Abstract

ALG-2 is a penta-EF-hand Ca2+-binding protein and interacts with a variety of intracellular proteins. Two types of ALG-2-binding motifs have been determined: type 1, PXYPXnYP (X, variable; n = 4), in ALIX and PLSCR3; type 2, PXPGF, in Sec31A and PLSCR3. The previously solved X-ray crystal structure of the complex between ALG-2 and an ALIX peptide containing type 1 motif showed that the peptide binds to Pocket 1 and Pocket 2. Co-crystallization of ALG-2 and type 2 motif-containing peptides has not been successful. To gain insights into the molecular basis of type 2 motif recognition, we searched for a new hydrophobic cavity by computational algorithms using MetaPocket 2.0 based on 3D structures of ALG-2. The predicted hydrophobic pocket designated Pocket 3 fits with N-acetyl-ProAlaProGlyPhe-amide, a virtual penta-peptide derived from one of the two types of ALG-2-binding sites in PLSCR3 (type 2 motif), using the molecular docking software AutoDock Vina. We investigated effects of amino acid substitutions of the predicted binding sites on binding abilities by pulldown assays using glutathione-S-transferase -fused ALG-2 of wild-type and mutant proteins and lysates of cells expressing green fluorescent protein -fused PLSCR3 of wild-type and mutants. Substitution of either L52 with Ala or F148 with Ser of ALG-2 caused loss of binding abilities to PLSCR3 lacking type 1 motif but retained those to PLSCR3 lacking type 2 motif, strongly supporting the hypothesis that Pocket 3 is the binding site for type 2 motif.

Keywords: ALG-2, calcium-binding protein, computational prediction, protein-protein interaction, proline-rich motif

1. Introduction

Eukaryotes have a group of proteins that each possess a domain of five serially repeated helix-loop-helix Ca2+-binding motifs (EF-hands). The domain of approximately 170 amino acid residues encompassing the five EF-hand motifs is named a penta-EF-hand (abbreviated PEF) domain [1,2]. In humans, PEF domains are found in more than five proteins: ALG-2, peflin, sorcin, grancalcin and members of the classical calpain family [3]. A unique feature of the PEF is homo-dimerization or hetero-dimerization with closely related PEF proteins. X-ray crystal structural analyses of these PEF proteins revealed that the fifth EF hand (EF5) of each molecule parallels to form a major interface for dimerization [4].

ALG-2 was originally identified as one of the factors associated with cell death of mouse T cell hybridoma induced by stimulants such as T-cell receptor cross-linking, Fas, and glucocorticoid. It was thus named “apoptosis-linked gene 2” [5] and the gene name PDCD6 has been adopted from “programmed cell death 6”. ALG-2 associates with a number of cellular proteins in a Ca2+-dependent manner, such as ALIX [6,7], annexin A7 [8], annexin A11 [9], TSG101 [10], Sec31A [11,12], RBM22 [13], Scotin [14], PLSCR3 [15], PATL1 [16], ASK1 [17], Raf-1 [18] and mucolipin-1 [19]. Except for the last three proteins, ALG-2-interacting proteins have Pro-rich regions. Sequence comparison and mutational analyses of ALG-2-binding sites in ALIX, PLSCR3 and Sec31A have revealed the presence of at least two types of ALG-2-binding motifs in the Pro-rich regions. While type 1 motif (PXYPXnYP; X, variable residue; n = 4) is represented in ALIX and PLSCR3, type 2 motif (PXPGF) is represented in PLSCR3 and Sec31A [15,20]. Both motifs are found in spatially separated Pro-rich regions (ALG-2-binding site, ABS, 1 and 2) of PLSCR3 and their ALG-2 binding capacities have been experimentally demonstrated [15].

We previously solved the crystal structure of the complex between ALG-2 and a peptide of ALIX containing type 1 motif (ALIX ABS peptide: 799-QGPPYPTYPGYPGYCQ-814; agreement with motif being underlined) in the presence of Zn2+ instead of Ca2+ [21]. The peptide binds to two juxtaposed hydrophobic pockets named Pocket 1 and Pocket 2, which hold PPYP and YP, respectively. We attempted to co-crystallize ALG-2 and type 2 motif-containing peptides derived from PLSCR3 or Sec31A, but we failed. While the alternatively spliced isoform of ALG-2 (designated ALG-2ΔGF122) can bind peptides containing type 2 motif, it does not bind those containing type 1 motif [12,15]. The dissimilarity between the two motifs in the sequence as well as the capacity of binding to two isoforms suggests that type 2 motif is accepted by pockets different from Pocket 1 and Pocket 2. However, locations of new pockets have remained unidentified.

Calmodulin is the most extensively studied EF-hand-type Ca2+-binding protein. It shows a gross conformational change upon binding to its target peptides as if the peptides are wrapped around by the N-terminal lobe (EF1–EF2) and C-terminal lobe (EF3–EF4) of calmodulin [22]. On the other hand, the difference between the structure of ALG-2 and that in the complex with the ALIX peptide was found to be small [21]. Assuming that a similar mode of binding is taken by type 2 motif peptides, the Pro-rich motif peptides should bind to cavities or pockets on the protein surface that should be similar with those in the complex. In this study, we predicted a type 2 motif-binding pocket by computational approaches and evaluated the binding site by in vitro binding assays using amino acid-substituted mutants of ALG-2.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Prediction of Potential Binding Sites in the Dimer Molecule of ALG-2

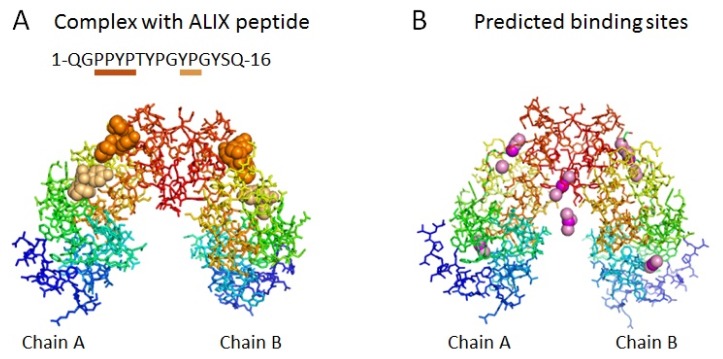

We employed a freely available on-line tool named MetaPocket 2.0 [23], which was designed to predict consensus sites in ranking by combining results of eight individually developed predictors including LIGSITEcsc [24], PASS [25], Q-SiteFinder [26], SURFNET [27], Fpocket [28], GHECOM [29], ConCavity [30] and POCASA [31]. We first examined efficacy of this combined computational approach by comparing the known binding sites in the crystal structure of Zn2+-bound form of des3-23ALG-2/ALIX ABS peptide complex (PDB ID: 2zne) with the binding sites predicted by MetaPocket 2.0 using the crystal structure of Ca2+-bound form of des3-20ALG-2 (PDB ID: 2zn9). As shown in Figure 1, the ALIX ABS peptides (panel A, orange spheres indicating PPYP and light orange spheres indicating YP, respectively) occupy two of the six predicted binding site clusters in chains A and B of ALG-2 dimer by MetaPocket 2.0 (panel B), demonstrating successful prediction. Two of the additionally predicted sites are formed at a crevice created between each molecule of ALG-2 dimer (chains A and B). Previous mutational analyses of ALG-2 showed that ALG-2Y180A (substitution of Y180 with alanine) lost both the ability to form a homodimer [32] and the ability to bind to ALIX but retained the ability to bind to PLSCR3 and Sec31A [15]. Thus, an authentic binding site for type 2 motif should be unaffected by dimerization. Since the crevice formed between chains A and B of ALG-2 dimer can be excluded, two other predicted sites more proximal to N-terminal regions (cyan to green in the rainbow colors) are promising.

Figure 1.

Ligand-binding sites in ALG-2 dimer. (A) Crystal structure of the Zn2+-bound form of des3-23ALG-2 in the complex with ALIX ABS peptide (PDB ID: 2zne). ALG-2 dimer molecules (chains A and B) are drawn by PyMol and displayed by stick models in rainbow colors (blue to red gradation from N-terminal to C-terminal regions). Orange and light orange spheres indicate PPYP and YP moieties of the ALIX peptide (underlined) bound to ALG-2. The ALIX peptide bound to chain B is shown for YP from chain D and for PPYP from chain H in two-fold crystallographically symmetric ALG-2 tetramer (chains A, B, E and F) that is in complex with four peptide molecules with two different binding patterns (chains C, D, G and H. see Supplementary file of 2zne_and_symmetry in PDB format). Zinc atoms are not shown. (B) Top six ranked ligand-binding sites predicted in the ALG-2 dimer (des3-20ALG-2, PDB ID: 2zn9) by MetaPocket 2.0 using chains A and B of PDB ID 2zn9. Spheres colored in magenta and light pink indicate predicted centers of ligand-binding sites by MetaPocket and top three sites by individual predictors, respectively. Calcium atoms are not shown.

2.2. Prediction of Binding Sites for Type 2 Motif in the Monomer Molecule of ALG-2

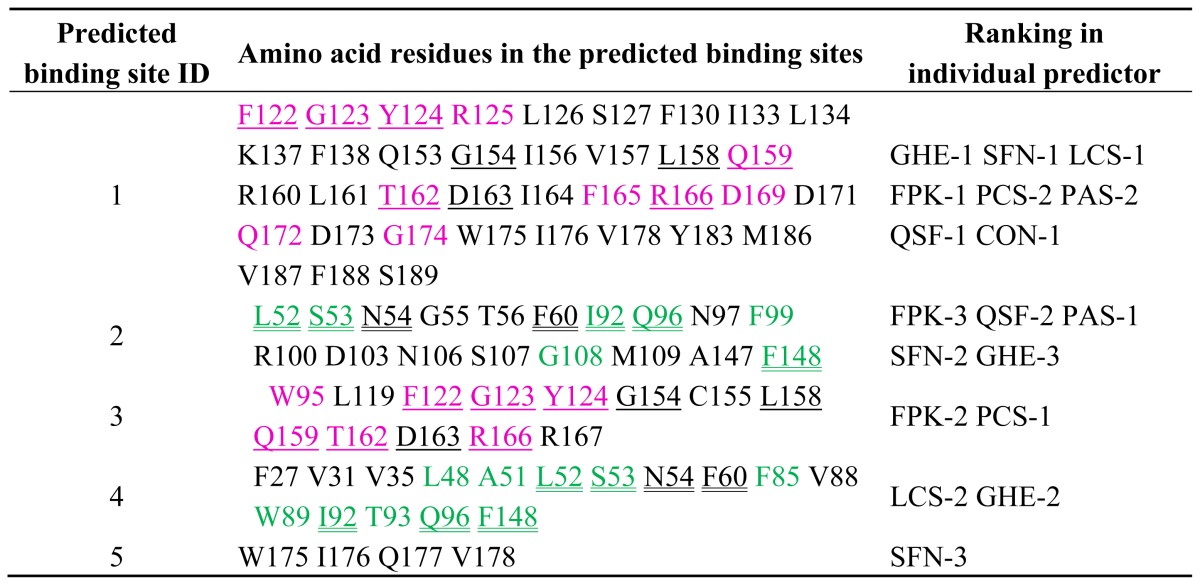

Prediction of potential binding sites for type 2 motif by MetaPocket 2.0 was further performed by using only chain A of the Ca2+-bound form of ALG-2 dimer as a query structure (PDB ID: 2zn9). The top five ranked sites (ID Nos. 1–5) are listed in Table 1. Amino acid residues are partially overlapped between ID Nos. 1 and 3 and between ID Nos. 2 and 4 (Table 1, underlined and double-underlined, respectively), suggesting juxtaposition of these sites. ID Nos. 1 and 3 contain residues known to interact with 3-PPYP and 11-YP of the ALIX peptide (1-QGPPYPTYPGYPGYSQ-16, interacting residues underlined) at previously named Pocket 1 and Pocket 2, respectively, in the crystal structure of the complex (Table 1, letters in magenta) [21]. As shown in the surface presentation in Figure 2, ID No. 1 (Pocket 1) and ID No. 3 (Pocket 2) are juxtaposed (left panels). Binding sites were also predicted in an area distantly located from these sites (bottom of front and side views). Residues of ID No. 2 (green) and ID No. 4 (cyan) partly merge (yellow) and create a pocket named Pocket 3, whose contour displayed at vertical section of line V1–V2 shows a concave shape (right panels). The relationship between ID numbers of the predicted potential binding sites and pocket numbers designated in this study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Potential ligand-binding sites in the monomer molecule of ALG-2 predicted by multiple computational algorithms. Chain A of PDB ID 2zn9 was searched for potential ligand-binding sites using MetaPocket 2.0 that combines the results of eight predicting methods. Predicted top five ranked binding sites (ID Nos. 1–5) and the residue numbers of amino acids that form the potential binding sites are listed. Letters in magenta in binding site ID Nos. 1 and 3 are residues known to interact with the ALIX peptide in the crystal structure (PDB ID 2zne, chains A and C). Letters in green in binding sites ID Nos. 2 and 4 are residues predicted to interact with a model type 2 motif peptide by simulation with AutoDock Vina and analyzed with LIGPLOT (See Table 3). Each residue overlapping between ID Nos. 1 and 3 and between ID Nos. 2 and 4 is indicated by an underline and double underline, respectively. Number following the hyphen indicates ranking in individual predictors used in MetaPocket 2.0: ConCavity (CON); Fpocket (FPK); GHECOM (GHE); LigsiteCS (LCS); PASS11 (PAS); POCASA (PCS); Q_SiteFinder (QSF); SURFNET (SFN).

Figure 2.

Potential ligand-binding sites predicted by MetaPocket 2.0 in the monomer molecule of ALG-2. Surface of chain A of PDB ID 2zn9 is drawn by PyMol and shown in three different views: front, side and bottom. Residues involved in forming the pockets of predicted potential binding sites (ID Nos. 1–4) are represented by different colors, and pocket numbers are assigned as indicated in Table 2. A view of the vertical section along the line V1–V2 in Pocket 3 is shown in the right lower panel where interior is painted in light gray.

Table 2.

Relationship between predicted binding site ID numbers and pocket numbers assigned in this study.

| Color | Predicted binding site ID number | Pocket number | |

|---|---|---|---|

| orange | 1 | Pocket 1 | |

| red | 3 | Pocket 2 | |

| salmon | 1 & 3 | Pockets 1 & 2 | |

| green | 2 | Pocket 3 | |

| cyan | 4 | Pocket 3 | |

| yellow | 2 & 4 | Pocket 3 |

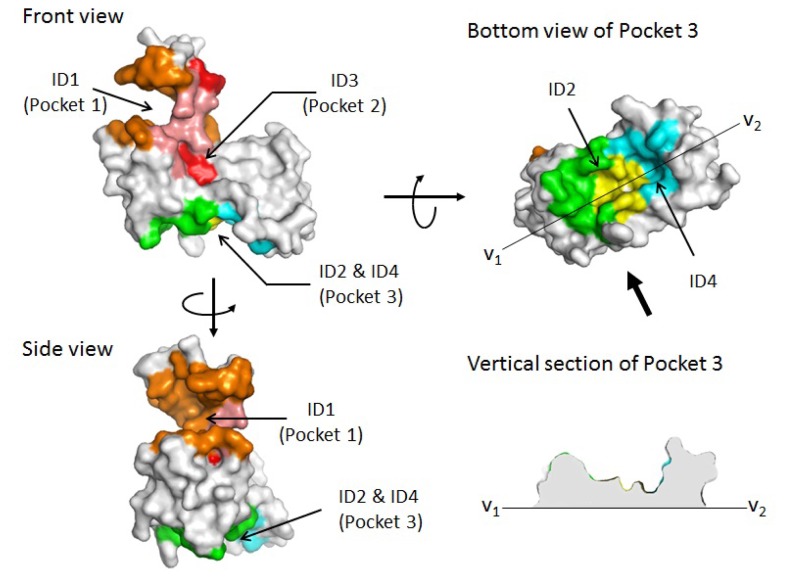

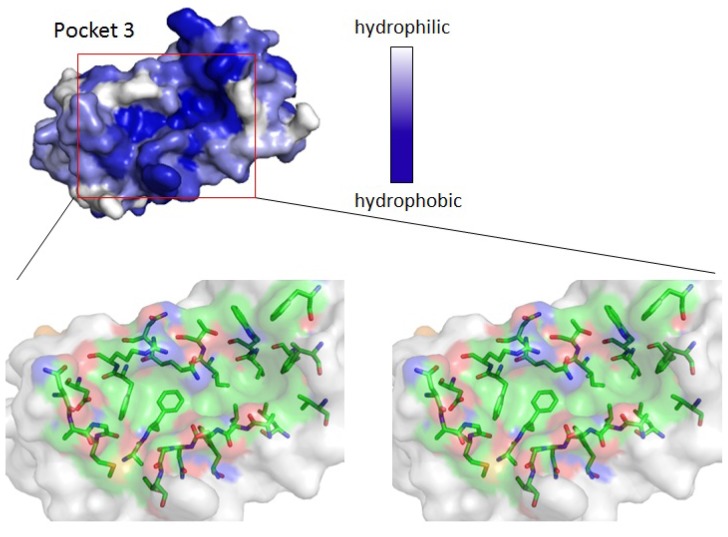

2.3. Docking Model of Type 2 Motif Peptide Binding to Hydrophobic Pocket 3

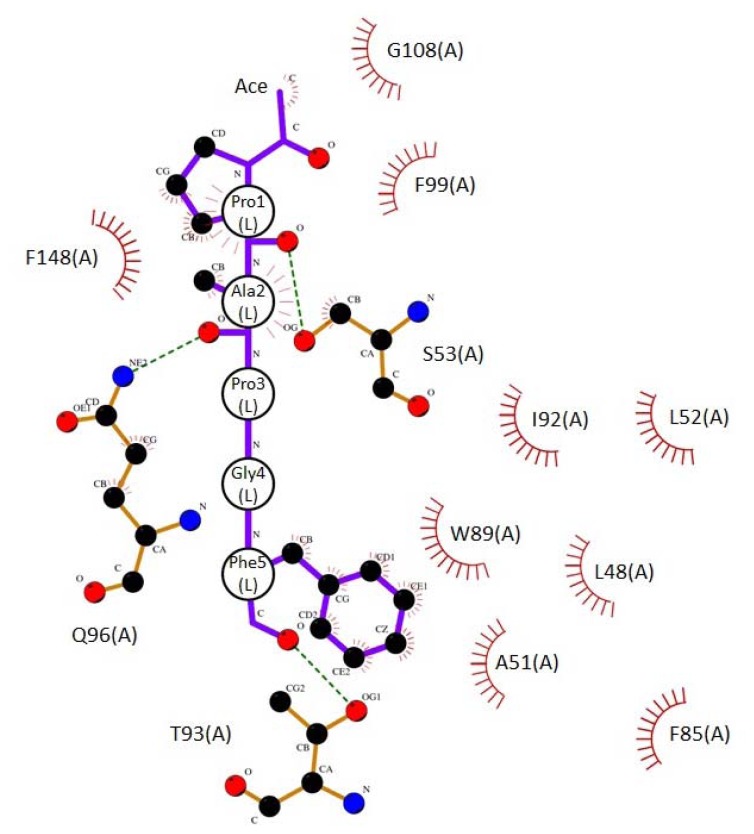

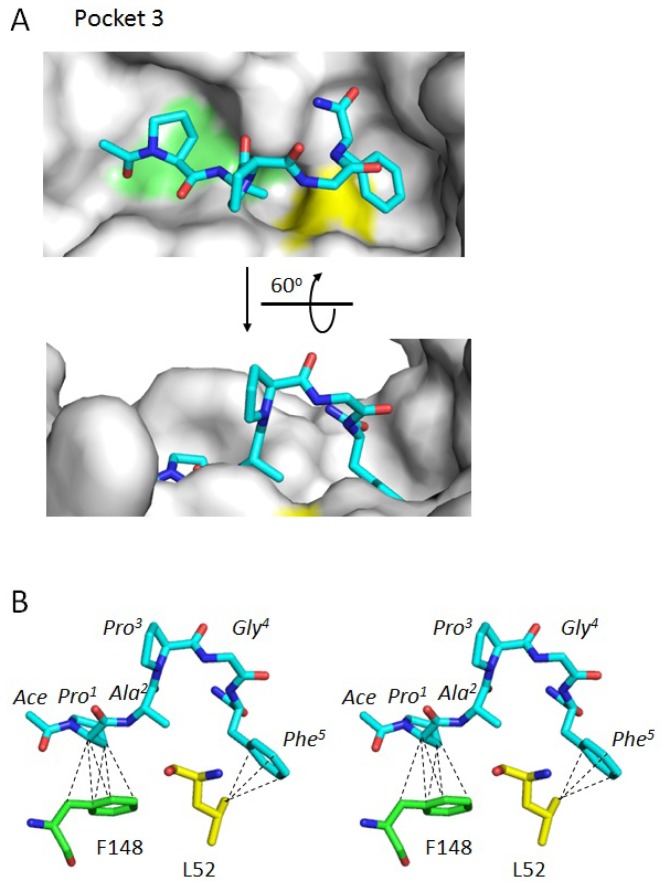

Side chains of amino acid residues comprising type 2 motif and those of neighboring residues are hydrophobic in PLSCR3 (41-QVPAPAPGFALFPS-54, ABM-2 underlined) and Sec31A (837-NPPPPGFIMH-846), suggesting hydrophobic interactions for binding between these ligands and ALG-2. As shown in the upper panel Figure 3, Pocket 3 has a high degree of hydrophobicity and it is created by amino acid residues with hydrophobic side chains (lower panels shown in stereoview). We constructed a ligand binding model in which Pocket 3 accepts N-acetyl-Pro1Ala2Pro3Gly4Phe5-amide, a virtual penta-peptide of a type 2 motif sequence derived from PLSCR3, by using the docking simulation program AutoDock Vina [33]. The calculated lowest energy model (−7.8 kcal/mol; Supplementary file of DockModel_Scr3_ABM-2 in PDB format) was analyzed for protein-ligand interactions by LIGPLOT [34] and NCONT [35]. A schematic diagram is shown in Figure 4, and interactions are listed in Table 3. In this docking model, carbon atoms of Pro1, Ala2 and Phe5 of the ligand interact with side chains of L48, A51, L52, S53, F85, W89, I92, Q96 and F148. The carbon atom from the methyl moiety of the acetyl group also interacts hydrophobically with F99 and G108. On the other hand, hydrogen bonds are predicted to be formed between oxygen atoms of peptide bonds (Pro1, Ala2 and Phe5) and oxygen atoms and a nitrogen atom of Pocket 3 residues in ALG-2 (S53, T93 and Q96). Moreover, a nitrogen atom of the C-terminal amide forms a hydrogen bond with an oxygen atom in the side chain of Gln96 (Table 3, not shown in Figure 4). As shown in Figure 5, interacting residues are from three segments in the ALG-2 primary structure: (i) α-helix 2 (exiting helix of EF1) and the following loop (L48, A51, L52, S53); (ii) α-helix 4 that is continuous from the exiting helix of EF2 and entering helix of EF3 (F85, W89, I92, T93, Q96 and F99) and EF3 loop, and (iii) the start of α-helix 7 (F148). As shown in Figure 6, the model peptide fits well into Pocket 3. While Pro3 and Phe5 of the peptide settle to the bottom by interacting with L52 (colored in yellow) and F148 (colored in light green), the linker segment, Pro3Gly4, loops out from the cavity.

Figure 3.

Stereoview of Pocket 3. Surfaces containing the newly designated Pocket 3, corresponding to the predicted binding sites of ID Nos. 2 and 4, are shown and colored according to a hydrophobicity scale (upper panel). Close-up views in stereo (parallel viewing method) are shown and half-transparent surfaces are merged with stick models (bottom panels) of residues involved in the formation of the predicted binding site. Elements are colored only for Pocket 3: carbon, green; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; sulfur, orange.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of interactions between ALG-2 and the model peptide generated by LIGPLOT. N-acetyl-ProAlaProGlyPhe-amide, a virtual type 2 motif penta-peptide ligand derived from PLSCR3, was subjected to docking simulation for binding to Pocket 3 by AutoDock Vina, and residues with interactions between a ligand and ALG-2 are schematically displayed by LIGPLOT. Amino acid residues are represented by one and three letter codes for ALG-2 (A) and ligand (L), respectively. Atoms of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen are indicated by small closed circles in black, red and blue, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by green broken lines. Hydrophobic contacts are indicated by quarter open circles (ALG-2) and small black closed circles (carbon atoms of ligand) with reddish prickles. Ace, acetyl group.

Table 3.

Hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds between a virtual N-acetyl-ProAlaProGlyPhe-amide peptide and ALG-2.

| Interacting atoms in peptide | Interacting atoms in ALG-2 | Distance (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic | |||

| ACE | C a | CE2F99 | 3.7 |

| CAG108 | 3.6 | ||

| Pro1 | CG | CBQ96 | 3.9 |

| CB | CGQ96 | 3.7 | |

| CG | CGQ96 | 3.9 | |

| CA | CD2F148 | 3.9 | |

| CB | CD2F148 | 3.5 | |

| CB | CE2F148 | 3.8 | |

| CB | CGF148 | 3.7 | |

| Ala2 | CA | CBS53 | 3.5 |

| CB | CBS53 | 3.5 | |

| Phe5 | CZ | CD1L48 | 3.8 |

| CE2 | CBA51 | 3.6 | |

| CD2 | CD2L52 | 3.8 | |

| CE2 | CD2L52 | 3.7 | |

| CZ | CD2L52 | 3.9 | |

| CE1 | CE1F85 | 3.8 | |

| CZ | CE1F85 | 3.5 | |

| CZ | CZF85 | 3.7 | |

| CD1 | CD1W89 | 3.8 | |

| CE1 | CAW89 | 3.8 | |

| CB | CG2I92 | 3.7 | |

| CD1 | CG2I92 | 3.6 | |

| CG | CG2I92 | 3.8 | |

| Hydrogen bonds | |||

| Pro1 | O | OGS53 | 3.1 |

| Ala2 | O | NE2Q96 | 3.1 |

| Phe5 | O | OG1T93 | 3.0 |

| NH2 | N | OE1Q96 | 3.0 |

Carbon atom from methyl moiety of acetyl group.

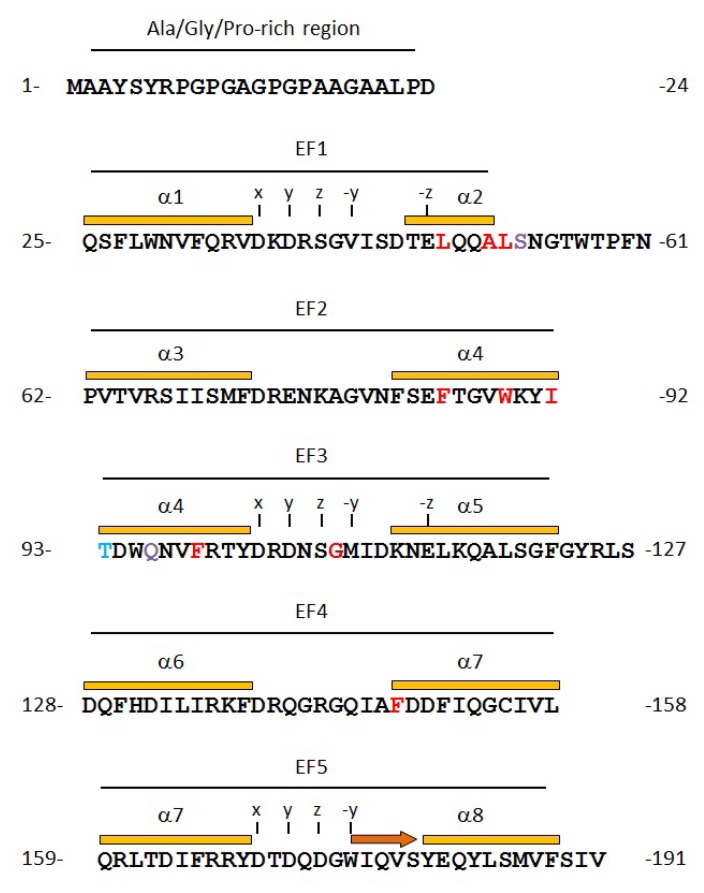

Figure 5.

Distributions of the predicted ligand-interacting residues in the primary structure of ALG-2. ALG-2 amino acid residues predicted to interact with the virtual peptide N-acetyl-ProAlaProGlyPhe-amide are colored in red, cyan and purple for hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds and both, respectively. Each helix-loop-helix structural motif of EF-hands is marked from EF1 to EF5. Eight α-helices (α1 to α8) and one β-sheet are indicated by orange bars and a dark orange arrow above the sequences. Calcium ions are coordinated with oxygen atoms at positions x, y, z, −y and −z from amino acid residues and with an oxygen atom at position −x from the neighboring water molecule.

Figure 6.

Docking simulation. (A) Residues forming Pocket 3 and its vicinity are shown by surface representation in gray except for F148 in light green and L52 in yellow. The type 2 motif peptide is represented by a stick model in which atoms of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen are shown in cyan, blue and red, respectively, in the upper panel. A side view of the structure shown in the upper panel obtained by rotating 60° around the indicated axis is presented in the lower panel; (B) The peptide shown in (A) upper panel is rotated 75° around the axis and represented in stereoview (parallel viewing method). Hydrophobic interactions between the type 2 motif peptide and ALG-2 are shown for F148 (carbon atoms, green) and L52 (carbon atoms, yellow). Broken lines indicate hydrophobic interactions with distances shorter than or equal to 3.9 Å (see Table 3 for details).

The crystal structure of ALG-2 in the Ca2+-bound form (PDB ID 2zn9) shows that Pocket 3 is largely covered with a crystallographic symmetry-related monomer (not the partner of dimer, Supplementary Figure S1). Inaccessibility of the ABS-2 peptide to Pocket 3 in the crystal might explain why we could not obtain the crystal structure of the complex between ALG-2 and the ABS-2 peptide. Masking of Pocket 3 by another ALG-2 molecule, however, may happen only in the crystal and in solution, if it happens at all, at a very high concentration of ALG-2. Pocket 3 should be opened to the ligand in the cell and in solution under experimentally controlled conditions.

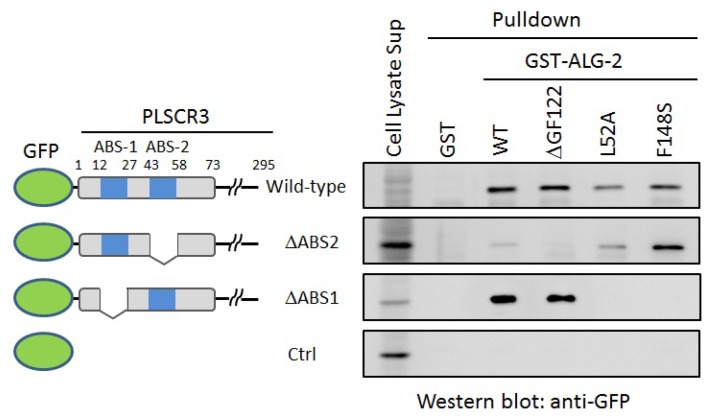

2.4. In Vitro Binding Assay

To investigate the possibility that Pocket 3 is a genuine binding site for type 2 motif as predicted, we performed in vitro binding assays using amino acid-substituted mutants of ALG-2. Since a high concentration of ALG-2 (~5 μM) tends to aggregate in the presence of Ca2+ [36] and hampers analyses of protein-ligand interaction. Addition of non-ionic detergent alleviates the problem of aggregation but limits the methods to be employed for interaction analyses. Here we employed the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pulldown method. Immobilization of the GST-fused ALG-2 proteins on glutathione Sepharose beads was thought to be effective to avoid the potential masking problem of Pocket 3 by neighboring ALG-2 molecule as described above. Among the predicted interacting residues of ALG-2, L52 and F148 were targeted for amino acid substitutions (L52, alanine; F148, serine) since they are located in the boundary of helices and loops and adverse effects on the secondary structures were presumed to be minimal (Figure 5). Supernatants of the lysates of cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused PLSCR3 of wild-type and mutants lacking either ABS-1 or ABS-2 were subjected to GST-pulldown assays in the presence of 100 μM CaCl2 and 0.1% Triton X-100, and proteins bound to the glutathione Sepharose beads were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-GFP antibody. As shown in Figure 7, while GFP-Scr3ΔABS1 (retaining type 2 motif) was not detected in the pulldown fractions of GST-ALG-2L52A and GST-ALG-2F148S, GFP-Scr3ΔABS2 (retaining type 1 motif) was detected in the case of these ALG-2 mutants. Retaining of the binding ability to type 1 motif suggests that structural adverse effects caused by amino acid substitutions of L52 and F148 are locally limited to Pocket 3 and, if any, its surroundings. In contrast, GST-ALG-2ΔGF122 showed opposite results: binding to GFP-Scr3ΔABS1 but not to GFP-Scr3ΔABS2. Unexpectedly, wild-type GST-ALG-2 showed a poorer binding ability to GFP-Scr3ΔABS2 than mutant ALG-2 proteins (2nd panel from the top). ABS-1 may have a weaker binding ability than ABS-2, but mutations of Pocket 3 might somehow favored ALG-2 with a stronger binding to ABS1, possibly by avoiding competition with endogenous type 2 motif-containing proteins including Sec31A. In other words, occupation of Pocket 3 might inhibit binding of type 1 motif-containing proteins to Pocket 1 and 2 in the same monomer molecule probably due to steric hindrance. No significant signals for GFP-Scr3 were detected in pulldown fractions of the wild-type and mutant GST-ALG-2 proteins in the presence of 5 mM EGTA, a Ca2+ chelator, (Supplementary Figure S2), indicating that mutations of L52 and F148 did not abrogate the Ca2+-dependency of interaction. In the second and third lowest energy models (−6.8 kcal/mol and −6.5 kcal/mol, respectively) obtained by the ligand binding simulation with AutoDock Vina, the peptide binds to a part of Pocket 2, and neither L52 nor F148 interacts with the model peptides (data not shown). Thus, the results strongly suggest that Pocket 3 is the most probable candidate for the type 2 motif-binding site and that the two types of ALG-2-binding motifs are accepted by different pockets in ALG-2.

Figure 7.

Effects of amino acid substitutions in Pocket 3 on the binding abilities to PLSCR3 by GST-ALG-2 pulldown assays. HEK293/ALG-2KD cells were transfected with expression vectors for GFP-fused PLSCR3 of wild-type, ABS2-deletion mutant (ΔABS2), ABS1-deletion mutant (ΔABS1) and unfused GFP used as a negative control (Ctrl). Supernatants of cell lysates were subjected to pulldown assays using GST-fused ALG-2 proteins of wild-type (WT), alternatively spliced isoform lacking Gly121Phe122 (ΔGF122), mutant of Leu52 to alanine substitution (L52A) and mutant of Phe148 to serine substitution (F148S) as well as unfused GST used as a negative control in the presence of 100 μM CaCl2. Proteins bound to the glutathione Sepharose beads (pulldown fractions) were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-GFP antibody. Protein samples corresponding to 1% of total cleared cell lysates (Cell Lysate Sup) and 20% of pulldown fractions (Pulldown) were loaded to each lane on 10% gels of SDS-PAGE.

2.5. Ca2+-Dependent Interaction

Previous studies on crystal structures of the Ca2+-bound form of ALG-2 revealed binding of Ca2+ to EF1, EF3 and EF5 [21,37], among which the structure of EF1 was found not to be changed by Ca2+ binding in a comparison of the 3D structures with the metal-free form [21]. On the other hand, comparison of the metal-free form and the Ca2+-bound form of ALG-2 revealed a difference in configuration of the side chain of R125 that is present in the loop connecting EF3 and EF4 and interacts with the ALIX peptide in Pocket 1. Since EF5 has an incomplete Ca2+-coordination at the −z position (water molecule oxygen atom instead of bidentate side chain oxygen atoms of glutamic acid), its binding affinity seems to be lower than affinities of the other two EF-hands [21]. Assuming that binding of Ca2+ to EF3 is the most critical step for ALG-2 to accept ligands, we proposed a Ca2+/EF3-induced R125 switch model to explain Ca2+-dependent interaction between ALG-2 and ALIX [21]. This model, however, is not applicable to explain the Ca2+-dependent binding of type 2 motif peptides, and it remains to be clarified how the signal of binding of Ca2+ to EF3 is transduced to Pocket 3. Interestingly, some residues predicted to interact with the virtual type 2 motif peptide are localized in α-helix 4 that forms a part of EF2 and EF3 (Table 3, Figure 5), suggesting that EF3 is somehow involved in the Ca2+-dependency for interaction with type 2 motif-containing proteins. Although attempts of co-crystallization of ALG-2 in the complex with the type 2 motif peptides of PLSCR3 and Sec31A have failed, the new finding of Pocket 3 as the most probable candidate of the type 2 motif-binding site provides us a new idea for designing a ligand and/or mutant ALG-2 to facilitate crystallization of the complex for X-ray crystallography, and a definite solution to the Ca2+-dependent type 2 motif-binding mechanism will be obtained in the future.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Prediction of Potential Binding Sites and Docking Simulation

A program of binding site predictor MetaPocket 2.0 [23] was run online [38]. A molecular visualization tool, PyMol [39], was used for structure representations and measurement of distances between atoms. For surface representation of hydrophobicity by PyMol, rTools 0.7.2 [40] was down-loaded and protscale was selected from Plugin. A 3D-structural model of the virtual peptide of N-acetyl-ProAlaProGlyPhe-amide containing type 2 motif was first constructed with COOT [41] and used for ligand docking simulation program AutoDock Vina [33,42]. The program was run by fixing the grids so that they covered entire Pocket 3 and also a part of Pocket 2, which is located at the back side of Pocket 3. Protein-ligand interactions were analyzed using the program LIGPLOT v.4.5.3 [34,43], and selected by NCONT in the CCP4 suite [35].

3.2. Expression and Purification of Mutant ALG-2 Proteins

Mutations of nucleotides for amino acid substitutions in ALG-2 were performed by the PCR-based mutagenesis method using pairs of specific primers (L52A substitution: forward: 5′-GCTTCAGCAAGCTGCCTCCAACGGCACGTG-3′; reverse: 5′-CACGTGCCGTTGGAGGCAGC TTGCTGAAGC-3′; F148S substitution: forward: 5′-GGGCAGATCGCCAGCGACGACTTCATC CAG-3′; reverse: 5′-TGGATGAAGTCGTCGCTGGCGATCTGCCC-3′), an expression plasmid of GST-fused human ALG-2 (pGEX-4T-3/hALG-2) [12] as a template and KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) essentially according to the instruction manual of a QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA 95051, USA). After being digested with DpnI (Takara Bio Inc, Osaka, Japan), PCR products were used for transformation of Escherichia coli Top10. Isolated plasmid DNAs were subjected to DNA sequencing. After confirming nucleotide substitutions at the targeted sites but no changes in the rest of the ALG-2 cDNA sequence, Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with the plasmids, and mutant ALG-2 proteins were expressed and affinity-purified using glutathione Sepharose beads as described elsewhere. Eluted ALG-2 proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 μM EDTA, 10 μM EGTA, and 100 mM NaCl and re-adsorbed to Sepharose beads.

3.3. GST-Pulldown Assays

An ALG-2 knocked down cell line (designated HEK293/ALG-2KD) [32] that was established previously by the RNA interference method was used to minimize effects of competition on target binding between endogenous ALG-2 present in the cells and GST-ALG-2 immobilized on Sepharose beads. HEK293/ALG-2KD cells were transfected with expression plasmids for GFP-fusion proteins of wild-type and deletion mutants of PLSCR3 by the conventional calcium phosphate precipitation method. One day after transfection, harvested cells were lysed with buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors), and supernatants obtained after centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C were subjected to GST-pulldown assays essentially as described previously after addition of CaCl2 to 100 μM [10,12]. Briefly, Sepharose beads immobilizing GST-ALG-2 proteins were incubated with cleared cell lysates at 4 °C overnight. After Sepharose beads had been recovered by low-speed centrifugation (700 g) for 1 min and washed three times with buffer A containing 100 μM CaCl2, proteins bound to the beads were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Proteins transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) were probed with an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (clone B-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Signals of Western blotting were detected by the chemiluminescence method using Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., IL, USA) and analyzed with LAS-3000mini (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, a type 2 motif-binding site in ALG-2 was predicted by using a binding-site prediction program. Docking simulation enabled creation of amino acid substitution mutants that were examined by in vitro binding experiments. These mutants had lost type 2 motif-binding ability but retained type 1 motif-binding ability, suggesting the presence of motif-specific ligand-binding sites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Atsuo Suzuki, Nagoya University Graduate School of Engineering, for valuable suggestions on binding site simulation. This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) to M. M. (Project No. 23380056).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1, S2 and Supplementary files in PDB formats are available at IJMS online.

References

- 1.Maki M., Narayana S.V., Hitomi K. A growing family of the Ca2+-binding proteins with five EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 1997;328:718–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maki M., Kitaura Y., Satoh H., Ohkouchi S., Shibata H. Structures, functions and molecular evolution of the penta-EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1600:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maki M., Maemoto Y., Osako Y., Shibata H. Evolutionary and physical linkage between calpains and penta-EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins. FEBS J. 2012;279:1414–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maki M., Suzuki H., Shibata H. Structure and function of ALG-2, a penta-EF-hand calcium-dependent adaptor protein. Sci. China Life Sci. 2011;54:770–779. doi: 10.1007/s11427-011-4204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vito P., Lacana E., D’Adamio L. Interfering with apoptosis: Ca2+-binding protein ALG-2 and Alzheimer’s disease gene ALG-3. Science. 1996;271:521–525. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Missotten M., Nichols A., Rieger K., Sadoul R. Alix, a novel mouse protein undergoing calcium-dependent interaction with the apoptosis-linked-gene 2 (ALG-2) protein. Cell. Death Differ. 1999;6:124–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vito P., Pellegrini L., Guiet C., D’Adamio L. Cloning of AIP1, a novel protein that associates with the apoptosis-linked gene ALG-2 in a Ca2+-dependent reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1533–1540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satoh H., Nakano Y., Shibata H., Maki M. The penta-EF-hand domain of ALG-2 interacts with amino-terminal domains of both annexin VII and annexin XI in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1600:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoh H., Shibata H., Nakano Y., Kitaura Y., Maki M. ALG-2 interacts with the amino-terminal domain of annexin XI in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:1166–1172. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katoh K., Suzuki H., Terasawa Y., Mizuno T., Yasuda J., Shibata H., Maki M. The penta-EF-hand protein ALG-2 interacts directly with the ESCRT-I component TSG101, and Ca2+-dependently co-localizes to aberrant endosomes with dominant-negative AAA ATPase SKD1/Vps4B. Biochem. J. 2005;391:677–685. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamasaki A., Tani K., Yamamoto A., Kitamura N., Komada M. The Ca2+-binding protein ALG-2 is recruited to endoplasmic reticulum exit sites by Sec31A and stabilizes the localization of Sec31A. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:4876–4887. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibata H., Suzuki H., Yoshida H., Maki M. ALG-2 directly binds Sec31A and localizes at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;353:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montaville P., Dai Y., Cheung C.Y., Giller K., Becker S., Michalak M., Webb S.E., Miller A.L., Krebs J. Nuclear translocation of the calcium-binding protein ALG-2 induced by the RNA-binding protein RBM22. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draeby I., Woods Y.L., la Cour J.M., Mollerup J., Bourdon J.C., Berchtold M.W. The calcium binding protein ALG-2 binds and stabilizes Scotin, a p53-inducible gene product localized at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;467:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibata H., Suzuki H., Kakiuchi T., Inuzuka T., Yoshida H., Mizuno T., Maki M. Identification of Alix-type and Non-Alix-type ALG-2-binding sites in human phospholipid scramblase 3: Differential binding to an alternatively spliced isoform and amino acid-substituted mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9623–9632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osugi K., Suzuki H., Nomura T., Ariumi Y., Shibata H., Maki M. Identification of the P-body component PATL1 as a novel ALG-2-interacting protein by in silico and Far-Western screening of proline-rich proteins. J. Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang I.S., Jung Y.S., Kim E. Interaction of ALG-2 with ASK1 influences ASK1 localization and subsequent JNK activation. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C., Sytkowski A.J. Apoptosis-linked gene-2 connects the Raf-1 and ASK1 signalings. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2005;333:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergarajauregui S., Martina J.A., Puertollano R. Identification of the penta-EF-hand protein ALG-2 as a Ca2+-dependent interactor of mucolipin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:36357–36366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata H., Inuzuka T., Yoshida H., Sugiura H., Wada I., Maki M. The ALG-2 binding site in Sec31A influences the retention kinetics of Sec31A at the endoplasmic reticulum exit sites as revealed by live-cell time-lapse imaging. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010;74:1819–1826. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki H., Kawasaki M., Inuzuka T., Okumura M., Kakiuchi T., Shibata H., Wakatsuki S., Maki M. Structural basis for Ca2+-dependent formation of ALG-2/Alix peptide complex: Ca2+/EF3-driven arginine switch mechanism. Structure. 2008;16:1562–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikura M., Ames J.B. Genetic polymorphism and protein conformational plasticity in the calmodulin superfamily: Two ways to promote multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1159–1164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508640103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z., Li Y., Lin B., Schroeder M., Huang B. Identification of cavities on protein surface using multiple computational approaches for drug binding site prediction. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang B., Schroeder M. LIGSITEcsc: Predicting ligand binding sites using the Connolly surface and degree of conservation. BMC Struct. Biol. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brady G.P., Jr, Stouten P.F. Fast prediction and visualization of protein binding pockets with PASS. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2000;14:383–401. doi: 10.1023/a:1008124202956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurie A.T., Jackson R.M. Q-SiteFinder: An energy-based method for the prediction of protein-ligand binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1908–1916. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski R.A. SURFNET: A program for visualizing molecular surfaces, cavities, and intermolecular interactions. J. Mol. Graph. 1995;13:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Guilloux V., Schmidtke P., Tuffery P. Fpocket: An open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawabata T. Detection of multiscale pockets on protein surfaces using mathematical morphology. Proteins. 2010;78:1195–1211. doi: 10.1002/prot.22639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capra J.A., Laskowski R.A., Thornton J.M., Singh M., Funkhouser T.A. Predicting protein ligand binding sites by combining evolutionary sequence conservation and 3D structure. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J., Zhou Y., Tanaka I., Yao M. Roll: A new algorithm for the detection of protein pockets and cavities with a rolling probe sphere. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:46–52. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okumura M., Ichioka F., Kobayashi R., Suzuki H., Yoshida H., Shibata H., Maki M. Penta-EF-hand protein ALG-2 functions as a Ca2+-dependent adaptor that bridges Alix and TSG101. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;386:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace A.C., Laskowski R.A., Thornton J.M. LIGPLOT: A program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collaborative Computational Project. Number 4. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maki M., Yamaguchi K, Kitaura Y, Satoh H, Hitomi K. Calcium-induced exposure of a hydrophobic surface of mouse ALG-2, which is a member of the penta-EF-hand protein family. J. Biochem. 1998;124:1170–1177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jia J., Tarabykina S., Hansen C., Berchtold M., Cygler M. Structure of apoptosis-linked protein ALG-2: Insights into Ca2+-induced changes in penta-EF-hand proteins. Structure. 2001;9:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MetaPocket 2.0. [accessed on 24 February 2012]. Available online: http://projects.biotec.tu-dresden.de/metapocket.

- 39.PyMol. [accessed on 26 January 2012]. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/

- 40.Kristian R. PyMOL plugins. 2007. [accessed on 27 February 2012]. Available online: http://www.rubor.de/pymol_extensions_en.html.

- 41.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AutoDock Vina. [accessed on 3 March 2012]. Available online: http://autodock.scripps.edu/

- 43.LIGPLOT. [accessed on 3 March 2012]. Available online: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LIGPLOT/