Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in low- and middle-income countries and identify factors associated with successful outcomes.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of HCV treatment programmes in low- and middle-income countries. The primary outcome was a sustained virological response (SVR). Factors associated with treatment outcomes were identified by random-effects meta-regression analysis.

Findings

The analysis involved data on 12 213 patients included in 93 studies from 17 countries. The overall SVR rate was 52% (95% confidence interval, CI: 48–56). For studies in which patients were predominantly infected with genotype 1 or 4 HCV, the pooled SVR rate was 49% (95% CI: 43–55). This was significantly lower than the rate of 59% (95% CI: 54–64) found in studies in which patients were predominantly infected with other genotypes (P = 0.012). Factors associated with successful outcomes included treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, infection with an HCV genotype other than genotype 1 or 4 and the absence of liver damage or human immunodeficiency virus infection at baseline. No significant difference in the SVR rate was observed between weight-adjusted and fixed-dose ribavirin treatment. Overall, 17% (95% CI: 13–23) of adverse events resulted in treatment interruption or dose modification, but only 4% (95% CI: 3–5) resulted in treatment discontinuation.

Conclusion

The outcomes of treatment for HCV infection in low- and middle-income countries were similar to those reported in high-income countries.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l’efficacité du traitement de l’infection par le virus de l’hépatite C (VHC) dans les pays à revenu faible et moyen et identifier les facteurs associés aux résultats positifs.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué une évaluation systématique et une méta-analyse des études sur les programmes de traitement du VHC dans les pays à revenu faible et moyen. Le résultat principal consistait en une réponse virologique soutenue (RVS). Les facteurs liés aux résultats du traitement ont été identifiés à l'aide d'une analyse de méta-régression des effets aléatoires.

Résultats

L'analyse portait sur les données de 12 213 patients inclus dans 93 études provenant de 17 pays différents. Le taux de RVS général était de 52% (intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC: 48-56). Pour les études dans lesquelles les patients étaient principalement atteints par le VHC de génotype 1 ou 4, le taux de RVS groupé était de 49% (IC de 95%: 43-55). Ce taux était largement inférieur à celui de 59% (IC de 95%: 54-64) présenté dans les études dans lesquelles les patients étaient principalement atteints par d'autres génotypes (P = 0,012). Les facteurs liés aux résultats positifs incluaient le traitement à l'interféron pégylé et à la ribavirine, l'infection à un VHC de génotype autre que 1 ou 4 et l'absence de lésions au foie ou d'infection par le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine initialement. Aucune différence significative dans le taux de RVS n'a été observée entre les traitements de ribavirine adaptés au poids et ceux à dose fixe. Dans l'ensemble, 17% (IC de 95%: 13-23) des effets indésirables ont entraîné une interruption du traitement ou une modification des doses, tandis que 4% (IC de 95%: 3-5) d'entre eux ont entraîné un abandon du traitement.

Conclusion

Les résultats du traitement de l’infection du VHC dans les pays à revenu faible et moyen étaient similaires à ceux qui étaient indiqués dans les pays à revenu élevé.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar la efectividad del tratamiento para la infección por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en países de ingresos medios y bajos e identificar los factores asociados con unos resultados satisfactorios.

Métodos

Realizamos un examen sistemático y un meta-análisis de estudios de programas de tratamiento del VHC en países de ingresos medios y bajos. El resultado fundamental fue una respuesta viral sostenida (RVS). Los factores asociados con los resultados del tratamiento se identificaron mediante un análisis de metarregresión de efectos aleatorios.

Resultados

El análisis incluyó datos sobre 12 213 pacientes en 93 estudios de 17 países. La tasa global de RVS fue del 52% (intervalo de confianza, IC del 95%: 48–56). Para estudios en los que los pacientes estaban predominantemente infectados con VHC del genotipo 1 o 4, la tasa de RVS combinada fue del 49% (IC del 95%: 43–55). Esta fue significativamente menor que la tasa del 59% (IC del 95%: 54–64) encontrada en estudios en los que los pacientes estaban predominantemente infectados con otros genotipos (P = 0,012). Los factores asociados con los resultados satisfactorios incluyeron el tratamiento con interferón pegilado y ribavirina, la infección del VHC de un genotipo distinto al 1 o al 4 y la ausencia de lesión hepática o de infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana en el inicio. No se observaron diferencias significativas en la tasa de RVS entre el tratamiento de ribavirina adaptado al peso del paciente y el de dosis fijas. En conjunto, el 17% (IC del 95%: 13–23) de los eventos adversos provocó la interrupción del tratamiento o la modificación de la dosis, mientras que el 4% (IC del 95%: 3–5) causó el abandono del tratamiento.

Conclusión

Los resultados del tratamiento de la infección del VHC en países de ingresos bajos y medios fueron similares a los de países de ingresos elevados.

ملخص

الغرض

تقييم فعالية علاج عدوى فيروس التهاب الكبد C (HCV) في البلدان منخفضة ومتوسطة الدخل وتحديد العوامل المرتبطة بالنتائج الناجحة.

الطريقة

أجرينا استعراضاً منهجياً وتحليلاً وصفياً لدراسات برامج علاج فيروس التهاب الكبد C في البلدان منخفضة ومتوسطة الدخل. وكانت النتيجة الأولية استجابة فيروسية مستديمة (SVR). وتم تحديد العوامل المرتبطة بنتائج العلاج من خلال تحليل الارتداد الوصفي للآثار العشوائية.

النتائج

اشتمل التحليل على بيانات حول 12213 مريضًا تم إدراجهم في 93 دراسة من 17 بلدًا. وكان المعدل الكلي للاستجابة الفيروسية المستديمة 52 % (95 %، فاصل الثقة: 48-56). وبخصوص الدراسات التي ضمت مرضى مصابين بشكل عام بعدوى فيروس التهاب كبد C بالنمط الجيني 1 أو 4، كان المعدل المجمع للاستجابة الفيروسية المستديمة 49 % (95 %، فاصل الثقة: 43-55). وكان هذا المعدل منخفضاً بدرجة كبيرة عن معدل 59 % (95 %، فاصل الثقة: 54-64) الموجود في الدراسات التي ضمت مرضى مصابين بشكل عام بعدوى الأنماط الجينية الأخرى (الاحتمال = 0.012). و تضمنت العوامل المرتبطة بالنتائج الناجحة العلاج بالإنترفيرون والريبافيرين مديدي المفعول، والعدوى بالنمط الجيني لفيروس التهاب الكبد C من غير النمط الجيني 1 أو 4 وعدم تلف الكبد أو عدم وجود عدوى فيروس العوز المناعي البشري عند خط الأساس. ولم تتم ملاحظة اختلاف مؤثر في معدل الاستجابة الفيروسية المستديمة بين العلاج بالريبافيرين المعدل حسب الوزن وبين العلاج ثابت الجرعة. وبشكل عام، نتجت نسبة 17 % (95 %، فاصل الثقة: 13-23) من الأحداث الضائرة عن قطع العلاج أو تعديل الجرعة بينما نتجت نسبة 4 % (95 %، فاصل الثقة: 3-5) من هذه الأحداث عن إيقاف العلاج.

الاستنتاج

كانت نتائج علاج عدوى فيروس التهاب الكبد C في البلدان منخفضة ومتوسطة الدخل متشابهة مع تلك المبلغ عنها في البلدان مرتفعة الدخل.

摘要

目的

评估中低收入国家治疗丙型肝炎病毒(HCV)感染的效果并确定成功结果的相关因素。

方法

我们对中低收入国家的丙型肝炎病毒治疗方案研究进行了系统性回顾和元分析。主要成果是治疗持续病毒学响应(SVR)。随机效应元回归分析确定与治疗效果相关的因素。

结果

分析来自17 个国家93 个研究中涉及12213 例病患的数据。总体SVR率为52%(95%置信区间,CI:48-56)。对于患者主要感染基因型1 或4 丙型肝炎病毒的研究,合并的SVR率为49%(95% CI:43-55);在患者主要感染其他基因型病毒(p =0.012)的研究中发现的SVR率为59%(95% CI:54-64),前者比率显著低于后者。与成功结果关联的因素包括使用聚乙二醇干扰素和利巴韦林治疗、感染非基因型1 或4 的基因型丙型肝炎病毒、无肝损害或者基线艾滋病毒感染。在权重调整和固定剂量的利巴韦林治疗之间未观察到SVR率的显著差异。总体而言,17%(95% CI:13-23)的不良事件导致治疗间断或剂量调整,而 4%(95% CI:3-5)的不良事件导致治疗终止。

结论

中低收入国家丙型肝炎病毒感染治疗的效果与高收入国家报道的效果相似。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить эффективность лечения вируса гепатита С (ВГС) в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода, а также определить факторы, влияющие на достижение успешных результатов.

Методы

Мы провели систематический обзор и мета-анализ исследований, посвященных программам лечения ВГC в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода. В качестве основного параметра оценки было выбранополучение устойчивого вирусологического ответа (УВО). Факторы, связанные с результатами лечения, идентифицировались с помощью мета-регрессионного анализа на основе модели случайных эффектов.

Результаты

Были проанализированы данные о 12 213 пациентах, участвовавших в 93 исследованиях в 17 странах. Общий уровень УВО составил 52% (доверительный интервал, ДИ 95%: 48–56). Для исследований, в которых пациенты были инфицированы преимущественно ВГС с генотипом 1 или 4, агрегированное значение УВО составило 49% (ДИ 95%: 43–55). Это было значительно ниже уровня 59% (ДИ 95%: 54–64), выявленного в исследованиях, в которых пациенты были инфицированы преимущественно другими генотипами (P = 0,012). Факторы, влияющие на достижение успешных результатов, включали лечение пегилированным интерфероном и рибавирином, инфицирование генотипом, отличным от 1 и 4, а также отсутствие повреждения печени или вируса иммунодефицита человека на начальном этапе. Не наблюдалось каких-либо существенных различий в уровне УВО между дозировкой рибавирина в зависимости от массы тела и фиксированной дозировкой. В целом, 17% (ДИ 95%: 13–23) нежелательных реакций приводили к прерыванию лечения или изменению дозировки, а 4% (ДИ 95%: 3–5) – к прекращению лечения.

Вывод

Результаты лечения инфекции ВГС в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода были схожи с теми, о которых отчитываются в странах с высоким уровнем доходов.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a growing public health concern. Globally an estimated 180 million people, or roughly 3% of the world’s population, are currently infected.1 The burden of disease is greatest in developing countries: the highest reported prevalences are in China (3.2%), Egypt (22%) and Pakistan (4.8%).2

In light of the above, the need to improve access to care and treatment for patients with a chronic HCV infection is receiving increasing attention. A recent report by the World Hepatitis Alliance revealed that 80% of 135 countries surveyed regarded hepatitis B or C virus infection as an urgent public health issue.3 In 2010, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to “support or enable an integrated and cost-effective approach to the prevention, control and management of viral hepatitis considering the linkages with associated coinfection such as HIV”.4

Most of the disease burden associated with HCV infection results from the development of chronic liver disease, sometimes leading to end-stage liver disease (cirrhosis), and standardized mortality ratios for liver-related death are 16- to 46-fold higher in infected individuals than in the general population.5–7 The complications of cirrhosis include liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma and death.8,9 Approximately 20% of HCV-infected patients will experience complications.10–12 Successful treatment can improve liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, help prevent hepatocellular carcinoma and even clear the virus.13 Treatment can also contribute to disease prevention by reducing the reservoir of infected individuals who can transmit the virus.

Despite the benefits of treatment, there is reluctance to making it more widely available in resource-limited settings because of fears that treatment success rates will be low and because treatment is complex, costly and produces side-effects.14 In addition, outcomes are often poor in patients coinfected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).15

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of reported treatment outcomes in HCV-infected patients in low- and middle-income countries. The aims were to assess the feasibility of providing treatment for HCV infection in less well-resourced settings and to identify factors associated with successful treatment outcomes.

Methods

The PubMed and Embase databases were searched for articles on observational studies that reported sustained virological response (SVR) rates in adult patients with chronic HCV infection and that were performed in a low- or middle-income country, as defined by The World Bank classification.16 Both cohort studies and case series including 10 or more patients were considered for inclusion. An SVR was defined as the absence of detectable HCV in blood 24 weeks after the completion of antiviral therapy.

The databases were searched using a predefined protocol (Appendix A, available at: http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/HIV_AIDS/Docs/AIDS_MedJourn_HCVtreatmentReview_ENG_2011.pdf) using the terms hepatitis C, HCV, treatment, therapy, interferon, sustained virological response and SVR. In addition, the bibliographies of relevant articles were reviewed. Preliminary searches were carried out independently by two of the study authors, who decided whether a publication was eligible for inclusion in the systematic review by evaluating its title using predefined criteria. If there was any uncertainty, all the study authors were consulted to reach a consensus on eligibility.

Because the aim of the systematic review was to describe the outcomes of HCV treatment administered within a clinical programme, we included observational cohort studies that reported treatment outcomes and excluded studies with an experimental design. We also excluded studies that reported outcomes in specific patient groups, such as patients with comorbid conditions, with prior treatment, or with known treatment resistance. However, because of concerns about HCV infection in HIV-infected individuals, studies on patients coinfected with HIV were included in the review.

Data extraction

Our primary outcome of interest was the SVR rate. Secondary outcomes included end-of-treatment responses, adverse events resulting in treatment interruption, modification or discontinuation, the proportion of patients lost to follow-up, and mortality. A patient was defined as having an end-of-treatment response if HCV ribonucleic acid was undetectable at the completion of treatment.

Each cohort was divided into categories in accordance with the following discrete clinical variables: (i) whether standard or pegylated interferon was administered, irrespective of the type of interferon; (ii) whether fixed-dose or weight-adjusted ribavirin was administered; (iii) whether treatment lasted less than 24 weeks or longer; (iv) whether fewer than or more than 50% of patients in the study cohort were HIV-positive (HIV+); (v) whether fewer than or more than 50% of patients in the study cohort were infected with genotype 1 or 4 (these genotypes are associated with a poor response to treatment); and (vi) whether fewer than or more than 50% of patients in the study cohort had bridging fibrosis, an indicator of the extent of liver damage, at baseline. In addition, information was also sought on the presence of the interleukin-28B gene polymorphism, which is as an important determinant of treatment success.

The methodological quality of the studies included in the systematic review was assessed on the basis of the study design (i.e. retrospective or prospective), the reporting of disease status at baseline, the proportion of patients who completed treatment, and consideration of potential confounding. Finally, information on sources of funding were extracted to give an indication of the potential replicability and sustainability of the treatment programme. Any uncertainty surrounding the data was resolved by contacting the study authors.

Statistical analysis

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived for all outcomes. The SVR rates were calculated on an intention-to-treat basis, with all patients who initiated therapy being included in the denominator of the calculation. The variance in the raw proportion was stabilized using a Freeman–Tukey-type arcsine square-root transformation17 and these proportions were pooled using a DerSimonian–Laird random-effects model.18 The τ2 statistic was calculated to assess the proportion of the overall variation that was attributable to between-study heterogeneity.19,20 Since pooling proportions can yield high rates of heterogeneity, we explored the potential influence of clinical and programmatic covariates that had been identified a priori through random-effects method-of-moments meta-regression21 and univariate subgroup analyses. Subgroup analyses were used to assess the potential influence of the following covariates: treatment regimen, HIV status, HCV genotype, liver damage at baseline, level of economic development of the study region, geographical location of the study region and study design (i.e. prospective or retrospective). All reported P-values are two-sided and significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 11 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America).

Results

Study characteristics

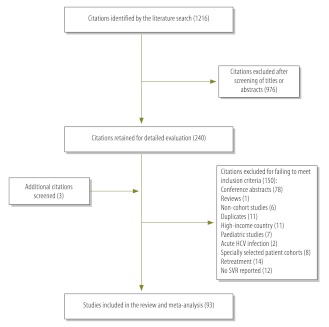

Our search found 1216 articles. After evaluation, 93 studies, which involved a total of 12 213 patients, met our inclusion criteria and were carried through to the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Although the studies covered 17 countries, some were more frequently represented: there were 19 studies from Brazil, 17 from Pakistan, 13 from Egypt, 12 from China and 10 from India.

Fig. 1.

Selection of studies on chronic hepatitis C treatment in low- and middle-income countries

HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virological response.

Around half of the studies (i.e. 46 studies involving 5995 patients) included patients who were predominantly infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4. Ten studies failed to adequately report on viral genotype. Patients were treated with ribavirin and interferon in 86 studies, while interferon alone was given in 7 studies: pegylated interferon was administered in 52 and standard interferon was used in 44. The extent of liver damage at baseline was reported in 33 studies, together comprising 2407 patients. In addition, although 54 studies gave details of patients’ HIV status, only 3, which included 105 patients in total, reported outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Two studies included data on outcomes in patients with and without the interleukin-28B gene polymorphism.

We judged the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis to be moderate. The majority (i.e. 65 studies) reported prospectively collected data, 72 detailed disease progression at baseline, 77 considered potential confounding factors and 89 stated that ≥ 80% of patients completed treatment.

Of the 29 studies that reported sources of funding, 18 were supported by national government funds, 4 received pharmaceutical industry funding, 1 was supported by an international research grant, 1 by a charitable grant and 5 stated that the study received no specific funding. A table summarizing each study’s characteristics is available in Appendix B, at: http://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/CAME/Access_Data_StudyCharacteristics_ENG_2012.pdf.

Study outcomes

Overall, 52% (95% CI: 48–56) of patients achieved an SVR. However, the between-study heterogeneity in the SVR rate was high (τ2: 410), as expected for observational data. For studies in which patients were predominantly infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4, the proportion of patients who achieved an SVR ranged from 4% (95% CI: 1–9)22 to 79% (95% CI: 66–89)23 and the pooled proportion was 49% (95% CI: 43–55). For studies in which patients were predominantly infected with HCV genotypes other than 1 or 4, the SVR rate ranged from 16% (95% CI: 10–24)24 to 86% (95% CI: 77–93)25 and the pooled proportion of these patients who achieved an SVR was 59% (95% CI: 54–64), which was significantly higher than among patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 (P = 0.012). Since the treatment duration was found to be collinear with viral genotype, it was not considered in the analysis.

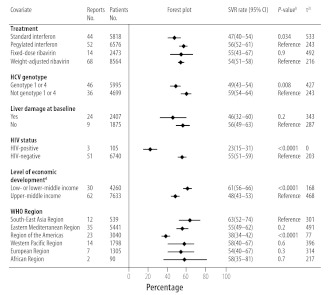

Fig. 2 summarizes how the SVR rate was influenced by HCV treatment, viral genotype, liver damage at baseline, HIV status, the level of economic development and the geographical location of the study region. Univariate meta-regression analysis showed that the proportion of patients who achieved an SVR varied significantly with the formulation of the interferon administered (i.e. standard or pegylated), ribavirin use, viral genotype, the severity of liver damage at baseline, HIV status and the level of economic development of the study region (Table 1). Viral genotype and HIV status were still found to be significantly associated with the SVR rate on multivariate analysis, but other factors were not. Further, subgroup analyses showed that the best outcomes were achieved in studies in which patients were either predominantly HIV-negative (HIV−), predominantly infected with an HCV genotype other than 1 or 4, or treated with ribavirin. The proportion of patients who achieved an SVR in the 20 studies that included patients with all three of these characteristics ranged from 45% (95% CI: 34–55)70 to 78% (95% CI: 61–91)71 and the pooled proportion was 65% (95% CI: 61–68). The presence of the interleukin-28B polymorphism was associated with a high SVR rate in the two studies which reported relevant data.26,72

Fig. 2.

Sustained virological responsea rate in patients with a chronic hepatitis C virus infection in low- and middle-income countries, by treatment, disease, patient and study covariates

CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virological response; WHO, World Health Organization.

a A sustained virological response was defined as the absence of detectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) in blood 24 weeks after the completion of antiviral therapy.

b P-values were derived using the χ2 test for the difference between reference and comparison groups.

c The Tau-squared (τ2) statistic indicates the degree to which the overall variation in the sustained virological response rate was attributable to between-study heterogeneity.

d The level of economic development of the study country was categorized using the World Bank classification.16

Table 1. Effect of treatment, disease, patient and study covariates on the sustained virological responsea rate in patients with a chronic hepatitis C virus infection in low- and middle-income countries, by meta-regression analysis.

| Covariate | No. of reportsb | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | β coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Treatment regimen | ||||||

| Standard interferon22,24,26–69 | 44 | −10.6 (−18.0 to −3.1) | 0.006 | −7.8 (−16.6 to 0.9) | 0.07 | |

| Pegylated interferon25,26,29,33,36,38,61,63,65,67,70–115 | 52 | Reference | NA | Reference | NA | |

| Ribavirin not administered22,37,40,50,56,64,85 | 7 | 27.5 (13.8 to 41.2) | < 0.0001 | 1.6 (−21.8 to 18.6) | 0.9 | |

| Ribavirin administered24–36,38,39,41–49,51,53–55,57–63,66–84,86–93,95–100,102–115 | 86 | Reference | NA | Reference | NA | |

| Fixed-dose ribavirin24,26,31,45,46,58,60,66,69,71,80,82,84,97 | 14 | 1.2 (−8.5 to 10.9) | 0.8 | ND | ND | |

| Weight-based ribavirin25,27–30,32,33,35,36,38,39,41,42,44,47–49,51–55,57,59,61–63,65,67,68,72–79,81,83,86–93,95,96,98–115 | 68 | Reference | NA | ND | ND | |

| HCV genotype | ||||||

| Genotype 1 or 422,26,34,37–39,54–57,63,65,67–69,72,73,76–83,85,86,88,90–94,96,97,100–107,109–111,114,115 | 46 | −10.2 (−17.7 to −2.5) | 0.01 | −11.9 (−23.8 to 0) | 0.005 | |

| Not genotype 1 or 424,25,27–29,32,33,35,36,41–47,50–53,58,62,66,70,71,74,75,84,87,89,95,108,110,112,113 | 36 | Reference | NA | Reference | NA | |

| Liver damage at baseline | ||||||

| Yes33,34,36,54,55,57,58,63,65–67,69,70,75,76,79,87,88,90,92,93,95,101,104,105,115 | 24 | −12.2 (−23.2 to −1.3) | 0.03 | ND | ND | |

| No26,51,64,78,98–100,108,110 | 9 | Reference | NA | ND | ND | |

| HIV status | ||||||

| HIV-positive73,76,104 | 3 | −32.4 (−50.5 to −14.2) | 0.001 | −28.9 (−45.9 to −11.9) | 0.001 | |

| HIV-negative27,28,31,32,34–36,39,41,43,44,46,50–52,54,55,58,63,65,67–73,75,76,78,80,82,83,85–87,89–96,98–100,102,104–106,108,111–115 | 51 | Reference | NA | Reference | NA | |

| Economic level of study regionc | ||||||

| Low- or lower-middle income25,27–33,36,41–43,45–48,51–53,58,62,66,71,74,75,84,87,89,105,108 | 30 | −13.0 (−20.7 to −5.2) | 0.001 | −6.7 (−19.4 to 6.0) | 0.3 | |

| Upper-middle income22,24,26,34,35,37–40,44,49,50,53–57,59–61,63–65,67–70,72,73,76–83,85,86,88,90–93,95–104,106,107,109–115 | 62 | Reference | NA | Reference | NA | |

| Study design | ||||||

| Prospective22,24,25,28–32,34,35,37–39,41,43–45,47–52,55,57,58,62,66,69–75,77–80,82,84–86,88,90–93,95–102,104,105,107,108,110–112,115 | 65 | −2.6 (−11 to 5.7) | 0.5 | ND | ND | |

| Retrospective26,27,33,36,40,42,46,52,54,56,59–61,63–65,67,68,76,81,83,87,89,103,106,109,113,114 | 28 | Reference | NA | ND | ND | |

CI, confidence interval; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

a A sustained virological response was defined as the absence of detectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) in blood 24 weeks after the completion of antiviral therapy.

b Since one publication77 reported one study fully and gave the preliminary outcomes of a second study, the figures here could differ by 1 from those in the text.

c The level of economic development of the study country was categorized using The World Bank classification.16

End-of-treatment responses were recorded in 49 studies. The pooled estimate of the proportion of patients who achieved an end-of-treatment response was higher: (i) for those who were HIV− than for those who were HIV+, at 74% versus 52%, respectively; (ii) for those who received ribavirin than for those who did not, at 69% versus 51%, respectively; and (iii) for those who received pegylated rather than standard interferon, at 73% versus 62%, respectively. Overall, 53% (95% CI: 47–58) of patients who achieved an end-of-treatment response went on to achieve an SVR. This rate was significantly greater in patients who were treated with pegylated interferon (i.e. 57%; 95% CI: 52–63) than in those who received standard interferon (i.e. 47%; 95% CI: 38–56) and in those who were HIV− (i.e. 59%; 95% CI: 53–64) than in those who were HIV+ (i.e. 35%; 95% CI: 30–40). However, neither viral genotype (P = 0.2), ribavirin treatment (P = 0.6) nor liver damage at baseline (P = 0.4) influenced the proportion that went on to achieve an SVR.

Adverse events that resulted in treatment interruption or dose modification were reported in 16 studies and were experienced by 17% (95%CI: 13–23) of patients in these studies. The drug regimen had no significant effect on the proportion of these adverse events. Adverse events that resulted in treatment termination were reported in 39 studies and were experienced by 4% of patients (95% CI: 3–5). These adverse events were significantly more common in patients who were taking weight-adjusted ribavirin than in those taking fixed-dose ribavirin (4% versus 2%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Table 2 lists the most serious adverse events that led to treatment discontinuation in individual studies.

Table 2. Serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation in patients with a chronic hepatitis C virus infection in low- and middle-income countries, 1996–2011.

| Publication | Year | Country | No. of patients affected | Type of event (No. of patients affected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sood58 | 2002 | India | 3 | Psychiatric illness (2), hypotension (1) |

| Sood87 | 2006 | India | 3 | Agitated behaviour (1), liver decompensation (2) |

| Gupta71 | 2006 | India | 1 | Weakness (1) |

| Ahmed27 | 2011 | Pakistan | 14 | Thrombocytopenia, ascites, depression, arthralgia, weight loss, rash, fever, hair loss, epistaxisa |

| Khan46 | 2009 | Pakistan | 12 | Extreme weakness (6), severe depression (2), thyroid dysfunction (3), recurrent leukopenia (1) |

| Khokhar47 | 2002 | Pakistan | 2 | Myalgia (1), psychosis (1) |

| Khalid45 | 2009 | Pakistan | 1 | Severe depression (1) |

| Idrees42 | 2009 | Pakistan | 6 | Psychosis (6) |

| Butt75 | 2009 | Pakistan | 5 | Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia (2), refractory anaemia (2), ascites and hepatic encephalopathy (1) |

| Lerias de Almeida76 | 2009 | Brazil | 33 | Not stated |

| Lerias de Almeida90 | 2010 | Brazil | 7 | Not stated |

| Goncales78 | 2006 | Brazil | 10 | Depression (6), neutropenia (2), anaemia (1), low platelet count (1) |

| Narciso-Schiavon81 | 2010 | Brazil | 22 | Anaemia (2), thrombocytopenia (2), not stated (18) |

| Khattab91 | 2010 | Egypt | 4 | Not stated |

| El Makhzangy92 | 2009 | Egypt | 2 | Psychiatric disorder (1), haemolytic anaemia (1) |

| El-Zayadi22 | 1996 | Egypt | 8 | Not stated |

| El-Zayadi38 | 2005 | Egypt | 4 | Neutropenia (1), thyroid dysfunction (1), depression (1), neutropenia (1) |

| Yu111 | 2009 | China | 1 | Severe anaemia (1) |

| Gheorghe100 | 2007 | Romania | 11 | Severe psychiatric side-effects, severe haematological abnormalities, severe reactivation of previously controlled rheumatoid arthritis, cardiac deatha |

| Gheorghe99 | 2009 | Romania | 20 | Severe psychiatric side-effects (2), severe haematological abnormalities (9), occurrence or reactivation of auto-immune disease during antiviral therapy (7), cardiac death (1), not stated (1) |

| Gheorghe98 | 2005 | Romania | 10 | Severe haematological abnormalities, severe and protracted skin rash, acute cytomegalovirus hepatitisa |

| Gallegos-Orozco39 | 2005 | Mexico | 1 | Thyrotoxicosis (1) |

| Ridruejo106 | 2010 | Argentina | 18 | Not stated |

| Laufer104 | 2011 | Argentina | 2 | Thrombocytopenia (2) |

| Seow107 | 2005 | Malaysia | 1 | Excessive lethargy (1) |

| Pramoolsinsap50 | 1998 | Thailand | 3 | Thrombocytopenia (2), hyperthyroidism (1) |

| Kalantari44 | 2007 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 2 | Thrombocytopenia (1), major depression (1) |

| Petrenkiene49 | 2004 | Lithuania | 11 | Anaemia (1), thrombocytopenia (5), irritability (1), exacerbation of concomitant disease (1), not stated (3) |

| Belhadj95 | 2008 | Tunisia | 5 | Not stated |

| Sombie108 | 2011 | Burkina Faso | 2 | Not stated |

| Njoum105 | 2008 | Cameroon | 6 | Neutropenia, encephalitis, pancytopenia and thrombopeniaa |

a Detailed data were not available.

Overall, 39 studies reported losses to follow-up. The rate was generally low and the pooled proportion of patients reported as lost to follow-up was 4% (95% CI: 3–4). In addition, mortality was also low: less than 1% (95% CI: 0.1–1) of patients were reported to have died during the observation period.

Discussion

Our systematic review found many reports of HCV treatment programmes in low- and middle-income countries involving substantial numbers of patients. They indicated that the programmes had been successful. Notably, most of the studies that gave information on funding sources reported funding from domestic public sources. This observation is consistent with recent survey data indicating that partial or total government funding is available for hepatitis treatment in 69% of countries worldwide and in more than 50% of countries in all WHO regions except the WHO African Region.3 We found that overall 52% of patients treated in low- and middle-income countries achieved an SVR, which is similar to the rate reported in high-income countries. For example, in developed countries, the average SVR rate observed in clinical trials of patients with HCV genotype 1 infections after 48 weeks of treatment with pegylated interferon and weight-adjusted ribavirin ranged from 45% to 48%, while it ranged from 22% to 31% after 24 weeks of treatment.116

As found in other studies, the most important determinants of treatment success were infection with an HCV genotype other than 1 or 4, the absence of liver damage at baseline, an HIV− status and treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.116 The geographical variations in outcomes we observed were probably due to a combination of these factors. Although, as expected, treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin was associated with better outcomes than treatment with other regimens, the use of weight-adjusted rather than fixed-dose ribavirin offered no observable advantage. Moreover, despite reports that HCV treatment is associated with significant side-effects, only 4% of patients included in our meta-analysis discontinued treatment because of adverse events. The observation that clinical rather than geographical factors were the most important determinants of treatment success suggests that good outcomes can be achieved with current regimens in resource-limited settings and offers support to calls for better access to diagnosis and treatment in these settings.117

We used a broad search strategy that attempted to capture evidence from many different settings. Consequently, we were able to compile a large meta-analytical data set that enabled us to assess the influence on treatment success of numerous patient, treatment and disease characteristics. However, the way in which studies reported information on potential determinants of treatment success was inconsistent and limited our ability to assess their relative contributions. For example, although we identified a substantial number of studies from countries with a relatively high burden of both HIV and HCV infection, only three reported outcomes among patients coinfected with the two viruses. In addition, few data were available on adherence to treatment, another important determinant of treatment success. The influence of the interleukin-28B gene polymorphism, which is also known to affect responses to treatment, was also poorly reported, probably because of limited resources. Future studies should report data on factors known to influence outcomes, particularly those in underrepresented regions, notably Africa, and in underrepresented populations, notably HIV+ patients and people who inject drugs.

Furthermore, the substantial heterogeneity in results we observed between studies limited the validity of this analysis, as it made it more difficult to determine the magnitude of the relative influence of individual factors on treatment success. In addition, we may have missed some studies because we searched a limited number of databases and our review excluded studies that reported outcomes in patients who were coinfected with a non-HIV agent that may have influenced treatment outcomes, such as the hepatitis B virus. Finally, our analysis was also limited by inconsistent reporting of secondary outcomes. Future studies should report rapid virological responses, end-of-treatment responses, adverse events and losses to follow-up. Data on rapid virological responses would help inform decisions on whether to shorten treatment.114

Given these limitations, our review should not be taken as representative of all low- and middle-income countries. It does, however, illustrate the range of treatment outcomes that can be achieved in settings with limited resources.

With currently available regimens, the treatment success rate achievable in patients infected with an HCV genotype other than 1 and 4 is in line with or better than the success rate achieved with other chronic infections that cause substantial morbidity in resource-limited settings, such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.118 However, currently the cost of treatment is a major barrier: a 48-week course of pegylated interferon and ribavirin costs as much in Thailand as in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (i.e. around 17 000 United States dollars). Treatment with recently approved protease inhibitors substantially improves success rates and these drugs are now the standard of care for patients with HCV genotype 1 infections in resource-rich settings, but they are even more expensive.119 In a recent survey in low-income countries, four out of five ministries of health identified the need for financial assistance to increase access to treatment for viral hepatitis as a priority.3 Future research on barriers to obtaining medicines for the treatment of HCV infection in resource-limited settings should be encouraged.

New protease and polymerase inhibitors currently under investigation offer the potential for oral therapy that will further improve the SVR rate in patients with HCV infection and may also reduce both treatment complexity and adverse events.120 These drugs will be particularly useful in resource-limited settings where the disease burden is greatest. Given that HCV treatment can be successful in these settings, the early introduction of new therapies in countries with limited resources should be an important consideration during drug development. In the past, mechanisms for decreasing the cost of and improving access to medicines for chronic infections such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS have been established; similar mechanisms should be considered for HCV infection.

In summary, our review found that patients with an HCV infection in resource-limited settings have treatment success rates similar to those in developed countries. This observation provides further justification for increasing efforts to improve access to HCV treatment in low- and middle-income countries.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Hadigan C, Kottilil S. Hepatitis C virus infection and coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus: challenges and advancements in management. JAMA. 2011;306:294–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–67. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viral hepatitis: global policy London: World Hepatitis Alliance; 2011. Available from: http://www.worldhepatitisalliance.org/Policy/2010PolicyReport.aspxhttp://[accessed 12 January 2012].

- 4.Viral hepatitis. WHA63.18. Sixty-third World Health Assembly. Agenda item 11.12. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R18-en.pdfhttp://[accessed 12 January 2012].

- 5.Amin J, Law MG, Bartlett M, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Causes of death after diagnosis of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection: a large community-based linkage study. Lancet. 2006;368:938–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duberg AS, Torner A, Davidsdottir L, Aleman S, Blaxhult A, Svensson A, et al. Cause of death in individuals with chronic HBV and/or HCV infection, a nationwide community-based register study. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:538–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, Mills PR, Dillon J, Bloor M, et al. A population-based record linkage study of mortality in hepatitis C-diagnosed persons with or without HIV coinfection in Scotland. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18:271–83. doi: 10.1177/0962280208094690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John-Baptiste A, Krahn M, Heathcote J, Laporte A, Tomlinson G. The natural history of hepatitis C infection acquired through injection drug use: meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Hepatol. 2010;53:245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massard J, Ratziu V, Thabut D, Moussalli J, Lebray P, Benhamou Y, et al. Natural history and predictors of disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl):S19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SL, Morgan TR. The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:47–52. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48:418–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.22375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearlman BL, Traub N. Sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cure and so much more. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:889–900. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper CL, Mills E, Wabwire BO, Ford N, Olupot-Olupot P. Chronic viral hepatitis may diminish the gains of HIV antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:302–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Operskalski EA, Kovacs A. HIV/HCV co-infection: pathogenesis, clinical complications, treatment, and new therapeutic technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:12–22. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0071-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Country and lending groups [Internet]. Washington: World Bank; 2011. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groupshttp://[accessed 12 January 2012].

- 17.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Inst Stat Math. 1950;21:607–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993;2:121–45. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters DE. The need for statistical rigour when pooling data from a variety of sources. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1205–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Meta-regression. In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, editors. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. pp.190–202. [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Zayadi A, Simmonds P, Dabbous H, Prescott L, Selim O, Ahdy A. Response to interferon-alpha of Egyptian patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 4. J Viral Hepat. 1996;3:261–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossignol JF, Elfert A, El-Gohary Y, Keeffe EB. Improved virologic response in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 treated with nitazoxanide, peginterferon, and ribavirin. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:856–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiao J, Wang JB. Hepatitis C virus genotypes, HLA-DRB alleles and their response to interferon-alpha and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra PK, Bhargava A, Khan S, Pathak N, Punde RP, Varshney S. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes and impact of T helper cytokines in achieving sustained virological response during combination therapy: a study from central India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28:358–62. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.71813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JY, Lin CY, Wang CM, Lin YT, Kuo SN, Shiu CF, et al. IL28B genetic variations are associated with high sustained virological response (SVR) of interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy in Taiwanese chronic HCV infection. Genes Immun. 2011;12:300–9. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed WU, Arif A, Qureshi H, Alam SE, Ather R, Fariha S, et al. Factors influencing the response of interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbar H, Idrees M, Butt S, Awan Z, Sabar MF, Rehaman IU, et al. High baseline interleukine-8 level is an independent risk factor for the achievement of sustained virological response in chronic HCV patients. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akram M, Idrees M, Zafar S, Hussain A, Butt S, Afzal S, et al. Effects of host and virus related factors on interferon-alpha+ribavirin and pegylated-interferon+ribavirin treatment outcomes in chronic hepatitis C patients. Virol J. 2011;8:234. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali I, Khan S, Attaullah S, Khan SN, Khan J, Siraj S, et al. Response to combination therapy of HCV 3a infected Pakistani patients and the role of NS5A protein. Virol J. 2011;8:258. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali L, Mansoor A, Ahmad N, Siddiqi S, Mazhar K, Muazzam AG, et al. Patient HLA-DRB1* and -DQB1* allele and haplotype association with hepatitis C virus persistence and clearance. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1931–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amarapurkar D, Dhorda M, Kirpalani A, Amarapurkar A, Kankonkar S. Prevalence of hepatitis C genotypes in Indian patients and their clinical significance. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:983–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antaki N, Hermes A, Hadad M, Ftayeh M, Antaki F, Abdo N, et al. Efficacy of interferon plus ribavirin in the treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 5. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:383–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouzgarrou N, Hassen E, Mahfoudh W, Gabbouj S, Schvoerer E, Ben Yahia A, et al. NS5A(ISDR-V3) region genetic variability of Tunisian HCV-1b strains: correlation with the response to the combined interferon/ribavirin therapy. J Med Virol. 2009;81:2021–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai CY, Chuang WL, Chang WY, Chen SC, Lee LP, Hsieh MY, et al. Co-infection of SENV-D among chronic hepatitis C patients treated with combination therapy with high-dose interferon-alfa and ribavirin. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4241–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i27.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.David J, Rajasekar A, Daniel HD, Ngui SL, Ramakrishna B, Zachariah UG, et al. Infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 – experience of a tertiary health care centre in south India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28:155–7. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.62495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Zayadi A, Selim O, Hamdy H, El-Tawil A, Badran HM, Attia M, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C Egyptian patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2963–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i20.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Zayadi AR, Attia M, Barakat EM, Badran HM, Hamdy H, El-Tawil A, et al. Response of hepatitis C genotype-4 naive patients to 24 weeks of peg-interferon-alpha2b/ribavirin or induction-dose interferon-alpha2b/ribavirin/amantadine: a non-randomized controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2447–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallegos-Orozco JF, Loaeza-del Castillo A, Fuentes AP, Garcia-Sandoval M, Soto L, Rodriguez R, et al. Early hepatitis C virus changes and sustained response in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin. Liver Int. 2005;25:91–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.1040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong GZ, Lai LY, Jiang YF, He Y, Su XS. HCV replication in PBMC and its influence on interferon therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:291–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hazari S, Panda SK, Gupta SD, Batra Y, Singh R, Acharya SK. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in patients of northern India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1058–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Idrees M, Riazuddin S. A study of best positive predictors for sustained virologic response to interferon alpha plus ribavirin therapy in naive chronic hepatitis C patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iqbal SKU-R, Dogar MZ, Bashir S, Akhtar M. Sustained biochemical and virological response of different HCV genotypes to Interferon-alpha plus ribavirin combination therapy. Pharmacologyonline. 2010;2:161–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalantari H, Kazemi F, Minakari M. Efficacy of triple therapy with interferon alpha-2b, ribavirin and amantadine in the treatment of naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Res Med Sci. 2007;12:178–85. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khalid SR, Khan AA, Alam A, Lak NH, Butt AK, Shafqat F, et al. Interferon-ribavirin treatment in chronic hepatitis C – the less talked about aspects. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan AA, Sarwar S. Response to combination therapy in hepatitis virus C genotype 2 and 3. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:473–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khokhar N. Effectiveness of 48 weeks interferon alfa-2b in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment of chronic hepatitis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2002;14:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muhammad N, Jan MA, Rahman N. Outcome of combined interferon-ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:651–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrenkiene V, Gudinaviciene I, Jonaitis L, Kupcinskas L. Interferon alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: assessment of virological, biochemical and histological treatment response. Medicina (Kaunas) 2004;40:538–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pramoolsinsap C, Poovorawan Y, Sura T, Theamboonlers A, Busagorn N, Kurathong S. Hepatitis G infection and therapeutic response to interferon in HCV-related chronic liver disease. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:480–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qureshi S, Batool U, Iqbal M, Qureshi O, Kaleem R, Aziz H, et al. Response rates to standard interferon treatment in HCV genotype 3a. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:10–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarwar S, Butt AK, Khan AA, Alam A, Ahmad I, Dilshad A. Serum alanine aminotransferase level and response to interferon-ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:460–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarwar STS. Treatment failure in chronic hepatitis C: predictors other than viral kinetics. Rawal Med J. 2010;35:217–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiavon LL, Narciso-Schiavon JL, Carvalho-Filho RJ, Sampaio JP, El Batah PN, Silva GA, et al. Evidence of a significant role for fast-mediated apoptosis in HCV clearance during pegylated interferon plus ribavirin combination therapy. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:291–8. doi: 10.3851/IMP1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaker OG, Eskander EF, Yahya SM, Mohamed MS, Abd-Rabou AA. Genetic variation in BCL-2 and response to interferon in hepatitis C virus type 4 patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:593–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen C, Hu T, Shen L, Gao L, Xie W, Zhang J. Mutations in ISDR of NS5A gene influence interferon efficacy in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sixtos-Alonso MS, Sanchez-Munoz F, Sanchez-Avila JF, Martinez RA, Dominguez Lopez A, Vargas Vorackova F, et al. IFN-stimulated gene expression is a useful potential molecular marker of response to antiviral treatment with Peg-IFNalpha 2b and ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Arch Med Res. 2011;42:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Awasthi G. Chronic hepatitis C — treatment results in northern India. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:172–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stefano JT, Correa-Giannella ML, Ribeiro CM, Alves VA, Massarollo PC, Machado MC, et al. Increased hepatic expression of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3821–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i24.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suresh RL, Kananathan R, Merican I. Chronic hepatitis C — a study of 105 cases between 1990-2000. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56:243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szanto P, Grigorescu M, Dumitru I, Serban A. Steatosis in hepatitis C virus infection. Response to anti-viral therapy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuberi BF, Zuberi FF, Memon SA, Qureshi MH, Ali SZ, Afsar S. Sustained virological response based on rapid virological response in genotype-3 chronic hepatitis C treated with standard interferon in the Pakistani population. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2218–21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carneiro MV, Souza FF, Teixeira AC, Figueiredo JF, Villanova MG, Secaf M, et al. The H63D genetic variant of the HFE gene is independently associated with the virological response to interferon and ribavirin therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1204–10. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833bec1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barone AA, Tosta RA, Tengan FM, Marins JH, Cavalheiro Nde P, Cardi BA. Are anti-interferon antibodies the cause of failure in chronic HCV hepatitis treatment? Braz J Infect Dis. 2004;8:10–7. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702004000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carneiro VL, Lemaire DC, Bendicho MT, Souza SL, Cavalcante LN, Angelo AL, et al. Natural killer cell receptor and HLA-C gene polymorphisms among patients with hepatitis C: a comparison between sustained virological responders and non-responders. Liver Int. 2010;30:567–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar D, Malik A, Asim M, Chakravarti A, Das RH, Kar P. Response of combination therapy on viral load and disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1107–13. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vigani AG, Macedo de Oliveira A, Tozzo R, Pavan MH, Goncales ES, Fais V, et al. The association of cryoglobulinaemia with sustained virological response in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e91–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Villela-Nogueira CA, Perez RM, de Segadas Soares JA, Coelho HS. Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) as an independent predictive factor of sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C treated with interferon-alpha and ribavirin. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:728–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000174025.19214.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parise ER, de Oliveira AC, Conceicao RD, Amaral AC, Leite K. Response to treatment with interferon-alpha and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotypes 2 and 3 depends on the degree of hepatic fibrosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:78–81. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702006000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheinquer N, Cheinquer H, Wolff FH, Coelho-Borges S. Effect of sustained virologic response on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV cirrhosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14:457–61. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702010000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gupta R, Ramakrishna CH, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Banerjee R, Reddy DN. Efficacy of low dose peginterferon alpha-2b with ribavirin on chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5554–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liao XW, Ling Y, Li XH, Han Y, Zhang SY, Gu LL, et al. Association of genetic variation in IL28B with hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance in the Chinese Han population. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:141–7. doi: 10.3851/IMP1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Araújo ES, Dahari H, Neumann AU, de Paula Cavalheiro N, Melo CE, de Melo ES, et al. Very early prediction of response to HCV treatment with PEG-IFN-alfa-2a and ribavirin in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aziz H, Gil ML, Waheed Y, Adeeb U, Raza A, Bilal I, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors for peg interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin treatment on HCV infected patients in Pakistan. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:640–5. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Butt AS, Mumtaz K, Aqeel I, Shah HA, Hamid S, Jafri W. Sustained virological response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin in patients with genotype 3 HCV cirrhosis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30:207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Almeida PR, de Mattos AA, Amaral KM, Feltrin AA, Zamin P, Tovo CV, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C with peginterferon and ribavirin in a public health program. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:223–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Esmat G, Fattah SA. Evaluation of a novel pegylated interferon alpha-2a (Reiferon Retard®) in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C - genotype 4. Digest Liver Dis Suppl. 2009;;3:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gonçales FL, Jr, Vigani A, Goncales N, Barone AA, Araujo E, Focaccia R, et al. Weight-based combination therapy with peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin for naive, relapser and non-responder patients with chronic hepatitis C. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:311–6. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702006000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Males S, Gad RR, Esmat G, Abobakr H, Anwar M, Rekacewicz C, et al. Serum alpha-foetoprotein level predicts treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:797–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Narciso-Schiavon JL, Freire FC, Suarez MM, Ferrari MV, Scanhola GQ, de Lucca Schiavon L, et al. Antinuclear antibody positivity in patients with chronic hepatitis C: clinically relevant or an epiphenomenon? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:440–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283089392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Narciso-Schiavon JL, de Lucca Schiavon L, Carvalho-Filho RJ, Sampaio JP, Batah PN, Barbosa DV, et al. Gender influence on treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:217–23. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parise ER, de Oliveira AC, Ferraz ML, Pereira AB, Leite KR. Cryoglobulinemia in chronic hepatitis C: clinical aspects and response to treatment with interferon alpha and ribavirin. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49:67–72. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652007000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pereira PS, Silva IS, Uehara SN, Emori CT, Lanzoni VP, Silva AE, et al. Chronic hepatitis C: hepatic iron content does not correlate with response to antiviral therapy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:331–6. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ray G, Pal S, Nayyar I, Dey S. Efficacy and tolerability of pegylated interferon alpha 2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C — a report from eastern India. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rossignol JF, Elfert A, Keeffe EB. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C using a 4-week lead-in with nitazoxanide before peginterferon plus nitazoxanide. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:504–9. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181bf9b15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silva GF, Polonio RJ, Pardini MI, Corvino SM, Henriques RM, Peres MN, et al. Using pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin to treat chronic hepatitis patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1: are nonresponders and relapsers different populations? Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:554–60. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Bansal M. Pegylated interferon alfa 2b and oral ribavirin in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:283–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Taha AA, El-Ray A, El-Ghannam M, Mounir B. Efficacy and safety of a novel pegylated interferon alpha-2a in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:597–602. doi: 10.1155/2010/717845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tohra SK, Taneja S, Ghosh S, Sharma BK, Duseja A, Dhiman RK, et al. Prediction of sustained virological response to combination therapy with pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin in patients with genotype 3 chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2449–55. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1770-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lerias de Almeida PR, Alves de Mattos A, Valle Tovo C. Sustained virological response according to the type of early virological response in HCV and HCV/HIV. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:150–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khattab M, Eslam M, Sharwae MA, Shatat M, Ali A, Hamdy L. Insulin resistance predicts rapid virologic response to peginterferon/ribavirin combination therapy in hepatitis C genotype 4 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1970–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.El Makhzangy H, Esmat G, Said M, Elraziky M, Shouman S, Refai R, et al. Response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1576–83. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bader el-Din NG, Abd el-Meguid M, Tabll AA, Anany MA, Esmat G, Zayed N, et al. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits response of chronic hepatitis-C-virus-infected patients to interferon-based therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shaker O, Ahmed A, Doss W, Abdel-Hamid M. MxA expression as marker for assessing the therapeutic response in HCV genotype 4 Egyptian patients. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:794–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Belhadj N, Houissa F, Elloumi H, Ouakaa A, Gargouri D, Romani M, et al. Virological response of Tunisians patients treated by peginterferon plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C: a preliminary study. Tunis Med. 2008;86:341–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chuang JY, Yang SS, Lu YT, Hsieh YY, Chen CY, Chang SC, et al. IL-10 promoter gene polymorphisms and sustained response to combination therapy in Taiwanese chronic hepatitis C patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gao DY, Zhang XX, Hou G, Jin GD, Deng Q, Kong XF, et al. Assessment of specific antibodies to F protein in serum samples from Chinese hepatitis C patients treated with interferon plus ribavirin. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3746–51. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00612-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gheorghe L, Grigorescu M, Iacob S, Damian D, Gheorghe C, Iacob R, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of pegylated Interferon alpha-2a and ribavirin combination therapy in Romanian patients with chronic hepatitis C: from clinical trials to clinical practice. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gheorghe L, Iacob S, Grigorescu M, Sporea I, Sirli R, Damian D, et al. High sustained virological response rate to combination therapy in genotype 1 patients with histologically mild hepatitis C. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gheorghe L, Iacob S, Sporea I, Grigorescu M, Sirli R, Damian D, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and predictive factors for early and sustained virologic response in patients treated with weight-based dosing regimen of PegIFN alpha-2b ribavirin in real-life healthcare setting. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:23–9. doi: 10.1007/s11749-007-0047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ibrahim M, Gomaa W, Ibrahim Y, El Hadad H, Shatat M, Aleem AA, et al. Nitric oxide levels and sustained virological response to pegylated-interferon alpha2a plus ribavirin in chronic HCV genotype 4 hepatitis: a prospective study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jabbari H, Bayatian A, Sharifi AH, Zaer-Rezaee H, Fakharzadeh E, Asadi R, et al. Safety and efficacy of locally manufactured pegylated interferon in hepatitis C patients. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13:306–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kumthip K, Pantip C, Chusri P, Thongsawat S, O'Brien A, Nelson KE, et al. Correlation between mutations in the core and NS5A genes of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1a, 1b, 3a, 3b, 6f and the response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Laufer N, Bolcic F, Rolon MJ, Martinez A, Reynoso R, Perez H, et al. HCV RNA decline in the first 24 h exhibits high negative predictive value of sustained virologic response in HIV/HCV genotype 1 co-infected patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin. Antiviral Res. 2011;90:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Njouom R, Sartre MT, Timba I, Nerrienet E, Tchendjou P, Pasquier C, et al. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alpha-2a/ribavirin in treatment-naive Cameroonian patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2008;80:2079–85. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ridruejo E, Adrover R, Cocozzella D, Fernandez N, Reggiardo MV. Efficacy, tolerability and safety in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C with combination of peg-interferon - ribavirin in daily practice. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Seow EL, Robert Ding PH. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b (peg-intron) plus ribavirin (rebetol) in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a local experience. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60:637–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sombie RBA, Somda S, Sangare L, Lompo O, Kabore Z, Tieno H, et al. Chronic hepatitis C: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment in Yalgado-Ouedraogo teaching hospital in Ouagadougou. J Afr Hepato Gastroenterol. 2011;5:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sporea I, Sirli R, Curescu M, Gheorghe L, Popescu A, Bota S, et al. Outcome of antiviral treatment in patients with chronic genotype 1 HCV hepatitis: a retrospective study in 507 patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Su WP,, Peng CY, Lai HC, Liao KF, Huang WH, Chuang PH, et al. Persistent transaminase elevations in chronic hepatitis C patients with virological response during peginterferon and ribavirin therapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yu JW, Sun LJ, Zhao YH, Kang P, Gao J, Li SC. Analysis of the efficacy of treatment with peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin in patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2009;29:1485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yu JW, Wang GQ, Sun LJ, Li XG, Li SC. Predictive value of rapid virological response and early virological response on sustained virological response in HCV patients treated with pegylated interferon alpha-2a and ribavirin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:832–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhou YQ, Wang XH, Hong GH, Zhu Y, Zhang XQ, Hu YJ, et al. Twenty-four weeks of pegylated interferon plus ribavirin effectively treat patients with HCV genotype 6a. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.de Segadas-Soares JA, Villela-Nogueira CA, Perez RM, Nabuco LC, Brandao-Mello CE, Coelho HS. Is the rapid virologic response a positive predictive factor of sustained virologic response in all pretreatment status genotype 1 hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon-alpha2b and ribavirin? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:362–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181775e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jovanović M, Jovanović B, Potic M, Konstantinović L, Vrbic M, Radovanovic-Dinic B, et al. Characteristics of chronic hepatitis C among intravenous drug users: a comparative analysis. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10:153–7. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2010.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Awad T, Thorlund K, Hauser G, Stimac D, Mabrouk M, Gluud C. Peginterferon alpha-2a is associated with higher sustained virological response than peginterferon alfa-2b in chronic hepatitis C: systematic review of randomized trials. Hepatology. 2010;51:1176–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.23504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Swan T. The hepatitis C treatment pipeline report New York: Treatment Action Group; 2011. Available from: http://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/uploadedFiles/About/Publications/TAG_Publications/2011/HCV%20pipeline%202011%20final.pdfhttp://[accessed 12 January 2012].

- 118.Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shah NS, Andrews JR, Friedland GH, Moll AP, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:153–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S. A new standard of care for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:257–64. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Opar A. Excitement grows for potential revolution in hepatitis C virus treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:501–3. doi: 10.1038/nrd3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]