Abstract

Objective

To determine participation in polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) in sub-Saharan Africa among users and non-users of routine immunization services and among users who were compliant or non-compliant with the routine oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) immunization schedule.

Methods

Data were obtained from household-based surveys in non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries. Routine immunization service users were children (aged < 5 years) who had ever had a health card containing their vaccination history; non-users were children who had never had a health card. Users were considered compliant with the OPV routine immunization schedule if, by the SIA date, their health card reflected receipt of required OPV doses. Logistic regression measured associations between SIA participation and use of both routine immunization services and compliance with routine OPV among users.

Findings

Data from 21 SIAs conducted between 1999 and 2010 in 15 different countries met inclusion criteria. Overall SIA participation ranged from 70.2% to 96.1%. It was consistently lower among infants than among children aged 1–4 years. In adjusted analyses, participation among routine immunization services users was > 85% in 12 SIAs but non-user participation was > 85% in only 5 SIAs. In 18 SIAs, participation was greater among users (P < 0.01 in 16, 0.05 in 1 and < 0.10 in 1) than non-users. In 14 SIAs, adjusted analyses revealed lower participation among non-compliant users than among compliant users (P < 0.01 in 10, < 0.05 in 2 and < 0.10 in 2).

Conclusion

Large percentages of children participated in SIAs. Prior use of routine immunization services and compliance with the routine OPV schedule showed a strong positive association with SIA participation.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer la participation aux campagnes de supplémentation vaccinale en Afrique subsaharienne parmi les utilisateurs et les non-utilisateurs des services de vaccination de routine et parmi les utilisateurs conformes ou non-conformes au protocole de vaccination antipoliomyélitique orale.

Méthodes

Les données ont été obtenues à partir d'enquêtes de ménages conduites dans des pays non-polio-endémiques d'Afrique subsaharienne. Les utilisateurs des services de vaccination de routine étaient des enfants (âgés de moins de 5 ans) ayant possédé un jour un carnet de santé contenant leur historique vaccinal; les non-utilisateurs étaient des enfants n’ayant jamais possédé de carnet de santé. Les utilisateurs ont été considérés comme conformes au protocole de vaccination antipoliomyélitique orale si, à la date de la campagne, leur carnet de santé reflétait l'administration des doses de vaccination antipoliomyélitique orale requises. Une régression logistique a mesuré les associations entre la participation à la campagne et tant le recours aux services de vaccination de routine que la conformité au protocole de vaccination antipoliomyélitique orale des utilisateurs.

Résultats

Les données provenant de 21 campagnes de supplémentation vaccinale menées entre 1999 et 2010 dans 14 pays différents ont satisfait les des critères d'inclusion. La participation globale aux campagnes variait de 70,2% à 96,1%. Elle était toujours plus faible chez les nourrissons que chez les enfants âgés de 1 à 4 ans. Dans les analyses ajustées, la participation parmi les utilisateurs des services de vaccination de routine était >85% dans 12 campagnes, mais la participation des non-utilisateurs était >85% pour seulement 5 campagnes. Dans 18 campagnes, la participation était plus élevée chez les utilisateurs (P <0,01 pour 16, <0,05 pour 1 et <0,10 pour 1) que chez les non-utilisateurs. Dans 14 campagnes, les analyses ajustées ont révélé une plus faible participation chez les utilisateurs non-conformes que chez les utilisateurs conformes (P <0,01 pour 10, <0,05 pour 2 et <0,10 pour 2).

Conclusion

Un pourcentage élevé d'enfants ont participé à des campagnes. Le recours antérieur aux services de vaccination de routine et la conformité au protocole de vaccination orale ont montré une forte corrélation positive avec la participation aux campagnes.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar la participación en las actividades suplementarias de inmunización (ASI) contra la poliomielitis en el África subsahariana entre los usuarios y no usuarios de los servicios de inmunización sistemática, así como entre los usuarios que se atuvieron o no al calendario de vacunación antipoliomielítica oral (OPV).

Métodos

Los datos se obtuvieron a través de encuestas de hogares en países del África subsahariana en los que la poliomielitis no es endémica. Los usuarios del servicio de inmunización sistemática fueron niños (con edades inferiores a cinco años) que disponían de una tarjeta sanitaria con sus antecedentes de vacunación; los no usuarios fueron niños que nunca habían tenido una tarjeta sanitaria. Se consideró que los usuarios cumplían con el calendario de vacunación OPV si, al iniciar la campaña, sus tarjetas sanitarias reflejaban que habían recibido las dosis OPV obligatorias. La regresión logística midió las relaciones existentes entre la participación en las ASI, el uso de ambos servicios de inmunización sistemática y la conformidad con la OPV sistemática entre los usuarios.

Resultados

Los datos de 21 ASI realizadas entre 1999 y 2010 en 15 países diferentes reunieron los criterios de inclusión. De manera global, la participación en las ASI fue de entre el 70,2% y el 96,1%, y fue sistemáticamente menor entre lactantes que entre niños con edades comprendidas entre uno y cuatro años. En los análisis ajustados, la participación entre los usuarios de los servicios de inmunización sistemática fue superior al 85% en 12 ASI, mientras que la participación de no usuarios fue superior al 85% en solo cinco ASI. En 18 de las actividades suplementarias de inmunización, la participación fue mayor entre usuarios (P < 0,01 en 16 de ellas, 0,05 en una y < 0,10 en una) que entre no usuarios. En 14 de las ASI, los análisis ajustados revelaron una participación menor entre usuarios que no se ajustaban al calendario de vacunación que entre aquellos que sí lo hacían (P < 0,01 en 10, < 0,05 en 2 y < 0,10 en 2).

Conclusión

Un porcentaje amplio de niños participaron en las actividades suplementarias de inmunización. El uso previo de servicios de inmunización sistemática y la conformidad con el calendario de OPV mostraron una relación positiva muy fuerte con la participación en las ASI.

ملخص

الغرض

تحديد المشاركة في أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA) في بلدان أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى بين مستخدمي وغير مستخدمي خدمات التمنيع الروتيني وبين المستخدمين الممتثلين أو غير الممتثلين لجدول التمنيع الروتيني باللقاح الفموي المضاد لفيروس السنجابية (OPV).

الطريقة

تم الحصول على البيانات من دراسات استقصائية منزلية في بلدان أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى التي لا يستوطنها شلل الأطفال. وكان مستخدمو خدمات التمنيع الروتيني هم الأطفال (أعمار ≥ 5 أعوام) الذين سبق لهم في أي وقت الحصول على بطاقات صحية تحتوي على تاريخ التمنيع الخاص بهم؛ وكان غير المستخدمين هم الأطفال الذين لم يسبق لهم في أي وقت الحصول على بطاقات صحية. واعتبر المستخدمون ممتثلين لجدول التمنيع الروتيني باللقاح الفموي المضاد لفيروس السنجابية (OPV) إذا أشارت البطاقات الصحية الخاصة بهم إلى الحصول على جرعات اللقاح الفموي المضاد لفيروس السنجابية المطلوبة وفق تاريخ أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA). وقاس الارتداد اللوجيستي العلاقات بين المشاركة في أنشطة التمنيع من شلل الأطفال واستخدام كل من خدمات التمنيع الروتيني والامتثال للتمنيع الروتيني باللقاح الفموي المضاد لفيروس السنجابية بين المستخدمين.

النتائج

لبت البيانات المستقاة من 21 نشاطاً من أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA) فيما بين 1999 و2010 في 15 بلدًا مختلفًا معايير الإدراج. وتراوحت المشاركة الإجمالية في أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال من 70.2 % إلى 96.1 %. وكانت أكثر انخفاضاً على نحو متسق بين الرضع عنه بين الأطفال التي تتراوح أعمارهم من سنة إلى 4 سنوات. وفي التحليلات المعدلة، كانت المشاركة بين مستخدمي خدمات التمنيع الدوري ≥85 % في 12 نشاطاً من أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA)، وكانت مشاركة غير المستخدمين ≥85 % في 5 أنشطة فقط من أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA). وكانت المشاركة في 18 نشاطاً من أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA) أكبر بين المستخدمين عنها بين غير المستخدمين (الاحتمال ≥ 0.01 في 16، و0.05 في نشاط واحد، و0.10 ≥ في نشاط واحد). وأظهرت التحليلات المعدلة في 14 نشاطاً من أنشطة التمنيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA) انخفاض المشاركة بين المستخدمين غير الممتثلين عنها بين المستخدمين الممتثلين (الاحتمال ≥ 0.01 في 10 أنشطة، و≥ 0.05 في نشاطين، و< 0.10 في نشاطين).

الاستنتاج

شاركت نسب كبيرة من الأطفال في أنشطة التمتيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA). وأوضح الاستخدام السابق لخدمات التمنيع الروتيني والامتثال لجدول التمنيع الروتيني باللقاح الفموي المضاد لفيروس السنجابية ارتباطًا إيجابيًا قويًا بالمشاركة في أنشطة التمتيع التكميلية من شلل الأطفال (SIA).

摘要

目的

确定撒哈拉以南非洲常规免疫服务的使用者和非使用者以及符合或不符合常规口服脊髓灰质炎疫苗(OPV)免疫计划的使用者参与脊髓灰质炎强化免疫活动(SIA)的情况。

方法

数据取自在非脊髓灰质炎流行的撒哈拉以南非洲国家开展的以家庭为基础的调查。常规免疫服务使用者是曾有过包含其疫苗接种史的医疗卡的儿童(年龄小于5 岁),非使用者是指从未有过医疗卡的儿童。如果在强化免疫活动日期之前,使用者的医疗卡反映其接受所需的OPV剂量,则视为符合OPV常规免疫计划。逻辑回归测量使用者的SIA参与情况和使用常规免疫服务和符合常规OPV之间的关联。

结果

1999 年至2010 年期间,在14 个不同的国家进行的21 个SIA的数据符合纳入标准。整体SIA参与率范围为70.2%至96.1%。较之1-4 岁儿童,婴儿的参与率总是更低。经过调整分析,在12 个SIA中,常规免疫服务使用者的参与率> 85%,但仅在5 个SIA中非使用者参与率> 85%。在18 个SIA中,使用者(16 个P < 0.01,1 个0.05,1 个P < 0.10)比非使用者的参与率高。在14个SIA中,调整分析显示非符合使用者较之符合使用者(10 个P < 0.01,2 个P < 0.05,2 个P < 0.10)参与率更低。

结论

参与SIA的儿童的百分比很高。先验使用常规免疫服务和符合常规OPV计划显示出与SIA明显的正相关。

Резюме

Цель

Определить степень участия в мероприятиях по дополнительной иммунизации (МДИ) против полиомиелита в регионах Африки южнее Сахары среди пользователей и не пользователей услуг регулярной иммунизации, а также среди пользователей, которые соблюдали и не соблюдали график регулярной иммунизации пероральной вакциной против полиомиелита (ИПВ).

Методы

Данные были получены с помощью опросов семей в неэндемичных для полиомиелита странах Африки южнее Сахары. Пользователями услуг регулярной иммунизации считались дети (в возрасте < 5 лет), у которых уже имелись медицинские карты с историей вакцинации; не пользователями – дети, никогда не имевшие медицинских карт. Считалось, что пользователи соблюдали график иммунизации, если к моменту МДИ в их медицинских картах были записи, подтверждающие получение необходимых доз ИПВ. С помощью логистической регрессии была измерена связь между участием в МДИ, а также пользованием услугами регулярной иммунизации и соблюдением графика вакцинации ИПВ среди пользователей.

Результаты

Данные 21 МДИ, проведенных между 1999 и 2010 гг. в 14 различных странах соответствовали критерию включения. Общее значение участия в МДИ было в диапазоне от 70,2% до 96,1%. Для младенцев оно было стабильно ниже, чем для детей в возрасте 1-4 лет. Скорректированный анализ показал, что уровень участия среди пользователей услуг регулярной иммунизации был > 85% в 12 МДИ, но среди не пользователей он был > 85% лишь в 5 МДИ. Для 18 МДИ участие было больше среди пользователей (P < 0,01 для 16, 0,05 для 1 и < 0,10 для 1), чем среди не пользователей. Для 15 МДИ скорректированный анализ показал более низкий уровень участия среди пользователей, которые не соблюдали график, чем среди пользователей, которые соблюдали график (P < 0,01 для 8, < 0,05 для 5 и < 0,10 для 2).

Вывод

В МДИ участвовал большой процент детей. Предварительное пользование услугами регулярной иммунизации и соблюдение графика регулярной вакцинации ИПВ показало тесную прямую связь с участием в МДИ.

Introduction

Since the late 1980s, use of supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) has been a key strategy of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). SIAs are mass vaccination campaigns that aim to administer additional doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) to each child aged < 5 years, regardless of their vaccination history. In doing so, SIAs attempt to remedy the limited ability of routine immunization services to reach at-risk children with the number of OPV doses required to generate immunity.1,2 In many countries, SIAs have largely contributed to the 99% global reduction in the incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis observed since the 1988 launch of the GPEI.2–4

Despite the central role of SIAs in eradication efforts, setbacks in the GPEI have been attributed to low-quality SIAs.5 Target dates for eradication have repeatedly been pushed back and, at present, transmission of wild poliovirus remains endemic in Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan. Four countries where circulation of wild poliovirus had stopped (Angola, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan) have been labelled as having “re-established polio transmission” and several other countries previously considered to be “polio free” have reported cases of acute flaccid paralysis due to wild poliovirus strains originating from northern Nigeria.6,7 A wild poliovirus “importation belt” thus stretches from Senegal to the Horn of Africa. To achieve eradication, the 2010–2012 GPEI strategic plan sets strict targets of > 90% coverage for each SIA conducted in the importation belt. Even in such highly immunized populations, however, outbreaks may still occur if much lower coverage is achieved for particular subpopulations.8 In particular, the influence of SIAs on population-level immunity against polio may be lowered if children who do not access routine immunization services (and are thus less likely to be immune to polio and other vaccine-preventable diseases) also participate less frequently in SIAs.

Very limited data on patterns of SIA participation are available that consider past use of routine immunization services. In a study of the 1997 Madagascar SIA, Andrianarivelo and colleagues9 reported significantly increased SIA-associated immunity among children who had not used routine immunization services or had missed routine OPV doses. Currently collected data on SIA coverage do not include an assessment of the immunization history of children who were not vaccinated during SIAs. The effectiveness of polio SIAs at supplementing routine immunization services in non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries is thus not known. In this article, we test the hypothesis that children who did not use routine immunization services before an SIA were less likely to participate in that SIA, compared with children who were users of routine services. We also measured SIA participation among users of routine immunization services who were compliant with the routine OPV immunization schedule, compared with users who were non-compliant.

Methods

Data collection and study groups

We used three data sources: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs), Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICSs) and the 2010 Mobile Technology for Community Health (MoTeCH) survey (Appendix A, available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sh2813/appendix-02292012sh.pdf). The first two sources are nationally representative household-based surveys conducted, on average, every 3–6 years in several sub-Saharan countries. The MoTeCH survey is a household-based survey conducted among women residing in the Kassena-Nankana East and West districts in Ghana’s Upper East Region. In all surveys, data on participation in SIAs and use of routine immunization services were collected in a similar manner. Mothers were asked to provide vaccination information for their surviving children < 5 years old.10–12 They were first asked whether their child had ever had a health card. Health cards are small booklets, usually given to mothers or guardians at the time of delivery or during the first vaccination visit, in which health workers record receipt of various antigens recommended through the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Expanded Programme on Immunization. For children whose health card was available at the time of the survey, interviewers transcribed the date of each vaccination recorded in the card. Interviewers then asked mothers to specify types of undocumented vaccination, if any, these children received. For children whose health card was not available at the time of the survey or who had never had a health card, interviewers asked mothers to specify every vaccination these children received but vaccination dates were not requested.

Because vaccinations received during polio SIAs are not recorded in children’s health cards by health workers and volunteers, OPV doses documented in health cards represent doses obtained through routine immunization services. We thus used health-card data to measure children’s prior use of routine immunization services in two ways. First, we used ownership of a health card to distinguish children who had ever used routine immunization services (hereafter, “users”) from children who had never used routine immunization services (hereafter “non-users”). Second, among users, we distinguished children who were compliant with routine OPV immunization from children who were not compliant by examining the age at which each OPV dose was received. Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa use a standard schedule for OPV: the first OPV dose is administered at 6 weeks of age; the second, at 10 weeks; and the third, at 14 weeks. Thus, we classified children as compliant if, at the time of the SIA, their health card reflected receipt of each required OPV dose. For example, a child who was 20 weeks old at the time of an SIA and had the third OPV dose documented in their health card would be classified as compliant, whereas a child who was 11 weeks old at the time of an SIA and had only the first OPV dose documented in their health card would be classified as non-compliant.

In many of the MICSs and DHSs and in the MoTeCH survey, mothers are asked about their children’s participation in recent polio SIAs. In some surveys, mothers are asked only whether their children participated in any SIA in recent years. In other surveys, mothers are asked whether their children participated in a specific SIA. Surveys were included in this study only if they included assessment of participation in a specific SIA for which the date of implementation was available. We obtained dates of SIAs directly from the survey questionnaire or indirectly from the WHO calendar of SIAs (available at: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/en/globalsummary/siacalendar/padvancedsia.cfm) To limit recall bias, we further excluded SIA data if collection of survey data began > 12 months after an SIA. We also excluded subnational SIAs because it was impossible to determine which of the children included in survey data sets were targeted.

Data analysis

All analyses excluded children whose day of birth was unavailable or who were born after the SIA of interest was held. Analyses of SIA participation among compliant and non-compliant users excluded children whose health card was not reviewed by the interviewer, was incomplete or had an invalid sequence of receipt dates for routine OPV doses (e.g. the date of the second dose was more recent than the date of the third dose).

Primary analyses used logistic regression models to measure the associations between SIA participation and prior routine immunization use and between SIA participation and routine immunization compliance. Such models included SIA participation as the (dichotomous) dependent variable and controlled for child age and sex, mother age and education level and household characteristics (i.e. religion and ethnicity of the household head, wealth quintile and urban/rural residence). We also included a set of regional fixed effects. Standard errors were adjusted for the clustering of observations within enumeration areas and households. We report adjusted frequencies of SIA participation derived from the logistic regression models, by routine immunization service use and routine OPV immunization compliance. These frequencies were computed using the margin command in Stata, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, United States of America), after setting other covariates at their mean value.

We conducted two robustness tests of the logistic regression models used in our primary analyses. The first test re-estimated the models after inclusion of all children for whom the month but not day of birth was available. In this test, only children who were aged > 4 months at the time of the SIA and, thus, were supposed to have completed the routine OPV schedule were included. The second test re-estimated the models after reclassification of children who first used routine immunization services after the SIA of interest as non-users.

In a secondary investigation, we compared the organizational attributes, human resources and budgetary allocations for three SIAs conducted in Benin, to explore why some SIAs are more successful than others at reaching undervaccinated children. Benin was selected for this investigation because (i) it is the only country for which we had survey data on participation in 3 SIAs, (ii) SIA implementation records were available to the study team and (iii) SIA participation among non-users of routine services during SIAs in 2005 and 2006 was significantly less than that during an SIA in 2000 (61–64% in 2005–2006 versus 91% in 2000, see below).

Results

Characteristics of SIAs and children

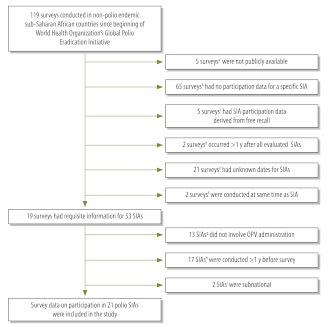

We reviewed data from 119 surveys conducted between 1988 and 2010. Data from 21 SIAs (Fig. 1) met inclusion criteria. These primarily included SIAs conducted in the wild poliovirus importation belt, as well as one in Lesotho and two in Namibia. One SIA was conducted in 1999, three in 2000, four in 2004, nine in 2005, three in 2006 and one in 2010.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of data set selection for evaluation of polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) participation in non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; OPV, oral poliovirus vaccine.

a 1995 and 2002 Eritrea DHS, 1992 Guinea DHS, 2000–2001 Mauritania DHS and 2003 South Africa DHS.

b All surveys from the DHS-II and DHS-III rounds (i.e. DHS surveys conducted between 1988 and 1997), as well as 2004 Cameroon DHS, 2005 Cape Verde DHS, 2000 Comoros MICS, 2005 Congo (Brazzaville) DHS, 2005 Ethiopia DHS, 2000 Gabon DHS, 2000 Guinea-Bissau MICS, 2008 Kenya DHS, 2009 Lesotho DHS, 2009 Liberia DHS, 2008 Madagascar DHS, 2004 and 2010 Malawi DHSs, 2007 Mauritania MICS, 2003 Mozambique DHS, 2005 Rwanda DHS, 2007 Rwanda interim DHS, 2000 Senegal MICS, 2006 Somalia MICS, 1998 South Africa DHS, 2006 Uganda DHS, 2005 and 2010 United Republic of Tanzania DHSs, 2007 Zambia DHS and 2005–2006 Zimbabwe DHS.

c 2003 Burkina-Faso DHS, 2003–2004 Madagascar DHS, 2006 Mali DHS, 2000 Rwanda DHS and 2000 Zambia MICS.

d 2008 Sierra Leone DHS and 2006–2007 Swaziland DHS.

e 2005 Burundi MICS, 2000 and 2006 Cameroon MICSs, 2000 and 2006 Central African Republic MICSs, 2000 Côte d’Ivoire MICS, 2000 Equatorial Guinea MICS, 2000 Ethiopia DHS, 2000 and 2006 Gambia MICSs, 2000 Kenya MICS, 2000 Lesotho MICS, 2000 Madagascar MICS, 2000 Malawi DHS, 2000 Niger MICS, 2000 Rwanda DHS, 2006 Sao Tome and Principe MICS, 2000 Sierra Leone MICS, 2000 Swaziland MICS, 2000 Togo MICS and 2001–2002 Zambia DHS.

f 2000–2001 Uganda DHS and 1999 United Republic of Tanzania DHS.

g 1999, 2000 and 2003 Lesotho measles SIAs; 2002–2003 Guinea measles SIA; 2003 Guinea yellow fever SIA; 2004 and 2005 Niger measles SIAs; 2005 Benin measles SIA; 2005 Côte d’Ivoire measles SIA; 2000 Gambia measles SIA; 2001 Gambia meningitis SIA; 2005 Guinea-Bissau vitamin A supplementation activity; and 2005 Togo vitamin A supplementation activity.

h 1999 Benin polio SIA; May 2005 Burkina Faso polio SIA; 1998 and 1999 Burundi polio SIAs; Feb–May 2005 Côte d’Ivoire polio SIA; 2001 Ghana polio SIA; 2002 Guinea polio SIA; 2001 Kenya polio SIA; 1997, 1998 and 1999 Mali polio SIAs; 1999, 2004 and 2005 Namibia polio SIAs; 2004 Niger polio SIA; 2002 Senegal polio SIA; and Feb–Mar 2005 Togo polio SIA.

i 2002 Ghana subnational polio SIA and 2002 Kenya subnational polio SIA.

The proportion of children with a known date of birth varied greatly across countries (Table 1). Among children with a known birthday, between 74.5% (during the 2000 Benin SIA) and 93.6% (during the 2004 Lesotho SIA) were alive at the time of the SIA. Between 94.3% and 99.8% of respondents answered the specific SIA questions. Prior use of routine immunization services varied significantly across countries: during the 2004 Lesotho SIA, only 1.3% of sampled children were non-users of routine immunization services, whereas during the 2000 Mali SIA, non-users comprised 29.2% of children.

Table 1. Data on surveys and surveyed children aged < 5 years used to evaluate participation in polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) in 15 non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries.

| Country | Year of most recent WPV casea | Survey |

Children |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of the SIAb | Type | No of months between survey and SIA. | Total no.c | Had known birth dated |

Born by time of SIAe |

Had valid SIA participation dataf |

Had health cardg |

Had health card seenh |

|||||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||||||||||

| Burundi | 2009 | 22 Sep. 1999 | MICS | 7–8 | 3 325 | 2 821 | 84.8 | 2 317 | 82.1 | 2 177 | 94.0 | 1 905 | 87.5 | 1 172 | 61.5 | ||||||

| Namibia | 2006 | 15 Jun. 2000 | DHS | 3–7 | 3 784 | 2 979 | 78.7 | 2 656 | 89.2 | 2 507 | 94.4 | 2 451 | 97.8 | 1 727 | 70.5 | ||||||

| Mali | 2011 | 20 Oct. 2000 | DHS | 3–7 | 11 109 | 9 199 | 82.8 | 8 036 | 87.4 | 7 832 | 97.5 | 5 459 | 69.7 | 2 784 | 51.0 | ||||||

| Benin | 2009 | 19 Oct. 2000 | DHS | 10–12 | 4 740 | 3 260 | 68.8 | 2 429 | 74.5 | 2 354 | 96.9 | 2 244 | 95.4 | 1 669 | 74.4 | ||||||

| Lesotho | Pre-1996 | 26 Jul. 2004 | DHS | 1–5 | 3 340 | 1 511 | 45.2 | 1 414 | 93.6 | 1 374 | 97.2 | 1 349 | 98.2 | 986 | 73.1 | ||||||

| Senegal | 2010 | 8 Oct. 2004 | DHS | 4–8 | 10 106 | 2 623 | 26.0 | 2 207 | 84.1 | 2 198 | 99.6 | 2 092 | 95.2 | 1 320 | 63.1 | ||||||

| Guinea | 2011 | 8 Oct. 2004 | DHS | 4–8 | 5 641 | 1 341 | 23.8 | 1 087 | 81.1 | 1 073 | 98.7 | 984 | 91.7 | 688 | 69.9 | ||||||

| Sierra Leone | 2010 | 8 Oct. 2004 | MICS | 11–13 | 5 246 | 4 101 | 78.2 | 3 233 | 78.8 | 3 143 | 97.2 | 2 704 | 86.0 | 1 121 | 41.5 | ||||||

| Sierra Leone | 2010 | 15 Feb. 2005 | MICS | 7–9 | 5 246 | 4 101 | 78.2 | 3 451 | 84.2 | 3 420 | 99.1 | 2 944 | 86.1 | 1 267 | 43.0 | ||||||

| Niger | 2011 | 9 Apr. 2005 | DHS | 9–13 | 8 209 | 2 228 | 27.1 | 1 714 | 76.9 | 1 683 | 98.2 | 1 190 | 70.7 | 805 | 67.6 | ||||||

| Benin | 2009 | 11 Nov. 2005 | DHS | 9–13 | 14 682 | 9 741 | 66.3 | 7 528 | 77.3 | 7 419 | 98.5 | 7 061 | 95.2 | 4 421 | 62.6 | ||||||

| Burkina Faso | 2009 | 15 Nov. 2005 | MICS | 4–7 | 5 283 | 3 383 | 64.0 | 2 974 | 87.9 | 2 947 | 99.1 | 2 796 | 94.9 | 2 376 | 85.0 | ||||||

| Guinea-Bissau | Pre-1996 | 18 Nov. 2005 | MICS | 6–8 | 5 845 | 5 288 | 90.5 | 4 608 | 87.1 | 4 473 | 97.1 | 4 280 | 95.7 | 2 923 | 68.3 | ||||||

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2011 | 11 Nov. 2005 | MICS | 9–11 | 8 604 | 7 443 | 86.5 | 5 849 | 78.6 | 5 692 | 97.3 | 5 042 | 88.6 | 3 907 | 77.5 | ||||||

| Gambia | 2000 | 11 Nov. 2005 | MICS | 1–4 | 6 543 | 6 505 | 99.4 | 6 016 | 92.5 | 6 004 | 99.8 | 5 896 | 98.2 | 3 605 | 61.1 | ||||||

| Togo | 2009 | 11 Nov. 2005 | MICS | 6–8 | 3 820 | 2 983 | 78.1 | 2 579 | 86.5 | 2 531 | 98.1 | 2 300 | 90.9 | 1 645 | 71.5 | ||||||

| Niger | 2011 | 12 Nov. 2005 | DHS | 2–6 | 8 209 | 2 228 | 27.1 | 1 999 | 89.7 | 1 963 | 98.2 | 1 403 | 71.5 | 984 | 70.1 | ||||||

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2011 | 12 May 2006 | MICS | 3–5 | 8 604 | 7 443 | 86.5 | 6 789 | 91.2 | 6 664 | 98.2 | 5 920 | 88.8 | 4 603 | 77.8 | ||||||

| Benin | 2009 | 27 May 2006 | DHS | 3–6 | 14 682 | 9 741 | 66.3 | 8 907 | 91.4 | 8 778 | 98.5 | 8 353 | 95.2 | 5 452 | 65.3 | ||||||

| Namibia | 2006 | 20 Jun. 2006 | DHS | 5–9 | 4 858 | 3 899 | 80.3 | 3 231 | 82.9 | 3 154 | 97.6 | 3 069 | 97.3 | 2 159 | 70.4 | ||||||

| Ghanai | 2008 | 6 Mar. 2010 | MoTeCH | 1–5 | 1 594 | 1 594 | 100.0 | 1 482 | 93.0 | 1 463 | 98.7 | 1 443 | 98.6 | 1 379 | 95.6 | ||||||

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; MICS, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; MoTeCH, Mobile Technology for Community Health.

a Obtained from a database maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO; available at: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/en/diseases/poliomyelitis/case_count.cfm).

b Obtained either from survey questionnaires or from a calendar of SIAs, maintained by WHO (available at: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/en/globalsummary/siacalendar/padvancedsia.cfm).

c Denotes children who were alive at the time of the survey.

d Denotes children with a known day, month and year of birth. Percentages were calculated by dividing these values by the no. of children surveyed.

e Determined by comparing the reported date of birth and the date of the SIA. Percentages were calculated by dividing these values by the no. of children with a known birth date.

f Denotes children without missing SIA survey data. Percentages were calculated by dividing these values by the no. of children born by the SIA date.

g Denotes children with a health card containing their vaccination history. Percentages were calculated by dividing these values by the no. of children without missing SIA survey data.

h Denotes children with a health card reviewed by a survey interviewer. Percentages were calculated by dividing these values by the no. of children with a health card.

i Kassena-Nankana East and West districts in the Upper East Region.

Sources: DHSs, MICSs, MoTeCH survey and WHO.

SIA participation

Full results of logistic regression analyses of the probability of SIA participation are reported in Appendix B (available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sh2813/appendix-02292012sh.pdf). SIA participation ranged from 70.2% (during the 2004 Lesotho SIA) to 96.1% (during the 1999 Burundi SIA). In most SIAs, participation was lower among infants than among children 1–4 years old. SIA participation increased with age and educational level of the mother or guardian. In 8 of 17 SIAs for which data on household wealth were available, SIA participation was highest among wealthier households. In 7 SIAs, participation was associated with residential location: 2 SIAs (the 1999 Burundi SIA and the 2005 Sierra Leone SIA) had greater participation in rural areas and 5 SIAs (the 2000 Mali SIA, the 2000 Benin SIA, the 2005 Burkina-Faso SIA, the 2005 Gambia SIA and the 2006 Namibia SIA) had greater participation in urban areas. There were regional differences in participation in all SIAs but differences associated with ethnicity were less common. Religious differences in SIA participation were observed in 6 SIAs, during which participation was lower among people with traditionalist beliefs than among Christians and Muslims.

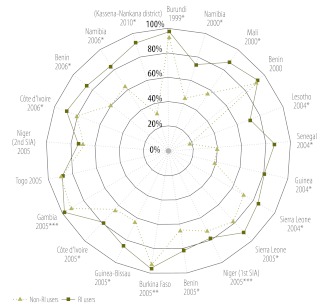

Prior use of routine services

In adjusted logistic regression analyses (Fig. 2), user participation was > 85% for 12 SIAs but non-user participation was > 85% in only 5 SIAs. In 18 of 21 SIAs, participation was significantly higher (P < 0.01 in 16 SIAs, P < 0.05 in 2 SIAs and P < 0.1 in 1 SIA), among routine immunization service users (Fig. 2). In robustness analyses, however (Appendix C and Appendix D, both available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sh2813/appendix-02292012sh.pdf), participation was higher among routine immunization service users than among non-users in all but 1 SIA, which occurred during 2000 in Benin, discussed below. These differences in SIA participation by prior use of routine immunization services were sometimes very large. For example, during the 2010 Ghana SIA in the Kassena-Nankana districts, adjusted SIA participation was 91.5% among routine immunization service users but only 32.7% among non-users (P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Participation in polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) in non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries, by use or non-use of routine immunization (RI) servicesa

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.10 (for differences in participation between RI service users and non-users, by logistic regression analysis).

a SIAs appear in chronological order, moving clockwise, starting with the 1999 Burundi SIA. Data denote the adjusted proportions of children participating in an SIA among RI users (defined as children who owned a health card containing their vaccination history) and non-RI users (defined as children who did not own a health card). Full results including estimates of coefficients for covariates are shown in Appendix B (available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sh2813/appendix-02292012sh.pdf).

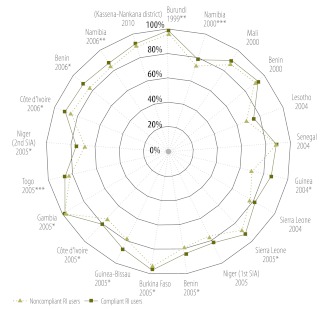

OPV compliance among users

Among routine immunization service users, the proportion of compliant children varied significantly across countries (Appendix E, available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~sh2813/appendix-02292012sh.pdf). Fewer than 60% of users had received all required routine OPV doses for their age before the 1999 Burundi SIA, the 2000 Mali SIA, the 2004 and 2005 Sierra Leone SIAs and both 2005 Niger SIAs. On the other hand, > 80% of users were compliant with the routine vaccination schedule before the 2004 Lesotho SIA and the 2006 Namibia SIA (Appendix E). SIA participation among compliant users was significantly higher than that among non-compliant ones in 14 of 21 SIAs analysed (Fig. 3). The largest difference was observed during the 2004 Guinea SIA, in which 68.8% of non-compliant routine immunization users participated, compared with 85.4% of compliant users (P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Participation in polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) in non-polio-endemic sub-Saharan African countries among users of routine immunization (RI) services, by compliance with the routine oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) schedulea

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.10 (for differences in participation between compliant and non-compliant RI service users, by logistic regression analysis).

a SIAs appear in chronological order, moving clockwise, starting with the 1999 Burundi SIA. Data denote the adjusted proportions of children participating in an SIA among compliant RI service users (defined as children who owned a health card that reflected receipt of each required OPV dose by the target age) and non-compliant RI service users (defined as children who owned a health card that did not reflect receipt of each required OPV dose by the target age).

The Benin case study

Although participation in the 2000 Benin SIA was high (> 90%) among both routine immunization service users and non-users, SIAs conducted in 2005 and 2006 had high participation among users but much lower participation among non-users (approximately 60%; Fig. 2). Investigation of the SIAs’ budgetary allocations revealed that the percentage of the budget allocated to community mobilization declined sharply, from 19.8% in 2000 to 10.1% in 2005 and 11.1% in 2006 (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) conducted in Benin between 2000 and 2006.

| Characteristic | 2000 Benin; SIA coverage high among users and non-users of RI services | 2005 Benin; SIA coverage high among users and low among non-users of RI services | 2006 Benin ;SIA coverage high among users and low among non-users of RI services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational attribute | |||

| Vaccine used | Trivalent OPV | Trivalent OPV | Trivalent OPV |

| Time since previous polio SIA (months) | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Human resource | |||

| Vaccinators (no.) | 13 856 | NA | 14 573 |

| Budgetary allocationa | |||

| Vaccines | 24.6 | 33.9 | 33.1 |

| Community mobilization | 19.8 | 10.1 | 11.1 |

| Planning, training | 9.7 | 8.4 | 8.7 |

| Transport | 8.0 | 5.7 | 5.6 |

| Other suppliesb | 7.9 | 3.8 | 4.0 |

| Monitoring, evaluation | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Staff | 27.1 | 34.4 | 33.6 |

| Total SIA budget (PPP$)c | 3 101 123 | 3 843 797 | 3 993 680 |

NA, not available; PPP$, purchasing power parity dollars; RI, routine immunization.

a Data are percentages of the total SIA budget.

b Include items associated with the cold chain, chalk used for house marking, indelible ink used for finger marking, gum boots and other waterproof gear for vaccinators and supplies (e.g. life vests and boat engines) required for reaching remote populations.

c The following exchange rates, from the Penn world table version 7,13 were used: 2000, 239.41 CFA francs per PPP$; 2005, 248.27 CFA francs per PPP$; 2006, 244.01 CFA francs per PPP$.

Sources: SIA implementation records and comprehensive budgets.

Discussion

In this study, we used data from the MICS, the DHS and a recent survey we conducted in two districts of Ghana’s Upper East Region to document patterns of participation in polio SIAs in sub-Saharan African countries where polio is not endemic. We found that a large percentage of undervaccinated children benefit from vaccination opportunities offered during SIAs every year but that SIAs only imperfectly remedy the limited reach of routine immunization services. In the 21 SIAs we analysed, reported SIA participation among routine immunization users was often significantly higher than that among non-users. Compliant users were also often more likely than non-compliant users to participate in SIAs, but these differences were of much smaller magnitude than those between users and non-users. Of 3 SIAs in Benin, the one with the highest participation among non-users had the greatest percentage of the total SIA budget invested in community mobilization.14 During the 2010 Ghana SIA, some of the possible reasons for low SIA participation among non-users of routine immunization services included inappropriate marking of houses in the targeted areas, incomplete training of volunteers, lack of local maps of the targeted areas among teams and suboptimal supervision.15

Our study has several potential limitations. First, analyses were limited to 21 of thousands of SIAs conducted since the launch of the GPEI and excluded SIAs conducted in countries where polio transmission is endemic or considered to be re-established. Also, most data were for SIAs conducted before 2006. Although analyses of the 2010 Ghana SIA suggest that large differences in SIA participation between routine immunization service users and non-users may have persisted in recent years, data from the MoTeCH survey are not nationally representative and are derived from a limited sample size. Second, data were limited to children for whom a valid birth date was reported and were thus possibly affected by sample selection bias. However, robustness analyses involving children for whom the month but not day of birth was known (Appendix C) yielded results very similar to those for children whose birth date was known (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Third, SIA participation was determined on the basis of maternal recall and self-report rather than on the basis of more objective methods (e.g. finger marking5). Although we attempted to minimize recall bias by excluding SIA data if the associated survey was conducted > 12 months after the SIA, a desire to state socially acceptable responses to survey questions might have tempted some mothers to exaggerate the extent to which their children participated in SIAs. Fourth, the criterion used to distinguish routine immunization users from non-users is a potential source of information bias. If SIAs stimulate interest in immunization among undervaccinated children, non-users who participate in an SIA might subsequently begin accessing routine immunization services, which could result in their misclassification as routine immunization service users at the time of the SIA. The results in Appendix D, however, indicate that this source of bias is unlikely to have explained the observed patterns. Fifth, our data have limitations common to retrospective studies of vaccination status (e.g. they exclude children who died or moved before the survey).16 Finally, our exploration of the factors that may explain low SIA coverage among non-users of routine immunization services was limited. It was based solely on the comparison of three SIAs conducted in one country (Benin); used only data from SIA budgets and planning documents, rather than data tracking the implementation of SIAs at the local (i.e. district) level17; and did not incorporate elements (e.g. rumours and fatigue) characterizing the demand for SIAs and immunization among local populations.

Our study nonetheless has important implications for polio eradication. First, our findings provide insights into factors explaining the recurrent importation of wild poliovirus in previously polio-free sub-Saharan countries since 2002. Specifically, differences in SIA coverage between routine immunization service users and non-users may have maintained local pockets of susceptibility to polio importation. Second, our analyses suggest that SIA monitoring in the GPEI should include an assessment of the vaccination history of children “missed” by vaccination teams during SIAs. Current monitoring practices do not include such assessment and thus do not permit identification of possible pockets of individuals susceptible to infection. Whereas the 2010 Ghana SIA met the GPEI’s quality criterion of > 90% participation in the two Kassena-Nankana districts, we found very low coverage among non-users of routine immunization services, who are most likely to be undervaccinated. Finally, our analyses have implications for strategies to improve SIA quality in the GPEI. At present, quality assessments are focused on estimating the proportion of children who were not reached during an SIA and on determining why they were not reached (e.g. refusal and conflict-related inaccessibility). Such data are descriptive and do not permit identification of the SIA characteristics (e.g. poor microplanning, lack of supervision and insufficient or ineffective community mobilization) that explain poor SIA coverage among populations at greatest risk of experiencing polio outbreaks.17 To sustain high levels of immunity against polio and achieve eradication, an ambitious agenda of operational research on the characteristics of undervaccinated children (e.g. location and socioeconomic characteristics) and the organizational determinants of SIA participation is thus urgently needed. Findings from this research will help guide SIA quality improvement strategies and help develop new interventions to promote participation in immunization activities among children who are not reached by both routine immunization services and SIAs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jacques Hassane, James Phillips, Almamy Malick Kanté and Francis Yeji.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Bateman C. Polio vaccination 'gaps'—Namibia pays the price. S Afr Med J. 2006;96:668–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutter RW, Maher C. Mass vaccination campaigns for polio eradication: an essential strategy for success. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;304:195–220. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36583-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivé JM, Risi JB, Jr, de Quadros CA. National immunization days: experience in Latin America. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(Suppl 1):S189–93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.Supplement_1.S189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birmingham ME, Aylward RB, Cochi SL, Hull HF. National immunization days: state of the art. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(Suppl 1):S183–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.Supplement_1.S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Every Last Child: strategic plan 2010–2012 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:7gHrGgWyFtsJ:www.gatesfoundation.org/polio/Documents/global-polio-eradication-initiative.pdf [accessed 23 January 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wild poliovirus type 1 and type 3 importations—15 countries, Africa, 2008-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Resurgence of wild poliovirus type 1 transmission and consequences of importation—21 countries, 2002-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:145–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichler MR, Abbas A, Kharabsheh S, Mahafzah A, Alexander JP, Jr, Rhodes P, et al. Outbreak of paralytic poliomyelitis in a highly immunized population in Jordan. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(Suppl 1):S62–70. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.Supplement_1.S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrianarivelo MR, Boisier P, Rabarijaona L, Ratsitorahina M, Migliani R, Zeller H. Mass vaccination campaigns to eradicate poliomyelitis in Madagascar: oral poliovirus vaccine increased immunity of children who missed routine programme. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:1032–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman N, Pebley AR. Health cards, maternal reports and the measurement of immunization coverage: the example of Guatemala. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1075–89. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langsten R, Hill K. The accuracy of mothers' reports of child vaccination: evidence from rural Egypt. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1205–12. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJ, Shengelia B, Gupta N, Moussavi S, Tandon A, Thierean M. Validity of reported vaccination coverage in 45 countries. Lancet. 2003;362:1022–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14411-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heston A, Summers R, Aten B. Penn World Table Version 7.0 Philadelphia: Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania; 2011. Available from: http://pwt.econ.upenn.edu/php_site/pwt_index.php [accessed 30 March 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates J, Guirguis S, Moran T, Desomer L. Disease eradication as a springboard for broader public health communication. In: Cochi S, Dowdle WR, editors. Disease eradication in the 21st century: implications for global health Cambridge: MIT Press; 2011. pp. 255–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.March GHS. 2010 NID report Accra: Ghana Health Service; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine PE, Williams TN, Aabz P, Källander K, Moulton LH, Flanagan KL, et al. Epidemiological studies of the 'non-specific effects' of vaccines: I—data collection in observational studies. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:969–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Report of the Independent Monitoring Board, October 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]