Abstract

Little is known about the early mechanisms mediating left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis (HH). However, the increased oxidative stress related to iron overload may be involved in this process, and strain rate (SR), a sensitive echocardiography derived measure of diastolic function, may detect such changes. Thus, we evaluated the relationship between left ventricular diastolic function measured with tissue Doppler SR and oxidative stress in asymptomatic HH subjects and control normal subjects. Ninety-four consecutive visits of 43 HH subjects, age 30 to 74 (50 ± 10, mean ± SD) and 37 consecutive visits of 21 normal volunteers age 30 to 63 (48 ± 8) were evaluated over a three-year period. SR was obtained from the basal septum in apical 4 chamber views. All patients had confirmed C282Y homozygosity, a documented history iron overload and were New York Heart Association functional class I. Normal volunteers lacked HFE gene mutations causing HH. In the HH subjects, the SR demonstrated moderate, but significant correlations with biomarkers of oxidative stress; however, no correlations were noted in normal subjects. The biomarkers of iron overload per se did not show significant correlations with the SR. Although our study was limited by the relatively small subject number, these results suggest that a possible role of oxidative stress to affect LV diastolic function in asymptomatic HH subjects and SR imaging may be a sensitive measure to detect that effect.

Keywords: hereditary hemochromatosis, left ventricular diastolic function, oxidativestress, strain rate, iron overload, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Recently, we reported1 that augmented atrial function was present in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis, (HH) and we speculated that this finding may be due to a compensatory response to early alteration of left ventricular (LV) diastolic function in this group. In that report, the peak early filling strain rate of the basal septum of the left ventricle, which is known to be a very sensitive index of cardiac function in various cardiac pathologic states,2–6 tended to be decreased when compared with normal volunteers, although these changes were not statistically significant.1 This observation indicates that alteration of LV diastolic function may occur subclinically in HH during the asymptomatic phase of the disease. Furthermore, we found that oxidative stress levels were persistently elevated in this population regardless of their treatment status.7 Elevated oxidative stress has been shown to alter cardiac function in experimental settings.8–12 Based on these considerations, we hypothesize that increased oxidative stress related to iron overload affects LV diastolic function in asymptomatic HH subjects. Thus, we conducted this study to assess correlations between tissue Doppler measured SR from the basal septum, a sensitive measure of LV diastolic function, and biomarkers of oxidative stress.

METHODS

Subjects and study design

We studied data obtained from a series of outpatient visits between September 2003 and August 2006 of HH subjects and age and gender matched healthy controls who participated in a NHLBI-approved protocol, number 03-H-0282, previously described.1,13 Ninety-four consecutive visits of 43 HH subjects, age 30 to 74 (50 ± 10, mean ± SD) with 13 females (30%) and 37 consecutive visits of 21 normal volunteers age 30 to 63 (48 ± 8) 7 females (33%) were evaluated over this period. All subjects provided written informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under a protocol consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.14 Eligibility criteria for study participation among HH subjects were detailed previously,1,13 and included: 1) age 21 years or older, 2) NYHA functional class I, 3) genetic study showing homozygosity for the C282Y HFE gene, 4) transferrin saturation > 60% or a serum ferritin > 400 μg/L at the time of original diagnosis, and 5) absence of significant liver disease or arthritis due to HH. Eligibility criteria for normal volunteer subjects included: 1) age 21 years or older, 2) NYHA functional class I, 3) genetic studies showing absence of C282Y or H63D HFE mutations, 4) normal transferrin saturation and serum ferritin. Subjects were recruited with the assistance of the NIH Clinical Center Patient Recruitment and Public Liaison Office and via direct mailings of study information to physicians as previously reported.1,13

Echocardiographic measurements

All subjects underwent transthoracic resting echocardiography with tissue Doppler strain rate (SR) measurements and assessment of biomarkers of oxidative stress and iron overload at each visit. SR imaging of both systolic and diastolic phases were obtained using multifrequency transducers with center frequencies of 2.5 or 3.5 MHz (Vivid 7, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) as we previously described.1,15

Biomarkers of oxidative stress

Erythrocyte glutathione levels, erythrocyte superoxide dismutase levels, and plasma lipid peroxidation levels, which were assessed as the sum of malondedialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2(E)-nonenal, were measured as biomarkers of oxidative stress as we previously reported.7 Serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin saturation were measured as markers of iron overload.

Statistical analysis

Pearson linear correlation analysis was used to assess whether there was an association between biomarkers of SR and biomarkers of oxidative stress, or iron overload. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

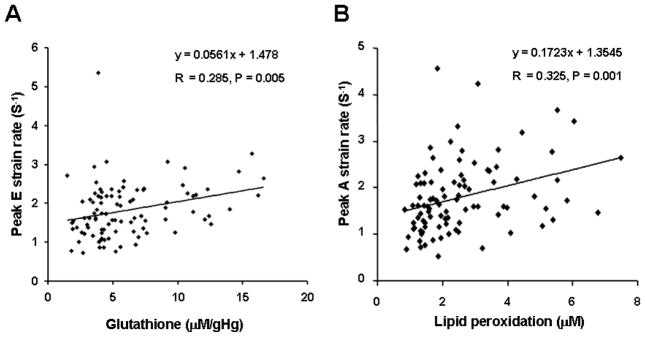

Demographic characteristics of the study group have been published previously.1,13 In this study group, only one subject demonstrated borderline decreased LV ejection fraction (50%) at one visit. The other subjects showed normal LV ejection fraction ≥55% measured with the modified biplane Simpson method throughout the visits. All subjects were confirmed to have normal contractile reserve without evidence of myocardial ischemia in stress exercise echocardiography as previously reported.13 In HH subjects, SR measurements significantly correlated with the biomarkers of oxidative stress (Table 1), but not with iron overload (Table 2). Among the analyses performed, peak diastolic early filling SR positively correlated with erythrocyte glutathione levels (r=0.285, P=0.005, peak diastolic early filling SR = 0.056 × glutathione + 1.478. Figure 1A), and peak diastolic atrial contraction SR positively correlated with plasma malonedialdehyde levels (r=0.325, P=0.001, peak diastolic atrial contraction SR = 0.172 × malondealdehyde + 1.354, Figure 1B). Elevated oxidative stress has reported to decrease erythrocyte glutathione levels 16–18 and elevate plasma malondialdehyde levels in humans;16–18 therefore, our results suggest that elevated oxidative stress may decrease diastolic early filling SR and increase diastolic atrial contraction SR (Figure 1). When the visits of the HH subjects were classified into those with newly diagnosed HH subjects (N=22) and chronically phlebotomized HH subjects (N=72) based on our criteria published,1,13 i.e., more than 6 months of therapeutic phlebotomy with stable body iron levels, similar relations between erythrocyte glutathione levels and peak diastolic early filling SR and between peak diastolic atrial contraction SR and plasma malondialdehyde levels were observed. The correlations appeared to be more pronounced in newly diagnosed HH subjects (table 3). The correlation between peak early diastolic filling SR and plasma malondialdehyde became significant in only newly diagnosed HH subjects.

Table 1.

Correlations between Strain Rate Measurements with Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Subjects with Hereditary Hemochromatosis and Normal Volunteers.

| Variables | Glutathione | Superoxide Dismutase | Malondialdehyde | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis | N=94 | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | 0.285 | 0.005* | 0.104 | 0.321 | 0.079 | 0.449 |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | 0.022 | 0.832 | −0.073 | 0.483 | 0.325 | 0.001* |

| Normal Volunteers | N=37 | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | −0.058 | 0.731 | 0.037 | 0.828 | −0.183 | 0.279 |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | −0.101 | 0.550 | 0.065 | 0.704 | −0.122 | 0.470 |

SR= Doppler measured strain rate. Glutathione and superoxide dismutase levels were measured in erythrocytes. Malondialdehyde was measured in plasma. P indicates probability and R indicates correlation coefficient.

P<0.05.

Table 2.

Correlations between Strain Rate Measurements with Biomarkers of Iron Overload in Subjects with Hereditary Hemochromatosis and Normal Volunteers.

| Variables | Ferritin | Serum iron | Transferrin saturation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis | N=94 | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | −0.102 | 0.314 | 0.008 | 0.941 | 0.065 | 0.523 |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | −0.027 | 0.787 | 0.099 | 0.328 | 0.127 | 0.212 |

| Normal Volunteers | N=37 | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | −0.132 | 0.436 | −0.197 | 0.242 | −0.166 | 0.325 |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | 0.070 | 0.682 | −0.131 | 0.439 | −0.080 | 0.637 |

SR= Doppler measured strain rate. P indicates probability and R indicates correlation coefficient.

P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Significant Correlation Between Echocardiographic Strain Rate Measurements and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Glutathione was measured from erythrocytes and lipid peroxidation was measured from plasma. E = early diastolic filling, A = atrial contraction, gHg; gram hemoglobin.

Table 3.

Correlations between Strain Rate Measurements with Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Subsets of Subjects with Hereditary Hemochromatosis.

| Variables | Glutathione | Superoxide Dismutase | Malondealdehyde | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis | Newly diagnosed (N=22) | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | 0.440 | 0.041* | 0.247 | 0.267 | 0.485 | 0.022* |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | 0.104 | 0.644 | 0.215 | 0.338 | 0.541 | 0.009* |

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis | Chronically phlebotomized (N=72) | |||||

| Peak early filling SR | 0.234 | 0.048* | 0.075 | 0.531 | −0.031 | 0.798 |

| Peak atrial contraction SR | −0.021 | 0.862 | −0.152 | 0.201 | 0.251 | 0.034* |

SR= Doppler measured strain rate. Glutathione and superoxide dismutase levels were measured in erythrocytes. Malondialdehyde was measured in plasma. P indicates probability and R indicates correlation coefficient.

P<0.05.

In normal volunteers, SR measurements correlated with neither biomarkers of oxidative stress nor iron overload (Table 1 & 2). Although the data are not shown, the other echocardiographic measures of LV diastolic function including peak diastolic early filling tissue mitral annulus pulsed wave Doppler tissue velocities, peak diastolic atrial contraction mitral annulus pulsed wave tissue velocities, mitral valve inflow peak early filling and atrial contraction velocities, mitral inflow deceleration time, isovolumic relaxation time failed to show a significant correlation with biomarkers of oxidative stress. In addition, none of the standard mathematical transformations on measures of cardiac function or oxidative stress improved the linear fit (correlation) between the variables.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that LV diastolic function, measured with SR, correlated with oxidative stress in symptomatic HH subjects, but not in normal volunteers. Despite the description of significant cardiac disease in advanced HH19,20 and the relatively high frequency of HFE gene mutations in the population,16 our previous publications1,13 appear to be the only studies which examine cardiac function in a group of asymptomatic HH individuals. There are no other studies that have evaluated the natural history of cardiac disease in this group in order to identify early cardiac functional abnormalities and the mechanisms producing these abnormalities. Our study suggests that oxidative stress may affect LV diastolic function during the asymptomatic phase in HH subjects.

The direct association between iron overload and cardiac dysfunction has been reported in both clinical and experimental studies. Although oxidative stress appears to affect LV diastolic function as described in experimental settings such as hypertension,8 diabetes,9 doxorubicin cardiomyopathy,10 and heart failure,11,12 its affect has not been tested in HH subjects. Our results suggest that oxidative stress may modulate LV diastolic function with normal LV systolic function before the effect of iron overload becomes detectable in the asymptomatic stage of this condition.

Inability of the other echocardiographic measures of LV diastolic function in our study further supports that SR derived from tissue Doppler echocardiography is a sensitive marker of LV diastolic function as previously reported.2–4 Our observations suggest that evaluating and monitoring SR in individuals with evidence of iron overload may be a sensitive test to identify subsets of patients with increased oxidative stress, such as patients with HH. Further investigation of the use of SR to detect subclinical LV diastolic function in various cardiac conditions is warranted.

We have previously described that aggressive iron removal therapy does not have a significant effect on cardiac function in this population.13 It is noteworthy, therefore, that oxidative stress levels remain persistently elevated during the maintenance phase of treatment despite aggressive iron removal.7 The association between LV diastolic function and elevated oxidative stress found in this study suggest that it may be helpful to monitor oxidative stress in HH subjects as a marker of the cardiac manifestation of HH.

Although iron overload has been shown to adversely affect LV diastolic function in other patient groups,21,22 we could not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between SR and iron overload during the asymptomatic phase of HH. It is still possible that this may be due to the relatively small sample size or lack of sufficient sensitivity of the measurements performed. On the other hand, some statistically significant results in the HH subjects may be chance findings, due to the multiple comparisons tested.

In addition, the relatively low correlation coefficients (albeit statistically significant) between cardiac function and biomarkers of oxidative stress in our study suggest that there may be additional unidentified causal factors that modulate cardiac function or that the biomarkers we used have limited sensitivity.

Our study’s limitations include the following: we used SR measurements to assess LV diastolic function; however, other forms of cardiac imaging might be more sensitive in detecting closer associations. We did not measure SR at other than basal septum of the left ventricle in this study due to our technical limitations. Other locations of the left ventricle may be more susceptible to the changes related to HH. We studied only HH subjects who had homozygous C282Y HFE mutations, and did not include subjects with the compound heterozygote genotype (C282Y/H63D). Although more than 80% of iron overload cases resulting from HFE polymorphisms are associated with homozygosity for the C282Y HFE mutation,23 it is possible that the effect of iron overload in other HFE genotypes may be different.

In summary, our study suggests a possible role of oxidative stress in the modulation of LV diastolic function measured with tissue Doppler echocardiography derived SR in asymptomatic subjects with HH. A larger scale study is needed to verify our observations and future research into whether SR imaging can be used to determine prognosis and outcome of HH subjects should provide clinically valuable information.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the intramural research program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

The correspondence author is a special volunteer investigator of the Cardiovascular Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

References

- 1.Shizukuda Y, Bolan CD, Tripodi DJ, et al. Significance of left atrial contractile function in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:954–959. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidemann F, Breunig F, Beer M, et al. Improvement of cardiac function during enzyme replacement therapy in patients with Fabry disease: a prospective strain rate imaging study. Circulation. 2003;108:1299–12301. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091253.71282.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato TS, Noda A, Izawa H, et al. Discrimination of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy on the basis of strain rate imaging by tissue Doppler ultrasonography. Circulation. 2004;110:3808–3814. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150334.69355.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niedeggen A, Breithardt OA, Franke A. Detection of early systolic dysfunction with strain rate imaging in a patient with light chain cardiomyopathy. Z Kardiol. 2005;94:133–136. doi: 10.1007/s00392-005-0175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulel O, Soylu K, Yazici M, et al. Longitudinal diastolic myocardial functions are affected by chronic smoking in young healthy people: a study of color tissue Doppler imaging. Echocardiography. 2007;24:494–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulel O, Soylu K, Yuksel S, et al. Evidence of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction by color tissue Doppler imaging despite normal ejection fraction in patients on chronic hemodialysis program. Echocardiography. 2008;25:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shizukuda Y, Bolan CD, Nguyen TT, et al. Oxidative stress in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:249–450. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo P, Nishiyama A, Rahman M, et al. Contribution of reactive oxygen species to the pathogenesis of left ventricular failure in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats: effects of angiotensin II blockade. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226200.73065.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye G, Metreveli NS, Ren J, et al. Metallothionein prevents diabetes-induced deficits in cardiomyocytes by inhibiting reactive oxygen species production. Diabetes. 2003;52:777–783. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shizukuda Y, Matoba S, Mian OY, et al. Targeted disruption of p53 attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;273:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-5905-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, et al. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals originating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 2000;86:152–157. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shizukuda Y, Buttrick PM. Oxygen free radicals and heart failure: new insight into an old question. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L237–L238. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00111.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shizukuda Y, Bolan CD, Tripodi DJ, et al. Left ventricular systolic function during stress echocardiography exercise in subjects with asymptomatic hereditary hemochromatosis. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:694–698. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 1997;277:925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachdev V, Aletras AH, Padmanabhan S, et al. Myocardial strain decreases with increasing transmurality of infarction: a Doppler echocardiographic and magnetic resonance correlation study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwose EU, Jelinek HF, Richards RS, et al. Erythrocyte oxidative stress in clinical management of diabetes and its cardiovascular complications. Br J Biomed Sci. 2007;64:35–43. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2007.11732754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozdemir G, Ozden M, Maral H, et al. Malondialdehyde, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase and homocysteine levels in type 2 diabetic patients with and without microalbuminuria. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42:99–104. doi: 10.1258/0004563053492838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donmez G, Derici U, Erbas D, et al. The effects of losartan and enalapril therapies on the levels of nitric oxide, malondialdehyde, and glutathione in patients with essential hypertension. Jpn J Physiol. 2002;52:435–440. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.52.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finch SC, Finch CA. Idiopathic hemochromatosis, an iron storage disease. A. Iron metabolism in hemochromatosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1955;34:381–430. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabestani A, Child JS, Perloff JK, et al. Cardiac abnormalities in primary hemochromatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;526:234–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb55509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schafer AI, Cheron RG, Dluhy R, et al. Clinical consequences of acquired transfusional iron overload in adults. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:319–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102053040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson LJ, Baldus WP, Tajik AJ. Echocardiographic features of idiopathic hemochromatosis. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:885–889. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beutler E, Felitti V, Gelbart T, et al. The effect of HFE genotypes on measurements of iron overload in patients attending a health appraisal clinic. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:329–337. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]