Abstract

Objective

To estimate how much more cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality could be reduced in the United Kingdom through more progressive nutritional targets.

Methods

Potential reductions in CVD mortality in the United Kingdom between 2006 (baseline) and 2015 were estimated by synthesizing data on population, diet and mortality among adults aged 25 to 84 years. The effect of specific dietary changes on CVD mortality was obtained from recent meta-analyses. The potential reduction in CVD deaths was then estimated for two dietary policy scenarios: (i) modest improvements (simply assuming recent trends will continue until 2015) and (ii) more substantial but feasible reductions (already seen in several countries) in saturated fats, industrial trans fats and salt consumption, plus increased fruit and vegetable intake. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted. Results were stratified by age and sex.

Findings

The first scenario would result in approximately 12 500 fewer CVD deaths per year (range: 5500–30 300). Approximately 4800 fewer deaths from coronary heart disease and 1800 fewer deaths from stroke would occur among men, and 3500 and 2400 fewer, respectively, would occur among women. More substantial dietary improvements (no industrial trans fats, reduction in saturated fats and salt and substantial increases in fruit and vegetable intake) could result in approximately 30 000 fewer (range: 13 300–74 900) CVD deaths.

Conclusion

Excess dietary trans fats, saturated fats and salt, along with insufficient fruits and vegetables, generate a substantial burden of CVD in the United Kingdom. Further improvements resembling those attained by other countries are achievable through stricter dietary policies.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer le niveau de réduction potentielle de la mortalité liée aux maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) au Royaume-Uni par le biais d'objectifs nutritionnels plus progressistes.

Méthodes

Les réductions potentielles de la mortalité par MCV au Royaume-Uni entre 2006 (base) et 2015 ont été estimées par la synthèse des données sur la population, l'alimentation et la mortalité parmi les adultes âgés de 25 à 84 ans. L’effet des modifications spécifiques du régime alimentaire sur la mortalité par MCV a été obtenu à partir de méta-analyses récentes. La possible diminution du nombre de décès dus aux maladies cardiovasculaires a ensuite été estimée pour deux scénarios de politique nutritionnelle: (i) des améliorations mineures (en supposant simplement que les tendances récentes se poursuivront jusqu'en 2015) et (ii) des réductions plus importantes, mais envisageables (déjà observées dans plusieurs pays) dans les graisses saturées, les graisses trans industrielles et dans la consommation de sel, accompagnées d'une augmentation de la consommation de fruits et légumes. Une analyse de sensibilité probabiliste a été réalisée. Les résultats ont été classés selon l'âge et le sexe.

Résultats

Le premier scénario se traduirait par une réduction annuelle d'environ 12 500 décès par MCV (intervalle: 5500-30 300). Environ 4800 décès liés aux maladies coronariennes et 1800 décès par infarctus seraient évités chez les hommes, pour respectivement 3500 et 2400 décès chez les femmes. Des mesures alimentaires plus strictes (pas de matières grasses trans industrielles, une réduction de la consommation en graisses saturées et en sel, ainsi que des augmentations substantielles de la consommation de fruits et légumes) pourraient se traduire par une réduction d'environ 30 000 décès par MCV (intervalle: 13 300 à 74 900).

Conclusion

Les excès en graisses trans alimentaires, en graisses saturées et en sel, ainsi que des apports insuffisants en fruits et légumes génèrent un impact substantiel des MCV au Royaume-Uni. Des améliorations semblables à celles obtenues dans d'autres pays sont réalisables grâce à des politiques alimentaires plus strictes.

Resumen

Objetivo

Calcular cuánto más podría reducirse la mortalidad por enfermedades cardiovasculares en el Reino Unido a través de objetivos nutricionales más progresivos.

Métodos

Se calculó la reducción potencial de la mortalidad por enfermedades cardiovasculares en el Reino Unido entre los años 2006 (año de referencia) y 2015 sintetizando los datos acerca de la población, la dieta y la mortalidad entre adultos con edades comprendidas entre los 25 y los 84 años. El efecto de unos cambios dietéticos concretos sobre la mortalidad por enfermedades cardiovasculares se obtuvo a través de metaanálisis recientes. La posible reducción de los fallecimientos por enfermedades cardiovasculares se calculó entonces para dos supuestos con políticas dietéticas distintas: (i) mejoras moderadas (se asume simplemente que las tendencias recientes continuarán hasta el año 2015) y (ii) reducciones más importantes pero factibles (como ya se han observado en muchos países) en el consumo de grasas saturadas, grasas trans industriales y sal, unidas a un mayor consumo de frutas y verduras. Se llevó a cabo un análisis de sensibilidad probabilístico y los resultados se estratificaron según la edad y el sexo.

Resultados

El primer supuesto tendría como resultado aproximadamente 12 500 fallecimientos menos por enfermedad cardiovascular al año (margen: 5500–30 300). Entre los hombres se registrarían aproximadamente 4800 fallecimientos menos por cardiopatías coronarias y 1800 fallecimientos menos por accidentes cerebrovasculares. En el caso de las mujeres, se observaría una reducción de 3500 y 2400 fallecimientos menos, respectivamente. Unas mejoras dietéticas más sustanciales (erradicación de las grasas trans industriales, reducción de las grasas saturadas y la sal, unidas a un aumento en el consumo de frutas y verduras) podrían traducirse en aproximadamente 30 000 fallecimientos menos (margen: 13 000 – 74 900) por enfermedades cardiovasculares.

Conclusión

El exceso de grasas trans, grasas saturadas y sal, así como un consumo insuficiente de fruta y verdura en la dieta genera una carga considerable de fallecimientos por enfermedades cardiovasculares en el Reino Unido. A través de políticas alimentarias más estrictas pueden alcanzarse mejoras similares a las obtenidas por otros países.

ملخص

الغرض

تقدير حجم الانخفاض الذي يمكن أن يطرأ على وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية (CVD) في المملكة المتحدة من خلال أهداف تغذوية أكثر تطوراً.

الطريقة

تم تقدير الانخفاضات المحتملة في وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية في المملكة المتحدة في الفترة ما بين عامي 2006 (خط الأساس) و2015 عن طريق استخلاص البيانات المتعلقة بالسكان والنظام الغذائي والوفيات بين البالغين الذين تتراوح أعمارهم ما بين 25 و84 سنة. وتم الحصول على أثر تغيرات أنظمة غذائية محددة على وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية من التحليلات الوصفية الحديثة. وتلا ذلك تقدير الانخفاض المحتمل في وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية بالنسبة لسيناريوهين يتعلقان بسياسة الأنظمة الغذائية: (1) التحسينات المتواضعة (ببساطة افتراض استمرار الاتجاهات الحديثة حتى عام 2015) و(2) الانخفاضات الملحوظة ذات الجدوى (تم مشاهدة ذلك بالفعل في عدد من البلدان) في الدهون المشبعة والدهون الصناعية المتحولة واستهلاك الملح، بالإضافة إلى زيادة تناول الفواكه والخضروات. وتم إجراء تحليل احتمالي للحساسية. كما تم ترتيب النتائج بحسب العمر والجنس.

النتائج

سينتج عن السيناريو الأول انخفاض وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية بمقدار 12500 حالة وفاة سنوياً تقريبًا (النطاق: 5500 - 30300). وسيحدث انخفاض في الوفيات الناجمة عن مرض القلب التاجي بين الرجال بمقدار 4800 حالة وفاة وعن السكتة بمقدار 1800 حالة وفاة، وسيحدث انخفاض في الوفيات الناجمة عن مرض القلب التاجي والسكتة بين النساء بمقدار 3500 حالة وفاة و2400 حالة وفاة على التوالي. وسينتج عن زيادة التحسينات الملحوظة التي يتم إدخالها على الأنظمة الغذائية (تجنب الدهون الصناعية المتحولة وخفض الدهون المشبعة والملح والزيادات الكبرى في تناول الفواكه والخضروات) انخفاض في الوفيات بمقدار 30000 حالة وفاة تقريباً (النطاق: 13300 - 74900) من حالات الوفاة الناجمة عن الأمراض القلبية الوعائية.

الاستنتاج

يسفر فرط الدهون المتحولة والدهون المشبعة والملح مع تناول كميات غير كافية من الفواكه والخضروات في الأنظمة الغذائية عن عبء كبير فيما يخص الأمراض القلبية الوعائية في المملكة المتحدة. ويمكن تحقيق المزيد من التحسينات المشابهة لتلك التي تم تحقيقها بواسطة البلدان الأخرى من خلال سياسات أكثر صرامة للأنظمة الغذائية.

摘要

目的

估计通过更进一步的营养目标能够使英国心血管疾病(CVD)死亡率有多少更大程度的降低。

方法

在2006 年(基线)至2015 年期间,通过综合25 至84 岁成年人的人口、饮食和死亡率数据,估计英国CVD死亡率潜在减少的情况。从最近的元分析中获得特定的规定饮食变化对 CVD 死亡率的影响。针对两种饮食政策情况估计CVD死亡数的潜在减少,这两种情况是:(1)适度改善(简单地假设最近的趋势将持续至2015 年)和(2)更显著但切实可行地减少(已在一些国家看到)饱和脂肪、工业反式脂肪和盐的消费量,增加水果和蔬菜的摄入量。进行概率敏感性分析。结果按年龄和性别分级。

结果

第一种情况下,每年会减少大约12500 个CVD死亡数(范围:5500-30300)。男性冠心病死亡数大约减少4800 个,中风死亡数大约减少1800 个,女性则分别减少了3500 个和2400 个。更加显著的饮食改进(不食用工业反式脂肪,减少饱和脂肪和盐,大量增加水果和蔬菜的摄入)则会减少大约 30000 个(范围:13300-74900)CVD 死亡数。

结论

饮食上过量的反式脂肪、饱和脂肪和盐,以及水果和蔬菜摄入不足,造成英国 CVD 的沉重负担。通过更加严格的饮食政策可实现与其他国家类似的进一步改善。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить, как можно снизить смертность от сердечнососудистых заболеваний (ССЗ) в Соединенном Королевстве путем введения более прогрессивных требований к продуктам питания.

Методы

Потенциальное снижение смертности от ССЗ в Соединенном Королевстве за период с 2006 г. (базовый уровень) по 2015 г. было оценено путем синтеза данных о населении, диетических предпочтениях и смертности среди взрослого населения в возрасте от 25 до 84 лет. Влияние конкретных изменений диеты на уровень смертности от ССЗ было рассчитано на основе результатов последних мета-аналитических исследований. Потенциал снижения смертности от ССЗ был затем оценен для двух сценариев политики в отношении продуктов питания: (i) скромные улучшения (если просто предположить, что последние тенденции сохранятся до 2015 г.) и (ii) более существенное, но правдоподобное сокращение (уже наблюдаемое в ряде стран) содержания в рационе насыщенных жиров, транс-жиров и потребления соли, а также повышение потребления фруктов и овощей. Был проведен вероятностный анализ чувствительности. Результаты были стратифицированы по возрасту и полу.

Результаты

Согласно первому сценарию количество смертей от ССЗ снизится приблизительно на 12 500 в год (диапазон: 5500-30 300). Приблизительно, среди мужчин на 4800 сократится количество смертей от ишемической болезни сердца и на 1800 – от инсульта, а среди женщин – на 3500 и 2400, соответственно. Более существенные улучшения в диете (отказ от промышленных транс-жиров, снижение потребления насыщенных жиров и соли, а также существенное увеличение потребления фруктов и овощей) может привести к снижению смертности от ССЗ приблизительно на 30 000 (диапазон: 13 300-74 900).

Вывод

Избыточное потребление транс-жиров, насыщенных жиров и соли, а также недостаточное потребление фруктов и овощей способствуют увеличению заболеваемости ССЗ в Соединенном Королевстве. Дальнейшие улучшения, аналогичные уже имеющим место в других странах, могут достигаться путем введения более строгой политики в отношении продуктов питания.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death in the United Kingdom, where coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke cause 150 000 deaths every year. Of these CVD deaths, more than 40 000 occur prematurely, in people younger than 75 years.1 Apart from smoking, the main risk factors for CVD are elevated blood cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, obesity and diabetes, all related to poor eating habits. According to the United Kingdom’s government report for 2008, poor nutrition causes more than 70 000 preventable premature deaths annually, mainly from CVD.2 A recent paper estimated this figure at 33 000 deaths.3 Regardless, the health effects of poor nutrition pose an enormous economic burden; poor diet alone costs the government of the United Kingdom an annual 6 billion pounds sterling.3

CVD is consistently associated with the so-called “Western” diet, consisting mainly of dairy products, meat and processed foods.2–5 CVD mortality rates are twice as high among segments of society that follow such a diet than among people who eat sensibly.2–4 Salt, sugar, saturated fat and trans fats are harmful when consumed in excess; conversely, fruit and vegetables (which contain potassium, antioxidants and fibre), polyunsaturated fats (e.g. from sunflower and canola oil), mono-unsaturated fats (e.g. from olive oil), whole grains, pulses, nuts and fish have consistently shown a protective effect against CVD.2–4

In the United Kingdom and the United States of America, processed foods and fast, takeaway foods are the main dietary sources of excess salt, saturated fats, trans fats and excess calories. In 2001 the Food Standards Agency (FSA) of the United Kingdom began working with industry to develop a range of healthy food strategies,5 including voluntary product reformulation, clearer (traffic light) package labelling of nutrient levels and media campaigns. The FSA’s salt strategy helped reduce the average daily salt intake by nearly 1 g between 2001 and 2008 (from 9.5 to 8.6 g, respectively).6 However, outside the United Kingdom stricter regulatory policies have resulted in much greater reductions.7 For instance, between 1979 and 2002 Finland’s daily average salt intake fell from 12 g to 9 g.7

The FSA’s strategy in the United Kingdom also sought to reduce the daily average intake of saturated fat from 13.3% to 11% of total food energy by 2010,5 yet currently the figure stands at 12.8%.6 Finland and Iceland, on the other hand, reduced saturated fat intake by 5% of total energy in one or two decades.4,8 Furthermore, in the traditional Italian and Japanese diets and the successful DASH and OMNI diets, 6% of total energy comes from saturated fats.9

Dietary industrial trans fats, resulting from the partial hydrogenation of vegetable oils, are particularly toxic. By raising serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL or “bad” cholesterol) and reducing high-density lipoprotein (HDL or “good” cholesterol), they substantially increase the risk of CHD and stroke.10 The Government of the United Kingdom currently recommends consuming less than 2% of total energy in the form of trans fats. Average trans fat intake for adults in the United Kingdom reportedly represents only 0.8% of total energy consumption.6,11 However, the true value is probably closer to 1% because routine surveys tend to underestimate consumption outside the home, particularly from fast foods. Furthermore, ethnic minorities, low-income adults and children probably consume substantially more.12 In contrast, Denmark’s 2004 legislative ban eliminated the consumption of dietary industrial trans fats within a year (from a baseline of 4%).13 Currently Austria, Canada, Iceland, Switzerland and several states in the United States are aggressively working to eliminate trans fats.10

Finally, the average quantity of fruit and vegetables eaten daily in the United Kingdom has levelled at about 245 g since 2003.6 This is much lower than the pragmatic target of 400 g (five portions) and less than half of the 600 g per day already achieved in much of France, Greece and Italy and now recommended for the entire European Union.14

The FSA reasonably estimated that approximately 7000 CVD deaths would be averted annually if people in the United Kingdom reached the current (modest) dietary targets for saturated fat and trans fats.5,11 However, the potential benefit of more ambitious dietary targets remains unclear. We therefore estimated the potential reduction in CVD mortality achievable in the United Kingdom if stricter, yet feasible food policies were established, as in other countries, to further decrease the intake of salt, saturated fats and trans fats and increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

Methods

The potential decrease in CVD deaths was estimated for two policy scenarios:

conservative: modest dietary improvements, based on assuming that recent trends will continue to 2015, yielding further small reductions in intake (by 0.5% of total energy for trans fat; by 1% of total energy for saturated fat; by 1 g per day for salt) and one additional daily portion of fruit or vegetables;

aggressive: more substantial (but feasible) dietary improvements, as seen elsewhere, yielding larger reductions in intake (by 1% of total energy for trans fat; by 3% of total energy for saturated fat; by 3 g per day for salt) and three additional daily portions of fruit or vegetables.

We developed a spreadsheet model to quantify the deaths potentially averted by adopting healthier food policies. Contemporary data on diet and mortality among adults aged 25 to 84 years in the United Kingdom were obtained from national surveys and official statistics. Potential reductions in CVD mortality were then calculated by synthesizing age-specific population, dietary and mortality data (Appendix A, available at: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/medchamps/assets/WHObulletinUKFoodPolicyOptionsAppend2April12.pdf).1,6

Modelling approach

The CVD deaths averted by each food policy intervention were calculated by multiplying the number of deaths observed in the United Kingdom in 2006 (baseline year) for all age groups between 25 and 84 years by the reduction in the relative risk (RR) of dying from CHD or stroke. The reductions in RR were estimated on the basis of age- and sex-specific values obtained from the largest and most recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews of large controlled trials and observational studies (Appendix B, available at: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/medchamps/assets/WHObulletinUKFoodPolicyOptionsAppend2April12.pdf).

Reduced trans fats

We first assumed, under the conservative policy scenario, that by 2015 the fraction of total energy derived from trans fats would have decreased by an additional 0.5%. We subsequently assumed, under the aggressive policy scenario, that a legislative ban on industrial trans fats would essentially eliminate their intake, as witnessed in Denmark,13 and would further decrease trans fats intake by approximately 1% of total energy.

We then used the RR from the largest meta-analysis to estimate the CVD deaths that would be averted under the aggressive scenario.15 If the 2% total energy derived from industrial trans fats were completely replaced by monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, mortality from CHD would drop by approximately 23%.15 Thus, if the total energy derived from trans fats were reduced by 0.5%, the number of CHD deaths would drop by approximately 6%.15

The number of CHD deaths averted under the aggressive scenario was then calculated by multiplying by 0.06 the number of deaths from CHD in the United Kingdom in 2006 in each age group. For example, in 2006 11 947 CHD deaths occurred among men aged 65 to 74 years. The estimated number of CHD deaths averted in this group would thus be approximately:

| 11 947 × 0.06 = 950 |

This process was repeated for all other age groups and for both men and women.

We followed a similar procedure to calculate the number of deaths from stroke potentially averted under the aggressive scenario. If the total energy derived from trans fats were reduced by 0.5%, stroke deaths would be reduced by approximately 3% in both men and women (Appendix B).15

Reduced saturated fats

We assumed that by 2015 the fraction of total energy derived from saturated fats would have been reduced by an additional 1% under the conservative policy scenario, and by an additional 3% under the aggressive policy scenario (from an average of 12.8%5,6 to 9.8%). Using summary estimates from Mozaffarian et al.’s meta-analysis,16 we determined that replacing the 5% of total energy derived from saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats would reduce CHD mortality by approximately 11.5%.16 However, since complete replacement of saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats would be an unrealistic goal, we assumed that only half of the saturated fat would be replaced by polyunsaturated fat and the other half by monounsaturated fat. This would effectively halve the reduction in deaths from both CHD and stroke.16

Reduced salt

We assumed that by 2015 the average salt intake would have decreased by 1 g per day in the conservative scenario and by 3 g per day in the aggressive policy scenario (i.e. from 8.6 to 5.6 g).7 The number of CHD deaths preventable by reducing daily salt intake by 1 g and 3 g was then calculated, as for other nutrients, by multiplying the number of deaths from CHD in the United Kingdom in 2006 by the predicted percentage reduction in CHD deaths. Based on a meta-analysis by Strazzullo et al., we determined that reducing daily salt intake by 5 g (equivalent to 2000 mg less sodium per day) would translate into approximately 17% fewer CHD deaths and approximately 23% fewer stroke deaths annually.17

We followed the same procedure to calculate the potential reduction in deaths from stroke.

Increased fruits and vegetables

We assumed that by 2015 the average intake of fruits and vegetables would have increased by one daily portion of either (from the current average of three portions to four) in the conservative policy scenario and by three portions (i.e. to 500 g or about six portions daily) in the aggressive policy.14

One additional portion a day would reduce CHD deaths by approximately 4% and stroke deaths by approximately 5%, according to Dauchet et al.18,19 To calculate the CHD deaths averted by one and three additional daily portions of fruit and vegetables, we multiplied the number of CHD deaths observed in 2006 by 0.04 and the number of deaths from stroke by 0.05.

Effect of age on mortality

We incorporated age attrition into our model using a method followed by leading cardiovascular epidemiologists.20,21 Specifically, we assumed that the reduction in deaths from CVD associated with a change in the intake of specific macronutrients decreased with age. We modelled this age gradient to mirror the age-specific decreases in the risk of death from CVD associated with both hypertension and elevated total cholesterol.20,21

Cumulative effects: Like other researchers,8,16,17 we assumed that simultaneous improvements in the intake of all macronutrients would have a cumulative rather than a merely additive effect on mortality. For instance, if a reduction of 3 g in daily salt intake had already reduced deaths from CVD by approximately 20%, any additional benefit from reducing trans fats could only act on the residual risk, namely, 80% (i.e. 1 − 0.20).

We therefore estimated the total benefit using the following standard formula:

| Total benefit = 1 − [(1 − a) × (1 − b) × (1 − c) × (1 − d)] |

where a, b, c and d represent the percentage reductions in deaths for changes in the intake of salt, saturated fat, trans fats and fruit and vegetables, respectively.8,16,17

Sensitivity analyses

All modelling involves uncertainty. We therefore explored the effects of changes in food policy on CVD risk factors and deaths by performing a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. The uncertainty of the hazards ratio and the RR parameters were characterized using a log-normal distribution. We performed Monte Carlo simulations, allowing the parameters based on the effect sizes obtained from the literature to vary stochastically. All calculations were performed separately for men and women and were stratified by age. Results were rounded to the nearest hundred and summarized as medians; 95% CIs for the median were generated using the bootstrap percentile method in Stata version 9 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America).22

Results

Conservative scenario

In 2006 (the base year), 149 840 CVD deaths occurred in the United Kingdom (94 660 from CHD and 55 180 from stroke). Given population ageing and growth, by 2015 an estimated 168 520 CVD deaths will occur in the United Kingdom (107 140 CHD and 61 380 stroke deaths), representing a rise of approximately 11% if 2006 rates do not change (Appendix C, available at: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/medchamps/assets/WHObulletinUKFoodPolicyOptionsAppend2April12.pdf).

Reducing the total energy from trans fats by 0.5% and from saturated fat by 1%, reducing salt consumption by 1 g per day, and increasing fruit and vegetable intake by 1 portion per day could result in approximately 12 500 fewer CVD deaths (minimum: 5490; maximum: 30 260) (Table 1). This would represent an 8% reduction from the total CVD deaths otherwise expected in 2015 in the United Kingdom.

Table 1. Overall annual falls in deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke potentially attributable to (A) modest and (B) more substantial dietary improvements, United Kingdom.

| Total |

Decreased trans fats |

Decreased saturated fats |

Decreased salt |

Increased fruit and vegetables |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fewer deaths | Min. | Max. | Fewer deaths | Min. | Max. | Fewer deaths | Min. | Max. | Fewer deaths | Min. | Max. | Fewer deaths | Min. | Max. | |||||

| A | |||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 6600 | 2950 | 16 040 | 1900 | 980 | 3690 | 2000 | 1040 | 3880 | 1100 | 250 | 4890 | 1600 | 680 | 3580 | ||||

| Women | 5900 | 2540 | 14 220 | 1600 | 840 | 3130 | 2000 | 1000 | 3760 | 1200 | 320 | 4610 | 1100 | 380 | 2720 | ||||

| Total | 12 500 | 5490 | 30 260 | 3500 | 1820 | 6820 | 4000 | 2040 | 7640 | 2300 | 570 | 9500 | 2700 | 1060 | 6300 | ||||

| B | |||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 15 850 | 7120 | 39 320 | 2500 | 1310 | 4740 | 5600 | 2960 | 10 910 | 3200 | 820 | 13 310 | 4400 | 2030 | 10 360 | ||||

| Women | 14 100 | 6160 | 35 560 | 2200 | 1160 | 4090 | 5500 | 2950 | 10 680 | 3300 | 920 | 12 740 | 3000 | 1130 | 8050 | ||||

| Total | 29 900 | 13 280 | 74 880 | 4700 | 2500 | 8800 | 11 200 | 5900 | 21 600 | 6600 | 1700 | 26 000 | 7400 | 3160 | 18 410 | ||||

min., minimum; max, maximum.

Approximately 3500 of the 12 500 fewer CVD deaths would result from a decrease of 0.5% in the total energy derived from trans fats; around 4000 from a decrease of 1.0% in the total energy derived from saturated fats; approximately 2300 from a decrease of 1 g in salt consumption, and about 2700 from one additional portion of fruit or vegetables daily. (Table 1)

The 12 500 fewer CVD deaths would comprise approximately 4800 fewer deaths from CHD among men (range: 2050–12 030) and 3500 (range: 1500–8700) fewer among women, and in 1820 fewer deaths from stroke in men (range: 900–4000) and 2400 in women (range: 1050–5500). Approximately 30% of the specific mortality decrease in men and 10% in women would represent reductions in people younger than 65 years (Table 2).

Table 2. Age-specific falls in deaths from annual coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke potentially attributable to modesta dietary improvements, United Kingdom.

| Decrease in CHD deaths |

Decrease in stroke deaths |

Decrease in total CVD deaths |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best estimate | Min. | Max. | Best estimate | Min. | Max. | Best estimate | Min. | Max. | |||

| Men | |||||||||||

| All ages (years) | 4800 | 2000 | 12 000 | 1800 | 900 | 4000 | 6600 | 2900 | 16 000 | ||

| 25–34 | 30 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 80 | ||

| 35–44 | 180 | 70 | 450 | 50 | 20 | 90 | 230 | 90 | 540 | ||

| 45–54 | 440 | 180 | 1100 | 90 | 60 | 210 | 530 | 240 | 1310 | ||

| 55–64 | 770 | 340 | 1920 | 140 | 60 | 320 | 910 | 400 | 2240 | ||

| 65–74 | 990 | 420 | 2490 | 270 | 140 | 600 | 1260 | 560 | 3090 | ||

| 75–84 | 2390 | 1040 | 6020 | 1270 | 620 | 2760 | 3660 | 1660 | 8780 | ||

| < 65 | 1420 | 590 | 3520 | 280 | 140 | 650 | 1700 | 730 | 4170 | ||

| < 75 | 2410 | 1010 | 6010 | 550 | 280 | 1250 | 2960 | 1290 | 7260 | ||

| Women | |||||||||||

| All ages (years) | 3500 | 1500 | 8700 | 2400 | 1000 | 5500 | 5900 | 2500 | 14 000 | ||

| 25–34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | ||

| 35–44 | 40 | 20 | 100 | 30 | 10 | 80 | 70 | 30 | 180 | ||

| 45–54 | 90 | 40 | 230 | 70 | 30 | 150 | 160 | 70 | 380 | ||

| 55–64 | 210 | 100 | 540 | 100 | 40 | 210 | 310 | 140 | 750 | ||

| 65–74 | 460 | 200 | 1130 | 210 | 90 | 450 | 670 | 290 | 1580 | ||

| 75–84 | 2680 | 1150 | 6690 | 1970 | 860 | 4620 | 4650 | 2010 | 11 310 | ||

| < 65 | 340 | 160 | 870 | 200 | 80 | 460 | 540 | 240 | 1330 | ||

| < 75 | 800 | 360 | 2000 | 410 | 170 | 910 | 1210 | 530 | 2910 | ||

CVD, cardiovascular disease; min., minimum; max, maximum.

a 1% less energy from saturated fat, 0.5% less energy from trans fat, a decrease in salt intake of 1 g a day and one additional portion of fruit and vegetables daily, adjusted for cumulative effects.

Aggressive scenario

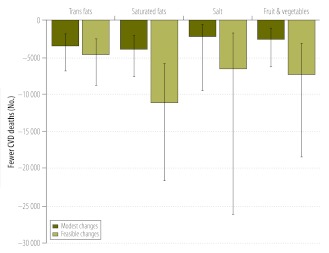

Fig. 1 shows the potential reduction in CVD deaths for each dietary scenario, bounded by minimum and maximum estimates from the sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 1.

Estimated annual reductions in deaths from cardiovascular disease (CVD) with modest and more substantial but feasible dietary improvements, United Kingdom

The more substantial decreases in harmful macronutrients and increased consumption of fruit and vegetables could result in approximately 29 900 fewer CVD deaths per year (range: 13 300–74 900) (Table 1 and Table 3). This would represent a reduction in total CVD deaths in the United Kingdom of approximately 20%.

Table 3. Age-specific falls in deaths from annual coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke potentially attributable to more substantiala dietary improvements, United Kingdom.

| Decrease in CHD deaths |

Decrease in stroke deaths |

Decrease in total CVD deaths |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best estimate | Min.b | Max.b | Best estimate | Min.b | Max.b | Best estimate | Min.b | Max.b | |||

| Men | |||||||||||

| All ages (years) | 11 000 | 4 680 | 29 000 | 4 900 | 2 400 | 10 300 | 15 800 | 7 100 | 39 300 | ||

| 25–34 | 50 | 20 | 120 | 30 | 20 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 200 | ||

| 35–44 | 380 | 160 | 950 | 120 | 50 | 230 | 500 | 210 | 1 180 | ||

| 45–54 | 960 | 420 | 2 540 | 230 | 110 | 460 | 1 190 | 530 | 3 000 | ||

| 55–64 | 1 730 | 750 | 4 520 | 370 | 190 | 780 | 2 100 | 940 | 5 300 | ||

| 65–74 | 2 280 | 990 | 6 120 | 740 | 370 | 1 560 | 3 020 | 1 360 | 7 680 | ||

| 75–84 | 5 580 | 2 340 | 14 810 | 3380 | 1 700 | 7 150 | 8 960 | 4 040 | 21 960 | ||

| < 65 | 3 120 | 1 350 | 8 130 | 750 | 370 | 1 550 | 3 870 | 1 720 | 9 680 | ||

| < 75 | 5 400 | 2 340 | 14 250 | 1490 | 740 | 3 110 | 6 890 | 3 080 | 17 360 | ||

| Women | |||||||||||

| All ages (years) | 8 000 | 3 400 | 21 400 | 6 000 | 2 700 | 14 200 | 14 100 | 6 200 | 35 500 | ||

| 25–34 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 50 | 20 | 10 | 90 | ||

| 35–44 | 90 | 40 | 240 | 90 | 30 | 210 | 180 | 70 | 450 | ||

| 45–54 | 220 | 90 | 560 | 160 | 80 | 370 | 380 | 170 | 930 | ||

| 55–64 | 500 | 210 | 1 320 | 220 | 90 | 540 | 720 | 300 | 1 860 | ||

| 65–74 | 1 060 | 450 | 2 750 | 500 | 230 | 1 200 | 1 560 | 680 | 3 950 | ||

| 75–84 | 6 170 | 2 630 | 16 470 | 5 070 | 2300 | 11 810 | 11 240 | 4 930 | 28 280 | ||

| < 65 | 810 | 340 | 2 160 | 490 | 210 | 1 170 | 1 300 | 550 | 3 330 | ||

| < 75 | 1 870 | 790 | 4 910 | 990 | 440 | 2 370 | 2 860 | 1 230 | 7 280 | ||

CVD, cardiovascular disease; min., minimum; max, maximum.

a 3% less energy from saturated fat, 1% less energy from trans fat, a decrease in salt intake of 3 g per day and 3 additional portions of fruit and vegetables daily, adjusted for cumulative effects.

b From sensitivity analyses.

Legislation to effectively eliminate the consumption of trans fats (to reach 0% of total energy) could result in approximately 4700 fewer deaths (range: 2500–8800) per year.

A reduction of 3% in total energy from saturated fats (from 12.8% to 9.8% of total energy) could result in approximately 11 200 fewer deaths (range: 5900–21 600).

A daily reduction of 3 g in salt intake (from 8.6 to 5.6 g per day) might generate approximately 6600 fewer CVD deaths (range: 1700–26 000) per year, while an additional three portions of fruit and vegetables daily could result in approximately 7420 fewer deaths (range: 3160–18 410).

Sensitivity analyses

The relative mortality contributions from these dietary changes remained reasonably consistent in robust sensitivity analyses (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Discussion

Our conservative estimates suggest that modest dietary improvements in the United Kingdom could avert approximately 12 000 annual deaths from CVD by 2015. However, more substantial improvements could avert about 30 000 CVD deaths annually (still fewer than recorded elsewhere). This would represent a 20% reduction in CVD deaths in the United Kingdom, almost one third of which would have occurred prematurely (< 75 years). These results remained robust in the sensitivity analysis.

The more substantial improvements would probably require more radical policy interventions. In a recent US study, approximately 40% of all premature CVD deaths (in people less than 70 years of age) might be avoided by optimizing various dietary risk factors.23 The modest discrepancies between this study’s findings and ours could well reflect methodological differences, since Danaei et al. optimistically assumed ideal dietary intake targets that practically eliminated the risk factor.23 Two recent US studies on salt reduction also reported comparable mortality decreases, along with impressive cost savings.22,24 Furthermore, comparable cost savings might be confidently anticipated for all population-wide dietary improvements.25,26

Our estimate of approximately 4700 fewer CVD deaths following trans fat elimination is also reassuringly close to the 7000 quoted in a recent BMJ editorial.10 The benefit for individuals and ethnic groups with insulin resistance may be even greater.10,15 In Denmark, legislation passed in 2004 banning industrial trans fats resulted in a rapid drop to zero consumption.13 After initial opposition, the EU slowly relented and subsequently discussed a ban across Europe.27 Following Denmark, several countries, including Austria, Canada, Iceland and Switzerland (and several US cities and states), have recently taken steps to reduce or ban industrial trans fats in food.10 Canada was the first country to require that the trans fats levels in pre-packaged foods be included on the mandatory nutrition facts table. Though less powerful, labelling regulations inform consumers, motivate industry to reformulate its products and favourably influence social norms. Many manufacturers have now reduced trans fat content.28 In Seattle, a programme to phase out industrial trans fats in fast food outlets encountered surprisingly little opposition from commercial interests; most stakeholders apparently considered it a logical step.29

Diet powerfully contributes to health inequity. Low-income groups, which also suffer the highest burden of CVD and other chronic diseases, have consistently worse diet patterns.30,31 The Government of the United Kingdom has spent over a decade promoting fruit and vegetable consumption, but with frustratingly small improvements.6 Social marketing campaigns and free fruit schemes for schools have clearly not sufficed. Energy-dense, nutrient-poor “junk food” remains cheap and is aggressively marketed,32 whereas fruit and vegetables remain relatively expensive.2,30 Improvements will clearly require additional structural changes.25,32–34

Policy decisions at the European level can powerfully affect food availability and consumption at the national level, both directly and indirectly. The EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which massively influences agriculture and nutrition across Europe, has an annual expenditure of approximately 45 billion euros. This sum represents about 45% of the overall EU budget.27 To deal with the historical threat of food shortages, the CAP has tended to increase the availability of cheap saturated fats while raising the price of and reducing the availability of healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables.14,33,34 CAP reform is urgently needed and should ideally incorporate Finland’s request to the EU for “health in all policies” (including agriculture).

Other effective interventions also exist. Lessons from tobacco control appear surprisingly relevant. The key targets are affordability, accessibility and acceptability.32 If the new government of the United Kingdom is seriously intent upon reducing the double burden of childhood obesity and adult CVD, taxing junk food and using the revenue to subsidize the fresh fruit and vegetable industry would be both feasible and cost-saving, even in an economic recession.10,22,24–26

Our study has several strengths. The methods employed are transparent and easily replicated. Risk factors were treated as continuous rather than categorical variables.35 Diverse but realistic policy scenarios were examined, based upon changes actually observed in other European countries. We also assumed that the benefits would be cumulative rather than additive.36 The estimated 12 000 deaths per year with modest dietary improvements were consistent with FSA estimates based on less rigorous dietary targets.5,11 Our conservative estimates did not include the potential benefits of increasing the intake of nuts, whole grains, fibre and fish; these would have further reduced mortality.37

Our study also has limitations. We did not explicitly model lag times. However, substantial reductions in deaths from CVD following dietary changes can occur very rapidly in randomized cohorts and entire populations.28,38,39 We also assumed that the effects of food policies on dietary intake in the United Kingdom would be quantitatively similar to those in other countries, without explicitly considering political, commercial, cultural and socioeconomic differences or whether other countries’ baseline dietary values were high or low. We also assumed commercial vested interests could be minimised. However, recent notable events include the industry lobbying behind the United Nations’ recent high-level meeting on non-communicable diseases, and the undermining or sabotage of effective interventions such as EU’s front-of-pack food labelling.40,41 The DASH and Omni Heart randomized trials have demonstrated, nonetheless, that individuals can rapidly improve their dietary intake substantially and over the long term, even in the absence of the supportive social environments provided by healthy policies.9

We assumed that trans fats would be replaced by an equal mixture of “good” monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, not by “bad” saturated fats (as observed in Canada28). We also assumed that changes in dietary variable would be similar across all age groups. Variance and skew could be assessed in future models, along with compression of morbidity, social stratification and cumulative benefits over a lifetime.

Another assumption was that any effects of dietary changes on mortality would wane with increasing age, as with cholesterol and blood pressure.20,21 Despite this, the greatest benefits were observed in individuals over 75 years of age. Furthermore, dietary changes may be more pronounced in younger people, meaning greater long-term benefits. We did not explicitly consider competing risks. However, healthier food and nutrient policies should also reduce rates of diabetes, common cancers and childhood obesity. Furthermore, we only quantified averted deaths; proportional reductions in non-fatal conditions might reasonably be expected.36 Furthermore, several of our assumptions were tested by means of sensitivity analyses.

Unlike colleagues in the Netherlands and US, we did not model the effect of increasing the intake of nuts, whole grains, sugars, fish or marine omega-3 fatty acids.23,36,37 Promoting United Kingdom fish consumption might pose problems of affordability and sustainability.42 However, even using a complex Markov model, the Dutch results were reassuringly similar: an estimated 21% reduction in cardiovascular events versus our 20%.36 Our calculations only quantified deaths from CVD. Including common cancers might inflate benefits by another fifth, mainly through increased fruit and vegetable intake.3

In conclusion, stricter United Kingdom food policies could substantially and rapidly reduce cardiovascular mortality. Over the past decade, the United Kingdom Government and FSA’s voluntary agreements and partnership with industry have resulted in modest dietary improvements.43 However, the current United Kingdom dietary targets are clearly insufficient longer term. Cosy voluntary agreements with the processed food industry generally fail, much like tobacco policies in previous decades.32,44–46 Conversely, countries with healthier food policies (e.g. Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) have seen larger drops in major CVD risk factors and correspondingly bigger mortality reductions.8,43,44,47 However, setting tougher United Kingdom dietary targets will require additional regulatory, legislative and fiscal initiatives: evidence-based policy interventions recommended by the British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the World Health Organization (WHO), The World Bank and the United Nations.37 Indeed, both adults and children deserve better protection from the detrimental effects of cheap junk food and sugary drinks.32,40,41,45,46,48,49And a simple first step could be to eliminate industrial trans fats, as done successfully in Denmark and elsewhere.13

Funding:

MOF received funding from the UK Medical Research Council and from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n°223075 – the MedCHAMPS project. No funding body had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests:

SC was the vice-chair of the NICE PDG on CVD prevention in populations (2009–2010), and is a member of the British Heart Foundation (BHF) prevention and care committee. However, our recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of NICE or the BHF.

References

- 1.UK National Statistics [Internet]. London: Office for National Statistics; 2012. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE [accessed 4 March 2012].

- 2.Strategy Unit. Food matters: towards a strategy for the 21st century. London: The Cabinet Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarborough P, Nnoaham K, Clarke D, Rayner M. Differences in coronary heart disease, stroke and cancer mortality rates between England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: the role of diet and nutrition. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000263. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu FB. Globalization of food patterns and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2008;118:1913–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food Standards Agency [Internet]. Saturated fats. London: FSA; 2012. Available from: http://collections.europarchive.org/tna/20100927130941/http://food.gov.uk/healthiereating/satfatenergy/ [accessed 4 March 2012].

- 6.Bates B, Lennox A, Swan G, editors. National Diet Nutrition Survey: headline results for year 1 of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009) London: Food Standards Agency; 2009. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/publication/ndnsreport0809.pdf [accessed 24 February 2012].

- 7.He FJ, MacGregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:363–84. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laatikainen T, Critchley J, Vartiainen E, Salomaa V, Ketonen M, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in Finland between 1982 and 1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:764–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appel LJ, OmniHeart Collaborative Research Group Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids. JAMA. 2005;294:2455–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mozaffarian D, Stampfer MJ. Removing industrial trans fat from foods. BMJ. 2010;340:c1826. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food Standards Agency [Internet]. Safer food, better business. Trans fats. London: FSA; 2012. Available from. http://www.food.gov.uk/healthiereating/satfatenergy/transfat [accessed 24 February 2012].

- 12.Lloyd S, Madelin T, Caraher M. Chicken, chips and pizza: fast food outlets in Tower Hamlets report. London: Centre for Food Policy, City University London; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stender S, Dyerberg J, Bysted A, Leth T, Astrup A. A trans world journey. Atheroscler Suppl. 2006;7:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M. The burden of cardiovascular disease and cancer attributable to low fruit and vegetable intake in the European Union: differences between old and new Member States. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:575–83. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mozaffarian D, Aro A, Willett W. Health effects of trans-fatty acids: experimental and observational evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:S5–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Kandala N, Cappuccio F. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr. 2006;136:2588–93. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Neurology. 2005;65:1193–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180600.09719.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies Collaboration Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow G, Coxson P, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. Stroke. 2010;13:14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danaei G, Ding E, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murrray CJ, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith-Spangler CM, Juusola JL, Enns EA, Owens DK, Garber AM. Population strategies to decrease sodium intake and the burden of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:481–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence [Internet]. Prevention of cardiovascular disease at population level. London: NICE; 2010. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH25 [accessed 4 March 2012].

- 26.Barton P, Andronis L, Briggs A, McPherson K, Capewell S. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cardiovascular disease prevention in whole populations: modelling study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4044. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Europa: gateway to the European Union [Internet]. Policy Areas: Agriculture. Brussels: European Union; 2010. Available from: http://europa.eu/pol/agr/index_en.htm [accessed 24 February 2012].

- 28.Health Canada [Internet]. Trans Fat Monitoring Program. Ottawa: HC; 2009. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/gras-trans-fats/tfa-age_tc-tm-intro-eng.php [accessed 4 March 2012].

- 29.Public Health – Seattle and King County [Internet]. Artificial trans fat. Seattle: King County government; 2010. Available from: http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/nutrition/healthyeating/transfat.aspx [accessed 24 February 2012].

- 30.Food Standards Agency [Internet]. Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey. London: FSA; 2010. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk/science/dietarysurveys/lidnsbranch/ [accessed 24 February 2012].

- 31.Moreno LA, HELENA Study Group Assessing, understanding and modifying nutritional status, eating habits and physical activity in European adolescents: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:288–99. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brownell KD, Warner K. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died: How similar is big food? Milbank Q. 2009;87:259–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:100–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lloyd-Williams F, O’Flaherty M, Mwatsama M, Birt C, Ireland R, Capewell S. Estimating the cardiovascular mortality burden attributable to the European Common Agricultural Policy on dietary saturated fats. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:535–41A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barendregt JJ, Veerman JL. Categorical versus continuous risk factors and the calculation of potential fractions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:209–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelfriet P, Hoekstra J, Hoogenveen R, Büchner F, van Rossum C, Verschuren M. Food and vessels: the importance of a healthy diet to prevent cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:50–5. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832f3a76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mozaffarian D, Capewell S. United Nations dietary policies to prevent cardiovascular disease. Modest diet changes could halve the global burden. BMJ. 2011;343:d5747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capewell S, O’Flaherty M. Rapid mortality falls after risk factor changes in populations. Lancet. 2011;378:752–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zatonski WA, Willett W. Changes in dietary fat and declining coronary heart disease in Poland: population based study. BMJ. 2005;331:187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7510.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilmore AB, Savell E, Collin J. Public health, corporations and the new responsibility deal: promoting partnerships with vectors of disease? J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:2–4. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen D. Non communicable diseases: Will industry influence derail UN summit? BMJ. 2011;343:d5328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner EJ, Jones P, Friel S, Bartley M. Fish, human health and marine ecosystem health: policies in collision. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:93–100. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scholes S, Bajekal M, Raine R, O'Flaherty M, Capewell S. Socio-economic trends in cardiovascular risk factors in England, 1994–2008. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:A13. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.120956.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Magnusdottir BT, et al. Why have coronary heart disease mortality rates in Iceland plummeted between 1981 and 2006? Circulation. 2009;119:e348. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koplan JP, Brownell KD. Response of the food and beverage industry to the obesity threat. JAMA. 2010;304:1487–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evaluation of the European Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health London: The Evaluation Partnership; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Björck L, Rosengren A, Bennett K, Lappas G, Capewell S. Modelling the decreasing coronary heart disease mortality in Sweden between 1986 and 2002. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1046–56. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swinburn B, Sacks G, Lobstein T. The ‘Sydney principles’ for reducing the commercial promotion of foods and beverages to children. Public Health Nutr. 2007;11:881–6. doi: 10.1017/S136898000800284X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capewell S, Graham H. Will cardiovascular disease prevention widen health inequalities? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]