Background: Although Tic22 is involved in protein import into chloroplasts, the function in cyanobacteria is unknown.

Results: Cyanobacterial Tic22 is required for OM biogenesis, shares structural features with chaperones, and can be substituted by plant Tic22.

Conclusion: Tic22, involved in outer membrane biogenesis, is functionally conserved in cyanobacteria and plants.

Significance: The findings are important for the understanding of periplasmic protein transport.

Keywords: Cell Wall, Chaperone Chaperonin, Crystal Structure, Cyanobacteria, Protein Translocation

Abstract

Mitochondria and chloroplasts are of endosymbiotic origin. Their integration into cells entailed the development of protein translocons, partially by recycling bacterial proteins. We demonstrate the evolutionary conservation of the translocon component Tic22 between cyanobacteria and chloroplasts. Tic22 in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 is essential. The protein is localized in the thylakoids and in the periplasm and can be functionally replaced by a plant orthologue. Tic22 physically interacts with the outer envelope biogenesis factor Omp85 in vitro and in vivo, the latter exemplified by immunoprecipitation after chemical cross-linking. The physical interaction together with the phenotype of a tic22 mutant comparable with the one of the omp85 mutant indicates a concerted function of both proteins. The three-dimensional structure allows the definition of conserved hydrophobic pockets comparable with those of ClpS or BamB. The results presented suggest a function of Tic22 in outer membrane biogenesis.

Introduction

Mitochondria and chloroplasts originated from bacteria by evolutionary adaptation after inheritance by the host cell (1, 2), with the latter enforcing the development of machines for translocation of cytosolically synthesized proteins into these organelles. These machines originated in parts from bacterial proteins forming a minimal system of only few components, whereas additional factors were added in the course of evolution to enhance specificity and/or kinetics of translocation (3, 4). Distinct membrane-localized complexes are responsible for sorting of proteins into the different compartments of the organelles (5–7). The translocons on the outer or inner chloroplast envelope (TOC/TIC) are required for the transfer of preproteins into the stroma (6, 7), and transfer of preproteins across the intermembrane space is assisted by Tic22 (8–10).

Albeit bacterial homologues to several mitochondrial and chloroplast translocon components were identified (3, 4, 11), a functional relationship is only established for Toc75-III, Sam50, and the bacterial Omp85 (3, 4, 11, 12). The bacterial Omp85 is involved in membrane insertion of bacterial OMPs (13), which is conserved for Sam50 and most likely for Toc75-V/Oep80, whereas Toc75-III is involved in the translocation of proteins across the membrane (14). By this, the central component of the eukaryotic translocation machines appears to be inherited from bacteria.

Omp85 proteins N-terminally contain a repeat of polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) segments, which is called a POTRA domain, and C-terminally contain a membrane-embedded β-barrel (14 and 15 and references therein). The N-terminal POTRA7 domain of the protein from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (Anabaena sp. hereafter) encoded by alr2269 is composed of three POTRA elements (e.g. 16 and 17) and is discussed to represent some kind of a receptor domain. The precise function of the POTRA domain, however, is not yet fully explored and might differ for the Omp85 proteins from different bacteria (14, 15).

Remarkably, the periplasmic Tic22 also is found in both cyanobacteria and plastids (see Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1) (9, 18, 19). In plastids, it is the only known soluble intermembrane space component interacting with the translocation complexes in both enve lopes (8–10). The molecular function of cyanobacterial Tic22 is presently unclear. In Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Tic22 (Slr0924) was identified in the periplasmic proteome (19), whereas a thylakoid localization was suggested by immunoelectron microscopy (18).

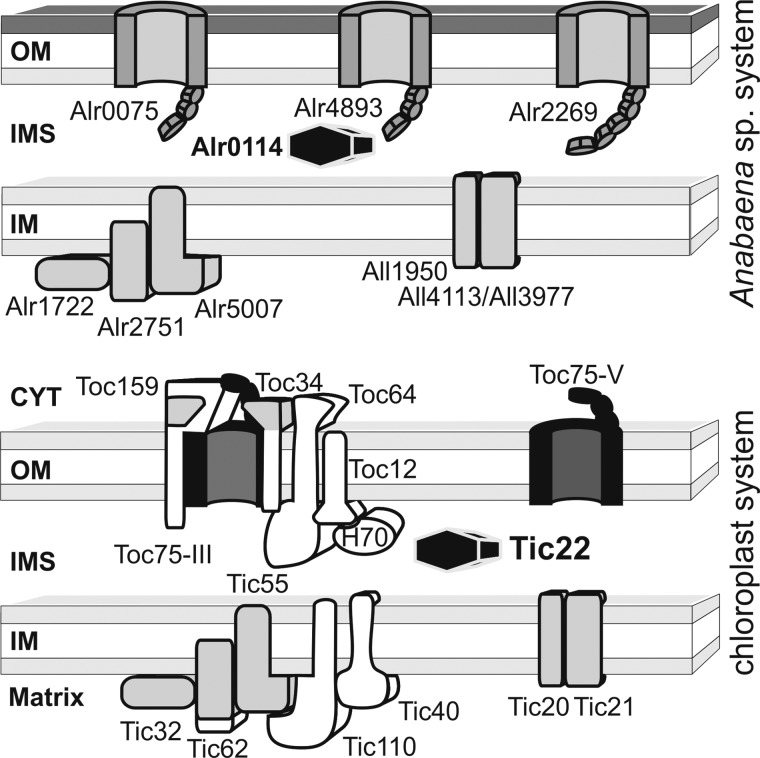

FIGURE 1.

Evolutionary conservation of the chloroplast protein translocation system. Analysis of TOC or TIC components shows that most of the identified components have homologues in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (protein name is chosen according to the gene name). Exceptions for which a homologue is not identified are shown in white. The functional relation between Toc75 (black) and the cyanobacterial Omp85 (encoded by alr0075, alr4893, alr2269) was demonstrated previously (4). Chloroplast proteins marked in gray showcases where proteins (e.g. Tic20, Tic21, etc.) or protein domains (Toc159; Toc34, Tic62) have possibly been recycled to a new function. The investigated Tic22 is highlighted (Alr0114; anaTic22). OM, outer membrane; IMS, inner membrane space; IM, inner membrane; CYT, cytosol.

Here, we show that anaTic22 (Alr0114) from Anabaena sp. is soluble and localized in both the thylakoids and periplasm. tic22 mutants show a similar phenotype as omp85 mutants and a physical interaction between anaTic22 and anaOmp85 was observed. The crystallographic three-dimensional structure of anaTic22 revealed a novel fold with hydrophobic surface pockets. Similar pockets binding to aromatic amino acids were observed for ClpS (20) and BamB (21), suggesting that Tic22 recognizes the C-terminal OMP signal containing an aromatic amino acid (13). On the one hand, this provides insights into the periplasmic protein transport system in cyanobacteria; on the other hand, Tic22 provides a second example for functional conservation between bacterial and chloroplast proteins in protein translocation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation, Growth, and handling of Anabaena Strains

Plasmids (Table 1) or Anabaena strains (Table 2) were described or generated as established (22–24). For cloning of alr0114 (anatic22), PCR was performed on genomic DNA of Anabaena sp. (supplemental Table S1) (23). For complementation, the ORF of anatic22 was fused to the copper-regulated promoter petJ and cloned into pALH1, a derivate of pRL271 where CmR/EmR and the SacB gene were replaced by the neomycin resistance cassette C.K1. Mutants of anatic22 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. The construct of atTic22-IV was produced by RT-PCR, and the ORF was fused to the promoter of petJ and the coding sequence for Alr0114 signal peptide determined by SignalP (25). Cultures of Anabaena were grown in BG11 (26) supplemented as described (23, 24). The analysis of GFP fluorescence and Anabaena sp. fractionation was performed as described (16, 27).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids generated in this study

| Plasmid | Resistancea | Source plasmid | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| panaTic22 | AmpR | pET21bb | |

| panaOMP85-POTRAc | AmpR | Topo-TrcHis2d | |

| pJT13 | SpR/SmR | pCSEL24e | pCSEL24 (Palr0114/GFP) |

| pJT14 | SpR/SmR | pRL271f | pRL271 (orfalr0114 bp 1–404/SpR/SmR/423–825) |

| pALH1 | NmR | pRL271 | pRL271 sacB::NmR |

| pALH2 | NmR | pALH1 | pALH1 (PpetJ/alr0114) |

| pALH3 | NmR | pALH1 | pALH1 (PpetJ/alr0114 D213R) |

| pALH4 | NmR | pALH1 | pALH1 (PpetJ/alr0114 I219R) |

| pALH5 | NmR | pALH1 | pALH1 (PpetJ/alr0114 F136G) |

| pALH6 | NmR | pALH1 | pALH1 (PpetJ/ssalr0114-atTic22) |

TABLE 2.

Used and generated strains

Sp (spectinomycin), Sm (streptomycin), Nm (neomycin) AFS (Anabaena sp., mutant created in Frankfurt by a member of the Schleiff group), AFS-I (AFS with an insertion in the gene specified), and AFS-PDGF (promoter downstream GFP fusion).

| Strain | Resistance | Genotype | Relevant properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFS-I-tic22 | SpR/SmR | alr0114::pJT14 | Gene interruption | This study |

| AFS-Ι-alr0075 | SpR/SmR | alr0075::SpR/SmR | Gene interruption | Ref. 23 |

| AFS-Ι-alr2269 | SpR/SmR | alr2269::SpR/SmR | Gene interruption | Ref. 23 |

| AFS-Ι-alr2270 | SpR/SmR | alr2270::SpR/SmR | Gene interruption | Ref. 23 |

| AFS-I-alr4893 | SpR/SmR | alr4893::SpR/SmR | Gene interruption | Ref. 23 |

| AFS-I-alr2887 | SpR/SmR | alr2887::SpR/SmR | Gene interruption | Ref. 22 |

| AFS-PDGF-tic22 | SpR/SmR | nucA region::pJT13 | Promoter-GFP fusion | This study |

| AFS-I-tic22 petJ/anatic22 | SpR/SmR/NmR | alr0114::pJT14 pALH2 | Complementation | This study |

| AFS-I-tic22 petJ/D213R | SpR/SmR/NmR | alr0114::pJT14 pALH3 | Complementation | This study |

| AFS-I-tic22 petJ/I219R | SpR/SmR/NmR | alr0114::pJT14 pALH4 | Complementation | This study |

| AFS-I-tic22 petJ/F136G | SpR/SmR/NmR | alr0114::pJT14 pALH5 | Complementation | This study |

| AFS-I-tic22 petJ/atTic22 | SpR/SmR/NmR | alr0114::pJT14 pALH6 | Complementation | This study |

Heterologous Expression and Antibody Production

For heterologous expression of alr0114 and subsequent protein purification, a fragment encoding amino acids 32–274 was amplified with primers containing restriction sites NdeI and XhoI (supplemental Table S1), and subsequently cloned into pET21b digested with NdeI and XhoI. For inactivation of alr0114, two fragments of ∼400 bp encoding the N- and C-terminal half of alr0114 were amplified using the primers indicated in supplemental Table S1, which include XhoI/HindIII and HindIII/PstI restriction sites, respectively. Following cleavage with these restriction enzymes, the generated PCR fragments were cloned into pRL271 cut with XhoI and PstI. Subsequently, a fragment containing the Sp/Sm resistance cassette was produced by cleavage of pCSEL24 with HindIII and inserted between the two fragments. For generation of pJT13 carrying the translational fusion of the alr0114 promoter with GFP, a DNA fragment of ∼800 bp of the upstream region and the region encoding the first eight amino acids of the ORF of alr0114 and were amplified by PCR with the primers indicated in supplemental Table S1, containing PstI and AatII restriction sites. The ORF of GFP was amplified using primers containing the restriction sites AatII and EcoRI. The generated PCR fragments were cut with PstI/AatII and AatII/EcoRI, respectively, and inserted into pCSEL24 digested with PstI and EcoRI.

The coding region of anatic22 without signal sequence was cloned into pET21b (Novagen). Recombinant anaTic22 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) induced by addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at A600 = 0.6 and cells harvested 4 h after induction at 37 °C. Cell lysis and protein purification via nickel-NTA chromatography (Qiagen) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Antibodies against anaTic22 were produced by Pineda antibody service (Berlin, Germany).

Electron Microscopy

Preparation of Anabaena sp. for EM was done according to (28) with the following adaptations. 50 ml of Anabaena cell culture A750 = 1.5 was pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 × g, collected in 20 ml of fixate solution (BG11 + 2.5% glutaraldehyde) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Afterward, cells were washed two times with wash buffer (50 mm Na-cacodylat, pH 7.2, 0.4 m sucrose), and collected in 1 ml of wash buffer. Cells were mixed with 2 volumes of 2% OsO4 solution and incubated for 2.5 h at room temperature. Afterward, cells were washed two times in wash buffer. Subsequently, cells were dehydrated by incubation for 20 min in 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, and 2 × 100% ethanol and twice 20 min in propylenoxid. Afterward, cells were collected in a 1:1 mixture of propylenoxid and araldite and incubated overnight at room temperature. Cells were finally embedded in araldite and incubated overnight at 48 °C.

Pulldown Analysis of Interacting Proteins

The anaOmp85-POTRA (residues 161 to 470) with C-terminal His tag (anaOmp85-POTRA-HIS) was expressed and purified as in (16, 17). Protein in 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm NaPi, pH 7.6 was bound to Ni-NTA. The supernatant of Anabaena cells in 5 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 1 mm PMSF after opening by French pressing was incubated with the affinity matrix for 30 min. The matrix was washed (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm KCl), and proteins were eluted (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl). The efficiency of anaOmp85 binding was controlled by elution with 500 mm imidazole. The proteins were identified by mass spectrometric analysis (27).

In Vitro Analysis of anaTic22-POTRA Interaction

100 μg of purified protein (total) in 100 μl of 25 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, 250 mm NaCl, 500 mm imidazole was incubated with 0.023% glutaraldehyde for 5 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 100 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.0. 10% of the reaction was separated using a 10% SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining.

In Vivo Analysis of anaTic22-POTRA Interaction

50 ml of Anabaena culture was harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g, 5 min at 22 °C. The pellet was washed with 10 ml of PBS buffer and resuspended in PBS containing 10 ml of 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by resuspension in PBS supplemented with 0.25 m glycine. Cells were subsequently lysed by two French press cycles at 1,200 psi. The membrane was recovered by centrifugation at 87,000 × g and subsequently solubilized by incubation with 1.5% digitonin in PBS for 30 min on ice. The solution was cleared by centrifugation and diluted by addition of PBS to 0.3% digitonin (final concentration). Antibodies raised against anaOmp85 were added. After 1 h of incubation, the solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C with 25 μl of protein A-Sepharose. The matrix was washed four times with PBS with 0.3% digitonin, and bound proteins were eluted with 50 μl of 2× SDS-loading buffer. 15 μl were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The cross-linked product was excised from the gel, boiled for 30 min, and subjected to a 12% SDS-PAGE followed by blotting to nitrocellulose and immunodecoration with anaTic22 antibodies.

Crystal Structure Determination of anaTic22

anatic22 ORF (alr0114) from Anabaena sp. was cloned into pET21b (Novagen) omitting the signal sequence. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed and grown at 37 °C in LB medium, and expression was induced by addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at A600 = 0.6 and grown for 3 h. Cells were resuspended in buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 300 mm NaCl and 10 mm imidazole) and lysed using an M110 microfluidizer at 15,000 p.s.i./100 megapascal (Microfluidics). The cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation, supernatant was loaded on a HisTrap Ni-affinity column (GE Healthcare), and protein was eluted (buffer A with 250 mm imidazole). Size exclusion chromatography (S75 26/60 column, GE Healthcare) in 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, containing 200 mm NaCl was used for final purification. Crystallization was performed at 20 °C, using sitting-drop vapor diffusion with 1-μl drop size. Crystals were obtained from 1 m sodium citrate, 0.1 m CHES, pH 9.5, harvested in cryoprotectant buffer, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Seleno-methionine-labeled anaTic22 was obtained using a metabolic inhibition expression protocol (29) and crystallized from 1 m sodium citrate, 0.15 mm MgCl2, 0.1 m CHES, pH 9.5. Data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Data were integrated and scaled with HKL software (HKL Research, Inc.) and processed by standard procedures. Data reduction, free R assignment, and data manipulation were carried out with the CCP4 suite. The structure was determined by multiple anomalous dispersion phasing using SOLVE (30). Iterative model building and refinement were carried out with Coot (31) and REFMAC5 (32) and cycled with ARP (33). The structure quality was accessed using PROCHECK (34).

RESULTS

anaTic22 Is Expressed in Both Cell Types and Localized in Periplasm and Thylakoids

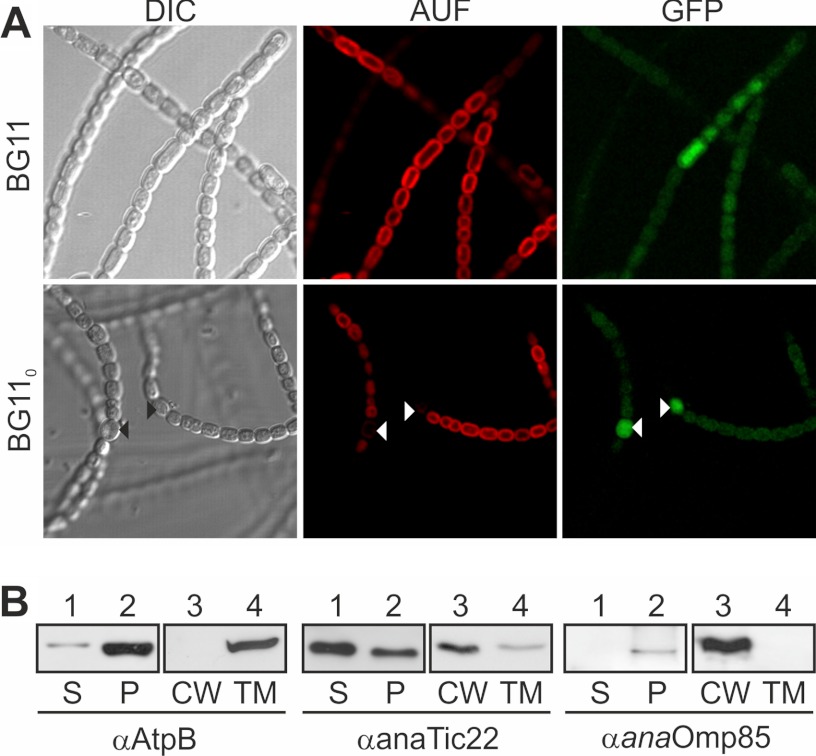

Several TOC or TIC components share a common ancestor with proteins from cyanobacteria such as Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (Anabaena sp. hereafter; Fig. 1). We analyzed Tic22, which is found in both cyanobacteria and plastids (supplemental Fig. S1). For the cyanobacterial Tic22 in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Slr0924), a periplasmic and thylakoid localization was suggested. We confirmed both results. By using a promoter GFP fusion as established previously (strain AFS-PDGF-tic22, Tables 1 and 2 and supplemental Table S1) (Fig. 2A and see Fig. 3) (22–24), we show that the promoter is active in all cells, including heterocysts (Fig. 2A, white triangle). The subcellular localization of anaTic22 was determined by fractionation of Anabaena sp. into soluble, cell wall-integrated and -associated, as well as thylakoid components. The fractionation was controlled by immunostaining against the thylakoid protein AtpB and the outer membrane protein Omp85 (Fig. 2B), which show the two fractions are not cross-contaminated. anaTic22 was identified in both, the thylakoid and cell wall fraction (Fig. 2B), indicating a dual localization in cyanobacterial cells.

FIGURE 2.

The localization of anaTic22. A, light microscopy images of Anabaena sp. mutant strain AFS-PDGF-tic22 (left) grown in BG11 (top) or BG110 (bottom), and confocal fluorescence images of the chlorophyll autofluorescence (middle) and GFP (right) are shown. Triangles mark heterocysts. B, Anabaena sp. was fractionated into soluble (S) and pellet fraction (P); the latter in cell wall (CW) and thylakoid membranes (TM). Samples were immunodecorated with indicated antibodies. AUF, autofluorescence, DIC, differential interference contrast.

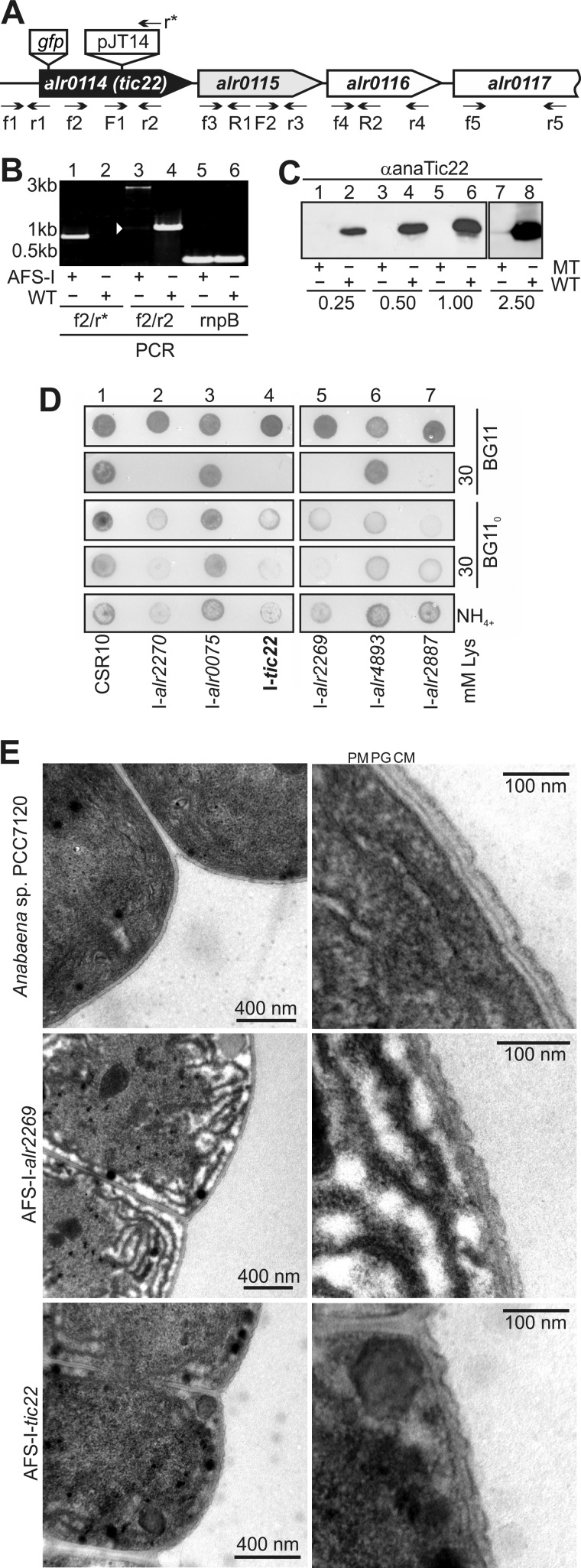

FIGURE 3.

anaTic22 is involved in OM biogenesis. A, the genomic structure of anaTic22, including downstream encoded genes, the annealing position of the oligonucleotides, the position of GFP insertion to generate strain AFS-PDGF-tic22 and the position of the plasmid insertion to generate strain AFS-I-tic22 are indicated. B, shown is the PCR on genomic DNA isolated from AFS-I-tic22 (AFS-I) and Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (WT) using the indicated primer combinations (lanes 1–4). The amplification of the rnpB region was used as loading control. C, immunodecoration of cell lysates of I-tic22 (MT, lanes 1, 3, 5) or Anabaena sp. (WT, lanes 2, 4, 6) at indicated protein amounts (mg) with anaTic22 antibodies. Loading was controlled by Ponceau staining. D, 2 μl of indicated strains (2.5 mg chlorophyll ml−1) were spotted on BG11 (panels 1 and 2), BG110 (panels 3 and 4), or BG11NH4 plates (NH4, panel 5) containing 30 mm lysozyme (panels 2 and 4; images after 7 days). E, the ultrastructure of the outer membrane of the indicated strains was analyzed by electron microscopy as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Additional images are shown in supplemental Fig. S2.

anaTic22 Performs Function in Outer Membrane Biogenesis

To analyze the function of anaTic22, we generated an insertion mutant by introducing the pJT14 into the coding region of anatic22 (Fig. 3A and Table 1) (AFS-I-tic22, I-tic22 hereafter). The cassette was inserted at base pair 403 in the middle of the coding sequence. We were unable to fully segregate the mutant, but by PCR on genomic DNA, we confirm that most of the genomic copies contained the insertion (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). However, in I-tic22, the anaTic22 protein content is reduced at least 10-fold as judged from immunodecoration with antibodies against anaTic22 (Fig. 3C), which justifies the use of the mutant for further analysis.

The phenotype of I-tic22 was compared with those of other mutants affecting OM functionality, namely mutants of Omp85 homologues (encoded by alr0075, alr4893, and alr2269 (anaomp85)), the TolC-like HgdD (alr2887) and LpxC (alr2270) involved in lipid A synthesis (22, 23). All strains grow on BG11 (Fig. 3D, panel 1). On BG110, a medium without fixed nitrogen source, all strains except the mutant of alr0075 showed reduced growth compared with a control strain (CSR10 (35)) (Fig. 3D, panel 3). With ammonium as a nitrogen source, we could further differentiate these observations, as only I-alr2270, I-alr2269, and I-tic22 were retarded in growth (Fig. 2B, panel 5). We next investigated the growth of the mutants in the presence of lysozyme to assay OM permeability (23). For I-alr2270, I-alr2269, I-alr2887, and I-tic22, we observed an enhanced sensitivity to lysozyme at concentrations of ≥30 mm as established (Fig. 3D, panels 2 and 4).

Furthermore, the insertion mutants of alr2269 and anatic22 have altered outer membrane morphology as determined by electron microscopy (Fig. 3E and supplemental Fig. S2). Using a staining method focusing on the outer membrane structure, we observed a rather smooth outer membrane structure of wild-type cells, whereas in both mutants, the outer membrane is rippled although in I-alr2269 to a larger extend. This difference was observed in all preparations (supplemental Fig. S2). In addition, the peptidoglycan layer seems to be rippled as well, which however might be the result of the alteration of the outer membrane morphology.

To confirm that the phenotype is indeed attributed to the mutation of anatic22, we analyzed whether anatic22 and alr0115 are transcribed on a common transcript in wild-type. We observed an overlapping transcript between anatic22 and alr0115, as well as between alr0115 and alr0116 (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 6). As a consequence, both genes alr0115 and alr0116 are reduced in I-tic22 as determined by RT-PCR and comparison with the transcript abundance seen in wild-type (WT, Fig. 4B, lanes 1 versus 2 and lanes 3 versus 4). The transcript abundance of alr0117 was only moderately affected (lane 5 versus 6). Thus, we complemented the mutant I-tic22 with anatic22 to confirm that the phenotype is specific to anaTic22 depletion. Indeed, the phenotype is not attributed to a malfunction of a downstream gene as complementation with anatic22 leads to a wild-type-like behavior with respect to the tested conditions (I-tic22 petJ/anatic22; Fig. 4C). These results suggest a function of cyanobacterial Tic22 in outer membrane biogenesis.

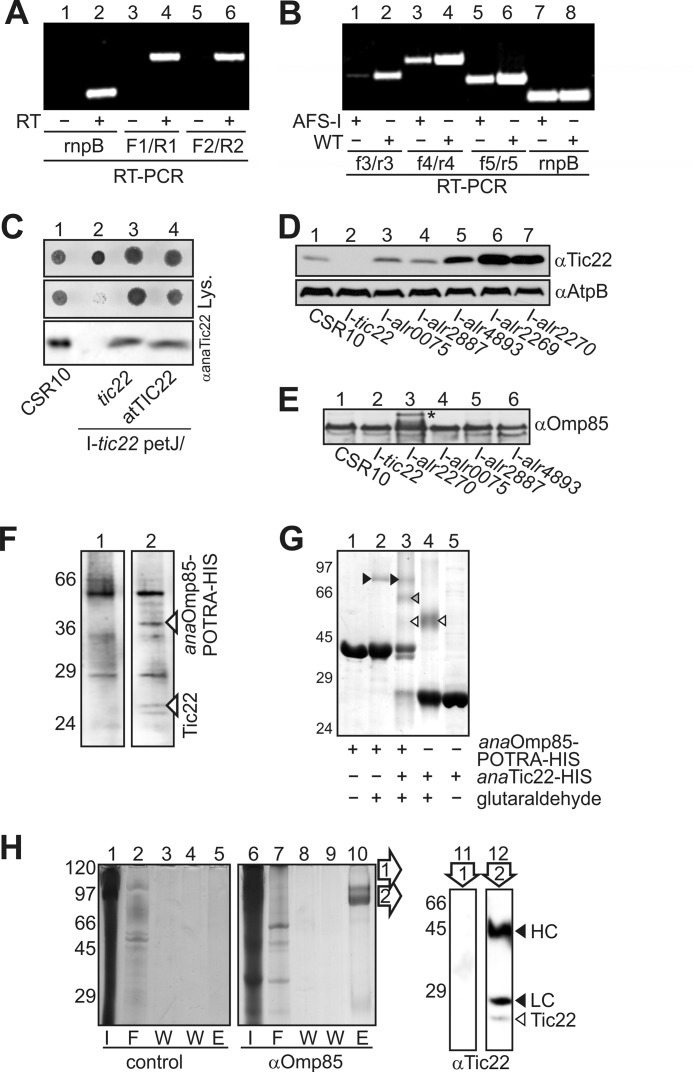

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of tic22 and alr0115 expression in the mutant. A, RNA from wild-type Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 was isolated and either rnpB or the indicated intergenic regions amplified by RT-PCR in the presence (+) or absence of reverse transcriptase (−). Primers used are indicted in Fig. 3A. B, the transcript abundance of the downstream genes was analyzed in AFS-I-tic22 (AFS-I) by RT-PCR and compared with the transcript abundance seen in WT. The combinations of oligonucleotides are indicated, and rnpB (lanes 9 and 10) was amplified as control. C, indicated strains were spotted on BG11 plates (left) with 30 mm lysozyme as described in B. For immunoblot (bottom), similar amounts of cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunodecorated with anaTic22 antibodies. D, identical amounts of cell lysate from indicated strains were subjected to immunodecoration by anaTic22 and AtpB antibodies. E, same samples as in D were subjected to immunodecoration by anaOmp85 antibodies. The cell extract from Anabaena sp. was incubated without (left) or with anaOmp85-POTRA-His (right), immobilized on NTA. Eluted protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. F, expressed anaOmp85-POTRA-His (lanes 1–3) and anaTic22-His (lanes 3–5) incubated with glutaraldehyde (lanes 2–4) was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. anaOmp85-POTRA (black), anaTic22 (white), and POTRA-anaTic22 (gray) cross-links are highlighted by triangles. G, Anabaena cells were incubated with formaldehyde, solubilized (I, lanes 1 and 6), and incubated with antibodies against anaOmp85 (lanes 7–10). After affinity purification, the flow-through (F, lanes 2 and 7), wash (W, lanes 3, 4, 8, and 9), and elution fraction (E, lanes 5 and 10) was collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. The region of lane 10 indicated (arrowheads) were excised, boiled, and subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and immunodecorated with anaTic22 antibodies (lanes 11 and 12). The migration of the heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) of the antibody (black arrowhead) and of anaTic22 (white arrowhead) is indicated.

Plant and Cyanobacterial Tic22 Are Functionally Conserved

The plant Tic22, like several other TOC or TIC components, shares a common ancestor with proteins from cyanobacteria (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). To confirm orthology, we analyzed whether atTic22-IV (AT4G33350) from Arabidopsis thaliana can complement for the anaTic22 defect in I-tic22. To this end, the cDNA of atTic22-IV was transferred into the Anabaena sp. anatic22 mutant (I-tic22 petJ/atTic22). Indeed, the expressed protein was able to complement for the growth arrest of the mutant strain at elevated lysozyme levels. Although we observed a slightly slower growth than wild-type (Fig. 4C), it confirms the functional conservation of the two proteins.

Tic22 Genetically and Physically Interacts with Omp85

The results suggest a function of cyanobacterial Tic22 in outer membrane homeostasis. Prompted by this observation, we analyzed anaTic22 abundance in the mutants mentioned above (Fig. 4D). In the mutant of alr0075 and hgdD, we observed protein levels comparable with the control strain. In the other mutants, the level of anaTic22 is significantly enhanced up to 5-fold (Fig. 4D and supplemental Fig. S3), which correlates with the observed phenotypic profile. We conclude that a disturbance of the molecular machines required for OM protein biogenesis, but not of OM in general, leads to elevated Tic22 protein levels. However, the level of anaOmp85 is not drastically affected in the anatic22 mutant (Fig. 4E), whereas in the mutant affecting lipid A synthesis (I-alr2270) Omp85 is and its precursor (*) are slightly accumulated. On the one hand, this finding suggests that Omp85 insertion into the outer membrane can bypass the Tic22 function; on the other hand, it documents that the phenotype observed for anatic22 mutants is not the result of reduced levels of anaOmp85.

To confirm the functional link, anaTic22 and anaOmp85 were tested for a direct interaction. We expressed the periplasmic-exposed POTRA domains of anaOmp85 (anaOmp85-POTRA-HIS; 24), immobilized the protein on Ni2+-NTA, and incubated it with soluble extract from Anabaena sp. We compared the elution fractions in the absence (Fig. 4F, left) or presence of anaOmp85-POTRA-HIS (Fig. 4E, right) and observed two small proteins specifically bound and not found in the control co-eluted with anaOmp85. Mass spectrometric analysis confirmed the identity of the upper band as anaTic22, whereas sequencing of the according region in the control fraction did not lead to a significant detection of a protein. Although the interaction was rather weak, the periplasmic chaperone SurA and Omp85 (BamA) of E. coli likewise showed weak interaction that had to be stabilized by chemical cross-linking (36). To confirm the proposed interaction between anaTic22 and anaOmp85-POTRA, we used a similar cross-linking approach (36).

Chemical cross-linking of purified anaOmp85-POTRA-HIS with glutaraldehyde (Fig. 4G, lane 2) stabilized the previously determined dimeric conformation (black triangle; 16). Similarly, a dimeric form of the purified anaTic22-HIS according to the migration of the cross-linked product is observed (lane 4, white triangle). However, the majority of both proteins was not cross-linked and migrated as monomer. Addition of the glutaraldehyde to a mixture of anaTic22 and anaOmp85-POTRA yielded an additional cross-link product migrating between dimeric anaTic22 and dimeric POTRA suggestive of an anaTic22-POTRA complex (lane 3, gray triangle). Interestingly, in the combination of both proteins the majority of anaTic22 was cross-linked.

In parallel, we probed for an interaction in vivo by chemical cross-linking using intact cells, followed by cell fractionation and immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4H). Using antibodies specific for anaOmp85, we observed an elution profile distinct from the control precipitation (lane 5 versus 10). After excising the bands from the gel and cleaving the cross-link by boiling, the proteins were immunodecorated with anaTic22 antibodies. In the upper band determined by anaOmp85-based precipitation, we could not detect anaTic22 (lane 11), whereas in the second band, we identified anaTic22 (lane 12). The latter confirms that anaTic22 was precipitated by anaOmp85 antibodies after cross-linking. However, the major band detected in the Coomassie staining was the anaOmp85 antibody as the heavy and light chain was stained with the secondary antibodies as well. Thus, the mass spectrometric analysis (Fig. 4F), the in vitro analysis (Fig. 4G), and the in vitro cross-linking (Fig. 4H) strongly support the existence of the physical interaction between anaTic22 and anaOmp85.

anaTic22 Has Symmetric Butterfly Structure

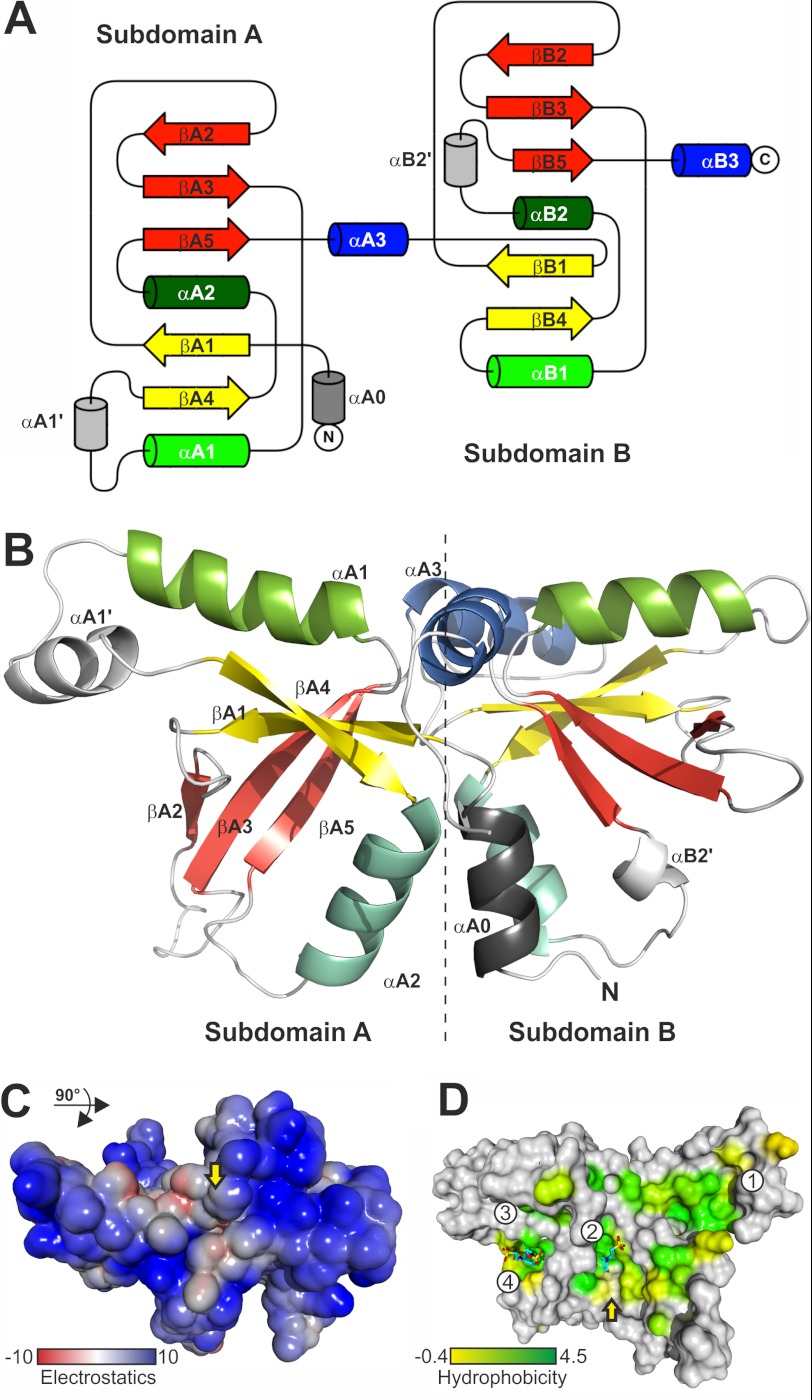

To gain further insights into the function of Tic22, we determined the three-dimensional crystal structure of anaTic22. The crystallographic structure was solved by multiple anomalous dispersion using seleno-methionine-modified protein (supplemental Table S2). anaTic22 adopts a symmetric structure (Fig. 5, A and B) with two domains (A and B) of mixed αβ topology. The two domains are nearly symmetrical with the N-terminal domain comprising 122 amino acids and the C-terminal domain 104 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 5, A and B). Each domain contains a central β-sheet with five β-strands and two interspersed helices α1 and α2 (Fig. 5, A and B). Structural variations between the two subdomains are observed with respect to loop lengths, and a short helix (αB2′) is inserted in the C-terminal domain between α2 and β5. In the N-terminal domain, a short helix (αA1′) is inserted between α1 and β4 and a helix (αA0) precedes the domain at the N terminus. Helices α1 and α3 from both domains form a cross-like arrangement with all four helices oriented almost perpendicular to each other (Fig. 5B). The pocket at the four-helix cross provides an electrostatic potential of mixed character (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

The structure of anaTic22. A, the topology diagram of anaTic22 is shown, indicating the general fold and its symmetry. B, the anaTic22 structure contains two domains with a central β-sheet of five β-strands (yellow and red) and helices α1 (light green), α2 (turquoise), and α3 (blue). Elements of domain A and unique elements in domain B are labeled. C, surface representation, rotated by 90° with respect to A shows the electrostatic potential of the solvent accessible surface (kJ/mol) of anaTic22 calculated considering implicit solvent and counter ions (54). D, the average hydrophobicity (55) of each column in the alignment of cyanobacterial Tic22 proteins (supplemental Table S3) is shown on the molecular surface with coloring from 4.5 (Ile, dark green) to −0.4 (Gly, yellow), and positions more hydrophilic (<−0.4; gray). Solvent molecules are shown as sticks.

anaTic22 Surface Exposes Functionally Relevant Hydrophobic Pockets

A tunnel runs through the protein at the binding interface of the two subdomains, which is interrupted by a septum resulting in two funnel-like pockets. The residues forming the septum are of conserved hydrophobic character (Fig. 5D and supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). In addition, the anaTic22 structure shows several distinct hydrophobic and conserved surface pockets and patches (Fig. 5D and supplemental Fig. S6). Interestingly, the hydrophobic “path” surrounding the anaTic22 structure is comparable with the substrate binding cleft of the tetrameric SecB, a cytosolic chaperone recognizing a broad signature enriched in aromatic and basic residues (37–39). Similarly, the periplasmic chaperone SurA from E. coli contains a hydrophobic surface optimized to bind sequences enriched in aromatic residues (40).

Two of the identified hydrophobic pockets (Fig. 5D, pockets 2 and 4) are occupied by zwitterionic buffer compounds with a hydrophobic cyclohexyl ring. These occupancies correlate with the dependence on the presence of CAPS or CHES buffer in the formulation for successful crystallization. The electron density observed in pocket 2 could be unambiguously fitted with a cyclohexyl ring bound in the hydrophobic pocket, whereas the charged sulfonic acid side chain protrudes into solvent. Electron density in pocket 4 (Fig. 5D) shows the buffer molecule similarly positioned as in pocket 2.

Thus, we analyzed the potential functional relevance of the hydrophobic pockets by replacement of amino acid thought to manipulate the pocket properties based on simple surface inspection (Fig. 6A). We expressed anaTic22 with aspartic acid 213 substituted by arginine (pocket 2), isoleucine 219 by arginine, and phenylalanine 136 by glycine (both pocket 3) in I-tic22 (Fig. 6B). Growth of I-tic22 complemented with anaTic22F136G in the presence of lysozyme is comparable with I-tic22 petJ/anatic22 (Fig. 6C), whereas the other two mutants did not complement for the loss of wild-type anaTic22 (Fig. 6C). The observed complementation of the Phe-136 mutant is consistent with the variability at this position (supplemental Fig. S5). In contrast, the failed complementation of I-tic22 with the other two mutants points to an important function of the surface pockets.

FIGURE 6.

Conserved functional pockets of anaTic22. A, surface representation of anaTic22 with coloring of elements conserved in plants and cyanobacteria (min 70%; supplemental Fig. S6). The proposed influence of point mutations is shown for regions framed by replacing the according amino acids. B, CSR10, I-tic22, and I-tic22 transformed with anatic22 variants were grown in BG11 and proteins immunodecorated with indicated antibodies. C, 2 μl of the strains (2.5 mg chlorophyll ml−1) were spotted on BG11 plates (lane 1) containing 30 mm lysozyme (lane 2) and grown for 7 days.

DISCUSSION

Importance of Cyanobacterial Tic22

The observed defect in the ultra-structure of the outer membrane observed in the mutants with dysfunctional anaOmp85 and anaTic22 strongly suggests a function of the two proteins in the outer membrane biogenesis of Anabaena sp. PCC7120 (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S2). This result is consistent with the fragmentation phenotype observed for I-alr2269 (23). Interestingly, anatic22 is more strongly expressed in heterocysts than in vegetative cells under diazotrophic conditions as judged from the promoter GFP fusion expression (Fig. 2). In contrast, omp85 genes do not show an enhanced expression (23), which might either be a explained by the existence of three distinct genes coding for Omp85-like proteins (23) or by an anyhow very high expression and protein content of this factor (27, 41). The enhanced expression of anatic22 during heterocyst development parallels the observation that the insertion mutant of anatic22 does not grow under these conditions (Fig. 3). This could suggest that heterocyst formation requires an alteration of the outer membrane proteome. However, the reorganization of the cell wall during heterocyst formation is not accompanied with significant proteome change in terms of the type of proteins (27, 41) but may with respect to the quantity of certain factors. The latter notion, however, has not been experimentally confirmed so far. However, it would be consistent with the impaired heterocyst development or function when genes are mutated, which code for secreted proteins involved in heterocyst-specific glycolipid layer and heterocyst envelope polysaccharide layer formation (summarized in Refs. 42 and 43). Thus, the outer membrane integrity appears to be central for heterocyst development, and anaTic22 is an important factor thereof.

Dual Localization of Cyanobacterial Tic22

The cyanobacterial Tic22 resides in both, the periplasm and in the thylakoid system (Fig. 2) (18, 19). Previously, it was suggested that the dual localization of the protein in Synechocystis sp. 6803 is a result of two possible translational start points (18). Remarkably, the protein from Anabaena sp. does not contain the two start points (supplemental Fig. S7). However, in Synechocystis sp. 6803, only <5% of the Tic22 protein was assigned to the periplasm, whereas the periplasmic fraction of Tic22 in Anabaena sp. appears to be significantly larger (Fig. 2). Thus, we have to conclude that the localization to the thylakoids is not strictly dependent on this additional signal, at least in Anabaena sp.

Consistent with the previous report, we could not isolate fully segregated mutants, which suggests that the protein is essential for cyanboacterial growth in general (Fig. 3; 18). However, the photosynthetic activity was reduced in the merodiploid Synechocystis strain (18), whereas we report a defect comparable with the one observed for omp85 mutants for the Anabaena sp. mutant (Fig. 3). In addition, we could not establish a significant defect of the photosynthetic activity or of the photosynthetic complexes (supplemental Fig. S7) (44). Whether the latter observation suggests a different functionality of Tic22 of the unicellular Synechocystis and of the filamentous Anabaena sp. has to be further investigated. Nevertheless, based on the similarity between synTic22 and anaTic22 with respect to the second translation point, it is tempting to assume that the importance of anaTic22 for the outer membrane biogenesis is conserved between different cyanobacteria.

Comparison between Cyanobacterial Tic22 and Proteobacterial SurA

The transfer of β-barrel proteins through the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria is assisted by the chaperone SurA (13, 40, 45), which does not exist in cyanobacteria (4). Here, we provide evidence that the periplasmic function of cyanobacterial Tic22 is linked to Omp85 (Fig. 4). The phenotype of I-tic22 with respect to OM biogenesis is alike the one of cyanobacterial omp85 (23) or proteobacterial surA or bamB mutants (46). Furthermore, SurA, BamB, and Tic22 interact with Omp85. However, anaTic22 and SurA bind more transiently to Omp85 than BamB (Fig. 4) (36, 45, 46).

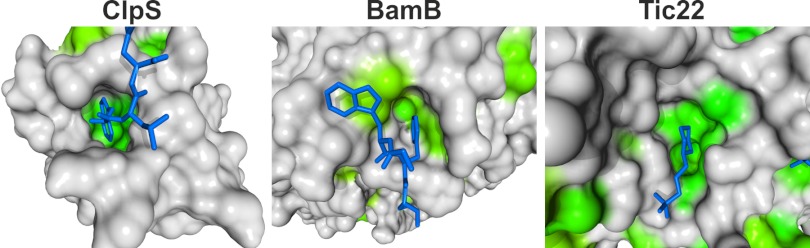

The structure of anaTic22 further supports this notion as it contains a hydrophobic surface, a property that is often found in chaperones (Fig. 5) (39, 40). These hydrophobic patches are accompanied by functional hydrophobic surface pockets (Figs. 5 and 6) similar to those found in ClpS (Fig. 7) (47). ClpS is a substrate receptor of the N-end rule pathway delivering substrates to the ClpAP protease (20). The surface pocket of ClpS is involved in the recognition of the Leu, Phe, Tyr, or Trp residues of the N-terminal degrons in the clients. In addition, BamB, a protein involved in the OMP assembly (13), has a hydrophobic pocket binding to aromatic ligands (Fig. 7) as inferred from crystal contacts (21, 48–50). Consistently, a C-terminal aromatic amino acid serves as a signal for the insertion of OMPs into the OM (13).

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the hydrophobic surface pockets of anaTic22, BamB, and ClpS. Surface of ClpS with bound tripeptide (Trp, Leu, Phe; Protein Data Bank code 3GQ1 (47)); BamB with Trp-103 and Phe-104 of a neighboring molecule (Protein Data Bank code 3PRW) (21) and pocket 2 of anaTic22 (180° rotated to C). Each amino acid is colored in green according to the average hydrophobicity (55) in the alignment (supplemental Table S3-S6) with a cut-off of 1.8 (alanine).

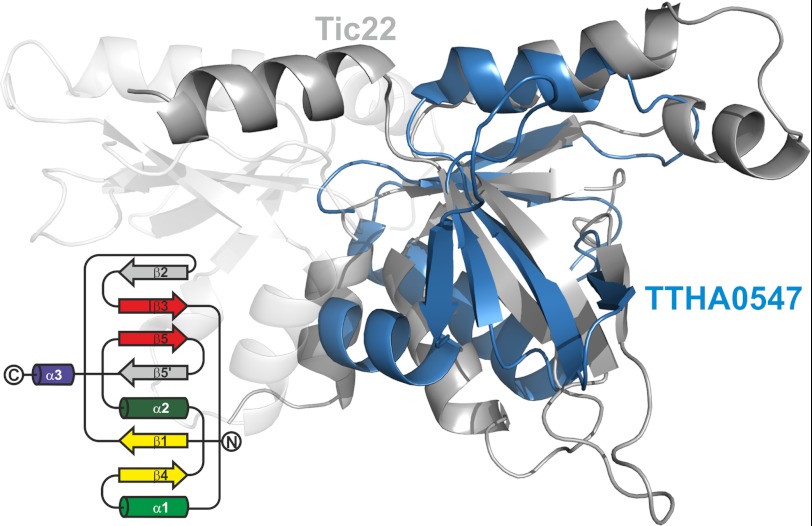

It appears that the cyanobacterial Tic22 might have a function comparable with the proteobacterial SurA. However, SurA does only exist in proteobacteria, leaving the question whether a Tic22-like protein participates in the periplasmic transfer of OMPs in other bacteria. Remarkably, by searching for structural homologues with DALI (51), we identified only one protein of unknown function from Thermus thermophilus (DALI score 4.9, Protein Data Bank code 2Z0R, TTHA0547). It resembles one subdomain, however, with notable alterations (Fig. 8) (supplemental Fig. S8). The root mean square deviation over 63 Cα positions between TTHA0547 and the subdomain A of anaTic22 amounts to 2.4 Å and to 3.2 Å over 70 Cα positions with subdomain B.

FIGURE 8.

A structural homologue in T. thermophilus. The overlay of the structure of TTHA0547 (blue) and anaTic22 (gray) is shown. The topology diagram of TTHA0547 is shown on the left.

According to the tree of life proposed by Cavalier-Smith T. thermophilus branched off from the common clade before cyanobacteria (52). Thus, the observed symmetry in the structure of the cyanobacterial Tic22 and the “single domain” structure of the protein from Thermus thermophilus points to a gene duplication event in case of the cyanobacterial protein (Fig. 5). In addition, the proteins in hado- and cyanobacteria may have a comparable function, which suggests a unifying principle in the transport of OM proteins in bacteria, whereas the molecular nature of the periplasmic chaperone differs. Thus, it will be interesting to determine the function of the T. thermophilus protein in future.

Eukaryotic Tic22 Is Inherited from Cyanobacteria

Our understanding of protein translocation across the intermembrane space of chloroplasts is sparse. Tic22 is so far the only discovered soluble intermembrane space translocon component (6, 7). The related cyanobacterial protein (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1) is distributed to both periplasm and thylakoids (Fig. 1) (18, 19), and the periplasmic localization of Tic22 appears to be evolutionarily conserved (8–10). Evidence for a functional conservation is provided by the observed complementation of the outer membrane biogenesis phenotype of the anatic22 mutant by the plant protein (Fig. 4). Similar to the proposed functional analogy between cyanobacterial Tic22 and SurA or BamB in proteobacteria, the plant Tic22 could fulfill a function comparable with the tiny Tims in the intermembrane space of mitochondria (5, 6).

Tic22 represents the second chloroplast translocation component besides Toc75 (53), for which a phylogenetic and functional relationship to the cyanobacterial homologue can be established. All other translocon components are rather products of an evolutionary “recycling” of proteins with functions distinct from protein translocation, or eukaryotic inventions (Fig. 1). Thus, although the directionality of the translocation path in plastids has been inverted, the minimal module composed of Omp85 and Tic22 is evolutionarily conserved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Wilde (Justin Liebig University, Giessen, Germany) who kindly provided antibodies against AtpB; the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility staff for support during data collection; and J. Kopp and C. Siegmann from the crystallization platform (Cluster of Excellence: CellNetworks; BZH, Heidelberg) for protein crystallization.

This work was supported by the Centre of Membrane Proteomics (Goethe University Frankfurt) (to A. H. and N. F.); the interdisciplinary Ph.D. program of Baden-Württemberg (to P. K.), the Cluster of Excellence Frankfurt (to P. K. and E. S.); the Volkswagenstiftung (to E. S.); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants TR985/1-1 (to J. T.), SFB-TR01 and SFB807 (to E. S.), and SFB638 (to I. S.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S5 and Figs. S1–S8.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4EV1) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- POTRA

- polypeptide transport-associated

- NTA

- nitrilotriacetic acid

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid

- OMP

- outer membrane protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cavalier-Smith T. (2006) Origin of mitochondria by intracellular enslavement of a photosynthetic purple bacterium. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 1943–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Archibald J. M. (2009) The puzzle of plastid evolution. Curr. Biol. 19, R81-R88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alcock F., Clements A., Webb C., Lithgow T. (2010) Evolution. Tinkering inside the organelle. Science. 327, 649–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bohnsack M. T., Schleiff E. (2010) The evolution of protein targeting and translocation systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 1115–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chacinska A., Koehler C. M., Milenkovic D., Lithgow T., Pfanner N. (2009) Importing mitochondrial proteins: Machineries and mechanisms. Cell 138, 628–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schleiff E., Becker T. (2011) Common ground for protein translocation: Access control for mitochondria and chloroplasts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 48–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kessler F., Schnell D. (2009) Chloroplast biogenesis: Diversity and regulation of the protein import apparatus. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 494–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kouranov A., Schnell D. J. (1997) Analysis of the interactions of preproteins with the import machinery over the course of protein import into chloroplasts. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1677–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kouranov A., Chen X., Fuks B., Schnell D. J. (1998) Tic20 and Tic22 are new components of the protein import apparatus at the chloroplast inner envelope membrane. J. Cell Biol. 143, 991–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Becker T., Hritz J., Vogel M., Caliebe A., Bukau B., Soll J., Schleiff E. (2004) Toc12, a novel subunit of the intermembrane space preprotein translocon of chloroplasts. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5130–5144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalanon M., McFadden G. I. (2008) The chloroplast protein translocation complexes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: A bioinformatic comparison of Toc and Tic components in plants, green algae, and red algae. Genetics. 179, 95–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hewitt V., Alcock F., Lithgow T. (2011) Minor modifications and major adaptations: The evolution of molecular machines driving mitochondrial protein import. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knowles T. J., Scott-Tucker A., Overduin M., Henderson I. R. (2009) Membrane protein architects: The role of the BAM complex in outer membrane protein assembly. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 206–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schleiff E., Maier U. G., Becker T. (2011) Omp85 in eukaryotic systems: One protein family with distinct functions. Biol. Chem. 392, 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacob-Dubuisson F., Villeret V., Clantin B., Delattre A. S., Saint N. (2009) First structural insights into the TpsB/Omp85 superfamily. Biol. Chem. 390, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ertel F., Mirus O., Bredemeier R., Moslavac S., Becker T., Schleiff E. (2005) The evolutionarily related beta-barrel polypeptide transporters from Pisum sativum and Nostoc PCC7120 contain two distinct functional domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28281–28289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koenig P., Mirus O., Haarmann R., Sommer M. S., Sinning I., Schleiff E., Tews I. (2010) Conserved properties of polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains derived from cyanobacterial Omp85. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18016–18024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fulda S., Norling B., Schoor A., Hagemann M. (2002) The Slr0924 protein of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 resembles a subunit of the chloroplast protein import complex and is mainly localized in the thylakoid lumen. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fulda S., Mikkat S., Schröder W., Hagemann M. (1999) Isolation of salt-induced periplasmic proteins from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Arch. Microbiol. 171, 214–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sriram S. M., Kim B. Y., Kwon Y. T. (2011) The N-end rule pathway: Emerging functions and molecular principles of substrate recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 735–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heuck A., Schleiffer A., Clausen T. (2011) Augmenting β-augmentation: Structural basis of how BamB binds BamA and may support folding of outer membrane proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 406, 659–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moslavac S., Nicolaisen K., Mirus O., Al Dehni F., Pernil R., Flores E., Maldener I., Schleiff E. (2007) A TolC-like protein is required for heterocyst development in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7887–7895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nicolaisen K., Mariscal V., Bredemeier R., Pernil R., Moslavac S., López-Igual R., Maldener I., Herrero A., Schleiff E., Flores E. (2009) The outer membrane of a heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium is a permeability barrier for uptake of metabolites that are exchanged between cells. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 58–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nicolaisen K., Hahn A., Valdebenito M., Moslavac S., Samborski A., Maldener I., Wilken C., Valladares A., Flores E., Hantke K., Schleiff E. (2010) The interplay between siderophore secretion and coupled iron and copper transport in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 2131–2140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. (2004) Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J. B., Herdman M., Stanier R. Y. (1979) Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Microbiology 111, 1–61 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moslavac S., Bredemeier R., Mirus O., Granvogl B., Eichacker L. A., Schleiff E. (2005) Proteomic analysis of the outer membrane of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Proteome. Res. 4, 1330–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Black K., Buikema W. J., Haselkorn R. (1995) The hglK gene is required for localization of heterocyst-specific glycolipids in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 177, 6440–6448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van Duyne G. D., Standaert R. F., Karplus P. A., Schreiber S. L., Clardy J. (1993) Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamzin V. S., Wilson K. S. (1999) Automated refinement for protein crystallography. Methods Enzymol. 276, 269–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pernil R., Picossi S., Mariscal V., Herrero A., Flores E. (2008) ABC-type amino acid uptake transporters Bgt and N-II of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 share an ATPase subunit and are expressed in vegetative cells and heterocysts. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 1067–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sklar J. G., Wu T., Kahne D., Silhavy T. J. (2007) Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 21, 2473–2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knoblauch N. T., Rüdiger S., Schönfeld H. J., Driessen A. J., Schneider-Mergener J., Bukau B. (1999) Substrate specificity of the SecB chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34219–34225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dekker C., de Kruijff B., Gros P. (2003) Crystal structure of SecB from Escherichia coli. J. Struct. Biol. 144, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bechtluft P., Nouwen N., Tans S. J., Driessen A. J. (2010) SecB–a chaperone dedicated to protein translocation. Mol. Biosyst 6, 620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu X., Wang S., Hu Y. X., McKay D. B. (2007) The periplasmic bacterial molecular chaperone SurA adapts its structure to bind peptides in different conformations to assert a sequence preference for aromatic residues. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 367–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moslavac S., Reisinger V., Berg M., Mirus O., Vosyka O., Plöscher M., Flores E., Eichacker L. A., Schleiff E. (2007) The proteome of the heterocyst cell wall in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Biol. Chem. 388, 823–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nicolaisen K., Hahn A., Schleiff E. (2009) The cell wall in heterocyst formation by Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. J. Basic Microbiol. 49, 5–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flores E., Herrero A. (2010) Compartmentalized function through cell differentiation in filamentous cyanobacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ladig R., Sommer M. S., Hahn A., Leisegang M. S., Papasotiriou D. G., Ibrahim M., Elkehal R., Karas M., Zickermann V., Gutensohn M., Brandt U., Klösgen R. B., Schleiff E. (2011) A high-definition native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system for the analysis of membrane complexes. Plant J. 67, 181–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ieva R., Tian P., Peterson J. H., Bernstein H. D. (2011) Sequential and spatially restricted interactions of assembly factors with an autotransporter β domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E383–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vuong P., Bennion D., Mantei J., Frost D., Misra R. (2008) Analysis of YfgL and YaeT interactions through bioinformatics, mutagenesis, and biochemistry. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1507–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Román-Hernández G., Grant R. A., Sauer R. T., Baker T. A. (2009) Molecular basis of substrate selection by the N-end rule adaptor protein ClpS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8888–8893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim K. H., Paetzel M. (2011) Crystal structure of Escherichia coli BamB, a lipoprotein component of the β-barrel assembly machinery complex. J. Mol. Biol. 406, 667–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Noinaj N., Fairman J. W., Buchanan S. K. (2011) The crystal structure of BamB suggests interactions with BamA and its role within the BAM complex. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 248–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Albrecht R., Zeth K. (2011) Structural basis of outer membrane protein biogenesis in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27792–27803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: Conservation mapping in three dimensions. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cavalier-Smith T. (2006) Rooting the tree of life by transition analyses. Biol. Direct. 1, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bredemeier R., Schlegel T., Ertel F., Vojta A., Borissenko L., Bohnsack M. T., Groll M., von Haeseler A., Schleiff E. (2007) Functional and phylogenetic properties of the pore-forming β-barrel transporters of the Omp85 family. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1882–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J., McCammon J. A. (2001) Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kyte J., Doolittle R. F. (1982) A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157, 105–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Olmedo-Verd E., Muro-Pastor A. M., Flores E., Herrero A. (2006) Localized induction of the ntcA regulatory gene in developing heterocysts of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6694–6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Black T. A., Cai Y., Wolk C. P. (1993) Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.