Abstract

Objective

To report two cases of concomitant choroidal melanoma and intraocular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in two patients.

Design

Case report.

Participants

Two patients with yellow creamy infiltrates in fundo.

Intervention

Both patients had a complete ophthalmologic evaluation and histology was obtained after enucleation of the affected eye.

Main Outcome Measures

Histology findings of the enucleated eyes.

Results

One patient showed a choroidal melanoma with a primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma located solely in the affected eye. The other patient showed a systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma with ocular manifestations concomitant with a choroidal melanoma.

Conclusions

In the presence of yellow creamy infiltrates one should include a choroidal lymphoma in the differential diagnosis even if there is another clear pathologic condition. Furthermore in those cases systemic disease should be excluded.

Key Words: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Uveal melanoma, Choroidal melanoma

Introduction

Uveal melanoma is the most common intraocular malignant tumour in adults with an annual incidence of approximately 5–6 per million in the Western world [3]. Intraocular non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a rare and, in most cases, a B-cell lymphoma involving the retina, vitreous, uvea or optic nerve and can be primary or secondary. Primary NHL can occur independently or in conjunction with central nervous system lymphoma. Secondary intraocular lymphomas are mostly located in the uvea [1, 2].

In this report we describe two cases with a choroidal melanoma and a concomitant intraocular NHL of the same eye. Apart from the typical appearance of the choroidal melanoma, both patients showed creamy yellow choroidal spots on fundus examination. Both cases showed a low-grade B-cell NHL on histology. Full hematologic screening revealed systemic disease in the second patient.

Case Report

Case 1

A 63-year-old man was referred by his ophthalmologist for a pigmented intraocular tumour in his right eye in December 2006. This lesion was diagnosed during his yearly ophthalmic examination for his insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus since 2002. On examination the patient had full vision in both eyes with no proptosis and normal movements of the eyes. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment showed no abnormalities. Dilated fundus examination was uneventful in the left eye and the right showed a juxtapapillary pigmented lesion touching the optic disk over more than 180 degrees. The lesion was slightly elevated and showed orange pigment, no drusen and no subretinal fluid. The posterior pole showed in adjunction of the pigmented lesion a wide field of yellow spotted lesions, which were not elevated (fig. 1a). The vitreous was clear. No diabetic retinopathy was seen. On B-scan ultrasound examination the choroidal lesion measured 4.7 × 4.5 mm in diameter and 2.3 mm in thickness (including the sclera). Choroidal excavation was visible combined with high internal reflection of 45%. Temporal of the optic disk no prominence was shown. Although the lesion was suspected for a choroidal melanoma it was decided to observe it. In the following year the pigmented lesion slowly progressed and an enucleation of the right eye was performed because the tumour encompassed the optic nerve for almost 360 degrees. Alternative treatment modalities such as proton beam radiation and ruthenium plaque brachytherapy were also offered to the patient but he chose enucleation.

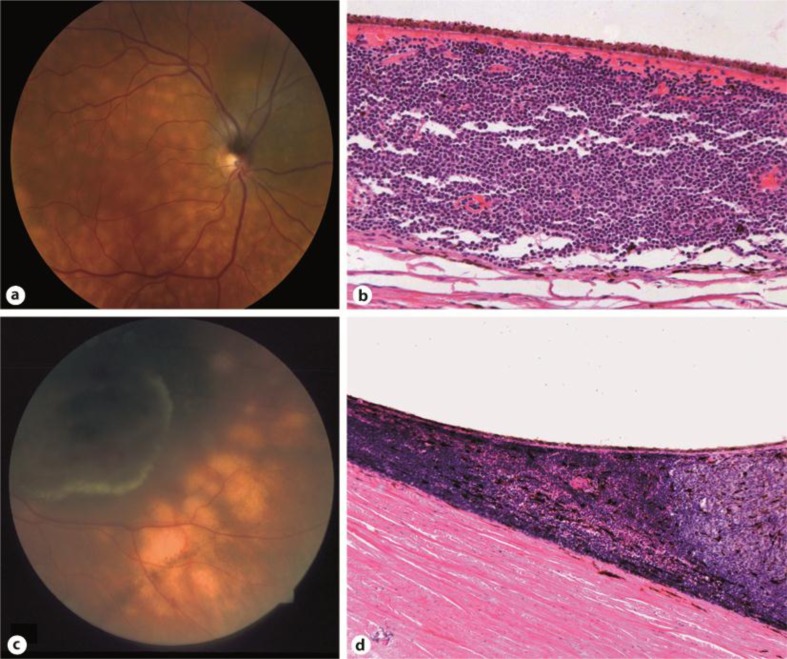

Fig. 1.

a Fundus of patient 1 showing a juxtapapillary choroidal melanoma surrounded by creamy yellow choroidal spots. b Patient 1. Dense lymphocytic choroidal infiltrates outside the melanoma area. The lymphocytes are diffusely, but tightly packed unlike inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate and show irregular nuclei and nuclear membranes. Paraffin section. Original magnification: 200×. c Characteristic yellow spotted fundus of patient 2 with choroidal melanoma in inferior temporal area. d Patient 2. Dense lymphocytic infiltrate at the margins of the melanoma extending towards the equator. Celloidin section. Original magnification: 100×.

Histopathology of the enucleated eye revealed epitheloid melanoma of the choroid with a diameter of 5 mm and thickness of 1 mm (pT1a) [8]. The posterior pole demonstrated numerous uveal infiltrates extending towards the equator. These lesions were immunohistochemically identified as an extranodal MALT lymphoma. More infiltrates were found scattered in the choroid, in the ciliary body and surrounding one vorticose vein (fig. 1b). Immunohistochemical staining of the lymphocytic cells showed negativity of CD5, CD23 and Cycl1D1, making the diagnosis of B-cell chronic lymphatic leukemia or mantle cell lymphoma less likely. Analysis of clonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin gene showed a peak of 314 bp in the FR1 region. No peak was observed in other regions. Systemic screening for possible metastases of the melanoma or systemic lymphoma by the oncologist was negative. This examination included the contralateral eye, saliva glands, lungs and stomach. No further treatment was given and after 3 years of follow-up there were no signs for distant metastasis for his uveal melanoma nor were there any signs for systemic lymphoma.

Case 2

A 33-year-old woman with systemic lymphoma had visual complaints of her left eye and was referred by her haematologist in November 1984. The systemic lymphoma originated retroperitoneally and was histologically confirmed as extramarginal zone lymphoma. In the last eight years she received multiple chemotherapy regimens and total body radiation. On examination, visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 5/20 in the left eye. There was no exophthalmos and eye movement was full. Both eyes had a normal anterior segment on slit-lamp examination. Dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed a normal fundus. The left eye showed a small greyish tumour in the inferior temporal quadrant and was suspected of NHL (fig. 1c). The patient was treated with systemic chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide and vincristine) and the eye received 30 Gy radiation (8 MV photons) in fifteen fractions of 2 Gy. There was, however, no clinical regression of the tumour and diagnosis was changed to choroidal melanoma based on the fluorescence angiography and ultrasound of 1.8 mm on the A-scan. It was decided to observe the lesion. Three years later yellow spotted lesions appeared in the posterior pole around the tumour. These lesions were not visible on fluorescence angiography. Another two years later, the pigmented lesion slowly progressed with rupturing of Bruch's membrane. The tumour thickness was 4 mm on ultrasound and haemorrhage and oedema were seen over the tumour. Therefore the left eye was enucleated. The patient died two years later due to systemic lymphoma.

Histopathology of the enucleated eye revealed a spindle cell melanoma of the choroid with a diameter of 9 mm and thickness of 3 mm (pT1b) growing through Bruch's membrane and invading the retina. At the margins of the tumour dense lymphocytic infiltrates were found which were more extensive than usual around melanomas (fig. 1d) [9]. These lymphoid infiltrates were immunohistochemically identified as NHL. These infiltrates were also found episclerally and around posterior emissary blood vessels. There was a shortage of paraffin-embedded material to further analyze the NHL. Immunohistochemistry for NHL on celloidin sections was and is not available.

Comment/Discussion

Literature has shown that many patients with uveal melanoma have or later develop a second or even a third type of malignancy. This secondary or third malignancy differs from patient to patient. Recent reports cite a frequency of around 10 percent for a double and 1 percent for a triple malignancy. Other literature showed that, irrespective of tumour size, patients had a 1 to 2 percent chance of having a concurrent diagnosis of uveal melanoma and a second malignancy, if screened with PET-CT [10, 11, 12].

The two reported cases illustrate an extremely rare combination of choroidal melanoma with an intraocular lymphoma. In both cases the typical creamy yellow choroidal infiltrates of intraocular lymphoma are seen by fundoscopy as described by Jakobiec et al. in 1987 [4]. When two rare conditions both occur in the same eye of a patient the chance is high that only one of the two conditions is diagnosed correctly. In the first patient the intraocular lymphoma was not diagnosed until after histology of the enucleated eye. On the other hand the choroidal melanoma was not diagnosed in the second case until after failure of the irradiation to control the intraocular tumour diagnosed as a choroidal manifestation of the existing systemic lymphoma.

A literature search on patients with a choroidal melanoma and simultaneous primary or secondary intraocular lymphoma delivered us only one case report describing a patient with choroidal (necrotic) melanoma concomitant with asymptomatic systemic B-cell lymphoma [6]. In this report the NHL was clinically undetected and the diagnosis of NHL was obtained by histopathologic examination of the enucleated eye. This case is comparable with our first case.

The diagnosis intraocular NHL is often delayed because the choroidal infiltrates are often asymptomatic and not recognised by the ophthalmologist. Intraocular lymphoma can be located in the retina and the uveal tract and can be a primary lesion or a secondary lesion in systemic lymphoma disease. The retinal lymphomas are often aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and in a high percentage of the cases there is central nervous system involvement. The primary choroidal lymphomas are often low-grade lymphomas and are diagnosed as extranodal marginal zone lymphomas, while the type of secondary choroidal lymphomas depends on the type of systemic lymphomas. In most instances these are low-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. In both our cases a low-grade extranodal marginal zone lymphoma was diagnosed. In the first patient with the primary choroidal lymphoma no signs for systemic disease occurred within a follow-up time of 2 years. In the second case the patient received multiple treatments for systemic NHL eight years before the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma. It took another 7 years before she died of her systemic lymphoma.

Although a relationship between malignant melanoma and NHL is hypothesized, such as shared genetic or etiologic factors [5, 7], no strong evidence can be found. This leaves us probably with a description of two extremely rare cases with both choroidal melanoma and choroidal lymphoma.

Conclusion

In the presence of yellow creamy choroidal infiltrates one should include a choroidal lymphoma in the differential diagnosis even if there is another clear pathologic condition. Furthermore in those cases systemic disease should be excluded.

References

- 1.Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36:564–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimm SA, McCannel CA, Omuro AM, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma with intraocular involvement: International PCNSL Collaborative Group Report. Neurology. 2008;71:1355–1360. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327672.04729.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh AD, Kivelä T. The collaborative ocular melanoma study. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005;18:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakobiec FA, Sacks E, Kronish JW, et al. Multifocal static creamy choroidal infiltrates. An early sign of lymphoid neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:397–406. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna DB, Doherty VR, McLaren KM, Hunter JAA. Malignant melanoma and lymphoproliferative malignancy: is there a shared aetiology? Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:171–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Küchle M, Tiemann M, Holbach L, Naumann GOH. Necrotic malignant melanoma of the choroid and concurrent intraocular manifestation of malignant non-Hodgkin's B cell lymphoma. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000310455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekström Smedby K, Hjalgrim H, Melbye M, et al. Ultraviolet radiation exposure and risk of malignant lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:199–209. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermanek P, Sobin LH, International Union Against Cancer (UICC) 4th. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1987. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. Revised 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobin LH, Wittekind CH. 6th. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. International Union Against Cancer (UICC): TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diner-West M, et al. Second primary cancers after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:601–604. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callego SA, Al-Khalifa S, Ozdal PC, Edelstein C, Burnier MN., Jr The risk of other primary cancer in patients with uveal melanoma: a retrospective cohort study of a Canadian population. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freton A, Chin KJ, Raut R, Tena LB, Kivelä T, Finger PT. Initial PET/CT staging for choroidal melanoma: AJCC correlation and second nonocular primaries in 333 patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;22:236–243. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]