α-Functionalized phosphonic acid derivatives are of biomedical interest, as they have been found to display inhibitory activity towards several important groups of enzymes, including renin, thrombin, ESPS synthase, HIV protease, and various classes of protein tyrosine kinases and phosphatases. The pharmaceutical potential of these compounds has stimulated the development of methodology for their preparation, particularly in enantiomerically enriched forms. Much of this effort has been directed toward the synthesis of α-hydroxy phosphonates, including enzymatic[1, 3,4] and chemical methods[2,5–9]. The available methods are suitable primarily for the synthesis of secondary α-hydroxy phosphonates. A notable exception is the recent report of Samantha and Zhao, in which the use of proline derivatives to promote the aldol reaction of ketones and acylphosphonates yielded tertiary α-hydroxy phosphonates.[10] In this and related aldol reactions, the secondary amine, through covalent attachment, forms a chiral enamine that participates in a diastereoselective addition reaction with the carbonyl component. We report herein the first examples of tertiary α-hydroxy phosphonate ester synthesis promoted by hydrogen-bond catalysis. The reactions proceed in good yield and excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity.

Over the past decade hydrogen-bond catalysis has mushroomed into a powerful strategy for asymmetric synthesis.[11] Of the successful applications of this paradigm in the promotion of 1,2-additions, most involve the use of an imine as the electrophilic partner.[12] Among hydrogen-bond-promoted additions to carbonyl compounds, the reported examples primarily involve aldehydes.[13, 14] We reasoned that acid chloride equivalents, such as acyl phosphonates (or perhaps even acyl cyanides), could function as effective electrophiles in such reactions because the hydroxy phosphonate product is known to be thermodynamically stable. The reaction of a β-substituted enol ether with acetyl dimethyl phosphonate would give a product having two chiral centers, including a tertiary α-hydroxy phosphonate, produced by a method that complements the asymmetric hydrophosphonylation reaction [Eq. (1)].[8] The latter process has only been reported for aldehydes.

|

(1) |

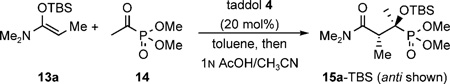

A variety of chiral organic molecules were evaluated as hydrogen-bond donor catalysts for the above reaction, including amino alcohols, diols, thioureas, and cinchona alkaloids (Figure 1).[15] The high reactivity profile of N,O-ketene acetals (e.g., 13) and their prior success in the aldol reaction prompted us to use this nucleophile for the present study (Table 1). This survey showed that many common hydrogen-bond donors, without additional structural optimization, accelerated the Mukaiyama aldol reaction between N,O-ketene acetal 13 and acetyl phosphonate 14. Indeed, most catalysts provided an improved diastereoselectivity over the uncatalyzed reaction, although they varied widely in their ability to induce enantiselectivity. Whereas the indanol-based ligand 1 gave low enantioselectivity, Trost’s ligand (2) and proline-derived amino alcohol 8 gave promising selectivities of 20% and 34%ee, respectively. The best diastereo- and enantioselectivities were obtained with the taddol (α,α,α′,α′-tetraaryl-1,3-dioxolane-4,5-dimethanol) family of diols, such as 3 and 4. Even though 3 provided a slightly better selectivity, the more easily accessible and commercially available taddol 4 was selected for additional studies.

Figure 1.

Hydrogen-bond donor catalysts for asymmetric aldol reaction with acetyl phosphonate.

Table 1.

Various hydrogen-bond donors as catalysts for the diastereoselective and enantioselective Mukaiyama aldol reaction.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | t [h] | Conv. [%] | d.r. (anti/syn) | ee [%] |

| 1 | – | 7.5 | 63 | 10 | – |

| 2 | 1 | 10 | 87 | 23 | 9 |

| 3 | 2 | 7.5 | 79 | 20.5 | 20 |

| 4 | 3 | 10 | 92 | 33 | 90 |

| 5 | 4 | 10 | 92 | 30 | 90 |

| 6 | 5 | 10 | 86 | 14.5 | 0 |

| 7 | 6 | 7.5 | 75 | 12.7 | 0 |

| 8 | 7 | 7.5 | 51 | 25 | 0 |

| 9 | 8 | 10 | 67 | 25 | 34 |

| 10 | 9 | 7.5 | 58 | 13.5 | 0 |

| 11 | 10 | 16 | 85 | 23 | 0 |

| 12 | d-fructose | 16 | 92 | 12.5 | 0 |

| 13 | d-glucose | 16 | 94 | 12.5 | 0 |

| 14 | 11 | 7.5 | 44 | n.d. | 5 |

| 15 | 12 | 7.5 | 43 | n.d. | 0 |

Reactions were performed in toluene at −40 °C and 0.3 m concentration.

n.d. = not determined.

The result obtained with taddol 4 was further optimized by varying the reaction parameters (Table 2). The reaction was quite rapid at room temperature, but afforded the product in low diastereo- and enantioselectivity, and in modest yield (Table 2, entry 1). A longer reaction time did not significantly improve the yield (Table 2, entry 2). Careful examination of the crude reaction samples, from the room temperature reactions, by NMR analysis revealed the presence of silyl enol ether 16 and propanamide 17, arising from the transfer of the silyl group between the reactants. Carrying out the reaction at 0°C not only decreased the proportion of the side products but also increased the diastereo- and enantioselectivity of the product (Table 2, entries 3 and 4). Lowering the temperature to −80 °C, gave rise to a more useful reaction, having a 33:1 diastereomeric ratio and 94% ee for the major isomer (Table 2, entry 5). A longer reaction time improved the yield (Table 2, entry 6). Diastereo- and entioselectivities eroded as the catalyst loading was lowered, although a useful reaction was obtained at 10 mol% catalyst loading (Table 2, entries 7–9). The reaction was also carried out using the corresponding diethyl and diisopropyl acetyl phosphonates, but both gave inferior results.[16] Optimum results were obtained when the reaction was carried out at −80 °C with 20 mol% of the catalyst and using the acyl phosphonate as the limiting reagent (Table 2, entry 10). The above reaction represents, to our knowledge, not only the first hydrogen-bond-catalyzed enantioselective aldol reaction of an acyl phosphonate, but also one in which two chiral centers are set, one of which is a tertiary α-hydroxy phosphonate ester.

Table 2.

Optimization of the reaction conditions.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst [mol%] | T [°C] | t [h] | Yield [%] | d.r. (anti/syn) | ee [%] |

| 1[a] | 20 | 22 | 0.5 | 48 | 5.8 | 67 |

| 2[a] | 20 | 22 | 1.5 | 55 | 4.4 | 68 |

| 3 | 20 | 0 | 12 | 47 | 14 | 87 |

| 4 | 20 | −40 | 12 | 68 | 27 | 90 |

| 5 | 20 | −80 | 22 | 58 | 33 | 94 |

| 6 | 20 | −80 | 48 | 73 | 33 | 94 |

| 7 | 10 | −80 | 48 | 74 | 29 | 90 |

| 8 | 5 | −80 | 48 | 54 | 26 | 87 |

| 9 | 2 | −80 | 48 | 39 | 30 | 84 |

| 10[b] | 20 | −80 | 48 | 89 | 33 | 95 |

All reactions were performed by using 1 equivalent of N,O-ketene acetal and 1.5 equivalent of acyl phosphonate. The limiting reagent was at 0.3 m concentration.

Silyl enol ether 16 was present in the crude product before quenching.

Acyl phosphonate 14 was the limiting reagent.

To assess the utility of the hydrogen-bond-promoted acyl phosphonate aldol reaction, we examined the reaction of N,O-ketene acetals having various subtituents (Table 3). The reactions were quenched with an HF solution to remove the tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) group. The reactants were selected to illustrate the scope of the reaction as well as the ability to generate aldol adducts substituted with useful functional groups. Alkyl-substituted ketene acetals generally gave the corresponding products in high diastereo- and enantioselectivities (Table 3, entries 1–3). Whereas a sluggish reaction was observed with the isopropyl substituted ketene acetal, moving the bulky group one carbon atom away provided a useful reaction (Table 3, entry 4). The reaction was also effective with heteroatom-substituted N,O-ketene acetals. Both methoxy- and phenoxy-substituted ketene acetals underwent the aldol reaction smoothly to provide the corresponding products with high diastereo- and enantioselectivities (Table 3, entries 5 and 6). The p-methoxyphenoxy-substituted (PMP-O) ketene acetal was also investigated as removal of the PMP group in the product would provide α,β-dihydroxy phosphonate esters. The required enol ether was used without purification and provided the aldol product with excellent selectivity (>99:1 d.r., 99%ee; Table 3, entry 7). The anti stereochemistry assigned to the major diastereomer was confirmed by the X-ray crystallographic analysis of the product 15g (Figure 2). As an additional demonstration of this methodology, both thioether- and chloro-substituted ketene acetals were effective reactants in the taddol catalyzed phosphonate aldol reaction, providing the expected products as essentially single diastereomers with excellent enantioselectivities (Table 3, entries 8 and 9). Interestingly, even lactam-derived enol ether 18 reacted well with acetyl phosphonate to afford the aldol product with near complete diastereoselectivity (tentatively assigned syn), albeit a lower with ee value [Eq. (2)].

|

(2) |

Table 3.

Scope of hydrogen-bond-promoted acetyl phosphonate aldol reaction.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Product | Yield [%] | d.r. (anti/syn) | ee [%] |

| 1 | Me | 15 a | 73 | 97:3 | 95 |

| 2 | Et | 15 b | 51 | 99:1 | 89 |

| 3 | Bn | 15 c | 66 | 99:1 | 91 |

| 4 | iBu | 15 d | 52 | 99:1 | 96 |

| 5 | OMe | 15 e | 61 | 99:1 | 95 |

| 6 | OPh | 15 f | 82 | 99:1 | 99 |

| 7 | OPMP | 15 g | 81 | 99:1 | 99 |

| 8 | SMe | 15 h | 52 | 99:1 | 98 |

| 9 | Cl | 15 i | 77 | 99:1 | 97 |

All reaction were performed in toluene at 0.3 m acyl phosphonate and 1.5 equivalent of ketene acetal.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of phosphonate aldol product 15g.[18]

The reaction of N,O-ketene acetals with other classes of reactive electrophiles was examined briefly to determine the generality of the above Mukaiyama aldol reaction. Of the electrophiles considered, acyl cyanides appeared to be particularly interesting, since their products would be silylated cyanohydrins of ketones, which are versatile synthetic intermediates. Thus the reaction of N,O-ketene acetal 13a with acetyl cyanide (20) under the standard reaction conditions provided the addition product in 78% yield, as 1:1 mixtures of diastereomers, with good to excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 1). The corresponding reaction of 13f proceeded in better selectivity, with the major diastereomer being formed in 90%ee. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports on enantioselective aldol reactions of acyl cyanides.[17]

Scheme 1.

Mukaiyama aldol reactions with pyruvonitrile.

In conclusion, we have described the first examples of hydrogen-bond-promoted enantioselective Mukaiyama aldol reactions with acyl phosphonates. These reactions are catalyzed by the simple, commercially available taddol 4. This mild and general method gives α-hydroxy phosphonate products with two chiral centers, one tertiary and one quaternary, formed with high diastereo- and enantioselection. The analogous enantioselective aldol reaction of acetyl cyanide can also be catalyzed through hydrogen-bonding interactions and gives quaternary silylated cyanohydrin products, formally the products of cyanosilylation of ketones.

Experimental Section

General procedure for the aldol reactions in Table 3: A flame-dried test tube capped with a septum was loaded with 20 mg taddol (0.031 mmol, 0.2 equiv), purged with argon, and maintained under a positive argon pressure. The vessel was charged with dry toluene (0.5 mL) and then placed in a −78°C bath. After 5 min, acyl phosphonate (20 µL, 0.153 mmol, 1 equiv) and the N,O-ketene acetal (60 µL, 0.23 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were added sequentially. The tube was then placed in a −80°C bath, and after 48 h the reaction was quenched with 0.3 mL of 5% HF/CH3CN. Progress of the TBS removal was monitored by TLC. After complete removal (2–5 h), the reaction mixture was diluted with methylene chloride and then washed successively with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution and brine. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated. Purification of the residue by using silica gel chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc 1:1) provided the product.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (USA). We thank Kyowa Hakko Co., Ltd. (Japan) for a sabbatical fellowship to K.H., and Prof. Dr. Chong Zheng (Northern Illinois University) for the crystal structure of 15g.

References

- 1.Review on enzymatic methods: Kafarski P, Lecjzak B. J. Mol. Catal. B. 2004;29:99–104.

- 2.Reviews on chemical methods: Wiemer DF. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16609–16644. Gröger H, Hammer B. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;6:943–948.

- 3.Kinetic resolution using enzymes: Li YF. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:109–120. Khushi T, O’Toole KJ, Sime JT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2375–2378. Drescher M, Li YF, Hammerschmidt F. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:4933–4946. Drescher M, Hammerschmidt F, Kahling H. Synthesis. 1995:1267–1272. Wuggenig F, Hammerschmidt F. Monatsh. Chem. 1998;129:423–436.

- 4.Examples of asymmetric reduction using enzymes: Maly A, Lejczak B, Kafarski P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:1019–1024. and references therein.

- 5.Reduction of keto phosphonates: Gajda T. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1965–1972. Meier C, Laux WHG. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:89–94. Nesterov V, Kolodyazhnyi OI. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2005;75:1161–1162.

- 6.Chemical methods for asymmetric oxidation of benzyl phosphonates: Pogatchnik DM, Wiemer DF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3495–3498. Cermak DM, Du Y, Wiemer DF. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:388–393. Skropeta D, Schmidt RR. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:265–723.

- 7.Diastereoselective phosphono-aldol reaction: Yokomatsu T, Yamamgishi T, Shibuya S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:1401–1404. Wróblewski AE, Balcerzak KB. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:427–431.

- 8.Enantioselective methods: Arai T, Bougauchi M, Sasai H, Shibasaki M. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:2926–2927. doi: 10.1021/jo960180o. Rowe BJ, Spilling CD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:1701–1708. Mandal T, Samantha S, Zhao CG. Org. Lett. 2007;9:943–945. doi: 10.1021/ol070209i.

- 9.Racemic addition of allyl silane to acetyl phosphonate: Kim DY, Wiemer DF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2803–2805.

- 10.Samantha S, Zhao CG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7442–7443. doi: 10.1021/ja062091r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Recent reviews on enantioselective reactions catalyzed by hydrogen-bond donors: McGilvra JD, Gondi VB, Rawal VH. In: Enantioselective organocatalysis. Dalko PI, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2007. pp. 189–254. Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5713–5743. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r. Yu X, Wang W. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:516–532. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700415. Takemoto Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:4299–4306. doi: 10.1039/b511216h.

- 12.For examples of hydrogen-bond-catalyzed asymmetric reactions of imines, see: Sigman MS, Vachal P, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:1336–1338. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000403)39:7<1279::aid-anie1279>3.0.co;2-u. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2000, 39, 1279–1281. Wenzel AG, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12964–12965. doi: 10.1021/ja028353g. Akiyama T, Itoh J, Yokota K, Fuchibe K. Angew. Chem. 2004;116:1592–1594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353240. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2004, 43, 1566–1568. Nugent BM, Yoder RA, Johnston JN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3418–3419. doi: 10.1021/ja031906i. Uraguchi D, Terada M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5356–5357. doi: 10.1021/ja0491533. Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10558–10559. doi: 10.1021/ja046259p. Wilt JC, Pink M, Johnston JN. Chem. Commun. 2008:4177–4179. doi: 10.1039/b808393b.

- 13.For selected examples of hydrogen-bond-catalyzed asymmetric reactions of carbonyl electrophiles, see: Schuster T, Bauch M, Düerner G, Göebel MW. Org. Lett. 2000;2:179–181. doi: 10.1021/ol991276i. McDougal NT, Schaus SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12094–12095. doi: 10.1021/ja037705w. Hoashi Y, Okino T, Takemoto Y. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:4100–4103. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500459. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2005, 44, 4032–4035. Rajaram S, Sigman MS. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5473–5475. doi: 10.1021/ol052300x. Tonoi T, Mikami K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:6355–6358. Rueping M, Ieawsuwan W, Antonchick AP, Nachtsheim BJ. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:2143–2146. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604809. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2007, 46, 2097–2100. Nakashima D, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9626–9627. doi: 10.1021/ja062508t. Terada M, Soga K, Momiyama N. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4190–4193. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800232. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2008, 47, 4122–4125.

- 14.Prior work from this lab on hydrogen-bond-catalyzed asymmetric reactions of carbonyl electrophiles: Huang Y, Unni AK, Thadani AN, Rawal VH. Nature. 2003;424:146. doi: 10.1038/424146a. Thadani AN, Stankovic AR, Rawal VH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5846–5850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308545101. Unni AK, Takenaka N, Yamamoto H, Rawal VH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1336–1337. doi: 10.1021/ja044076x. Gondi VB, Gravel M, Rawal VH. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5657–5660. doi: 10.1021/ol052301p. McGilvra JD, Unni AK, Modi K, Rawal VH. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:6276–6279. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601638. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2006, 45, 6130–6133.

- 15.Movassaghi M, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2002;298:1904–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.1076547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The results with diethyl and diisopropyl acetylphosphonates are provided in the Supporting Information. For higher alkyl-substituted ketophosphonates, the silyl group transfer pathway (cf. 16 and 17) dominated, and benzoyl phosphonate gave lower selectivity.

- 17.Lewis acid catalyzed racemic reactions: Kraus GA, Shimagaki M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1171–1174. Diastereoselective reactions: Reetz MT, Kesseler K, Jung A. Angew. Chem. 1985;97:989–990. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.1985, 24, 989–991.

- 18.CCDC 713147 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 15g. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/datarequest/cif.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.