phase both mutant strains retained 40-50% of wild-type respiration (Figure 1G), while in the stationary phase both mutants respired as much as wild-type strains (Figure 1H). Interestingly, cox5a and cyc1 strains follow a survival curve and have a CLS indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells (Figure 1I). These results indicate that cellular respiration is essential to maintain a standard wild-type yeast CLS. However, there is a large reserve respiratory capacity to sustain CLS, which is significantly affected only when the respiratory rate in exponential phase drops below a threshold near 40-50% that of the wild-type.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast CLS.

(A and B) Cell respiration of W303, rho0 and cyc3 strains during exponential (A) and stationary (B) phases of growth. (C) CLS of W303, rho0 and cyc3 strains. (D and E) Cell respiration of W303, shy1 and C199 strains during exponential (D) and stationary (E) phases of growth. (F) CLS of W303, shy1 and C199 strains. (G and H) Cell respiration of W303, cox5a and cyc1 strains during exponential (G) and stationary (H) phases of growth. (I) CLS of W303, cox5a and cyc1 strains. Error bars represent the mean ± SD with p values denoted by * = p <0.05 and ** = p <0.01.

Measurements of ATP levels at day 0 in stationary phase showed that respiratory null rho0 cells have only ~4% of wild-type while cells respiring above the threshold such as Δcox5a cells have levels even slightly increased (~120%, Figure S3). Therefore, cellular respiratory rates correlate with the energetic state of the cell when the cells reach the stationary phase.

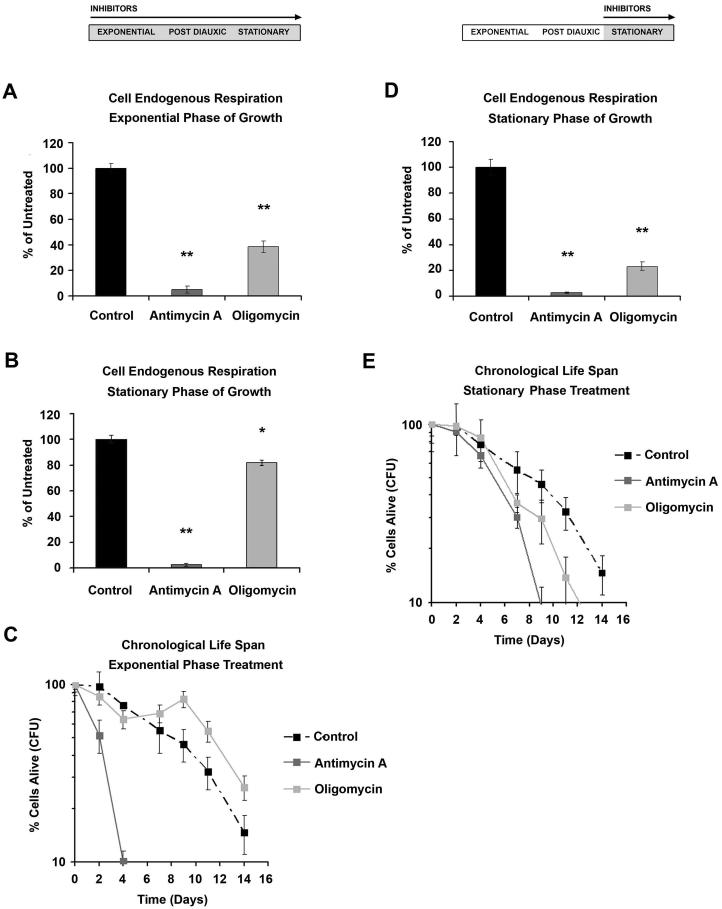

Stationary phase respiration is essential for standard CLS

To further evaluate the role of respiration in modulating yeast CLS and to assess its requirement during the different phases of growth, we took a pharmacological approach, supplementing the culture media with either 50μM antimycin A, a respiratory chain complex III inhibitor, or 10μM oligomycin, a specific mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitor. Under these conditions, antimycin A completely inhibited respiration both when supplemented at the exponential growth phase and maintained throughout the experiment or when added at the beginning of stationary phase only (at 72 h) (Figure 2A and D). In contrast, when the same experiment was done with 10μM oligomycin, respiration commenced at a rate 40% that of untreated cells when added at the exponential phase and 10-20% when added at the stationary phase (Figure 2A and D). The effects of these inhibitors on respiration resembled those induced by mutations that totally (rho0 or cyc3) or partially (cox5a or cyc1) limit cell respiration.

Figure 2. Effect of mitochondrial respiratory inhibitors on yeast CLS.

(A and B) Cell respiration during exponential (A) and stationary (B) phases of growth of W303 cells treated with 50μM antimycin A or 10μM oligomycin through the exponential and stationary phases. (C) CLS of W303 strain treated with 50μM antimycin A (AMA) or 10μM oligomycin (OLI) through the exponential and stationary phases. (D) Cell respiration during the stationary phase of growth of W303 strain treated with 50μM antimycin A or 10μM oligomycin, through only the stationary phase (E) CLS of W303 strain treated with 50μM antimycin A or 10μM oligomycin through only the stationary phase. Error bars represent the mean ± SD with p values denoted by *= p <0.05 and **= p <0.01.

Addition of antimycin A starting at the exponential phase severely limited CLS as reported (Fabrizio et al., 2003), similar to the rho0 mutation (Figure 2C), while supplementation of oligomycin had no effect on CLS, similar to the results obtained with cox5a and cyc1 . Different results where obtained when the respiratory inhibitors were added only during the stationary phase, as opposed to being present in both exponential and stationary phases. That is antimycin A reduced CLS from 14 days in non-treated cells to 8 days, and oligomycin only slightly reduced CLS (maximum 12 days) (Figure 2E) despite respiration being 25% of normal. These results show that although respiration during the stationary phase is essential for standard wild-type CLS, the absence or limitation of respiration exclusively during this phase has a milder effect on CLS than when respiration is curtailed in both the exponential and stationary phases.

Cell-extrinsic factors are not responsible for the shorter CLS of respiratory mutant stains

Because acetic acid produced during ethanol metabolism has been postulated to create a toxic environment for yeast cells that limits yeast CLS (Burtner et al., 2009; Kaeberlein, 2010), we sought to determine whether in respiratory-deficient mutants CLS inversely correlates with acetic acid levels produced during growth. The pH of the culture media after 72 h of growth of rho0, cyc3, shy1 and C199 respiratory-mutant strains was significantly less acidic (3.30) than for wild-type cells (2.75). Furthermore, the amount of acetic acid produced by these respiratory-deficient strains is actually ten-fold lower than by wild-type cells (Figure 3A) thus eliminating this molecule as the factor responsible for their shorter lifespan. To further eliminate a role of cell-extrinsic factors on limiting CLS in cells respiring below the critical threshold, we performed a media-swap experiment between W303 wild-type (rho+) and rho0 cells. The strains were grown to stationary phase and, at this point, cultures were centrifuged, media was exchanged and CLS analyzed. Control wild-type and rho0 cells in their own media reproduced their typical survival curve and CLS (Figure 3B). On the contrary, rho0 cells transferred to wild-type media displayed an even shorter lifespan, while the CLS of rho+ cells switched to rho0 media was significantly extended (Figure 3B). We therefore conclude that the shorter lifespan of cells respiring below the critical threshold is due to cell intrinsic factors.

Figure 3. Regulation of CLS by mitochondrial function is acetic-acid independent.

(A) Determination of acetic acid concentration in the growth media of the indicated strains. (B) CLS of W303 (rho+) or rho0 strains in their original media or subjected to media swap in the stationary phase. (C) CLS of W303, cox5a and cyc1 strains in the presence of buffered SDC media. (D) CLS of W303 strains grown in buffered SDC medium, treated with 50μM antimycin A (AMA) or 10μM oligomycin (OLI) from inoculation (Exp) or stationary phase (Sta) until the termination of the experiment. Error bars represent the mean ± SD.

On another approach to eliminate the influence of acetic acid accumulation, we chronologically aged respiratory-competent and -deficient strains in buffered media (pH 4.7). In these conditions, CLS of wild-type cells is significantly extended although the cells continue to lose viability over time (Burtner et al., 2009). Here, we wanted not only to confirm that the rapid decline in survival of strains with respiratory rate below the capacity threshold is acetic acid-independent. We also sought to test whether we had failed to observe a difference between the survival of wild-type cells and cells that retain 40-50% respiratory capacity because the presence of acetic acid in the media could mask the differences. As expected, when grown in buffered media, the CLS of all the strains was significantly longer than in non-buffered conditions (Figure 3C). Noticeably, although rho0 cells doubled their CLS, it was significantly shorter than for wild-type cells which was extended ~2.5-fold (Figure 3C and 1C). The cox5a strain had CLS comparable or even slightly longer than wild-type cells (Figure 3C), thus confirming that 40-50% of cell respiration is enough to sustain wild-type CLS. Pharmacological treatments of wild-type cells during the exponential phase in buffered media confirmed the results obtained with the mutant strains (Figure 3D). CLS extension by buffering the medium is probably accounted for by acetic acid quenching as mentioned earlier. However another important contributing factor, probably most significant for respiratory null mutant strains, is the decrease in energy expenditure required to maintain the internal cellular pH during the stationary phase, which has been estimated to account for 40-60% of all energy spent by the cells (Serrano, 1991).

Finally, we used the same media-buffered conditions to test the effect of complete or partial pharmacological respiratory inhibition exclusively during the stationary phase. Partial respiratory inhibition with oligomycin was enough to shorten maximum CLS from 28 to 23 days, while complete inhibition with antimycin A further reduced it to 16 days (Figure 3D). These results confirmed that respiration during the exponential and stationary phases is essential for standard wild-type lifespan.

ROS-independent effects of lower respiration on CLS

To determine whether ROS could be responsible for the shorter CLS of mutant strains respiring below the critical threshold, we estimated the amount of ROS in these strains using the fluorescent probe dihydroethidium (DHE) which preferentially detects superoxide (Pan et al., 2011). As expected, in rho0 and cyc3 cells unable to respire, ROS levels were significantly lower that in wild-type cells during both phases of growth (Figure 4A), and thus increased ROS accumulation in these strains does not appear to be responsible for their limited CLS. Similar low ROS levels were measured for cox5a and cyc1 cells (Figure 4B) that have wild-type CLS.

Figure 4. ROS production during growth does not affect yeast CLS.

(A and B) ROS production determined as DHE fluorescence in the indicated strains during exponential or stationary phases of growth. (C and D) ROS production determined as DHE fluorescence during exponential and stationary phase in W303 cells treated with 50μM antimycin A (AMA) or 10μM oligomycin (OLI) (C) through the exponential and stationary phases or (D) through only the stationary phase. Error bars represent the mean ± SD with p values denoted by * = p <0.05 and ** = p <0.01.

Antimycin A and oligomycin are known to promote ROS generation. Cells treated with either drug beginning at the exponential phase generated higher ROS levels than did untreated cells (Figure 4C). In both cases, increased ROS levels did not induce a detrimental effect on CLS either in buffered or non-buffered media when compared with mutant strains retaining similar respiratory capacity. However, when the cells where exposed to the two drugs exclusively during the stationary phase, their respiration was below the threshold required for standard CLS (Figure 2D) and their ROS production during this phase was significantly reduced (Figure 4D). Altogether, these results point to ROS-independent effects of lower respiration being responsible for their shorter CLS.

Caloric restriction alters the requirement of stationary phase respiration for extension of CLS

To determine whether respiratory thresholds also regulate CLS extension by caloric restriction, we examined cellular respiration of caloric-restricted (CR) wild-type cells during the exponential and stationary phases. CR led to 30% higher respiratory rate ((Oliveira et al., 2008), Figure 5A) and a more than two-fold extension of their maximum CLS up to 27 days (Figure 5C). While CR-treated strains reach the stationary phase at a time similar to non-restricted cells, they barely respire once they reach this point (Figure 5B). This observation suggests that the metabolic remodeling program that goes along with the entry of CR cells into the stationary phase alters the requirement of respiration during chronological aging. We subsequently used our models of respiratory deficiency to further explore this possibility. Respiratory null rho0 cells as well as wild-type cells treated with antimycin A beginning at the exponential phase had a similar CLS in non-CR and CR media (3.5 and 5.5 days for rho0 cells and 4 and 3.5 days for antimycin A-treated cells, respectively; Figure 5C and 5D), indicating that cells need a minimum respiration during growth to significantly benefit from the CR-induced CLS extension. However, when CR was performed in cox5a cells, their respiration also increased by 15-20% in the exponential phase but was barely detectable during the stationary phase (Figure 5A and B) and CLS extension by CR was similar to wild-type cells (Figure 5C). Additionally, CR cells treated with oligomycin beginning at the exponential phase exhibited 45% of wild-type respiration during growth and very poor respiration during the stationary phase (Figure 5A and B), but were still able to achieve a wild-type CLS extension (Fig 5D). Thus, the CLS of strains with respiratory capacity above the critical threshold during growth are extended similarly to wild-type strains by CR. Consistent with the CR effect on longevity involves shutting down respiration during the stationary phase, supplementation of CR cultures with antimycin A or oligomycin at day 0 (72h of growth) did not affect CLS (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate CLS under caloric restriction.

(A and B) Cell respiration during exponential (A) and stationary (B) phases of growth of W303, cox5a and W303 strains treated with 10μM oligomycin through the exponential and stationary phases. Yeast were grown in regular (Non-CR) or caloric restriction (CR) SDC media. (C) CLS of W303, rho0 and cox5a strains grown under caloric restriction (CR). (D) CLS of W303 strain grown under caloric restriction (CR) treated with 50μM antimycin A (AMA) or 10μM oligomycin (OLI) from inoculation (Exp) or stationary phases (Sta) until the termination of the experiment. Error bars represent the mean ± SD. (E) CLS of tor1Δ strain treated as in panel (D)

Deletion of TOR1 does not affect the respiratory thresholds that modulate CLS

To investigate the respiratory requirements for CLS extension by inhibition of the TOR pathway we used a tor1Δ strain and treated it with oligomycin or antimycin A either starting at the growth phase or only during stationary phase. Treatments starting at the exponential growth phase produced results similar to those obtained in CR conditions: oligomycin-treated cells lived longer while antymicin-treated cells did not benefit from the tor1 mutation and have a significantly shorter CLS (Fig. 5E). However, contrary to CR-treatment, tor1Δ strains were sensitive to the OXPHOS inhibitors when supplemented in the stationary phase. Thus, CR-treated cells are less dependent on mitochondrial respiration during stationary phase than tor1Δ cells.

Increasing mitochondrial respiration during growth is not sufficient to extend CLS

To obtain a CR- and tor1Δ-independent view of how increased mitochondrial respiration during exponential growth could modulate CLS, we used a wild-type strain overexpressing (OE) HAP4 (Ocampo et al., 2010). Hap4 is the catalytic subunit of the Hap2,3,4,5 transcriptional complex known to play an important role in globally activating transcription of nuclear genes involved in mitochondrial respiration during transition from fermentation to respiration. The HAP4 OE strain respired at a rate 150% of wild-type during growth and 50% during the stationary phase (Figure S4). HAP4 OE has been reported to slightly extend CLS when the cells were transferred to water upon reaching stationary phase (Piper et al., 2006). However, in our experimental conditions, we observed a slightly negative effect that could be explained by the fact that HAP4 OE cells produce higher levels of acetic acid than wild-type cells (Figure S4).

Mitochondria from the HAP4 OE strain are just slightly uncoupled, but they produce more ROS resulting from their high respiratory rate during exponential growth (Figure S4). However, during the stationary phase all these parameters and ATP content are similar to those of the wild-type strain (Figure S4). CR-treated strains also have higher respiration, slightly depolarized mitochondrial membranes and produce large amounts of ROS during exponential phase. But in the stationary phase they have very low respiration, ~80% of wild-type ATP levels, hyperpolarized mitochondria and significantly lowered ROS production (Figure S4). Thus, HAP4 OE fails to extend CLS for reasons other than increased uncoupling and lowered intracellular energy availability. Mitochondrial uncoupling however is not necessarily deleterious. Mild uncoupling during growth and stationary phase extends CLS of wild-type cells (Barros et al., 2004; Pan et al., 2011), while complete uncoupling during the stationary phase dramatically reduces CLS (Figure S5).

CR induces a metabolic remodeling during the transition to stationary phase that is different than in HAP4 OE cells. It must be noted that contrary to CR or the tor1Δ mutation, HAP4 OE induces an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis that is not accompanied by a general increase in expression of genes involved in either stress response or metabolism of energy reserves (Lascaris et al., 2003). These results indicate that enhanced mitochondrial respiration during growth is not sufficient to extend CLS. Increased respiration needs to be accompanied by metabolic remodeling that slows down energy consumption and enhances cell protection systems during the stationary phase like that achieved by CR or reduced TORC1 signaling.

Respiratory thresholds modulate CLS, in part, by regulating stress resistance and the metabolism of energy reserves?

Lastly, we explored whether mitochondrial function regulates stress resistance mechanisms and the accumulation and consumption of reserve energy sources that sustain life in the stationary phase (Longo and Fabrizio, 2002). The results presented in Figure 6A show that when rho0 and cyc3 cells reach the stationary phase they are less resistant to oxidative (1h in 100mM H2O2) and heat-shock (10 min at 55°C) stresses than wild-type cells or cells respiring above the 40% threshold, such as cox5aΔ and Δcyc1. However, we did not find significant differences in SOD1/2 activity among wild-type, rho0, and Δcox5a strains during growth (Figure S6A).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial dysfunction curtails yeast CLS by decreasing stress resistance and altering the reserve nutrients metabolism.

(A) Hydrogen peroxide and heat stress resistance of W303, rho0, cyc3, cox5a and cyc1 strains at day 0 during the stationary phase. (B) Time-course of glycogen and trehalose content during the stationary phase in W303, rho0 and cox5a cells. (C and D) Time-course of glycogen and trehalose content during the stationary phase of W303 cells treated with 50μM antimycin A (AMA) or 10μM oligomycin (OLI), (C) from inoculation (Exp) or (D) stationary phases (Sta) until the termination of the experiment. (E-F-H-I) CLS of (E) W303 cells, (F) rho0 cells, (G) W303 cells grown under CR and (H) tor1Δ cells grown in SDC medium supplemented with trehalose at the moment of inoculation (Exp) or at the stationary phase (Sta). Error bars represent the mean ± SD. (G) Hydrogen peroxide and heat stress resistance of W303 and rho0 strains grown in the presence or absence of trehalose at day 0 during the stationary phase.

Storage carbohydrates, mainly glycogen and trehalose, are used as energy sources during stationary phase. As a consequence, mutants unable to accumulate or utilize them have significantly shorter CLS (Favre et al., 2008; Samokhvalov et al., 2004). Respiratory null strains have defective trehalose synthesis and, although they accumulate high levels of glycogen during exponential growth, they readily mobilize it as soon as glucose is exhausted in the medium (Enjalbert et al., 2000). In agreement with these observations, at −14h (58h after inoculation) we measured high levels of glycogen (70% of wild-type) and a significantly reduced amount of trehalose (50% of wild-type) in cells respiring below the 40% threshold (Figure S6B). A time-course analysis of glycogen and trehalose content during the stationary phase in wild-type and cox5a cells showed comparable amounts of these storage carbohydrates at days 0, 4 and 9 of stationary phase, with cox5a cells perhaps having slightly more. Glycogen and trehalose content progressively decreased following similar kinetics in both strains as they were used during the stationary phase (Figure 6B). However, in rho0 cells, storage carbohydrate content was already low at day 0 as reported (Enjalbert et al., 2000) and basically exhausted after day 4 (Figure 6B). A similar tendency was measured in our pharmacological models (Figure 6C and D). Cells treated with antimycin A during the exponential phase exhausted their storage carbohydrates soon after reaching the stationary phase, while oligomycin-treated cells metabolized them as did wild-type cells (Figure 6C). In cells treated with antimycin A or oligomycin during the stationary phase, the rate of storage mobilization inversely correlated with the amount of residual respiration (Figure 6B). Our results show a striking correlation between stored carbohydrate content and cell survival. Wild-type and cox5a strains that have a maximum CLS of ~11 days already consumed approximately 80% of their stored carbohydrates by day 9 (Figure 6B). Respiratory-deficient strains, which rapidly mobilize their stored carbohydrates during stationary phase have shorter CLS, suggesting this may underlie their shortened lifespan. To further test this hypothesis, we measured CLS of respiratory-deficient and competent strains cultured in media supplemented with 1% trehalose. Trehalose supplementation did not significantly extend CLS of the wild-type strain (probably limited by acetic acid accumulation; Figure 6E) independently of the growth phase in which was added. Instead, trehalose supplementation only during the stationary phase, when trehalose assimilation is known to be poor (Jules et al., 2004), slightly extended CLS of rho0 cells. Significantly, the CLS of rho0 cells was extended beyond wild-type length when trehalose was added beginning in the exponential growth phase (Figure 6F), when it can be efficiently assimilated (Jules et al., 2004). As expected, rho0 cells grown in trehalose supplemented media have a higher resistance to stress than cells pre-grown in non-supplemented media (Figure 6G). This observation significantly strengthens the relationship between respiratory thresholds, nutrient stores and stress resistance in stationary phase.

In yeast, interventions that extend CLS such as CR or the tor1Δ mutation are known to induce an accumulation of storage carbohydrates (Francois and Parrou, 2001). Trehalose supplementation did further extend CLS of CR and tor1Δ cells (Figure 6H and I) whose CLS is less limited by acetic acid toxicity than for wild-type cells. Therefore, also under these CLS-extending conditions, exhaustion of nutrient stores contributes to limit the maximum longevity of yeast strains.

DISCUSSION

Despite some controversies surrounding the mitochondrial theory of aging, it is widely accepted that mitochondria play fundamental roles in the mechanisms of aging and lifespan extension. Here we have used genetic and pharmacological yeast models of respiratory deficiency to determine the minimum respiratory capacity required to sustain standard wild-type CLS. While in agreement with previous reports indicating that respiration is essential for standard wild-type CLS (Aerts et al., 2009; Bonawitz et al., 2006), our results show that yeast cells have a large reserve respiratory capacity to sustain CLS, as respiration only limits CLS when depleted below a ~40% of wild-type threshold (Figure 7). A fundamental aspect that determines yeast CLS is the ability of cells to remodel their metabolism from fermentation to respiration when glucose levels decline during the diauxic shift. This remodeling is also accompanied by a significant reduction in metabolic rate (Fabrizio and Longo, 2007). We show that strains that respire above the critical threshold during growth are able to properly adjust their metabolic rate after the diauxic shift in a manner similar to that of wild-type strains. In contrast, strains respiring below the threshold during growth have extremely poor respiratory capacity in the stationary phase and very short CLS. Further, our results show that respiratory defects are less detrimental when produced only in the stationary phase, once yeast have accumulated nutrient stores during growth and undergone their metabolic remodeling during the diauxic shift.

Figure 7. Model of CLS regulation by mitochondrial respiration.

Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast CLS and its extension by caloric restriction (see explanation in the text). For simplicity, the effect of cell extrinsic factors is not included.

What could be the key factor responsible for the shorter CLS of mutant strains with respiratory rates below the critical capacity threshold? Acetic acid-induced apoptosis has been proposed as a CLS limiting factor. While there is no doubt that acetic acid toxicity can potentially mask the effect of some longevity factors, so far mutations in several conserved nutrient-sensing pathways, including TORC1 (Pan et al., 2011) and RAS2 (Burtner et al., 2009) have been shown to extend CLS through acetic acid-independent mechanisms. Similarly, results obtained from measurements of acetic acid concentrations, media swap experiments and determinations of CLS in buffered media have allowed us to conclude that mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate CLS in a cell-intrinsic and acetic acid-independent manner.

Our results also indicate that the shorter CLS of strains with respiratory capacity below the critical threshold is independent of ROS accumulation. The concept of mitochondrial ROS exclusively as the toxic molecular inducers of cellular damage and responsible for disease and aging has been challenged over the last few years. Although ROS are known to limit the long-term survival of yeast cells during CLS and can have a detrimental effect during aging of species of fly, worm and mouse, a growing amount of evidence supports a role for mitochondrial ROS as signaling molecules with hormetic effects on longevity (Pan et al., 2011; Ristow and Schmeisser, 2011; Yang and Hekimi, 2010). The results presented here further indicate that the relationship between respiration, ROS and lifespan is complex. Our comparison of yeast strains with different genetic backgrounds suggests a correlation between respiratory capacity, mitochondrial ROS generation and CLS. Strains with high respiration and ROS production have longer CLS which is curtailed by increased SOD2 levels while strains with low respiration and ROS production have shorter CLS and can significantly benefit from additional exogenous ROS or tor1Δ-induced endogenous ROS to significantly extend their CLS (Pan et al., 2011). Our data support a model in which ROS signaling and the respiratory thresholds described here are complementary aging models that utilize two distinct mechanisms to achieve the same adaptive endpoint: increased stress resistance, efficient use of energy stores, and likely other beneficial effects in stationary phase, which extends CLS.

When yeast cells enter the stationary phase they anticipate the shortage of glucose and have enacted cell-protection systems that allow them to survive. In dividing cells, mitochondrial function is dispensable for normal expression of anti-oxidant enzymes but it is required for resistance to oxidative stress (Grant et al., 1997). Here, we have shown that respiratory-deficient cells are very sensitive to oxidative and thermal stresses when they reach the stationary phase despite having normal levels of SOD1/2. The stress sensitivity could be related to a defect in an energy-requiring process needed for either ROS detoxification or oxidative damage repair that cannot be fulfilled in the absence of respiration as previously proposed (Grant et al., 1997). Furthermore, cells respiring below the critical 40% threshold have altered metabolism of stored nutrients. Respiratory-deficient cells accumulate high amounts of glycogen during growth, but their synthesis of trehalose, which occurs when glucose is exhausted and cells start utilizing ethanol, is known to be inefficient (Enjalbert et al., 2000). Trehalose plays additionally roles as a stress protectant in biological systems (Francois and Parrou, 2001). Therefore, its poor synthesis and rapid depletion in respiratory-deficient cells probably contributes to their stress sensitivity. Trehalose is also essential to enable yeast cells to survive starvation conditions and then rapidly proliferate upon return to favorable growth conditions by fueling cell cycle progression (Shi et al., 2010). However, respiratory-deficient cells are not just impaired in cell cycle re-entry, as shown by the fact that their survival curve is similar whether constructed by counting colony formation units or by counting propidium iodide positive cells by flow cytometry (Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011). Glycogen is mobilized faster than the more stable trehalose. Both of these reserve carbohydrates are quickly consumed when the cells reach the stationary phase because, in the absence of respiration, yeast must rely on fermentation, which generates a 14-fold lower energetic yield. Glycogen and trehalose are virtually exhausted in respiratory-deficient cells by the end of their CLS, thus suggesting that starvation is an important factor limiting their survival. In support of this conclusion, trehalose supplementation of the growth media enhances the stress-resistance capacity of respiratory null strains and significantly extends their CLS.

In yeast, CR extends CLS in part through the down-regulation of signaling pathways involving nutrient-responsive kinases such as Ras/cAMP/PKA, TOR and Sch9, which promote the expression of stress-response genes and accumulation of storage carbohydrates (Wei et al., 2008). CR also involves a metabolic remodeling including the shift from fermentation to respiration which is essential for CLS extension (Oliveira et al., 2008). In yeast, CR is modeled by growing the cells in 0.5% glucose which minimizes glucose repression of OXPHOS genes, thus allowing the cells to increase their respiratory capacity during growth. However, the metabolic remodeling occurring during the diauxic shift allows CR cells to dramatically reduce their metabolic rate in the stationary phase and hence consume their stored nutrients at a rate slower than cells grown in 2% glucose (Goldberg et al., 2009). Our results show that at the beginning of the stationary phase, CR cells retain only 5-10% of the respiratory capacity of non-CR cells and that respiration during the stationary phase is not essential to achieve maximal CLS extension. In addition, CR-treated cells are less dependent on mitochondrial respiration during stationary phase than tor1Δ cells. However, cells must respire during growth above a ~40% threshold to benefit from either CR- or tor1Δ-induced CLS extension (Figure 7). W303 CLS extension by CR is not significantly affected by SOD2 OE (Figure S7) further indicating differences between tor1Δ and CR-induced longevity mechanisms. Both CR and tor1Δ alter different aspects of mitochondrial function during exponential growth, and hence they differ in their requirements for respiratory thresholds. Importantly and in agreement with results in puf3Δ strains, which have increased OXPHOS abundance and respiration but wild-type CLS (Chatenay-Lapointe and Shadel, 2011), our results show that increased respiration during growth (i.e. by HAP4 OE) is not sufficient to extend CLS if it is not accompanied by an enhancement of cell protection systems that promote survival in the stationary phase as for tor1Δ and CR-treated cells.

We believe our results are relevant to the physiology of aging of higher organisms. Although some effects of CR on mammalian metabolism remain controversial, it is accepted that CR increases mitochondrial biogenesis (Lopez-Lluch et al., 2006; Nisoli et al., 2005), which has been associated with an accumulation of partially uncoupled mitochondria that maintain cellular ATP synthesis with lower ROS production (Lopez-Lluch et al., 2006). Additionally, several studies (Ferguson et al., 2008; Knight et al., 2011) have shown that long term CR decreases metabolic rate in rodents as it does in yeast. Accumulation and efficient mobilization of nutrient stores, one of the hallmarks of yeast longevity, is also relevant to stress responses across species. While yeast accumulate carbohydrates (glycogen/trehalose), mammals can increase fat mass as a stress response to the uncertainty of food availability, such in anticipation of the winter, which is particularly important for hibernating animals. Therefore it is possible that a conserved response to starvation stress is to accumulate carbon sources that would maximize long-term survival and to utilize them efficiently later in life (Longo and Fabrizio, 2002). Furthermore, the beneficial effect of trehalose on longevity is not restricted to yeast. Trehalose treatment extends lifespan of C. elegans even when administered late in life (Honda et al., 2010). Also, by acting as a chemical chaperone, trehalose alleviates polyglutamine-induced pathology in mice (Tanaka et al., 2004) and thus, in principle, it could be a promising health-promoting therapeutic compound. Finally, energy and respiratory thresholds have been described in human mitochondrial physiology and disease as individual respiratory enzyme activities can be inhibited to varying degrees before observing an OXPHOS phenotype. Respiratory thresholds to support cellular life probably vary for every tissue, which in turn likely changes the importance of other factors like ROS signaling in a tissue-specific manner. Respiratory deficiencies underlie the pathogenic mechanisms of classical mitochondrial disorders and are also frequently associated with age-related pathology such as neurodegeneration. Thus it is temping to speculate that interventions mimicking CR might lower the energetic thresholds of critical affected tissues which, if accompanied by an enhancement of cellular protection systems, could extend health span in normal and diseased individuals.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast strains, culture conditions and chronological lifespan determination

The S. cerevisiae strains used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Chronological lifespan determinations were performed on cells grown in liquid synthetic complete medium containing glucose (SDC) by the colony formation unit (CFU) assay (Ocampo and Barrientos, 2011).

Chemical treatments

Cell cultures were supplemented with either 50μM antimycin A (Sigma) or 10μM oligomycin (Sigma). The treatments started either in the exponential phase when the cells were first inoculated or in the stationary phase 72h after inoculation. Fresh doses of the inhibitors were added every other day. In untreated cultures, an equal volume of drug vehicle (ethanol) was added as a control.

Cell respiration

Endogenous cell respiration was assayed polarographically using a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, UK) as described (Barrientos et al., 2002).

Miscellaneous Procedures

Media neutralization and Media-swap experiments as well as ROS quantification using dihydroethidium (DHE) were performed as described (Pan et al., 2011). Enzymatic detection of acetic acid was performed using Megazyme Acetic Acid Kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantification of glycogen and trehalose was performed by quantifying glucose release upon specific enzymatic digestion. Stress resistance assays were performed by testing the ability of cells to grow in solid complete medium following exposition to 100mM H2O2 for 1h or to 55°C for 5 min. All miscellaneous methods are explained in detail in the supplemental material.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were done at least in triplicate. The number of CFU at day 0 (72 hours after inoculation) was considered to be the initial survival baseline (100%) and was used to calculate the percentage of survival at the different later time points. All data is presented as means ± SD of absolute values or percent of control. Values were compared by Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Brant Watson and Dr. Flavia Fontanesi for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by a Research Challenge grant from the Florida Department of Health / James & Esther King Biomedical Research Program (to A.B.) and NIH-RO1 GM071775-06 (to A.B.), grants from the U.S. Army Research Office and the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research (to G.S.S). E.A.S. was supported by NIH pre-doctoral Genetics training grant T32 GM007499.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes 7 Figures, 1 Table and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

REFERENCES

- Aerts AM, Zabrocki P, Govaert G, Mathys J, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Madeo F, Winderickx J, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to reduced chronological lifespan and increased apoptosis in yeast. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Korr D, Tzagoloff A. Shy1p is necessary for full expression of mitochondrial COX1 in the yeast model of Leigh’s syndrome. EMBO J. 2002;21:43–52. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros MH, Bandy B, Tahara EB, Kowaltowski AJ. Higher respiratory activity decreases mitochondrial reactive oxygen release and increases life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49883–49888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Chatenay-Lapointe M, Pan Y, Shadel GS. Reduced TOR signaling extends chronological life span via increased respiration and upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab. 2007;5:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Rodeheffer MS, Shadel GS. Defective mitochondrial gene expression results in reactive oxygen species-mediated inhibition of respiration and reduction of yeast life span. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:4818–4829. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02360-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Shadel GS. Rethinking the mitochondrial theory of aging: the role of mitochondrial gene expression in lifespan determination. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1574–1578. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4457. Epub 2007 May 1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A molecular mechanism of chronological aging in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1256–1270. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatenay-Lapointe M, Shadel GS. Repression of mitochondrial translation, respiration and a metabolic cycle-regulated gene, SLF1, by the yeast Pumilio-family protein Puf3p. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert B, Parrou JL, Vincent O, Francois J. Mitochondrial respiratory mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae accumulate glycogen and readily mobilize it in a glucose-depleted medium. Microbiology. 2000;146:2685–2694. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Liou LL, Moy VN, Diaspro A, Valentine JS, Gralla EB, Longo VD. SOD2 functions downstream of Sch9 to extend longevity in yeast. Genetics. 2003;163:35–46. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Longo VD. The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;371:89–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-361-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre C, Aguilar PS, Carrillo MC. Oxidative stress and chronological aging in glycogen-phosphorylase-deleted yeast. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:1446–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M, Rebrin I, Forster MJ, Sohal RS. Comparison of metabolic rate and oxidative stress between two different strains of mice with varying response to caloric restriction. Exp. Gerontol. 2008;43:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois J, Parrou JL. Reserve carbohydrates metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2001;25:125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisne M, Becam AM, Verdiere J, Herbert CJ. A ‘natural’ mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains derived from S288c affects the complex regulatory gene HAP1 (CYP1) Curr. Genet. 1999;36:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s002940050490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AA, Bourque SD, Kyryakov P, Gregg C, Boukh-Viner T, Beach A, Burstein MT, Machkalyan G, Richard V, Rampersad S, et al. Effect of calorie restriction on the metabolic history of chronologically aging yeast. Exp. Gerontol. 2009;44:555–571. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CM, MacIver FH, Dawes IW. Mitochondrial function is required for resistance to oxidative stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y, Tanaka M, Honda S. Trehalose extends longevity in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2010;9:558–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jules M, Guillou V, Francois J, Parrou JL. Two distinct pathways for trehalose assimilation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:2771–2778. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.2771-2778.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M. Lessons on longevity from budding yeast. Nature. 2010;464:513–519. doi: 10.1038/nature08981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight WD, Witte MM, Parsons AD, Gierach M, Overton JM. Long-term caloric restriction reduces metabolic rate and heart rate under cool and thermoneutral conditions in FBNF1 rats. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011;132:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascaris R, Bussemaker HJ, Boorsma A, Piper M, van der Spek H, Grivell L, Blom J. Hap4p overexpression in glucose-grown Saccharomyces cerevisiae induces cells to enter a novel metabolic state. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-4-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Fabrizio P. Regulation of longevity and stress resistance: a molecular strategy conserved from yeast to humans? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:903–908. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lluch G, Hunt N, Jones B, Zhu M, Jamieson H, Hilmer S, Cascajo MV, Allard J, Ingram DK, Navas P, de Cabo R. Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:1768–1773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Falcone S, Valerio A, Cantoni O, Clementi E, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science. 2005;310:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1117728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A, Barrientos A. Quick and reliable assessment of chronological life span in yeast cell populations by flow cytometry. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011;132:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A, Zambrano A, Barrientos A. Suppression of polyglutamine-induced cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enhancement of mitochondrial biogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:1431–1441. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-148601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira GA, Tahara EB, Gombert AK, Barros MH, Kowaltowski AJ. Increased aerobic metabolism is essential for the beneficial effects of caloric restriction on yeast life span. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2008;40:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Schroeder EA, Ocampo A, Barrientos A, Shadel GS. Regulation of yeast chronological life span by TORC1 via adaptive mitochondrial ROS signaling. Cell. 2011;13:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper PW, Harris NL, MacLean M. Preadaptation to efficient respiratory maintenance is essential both for maximal longevity and the retention of replicative potential in chronologically ageing yeast. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006;127:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.05.004. Epub 2006 Jun 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristow M, Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samokhvalov V, Ignatov V, Kondrashova M. Reserve carbohydrates maintain the viability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells during chronological aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2004;125:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R. Transport across yeast vacuolar and plasma membranes. In: Strathern EWJJN, Broach JR, editors. The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces. Genome dynamics, protein synthesis, and energetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: 1991. pp. 523–585. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Sutter BM, Ye X, Tu BP. Trehalose is a key determinant of the quiescent metabolic state that fuels cell cycle progression upon return to growth. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:1982–1990. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Jr., McClure JM, Matecic M, Smith JS. Calorie restriction extends the chronological lifespan of Saccharomyces cerevisiae independently of the Sirtuins. Aging Cell. 2007;6:649–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Machida Y, Niu S, Ikeda T, Jana NR, Doi H, Kurosawa M, Nekooki M, Nukina N. Trehalose alleviates polyglutamine-mediated pathology in a mouse model of Huntington disease. Nat Med. 2004;10:148–154. doi: 10.1038/nm985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifunovic A, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of ageing. J. Intern. Med. 2008;263:167–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Fabrizio P, Hu J, Ge H, Cheng C, Li L, Longo VD. Life span extension by calorie restriction depends on Rim15 and transcription factors downstream of Ras/PKA, Tor, and Sch9. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.