Abstract

We reviewed literature examining predictors of urinary fistula repair outcomes in developing country settings, including fistula and patient characteristics, and peri-operative factors. We searched Medline for articles published between January 1970 and December 2010, excluding articles that were 1) case reports, cases series or contained 20 or fewer subjects; 2) focused on fistula in developed countries; and 3) did not include a statistical analysis of the association between facility or individual-level factors and surgical outcomes. Twenty articles were included; 17 were observational studies. Surgical outcomes included fistula closure, residual incontinence following closure, and any incontinence (dry vs. wet). Scarring and urethral involvement were associated with poor prognosis across all outcomes. Results from randomized controlled trials examining prophylactic antibiotic use and repair outcomes were inconclusive. Few observational studies examining peri-operative interventions accounted for confounding by fistula severity. We conclude that a unified, standardized evidence-base for informing clinical practice is lacking.

Keywords: Developing countries, obstetric fistula, surgical outcomes, systematic review

Introduction

An obstetric fistula, or abnormal opening between the vagina and the bladder or rectum, is a devastating condition. It is caused by prolonged obstructed labor: the fetus’s head compresses soft tissues of the bladder, vagina and rectum against the woman’s pelvis, cutting off blood supply, causing these tissues to die and slough away. It can result in urinary or fecal incontinence, or both; concomitant conditions may include painful rashes resulting from constant urine leakage, amenorrhea, vaginal stenosis, infertility, bladder stones, and infection.1 Women suffering from obstetric fistula may be abandoned by their husbands and ostracized by their communities. While global prevalence is unknown, the self-reported lifetime prevalence of fistula symptoms reported in Demographic and Health Surveys has ranged from .4% in Nigeria2 to 4.7% in Malawi.3

Less frequently, genito-urinary and rectovaginal fistulas may result from sexual violence, malignant disease, radiation therapy, or surgical injury (most often to the bladder during hysterectomy or Caesarean section (C-section)). Surgical injury, malignant disease and radiation therapy, are the predominant cause of the condition in industrialized countries; indeed, obstetric fistula rarely occurs in settings where competent emergency obstetric care is readily accessible. Fistulas resulting from surgical injury are characterized by discrete wounding of otherwise normal tissue1 while both obstructed labor and radiation may lead to extensive ischemia and scarring.

There are two broad research priorities in the vaginal fistula (hereafter referred to as “fistula”) repair field. One is to evaluate which operative techniques and methods of perioperative patient management are most effective and efficient for fistula closure and prevention of residual incontinence following successful closure. Many fistula surgeons have developed their own methods through experience4 and thus a wide variety of procedures and methods are commonly used. The other need is for evidence to support the development of a standardized evidence-based system for classifying fistula prognosis, and at a minimum, a system prognostic for fistula closure. Currently at least 25 systems are used5 and parameters measured by these classification systems vary greatly. To-date, the prognostic value of only two systems6-7 has been tested; these analyses were conducted following the adoption of these systems, rather than to create them. In order to develop a prognostic system, it is necessary to determine which patient and fistula characteristics independently predict outcomes, and to identify the minimal parameters required for accurate prognosis, since the simpler a classification system, the more likely it is to be used. A prognostic classification system would not only facilitate the evaluation of surgical success rates across facilities, but also the effectiveness of interventions independent of confounding by patient or fistula characteristics; it would also facilitate the comparative analysis of studies that examine treatment outcomes.

In light of the above priorities, and increased research on obstetric fistula in recent years, we aimed to systematically review and synthesize the evidence regarding factors that may influence fistula repair outcomes in developing countries, including fistula and patient characteristics, as well as peri-operative factors (e.g. peri-operative procedures and other aspects of service delivery). Based on these findings, our goal was to identify future research priorities in order to fill existing knowledge gaps.

Methods

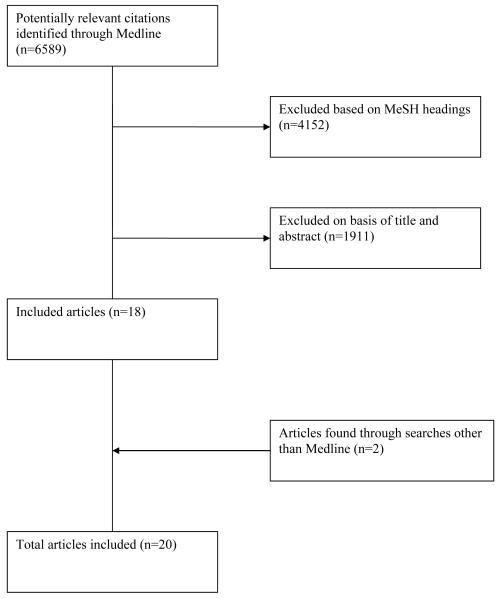

We conducted a systematic review of the Medline database to identify relevant publications by searching for articles published from 1970-2010, using the following topic headings: “obstetric fistula,” “vaginal fistula,” “urinary bladder fistula,” “vesicovaginal fistula” and “fistula”; this yielded 6,589 articles. The search was refined by excluding the MeSH headings clearly unrelated to the female genital fistula of interest, namely “infant,newborn,” “male,” “kidney transplantation,” “adenocarcinoma,” “radiotherapy,” “penis,” “animals,” “prostatectomy,” “Crohn’s Disease” “child, preschool” “radiation injuries,” and “kidney diseases.” This yielded 2,437 articles. We reviewed titles of these articles excluding those clearly not meeting our eligibility criteria. This resulted in 526 articles whose abstracts were reviewed to determine eligibility.

Articles included in the final analysis met the following criteria: peer reviewed; original research; focused on predictors of fistula repair outcomes; published after 1970; and written in French or English. Articles were excluded if they were case reports, cases series or contained 20 or fewer subjects; focused on fistula in developed countries (since most of these are secondary to surgery or malignancy, and results from such studies may not be generalizable to developing countries where obstetric fistula predominates); and did not statistically analyze associations between predictors and surgical outcomes. Review of references of published papers yielded one additional article that met the inclusion criteria. One additional article was identified via an internet search engine (Google).(Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study eligibility

Twenty articles examining predictors of fistula surgery outcomes were identified (Table 1), and data on sample characteristics, study design, exposures, outcomes, and effect estimates were abstracted by one author. Fourteen studies reported results of retrospective record reviews,8-21 three were prospective studies,6-7, 22 and three were randomized controlled trials (RCTs).23-25 A minority of the observational studies6-7, 9, 17-19 accounted for potential confounding with multivariate analysis. Sample sizes ranged from 34-1045; half had samples over 1006-9, 11, 13, 17-19, 24 and one-quarter had samples under 50.14-16, 25 Studies examined a variety of predictors (Table 2): eight examined patient or fistula characteristics,6-10, 15, 21-22 six examined peri-operative factors,11-15, 20, 24 and five examined both.16-19, 25 Three studies were restricted to women undergoing primary repairs.7, 17, 24

Table 1.

Publications examining predictors of fistula repair outcomesin developing country settings

| Author, Year |

Study Design |

Population | Sample size |

Outcome definition | Exposures of interest | Analytic approacha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirschner et al., 201019 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with vesicovaginal fistula; where unit of analysis was individual patient, analyses were restricted to women undergoing first repair |

1084 records from 926 patients |

Continence (dry vs wet), assessed at time of discharge |

Patient characteristics (age at surgery, education, parity, number of living children, literacy, language group and marital status), clinical data (cause of fistula and number of previous surgeries) and surgical data (type/location of fistula, degree of fibrosis, surgical approach, and procedures performed) |

Independent sample t-tests and Chi-square tests GEE bivariate and multivariate regression. Multivariate models adjusted for confounding by days in labor, number of living children, marital status, months with fistula and place of delivery |

| Muleta et al., 201024 |

RCT | Patients with obstetric fistula undergoing first repair |

722 patients |

Fistula closure, assessed after catheter removal and prior to discharge |

Single-dose Gentamycin vs. extended antibiotic use. Extended antibiotic use included any one or combination of Amoxicillin (500mg IV and oral 6 hourly), chloramphenicol (500mg IV and oral 6 hourly), or co-trimexazole (800mg orally every 12 hours) for 7 days |

Chi-square, risk difference |

| Nardos et al., 200917 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric vesicovaginal fistula undergoing first repairs via vaginal route |

1045 patients |

Fistula closureb, assessed after catheter removal and prior to discharge |

Extent of urethral destruction, circumferential damage, extent of scarring, residual bladder size, repair technique (single vs double layer closure) |

Logistic bivariate and multivariate regression |

| Lewis et al. 20099 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with genitourinary fistula |

505 records from 435 patients |

Continence (dry vs. wet), assessed via subjective appraisal after catheter removal and prior to discharge |

Patient demographics (age), obstetric history (index pregnancy), and fistula parameters (number of prior repairs, fistula type, site and size, degree of fibrosis, and urethral status |

Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank sum test; bivariate analyses stratified by primary vs. subsequent repair GEE multivariate regression |

| Olusegun et al. 200915 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with vesicovaginal fistula |

37 patients | Continence (dry vs. wet) at discharge (personal communication H. Onah, July 2011) |

Duration of fistula before repair | Chi-square |

| Safan et al. 200925 |

RCT | Patients with complicated fistula (defined as recurrence, local moderate to severe fibrosis, fistula location involving the bladder neck, and or size of the fistula being more than 1.5 cm in largest diameter) |

38 patients | Continence (dry vs. wet), assessed at three months follow-up |

Primary exposures were fibrin glue vs martius flap as interpositioning layer. Also examined parity, patient age, attempts of previous repairs, fistula size, and fistula location |

Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact tests |

| Goh et al. 20086 |

Prospective | Patients with genitourinary fistula (women with rectovaginal fistula only or no bladder tissue excluded) |

987 patients |

Fistula closure and residual urinary incontinence following successful closure, assessed after catheter removal and prior to discharge |

Components of Goh’s classification system: Fistula type (characterized by distance of fistula from external urinary meatus), size, “special considerations” (extent of fibrosis and vaginal length, and special circumstances such as previous repair, ureteric involvement, etc) |

Chi-square test and logistic multivariate regression (residual incontinence only) |

| Morhason- Bello et al. 200820 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with midvaginal fistulas with no fibrosis, evidence of infection, urethral or bladder neck involvement and more than one previous repair attempt |

71 patients | Continence three months following surgery |

Abdominal versus vaginal route of repair |

Fisher’s exact test |

| Nardos et al. 200813 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric fistula (women with rectovaginal fistula only excluded) |

212 patients |

Fistula closure and residual incontinence, assessed after catheter removal and prior to discharge (differences at 6- month follow-up not tested) |

3 duration of catheterization groups: 10 days (group 1), 12 days (group 2), and 14 days (group 3) |

Unspecified (chi-square assumed); bivariate analyses stratified by components of Goh classification system |

| Raassen et al. 20087 |

Prospective | Patients with obstetric fistula undergoing first- time repair |

581 patients |

Fistula closure assessed via dye test prior to catheter removal (14-21 days following surgery) and residual urinary incontinence following successful closure assessed after catheter removal prior to discharge |

Patient characteristics (age and duration of leakage) and components of Waaldijk classification system (type of fistula characterized by extent of involvement of closing mechanism and presence of circumferential defect, exceptional fistulas and size) |

Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact tests and logistic multivariate regression (closure only) |

| Holme et al. 20078 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric fistula |

259 patients |

Closure, not closed, residual incontinence; time period unspecified |

Scarring | Spearman correlation |

| Browning 200611 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric fistula (women with rectovaginal fistula only excluded) |

413 repairs | Fistula closure assessed via dye test prior to catheter removal (14-21 days following surgery) and residual urinary incontinence following successful closure assessed after catheter removal prior to discharge |

Martius graft | Fisher’s Exact test or Chi-Square with continuity correction; bivariate analyses stratified by components of Goh classification system and other fistula characteristics |

| Browning 200618 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric fistula (women with breakdown of repair, lack of bladder tissue and rectovaginal fistula only excluded) |

481 women | Residual incontinence following fistula closure, assessed following catheter removal and prior to discharge |

Urethral involvement, repeat surgery, size of fistula, size of bladder, location of ureter, scarring, flap required, presence of rvf, number of vvf, age, parity, duration labor, time since delivery, diameter of fistula, delivery method and outcome of delivery |

T-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and logistic multivariate regression |

| Chigbu et al. 200612 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with juxtacervical vesicovaginal fistula |

78 women | Fistula closure at either 6 weeks or 3 months (personal communication H. Onah, July 2011) |

Route of repair (vaginal vs. abdominal) |

T-tests and Chi-square tests |

| Melah et al. 200610 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with vesicovaginal fistula |

80 women | Fistula closure and residual incontinence following closure; time period of assessment unspecified |

Early (less than 3 months) vs. late (after 3 months) closure |

Chi-square |

| Kriplani et al. 200516 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with genital fistula (radiation fistulas excluded) |

34 women | Continence following catheter removal |

Age, parity, duration of fistula, route of repair, etiology |

Levene’s test of equality of variances and Chi square with Yates correction |

| Murray et al. 200221 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with obstetric fistula |

55 women | Residual incontinence following fistula closure, assessed between four weeks and three months following repair |

Mean fistula diameter | Wilcoxon signed rank sum test |

| Rangnekar et al. 200014 |

Retrospective record review |

Patients with urinary-vaginal fistulas (excluded fistulas situated high on the posterior wall of the bladder and fistulas greater than 1.5cm in size) |

46 women | Fistula closure assessed via dye test prior to catheter removal and residual incontinence following closure, assessed with urodynamic test 3 weeks postoperatively. |

Martius flap repair | Fisher’s exact test |

| Tomlinson and Thornton 199823 |

RCT | Patients with obstetric vesico- vaginal fistula |

79 women | Fistula closure and continued incontinence (positive pad test) at hospital discharge. |

500 mg ampicillin | Mann-Whitney (non-parametric tests) |

| Bland and Gelfand 197022 |

Prospective | Patients with vesicovaginal fistula |

60 women | Closed fistula 6 weeks after repair |

Urinary bilharziasis defined by presence of ova on bladder biosopsy or urine examination or rectal snip |

Chi square with Yates correction |

Only the analytic approach for the outcome of interest is reported

Unless otherwise specified, fistula closure was assessed using dye test if the patient reported urine leakage

Table 2.

Predictors studied across the articles reviewed,a by study outcome and results

| Predictor | Closure | Residual incontinence | Any incontinence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influence | No influence/ inconclusiveb |

Influence | No influence/ inconclusive |

Influence | No influence/ inconclusive |

|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||

| S. haematobium | 22 | |||||

| Age at fistula repair | 7 | 18, 7 | 9, 16, 19, 25 | |||

| Age at fistula occurrence | 9, 19 | |||||

| Duration of fistula | 10, 7 | 10, 18, 7 | 15, 16, 19c | |||

| Parity | 18 | 9, 16, 19, 25 | ||||

| Number living children | 19 | |||||

| Mode of delivery | 18 | 19 | ||||

| Days in labor | 19 | |||||

| Education | 19 | |||||

| Literacy | 19 | |||||

| Place of delivery | 19 | |||||

| Fistula characteristics | ||||||

| Etiology | 16 | |||||

| Number of fistulas | 18 | 19 | ||||

| Fistula size | 6, 7 | 6, 18 | 7, 21 | 9, 16, 19, 25 | ||

| Scarring | 17 | 6, 8 | 6d, 18 | 8 | 9, 19 | |

| Bladder size | 17 | 18 | ||||

| Bladder neck / circumferential fistula |

19 | |||||

| Extent of urethral involvement / circumferential fistula |

17 | 6, 7 | 6, 18 | 7 | 19 | 9 |

| Ureteric involvement | 7 | 7 | 9 | |||

| Other fistula location (“low”, juxtacervical, etc) |

19 | 9, 25 | ||||

| Combined vvf/rvf | 7 | 18 | 19 | |||

| Previous repair | 18 | 9, 16, 25 | ||||

| Peri-operative factors | ||||||

| Abdominal vs vaginal surgical route |

12 | 16, 20e | ||||

| Catheter for 10, 12, 14 days | 13 | 13 | ||||

| Single (vs. double) layer closure |

17 | |||||

| Relaxing incision | 19 | |||||

| Martius fibrofatty flap/graft | 11, 14 | 11 | 19 | |||

| Martius graft (vs fibrin glue) |

25 | |||||

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | 23 | 23 | ||||

| Single dose (vs extended antibiotics) |

24 | |||||

Articles indicated by reference number

Factors evaluated in an observational study using bivariate analyses only, not significant (p>.05) in bivariate analysis of RCT data or not significant (p>.05) in multivariate analysis of observational data

Outcome confirmed via personal communication with primary author

Categorized as part of “special considerations” in the Goh classification system

Outcome examined confirmed via personal communication with primary author

Definitions of “successful repair” varied, including fistula closure, no residual incontinence among those with closed fistula, or no incontinence (i.e. fistula closure and no residual incontinence) (Table 2). Most studies assessed associations between predictors and repair outcomes at discharge (typically 2-3 weeks after repair). There were several exceptions. Bland and Gelfand assessed outcome at six weeks following repair.22 Safan and colleagues25 and Morhason-Bello and colleagues20 examined outcome three months following repair, and Chigbu et al. assessed outcome at 6 weeks or 3 months after repair, depending on data availability (personal communication H. Onah, July 2011).12 For those studies for which we were unable to determine timing of outcome assessment8, 10, 12, 15-16 we assume that outcome was assessed at discharge.

Results

The relationship between patient characteristics and surgical outcomes

Age at repair was the most common characteristic studied; however, neither age at repair nor age at fistula occurrence predicted repair prognosis independent of other fistula or patient characteristics. Evidence to support the role of parity, duration of leakage, and mode of delivery on repair outcomes was similarly weak, and in the case of parity, contradictory. In bivariate analysis, Lewis et al.9 found that higher parity predicted any incontinence, while Browning18 and Kirschner19 found that lower parity reduced the risk of negative outcomes. These associations were not significant in multivariate analysis, however. Other factors related to the causative delivery or obstetric history were evaluated by only one study, in unadjusted analyses.19 Finally, the only patient comorbidity evaluated was urinary bilharziasis. Bland and Gelfand (1970) examined the association between Schistosoma haematobium and fistula closure, hypothesizing that bladder wall fibrosis caused by urinary bilharziasis complicates closure and healing. Indeed, 70% of S. haematobium negative patients healed successfully, compared to 37.5% of those positive.22 The study was small, and only unadjusted associations were tested.

The relationship between fistula characteristics and surgical outcomes

In contrast to patient characteristics, stronger evidence supports the negative influence of fistula characteristics, particularly vaginal scarring and urethral involvement (including circumferential damage, i.e. complete separation of the urethra from the bladder), on repair outcomes. Each of the studies examining vaginal scarring found an association with repair outcome, including multivariate analyses demonstrating an independent effect of vaginal scarring on closure (OR=2.67, 95%CI: 1.36-3.75),17 residual stress incontinence following closure (OR=2.4, 95%CI: 1.5-4.0)18 and any incontinence (OR=3.21, 95%CI: 2.10-4.89).19 One study found a dose-response, with higher degree of scarring resulting in greater likelihood of any incontinence.9 Similarly, three large studies found an independent association between increased degrees of urethral involvement and failure to close the fistula (OR=1.56, 95%CI: 0.94-2.59),17 residual incontinence(OR=8.4, 95%CI: 3.9-17.9)26 and any incontinence (OR=3.58, 95%CI: 2.42-5.31 and OR=8.04, 95%CI: 3.18-20.31 for partial and complete loss of the urethra, respectively).19 The latter study also found that “lower” fistulas (urethra-vaginal, circumferential, juxta-urethral, fistula behind the symphisis pubis) and “large” fistulas (entire anterior vagina destroyed) were significantly associated with incontinence.19 Finally, a smaller study found a marginal association (OR=2.41; p=.08) between partial urethral damage, and no association between complete urethral destruction, and any incontinence.9

One large study found that as fistula size increased, the likelihood of residual incontinence decreased, after adjusting for other fistula and patient characteristics (OR=1.34, 95%CI: 1.16-1.56),26. The only study7 examining fistula diameter, however, found no association with fistula closure. Both studies examining the association between bladder size and repair outcomes found that smaller size independently predicted failure to close the fistula (OR=2.27, 95%CI: 1.36-3.75)17 and incontinence following closure (OR=4.1, 95%CI: 1.2-13.8).18 Finally, evidence was insufficient regarding the role of prior repair, ureteric involvement, combined VVF/RVF or multiple fistulas on repair outcomes.

Components of two existing classification systems have been correlated (post-development) with patient outcomes. One study examined the influence of Goh’s classification system components (Table 3) on incontinence following successful closure, independent of other components of the classification system (no multivariate analyses were conducted to assess independent predictors of closure). Women with Type 1 fistulas (fistulas furthest from the urethral opening) were more likely to be continent than women with Type 4, with a trend towards decreasing continence from Type 2 to 4. Women with larger fistulas, and those with special considerations (including scarring), were less likely to be continent.6 These findings corroborate those on urethral involvement and scarring discussed above, and contribute evidence regarding the role of fistula size on residual incontinence. Raassen and colleagues tested the ability of components of Waaldijk’s classification system (Table 3) to predict fistula closure and residual incontinence among 581 fistula patients. Multivariate analyses assessed predictors of closure only, and revealed no independently predictive components.7

Table 3.

Waaldijk and Goh fistula classification systems

| Classification system |

Type and / or description of fistula | |

|---|---|---|

| Waaldijk 199529 | Classification | Size |

| Type 1 Not involving the closing mechanism |

Small <2 Medium 2-3 |

|

| Type 2 Involves closing mechanism | Large 4-5 | |

| A Without (sub)total urethra involvement |

Extensive> 6 | |

| B With (sub)total urethra involvement | ||

| a Without circumferential defect | ||

| b With circumferential defect | ||

| Type 3 Ureteric and other exceptional fistula |

||

|

| ||

| Goh 200430 | Type: distance from fixed reference point | |

| Type 1 Distal edge of the fistula >3.5 cm from external urinary meatus | ||

| Type 2 Distal edge of the fistula 2.5-3.5 cm from external urinary meatus | ||

| Type 3 Distal edge of the fistula 1.5-<2.5 cm from external urinary meatus | ||

| Type 4 Distal edge of the fistula <1.5 cm from external urinary meatus | ||

| Size: largest diameter in centimetres | ||

| a Size <1.5 cm in the largest diameter | ||

| b Size 1.5-3 cm in the largest diameter | ||

| c Size >3 cm in the largest diameter | ||

| Special considerations | ||

| i. None or only mild fibrosis (around fistula and/or vagina) and/or vaginal length >6cm, normal bladder capacity |

||

| ii. Moderate or severe fibrosis (around fistula and/or vagina) and/or reduced vaginal length and/or bladder capacity |

||

| iii. Special circumstances, e.g. post-radiation, ureteric involvement, circumferential fistula, previous repair |

||

The relationship between peri-operative factors and surgical outcomes

Evidence is sparse regarding the effectiveness of peri-operative factors on repair outcomes. Two RCTs examining antibiotic use23-24 had indeterminate findings. Tomlinson and Thornton examined whether intra-operative intravenous ampicillin reduced the failure rate of VVF repair. The authors hypothesized that reducing surgical wound infections improves fistula healing; however, they actually found a trend towards higher failure to heal1 and more incontinence in the intervention group (OR=2.1, 95%CI: 0.75-6.1).23 More recently, Muleta and colleagues examined the effects of either 80 mg Gentamycin IV or extended use of Amoxicillin, chloramphenicol or cortimexazole on fistula closure, finding that the Gentamycin arm trended toward higher closure rates (94% vs. 89.4%, p=.04; risk difference (RD)=5.1%, 95%CI: −0.4-10.6).24

Four studies examined the effect of Martius flap interpositioning, with conflicting results. Only one 14 found a positive effect on fistula closure; it was small and reported only unadjusted associations. While another found the Martius Flap to be associated with significantly higher risk of residual incontinence after repair among all fistulas, urethral fistulas only and Goh Type 2 fistulas,11 analyses did not adjust for multiple confounding factors simultaneously. Three retrospective studies examined route of repair12, 16, 20; they were small, detected varying directions of effect, and reported only unadjusted associations (though two12, 20 restricted the sample by type of fistula). The only study examining double-versus single-layer closure found no association after adjusting for bladder size (OR=1.17, 95%CI: 0.73-1.87), and relaxing incision was associated with incontinence (OR=1.91, 95%CI: 1.25-3.11), controlling for a limited set of fistula characteristics.19 Finally, one study examined the unadjusted influence of duration of bladder catheterization on repair outcomes: patients catheterized for 12 and 14 days had significantly greater likelihood of residual incontinence than those catheterized for 10 days; no difference in closure was detected.13 No other studies of peri-operative procedures, nor any studies examining the influence of repair context or provider experience on repair outcomes, have been published.

Conclusion

We systematically reviewed literature examining predictors of fistula repair outcomes. Most studies were observational, and few conducted analyses that would permit assessment of independent effects of individual predictors. Patient and fistula characteristics were most frequently studied, with multiple studies of some predictors. Studies of peri-operative factors have been less frequently replicated.

Evidence in the published literature failed to demonstrate an independent role of patient characteristics in predicting repair outcome. The relationship between some patient characteristics and repair outcomes may be mediated by fistula characteristics. For instance age is related to pelvic size, and may thereby influence the degree of damage caused by the obstructed labor, in turn influencing the prognosis of the repair. The influence of patient comorbidities on repair outcomes has rarely been studied; further evaluation is warranted, as comorbidities may be addressed pre-operatively.

Unlike patient characteristics, the weight of evidence indicates that certain fistula characteristics, particularly scarring and urethral involvement, predict poor repair prognosis. These findings are biologically plausible. Urethral fistula repair is a complex procedure. It necessitates reconstruction of surviving tissues into a supple functional organ, which acts both as a passageway for urine, and as a “gatekeeper,” ensuring that passage of urine occurs at appropriate times.27 Reconstruction of the urethra may not necessarily re-establish normal physiology of urethral function and the urethral/bladder voiding reflex. Extensive scarring not only inhibits access to the fistula, but requires use of unhealthy tissue to close the defect.27 Vaginal scarring can also lead to incontinence, if it prevents normal urethral functioning.18

The relationship between other fistula characteristics and repair outcomes is less clear. While two large studies found that as fistula size increases, likelihood of continence following fistula closure decreases,6, 18 the samples of the two studies overlapped somewhat (personal communication A. Browning, July 2011). Nonetheless, these findings are not surprising. It has been suggested that more extensive dissection which may be required for larger fistulas can cause post-operative scarring around the urethra, holding the urethra open.18 The results of two studies showing an association between smaller bladder size and failure of fistula closure24 and incontinence following closure,18 are also biologically plausible. Loss of bladder tissue means the surgeon must close defects with limited remnants of (frequently damaged) bladder tissue; the small resulting bladder size may affect its capacity to retain urine. In addition, while no studies detected an independent association of prior repair and repair outcomes, prior repair has been correlated with degree of vaginal scarring.8 Thus, prior repair may be an indirect cause of negative repair outcomes, via vaginal scarring, which could explain the lack of an independent role of prior repair after adjusting for vaginal scarring seen in two studies.9, 18 Additional studies with large sample sizes are needed to study relatively rare exposures such as ureteric involvement.

Few studies have examined the role of peri-operative factors and all but three were observational designs. Results of the three RCTs 23-25 are difficult to interpret. The findings that prophylactic antibiotic use trended towards higher operative failure and more incontinence compared to no antibiotic use are surprising and counter-intuitive, given the expectation that reducing wound infections would promote fistula closure.23 A recent trial comparing single-dose versus extended antibiotic use demonstrate a marginally significant benefit in favor of single-dose antibiotics, though reasons for such a trend are unclear.24 However, the confidence intervals for both results were compatible with a chance result. The RCT comparing fibrin glue to Martius flap interpositioning was inconclusive, due to its small sample size.25

Observational studies examining medical interventions are subject to confounding by indication, or prognosis, whereby providers prescribe vigorous therapy when the outlook is poor.28 This applies to the observational studies examining peri-operative factors related to fistula surgery, reviewed here. For instance, Nardos et al.13 demonstrated that women catheterized for fewer days were significantly more likely to have fistula characteristics associated with a favorable repair prognosis. Similarly, while Kriplani and colleagues16 found a significantly higher proportion success among fistulas repaired vaginally, analyses did not account for the severity of the fistula, and it is possible that abdominal repairs were more difficult cases less likely to be successfully repaired. In addition, while Kirschner and coauthors found that use of relaxing incision was associated with poorer prognosis, analyses did not adjust for scarring and stenosis, factors that the authors acknowledge may have indicated use of relaxing incision.19

Several observational studies restricted their samples to women meeting specific criteria. Though preferable to no adjustment, this does not allow for adjustment of multiple confounding factors. For instance, while Browning11 found that a significantly higher proportion of women with a Martius flap experienced residual incontinence after repair, stratified analyses demonstrated that fistulas repaired with Martius flap may have been more difficult. Though differences persisted within select subgroups, the possibility of residual confounding by indication cannot be excluded.11

We have identified several research priorities. First, the endpoint “any incontinence,” does little to inform intervention efforts, since the causes of failure to close a fistula versus causes of residual incontinence cannot be teased out. Future studies should examine fistula closure and residual incontinence separately, in order to clarify the etiological importance of different characteristics and procedures being studied. Where possible, studies examining residual incontinence should employ urodynamic studies (UDS) to enable differentiation between types of incontinence, including stress, urge, overflow and mixed incontinence.

Secondly, post-hoc studies of the predictive value of an individual classification system cannot determine the sufficiency of the systems for predicting repair outcomes, or the superiority of one system over another. For instance, it is possible that patient or fistula characteristics not included in current classification systems are important in predicting repair outcomes. Similarly, the inability of any component of these systems to predict fistula closure may result from inadequate statistical power to detect small differences. In order to develop a single, standardized prognostic system for classifying fistulas, additional research confirming the prognostic value of parameters included in existing classification systems, as well as evaluating factors not included, is needed. It is also important to compare existing classification systems to assess their relative discriminatory value for predicting repair outcomes.

More research is also required to assess which peri-operative factors are associated with repair outcomes, independent of patient or fistula characteristics. In particular, further research is required on factors such as duration of catheterization and route of repair which may be associated with increased hospital stay and risk of health-care associated infection. A standardized system of classifying fistula prognosis will facilitate the conduct of such studies.

In summary, a small, albeit growing, number of empirical studies have examined the relationship between fistula repair outcomes and patient characteristics, fistula characteristics and peri-operative procedures used. Many of the studies we reviewed had relatively small sample sizes and did not use rigorous epidemiologic research methods. This, together with the range of predictors studied and variety of definitions of repair outcomes used, has resulted in lack of a unified evidence-base on most predictor-repair outcome relationships and thus little evidence on which to base clinical practice. Given the material and human resource shortages in the settings in which fistula surgery is often conducted, it is admirable that any data has been accumulated on this patient population. Nonetheless, further research is urgently needed to improve the care and treatment of this marginalized and neglected group of women.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Elaine Larson, Guohua Li and Leslie Davidson from Columbia University, and Erin Mielke from USAID, for their thoughtful reviews of the manuscript.

Sources of financial support: This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) which supported the first author’s doctoral research, as well as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of associate cooperative agreement GHS-A-00-07-00021-00. The information provided here does not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. government.

Footnotes

We understand heal to refer to fistula closure, given that the proposed mediating mechanism between antibiotic use and surgical outcome was reducing surgical wound infection

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Presentation information: This work was presented in part at the 2010 International Society of Fistula Surgeons (ISOFS) conference, 9 December 2010, in Dakar Senegal.

References

- 1.Wall LL. Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public-health problem. Lancet. 2006;368:1201–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Population Commission (NPC), ORC Macro . Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. NPC and ORC Macro; Calverton, Maryland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Statistical Office (NSO), ORC Macro . Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. NSO and ORC Macro; Calverton, Maryland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browning A. The circumferential obstetric fistula: characteristics, management and outcomes. BJOG. 2007;114:1172–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creanga AA, Genadry RR. Obstetric fistulas: a clinical review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh JT, Browning A, Berhan B, Chang A. Predicting the risk of failure of closure of obstetric fistula and residual urinary incontinence using a classification system. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1659–62. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raassen TJ, Verdaasdonk EG, Vierhout ME. Prospective results after first-time surgery for obstetric fistulas in East African women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:73–9. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holme A, Breen M, MacArthur C. Obstetric fistulae: a study of women managed at the Monze Mission Hospital, Zambia. BJOG. 2007;114:1010–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis A, Kaufman MR, Wolter CE, et al. Genitourinary fistula experience in Sierra Leone: review of 505 cases. J Urol. 2009;181:1725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melah GS, El-Nafaty AU, Bukar M. Early versus late closure of vesicovaginal fistulas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93:252–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Browning A. Lack of value of the Martius fibrofatty graft in obstetric fistula repair. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chigbu CO, Nwogu-Ikojo EE, Onah HE, Iloabachie GC. Juxtacervical vesicovaginal fistulae: outcome by route of repair. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26:795–7. doi: 10.1080/01443610600984651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nardos R, Browning A, Member B. Duration of bladder catheterization after surgery for obstetric fistula. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:30–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rangnekar NP, Ali N Imdad, Kaul SA, Pathak HR. Role of the martius procedure in the management of urinary-vaginal fistulas. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:259–63. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olusegun AK, Akinfolarin AC, Olabisi LM. A review of clinical pattern and outcome of vesicovaginal fistula. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:593–5. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30946-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriplani A, Agarwal N, Parul, Gupta A, Bhatla N. Observations on aetiology and management of genital fistulas. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271:14–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-004-0680-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardos R, Browning A, Chen CC. Risk factors that predict failure after vaginal repair of obstetric vesicovaginal fistulae. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:578, e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browning A. Risk factors for developing residual urinary incontinence after obstetric fistula repair. BJOG. 2006;113:482–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirschner C, Yost K, Du H, Karshima J, Arrowsmith S, Wall L. Obstetric fistula: the ECWA Evangel VVF Center surgical experience from Jos, Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal. 21:1525–33. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morhason-Bello IO, Ojengbede OA, Adedokun BO, Okunlola MA, Oladokun A. Uncomplicated midvaginal vesico-vaginal fistula repair in Ibadan: A comparison of the abdominal and vaginal routes. Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine. 2008;6:39–43. doi: 10.4314/aipm.v6i2.64051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray C, Goh JT, Fynes M, Carey MP. Urinary and faecal incontinence following delayed primary repair of obstetric genital fistula. BJOG. 2002;109:828–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bland KG, Gelfand M. The influence of urinary bilharziasis on vesico-vaginal fistula in relation to causation and healing. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1970;64:588–92. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(70)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomlinson AJ, Thornton JG. A randomised controlled trial of antibiotic prophylaxis for vesico-vaginal fistula repair. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:397–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muleta M, Tafesse B, Aytenfisu HG. Antibiotic use in obstetric fistula repair: single blinded randomized clinical trial. Ethiop Med J. 2010;48:211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safan A, Shaker H, Abdelaal A, Mourad MS, Albaz M. Fibrin glue versus martius flap interpositioning in the repair of complicated obstetric vesicovaginal fistula. A prospective multi-institution randomized trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:438–41. doi: 10.1002/nau.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Browning A. Prevention of residual urinary incontinence following successful repair of obstetric vesico-vaginal fistula using a fibro-muscular sling. BJOG. 2004;111:357–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Briggs ND, Browning A, Lassey A. The obstetric vesicovaginal fistula in the developing world. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:S3–S51. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200507001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology. 1996;7:335–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waaldijk K. Surgical classification of obstetric fistulas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;49:161–3. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(95)02350-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goh JTW. A new classification for female genital tract fistula. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:502–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]