Abstract

Arterial inflammation and remodeling, important sequellae of advancing age, are linked to the pathogenesis of age-associated arterial diseases, e.g., hypertension, atherosclerosis, and metabolic disorders. Recently, high-throughput proteomic screening has identified milk fat globule epidermal growth factor VIII (MFG-E8) as a novel local biomarker for aging arterial walls. Additional studies have shown that MFG-E8 is also an element of the arterial inflammatory signaling network. The transcription, translation, and signaling levels of MFG-E8 are increased in aged, atherosclerotic, hypertensive, and diabetic arterial walls in vivo as well as activated vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and a subset of macrophages in vitro. In VSMC, MFG-E8 increases proliferation and invasion as well as the secretion of inflammatory molecules. In endothelial cells (EC), MFG-E8 facilitates apoptosis. In addition, MFG-E8 has been found to be an essential component of the endothelial-derived microparticles that relay biosignals and modulate arterial wall phenotypes.

This review mainly focuses upon the landscape of MFG-E8 expression and signaling in adverse arterial remodeling. Recent discoveries have suggested that MFG-E8 associated interventions are novel approaches for the retardation of the enhanced rates of VSMC proliferation and EC apoptosis that accompany arterial wall inflammation and remodeling during aging and age-associated arterial disease.

Keywords: milk fat globule epidermal growth factor VIII, Arterial remodeling, Intervention

Introduction

Central arteries are composed of 3 layers: the tunica intima, the tunica media and the tunica adventitia. Over a lifespan, arterial endothelial cells (EC), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), as well as the elastin and collagen matrices in each layer are adversely remodeled via intimal-medial thickening, collagen deposition, and elastin fiber fragmentation [1–3]. Under varying pathophysiological conditions, adverse arterial remodeling facilitates endothelial dysfunction, intima cellularity, and monocyte infiltration [1–3]. These changes act as an impetus for the initiation and progression of vascular diseases such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, stroke, and arterial metabolic syndromes [1–4].

Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-8 (MFG-E8), also known as lactadherin or secreted epidermal growth factor repeat and discoidin domain containing protein-1 (SED1), was initially identified as a bridging molecule that released an “eat-me signal” between apoptotic cells and phagocytic macrophages [5–7]. Growing evidence has indicated that MFG-E8 is a secreted inflammatory mediator that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including vascular metabolic disorders and some tumors [8–12]. Recently, not only has MFG-E8 expression emerged as a molecular hallmark of adverse cardiovascular remodeling with aging [2, 3, 13, 14], but MFG-E8 signaling has also been found to mediate the vascular outcomes of cellular and matrix responses to the hostile stresses associated with hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis [15–19]. Increased MFG-E8 signaling promotes endothelial prothrombosis and triggers EC apoptosis, thus contributing to a disruption of the endothelium [20, 21], an enhancement of VSMC proliferation and invasion, as well as the deposition and amyloidization of the extracellular matrix [14, 21–31].

In this review, we focus on MFG-E8 expression and signaling during adverse arterial remodeling and explore the potential for MFG-E8-related interventions to be novel approaches for the retardation of the enhanced VSMC proliferation and EC apoptosis that accompanies arterial wall inflammation and, ultimately, to slow the adverse remodeling that accompanies age-associated arterial disease.

Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-8 (MFG-E8)

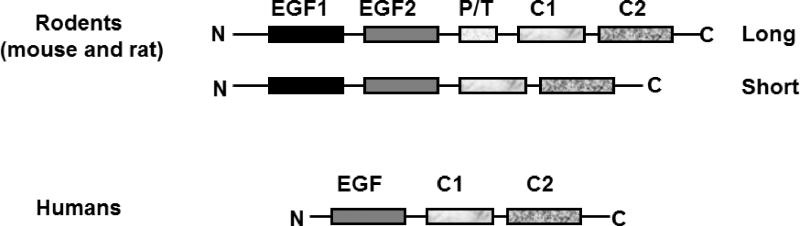

In 1990, a unique cDNA and its corresponding translated protein was identified and then sequenced in mouse mammary epithelial cells [32]. The gene was named as MFG-E8 since it is enriched in Milk Fat Globules and contains amino acid sequences similar to that of Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and blood clotting factor VIII [32]. The MFG-E8 gene is located on chromosome 1 in rats (RGD: 3083), chromosome 7 in mice (MGI: 102768), and chromosome 15 in humans (HGNC: 7036) [33, 34]. Due to pre-RNA alternative splicing, there is both a long and a short variant of the MFG-E8 mRNA expressed [33, 35, 36]. Figure 1 schematically illustrates MFG-E8’s protein structure: The N-terminal domain has 2 EGF-repeats, the second of which contains a conserved Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) integrin-binding cell adhesion motif. The C-terminal domain has 2 C domains homologous to the C1 and C2 domains found in blood-clotting factor V and VIII which usually bind to anionic phospholipids (phosphotydlserine/phosphatidylethanolamine, PS/PE) in a wide variety of cellular interactions. Although both splicing variants have been documented in rodents, only the short variant has been found in humans [33, 34, 37, 38]. The long variant contains an extra proline/threonine (P/T) rich domain between the second EGF-like repeat and the C1 domain [33, 37–39]. Furthermore, MFG-E8 is highly glycosylated in vivo, including both N- and O-glycosylation [38–41]. Notably, O-glycosylation only occurs on Thr residues of the long variant P/T rich domain and is critical for MFG-E8’s ability to deliver its “eat-me-signal.” The glycosylated region can easily bend, facilitating physical interactions between cellular debris and macrophages [41].

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the structure of MFG-E8. EGF: epidermal growth factor domain; C1 and C2: discoid domains or coagulation factor V or VIII-homologous domains. PT: proline/threonine-enrich motif.

In addition to interacting with extracellular phosphotydlserines or phosphatidylethanolamines, MFG-E8’s C terminus can also bind to collagen via its discoidin domains, homologous to those present in the collagen receptors DDR1 and DDR2, facilitating the turnover of the extracellular matrix, in particular, collagen [42].

Expression of MFG-E8 during arterial remodeling

Although MFG-E8 gene expression is abundant within smooth muscle cells (SMC) of the fetal aorta [43, 44], fetal SMC MFG-E8 mRNA levels markedly decrease after knocking out the platelet derived growth factor-isoform BB (PDGF-BB) gene [43]. It is well-known that PDGF-BB is not only a potent mitogen for VSMC, but also a key cellular chemoattractant in arterial restructuring [5], suggesting that MFG-E8 plays a crucial role in arterial remodeling. Indeed, MFG-E8 signaling is involved in both cardiovascular development and cardiovascular diseases (Table 1) [14, 15, 17–19, 23, 24, 26, 37, 43–52].

Table 1.

MFG-E8-related cardiovascular remodeling

| Classification | MFG-E8 expression | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular development | Increase/decrease | 43, 44, 47, 48 |

| Cardiovascular aging | Increase | 14, 23, 24, 46, 50, 51 |

| Hypertension | Increase | 14, 16 |

| Atherosclerosis | Increase/decrease | 15, 17 |

| Aneurysm/dissection | Increase/decrease | 26 |

| Arteritis | increase | 23, 24 |

| Diabetic vasculopathy | Increase | 18, 20, 21, 52 |

| Heart hypertrophy/heart failure | Increase | 19, 49 |

Aging

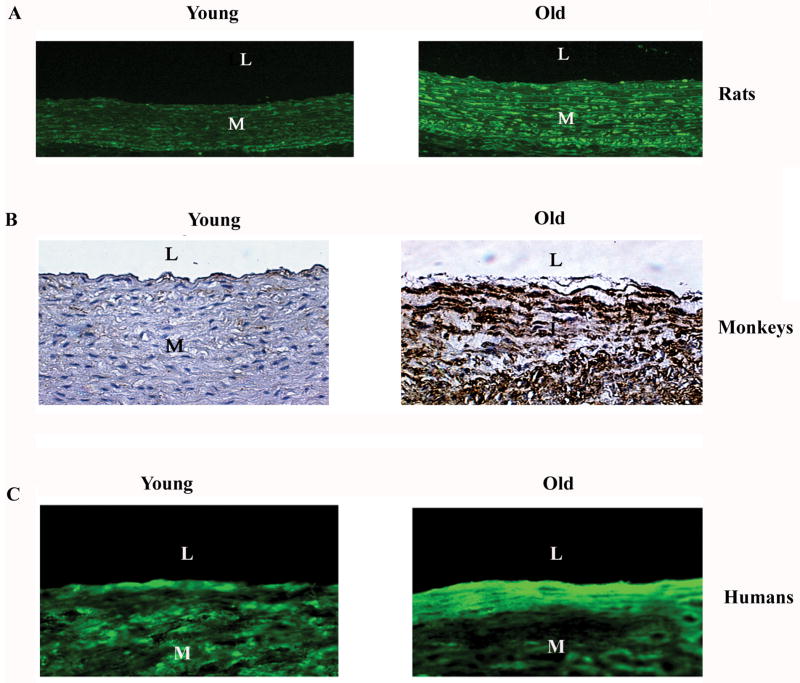

During aging, both MFG-E8 transcription and translation increase within the arterial walls and hearts of various species [14, 23, 24, 46]. MFG-E8 with or without glycosylation is markedly up-regulated in rat aortic walls with aging as well [Figure 2A] [14]. Importantly, increased levels of MFG-E8 are also present within both aged nonhuman primate and human arterial walls (Figure 2B and C) [14].

Figure 2.

MGF-E8 protein within the aortic wall in rats (A), monkeys (B), and humans (C). From Fu Z et al [14].

Vascular amyloidosis is markedly increased in the elderly [51]. Prior studies have shown that a 50 amino acid polypepetide called medin, derived from MFG-E8’s C2-like domain, not only tightly binds to tropoelastin but also eventually incorporates into arterial amyloids [23, 24 26, 28, 29]. These medin amyloids are commonly observed within arterial walls, including that of both the aorta and the temporal artery, in Caucasian populations over 50 years of age [23, 24, 26]. Recent study has shown that aortic medin amyloids serve as a trigger for amyloid A-derived amyloidosis [50].

In healthy humans, levels of serum MFG-E8 increase with advancing age and positively correlate with arterial pulse wave velocity (PWV), an index of arterial stiffness [52].

Atherosclerosis

High levels of MFG-E8 have been detected within endothelial cells, SMC, and macrophages of atherosclerotic aortae in both mice and humans [15, 17]. Interestingly, MFG-E8 is heterogeneously expressed and only detected in a subset of macrophages found in aortic atherosclerotic lesions [17]. Furthermore, in the advanced atherosclerotic plaques found in murine models, decreased macrophage MFG-E8 levels are associated with an inhibition of apoptotic cell engulfment, leading to the accumulation of cellular debris during the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [15].

Hypertension

Hypertension is a serious complication of renal disorders. It is noteworthy that MFG-E8 levels are dramatically increased in renal hypertensive aortic walls [16]. Furthermore, circulating MFG-E8 levels also increase within both hypertensive rats and patients with advanced kidney failure and are closely associated with increases in blood pressure, adverse matrix remodeling, and arterial stiffness (PWV) [16].

Diabetes mellitus

With advancing diabetic mellitus, macrovascular walls are adversely remodeled, leading to intimal-medial thickening and contributing to the development of cardiovascular complications; and retinal grow microvessels aberrantly, in part via the proliferation and migration of pericytes, resulting in an increase in neoangiogenesis and contributing to diabetic retinopathy [18, 53–55]. Recent studies have demonstrated that MFG-E8 is highly expressed within the proliferative aorta of rats with diabetes induced by streptozocin (STZ), a naturally occurring chemical particularly toxic to insulin-producing beta cells within the pancreas [18], and MFG-E8 has been involved in the pericytes-associated neoangiogenesis orchestrated by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling [53, 54]. Furthermore, circulating MPs mediated by MFG-E8 are closely associated with both microvascular and macrovascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus in humans [55]. Serum MFG-E8 levels positively correlate with levels of monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α1), and glycosylated hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) as well as 2 h postprandial blood glucose and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [52]. These findings suggest that an abundance of MFG-E8 is an important precipitating factor for the development of diabetic vascular complications.

Aneurysm/dissection

Arterial aneurysm/dissection is a complication of advanced stage hypertension and atherosclerosis. Interestingly, medin amyloid has been detected in specimens from patients afflicted by either thoracic aortic aneurysms or type A aortic dissection [26]. Surprisingly, medin amyloid deposition is significantly lower within aneurysm and dissection specimens compared with that of normal regions [26]. Focal medin immunoreactivity, however, is conspicuously found in the diseased media at sites of smooth muscle necrosis and degradation of matrix [26].

Arteritis

Medin amyloid deposits have been found in temporal artery biopsies from patients with histological signs of giant cell arteritis [24]. Immunoelectronic microscopy has indicated that these deposits appear to be topographically closely related to elastic fibers. Furthermore, fragmented elastic materials immunolabelled for medin are often found to be engulfed by giant cells (phagocytes) [24].

The diverse role of MFG-E8 within vascular cells

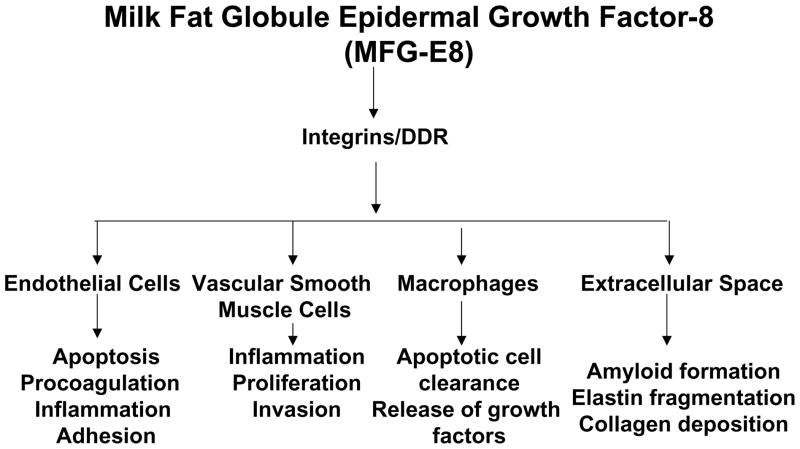

In vitro studies and network-based computer analyses show that a functional interdependence between MFG-E8 and other molecular components exists within arterial walls [14, 16, 56]. These findings suggest that MFG-E8 plays a diverse role in vascular cells and vascular inflammation (Figure 3) [14, 16, 56].

Figure 3.

Diagram of a diverse role for MFG-E8 in vascular cells.

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC)

MFG-E8 is not only abundantly expressed in fetal, aged, atherosclerotic and hypertrophied VSMC of arterial walls (Table 1), but is also one of most repressed genes in resting VSMC [27]. These findings suggest that MFG-E8 plays multiple roles in the VSMC stress response.

MFG-E8 is a secreted protein and an element of the angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced VSMC secretome [14, 57]. Chronic exposure of VSMC to intact MFG-E8 markedly increases MCP-1 activity [14] while chronic exposure of VSMC to medin fragments significantly increase secreted matrix metalloproteinase type-II (MMP-2) levels and cellular necrosis [26]. Furthermore, MFG-E8 mediates the Ang II/MCP-1/VSMC invasion signaling cascade [14]. Interestingly, both Ang II- and MFG-E8-associated increases in VSMC invasive capacity are substantially inhibited by either viral CC chemokine inhibitor (vCCI), an MCP-1 CC chemokine receptor 2 blocker, or MFG-E8 RNA interference [14].

Both recombinant human MFG-E8 (rhMFG-E8) treatment and an over-expression of full-length MFG-E8 via adenovirus infection not only elevates the levels of VSMC cell cycle accelerators such as phosphorylated-ERK1/2, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), and proliferating cellular nuclear antigen (PCNA), but also enhances bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation and proliferation [22]. Small RNA interference of MFG-E8 reduces the levels of PCNA and CDK4 expression in VSMC [22].

Endothelial cells

Endothelial integrity is a key to vascular health. However, both aging and metabolic disorders increase EC susceptibility to apoptosis, in part, due to increases in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) [58]. The overexpression of MFG-E8 induces EC apoptosis via an up-regulation of the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, cytochrome c release, and caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation [20, 21]. MFG-E8 silencing inhibits caspase-3 activity and reduces the phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β, thus lowering AGEs-induced EC apoptosis [20, 21].

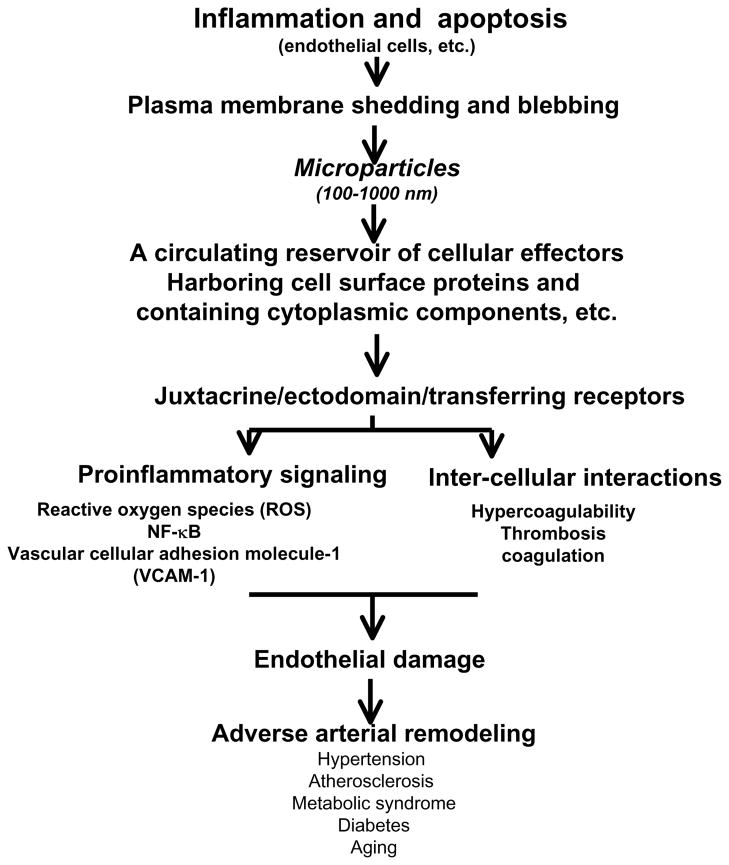

A growing body of evidence indicates that microparticles (MPs) derived from activated or apoptotic EC damages the endothelium. MPs are heterogeneous populations of vesicles with diameters ranging from 100 to 1000 nm that are released by plasma membrane budding from either activated or apoptotic cells [59–61]. Circulating MPs are significantly elevated in the elderly as well as in hypertensive, type I diabetic, and atherosclerotic patients [59, 60]. They play multiple roles in endothelial remodeling and display a broad spectrum of bioactive substances and receptors and harbor a concentrated set of cytokines, signaling proteins, mRNA, and microRNA, all of which contribute to proinflammatory signaling and cellular interactions in the pathogenesis of vascular disorders (Figure 4) [59–63].

Figure 4.

Diagram of multiple roles for microparticles in the arterial wall.

MPs promote the formation of platelet strings on the surface of EC via the MFG-E8/reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling axis, thus contributing to endothelial dysfunction [55, 62]. Interestingly, ECs can internalize MPs within a few hours through a process involving MFG-E8 and generate ROS via xanthine and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase [55]. This process promotes platelet/endothelial cell interactions under flow, contributing to vasculopathy [55]. Furthermore, MPs induce endothelial dysfunction by altering the balance of nitric monoxide (NO), ROS, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) inflammatory mediator production and release [63]. Recent studies have also shown that circulating MPs affect arterial remodeling and are involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE deficient mice on a high fat diet [64, 65].

Macrophages

MFG-E8 has been detected in a subset of macrophages within atherosclerotic lesions in situ [17]. In vitro studies show that the levels of MFG-E8 in macrophages isolated from the peritoneum of male LDR−/− mice fed a high fat diet decrease in comparison to that of cells from mice fed a low fat diet in response to cholesterol treatment [66]. MFG-E8 functions as an “eat-me bridge molecule” for macrophages that phagocytize apoptotic cells, alleviating inflammatory responses [15]. These studies suggest that an upregulation of MFG-E8 in macrophages enhances the clearance of apoptotic cellular debris known as a cellular efferocytosis and prevents the progression of atherosclerosis [15]. Other studies, however, show that MFG-E8 is markedly upregulated in advanced plaques and seems to promote the progression of atherosclerosis [17]. Further studies have shown that the macrophage secretome can activate VSMC via the liberation of depressed growth factor genes such as MFG-E8 [27]. Activated macrophages and VSMC synergistically release, MFG-E8, PDGF, transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF β1), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) [27, 67], and thus activating more VSMC and increasing their proliferation, migration and secretion in a paracrine or autocrine manner [14, 22, 27]. Macrophage-derived MFG-E8 also enhances the survival of unhealthy (moribund) EC [67]. Furthermore, MFG-E8 promotes the formation of endothelial neovascularization in a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-dependent manner, which plays an important role in the progression of advanced atherosclerotic plaques [68]. These findings suggest that macrophage MFG-E8 may also enhance the progression of atherosclerosis. Taken together, it is quite clear that MFG-E8 expression in macrophages has diverse roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and should be an area for further study.

Extracellular matrix

The vascular extracellular matrix (ECM) is essential for the structural integrity of arterial walls and serves as a platform for the binding and retention of infiltrated circulating and secreted vascular cell molecules that are key components of intercellular communication within the arterial wall. The DDR-like sequence within the discoidin domain of MFG-E8 is not only able to bind to collagen, but also contributes to its turnover in the extracellular matrix [28–31, 42, 69]. Immunostaining and proteomics analyses have also demonstrated that MFG-E8 is a secreted extracellular adhesive molecule within both the aortic extracellular space and aortic valves [28–31]. An abundance of MFG-E8 in aortic valves is related to local stimulus responses, including mechanical stress and blood flow turbulence, which may play an important role in the initiation and progression of congenital and acquired valve diseases [30].

Furthermore, the MFG-E8-derived medin is co-localized with elastic fibers of older arteries [28, 29]. Medin binds to tropoelastin in a concentration-dependent fashion and forms amyloid-like fibrils within the extracellular space of arterial walls [28, 29]. It has also been found in the β-sheets of amyloid proteins [70], suggesting that MFG-E8 fragments may play an amyloidogenic role in aged arterial walls.

Interventions of MFG-E8 signaling

Indirect interventions

Anti-hypertensive drugs

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, enalapril, is commonly prescribed for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure. Interestingly, the administration of enalapril to hypertensive rats markedly decreases MFG-E8 deposition within the aorta while simultaneously reducing PWV, an index of arterial stiffness [16]. Furthermore, β-receptor blockers are also commonly prescribed for treatment of hypertension and heart failure. Exposure of VSMC to Carvedilol, a β-receptor blocker, suppresses MFG-E8 expression, and maintains VSMC quiescence [25].

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors

The incidence of hyperlipidemia markedly increases within the elderly with or without disorders such as obesity, hypertension and atherosclerosis [71, 72]. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are widely prescribed and have been shown to effectively reduce the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular disease [73]. As mentioned before, circulating MPs mediated by MFG-E8 have been associated with endothelial dysfunction [74–77]. Fluvastatin treatment substantially reduces circulating MPs, and consequently improve endothelial function, which may be associated with an inhibition of MFG-E8 signaling [78]. Details regarding the statins/MFG-E8 signaling axis are still unknown and thus, require further study.

Anti-platelet drugs

The incidence of thrombosis is increased in the elderly with or without vascular disorders [79]. The thienopyridine P2Y12 antagonists clopidogrel and prasugrel substantially suppress endothelial and platelet-derived MPs and prevent cardiovascular events [80]. These salutary roles may result from a blockade of MFG-E8 signaling, which need to be further clarified.

Anti-diabetic drugs

It is known that glibenclamide, a sulfonylurea, can be used to treat diabetes type 2 via plasma glucose level control. It is known that both insulin and glucose increase MFG-E8 production from adipocytes [81]. However, whether those effects are directly mediated by MFG-E8 signaling is unknown and need to be addressed in the future.

Natural polyphenols

Resveratrol or grape-seeds proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE) procyanidine is part of a complex family of polyphenol polymers that are widespread in nature, and are present within many processed products such as grape wines, few fruits, and vegetables. GSPE and Resveratrol significantly reduce MFG-E8 expression in EC induced by AGEs [18]. Moreover, treatment of EC with both GSPE and Resveratrol significantly inhibits EC apoptosis induced by AGEs via a down-regulation of MFG-E8 signaling [20, 21].

Direct interventions

Silencing MFG-E8 substantially inhibits not only VSMC proliferation and invasion but also EC apoptosis [14, 20, and 21]. In addition, Angiolix (HuMc3), a humanized monoclonal antibody against MFG-E8/lactadherin, has considerable potential for treating cancer, particularly breast and ovarian cancers [82]. Whether Angiolix effects cardiovascular remodeling, however, remain unknown.

Concluding remarks

MFG-E8 signaling is an element of the inflammation network in cardiovascular development and pathophysiology. This hybrid protein plays a diverse role in vascular endothelial cells, SMC, macrophages, and matrix remodeling. The up-regulation of MFG-E8 and its derived medin are closely associated with adverse arterial remodeling in aging, hypertension, aneurism/dissection, arteritis, and diabetes. Down-regulation of MFG-E8 signaling reduces endothelial cell apoptosis, and SMC proliferation/invasion in vitro. Furthermore, a blockade of MFG-E8 signaling in vivo is closely linked to the alleviation of hypertensive-and metabolic-associated adverse arterial restructuring. Taken together, targeting MFG-E8 has the potential to become a novel strategy to combat age-associated arterial metabolic disorders and may merit further development.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank Robert E. Monticone for his assistance in preparing this document.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Lakatta EG, Wang M, Najjar SS. Arterial aging and subclinical arterial disease are fundamentally intertwined at macroscopic and molecular levels. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:583–604. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: a journey into subclinical arterial disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:201–207. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283361c0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M, Khazan B, Lakatta E. G Central arterial aging and angiotensin II signaling. Current Hypertension Reviews. 2010;6:266–281. doi: 10.2174/157340210793611668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Muller DC, Andres R, Hougaku H, Metter EJ, Lakatta EG. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Apr 21;43(8):1388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida H, Kawane K, Koike M, Mori Y, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Phosphatidylserine-dependent engulfment by macrophages of nuclei from erythroid precursor cells. Nature. 2005;437:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature03964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miyasaka K, Aozasa K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Autoimmune disease and impaired uptake of apoptotic cells in MFG-E8-deficient mice. Science. 2004;304:1147–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1094359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature. 2002;417:182–187. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raymond A, Ensslin MA, Shur BD. SED1/MFG-E8: a bi-motif protein that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:957–966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jinushi M, Nakazaki Y, Carrasco DR, Draganov D, Souders N, Johnson M, Mihm MC, Dranoff G. Milk fat globule EGF-8 promotes melanoma progression through coordinated Akt and twist signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8889–8898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor MR, Couto JR, Scallan CD, Ceriani RL, Peterson JA. Lactadherin (formerly BA46), a membrane-associated glycoprotein expressed in human milk and breast carcinomas, promotes Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-dependent cell adhesion. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:861–869. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tahara Hideaki, Sato Marimo, Thurin Magdalena, Wang Ena, Butterfield Lisa H, Disis Mary L, Fox Bernard A, Lee Peter P, Khleif Samir N, Wigginton Jon M, Ambs Stefan, Akutsu Yasunori, Chaussabel Damien, Doki Yuichiro, Eremin Oleg, Fridman Wolf Hervé, Hirohashi Yoshihiko, Imai Kohzoh, Jacobson James, Jinushi Masahisa, Kanamoto Akira, Kashani-Sabet Mohammed, Kato Kazunori, Kawakami Yutaka, Kirkwood John M, Kleen Thomas O, Lehmann Paul V, Liotta Lance, Lotze Michael T, Maio Michele, Malyguine Anatoli, Masucci Giuseppe, Matsubara Hisahiro, Mayrand-Chung Shawmarie, Nakamura Kiminori, Nishikawa Hiroyoshi, Palucka A Karolina, Petricoin Emanuel F, Pos Zoltan, Ribas Antoni, Rivoltini Licia, Sato Noriyuki, Shiku Hiroshi, Slingluff Craig L, Streicher Howard, Stroncek David F, Takeuchi Hiroya, Toyota Minoru, Wada Hisashi, Wu Xifeng, Wulfkuhle Julia, Yaguchi Tomonori, Zeskind Benjamin, Zhao Yingdong, Zocca Mai-Britt, Marincola Francesco M. Emerging concepts in biomarker discovery; The US-Japan workshop on immunological molecular markers in oncology. J Transl Med. 2009;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neutzner M, Lopez T, Feng X, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Udey MC. MFG-E8/lactadherin promotes tumor growth in an angiogenesis-dependent transgenic mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6777–6785. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz A, Massy ZA, Fliser D, Lindholm B, Wiecek A, Martínez-Castelao A, Covic A, Goldsmith D, Süleymanlar G, London GM, Zoccali C. Clinical usefulness of novelprognostic biomarkers in patients on hemodialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011 Nov 1; doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Z, Wang M, Gucek M, Zhang J, Wu J, Jiang L, Monticone RE, Khazan B, Telljohann R, Mattison J, Sheng S, Cole RN, Spinetti G, Pintus G, Liu L, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Spurgeon H, Ingram DK, Everett AD, Lakatta EG, Van Eyk JE. Milk fat globule protein epidermal growth factor-8: a pivotal relay element within the angiotensin II and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signaling cascade mediating vascular smooth muscle cell invasion. Circ Res. 2009;104:1337–1346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ait-Oufella H, Kinugawa K, Zoll J, Simon T, Boddaert J, Heeneman S, Blanc-Brude O, Barateau V, Potteaux S, Merval R, Esposito B, Teissier E, Daemen MJ, Lesèche G, Boulanger C, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Lactadherin deficiency leads to apoptotic cell accumulation and accelerated atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2168–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin YP, Hsu ME, Chiou YY, Hsu HY, Tsai HC, Peng YJ, Lu CY, Pan CY, Yu WC, Chen CH, Chi CW, Lin CH. Comparative proteomic analysis of rat aorta in a subtotal nephrectomy model. Proteomics. 2010;10:2429–2443. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagnato C, Thumar J, Mayya V, Hwang SI, Zebroski H, Claffey KP, Haudenschild C, Eng JK, Lundgren DH, Han DK. Proteomics analysis of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque: a feasibility study of direct tissue proteomics by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1088–1102. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XL, Li BY, Gao HQ, Cheng M, Xu L, Li XH, Zhang WD, Hu JW. Proteomics approach to study the mechanism of action of grape seed proanthocyanidin extracts on arterial remodeling in diabetic rats. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25:237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strøm CC, Kruhøffer M, Knudsen S, Stensgaard-Hansen F, Jonassen TE, Orntoft TF, Haunsø S, Sheikh SP. Identification of a core set of genes that signifies pathways underlying cardiac hypertrophy. Comp Funct Genomics. 2004;5:459–470. doi: 10.1002/cfg.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li BY, Li XL, Gao HQ, Zhang JH, Cai Q, Cheng M, Lu M. Grape seed procyanidin B2 inhibits advanced glycation end products induced endothelial cell apoptosis through regulating GSK3β phosphorylation. Cell Biol Int. 35:663–669. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li BY, Li XL, Cai Q, Gao HQ, Cheng M, Zhang JH, Wang JF, Yu F, Zhou RH. Induction of lactadherin mediates the apoptosis of endothelial cells in response to advanced glycation end products and protective effects of grape seed procyanidin B2 and resveratrol. Apoptosis. 2011;16:732–745. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0602-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M, Fu Z, Zhang J, Wu J, Jiang L, Khazan B, Telljohann R, Krug A, Monticone R, Van Eyk J, Lakatta E. Milk Fat Globule-EGF-Factor 8 (MFG-E8): A Novel Protein Orchestrator of Inflammatory Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Invasion. Circ Res. 2009;105:e55–e62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng S, Glennert J, Westermark P. Medin-amyloid: a recently characterized age-associated arterial amyloid form affects mainly arteries in the upper part of the body. Amyloid. 2005;12:96–102. doi: 10.1080/13506120500107006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng S, Westermark GT, Näslund J, Häggqvist B, Glennert J, Westermark P. Medin and medin-amyloid in ageing inflamed and non-inflamed temporal arteries. J Pathol. 2002;196:91–96. doi: 10.1002/path.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M, Wang X, Ching CB, Chen WN. Proteomic profiling of cellular responses to Carvedilol enantiomers in vascular smooth muscle cells by iTRAQ-coupled 2-D LC-MS/MS. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1601–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng S, Larsson A, Wassberg E, Gerwins P, Thelin S, Fu X, Westermark P. Role of aggregated medin in the pathogenesis of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1195–205. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beauchamp NJ, van Achterberg TA, Engelse MA, Pannekoek H, de Vries CJ. Gene expression profiling of resting and activated vascular smooth muscle cells by serial analysis of gene expression and clustering analysis. Genomics. 2003;82:288–299. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson A, Peng S, Persson H, Rosenbloom J, Abrams WR, Wassberg E, Thelin S, Sletten K, Gerwins P, Westermark P. Lactadherin binds to elastin--a starting point for medin amyloid formation? Amyloid. 2006;13:78–85. doi: 10.1080/13506120600722530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Häggqvist B, Näslund J, Sletten K, Westermark GT, Mucchiano G, Tjernberg LO, Nordstedt C, Engström U, Westermark P. Medin: an integral fragment of aortic smooth muscle cell-produced lactadherin forms the most common human amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8669–8674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angel PM, Nusinow D, Brown CB, Violette K, Barnett JV, Zhang B, Baldwin HS, Caprioli RM. Networked-based Characterization of Extracellular Matrix Proteins from Adult Mouse Pulmonary and Aortic Valves. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:812–823. doi: 10.1021/pr1009806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Didangelos A, Yin X, Mandal K, Baumert M, Jahangiri M, Mayr M. Proteomics characterization of extracellular space components in the human aorta. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2048–2062. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stubbs JD, Lekutis C, Singer KL, Bui A, Yuzuki D, Srinivasan U, Parry G. cDNA cloning of a mouse mammary epithelial cell surface protein reveals the existence of epidermal growth factor-like domains linked to factor VIII-like sequences. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1990;87:8417–8421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess BL, Abrams TA, Nagata S, Hall MO. MFG-E8 in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium of rat and mouse. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1437–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins C, Nehlin JO, Stubbs JD, Kowbel D, Kuo WL, Parry G. Mapping of a newly discovered human gene homologous to the apoptosis associated-murine mammary protein, MFG-E8, to chromosome 15q25. Genomics. 1997;39:117–118. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cebo C, Caillat H, Bouvier F, Martin P. Major proteins of the goat milk fat globule membrane. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:868–876. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charlwood J, Hanrahan S, Tyldesley R, Langridge J, Dwek M, Camilleri P. Use of proteomic methodology for the characterization of human milk fat globular membrane proteins. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:314–324. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe T, Totsuka R, Miyatani S, Kurata S, Sato S, Katoh I, Kobayashi S, Ikawa Y. Production of the long and short forms of MFG-E8 by epidermal keratinocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;321:185–193. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1148-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mather IH. A review and proposed nomenclature for major proteins of the milk-fat globule membrane. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83:203–247. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74870-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oshima K, Aoki N, Negi M, Kishi M, Kitajima K, Matsuda T. Lactation-dependent expression of an mRNA splice variant with an exon for a multiply O-glycosylated domain of mouse milk fat globule glycoprotein MFG-E8. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:522–528. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aoki N, Ujita M, Kuroda H, Urabe M, Noda A, Adachil T, Nakamura R, Matsuda T. Immunologically cross-reactive 57 kDa and 53 kDa glycoprotein antigens of bovine milk fat globule membrane: isoforms with different N-linked sugar chains and differential glycosylation at early stages of lactation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;6(1200):227–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oshima K, Aoki N, Kato T, Kitajima K, Matsuda T. Secretion of a peripheral membrane protein, MFG-E8, as a complex with membrane vesicles. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1209–1218. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atabai K, Jame S, Azhar N, Kuo A, Lam M, McKleroy W, Dehart G, Rahman S, Xia DD, Melton AC, Wolters P, Emson CL, Turner SM, Werb Z, Sheppard D. Mfge8 diminishes the severity of tissue fibrosis in mice by binding and targeting collagen for uptake by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3713–3722. doi: 10.1172/JCI40053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bondjers C, Kalén M, Hellström M, Scheidl SJ, Abramsson A, Renner O, Lindahl P, Cho H, Kehrl J, Betsholtz C. Transcription profiling of platelet-derived growth factor-B-deficient mouse embryos identifies RGS5 as a novel marker for pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:721–729. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheidl SJ, Nilsson S, Kalén M, Hellström M, Takemoto M, Håkansson J, Lindahl P. mRNA expression profiling of laser microbeam microdissected cells from slender embryonic structures. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:801–813. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Millette E, Rauch BH, Kenagy RD, Daum G, Clowes AW. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB transactivates the fibroblast growth factor receptor to induce proliferation in human smooth muscle cells. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant Jennifer E, Bradshaw Amy D, Schwacke John H, Baicu Catalin F, Zile Michael R, Schey Kevin L. Quantification of Protein Expression Changes in the Aging Left Ventricle of Rattus norvegicus. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4252–4263. doi: 10.1021/pr900297f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu LY, Ciliate C. Characterizing the role of the NELL1 gene in cardiovascular development. US Department of Energy Journal of Undergraduate Research. :63–70. www.scied.science.doe.gov/.../Characterizing%20Role%20of%20NELL1.pdf.

- 48.Faustino RS, Behfar A, Perez-Terzic C, Terzic A. Genomic chart guiding embryonic stem cell cardiopoiesis. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfrang J, Fraccarollo D, Ertl G, Bauersachs J1, Schäfer A. ACE inhibition reduces monocyte MFG-E8 and MCP-1 expression associated with increased serum fractalkine levels in rats with chronic heart failure. www.gth2009.org/fileadmin/template/abstracts/PP5.5-2.pdf.

- 50.Larsson A, Malmström S, Westermark P. Signs of cross-seeding: aortic medin amyloid as a trigger for protein AA deposition. Amyloid. 2011;18:229–234. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.630761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cornwell GG, 3rd, Westermark P, Murdoch W, Pitkänen P. Senile aortic amyloid. A third distinctive type of age-related cardiovascular amyloid. Am J Pathol. 1982;108:135–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng M, Li BY, Li XL, Wang Q, Zhang JH, Jing XJ, Gao HQ. Correlation between serum lactadherin and pulse wave velocity and cardiovascular risk factors in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011 Oct 19; doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.09.030. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Motegi S, Leitner WW, Lu M, Tada Y, Sárdy M, Wu C, Chavakis T, Udey MC. Pericyte-derived MFG-E8 regulates pathologic angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2024–2034. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Motegi S, Garfield S, Feng X, Sárdy M, Udey MC. Potentiation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β signaling mediated by integrin-associated MFG-E8. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2653–2664. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.233619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terrisse AD, Puech N, Allart S, Gourdy P, Xuereb JM, Payrastre B, Sié P. Internalization of microparticles by endothelial cells promotes platelet/endothelial cell interaction under flow. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2810–2819. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang M, Spinetti G, Monticone RE, Zhang J, Wu J, Jiang L, Khazan B, Telljohann R, Lakatta EG. A local proinflammatory signalling loop facilitates adverse age-associated arterial remodeling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao BB, Stuart L, Feener EP. Label-free quantitative analysis of one-dimensional PAGE LC/MS/MS proteome: application on angiotensin II-stimulated smooth muscle cells secretome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2399–2409. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800104-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin L, Park S, Lakatta EG. RAGE signaling in inflammation and arterial aging. Front Biosci. 2009 Jan 1;14:1403–13. doi: 10.2741/3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mause SF, Weber C. Microparticles: protagonists of a novel communication network for intercellular information exchange. Circ Res. 2010;107:1047–1057. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forest A, Pautas E, Ray P, Bonnet D, Verny M, Amabile N, Boulanger C, Riou B, Tedgui A, Mallat Z, Boddaert J. Circulating microparticles and procoagulant activity in elderly patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:414–420. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quesenberry PJ, Aliotta JM. Cellular phenotype switching and microvesicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peterson DB, Sander T, Kaul S, Wakim BT, Halligan B, Twigger S, Pritchard KA, Jr, Oldham KT, Ou JS. Comparative proteomic analysis of PAI-1 and TNF-alpha-derived endothelial microparticles. Proteomics. 2008;8:2430–2446. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rautou PE, Leroyer AS, Ramkhelawon B, Devue C, Duflaut D, Vion AC, Nalbone G, Castier Y, Leseche G, Lehoux S, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles from human atherosclerotic plaques promote endothelial ICAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration. Circ Res. 2011;108:335–343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chironi GN, Simon A, Boulanger CM, Dignat-George F, Hugel B, Megnien JL, Lefort M, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Circulating microparticles may influence early carotid artery remodeling. J Hypertens. 2010;28:789–796. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d0a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baron M, Leroyer AS, Majd Z, Lalloyer F, Vallez E, Bantubungi K, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Delerive P, Boulanger GM, Staels B, Tailleux A. PPARα activation differently affects microparticle content in atherosclerotic lesions and liver of a mouse model of atherosclerosis and NASH. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Becker L, Gharib SA, Irwin AD, Wijsman E, Vaisar T, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. A macrophage sterol-responsive network linked to atherogenesis. Cell Metab. 2010;11:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selvarajan K. Adherent and nonadherent macrophages in cell survival and death. Dissertation. 2009 td.ohiolink.edu/send-pdf.cgi/Selvarajan%20Krithika.pdf?osu1257884236.

- 68.Silvestre JS, Théry C, Hamard G, Boddaert J, Aguilar B, Delcayre A, Houbron C, Tamarat R, Blanc-Brude O, Heeneman S, Clergue M, Duriez M, Merval R, Lévy B, Tedgui A, Amigorena S, Mallat Z. Lactadherin promotes VEGF-dependent neovascularization. Nat Med. 2005;11:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogel W. Discoidin domain receptors: structural relations and functional implications. FASEB J. 1999;13 (Suppl):S77–S82. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tzotzos S, Doig AJ. Amyloidogenic sequences in native protein structures. Protein Sci. 2010;19:327–348. doi: 10.1002/pro.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Morrell CH, Lakatta EG Cardiovascular Health Study. The metabolic syndrome in older individuals: prevalence and prediction of cardiovascular events: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:882–887. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru’ M, Albai G, Strait J, Tarasov KV, Piras MG, Cao A, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Lakatta EG. Age- and gender-specific awareness, treatment, and control of cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical vascular lesions in a founder population: the SardiNIA Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Freyssinet JM. Cellular microparticles: what are they bad or good for? J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1655–1662. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simpson RJ, Jensen SS, Lim JW. Proteomic profiling of exosomes: current perspectives. Proteomics. 2008;8:4083–4099. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Tedgui A. Circulating microparticles: a potential prognostic marker for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Hypertension. 2006;48:180–186. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231507.00962.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rautou PE, Vion AC, Amabile N, Chironi G, Simon A, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles, vascular function, and atherothrombosis. Circ Res. 2011;109:593–606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tramontano AF, O’Leary J, Black AD, Muniyappa R, Cutaia MV, El-Sherif N. Statin decreases endothelial microparticle release from human coronary artery endothelial cells: implication for the Rho-kinase pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Virmani R, Avolio AP, Mergner WJ, Robinowitz M, Herderick EE, Cornhill JF, Guo SY, Liu TH, Ou DY, O’Rourke M. Effect of aging on aortic morphology in populations with high and low prevalence of hypertension and atherosclerosis. Comparison between occidental and Chinese communities. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:1119–1129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Judge HM, Buckland RJ, Sugidachi A, Jakubowski JA, Storey RF. Relationship between degree of P2Y12 receptor blockade and inhibition of P2Y12-mediated platelet function. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1210–1217. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aoki N, Jin-no S, Nakagawa Y, Asai N, Arakawa E, Tamura N, Tamura T, Matsuda T. Identification and characterization of microvesicles secreted by 3T3-L1 dipocytes: redox- and hormone-dependent induction of milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor 8-associated microvesicles. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3850–3862. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deonarain MP, Kousparou CA, Epenetos AA. Antibodies targeting cancer stem cells: A new paradigm in immunotherapy? MAbs. 2009;1:12–25. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.1.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]