Abstract

Mitotic DNA damage is a constant threat to genomic integrity, yet understanding of the cellular responses to this stress remain incomplete. Recent work by Anantha et al. (PNAS 2008; 105:12903–8) has found surprising evidence that RPA, the primary eukaryotic single-stranded DNA-binding protein, can stimulate the ability of cells to exit mitosis into a 2N G1 phase. Along with providing additional discussion of this study, we review evidence suggesting that DNA replication and repair factors can modulate mitotic transit by acting through Polo-like kinase-1 (Plk1) and the centrosome. “A crisis unmasks everyone.”—Mason Cooley, US aphorist.

Keywords: Plk1, RPA, centrosome, mitotic DNA damage, phosphorylation, spindle assembly checkpoint

Introduction

DNA damage occurring in the period between the G2/M checkpoint and anaphase onset represents a formidable challenge to cell viability and genomic integrity. Possible repair options are restricted by chromosomal DNA condensation in preparation for cytokinesis. Furthermore, double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) generated in this ‘window of vulnerability’ have the potential to increase chromosomal mis-segregation and aneuploidy if cells proceed to anaphase and cell division. Given that tens of billions of mitoses occur daily in an adult human,1 the potential for mitotic DNA damage is appreciable. Not surprisingly, investigation of mitotic DNA damage has found that vertebrate cells employ various mechanisms to respond to this event, mechanisms that are now becoming illuminated.

A recently identified regulator of mitotic transit under genotoxic stress conditions is replication protein A (RPA).2 RPA is a heterotrimeric single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein that is essential for DNA replication and recombination, as well as for a variety of DNA repair reactions.3 So what then is RPA doing during mitosis? Along with addressing this question, we will broaden the review to also discuss other replication/repair factors, a handful of which have recently been implicated in having a role in regulating mitotic progression.

RPA Activity in Mitosis

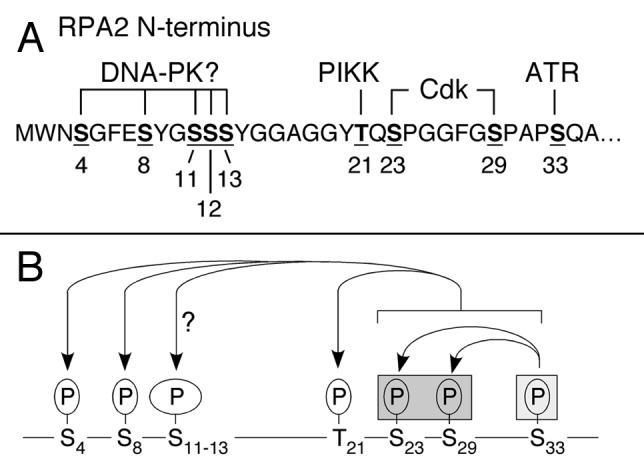

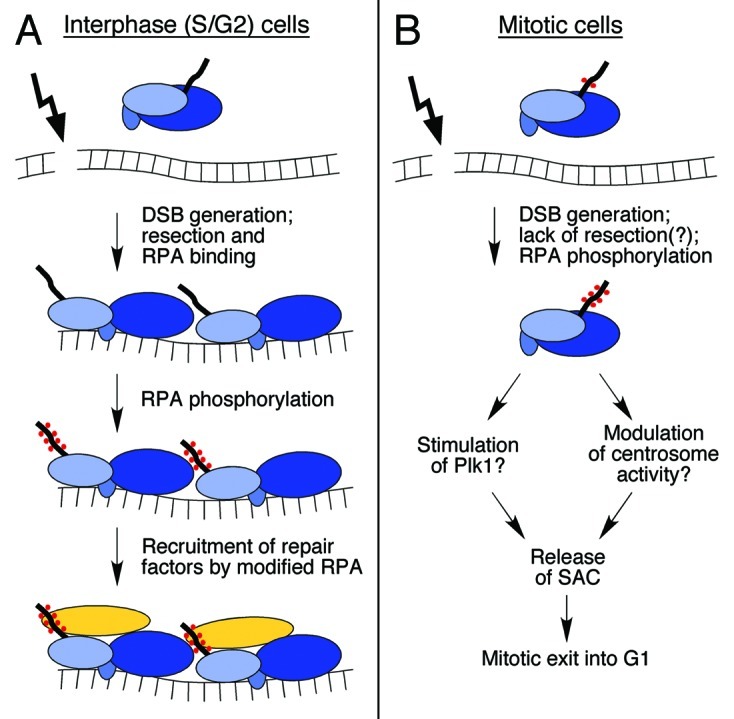

Study of human RPA has found that this factor is targeted for phosphorylation under genotoxic stress conditions. To provide a brief background, the N-terminus of the middle RPA2 subunit has nine sites that are subject to modification by members of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase–like kinase (PIKK; ATM, ATR and DNA-PK) and cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) families (Fig. 1A; reviewed in Binz et al.3). Phosphorylation of the RPA2 subunit proceeds through a favored pathway in interphase cells.4 Under DNA damage conditions that cause the generation of ssDNA, the resulting persistent RPA-ssDNA entities act to recruit and activate the ATR checkpoint kinase. Co-incident phosphorylation of Ser33 on RPA2 by ATR5 facilitates phosphorylation of adjacent N-terminal sites by cyclin-Cdk, and these events lead to further RPA2 phosphorylation by ATM, and likely DNA-PK (Fig. 1B). Phosphorylation has two major functional consequences. First, expression of an RPA2 subunit that mimics hyper-phosphorylation results in RPA having reduced loading onto DNA replication forks in vivo.5,6 These data have led to the suggestion that phosphorylation causes a shift of RPA activity to favor DNA repair at the expense of DNA replication. Second, RPA2 phosphorylation in interphase cells stimulates repair of chromosomal DNA damage caused either by camptothecin or bleomycin treatment.4 Because RPA phosphorylation does not significantly alter the high affinity of RPA for ssDNA,7,8 a likely scenario is that phosphorylated RPA located at DNA damage sites recruits factors for DNA repair (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1. Patterns of phosphorylation of human RPA2 in response to genotoxic stress. (A) Sites of phosphorylation on the N-terminus of the human RPA2 subunit are indicated by bold and underlined residues, with the sequence positions shown below. The identities of known and putative RPA2 kinases, reviewed in Anantha et al.,4 are indicated above the modified residues. (B) In interphase cells, formation of DSBs causes initial modification of S33 by ATR, stimulating phosphorylation of adjacent S23 and S29 by cyclin/Cdk2. These phosphorylation events stimulate subsequent modification of S4, S8, T21, and likely some or all residues in the S11/S12/S13 triplet. In mitotic cells, RPA2 is initially phosphorylated at S23 and S29 by cyclin B/Cdk2. Under conditions of mitotic DNA damage, the presence of pS23/pS29 facilitates additional modification of S4, S8, T21 and possibly S11/S12/S13. Because S33 (light gray box) was not seen to be phosphorylated under conditions of mitotic DNA damage,2 modification of S23/S29 (in dark gray box) is postulated to ‘prime’ RPA2 to undergo additional phosphorylation events under conditions of genotoxic stress.

Figure 2. Roles of RPA phosphorylation in interphase and mitotic cells. (A) Following generation of a DSB, cells in S and G2 can process the DSB ends by 5′ to 3′ resection, yielding ssDNA for subsequent involvement in homologous recombination. Heterotrimeric RPA binds to the ssDNA and undergoes a conformational change (see refs. in Binz et al.3), facilitating modification of the RPA2 N-terminus (thick line; phosphates are indicated with red dots). RPA2 modification is postulated to stimulate recruitment of DNA repair factors (yellow oval). (B) In mitotic cells, RPA2 normally becomes phosphorylated at the S23/S29 sites by cyclin B/Cdk1 which, under conditions of mitotic DNA damage, serves to stimulate additional phosphorylation events (see text and Figure 1B). The hyper-phosphorylated RPA is thought to act in a signaling capacity, possibly through stimulation of Plk1 activity or modulation of centrosome biology, to downregulate the SAC. This reduction in checkpoint activity allows cells to exit into a 2N G1 phase.

The finding that RPA2 is also subject to robust modification during a normal mitosis,8 suggested a role for RPA outside of interphase. Biochemical study of the mitotic RPA species found it to have decreased affinity for ATM, DNA-PK and DNA polymerase α as compared with non-phosphorylated RPA.8 Even so, test of non-stressed cells in which endogenous RPA2 was ‘replaced’ with a mutant preventing Cdk phosphorylation (and thus generation of the mitotic RPA form) found only minor effects on the cell cycle profile, as compared with cells replaced with a wt-RPA2 subunit.4

Testing crisis conditions (i.e., subjecting nocodazole-arrested cells to bleomycin) to unmask the significance of mitotic RPA phosphorylation revealed a novel activity for RPA. Previous studies of cultured mammalian cells observed that mitotic DNA damage causes a delay in anaphase onset,9 dependent on Brca1 and Chk1 function.10 Damage often causes mitotic catastrophe, generating multinucleate cells and eventual G1 arrest.11,12 Interestingly, RPA2 phosphorylation by cyclin B-Cdk1 was found to facilitate exit from a damaged mitosis into a 2N G1 phase.2 Cells replaced with a mutated RPA2 subunit lacking the two cyclin-Cdk sites had an increased fraction with chromatin staining of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) factor BubR1, and stained positive for cyclin B. These data indicate that the stimulation of mitotic exit by wild-type (i.e., phosphorylated) RPA is apparently mediated through the SAC. Damaged cells expressing the mutant subunit were also seen to undergo significantly higher levels of apoptotic cell death following release of the mitotic block, indicating phosphorylation increases cell viability under mitotic damage conditions.

As mentioned above, non-stressed cells expressing the mutant RPA2 subunit did not have any striking defects in mitotic transit.4 Thus, phosphorylation of the RPA2 Cdk sites is not essential for mitotic progression in the absence of DNA damage. Why then is the effect of RPA phosphorylation specific to cells experiencing genotoxic stress? Analysis of the pattern of mitotic RPA2 phosphorylation found that, similar to interphase cells,4 modification of the Cdk sites was needed to stimulate additional phosphorylation events at ~six adjacent sites on the RPA2 N-terminus when mitotic cells were treated to cause DNA damage. Interestingly, under damage conditions, the mitotic RPA2 was not seen to be modified at the Ser33 ATR site2 unlike interphase cells.4 These data suggest that mitotic phosphorylation of RPA2 by cyclin B-Cdk1 ‘primes’ RPA2 to become hyper-phosphorylated under mitotic DNA damage conditions. Perhaps because chromosomal condensation prevents efficient ATR activation (e.g., by inhibiting end-resection following -formation of a DSB), priming by cyclin B-Cdk1 would bypass a need for initial modification of RPA2 by the checkpoint kinase (Fig. 1B).

That RPA2 hyper-phosphorylation stimulates mitotic exit might at first glance be considered counter-intuitive. RPA2 hyper-phosphorylation is indicative of the presence of DNA damage. Thus, if acting to merely to signal damage, RPA2 phosphorylation might be expected to facilitate mitotic arrest rather than causing the observed stimulation of mitotic exit. Another possible explanation is that, because interphase RPA2 phosphorylation stimulates DNA repair, RPA modification could similarly promote DNA damage repair in mitotic cells, thereby reducing the DNA damage signal and consequently increasing mitotic exit. However, test of this idea found no compelling evidence that the RPA2 phosphorylation state affects the repair of mitotic DNA damage, although it likely facilitated repair following mitotic exit.2

Our favored hypothesis is that mitotic RPA2 phosphorylation acts in a signaling capacity to communicate to the SAC apparatus that RPA has been ‘activated’ for DNA repair. In the absence of the significant levels of phosphorylated RPA, mitotic exit would be delayed. Upon generation of this signal and mitotic exit, phosphorylated RPA would be immediately available to channel damaged DNA into the appropriate repair pathway(s). Some support for this model is provided by the observation that, while little chromatin-bound phosphorylated RPA was detected in bleomycin-treated and nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells, release of the mitotic block (i.e., removal of nocodazole) led to a robust increase in the amount of chromatin-bound hyper-phosphorylated RPA. This is in contrast to early G1 cells treated to cause DNA damage which showed minimal chromatin-bound RPA at similar times post-damage.2 A testable prediction of the model is that, in damaged mitotic cells with defective RPA modification, cells entering G1 would either experience a delay in repair or undergo repair with higher degrees of error.

Role of DNA Replication and Repair Proteins in the Mitotic DNA Damage Response

Clues as to the possible molecular bases by which RPA stimulates exit from a damaged mitosis are provided by past studies which demonstrated that mitotic DNA damage activates the SAC, causing a delay in anaphase onset. DNA damage-mediated activation of the SAC can occur through two apparently distinct routes involving Polo-like kinase-1 (Plk1) and the centrosome, although significant interplay likely exists between these pathways. Along with discussing each in turn, we will describe the potential input of particular DNA replication/repair proteins in modulating SAC activation through these known pathways.

Plk1

Plk1 (and its ortholog Cdc5 in budding yeast) is an essential serine/threonine kinase that regulates both mitotic entry and cytokinesis in eukaryotes (reviewed in Petronczki et al.13). Among its key substrates are the Cdc25C phosphatase, with phosphorylation stimulating Ccd25C action toward cyclin B1-Cdk1 and activating the kinase complex for mitotic entry; and the anaphase-promoting complex (APC), the latter event leading to APC activation and anaphase onset. Mitotic DNA damage in yeast leads to phosphorylation and inhibition of Cdc5 by the checkpoint kinase Rad53 (the homolog of vertebrate Chk2), causing a delay in mitotic exit.14,15 The general mechanism of inhibition is conserved in vertebrates with human Plk1 being targeted for inhibition in an ATM/ATR-dependent pathway involving the Chk2/Chk1 effector kinases.9,16-18 ATM-independent pathways likely also exist.19 The Plk1-mediated delay in mitotic exit is transient because a continuous low level rate of proteasomal destruction of cyclin B eventually causes cells to undergo mitotic slippage into a polyploid G1 phase.20

Regulation of Plk1 by replication and repair factors

BLM. BLM is a DNA helicase found to be defective in Bloom syndrome (BS), a genetic disorder that predisposes individuals to cancer development and progeria. Recently, Leng et al.21 found that BLM is a substrate of MPS1, a kinase in the SAC pathway that functions to prevent anaphase onset in the presence of unattached kinetochores.22 Following nocodazole treatment to activate the SAC, MPS1 catalyzes phosphorylation of human BLM on Ser144. This modification stimulates the physical association of BLM with Plk1, with this interaction apparently serving to maintain the cellular SAC. Nocodazole-treated BS cells ectopically expressing a BLM S144A mutant were unable to sustain a mitotic arrest, in contrast to cells expressing the wt BLM protein. Cells expressing the BLM S144A mutant also experienced higher levels of chromosomal missegregation, although normal rates of sister chromatid exchange. Because BS cells are defective in sister chromatid exchange, the effect of the phosphorylation site mutation on the SAC appears to be unrelated to the enzymatic activity of BLM. Overall, the data suggest that BLM is a positive effector in maintaining the SAC through inhibition of Plk1.

Association of Plk1 with DNA replication/DNA repair factors

It is possible that RPA acts through Plk1. Plk1 contains a C-terminal Polo-box domain (PBD) through which it first docks to previously phosphorylated substrates. The PBD recognizes a Ser-[pSer/pThr]-[Pro/X] motif, although the terminal Pro is found with a modest ≤ 2-fold higher frequency compared with most other residues.23 Note that because the [Ser/Thr]-Pro is the consensus phosphorylation site for cyclin B-Cdk1, the targets of Plk1 are often proteins previously modified by Cdk1. [The BLM Ser114 site is an exception because a PBD binding site (i.e., Ser-Ser-pSer-Pro) is generated upon phosphorylation by MPS1]. While the PBD is used for substrate recognition, a separate distinct motif is utilized for phosphorylation with the consensus being [Asp/Glu]-X-[Ser/Thr]-Φ.24 Proteomic screening of factors that support a mitosis-specific association with the Plk1 PBD detected, along with known Plk1 substrates, both the RPA1 and RPA2 subunits.25 While neither subunit has a consensus PBD-binding Ser-[pSer/pThr]-Pro, there is a potential Ser-pSer site on RPA2 (i.e., within the Ser11Ser12Ser13 element) that could mediate association with the PBD and thereby provide an avenue by which to modulate Plk1 activity. In this model, genotoxic stress would first provoke an ATM/ATR-dependent inhibition of Plk1, causing cells to remain in mitosis. Hyper-phosphorylation of RPA under these conditions would subsequently facilitate association with Plk1, relieving kinase inhibition and thereby stimulating mitotic exit (Fig. 2B). Analysis of a possible functional interplay between RPA and Plk1 to test this model is ongoing.

The proteomic screen mentioned above identified a number of other potential mitotic Plk1-binding factors in the DNA replication/DNA repair category that also warrant scrutiny. Both Tousled-like kinases Tlk1 and Tlk2,25 were detected, of interest because these ubiquitous kinases become activated during DNA replication in human cells and are rapidly inhibited in an ATM- and Chk1-dependent manner following DNA damage.26-28 Significantly, Tlk1 also promotes repair of DSBs and UV-induced damage, perhaps by stimulating histone removal at the site of DNA damage.29-33 That the Tlk1-Plk1 association is relevant is supported by the finding that Tlk1 is important for proper chromosome segregation during mitosis.30 Tlk may accomplish this role by regulating the activities of Aurora B kinase34,35 (essential for establishing bipolar attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle) and myosin II36 (a critical component of the contractile ring functioning during cytokinesis).

Prominent DNA replication factors were also identified25 as able to interact with the Plk1 PBD with mitotic specificity including: three of four subunits of the DNA polymerase α/DNA primase complex (which acts to prime Okazaki fragments during lagging strand synthesis); and multiple subunits of the hetero-hexameric MCM (mini-chromosome maintenance) complex, the latter complex serving as the replicative helicase for chromosomal DNA replication. Repair factors that were detected include: XRCC5 (also known as Ku80), a subunit of the heterotrimeric DNA-PK complex that is essential for DSB repair through non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ); MSH2 and MSH6, two DNA mismatch repair factors that are known to form heterodimers; and N-methylpurine-DNA glycosylase, acting in base excision repair. Although the results of such proteomic studies must be considered with a moderate degree of caution, past studies have demonstrated that the Xenopus laevis homolog of Plk1 (Plx1) is recruited to chromatin by MCM2 under DNA replication stress conditions, where it appears to reduce replication fork collapse under these conditions.37 Although the MCM complex could regulate Plk1 during a damaged mitosis, this possibility will need to be distinguished from the more pedestrian explanation that Plk1 modulates the activity of MCM in preparation for G1 entry and replication origin licensing. Similar caveats apply to the other factors mentioned above.

The centrosome

The centrosome is the cytoplasmic structure responsible for organizing the mitotic microtubule network, and regulates various cell cycle transitions including G1/S, G2/mitosis, and metaphase-anaphase (reviewed in Doxsey et al.38). During mitosis, changes in cyclin B and Cdk1 phosphorylation during prophase have been found to originate at the centrosome.39 More apropos, study of Drosophila syncytial embryos finds that cyclin B destruction at anaphase onset initiates at centrosomes and then spreads to the spindle equator.40 Reverse signaling also apparently occurs as use of centrosome fall off (cfo) mutant embryos suggests that the SAC signals to the centrosome to prevent the onset of cyclin B destruction, and thus anaphase.41

The effect of interphase DNA damage on centrosome biology has led to the suggestion that the centrosome integrates damage signals which, if of sufficient severity, cause centrosome inactivation and eventual mitotic catastrophe (see Loffler et al.42 and references therein). Examination of the molecular events involved has incriminated Chk2 as a factor necessary for centrosome inactivation following DNA damage caused by various genotoxic agents.43,44 Enhanced Chk1 centrosomal localization in response to DNA damage has also been postulated to decrease Cdk1 activation and hence prevent entry into mitosis.45

In addition to signaling factors, DNA replication and repair factors with potential centrosomal roles have been identified. Cells defective for members of the vertebrate RAD51 recombinase family (e.g., XRCC2, XRCC3, RAD51C/RAD51L2) or that express a dominant-negative RAD51 factor (SMRAD51) contain unrepaired damage and show mitotic centrosome fragmentation.46-48 The effect on centrosome number is apparently unrelated to ATM/ATR-dependent damage signaling.47 A direct involvement of RAD51 and paralogues with the centrosome is not yet established but is suggested by the finding that RAD51 can physically interact with γ-tubulin, a centrosome-associated factor.49 As a second example, while the recombination mediator BRCA2 is predominantly a nuclear factor, a fraction of the BRCA2 pool localizes to centrosomes in the S and early M phases. A reduction in the level of cytoplasmic and hence centrosomal BRCA2 causes centrosome amplification and binucleation of cells.50,51

Does the observed role of RPA in modulating mitotic transit occur through the centrosome? Proteomic investigation of human centrosomal components identified two of the three RPA subunits in centrosomal preparations from human cells.52 Preliminary use of phospho-specific RPA2 antibodies has also indicated the presence of phosphorylated RPA in centrosomes, by virtue of co-localization with γ-tubulin (Anantha RW, Borowiec JA, unpublished observations). The centrosome is thus a second avenue by which phosphorylated RPA, and other replication/repair factors, could possibly affect the SAC. Demonstrating these activities will require additional evidence such as DNA damage-dependent association of implicated DNA replication/repair factors with centrosomal components.

Concluding Remarks

The studies mentioned in this review provide an intriguing glimmer of potential new roles for DNA replication and repair factors in regulation of the SAC through Plk1 and/or the centrosome under genotoxic stress conditions. While yet primarily a glint, there appear to be sufficient clues in the field of mitotic regulation to support a more focused study of possible mechanistic roles of DNA metabolic factors on the SAC. These efforts should reveal whether RPA alters transit through a damaged mitosis by one of the two postulated mechanisms discussed above, or if a novel pathway is used. Such studies will also determine if mitotic crises expose additional roles for DNA replication and repair factors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Susan Smith for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in the Borowiec laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM083185, an Exceptional Project Award Grant from the Breast Cancer Alliance, the New York University Cancer Institute, the Rita J. and Stanley Kaplan Comprehensive Cancer Center and National Cancer Institute Grant P30CA16087.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/7496

References

- 1.Reed JC. Dysregulation of apoptosis in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2941–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anantha RW, Sokolova E, Borowiec JA. RPA phosphorylation facilitates mitotic exit in response to mitotic DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12903–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binz SK, Sheehan AM, Wold MS. Replication protein A phosphorylation and the cellular response to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1015–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anantha RW, Vassin VM, Borowiec JA. Sequential and synergistic modification of human RPA stimulates chromosomal DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35910–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson E, Nievera CJ, Klimovich V, Fanning E, Wu X. RPA2 is a direct downstream target for ATR to regulate the S-phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39517–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassin VM, Wold MS, Borowiec JA. Replication protein A (RPA) phosphorylation prevents RPA association with replication centers. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1930–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1930-1943.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binz SK, Lao Y, Lowry DF, Wold MS. The phosphorylation domain of the 32-kDa subunit of replication protein A (RPA) modulates RPA-DNA interactions. Evidence for an intersubunit interaction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35584–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakley GG, Patrick SM, Yao J, Carty MP, Turchi JJ, Dixon K. RPA phosphorylation in mitosis alters DNA binding and protein-protein interactions. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3255–64. doi: 10.1021/bi026377u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits VA, Klompmaker R, Arnaud L, Rijksen G, Nigg EA, Medema RH. Polo-like kinase-1 is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:672–6. doi: 10.1038/35023629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Tran T, Zhang L, Hatcher R, Zhang P. DNA damage-induced mitotic catastrophe is mediated by the Chk1-dependent mitotic exit DNA damage checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409130102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreassen PR, Lacroix FB, Lohez OD, Margolis RL. Neither p21WAF1 nor 14-3-3sigma prevents G2 progression to mitotic catastrophe in human colon carcinoma cells after DNA damage, but p21WAF1 induces stable G1 arrest in resulting tetraploid cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7660–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petronczki M, Lénárt P, Peters JM. Polo on the rise-from mitotic entry to cytokinesis with Plk1. Dev Cell. 2008;14:646–59. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng L, Hunke L, Hardy CF. Cell cycle regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae polo-like kinase cdc5p. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7360–70. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, et al. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1166–71. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Vugt MA, Smits VA, Klompmaker R, Medema RH. Inhibition of Polo-like kinase-1 by DNA damage occurs in an ATM- or ATR-dependent fashion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41656–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang J, Erikson RL, Liu X. Checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) is required for mitotic progression through negative regulation of polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11964–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604987103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsvetkov LM, Tsekova RT, Xu X, Stern DF. The Plk1 Polo box domain mediates a cell cycle and DNA damage regulated interaction with Chk2. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:609–17. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.4.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan JH, Feng Y, Fisher RH, Maloid S, Longo DL, Ferris DK. Polo-like kinase 1 inactivation following mitotic DNA damaging treatments is independent of ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:417–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brito DA, Rieder CL. Mitotic checkpoint slippage in humans occurs via cyclin B destruction in the presence of an active checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leng M, Chan DW, Luo H, Zhu C, Qin J, Wang Y. MPS1-dependent mitotic BLM phosphorylation is important for chromosome stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11485–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601828103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisk HA, Mattison CP, Winey M. A field guide to the Mps1 family of protein kinases. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:439–42. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.4.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elia AE, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Proteomic screen finds pSer/pThr-binding domain localizing Plk1 to mitotic substrates. Science. 2003;299:1228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1079079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima H, Toyoshima-Morimoto F, Taniguchi E, Nishida E. Identification of a consensus motif for Plk (Polo-like kinase) phosphorylation reveals Myt1 as a Plk1 substrate. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25277–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowery DM, Clauser KR, Hjerrild M, Lim D, Alexander J, Kishi K, et al. Proteomic screen defines the Polo-box domain interactome and identifies Rock2 as a Plk1 substrate. EMBO J. 2007;26:2262–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silljé HH, Takahashi K, Tanaka K, Van Houwe G, Nigg EA. Mammalian homologues of the plant Tousled gene code for cell-cycle-regulated kinases with maximal activities linked to ongoing DNA replication. EMBO J. 1999;18:5691–702. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groth A, Lukas J, Nigg EA, Silljé HH, Wernstedt C, Bartek J, et al. Human Tousled like kinases are targeted by an ATM- and Chk1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. EMBO J. 2003;22:1676–87. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause DR, Jonnalagadda JC, Gatei MH, Sillje HH, Zhou BB, Nigg EA, et al. Suppression of Tousled-like kinase activity after DNA damage or replication block requires ATM, NBS1 and Chk1. Oncogene. 2003;22:5927–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silljé HH, Nigg EA. Identification of human Asf1 chromatin assembly factors as substrates of Tousled-like kinases. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1068–73. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrera P, Moshkin YM, Gronke S, Sillje HH, Nigg EA, Jackle H, et al. Tousled-like kinase functions with the chromatin assembly pathway regulating nuclear divisions. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2578–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.276703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunavala-Dossabhoy G, Balakrishnan SK, Sen S, Nuthalapaty S, De Benedetti A. The radioresistance kinase TLK1B protects the cells by promoting repair of double strand breaks. BMC Mol Biol. 2005;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen SP, De Benedetti A. TLK1B promotes repair of UV-damaged DNA through chromatin remodeling by Asf1. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunavala-Dossabhoy G, De Benedetti A. Tousled homolog, TLK1, binds and phosphorylates Rad9; TLK1 acts as a molecular chaperone in DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Z, Riefler GM, Saam JR, Mango SE, Schumacher JM. The C. elegans Tousled-like kinase contributes to chromosome segregation as a substrate and regulator of the Aurora B kinase. Curr Biol. 2005;15:894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Z, Gourguechon S, Wang CC. Tousled-like kinase in a microbial eukaryote regulates spindle assembly and S-phase progression by interacting with Aurora kinase and chromatin assembly factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3883–94. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto M, Matsui T, Iwabuchi K, Date T. PKU-beta/TLK1 regulates myosin II activities, and is required for accurate equaled chromosome segregation. Mutat Res. 2008;657:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trenz K, Errico A, Costanzo V. Plx1 is required for chromosomal DNA replication under stressful conditions. EMBO J. 2008;27:876–85. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doxsey S, Zimmerman W, Mikule K. Centrosome control of the cell cycle. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackman M, Lindon C, Nigg EA, Pines J. Active cyclin B1-Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:143–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang J, Raff JW. The disappearance of cyclin B at the end of mitosis is regulated spatially in Drosophila cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:2184–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakefield JG, Huang JY, Raff JW. Centrosomes have a role in regulating the destruction of cyclin B in early Drosophila embryos. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1367–70. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Löffler H, Lukas J, Bartek J, Krämer A. Structure meets function--centrosomes, genome maintenance and the DNA damage response. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2633–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takada S, Kelkar A, Theurkauf WE. Drosophila checkpoint kinase 2 couples centrosome function and spindle assembly to genomic integrity. Cell. 2003;113:87–99. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsvetkov L, Xu X, Li J, Stern DF. Polo-like kinase 1 and Chk2 interact and co-localize to centrosomes and the midbody. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8468–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Löffler H, Bochtler T, Fritz B, Tews B, Ho AD, Lukas J, et al. DNA damage-induced accumulation of centrosomal Chk1 contributes to its checkpoint function. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2541–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffin CS, Simpson PJ, Wilson CR, Thacker J. Mammalian recombination-repair genes XRCC2 and XRCC3 promote correct chromosome segregation. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:757–61. doi: 10.1038/35036399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daboussi F, Thacker J, Lopez BS. Genetic interactions between RAD51 and its paralogues for centrosome fragmentation and ploidy control, independently of the sensitivity to genotoxic stresses. Oncogene. 2005;24:3691–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindh AR, Rafii S, Schultz N, Cox A, Helleday T. Mitotic defects in XRCC3 variants T241M and D213N and their relation to cancer susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1217–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lesca C, Germanier M, Raynaud-Messina B, Pichereaux C, Etievant C, Emond S, et al. DNA damage induce gamma-tubulin-RAD51 nuclear complexes in mammalian cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:5165–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tutt A, Gabriel A, Bertwistle D, Connor F, Paterson H, Peacock J, et al. Absence of Brca2 causes genome instability by chromosome breakage and loss associated with centrosome amplification. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1107–10. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han X, Saito H, Miki Y, Nakanishi AA. A CRM1-mediated nuclear export signal governs cytoplasmic localization of BRCA2 and is essential for centrosomal localization of BRCA2. Oncogene. 2008;27:2969–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen JS, Wilkinson CJ, Mayor T, Mortensen P, Nigg EA, Mann M. Proteomic characterization of the human centrosome by protein correlation profiling. Nature. 2003;426:570–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]