Background: NF-κB regulates BACE1 but there is little data suggesting βAPP and γ-secretase involvement.

Results: NF-κB differentially regulates Aβ production at physiological and supraphysiological Aβ concentrations by modulating transactivation of βAPP and γ-secretase promoters, thereby controlling γ-secretase activity.

Conclusion: Under physiological conditions, NF-κB regulates Aβ homeostasis while it contributes in increasing Aβ production in the pathological context.

Significance: NF-κB may be seen as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: Amyloid, Inflammation, NF-κB (NF-κB), Presenilin, Secretases, Alzheimer Disease, β-Secretase, γ-Secretase

Abstract

Anatomical lesions in Alzheimer disease-affected brains mainly consist of senile plaques, inflammation stigmata, and oxidative stress. The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a stress-activated transcription factor that is activated around senile plaques. We have assessed whether NF-κB could be differentially regulated at physiological or supraphysiological levels of amyloid β (Aβ) peptides. Under these experimental conditions, we delineated the putative NF-κB-dependent modulation of all cellular participants in Aβ production, namely its precursor βAPP (β-amyloid precursor protein) and the β- and γ-secretases, the two enzymatic machines involved in Aβ genesis. Under physiological conditions, NF-κB lowers the transcriptional activity of the promoters of βAPP, β-secretase (β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1, BACE1), and of the four protein components (Aph-1, Pen-2, nicastrin, presenilin-1, or presenilin-2) of the γ-secretase in HEK293 cells. This was accompanied by a reduction of both protein levels and enzymatic activities, thereby ultimately yielding lower amounts of Aβ and AICD (APP intracellular domain). In stably transfected Swedish βAPP-expressing HEK293 cells triggering supraphysiological concentrations of Aβ peptides, NF-κB activates the transcription of βAPP, BACE1, and some of the γ-secretase members and increases protein expression and enzymatic activities, resulting in enhanced Aβ production. Our pharmacological approach using distinct NF-κB kinase modulators indicates that both NF-κB canonical and alternative pathways are involved in the control of Aβ production. Overall, our data demonstrate that under physiological conditions, NF-κB triggers a repressive effect on Aβ production that contributes to maintaining its homeostasis, while NF-κB participates in a degenerative cycle where Aβ would feed its own production under pathological conditions.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)3 is the first cause of dementia, involving memory and cognitive deficit ultimately leading to the loss of patient autonomy (1). The molecular dysfunctions are not yet elucidated, and actual treatments are only symptomatic. AD-affected brains present extracellular deposits; the senile plaques that are mainly composed of a set of hydrophobic peptides called amyloid β-peptides (Aβ) (2). These peptides are at the center of the amyloid cascade hypothesis (3) that proposes Aβ as the main etiological trigger of the neurodegeneration taking place at late stages of the pathology (4). Therefore, a strategy aimed at circumscribing Aβ overload appears as one of the main therapeutic tracks.

Aβ is a normal product of β-amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) processing (5) that results from the sequential cleavage of βAPP by two distinct enzyme activities: the β-secretase β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and the γ-secretase that mainly consists of a high molecular weight protein complex including anterior pharynx defective-1 (Aph1), presenilin enhancer-2 (Pen2), presenilin 1 or 2 (PS1, PS2), and nicastrin (NCT) (6).

Several lines of evidence suggest that inflammation and oxidative stress could contribute to AD pathology (7, 8). This may influence Aβ production to some extent, since BACE1 expression appears to be modulated by stress (9, 10). Oxidative stress and inflammation are characterized by the release of cytokines and by reactive oxygen species, known to activate the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (11, 12).

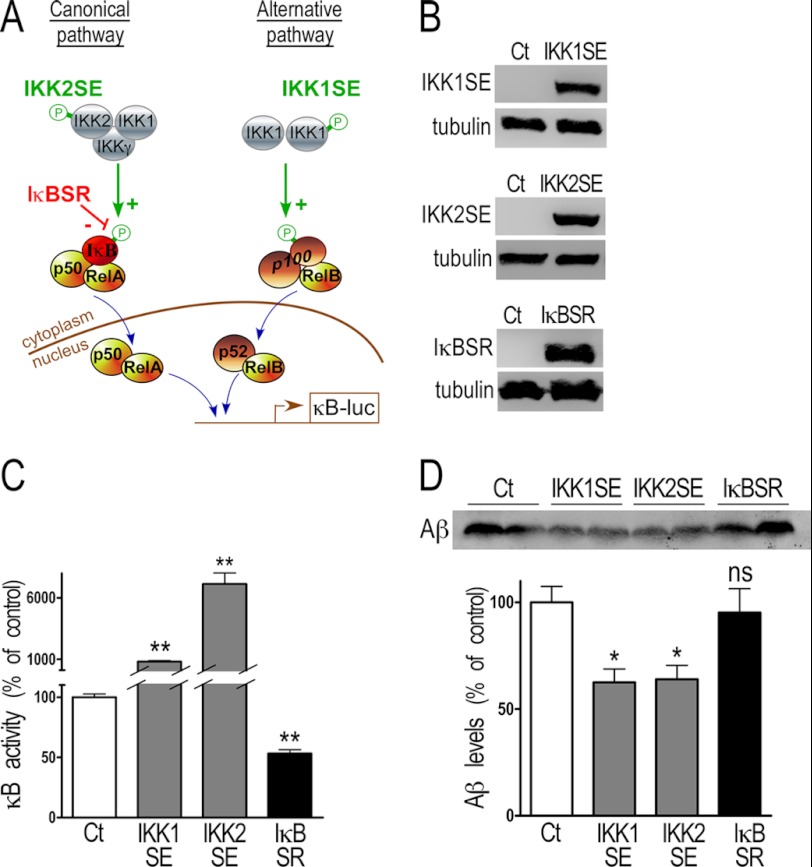

NF-κB is a dimeric transcription factor, the family of which is composed by the proteins p50, p52, p65(RelA), RelB, and c-Rel (13, 14). Two pathways have been delineated for NF-κB activation, the canonical and the alternative pathways. They are generally associated with distinct triggers, involve different signaling proteins, and are linked to structurally and functionally varying DNA-binding dimers (14) (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, an increase of NF-κB expression is observed in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of AD patients, two cerebral areas altered in this pathology (15).

FIGURE 1.

NF-κB inhibition of Aβ secretion in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. A, NF-κB is a dimeric transcription factor sequestered in the cytoplasm by the binding of its inhibitor IκB (inhibitor of κB) or p100. The pathway is activated by phosphorylation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. In the canonical pathway, NF-κB dimers, mainly p50-RelA, are bound to IκB. When the pathway is activated, IKK2 phosphorylates IκB, which dissociates from NF-κB. Free dimers of NF-κB translocate to the nucleus and regulate the expression of target genes. In the alternative pathway, IKK1 phosphorylates the inhibitory p100 subunit, p100 is processed into p52, and the dimer p52-RelB translocates to the nucleus. IKK1SE and IKK2SE are constitutively activated IKKs, and their transfection enhances IκB and p100 phosphorylation and subsequent NF-κB activation. IκBSR is a dominant negative IκB that cannot be phosphorylated, and its transfection blocks the canonical NF-κB pathway by sequestering the specific dimers in the cytoplasm. B and C, 30 h after transient transfection of IKK1SE, IKK2SE, and IκBSR, HEK293 cells were collected. The efficiency of the transfection is established by Western blot (B) as described under “Material and Methods.” The functional effect of the transfection is measured by co-transfection with κB-luciferase, a consensus sequence of fixation of the various dimers of NF-κB in-frame with luciferase (C). Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 16–20 independent determinations. **, p < 0.001. D, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) constructions, and the secreted Aβ was detected after immunoprecipitation with FCA3340 antibody and Western blotting as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to the densitometric analysis of secreted Aβ immunoreactivity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 5–6 independent determinations. *, p < 0.01; ns, not statistically significant.

Several in vitro studies suggested that NF-κB could be activated by Aβ peptides in primary cultured neurons (16, 17). This observation is indirectly consistent with the fact that NF-κB has been observed in cells surrounding or within the amyloid plaques (16–19). These studies report on an activation of the canonical pathway (16–19) involved in a feedback control by which Aβ activates NF-κB, which, in turn, regulates the production of Aβ peptides (17, 19).

Interestingly, the inhibition of NF-κB activation reduces Aβ secretion in vitro (20–22), and it was suggested that this could occur by interfering with βAPP processing (22–27). In this context, it is noteworthy that we and others previously showed that NF-κB mediated the Aβ-associated increase of BACE1 transcriptional activity (28, 29) but to date, there is relatively little data concerning the putative control of the γ-secretase build-up and activity or on the expression of βAPP by NF-κB; and, if so, if this control may be dependent on Aβ.

Here we show an Aβ concentration-dependent control of βAPP and of the members of the γ-secretase complex by NF-κB. We establish that under physiological conditions, NF-κB lowers Aβ production by repressing the protein βAPP and the β- and γ-secretase activities at a transcriptional level. Conversely, at supraphysiological concentrations of Aβ aimed at mimicking the pathological situation, NF-κB activates Aβ production by increasing βAPP and processing enzyme activities. This set of data delineates a differential control of βAPP, and β- and γ-secretases by NF-κB that depends upon physiological or supraphysiological conditions of Aβ production. Thus, our results indicate that NF-κB could normally control Aβ homeostasis in physiological conditions or contribute to a degenerative cycle by which Aβ feeds its own production in the pathological context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transfections

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells stably overexpressing empty pcDNA3.1 vector, wild-type (wt-βAPP), or βAPP harboring the Swedish double mutation (K670N/M671L; Sw-βAPP) were obtained and cultured as described previously (30). Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (CRL-2266, ATCC) were cultured following the manufacturer's instructions. SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing pcDNA3.1 or Sw-βAPP were generated following standard protocols and maintained in the presence of 400 μg of geneticin (Invitrogen). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) cells devoid of the βAPP gene (βAPP−/−) were kindly provided by Dr. U. Muller (31). Transient and stable transfections of cDNAs were obtained with jetPRIME reagent (Polyplus) with an optimized protocol (half quantities of cDNAs, buffer, and reagent recommended by the manufacturer were used). Cells were collected 30 h or 48 h after transient transfection, or selected with geneticin antibiotic (Invitrogen) to obtain stable transfection.

Activation and Inhibition of NF-κB

NF-κB was activated by transfection of HA-tagged-IKK1S>E cDNA (IKK1SE, mutations S176E and S180E on the IKK1 kinase) and Flag-tagged-IKK2S>E cDNA (IKK2SE, mutations S177E and S181E on the IKK2 kinase), and inhibited by transfection of IκB superrepressor (Myc-tagged IκBSR cDNA, mutations S32A and S36A on IκB) (32, 33). Their expression was verified by Western blot using mouse monoclonal anti-HA (Eurogentec), anti-Flag (Sigma), and anti-Myc 9E10 (given by Dr. Luc Mercken) antibodies, respectively (Fig. 1B). Their functionality was verified by cotransfection with κB-luciferase, a consensus sequence of fixation of the various dimers of NF-κB in-frame with luciferase (Fig. 1, A–C). Cells were then lysed and assayed as described below for transactivation of promoters.

Exogenous Aβ Treatment

Twenty-four hours after transfection of the κB-luciferase construct, the medium was replaced with Opti-MEM medium (Sigma) containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 10 μm phosphoramidon to prevent Aβ degradation. Cells were treated for 48 h with 0.3, 1, or 3 μm synthetic Aβ42 (Bachem).

Inhibition of γ-Secretase Activity

Thirty hours after transfection of the κB-luciferase construct, cells were treated for 18 h with 100 μm DFK167 (34) or a corresponding amount of Me2SO.

Transactivation of Promoters

cDNA encoding human promoters of βAPP (given by Dr. D. Lahiri), Aph1, Pen2, NCT (given by Dr. X. Xu), PS1 (given by Dr. M. Vitek), PS2 (given by Drs. P. Renbaum and E. Levy-Lahad), and rat promoter of BACE1 (given by Dr. S. Rossner) in-frame with luciferase were co-transfected with β-galactosidase transfection vector, to normalize transfection efficiency. CMV-β-galactosidase construction was used to assess putative artifactual effect of IKK1SE, IKK2SE, and IκB constructions on the CMV promoter. 30 h after transfection, cells were harvested with phosphate-buffered saline/EDTA (5 mm), pelleted by centrifugation 5 min at 1000 × g, lysed with 50 μl of lysis buffer (luciferase kit Promega), centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 × g. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were then analyzed as previously described (35), and protein concentration determined to normalize the luciferase activity.

Western Blotting Analysis and Antibodies

Cells were collected 48 h after transfection and lysed with the following buffer (Tris-HCl 1 m pH 7.5, NaCl 150 mm, EDTA 5 mm, Triton X-6100 0.5%, deoxycholate 0.5%). Equal amounts of proteins (70 μg) were separated on 10% (βAPP, BACE1, PS1, PS2, NCT) Tris/glycine gel acrylamide, and 16.5% Tris/tricine gels (Aph1, Pen2), and were transferred to Hybond-C membranes (Amersham Biosciences Pharmacia Life Science). Membranes were blocked with nonfat milk and incubated overnight with the following antibodies: anti-βAPP 2H3 (provided by Dr. D. Schenk, Elan Pharmaceuticals), anti-BACE1 (Abcam), anti-Aph1 O2C2 (36), anti-Nter Pen2 (Calbiochem), anti-Nter PS1 Ab14 (36), anti-C-terminal fragment-PS2 (37), anti-Nicastrin (Sigma), anti-β-tubulin, and anti-β-actin (Sigma). Immunological complexes were revealed with anti-mouse peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences Pharmacia Life Science; βAPP, BACE1) or anti-rabbit peroxidase (Immunotech; γ-secretase members proteins) antibodies. Electrochemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) was recorded as described (35), and data were processed with Multi Gauge software (Fujifilm).

BACE1 Fluorimetric Assay

Cells were collected 30 h after transfection and lysed with 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, then homogenates were monitored for their BACE1 activity as described previously (38, 39). Briefly, samples (30 μg of proteins in 25 mm acetate buffer, pH 4.5) were incubated in a final volume of 100 μl of the above acetate buffer containing BACE1 substrate (10 μm (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl-SEVNLDAEFR K(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-RRNH2; R&D Systems) in the absence or presence of β-secretase inhibitor I (50 μm, PromoCell). BACE1 activity corresponds to the β-secretase inhibitor-sensitive fluorescence recorded at 320 and 420 nm as excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. The slopes of the initial linear phase were calculated and expressed as fluorimetric units/mg/h.

In Vitro γ-Secretase Assay

48 h after transfection, cells were used for an in vitro γ-secretase assay developed in the laboratory (40). Briefly, cells were lysed with Tris 10 mm, pH 7.5, and membranes were isolated by centrifugation (22,000 × g for 1 h). An equal amount of membranes was incubated overnight with a Flag-tagged quenched fluorimetric substrate (JMV2660) mimicking the βAPP sequence targeted by γ-secretase. The products Aβ and AICD-Flag were detected by Western blotting on a 16.5% Tris/tricine gel and revealed simultaneously with anti-Aβ 2H3 and anti-Flag antibodies, respectively.

Analysis of Aβ40 Production

30 h after transfection, cells were allowed to secrete Aβ in Optim-MEM medium (Sigma) for 16 h, in the presence of 10 μm phosphoramidon to prevent Aβ degradation. The culture media were collected, supplemented with RIPA buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, EDTA 5 mm, NaCl 150 mm), and incubated overnight with a 100-fold dilution of FCA3340 (41). Aβ40 was precipitated with protein A-Sepharose (Invitrogen), Western blotted on a 16.5% Tris/tricine gel, and revealed with anti-βAPP 2H3 (provided by Dr. D. Schenk, Elan Pharmaceuticals). Cells were collected, and protein concentration was determined in order to normalize Aβ secretion.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) using either the unpaired Student's t test for pairwise comparison or the Tukey multiple comparison test for one-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

NF-κB Reduces Aβ Secretion, βAPP and Secretase Expressions and Activity in Physiological Conditions

Two pathways have been described for the activation of the transcription factors NF-κB (Fig. 1A). In canonical and alternative pathways (Fig. 1A), inactive NF-κB dimers are sequestrated in the cytoplasm either by IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) or p100, respectively. The phosphorylation of IκB or p100 by distinct IκB kinase (IKK) complexes releases active NF-κB dimers that translocate into the nucleus where they regulate the transcription of their target genes (13). The contribution of these highly regulated cascades can be selectively evaluated by means of mutant inhibitory or activating constructions, respectively, targeting IκB or upstream IKK1 or IKK2 kinases (Fig. 1A). Thus, IKK1SE and IKK2SE are constitutively activated IKKs, the transfection of which (Fig. 1B) leads to drastic increases of NF-κB activity (respectively +715.0 ± 72.6% and +7039.0 ± 899.3% compared with control, n = 20, Fig. 1C) via constitutive phosphorylation/inactivation of IκB. Conversely, IκB superrepressor (IκBSR) does not undergo phosphorylation and therefore, its overexpression lowers NF-κB activity (−46.8 ± 3.2% compared with control, n = 16, Fig. 1C). By means of these constructions, we establish that NF-κB activation reduces endogenous Aβ secretion (−37.5 ± 6.3% and −35.9 ± 6.5% for IKK1SE and IKK2SE-expressing cells, respectively, n = 5–6, Fig. 1D) while IκBSR did not alter Aβ secretion (Fig. 1D). Our results indicate that both canonical and alternative NF-κB-mediated pathways exert a negative modulation of physiological Aβ secretion in HEK293 cells.

The above data do not delineate the targets of NF-κB underlying this phenotype. At first sight, it was reasonable to envision that either the precursor of Aβ was lowered or alternatively, that the βAPP-cleaving enzymes expression and/or activities yielding Aβ could have been down-regulated. In this context, we examined whether modulation of NF-κB could influence the promoter transactivation, expression, and activity of βAPP, BACE1, as well as the components of the γ-secretase high molecular weight complex (Aph-1, Pen-2, nicastrin, PS1, or PS2).

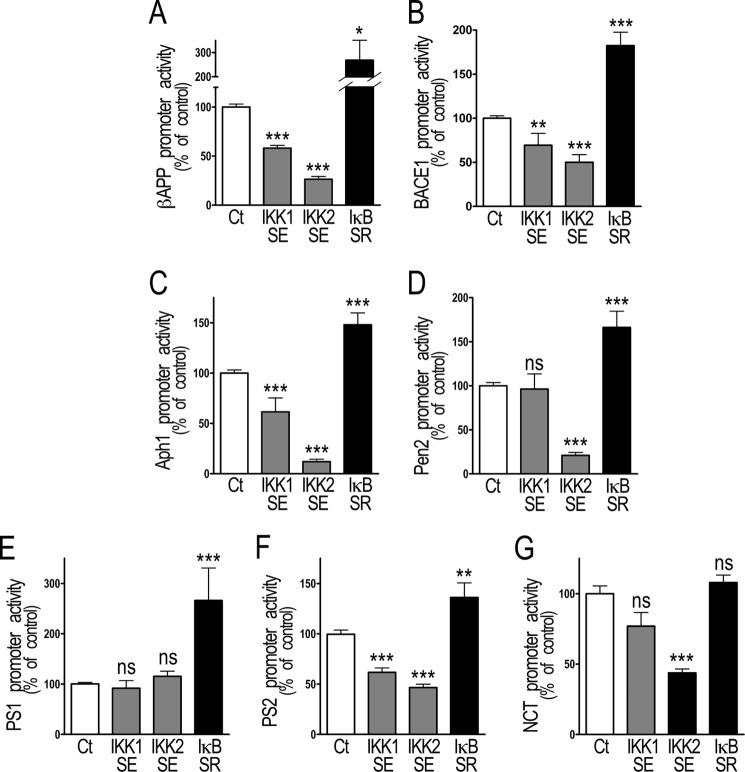

NF-κB activation by IKK1SE and IKK2SE reduces the transactivation of the promoters of βAPP (-41.9 ± 2.8% and −73.6 ± 2.8%, respectively, n = 9–10, Fig. 2A), BACE1 (−30.7 ± 13.4% and −50 ± 8.6%, n = 10–16, Fig. 2B), Aph1 (−38.4 ± 13.7% and 88.0 ± 2.4%, n = 10–16, Fig. 2C) and PS2 (38.3 ± 4.4% and 53.4 ± 3.4%, n = 12–15, Fig. 2F) while the promoters of Pen2 (79.1 ± 3.4%, n = 12, Fig. 2D) and nicastrin (56.2 ± 2.8%, n = 13, Fig. 2G) are only selectively altered by IKK2SE overexpression. PS1 promoter activity (Fig. 1E) is not affected by NF-κB activation but drastically potentiated by IκB repression (+166.2 ± 64.6% of control value, n = 15, Fig. 2E) as is observed for βAPP (+167.9 ± 82.9%, n = 14, Fig. 2A), BACE1 (+82.4 ± 15.3%, n = 11, Fig. 2B), Aph1 (+47.9 ± 11.9%, n = 11, Fig. 2C), Pen2 (+66.2 ± 18.4%, n = 11, Fig. 2D) and PS2 (+36.0 ± 14.6% n = 10, Fig. 2F), while nicastrin promoter remains unchanged (Fig. 2G).

FIGURE 2.

NF-κB inhibition of the transactivation of βAPP, BACE1, and γ-secretase promoters in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA and the promoters of βAPP (A), BACE1 (B), and γ-secretase protein components (C–G). 30 h after transfection, luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 9–22 independent determinations. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant.

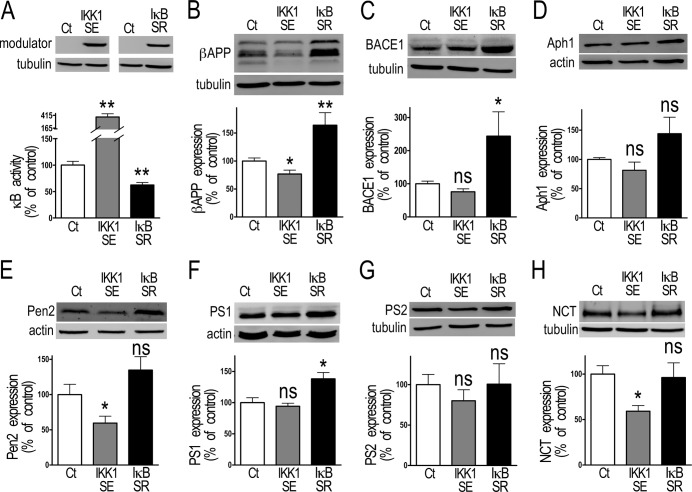

We have confirmed this data in stably transfected cells. First, as expected, stable expression of IKK1SE and IκBSR (Fig. 3A), increases (+283.8 ± 62.9%, n = 18 Fig. 3A) and reduces (−37.5 ± 4.7% n = 18, Fig. 3A) NF-κB activity, respectively. It should be noted here that our attempt to stably overexpress IKK2SE failed due to transfectant lethality upon selection procedure. Most of the proteins examined are inhibited by NF-κB in stably transfected cells (Fig. 3, B–H). Thus, IKK1SE reduces the expression of βAPP (−23.3 ± 6.9%, n = 10, Fig. 3B), Pen2 (−40.4 ± 9.8%, n = 8, Fig. 3E), and NCT (−40.9 ± 6.2%, n = 10, Fig. 3H) while conversely, the inhibition of NF-κB by IκBSR increases the expression of βAPP (+63.9 ± 22.5%, n = 6, Fig. 3B), BACE1 (+143.8 ± 73.2%, n = 6, Fig. 3C) and PS1 (+38.2 ± 10%, n = 6, Fig. 3F). Aph-1 and PS2 expression is unchanged upon NF-κB modulation in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3, D and G).

FIGURE 3.

NF-κB inhibition of βAPP, BACE1, Pen2, PS1, and nicastrin protein expression in stably transfected HEK293 cells. A, HEK293 cells were stably transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA as described under “Material and Methods.” The efficiency of the transfection is established by Western blot, and the functional effect of the transfection is measured by co-transfection with κB-luciferase in-frame with luciferase. Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 18 independent determinations. **, p > 0.001. Expression of βAPP (B), BACE1 (C), and indicated members of the γ-secretase complex (D–H) were measured in those stably transfected HEK293 cells by Western blot as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to protein expression expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 5–11 independent determinations. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ns, not statistically significant.

The above set of data obtained in transiently and stably transfected cells overall show that βAPP, BACE1, Pen2, PS1, and NCT expression is negatively regulated by NF-κB indicating that both substrates and components of enzymes involved in Aβ production are turned down by NF-κB in physiological conditions. However, our data also show that there exists a distinct NF-κB-mediated regulation of some members of the γ-secretase complex. It was therefore of prime interest to establish the functional consequence of NF-κB modulation on β-secretase and γ-secretase activities. We have taken advantage of BACE1-directed fluorimetric assay (38) and of a recently developed in vitro γ-secretase assay in reconstituted membranes (40) that allows monitoring of Aβ and AICD produced from an exogenous recombinant substrate. This permits us to directly assess whether the reduction of NF-κB on protein expression converts into an enzymatic deficiency without putative “artifactual” modulation of Aβ production via the alteration of the secretory process, βAPP trafficking, or secretase mislocalization.

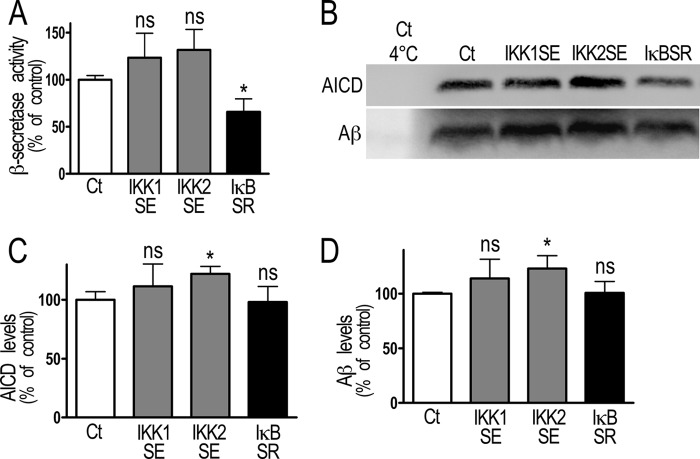

Fig. 4 shows that fluorimetric recording of β-secretase activity is increased by stable transfection of IκBSR (+100.6 ± 40.7%, n = 10, Fig. 4A) while stable transfection of the alternative pathway kinase IKK1SE did not alter it. Furthermore, AICD and Aβ productions are reduced by IKK1SE (−27.8 ± 12.8% and −26.1 ± 4.2% respectively, n = 6–8, Fig. 4, B–D) and increased by IκBSR (+77.2 ± 36.2% and +26.4 ± 7.4%, respectively, n = 6–9, Fig. 4, B–D). Overall, these data show that in physiological conditions, NF-κB-linked negative modulation of β- and γ-secretase components indeed trigger functional consequences on their enzymatic activities.

FIGURE 4.

NF-κB inhibition of β- and γ-secretase activities in stably transfected HEK293 cells. A, HEK293 cells were stably transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA and the β-secretase activity was fluorimetrically recorded as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to β-secretase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 7–10 xindependent determinations. *, p < 0.05, ns, not statistically significant. B–D, in vitro γ-secretase assays were performed in stably transfected HEK293 cells as described under “Material and Methods.” The products AICD and Aβ were detected by Western blot (B) and quantified (C and D) as described under “Materials and Methods.” Bars correspond to AICD and Aβ protein expression expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 6–7 independent determinations. *, p < 0.05.

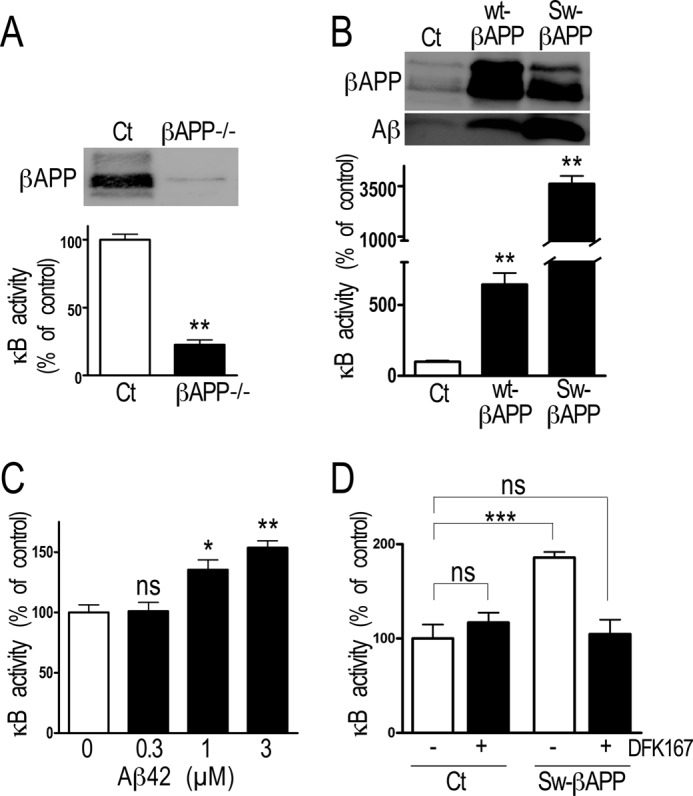

The above data show that in human cells producing endogenous levels of Aβ (Fig. 1D), NF-κB reduces βAPP expression and the proteolytic machinery involved in Aβ production. To examine whether such a phenotype is dependent on Aβ levels, we examined the NF-κB activity in varying conditions or cell systems where Aβ could be modulated. First, we established that βAPP itself or a βAPP-derived fragment indeed controls NF-κB in mouse embryonic fibroblasts since NF-κB activity is drastically lowered by βAPP depletion, (−77.4 ± 3.6%, n = 3, Fig. 5A). By contrast, in HEK293 cells overexpressing either wild-type βAPP or Swedish-mutated βAPP (42), where Aβ production is exacerbated (Fig. 5B, upper panels), NF-κB activity appears drastically enhanced (+542.6 ± 81.6% and +3521.0 ± 388.3%, respectively, n = 16, Fig. 5B). Exogenous treatment of HEK293 cells with various concentrations of Aβ42 dose-dependently increased NF-κB activity (+35.4 ± 8.2% and +53.7 ± 5.7% at 1 μm and 3 μm, respectively, n = 4, Fig. 5C). Finally, the inhibition of Aβ production by treatment of HEK293 cells with the γ-secretase inhibitor DFK167 did not modify NF-κB activity, while DFK167 prevented the Aβ-induced increase of NF-κB activity in Swedish-mutated expressing HEK293 cells (+85.7 ± 6.1%, n = 8, Fig. 5D). This suggests that only supraphysiological levels of Aβ could activate NF-κB in HEK293 cells.

FIGURE 5.

Influence of Aβ levels on NF-κB in MEF and HEK293 cells. A and B, MEF cells devoid of the βAPP gene (A), wt-βAPP and Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells (B) were transiently transfected with κB-luciferase. 30 h after transfection, luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in HEK293 mock cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of respectively 3 or 16 independent determinations, respectively. **, p < 0.001. C, 24 h after transient transfection with κB-luciferase, HEK293 cells were treated for 48 h with the indicated concentrations of synthetic Aβ42. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in non-treated cells and are the means ± S.E. of four independent determinations. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant. D, mock or Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with κB-luciferase and treated 18 h with γ-secretase inhibitor DFK167 (100 μm). 48 h after transfection, luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in nontreated HEK293 mock cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of eight independent determinations, respectively. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not statistically significant.

NF-κB Activates Aβ Secretion and Secretases Activities in Sw-βAPP HEK293 Cells

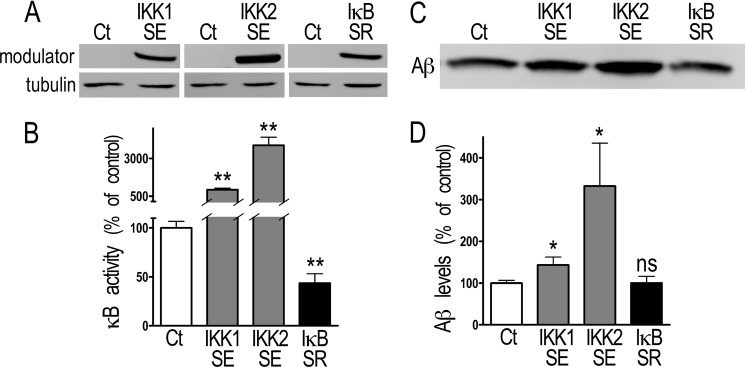

The above data led us to envision that, at supraphysiological levels of Aβ, NF-κB could function differently than under physiological conditions. We therefore manipulated NF-κB activity by transfection of its modulators in Sw-βAPP-expressing cells. First, we established that these cells display expected responsiveness to NF-κB modulation, since IKK1SE or IKK2SE expression (Fig. 6A) increases κB activity that is reduced by IκBSR (Fig. 6B). Second, unlike in naïve human cells where IKK1SE and IKK2SE reduce Aβ production (see Fig. 1D), these two kinases enhance Aβ production in Sw-βAPP cells (Fig. 6, C and D). We therefore examined whether this NF-κB-mediated increase of Aβ levels could be accounted for by a modulation of βAPP or secretase expression and/or activities. The promoter activities of βAPP, BACE1, and PS1 are activated by NF-κB (Fig. 7, A, B, E). IKK1SE and IKK2SE expression increases the promoter activity of βAPP (+30.1 ± 10.3% and +108.7 ± 26.4% respectively, n = 14–23, Fig. 7A), while IκBSR inhibits the promoter activities of BACE1 (−17.2 ± 7.3%, n = 9, Fig. 7B) and PS1 (−32.8 ± 4.1%, n = 9, Fig. 7E). The activation of BACE1 promoter was confirmed with the human construction (kindly provided by Dr. W. Song, data not shown). Aph1 promoter activity is reduced by IKK1SE (−16.2 ± 3.7%, n = 12, Fig. 7C), Pen2 promoter activity is reduced by IKK2SE (-43.3 ± 7.8%, n = 9, Fig. 7D) and increased by IκBSR (+25.0 ± 7.6%, n = 12, Fig. 7D), nicastrin promoter activity is increased by IκBSR (+33.7 ± 22.2% compared with control, n = 6, Fig. 7G) while PS2 promoter transactivation is not affected by the modulation of NF-κB activity (Fig. 7F). The examination of the changes in protein expression that could have resulted from their transcriptional modulation shows that only βAPP and Pen-2 expressions are controlled by NF-κB in Sw-βAPP-expressing cells (Fig. 8). Thus, βAPP levels are increased by IKK1SE and IKK2SE (+32.9 ± 2.8% and +106.7 ± 28.7%, respectively, n = 6, Fig. 8A) while Pen2 expression is inhibited by IKK1SE (−30.7 ± 7.0%, n = 8, Fig. 8D). The protein expression of BACE1, Aph1, PS1, PS2, and NCT is not affected by the transient transfection of the constructions in Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells. We ruled out any putative artifactual effect of IKK1SE, IKK2SE, and IκBSR on the CMV promoter driving the Sw-βAPP used for the stable transfection by means of a CMV-β-galactosidase construct. Thus, none of the above constructs affected galactosidase activity (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

NF-κB activation of Aβ secretion in transiently transfected Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells. A and B, Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA as described under “Material and Methods.” The efficiency of the transfection is established by Western blot (A), and the functional effect of the transfection is measured by co-transfection with κB-luciferase in-frame with luciferase (B). Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells and are the means ± S.E. of 9–18 independent determinations. **, p > 0.001. C and D, Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with IKK1SE, IKK2SE, or IκBSR, and the secreted Aβ was detected after immunoprecipitation with FCA3340 antibody and Western blotting as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars in D correspond to the densitometric analysis of secreted Aβ immunoreactivity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of eight independent determinations. *, p > 0.05; ns, not statistically significant.

FIGURE 7.

NF-κB activation of βAPP, BACE1, and PS1 promoter transactivations in Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells. Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with IKK1SE, IKK2SE, or IκBSR and the promoters of βAPP (A), BACE1 (B), and γ-secretase proteins (C–G). 30 h after transfection, luciferase, and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to luciferase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 9–23 independent determinations. *, p > 0.05; **, p > 0.01; ***, p > 0.001; ns, not statistically significant.

FIGURE 8.

NF-κB activation of βAPP, BACE1, and PS1 expressions in Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells. Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA and the protein expression of βAPP (A), BACE1 (B), and γ-secretase members (C–G) were measured by Western blot as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to protein expression expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 6–8 independent determinations. *, p > 0.05; **, p > 0.01; ***, p > 0.001; ns, not statistically significant.

The rather complex set of above data led us to examine as a functional integrated readout, whether in fine, β- and γ-secretase activities were modulated by NF-κB in Sw-βAPP-expressing cells. The β-secretase activity is inhibited by IκBSR (−34.1 ± 13.9%, n = 4, Fig. 9A) while the γ-secretase activity is activated by IKK2SE, as measured by the increase of AICD and Aβ expression (+22.0 ± 6.4% and +23.0 ± 11.9% respectively, n = 4–5, Fig. 9, B–D).

FIGURE 9.

NF-κB activation of β- and γ-secretase activities in Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells. A, Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA and the β-secretase activity was fluorimetrically measured as described under “Material and Methods.” Bars correspond to β-secretase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 4–6 independent determinations. *, p > 0.05, ns, not statistically significant. B and C, Sw-βAPP HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with IKK1SE, IKK2SE, or IκBSR and an in vitro γ-secretase assay was performed as described under “Material and Methods” (B) and Aβ and AICD were quantified as described under “Materials and Methods” (C and D). Bars are expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of 4–6 independent determinations. *, p > 0.05; ns, not statistically significant.

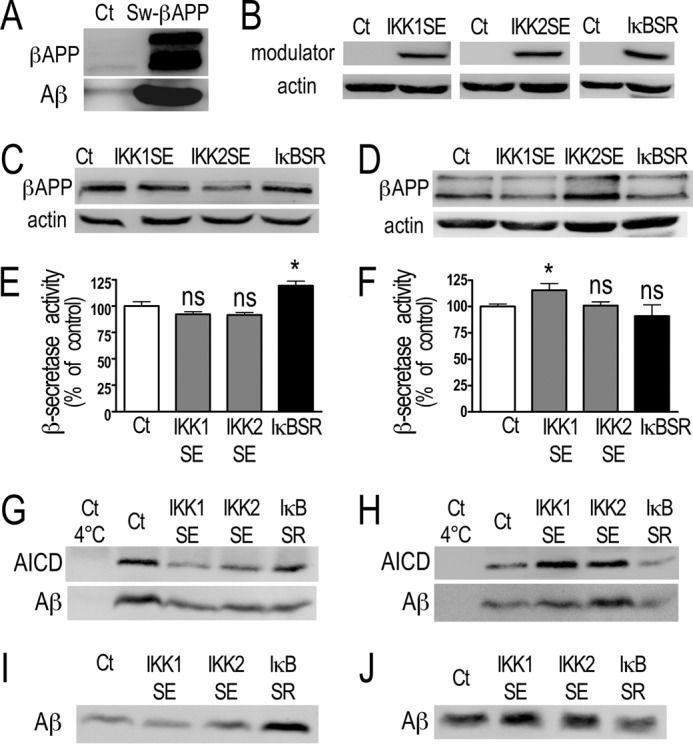

NF-κB-mediated Regulation of βAPP Expression, Secretases Activities, and Aβ Secretion under Physiological or Pathological Conditions in SH-SY5Y Cells

To assess whether NFκB-mediated control of βAPP, secretases, and Aβ production could be cell-specific, we examined the influence of NFκB modulation in a human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y cells either stably mock-transfected or expressing Sw-βAPP (Fig. 10A). Transient transfection of SH-SY5Y cells with IKK1SE, IKK2SE, or IκBSR cDNA (Fig. 10B) expectedly modulated κB-luciferase activity (supplemental Fig. S1C) but not CMV-galactosidase activity (supplemental Fig. S1D), indicating first that all the NFκB machinery taking place in HEK293 was also present in this neuronal cell line and second, that no interference of the constructs with CMV promoter occurs in these cells. NF-κB-associated pathway mediated inhibition of βAPP expression (see IKK1SE and IKK2SE lanes in Fig. 10C), β- (see IκBSR lane in Fig. 10E) and γ-secretase (see IKK1SE and IKK2SE lanes in Fig. 10G) activities and Aβ secretion (see IκBSR lane in Fig. 10I) was observed in mock-transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Conversely, in Sw-βAPP cells, NF-κB increases βAPP expression (see IKK2SE lane in Fig. 10D), β- (see IKK1SE lane in Fig. 10F) and γ-secretase (see IKK1SE and IKK2SE lanes in Fig. 10H) activities and Aβ secretion (see IKK1SE and IκBSR lanes in Fig. 10J).

FIGURE 10.

NF-κB regulation of βAPP expression, β- and γ-secretases activities and Aβ secretion in mock-transfected (Ct) or Sw-βAPP-expressing SH-SY5Y cells. Ct (C, E, G, I) or Sw-βAPP (D, F, H, J)-expressing SH-SY5Y cells (see expression of βAPP in A) were transiently transfected with NF-κB activating (IKK1SE and IKK2SE) or inhibitory (IκBSR) cDNA. 48 h after transfection cells were collected. The efficiency of the transfection (B) and βAPP expression (C and D) were measured by Western blot. The β-secretase activity was fluorimetrically recorded as described under “Materials and Methods” (E and F). Bars correspond to β-secretase activity expressed as percent of that observed in mock-transfected cells (Ct) and are the means ± S.E. of four independent determinations. *, p < 0.05; ns, not statistically significant. In vitro γ-secretase assays were performed as described under “Materials and Methods,” and the products AICD and Aβ were detected by Western blot (G and H). Secreted Aβ was detected after immunoprecipitation with FCA3340 antibody and Western blotting (I and J) as described under “Materials and Methods.”

DISCUSSION

We previously established that BACE1 promoter transactivation could be triggered by overexpression of wild-type βAPP, and to a higher extent, Sw-βAPP in human cells. This effect could be accounted for by enhanced production of Aβ, since the pharmacological inhibition and mutational inactivation of γ-secretase activity abolished the increase of BACE1 promoter transactivation while conversely, exogenous application of synthetic Aβ42 promoted this effect (29). Our study showed that Aβ42-mediated increase of BACE1 transactivation was NF-κB-dependent (29). This agreed well with a study showing that NF-κB could regulate neuronal BACE1 promoter activation (28). These data delineate a deleterious dysfunction by which overproduction of Aβ feeds its own production.

In vivo studies have suggested an NF-κB-dependent regulation of Aβ production. In transgenic mice NF-κB increases βAPP levels (43), BACE1 promoter activity (44), expression (25, 45), and enzymatic activity (25, 43), γ-secretase activity (43); and Aβ production (25, 43, 46). Furthermore, the inhibition of NF-κB reduced the plaque burden in mice (25, 44) and increased the learning and memory deficits of mice (43). However, to modulate NF-κB activity, those studies used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (46), natural compounds (25, 43) or modulation of upstream receptors of NF-κB activation pathway (44, 47), which are nonspecific to NF-κB activation. In the present study, we focused on the mechanisms of NF-κB regulation of Aβ production; thus we transfected mutant construction of the proteins that directly activate or inhibit NFκB dimers and are commonly activated by the various stimuli activating NFκB.

BACE1 produces C99 that requires subsequent cleavage by γ-secretase to yield Aβ (5). However, although NF-κB-dependent regulation of γ-secretase has been suggested (43, 48, 49), the direct regulation of the γ-secretase components by NF-κB has not been detailed. Furthermore, although two NF-κB binding sites have been delineated on the βAPP promoter, no data concern its putative control by NF-κB in pathological conditions. Our study shows that in supraphysiological conditions, NF-κB activation up-regulates some components of the high molecular weight γ-secretase complex and the βAPP protein in human cells from both renal and neuronal origin.

Our data demonstrate a coordinated regulation of the three principal elements of Aβ biogenesis, i.e. its precursor βAPP, and the two enzymatic activities β- and γ-secretases responsible for its production. We also show, strikingly, that NF-κB-dependent control of Aβ production depends on pathophysiological context, unlike the above experimental conditions aimed at mimicking the pathology. In physiological conditions, Aβ-mediated NF-κB-dependent pathway results in a consistent lowering of βAPP expression as well as β-secretase and γ-secretase members expression, ultimately leading to reduced enzymatic activity. Thus, in physiological conditions, NF-κB contributes to maintain Aβ homeostasis at a physiological level while in pathological conditions, NF-κB contributes to a vicious cycle by which Aβ self-feds its own production (Fig. 11).

FIGURE 11.

Scheme of Aβ-NF-κB interplay in physiopathological conditions. A, endogenous Aβ activates NF-κB which, in turn lowers βAPP, BACE1, and γ-secretase activity, thereby lowering Aβ. This allows maintaining Aβ homeostasis in physiological conditions. B, at high Aβ concentrations, NF-κB mostly increases βAPP and thereby increases Aβ in regulatory loop favoring exacerbated Aβ production.

It has been demonstrated that NF-κB inhibits BACE1 promoter activity in neuronal and resting glial cells while it activates BACE1 promoter in Aβ-exposed neuronal and activated glial cells (28). This can be explained by the nature of the NF-κB dimers involved since p52/c-Rel occurs in resting conditions while, p50/p65, p52/p65, and p52/c-Rel are responsible for NF-κB-mediated BACE1 transactivation in activated neurons and glia (28). In this context, it is noteworthy that Valerio et al. (17) demonstrated that Aβ40 could activate NF-κB by favoring the nuclear translocation of p50 and p65 subunits. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that the recruitment of NF-κB components and the build-up of the distinct heterodimeric complex could be related to Aβ levels. Thus, Arevalo et al. showed that a low concentration of Aβ40 triggers NGF-like phenotype while a 40-fold higher concentration prevents NGF-induced activation of NF-κB (50). Accordingly, it was reported that only low concentrations of Aβ could trigger NF-κB-dependent protective phenotype (18). This set of data support our conclusion that physiological and supraphysiological levels of Aβ could differentially contribute to its own production by modulating its precursor and secretases via an NF-κB-dependent mechanism.

Our data do not establish whether NF-κB-associated increase in promoter transcription is direct or involves intracellular intermediates. One or several consensus sequence sites have been identified on the βAPP promoter (51), human (19), and rat (28) BACE1 promoters as well as on the PS2 promoter (52) that could mediate a physical interaction between NF-κB and these promoters. An additional possibility lies on the control of the tumor suppressor p53 by NF-κB. In this matter, the literature indicates that NF-κB could either activate p53 (53) or antagonize its effect (54), leading to either antiapoptotic and/or proapoptotic phenotypes (55). Interestingly, several studies indicated that p53 represses PS1 (56–59), and we have shown that, at physiological concentrations of Aβ, p53 also lowers Pen-2 promoter transactivation (60, 61). If one accepts the view that NF-κB activates p53 (53), this agrees with our observation that in a physiological context, p53-mediated NF-κB-linked reduction of PS1, Pen-2, and other contributors of Aβ genesis (see Figs. 2 and 3) ultimately leads to decreased γ-secretase expression and activity. Alternatively, if one considers NF-κB as a repressor of p53, then one can envision that NF-κB-mediated p53-dependent effect could only occur in pathological conditions where PS1 promoter transactivation is enhanced (see Fig. 7). It is actually difficult to resolve this issue in the absence of data concerning the influence of Aβ concentration on the control of p53 by NF-κB. But there again, this presumes a differential NF-κB-p53-dependent control of Aβ in physiological and supraphysiological conditions.

NF-κB is an ubiquitous transcription factor activated by inflammation, oxidative, and others cellular stresses (11, 13). This activation results in a protective response aimed at restoring cellular homeostasis, but can be deleterious when becoming chronic. This can be compared with NF-κB-mediated control of Aβ production that protects against Aβ overload in physiological conditions while it contributes to perpetuate and even increase Aβ levels in a more pathological context.

Besides classical strategies aimed at reducing Aβ production by directly modulating either β- or γ-secretases with pharmacological probes or by neutralizing Aβ-associated effects by a vaccinal approach (62, 63), alternative therapeutic tracks targeting NF-κB could be theoretically envisioned. One of these concerns is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment. In these pathological conditions, our data show that NSAID-associated down-regulation of NF-κB could have beneficial effects on Aβ load even if deleterious side effects of interfering with NF-κB pathways should not be underestimated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. P. Fraser, L. Mercken, P. St. George-Hyslop, and T. Tabira for the antibodies, Drs. D. Lahiri, P. Renbaum, E. Levy-Lahad, S. Roβner, W. Song, G. Thinakaran, M. Vitek, and X. Xu for the promoters, and Dr. U. Muller for the cells.

This work was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), by the Conseil Général des Alpes Maritimes, and by the Ministère de l'enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche. This work has been developed and supported through the LABEX (excellence laboratory, program investment for the future) DISTALZ (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary approach to Alzheimer disease).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- AICD

- βAPP intracellular domain

- Aβ

- amyloid β-peptides

- Aph1

- anterior pharynx defective-1

- βAPP

- β-amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

- β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- wt-βAPP

- wild-type βAPP

- Sw-βAPP

- Swedish mutated βAPP

- IκB

- inhibitor of NF-κB

- IκBSR

- IκB superrepressor

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- NCT

- nicastrin

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- NSAID

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Pen2

- presenilin enhancer-2

- PS1 and PS2

- presenilin-1 and -2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Terry R. D., Davies P. (1980) Dementia of the Alzheimer type. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 77–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Selkoe D. J., Abraham C. R., Podlisny M. B., Duffy L. K. (1986) Isolation of low-molecular-weight proteins from amyloid plaque fibers in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 46, 1820–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardy J. A., Higgins G. A. (1992) Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256, 184–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suh Y. H., Checler F. (2002) Amyloid precursor protein, presenilins, and alpha-synuclein: molecular pathogenesis and pharmacological applications in Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 469–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Checler F. (1995) Processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein and its regulation in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 65, 1431–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takasugi N., Tomita T., Hayashi I., Tsuruoka M., Niimura M., Takahashi Y., Thinakaran G., Iwatsubo T. (2003) The role of presenilin cofactors in the γ-secretase complex. Nature 422, 438–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akiyama H., Barger S., Barnum S., Bradt B., Bauer J., Cole G. M., Cooper N. R., Eikelenboom P., Emmerling M., Fiebich B. L., Finch C. E., Frautschy S., Griffin W. S., Hampel H., Hull M., Landreth G., Lue L., Mrak R., Mackenzie I. R., McGeer P. L., O'Banion M. K., Pachter J., Pasinetti G., Plata-Salaman C., Rogers J., Rydel R., Shen Y., Streit W., Strohmeyer R., Tooyoma I., Van Muiswinkel F. L., Veerhuis R., Walker D., Webster S., Wegrzyniak B., Wenk G., Wyss-Coray T. (2000) Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 21, 383–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tamagno E., Guglielmotto M., Monteleone D., Tabaton M. (2011) Neurotox Res., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun X., Bromley-Brits K., Song W. (2012) J. Neurochem. Suppl. 1, 62–70, 120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vassar R., Kovacs D. M., Yan R., Wong P. C. (2009) The β-secretase enzyme BACE in health and Alzheimer's disease: regulation, cell biology, function, and therapeutic potential. J. Neurosci. 29, 12787–12794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mercurio F., Manning A. M. (1999) NF-κB as a primary regulator of the stress response. Oncogene 18, 6163–6171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgan M. J., Liu Z. G. (2011) Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB. Cell Res. 21, 103–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oeckinghaus A., Ghosh S. (2009) The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 1, a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonizzi G., Karin M. (2004) The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25, 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Terai K., Matsuo A., McGeer P. L. (1996) Enhancement of immunoreactivity for NF-κB in the hippocampal formation and cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 735, 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaltschmidt B., Uherek M., Volk B., Baeuerle P. A., Kaltschmidt C. (1997) Transcription factor NF-kappaB is activated in primary neurons by amyloid β peptides and in neurons surrounding early plaques from patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2642–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valerio A., Boroni F., Benarese M., Sarnico I., Ghisi V., Bresciani L. G., Ferrario M., Borsani G., Spano P., Pizzi M. (2006) NF-κB pathway: a target for preventing β-amyloid (Aβ)-induced neuronal damage and Aβ42 production. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 1711–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaltschmidt B., Uherek M., Wellmann H., Volk B., Kaltschmidt C. (1999) Inhibition of NF-κB potentiates amyloid β-mediated neuronal apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9409–9414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C. H., Zhou W., Liu S., Deng Y., Cai F., Tone M., Tone Y., Tong Y., Song W. (2011) Increased NF-κB signalling up-regulates BACE1 expression and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomita S., Fujita T., Kirino Y., Suzuki T. (2000) PDZ domain-dependent suppression of NF-κB/p65-induced Aβ42 production by a neuron-specific X11-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13056–13060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pandey N. R., Sultan K., Twomey E., Sparks D. L. (2009) Phospholipids block nuclear factor-κB and tau phosphorylation and inhibit amyloid-β secretion in human neuroblastoma cells. Neuroscience 164, 1744–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paris D., Patel N., Quadros A., Linan M., Bakshi P., Ait-Ghezala G., Mullan M. (2007) Inhibition of Aβ production by NF-κB inhibitors. Neurosci. Lett. 415, 11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ait-Ghezala G., Volmar C. H., Frieling J., Paris D., Tweed M., Bakshi P., Mullan M. (2007) CD40 promotion of amyloid β production occurs via the NF-κB pathway. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 1685–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sastre M., Walter J., Gentleman S. M. (2008) Interactions between APP secretases and inflammatory mediators. J. Neuroinflammation 5, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paris D., Ganey N. J., Laporte V., Patel N. S., Beaulieu-Abdelahad D., Bachmeier C., March A., Ait-Ghezala G., Mullan M. J. (2010) Reduction of β-amyloid pathology by celastrol in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation 7, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paris D., Beaulieu-Abdelahad D., Bachmeier C., Reed J., Ait-Ghezala G., Bishop A., Chao J., Mathura V., Crawford F., Mullan M. (2011) Anatabine lowers Alzheimer's Aβ production in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 670, 384–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paris D., Mathura V., Ait-Ghezala G., Beaulieu-Abdelahad D., Patel N., Bachmeier C., Mullan M. (2011) Flavonoids lower Alzheimer's Aβ production via an NFκB-dependent mechanism. Bioinformation 6, 229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bourne K. Z., Ferrari D. C., Lange-Dohna C., Rossner S., Wood T. G., Perez-Polo J. R. (2007) Differential regulation of BACE1 promoter activity by nuclear factor-κB in neurons and glia upon exposure to β-amyloid peptides. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1194–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buggia-Prevot V., Sevalle J., Rossner S., Checler F. (2008) NFκB-dependent control of BACE1 promoter transactivation by Aβ42. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10037–10047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chevallier N., Jiracek J., Vincent B., Baur C. P., Spillantini M. G., Goedert M., Dive V., Checler F. (1997) Examination of the role of endopeptidase 3.4.24.15 in Aβ secretion by human transfected cells. Br J. Pharmacol. 121, 556–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heber S., Herms J., Gajic V., Hainfellner J., Aguzzi A., Rülicke T., von Kretzschmar H., von Koch C., Sisodia S., Tremml P., Lipp H. P., Wolfer D. P., Müller U. (2000) Mice with combined gene knock-outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J. Neurosci. 20, 7951–7963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mercurio F., Murray B. W., Shevchenko A., Bennett B. L., Young D. B., Li J. W., Pascual G., Motiwala A., Zhu H., Mann M., Manning A. M. (1999) IκB kinase (IKK)-associated protein 1, a common component of the heterogeneous IKK complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 1526–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mercurio F., Zhu H., Murray B. W., Shevchenko A., Bennett B. L., Li J., Young D. B., Barbosa M., Mann M., Manning A., Rao A. (1997) IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science 278, 860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wolfe M. S., Citron M., Diehl T. S., Xia W., Donkor I. O., Selkoe D. J. (1998) A substrate-based difluoro ketone selectively inhibits Alzheimer's γ-secretase activity. J. Med. Chem. 41, 6–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. da Costa C. A., Sunyach C., Giaime E., West A., Corti O., Brice A., Safe S., Abou-Sleiman P. M., Wood N. W., Takahashi H., Goldberg M. S., Shen J., Checler F. (2009) Transcriptional repression of p53 by parkin and impairment by mutations associated with autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson's disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1370–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gu Y., Chen F., Sanjo N., Kawarai T., Hasegawa H., Duthie M., Li W., Ruan X., Luthra A., Mount H. T., Tandon A., Fraser P. E., St George-Hyslop P. (2003) APH-1 interacts with mature and immature forms of presenilins and nicastrin and may play a role in maturation of presenilin.nicastrin complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7374–7380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Araki W., Yuasa K., Takeda S., Shirotani K., Takahashi K., Tabira T. (2000) Overexpression of presenilin-2 enhances apoptotic death of cultured cortical neurons. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 920, 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Andrau D., Dumanchin-Njock C., Ayral E., Vizzavona J., Farzan M., Boisbrun M., Fulcrand P., Hernandez J. F., Martinez J., Lefranc-Jullien S., Checler F. (2003) BACE1- and BACE2-expressing human cells: characterization of β-amyloid precursor protein-derived catabolites, design of a novel fluorimetric assay, and identification of new in vitro inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25859–25866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lefranc-Jullien S., Lisowski V., Hernandez J. F., Martinez J., Checler F. (2005) Design and characterization of a new cell-permeant inhibitor of the β-secretase BACE1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 145, 228–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sevalle J., Ayral E., Hernandez J. F., Martinez J., Checler F. (2009) Pharmacological evidences for DFK167-sensitive presenilin-independent γ-secretase-like activity. J. Neurochem. 110, 275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barelli H., Lebeau A., Vizzavona J., Delaere P., Chevallier N., Drouot C., Marambaud P., Ancolio K., Buxbaum J. D., Khorkova O., Heroux J., Sahasrabudhe S., Martinez J., Warter J. M., Mohr M., Checler F. (1997) Characterization of new polyclonal antibodies specific for 40 and 42 amino acid-long amyloid β peptides: their use to examine the cell biology of presenilins and the immunohistochemistry of sporadic Alzheimer's disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy cases. Mol. Med. 3, 695–707 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Citron M., Oltersdorf T., Haass C., McConlogue L., Hung A. Y., Seubert P., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Lieberburg I., Selkoe D. J. (1992) Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases β-protein production. Nature 360, 672–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi D. Y., Lee J. W., Lin G., Lee Y. K., Lee Y. H., Choi I. S., Han S. B., Jung J. K., Kim Y. H., Kim K. H., Oh K. W., Hong J. T. (2012) Neurochem. Int. 60, 68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. He P., Zhong Z., Lindholm K., Berning L., Lee W., Lemere C., Staufenbiel M., Li R., Shen Y. (2007) Deletion of tumor necrosis factor death receptor inhibits amyloid β generation and prevents learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer's mice. J. Cell Biol. 178, 829–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guglielmotto M., Aragno M., Tamagno E., Vercellinatto I., Visentin S., Medana C., Catalano M. G., Smith M. A., Perry G., Danni O., Boccuzzi G., Tabaton M. (2010) AGEs/RAGE complex upregulates BACE1 via NF-κB pathway activation. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 113–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sung S., Yang H., Uryu K., Lee E. B., Zhao L., Shineman D., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M., Praticò D. (2004) Modulation of nuclear factor-κB activity by indomethacin influences Aβ levels but not Aβ precursor protein metabolism in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 2197–2206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guglielmotto M., Giliberto L., Tamagno E., Tabaton M. (2010) Oxidative stress mediates the pathogenic effect of different Alzheimer's disease risk factors. Front Aging Neurosci. 2, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee J. W., Lee Y. K., Ban J. O., Ha T. Y., Yun Y. P., Han S. B., Oh K. W., Hong J. T. (2009) Green tea (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits β-amyloid-induced cognitive dysfunction through modification of secretase activity via inhibition of ERK and NF-κB pathways in mice. J. Nutr. 139, 1987–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee Y. J., Choi D. Y., Choi I. S., Han J. Y., Jeong H. S., Han S. B., Oh K. W., Hong J. T. (2011) Inhibitory effect of a tyrosine-fructose Maillard reaction product, 2,4-bis(p-hydroxyphenyl)-2-butenal on amyloid-β generation and inflammatory reactions via inhibition of NF-κB and STAT3 activation in cultured astrocytes and microglial BV-2 cells. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arevalo M. A., Roldan P. M., Chacón P. J., Rodríguez-Tebar A. (2009) Amyloid β serves as an NGF-like neurotrophic factor or acts as a NGF antagonist depending on its concentration. J. Neurochem. 111, 1425–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Grilli M., Ribola M., Alberici A., Valerio A., Memo M., Spano P. (1995) Identification and characterization of a κB/Rel binding site in the regulatory region of the amyloid precursor protein gene. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26774–26777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pennypacker K. R., Fuldner R., Xu R., Hernandez H., Dawbarn D., Mehta N., Perez-Tur J., Baker M., Hutton M. (1998) Cloning and characterization of the presenilin-2 gene promoter. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 56, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu H., Lozano G. (1994) NF-κB activation of p53. A potential mechanism for suppressing cell growth in response to stress. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20067–20074 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ak P., Levine A. J. (2010) p53 and NF-κB: different strategies for responding to stress lead to a functional antagonism. FASEB J. 24, 3643–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Martin A. G. (2010) NFκB anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic, maybe both. Cell Cycle 9, 3131–3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pastorcic M., Das H. K. (2000) Regulation of transcription of the human presenilin-1 gene by ets transcription factors and the p53 protooncogene. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34938–34945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roperch J. P., Alvaro V., Prieur S., Tuynder M., Nemani M., Lethrosne F., Piouffre L., Gendron M. C., Israeli D., Dausset J., Oren M., Amson R., Telerman A. (1998) Inhibition of presenilin 1 expression is promoted by p53 and p21WAF-1 and results in apoptosis and tumor suppression. Nat. Med. 4, 835–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alves da Costa C., Paitel E., Mattson M. P., Amson R., Telerman A., Ancolio K., Checler F. (2002) Wild-type and mutated presenilins 2 trigger p53-dependent apoptosis and down-regulate presenilin 1 expression in HEK293 human cells and in murine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4043–4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alves da Costa C., Sunyach C., Pardossi-Piquard R., Sevalle J., Vincent B., Boyer N., Kawarai T., Girardot N., St George-Hyslop P., Checler F. (2006) Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase-mediated control of p53-associated cell death in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 26, 6377–6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dunys J., Sevalle J., Giaime E., Pardossi-Piquard R., Vitek M. P., Renbaum P., Levy-Lahad E., Zhang Y. W., Xu H., Checler F., da Costa C. A. (2009) p53-dependent control of transactivation of the Pen2 promoter by presenilins. J. Cell Sci. 122, 4003–4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Checler F., Dunys J., Pardossi-Piquard R., Alves da Costa C. (2010) p53 is regulated by and regulates members of the γ-secretase complex. Neurodegener Dis. 7, 50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. De Strooper B., Vassar R., Golde T. (2010) The secretases: enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Delrieu J., Ousset P. J., Caillaud C., Vellas B. (2012) J. Neurochem. 120, Suppl. 1, 186–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.