Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death in United States and throughout Europe. While a higher risk of HF with antecedent myocardial infarction (MI) has been reported in offspring whose parents had MI before age 55, it is unclear whether adherence to healthful behaviors could mitigate that risk. The aim of the current study was therefore to prospectively examine if adherence to healthy weight, regular exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and abstinence from smoking can attenuate such increased HF risk. The information on parental history of MI and lifestyle factors was collected using questionnaires. Subjects adhering to at least three healthy lifestyle factors were classified as having good vs. poor lifestyle score. Incident HF was assessed via yearly follow-up questionnaires and validated in a subsample. During an average follow up of 21.7 (6.5) years, 1,323 new HF cases (6.6%) of which 190 (14.4%) were preceded by MI occurred. Compared to subjects with good lifestyle score and no parental history of premature MI, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for incident HF with antecedent MI was 3.21 (1.74–5.91) for people with good lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI; 1.52 (1.12–2.07) for individuals with poor lifestyle score and no parental history of premature MI; and 4.60 (2.55–8.30) for people with poor lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI. In conclusion, our data suggest that even in people at higher risk of HF due to genetic predisposition, adherence to healthful lifestyle factors may attenuate such an elevated HF risk.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Heart Failure, Myocardial Infarction, Lifestyle factors, Risk factors

The current study was designed to examine the extent to which adherence to healthy lifestyle factors might attenuate the increased risk of heart failure (HF) with antecedent myocardial infarction (MI) in individuals with parental history of premature MI.

METHODS

The Physicians’ Health Study (PHS) I is a completed randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, designed to study the effects of low-dose aspirin (ASA) and beta-carotene on cardiovascular disease and cancer among US male physicians. In 1997, a second randomized trial PHS II was started and included 7,641 physicians from original PHS I along with 7,000 new physicians. A detailed description of the PHS I and II has been published elsewhere 1,2. Participants from PHS I including the 7,641 subjects who participate in PHS II are subsequently referred to as PHS. Of the 22,071 original subjects in the PHS, we excluded subjects with missing information on 12-month questionnaire (n=60), those with missing data on parental history of MI for both parents or missing parental age of MI (n=1,416), those with prevalent HF (n=25) at 12 months post-randomization, and those with missing information on covariates (n=510). Thus, a final sample of 20,060 participants was selected for current analyses. Each participant gave written informed consent and the Institutional Review Board at Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved the study protocol.

During the 12 month follow-up questionnaire, information on parental history of myocardial infarction was collected using the following questions: Has your mother ever had a documented myocardial infarction? If yes, at what age? Has your father ever had a documented myocardial infarction? If yes, at what age?” Possible answers for the initial question were “No”, “Yes”, and “Don’t know”. In cases where both parent had a history of MI, we used the minimum age at diagnosis of parental MI for analyses. A parental history of premature MI was defined as having MI before 55 years of age.

Cardiovascular endpoints including HF in the PHS have been ascertained using annual follow-up questionnaires. A questionnaire was mailed to each participant every 6 months during the first year and has been mailed annually thereafter to obtain information on compliance with the intervention and the occurrence of new medical diagnoses, including HF. The validation of HF in the PHS has been previously reported 3.

Self-reported baseline weight and height were used to compute body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by height in meter squared). Each lifestyle factor was dichotomized as follows: non-current smoker vs. current smoker; normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2) vs. overweight/obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2); weekly alcohol use vs. more/less frequent alcohol use; and regular exercise (weekly) vs. infrequent/no exercise (< weekly). These cut points were chosen based on prior associations between individual lifestyle factors and HF risk in this cohort or public health recommendations 4. Each participant received 1 point for each of the following: BMI <25, non-current smoking, weekly alcohol use, and ≥ weekly exercise. Thus, study participants were categorized according to the number of desirable lifestyle factors (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4). A score ‘>2’ was defined as a ‘good lifestyle score’ while a score of ‘≤2’ was defined as a ‘poor lifestyle score.’

Demographic data were collected at baseline (1982–1984). Age was used as a continuous variable. Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) was made on self-reports via questionnaires mailed to each participant every 6 months during the first year and annually thereafter. Diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CHD) was initially made on self-reports via follow-up questionnaires. An Endpoint Committee reviewed medical records to confirm the diagnosis of CHD. Hypertension (HTN) was defined as anyone who self reported the diagnosis, BP >140/90 mm Hg per JNC7 guidelines or on the basis of medication list provided by the study participants. All types of atrial fibrillation (AF) cases were assessed via follow-up questionnaires. These self- reports of AF have been validated in the same cohort using a more detailed questionnaire on the diagnosis of AF and the review of medical records in a prior study 5.

Compared to subjects with good lifestyle score and no parental history of premature MI as reference, we classified the remaining participants into those with good lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI, poor lifestyle score and no history of parental premature MI, and poor lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI. We computed person-time of follow up from 12-month post-randomization until the first occurrence of a) HF, b) death, or c) date of receipt of last follow-up questionnaire. We used Cox proportional hazard models to compute multivariable adjusted hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals using subjects with good lifestyle score and no parental history of premature MI as the reference group. We assessed confounding by established risk factors for HF. The initial model adjusted only for age. A second model additionally controlled for DM, HTN, AF and ASA randomization status.

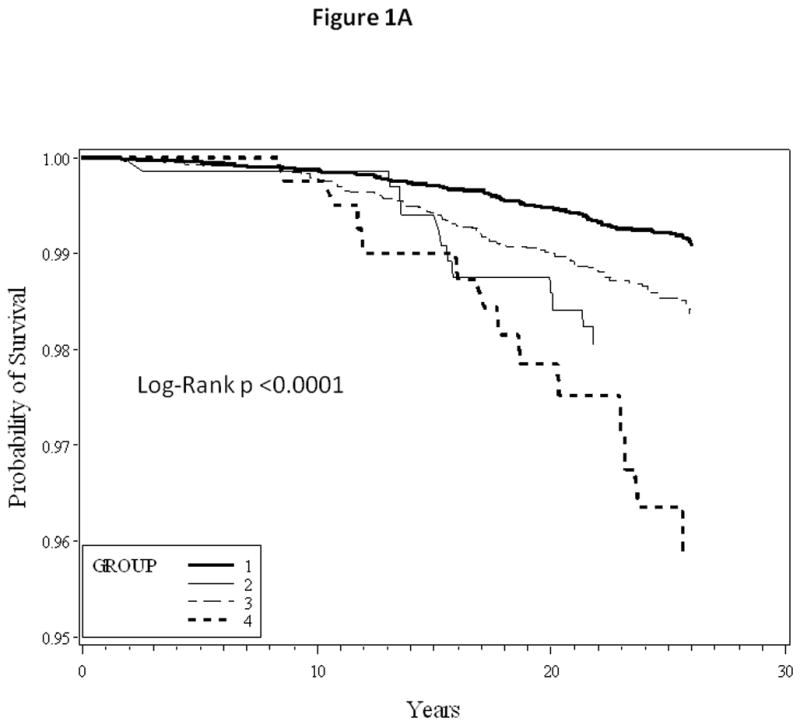

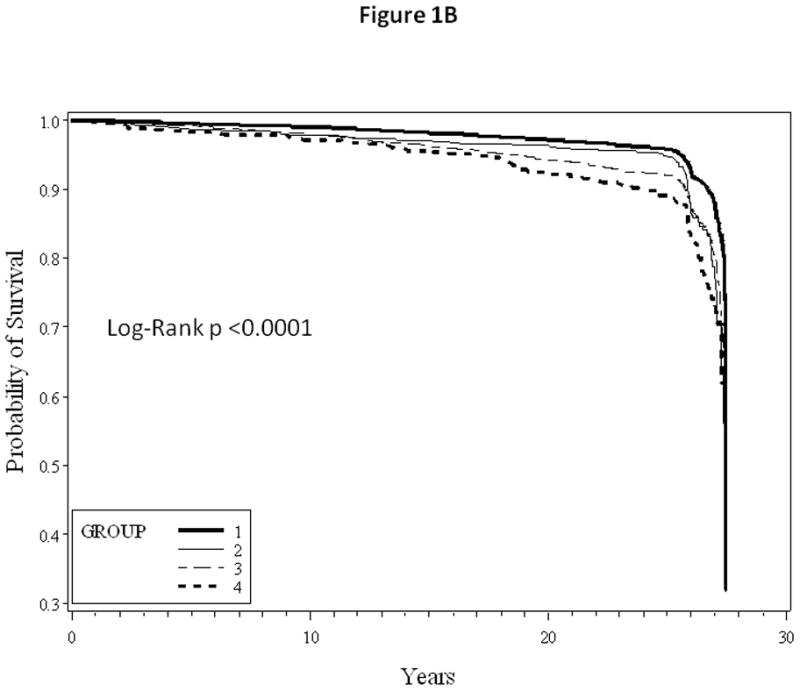

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were also used to compare the HF free and MI free survival for each of the four groups considered in our analysis. Additionally, we conducted a secondary analysis stratified by each decade of age at entry to assess effect modification by age. Assumptions for proportional hazard models were tested using product terms of log (time) factor and variables of interest and were met (all p values > 0.05). All analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, NC). Significance level was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 20,060 participants in the PHS I, the mean age at 12 months post randomization was 55 (±9.5) years. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the study participants. While 94% of the subjects did not report parental history of premature MI, 6% of the participants had at least one parent who had a MI before the age of 55 y. In addition, 60% of the subjects had a good lifestyle score. Individuals with parental history of premature MI were noted to be younger than those with no parental history of premature MI. As expected, the prevalence of DM and HTN was also noted to be higher among individuals with poor lifestyle score than those with good lifestyle score.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 20,060 participants of the Physicians’ Health Study

| Parameter | No parental history of premature MI

|

Parental history of premature MI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | |

| n=11,336 | n=7,581 | n=697 | n=446 | |

| Age (years) | 54 ± 9.5 | 56 ± 9.4 | 51 ± 7.8 | 53 ± 8.0 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24 ± 2.3 | 26 ± 2.9 | 24 ± 2.3 | 26 ± 2.9 |

| Randomized to Aspirin | 50% | 50% | 51% | 46% |

| Current Exercise | 91% | 45% | 90% | 47% |

| Never smoker | 55% | 42% | 55% | 40% |

| Past smoking | 43% | 35% | 42% | 32% |

| Current smoker | 2.9% | 23% | 2.7% | 28% |

| Moderate drinking (weekly) | 68% | 21% | 69% | 25% |

| Hypertension | 20% | 29% | 19% | 27% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.2% | 4.7% | 2.7% | 4.0% |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1.8% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 1.6% |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 8.4% | 13% | 14% | 19% |

Abbreviation: MI – Myocardial Infarction

During an average follow up of 22 years, 1,323 new cases of HF (6.6%) were documented in this cohort. Of these, 190 cases (14%) occurred in individuals with antecedent MI. Compared to subjects with good lifestyle score and no parental history of premature MI, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for incident HF with antecedent MI was 3.21 (1.74–5.91) for people with good lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI, 1.52 (1.12–2.07) for individuals with poor lifestyle score and no history of parental premature MI, and 4.60 (2.55–8.30) for people with poor lifestyle score and parental history of premature MI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rates and relative risks (95% CI) of heart failure according to the parental history of myocardial infarction (age <55 y) and lifestyle score

| Parameter | No parental history of premature MI

|

Parental history of premature MI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | |

| Cases/person-years | 79/253925 | 86/156559 | 12/16304 | 13/9449 |

| Crude incidence rate (10,000 person-years) | 3.1 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 13.8 |

| Unadjusted Model | 1.0 | 1.83 (1.35–2.49) | 2.31 (1.26–4.25) | 4.52 (2.51–8.12) |

| Age-adjusted Model | 1.0 | 1.68 (1.23–2.28) | 3.25 (1.76–5.98) | 5.21 (2.90–9.38) |

| Multivariable Model | 1.0 | 1.52 (1.12–2.07) | 3.21 (1.74–5.91) | 4.60 (2.55–8.30) |

Multivariable Model: age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and aspirin randomization

Abbreviation: MI – Myocardial Infarction

When stratified by age, the influence of healthful lifestyle factors appeared to be stronger with younger age at entry (Table 3). Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing HF and MI free survival between different groups are as shown in Figure 1A and 1B, respectively.

Table 3.

Relative risks (95% CI) of heart failure according to the parental history of myocardial infarction (age <55 y) and lifestyle score stratified by age

| Age Group (years) | No of Cases | Sample Size | No parental history of premature MI

|

Parental history of premature MI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | Good lifestyle score | Poor lifestyle score | |||

| 40–50 | 27 | 7,571 | 1.0 | 1.46 (0.62–3.47) | 3.18 (0.88–11.57) | 6.93 (1.92–24.98) |

| 50–60 | 69 | 6,891 | 1.0 | 2.97 (1.76–5.01) | 0.81 (0.11–6.00) | 3.08 (0.91–10.40) |

| 60–70 | 61 | 4,101 | 1.0 | 1.07 (0.60–1.90) | 8.05 (3.50–18.53) | 8.00 (3.29–19.44) |

| 70–80 | 31 | 1,335 | 1.0 | 0.70 (0.32–1.52) | 2.68 (0.35–20.74) | 1.87 (0.25–14.23) |

| 80+ | 2 | 162 | 1.0 | ** | ** | ** |

Not enough events for stable estimates of effect

Abbreviation: MI – Myocardial Infarction

Figure 1.

1A: Kaplan-Meier heart failure free survival curves

1B: Kaplan-Meier myocardial infarction free survival curves

Group 1: No parental history of premature myocardial infarction and good lifestyle score

Group 2: Parental history of premature myocardial infarction and good lifestyle score

Group 3: No parental history of premature myocardial infarction and poor lifestyle score

Group 4: Parental history of premature myocardial infarction and poor lifestyle score

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that in the presence of parental history of premature MI, adherence to healthful lifestyle factors was associated with a lower risk of HF with antecedent MI. Our data suggest that the influence of healthful lifestyle factors on above association might be stronger in younger compared to older ages.

Genetic factors have been demonstrated to play an important role in the development of HF 6,7. Several important HF predictors have also been shown to have a strong genetic component including HTN 8, DM 9, CHD 10, AF 11, left ventricular mass (LVM) 12, and obesity 13. Genomewide association studies have demonstrated genetic loci associated with HF risk 14. However it remains critically important to identify simple and practical means to identify people with a high genetic susceptibility to HF risk and design simple, yet cost-effective strategies to mitigate such a risk.

In a prior study on the same cohort, Djoussé et al 15 demonstrated a 32% higher risk of HF in the offspring of subjects with a parental history of premature MI (i.e. before age 55) in comparison to those with no parental history of premature MI. Data from the Framingham Study also demonstrated genetic susceptibility to HF onset in the offspring with ~18% of the risk attributable to parental history of HF 16.

Data from this cohort 4 has also shown beneficial effects of good lifestyle factors on the incidence of HF. Regular exercise, not smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, maintaining a normal weight, consumption of fruit and vegetables, and breakfast cereal were both individually and jointly associated with a lower lifetime risk of HF. The observed lifetime risk of HF varied from 21.20% (95% CI: 16.80%–25.60%) among those who did not follow any of the good lifestyle factors to 10.10% (95% CI: 7.90% to 12.30%) among those with ≥4 good lifestyle factors.

Other studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of healthy lifestyle factors on the predictors of HF. Chiuve et al 17 in their analysis of Health Professionals Follow-up Study demonstrated a beneficial effect of eating a prudent diet, regular exercise, managing weight, and abstinence from smoking to significantly reduce the risk of CHD, an important risk factor for HF, by improving lipids, blood pressure, and other risk factors. Similar beneficial effects of healthy lifestyle factors on CHD have also been demonstrated by other investigators 18–21.

In a recent cross sectional study 22, a lack of adherence to healthy lifestyle factors (diet, exercise frequency, smoking status, and alcohol consumption) was inversely related to failure in achieving desirable blood pressure goals. A study of elderly individuals 23 demonstrated a beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on the incidence of DM irrespective of beverage type. Kochar et al 24 reported an inverse association between breakfast cereals, especially whole-grain products and incident DM.

However, no prior study has directly looked into how much of the HF risk can be attenuated by adopting such healthy lifestyle factors among individuals already at a high risk with a parental history of premature MI, an indication of genetic susceptibility. The results of our study suggest that maintenance of healthy habits known to lower the HF risk remain essential even among individuals at higher risk of developing HF with antecedent MI.

Our findings have direct clinical implications in that if confirmed in other populations, a simple medical history could help identify patients at risk of HF with antecedent MI for aggressive follow up and management of co-existing risk factors. Our study has some limitations. First, parental history of MI and age at parental MI were self-reported. Inaccurate recall or misclassification could have biased our results. However, since such information was collected prior to HF occurrence, any exposure misclassification is more likely to have been non-differential and bias the results towards the null. Second, participants in this study were male mostly Caucasian physicians, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups or in female gender. Third, in the absence of randomization, we cannot exclude chance, confounding by unmeasured factors, or residual confounding as possible explanation for our findings. Fourth, we were unable to account for early lifestyle factors for men who entered the study at an older age (>75 y) despite the long duration of follow up. Lastly, we did not have enough subjects >80 years at entry for stratified analysis. Nevertheless, the large sample size, more than 20-years of follow up, the standardized and systematic collection and validation of endpoints in the PHS are strengths of this study.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the participants in the PHS for their outstanding commitment and cooperation and to the entire PHS staff for their expert and unfailing assistance.

Grants funding and role of the funding source: This study was supported by grants R01 HL092946 and HL092946-S1 (to Dr Djoussé) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD.

The Physicians’ Health Study is supported by grants CA-34944, CA-40360 and CA-097193 from the National Cancer Institute and grants HL-26490 and HL-34595 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD. Funding agencies play no role in the data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgement to all contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship: N/A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:129–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christen WGGJ, Hennekens CH. Design of Physicians’ Health Study II--a randomized trial of beta-carotene, vitamins E and C, and multivitamins, in prevention of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and eye disease, and review of results of completed trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djousse LGJ. Alcohol consumption and risk of heart failure in the Physicians’ Health Study I. Circulation. 2007;115:34–39. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.661868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djoussé LDJ, Gaziano JM. Relation between modifiable lifestyle factors and lifetime risk of heart failure: The Physicians’ Health Study I. JAMA. 2009;302:394–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizer AGJ, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Albert CM. Relation of Vigorous Exercise to Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1572–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatkin DMC, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ, Jr, Spudich S, De Girolami U, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Muntoni F, Müehle G, Johnson W, McDonough B. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1715–1724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasotti MRA, Tavazzi L, Arbustini E. Genetic predisposition to heart failure. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:1173–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weder AB. Genetics and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007 Mar;9(3):217–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafar-Mohammadi BMM. Genetics of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity - a review. Ann Med. 2008;40:2–10. doi: 10.1080/07853890701670421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kullo IJDK. Mechanisms of disease: The genetic basis of coronary heart disease. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4:558–569. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatkin DOR, Vandenberg JI. Genes and atrial fibrillation: a new look at an old problem. Circulation. 2007;116:782–792. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.688889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett DKdlF, Broeckel U. Genes for left ventricular hypertrophy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2004;6:36–41. doi: 10.1007/s11906-004-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstone APBP. Genetic obesity syndromes. Front Horm Res. 2008;36:37–60. doi: 10.1159/000115336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith NLFJ, Morrison AC, Demissie S, Glazer NL, Loehr LR, Cupples LA, Dehghan A, Lumley T, Rosamond WD, Lieb W, Rivadeneira F, Bis JC, Folsom AR, Benjamin E, Aulchenko YS, Haritunians T, Couper D, Murabito J, Wang YA, Stricker BH, Gottdiener JS, Chang PP, Wang TJ, Rice KM, Hofman A, Heckbert SR, Fox ER, O’Donnell CJ, Uitterlinden AG, Rotter JI, Willerson JT, Levy D, van Duijn CM, Psaty BM, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS. Association of genome-wide variation with the risk of incident heart failure in adults of European and African ancestry: a prospective meta-analysis from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:256–266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.895763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Djoussé LGJ. Parental history of myocardial infarction and risk of heart failure in male physicians. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:896–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DSPM, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Nam BH, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Association of parental heart failure with risk of heart failure in offspring. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:138–147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiuve SEMM, Sacks FM, Rimm EB. Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men: benefits among users and nonusers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation. 2006;114:160–167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stampfer MJHF, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusuf SHS, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djoussé LAD, Carr JJ, Eckfeldt JH, Hopkins PN, Province MA, Ellison RC Investigators of the NHLBI FHS. Dietary linolenic acid is inversely associated with calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries: the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;111:2921–2926. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.489534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djoussé LPJ, Eckfeldt JH, Folsom AR, Hopkins PN, Province MA, Hong Y, Ellison RC. Relation between dietary linolenic acid and coronary artery disease in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:612–619. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokokawa HGA, Sanada H, Watanabe T, Felder RA, Jose PA, Yasumura S. Achievement status toward goal blood pressure levels and healthy lifestyles among Japanese hypertensive patients; cross-sectional survey results from Fukushima Research of Hypertension (FRESH) Intern Med. 2011;50:1149–1156. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djousse LBM, Mukamal KJ, Siscovick D. Alcohol Consumption and Type 2 Diabetes Among Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Obesity. 2007;15:1758–1765. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochar JDL, Gaziano JM. Breakfast cereals and risk of type-2 diabetes in the Physicians’ Health Study I. Obesity. 2007;15:3039–3044. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]