Abstract

Background

Patients with normal (mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≤20 mmHg) and borderline mean pulmonary pressures (mPAP) (boPAP; 21–24 mmHg) are “at risk” of developing pulmonary hypertension(PH). The objectives of this analysis were 1)to examine the baseline characteristics in systemic sclerosis(SSc) with Normal and boPAP, and 2) to explore long term outcomes in SSc patients with boPAP vs. Normal hemodynamics.

Methods

PHAROS is a multicenter prospective longitudinal cohort of patients with SSc “at risk” or recently diagnosed with resting PH on right heart catheterization (RHC). Baseline clinical characteristics, pulmonary function tests, high resolution computed tomography(HRCT), 2-D echocardiogram, and RHC results were analyzed in Normal and boPAP groups.

Results

A total of 206 patients underwent RHC (35 Normal, 28 boPAP, 143 had resting PH). There were no differences in the baseline demographics. Patients in the boPAP group were more likely to have restrictive lung disease (67% vs. 30%), fibrosis on HRCT and a higher estimated right ventricular systolic pressure on echocardiogram (46.3 vs. 36.2mmHg; p<0.05) than patients with Normal hemodynamics. RHC revealed higher pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and more elevated mPAP on exercise(mPAP ≥30; 88% vs. 56%) in the boPAP group(p<0.05 for both). Patients were followed for a mean of 25.7 months and 24 patients had a repeat RHC during this period. During follow up, 55% of the boPAP group and 32% of the Normal group developed resting PH (p=NS).

Conclusions

Patients with boPAP have a greater prevalence of abnormal lung physiology, pulmonary fibrosis and presence of exercise mPAP ≥30mmHg.

Keywords: Pulmonary hypertension, Systemic sclerosis, Borderline, Pulmonary hemodynamics

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) are the leading causes of mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc)[1]. The recently concluded 4th World Symposium on PH reclassified patients with resting mPAP ≤20 mmHg as “normal pulmonary hemodynamics” and 21–24 mmHg as “borderline” group [2] on right heart catheterization (RHC). This distinction was based on a systematic review of 47 studies that measured resting mPAP of healthy volunteers. In this review, the normal mean (SD) resting mPAP was 14 (3.3) mmHg and the upper limit of normal was 20.6mmHg[3]. Although it is well established that resting PH (mPAP≥25) in SSc is associated with poor prognosis[1, 4–6], data regarding the natural history and outcomes in patients with normal hemodynamics and borderline mPAPs (boPAP) are lacking[7, 8].

The Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS) is a prospective longitudinal study that includes patients with SSc “at risk” for developing PH and those who have newly diagnosed resting PH. The study is being conducted in the US with a goal of discovering risk factors for PH and defining the course of disease progression in patients with established pulmonary vascular disease. The objectives of this analysis were to examine 1) the baseline demographics and clinical features in patients with SSc with Normal resting hemodynamics (mPAP ≤20mmHg) vs. boPAP, and 2) to explore long term outcomes in SSc patients with Normal vs. boPAP resting hemodynamics.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

PHAROS[9] is a multicenter study enrolling SSc patients who met the ACR classification criteria for definite SSc[10] or the LeRoy definition[11] of limited cutaneous or diffuse cutaneous SSc[9]. The study was approved by the review board at each institution and each patient signed the voluntary consent form before participating in the study. PHAROS included two patient groups. The first group was patients “at-risk” for developing pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Entry criteria for patients “at-risk” for PH were any one of the following three criteria:

Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO)<55% predicted without severe interstitial lung disease (ILD) (defined as FVC<65% predicted and/or a thoracic high resolution CT scan of the lungs with moderate to severe ILD,); or

Forced vital capacity(FVC) % / DLCO % ratio ≥1.6; or

Estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) >35mmHg on echocardiogram with Doppler.

The second patient group was resting PH patients enrolled within 6 months of RHC. Patients with resting PH were excluded if left ventricular ejection fraction(LVEF) was less than 50% or the PH was non-SSc related. Exercise RHC was performed per local institutional protocols[12, 13]. No patients were enrolled based on exercise RHC data alone.

Resting PH was divided into three groups: Group 1(PAH) was defined as a mPAP ≥25mmHg with a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤ 15mmHg on RHC, with no significant pulmonary interstitial fibrosis (FVC ≥65% predicted and none-to-mild ILD on HRCT); Group 2 (pulmonary venous hypertension; PVH) was defined as an mPAP≥25mmHg with a PCWP > 15mmHg on RHC; and Group 3 (PH-ILD) was defined as an mPAP≥25mmHg on RHC, PCWP ≤15mmHg and significant ILD (FVC < 65% predicted and/or moderate to severe ILD on HRCT). Patients with no resting PH were further divided as “Normal pulmonary hemodynamics (mPAP< 20 mmHg)” and “boPAP” (mPAP = 21–24 mmHg).

The baseline demographics collected at time of enrollment included clinical history, SSc subtype, disease duration from first non-Raynaud’s symptom, medications, and smoking history. Autoantibodies were measured at the local laboratory. The patients completed questionnaires including the Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire, the University of California at San Diego Dyspnea Index, and the SF-36 at baseline. Patients also had baseline physician evaluation and included modified Rodnan skin score. PFTs, echocardiograms, HRCT and 6 minute walk test was encouraged in all patients and completed in the majority of patients. HRCT fibrosis was graded as normal (no fibrosis), mild, moderate or severe fibrosis by the local radiologist. The RHCs were performed based on the clinical judgment of the treating physician. Medical history, hospitalizations, medication information and outcome events were recorded, and individual investigators independently initiated PAH-specific therapy when indicated.

All data were collected using paper case report forms and manually entered into a central computerized database. For quality control, the authors contacted sites to confirm any outlying data values.

Statistical analysis

We compared patients with Normal vs. boPAP groups using the two-sample t-test for normally-distributed continuous data, Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-parametric continuous data, and chi-square test for categorical data. Since the focus of the manuscript is to compare boPAP vs. Normal groups, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was done. The survival rates of the two groups were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model. The proportionality assumption was tested by introducing the interaction of log-time and the independent variable group as a time-varying covariate. Analyses were performed using STATA 10.

RESULTS

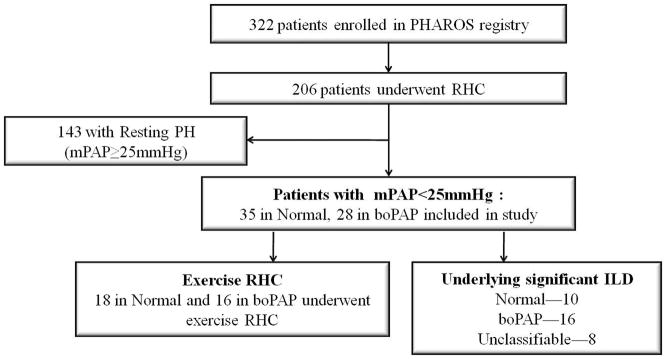

The PHAROS registry enrolled 322 patients from July 2005 to April 2010, of whom 206 patients underwent hemodynamic assessment; 177 RHCs were performed during the initial visit and 31 were performed during follow-up visits. Of these RHCs, 143 had resting PH (mPAP≥25), 35 (56%) had Normal pulmonary hemodynamics (mPAP≤ 20 mmHg) and 28 (44%) had boPAP (mPAP 21-24 mmHg) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients during initial RHC in the PHAROS registry

RHC-right heart catheterization; PH-pulmonary hypertension; boPAP-borderline mPAP (mPAP 21-24mmHg)

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WHOLE GROUP

The average age for the whole group was 57.2 years, mean (SD) disease duration from onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon was 11.6 (10.3) years, 85% were women, and 60% had limited cutaneous SSc. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographics of Normal vs. boPAP groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Normal vs. BoPAP vs. Resting PH groups who underwent RHC

| TOTAL(N=206) | NORMAL(N=35) | BORDERLINE (N=28) | Resting PH (N=143) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | |

| Age, years | 57.2(11.6) | 58.0 | 55.7(12.6) | 57.0 | 54.8 (10.4) | 55.0 | 58.0(11.5) | 59.0 |

| Female, N(%) | 171(85.1) | 28(80.0) | 24(85.7) | 119(85.6) | ||||

| Scleroderma subtype, N(%) | ||||||||

| Limited | 129(62.6) | 22(62.9) | 16(61.5) | 91(62.8) | ||||

| Diffuse | 66(32.0) | 11(29.7) | 9(34.6) | 46(31.7) | ||||

| Unclassified | 11(5.3) | 2(5.4) | 1(3.9) | 6(5.5) | ||||

| Disease Duration (yrs) | ||||||||

| From onset of Raynaud phenomenon | 11.6(10.3) | 8.5 | 10.7(8.5) | 7.8 | 8.6(6.1) | 7.3 | 12.4(11.2) | 9.0 |

| From onset of non-Raynaud symptom | 8.7(7.3) | 6.7 | 7.8(5.4) | 6.8 | 8.1(6.0) | 6.2 | 9.1(8.0) | 6.7 |

| From first SSc diagnosis | 7.1 (8.1) | 4.5 | 5.1(4.5) | 3.6 | 5.9(6.2) | 3.3 | 7.8(9.0) | 5.3 |

| Race, N(%) | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 140(69.6) | 22(62.9) | 17(60.7) | 101(73.2) | ||||

| Hispanic | 15(7.5) | 5(14.3) | 2(7.1) | 8(5.8) | ||||

| African-American | 37(18.4) | 6(17.1) | 7(25.0) | 24(17.4) | ||||

| Other | 9(4.5) | 2(5.7) | 2(7.1) | 5(3.6) | ||||

| HAQ-DI score(0–3) | 0.9(0.8) | 0.8 | 0.8(0.8) | 0.5 | 0.7(0.6) | 0.6 | 1.0(0.8) | 1.0 |

| VAS Breathing score(0–3) | 1.2(0.9) | 1.0 | 0.8(0.7) | 0.6 | 0.9(0.9) | 0.5 | 1.3(0.9) | 1.5 |

| VAS Raynaud’s score(0–3) | 0.6(0.8) | 0.3 | 0.6(0.7) | 0.4 | 0.4(0.7) | 0.1 | 0.7(0.8) | 0.3 |

| VAS Finger ulcers score(0–3) | 0.5(0.8) | 0.1 | 0.4(0.7) | 0.1 | 0.3(0.6) | 0 | 0.5(0.8) | 0.1 |

| VAS Overall score(0–3) | 1.2(0.8) | 1.2 | 1.0(0.8) | 1.0 | 0.9(0.8) | 0.8 | 1.4(0.8) | 1.4 |

| UCSD score(0–5) | 1.6(1.1) | 1.5 | 1.2(0.8) | 1.2 | 1.4(1.1) | 1.1 | 1.8(1.2) | 1.7 |

| SF-36 PCS | 30.7(10.8) | 28.4 | 33.6(9.6) | 31.1 | 36.8(13.2) | 37.9 | 28.5(9.9) | 27.5 |

| SF-36 MCS | 48.1(11.3) | 49.6 | 49.6(12.8) | 54.0 | 50.3(9.4) | 49.9 | 47.2(11.2) | 49.0 |

p> 0.05 for all comparisons; HAQ-DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire – Disease Index; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale, UCSD: University of California at San Diego; SF-36: Short form 36; PCS: Physical Component Summery; MCS: Mental Component Summery

At baseline, patients with resting PH had numerically higher (worse) symptoms compared to the Normal or boPAP group measured by both HRQOL and dyspnea instruments (HAQ-DI, VAS breathing, VAS overall health, UCSD dyspnea, and SF-36 PCS) (Table 1) and by NYHA classification (Table 2). No difference in disease duration, MRSS, autoantibody profile, or degree of fibrosis on HRCT was detected between resting PH versus Normal or boPAP. However the resting PH group had numerically worse DLCO % predicted, 6 minute walk test and higher RVSP on 2-D echocardiogram compared to patients with mPAP<25(Normal and boPAP; Table 2). Resting RHC showed numerically higher PCWP, cardiac output(CO), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and transpulmonary gradient (TPG = mPAP-PCWP) in patients with mPAP≥25 compared to mPAP<25.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical, radiological, lung function, and right heart catheterization data

| Measure (N=number of pts; Normal/Borderline/Resting PH) | TOTAL(N=206) | NORMAL(N=35) | BORDERLINE (N=28) | Resting PH (N=143) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | |

| NYHA classification, N(%)(N=27/26/125) | ||||||||

| 1=Dyspnea with extreme activity | 40(22.4) | 9(33.3) | 8(30.8) | 23(18.4) | ||||

| 2=Dyspnea with moderate activity | 79(44.4) | 15(55.6) | 12(46.2) | 52(41.6) | ||||

| 3=Dyspnea with minimal activity | 59(33.1) | 3(11.1) | 6(23.1) | 50(40.0) | ||||

| Modified Rodnan skin score | 9.1(8.5) | 6.0 | 8.8(8.7) | 5.0 | 7.7(6.0) | 5.5 | 9.5(8.8) | 6.0 |

| Autoantibodies, N(%) (N=34/23/128) | ||||||||

| Anticentromere ab | 43(15.7) | 4(11.8) | 4(17.4) | 35(27.3) | ||||

| Anti-Scl 70 ab | 29(15.7) | 8(23.5) | 4(17.4) | 17(13.3) | ||||

| Anti-U1RNP ab | 14(7.6) | 5(14.7) | 2(8.7) | 7(5.5) | ||||

| Anti-RNA Polymerase III ab | 5(2.7) | 1(2.9) | 0(0) | 4(3.1) | ||||

| ANA Isolated nucleolar pattern | 49(26.5) | 9(26.5) | 5(21.7) | 35(27.3) | ||||

| ANA Mixed or other staining pattern | 32(17.3) | 4(11.8) | 4(17.4) | 24(18.8) | ||||

| ANA Negative | 13(7.0) | 3(8.8) | 4(17.4) | 6(4.7) | ||||

| Pulmonary Function Test (N=30/24/128) | ||||||||

| FVC % predicted | 74.7(20.1) | 75.8 | 81.9 (18.9) | 82.8 | 69.3 (16.1) † | 66.0 | 74.1(20.7) | 76.3 |

| FVC<65% predicted, N (%) | 59(32.4) | 7(23.3) | 10(41.7) | 42(32.8) | ||||

| FVC< 70% predicted, N (%) | 74(40.7) | 9(30.0) | 16 (66.7) † | 49(38.3) | ||||

| DLco % predicted | 40.6(16.1) | 37.7 | 45.7 (10.9) | 47.5 | 40.5 (18.1) | 38.2 | 39.4(16.6) | 36.6 |

| FVC/DLco | 2.1(0.9) | 1.9 | 1.8(0.3) | 1.9 | 2.1(1.4) | 1.9 | 2.1(0.9) | 2.0 |

| HRCT fibrosis, N (%)(N=24/20/88) | ||||||||

| None | 48(36.4) | 9(37.5) | 4(20.0) | 35(39.8) | ||||

| Mild | 36(27.2) | 9(37.5) | 8(40.0) | 19(21.6) | ||||

| Moderate | 33(25.0) | 6(25.0) | 6(30.0) | 21(23.9) | ||||

| Severe | 15(11.4) | 0(0) | 2(10.0) | 13(14.8) | ||||

| 6 minute walk test, meters (N=25/23/109) | 353.7(129.9) | 384.0 | 454.3 (82.6) | 457.2 | 393.3(121.5) | 405.8 | 321.6(127.0) | 341.9 |

| Echo RVSP, mmHg (N=31/22/129)¶ | 53.0(21.0) | 50.0 | 36 .2(8.7) | 35.0 | 46.3 (13.6) ‡ | 44.0 | 58.1(21.8) | 54.0 |

| Right Heart Catheterization (RHC) | ||||||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 31(12) | 29 | 17 (3) | 17 | 24 (5) ‡ | 23 | 36(11) | 31 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 11(5) | 10 | 8 (3) | 8 | 10 (3) ‡ | 10 | 12(5) | 11 |

| CO, L/min | 5.2(1.5) | 5.1 | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.8 | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.3 | 5.1(1.6) | 5.0 |

| PVR, dyn*sec*cm-5 | 345(251) | 258 | 137(74) | 126 | 210(110) ‡ | 177 | 422(260) | 348 |

| TPG, mmHg | 20(12) | 16 | 9 (3) | 9 | 13 (6) ‡ | 13 | 24(12) | 21 |

| Exercise RHC(N=18/16/25) | ||||||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 37(10) | 37 | 31(7) | 31 | 39(7) † | 40 | 41(11) | 39 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 14(7) | 14 | 13(6) | 11 | 17(9) | 15 | 13(6) | 14 |

| CO, L/min | 7.5(2.5) | 7.0 | 8.7(2.6) | 7.9 | 7.7(1.9) | 7.2 | 6.7(2.5) | 6.4 |

| PVR, dyn*s* cm−5 | 295(215) | 215 | 175(74) | 192 | 255(215) | 212 | 391(235) | 358 |

p< 0.05;

p< 0.002 between Normal and boPAP,

Echo RVSP is the same as echo estimate sPAP in case of the absence of pulmonary valvular stenosis, FVC forced vital capacity; Echo RVSP Right ventricular systolic pressure on echocardiogram; mPAP mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PCWP pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; CO cardiac output; PVR pulmonary vascular resistance; TPG transpulmonary gradient.

BORDERLINE VS. NORMAL HEMODYNAMICS

The boPAP group had a lower mean FVC% compared to the Normal group (69.3% vs. 81.9%, p<0.05; Table 2). Although more patients in the boPAP group had fibrosis on the HRCT (80.0 vs. 62.5%), this was not statistically significant (p> 0.05). Patients with boPAP had statistically higher estimated RVSP on 2-D echocardiogram (46.3 vs. 36.2mmHg, p<0.001). On RHC, the mean mPAP was higher in the boPAP group (23.6 vs. 16.5mmHg). PCWP was also significantly higher in the boPAP group (10.2 vs. 7.9 mmHg) including 1 patient in each group with a PCWP≥16mmHg (16 and 17 mmHg, respectively). None of them had echocardiographic evidence of systolic or diastolic dysfunction. The PVR and TPG were significantly higher in the boPAP group (p<0.05 for both). Other results are presented in Table 2.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS UNDERGOING EXERCISE RHC

Thirty-four of 63 (53.9%) of the mPAP< 25 group underwent exercise RHC performed based on local standards [12–14]. On exercise, boPAP patients were more likely to have a mPAP≥30 than the Normal group; 14/16 (88%) vs. 10/18 (56%); p=0.04. The mPAP values on exercise was significantly elevated in the boPAP compared to Normal (39 vs. 30 mmHg, p<0.05). No significant differences were found between the two groups in PCWP, cardiac output or PVR (Table 2). Thirty-three percent of the Normal group vs. 44% with boPAP had PCWP≥18 mmHg during exercise (p=NS).

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS EXCLUDING PATIENTS WITH MODERATE-TO-SEVERE ILD

We further explored the impact of moderate-to-severe ILD on Normal vs. boPAP groups. We excluded 26 patients with either moderate-to-severe fibrosis on HRCT or an FVC<65% predicted (Figure 1). Twenty nine patients, 21[72%] of the Normal, and 8[28%] of the boPAP groups were included (Table 3); others were excluded because of missing FVC and HRCT data. On echocardiogram, the mean (SD) estimated RVSP in the boPAP group was 45 (10.8) mmHg compared to 37(9.5) mmHg in the Normal group (p=0.14). Resting hemodynamics showed significantly higher mPAP and PVR in the boPAP vs. Normal group (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

RHC excluding patients with significant ILD

| NORMAL(N=21) | BORDERLINE(N=8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Median | Mean(SD) | Median | |

| Resting RHC | ||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 16(3) | 16 | 26(9) † | 23 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 5.5(1.3) | 5.1 | 5.4(0.9) | 5.5 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 8 (4) | 8 | 11 (4) | 11 |

| PVR, dyn*sec*cm−5 | 136(68) | 136 | 260(183) ‡ | 217 |

| TPG, mmHg | 8 (3) | 9 | 15 (10) ‡ | 12 |

| Exercise RHC (N=12/6/7) | ||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 33(7) | 31 | 42(5) ‡ | 43 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 9.2(3.0) | 9.3 | 7.6(1.7) | 7.8 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 14(5) | 14 | 19(13) | 15 |

| PVR, dyn*sec*cm−5 | 181(83) | 192 | 346(377) | 199 |

p<0.001,

p<0.05 between Normal and boPAP,

4 Normal and 4 boPAP patients were not classifiable due to missing HRCT/ PFT values

Eighteen of these 21 patients underwent exercise RHC (Table 3). Mean(SD) value of mPAP for the boPAP group was higher than the Normal group; 42(5) mmHg vs. 33(7) mmHg (p=0.02). No other exercise hemodynamics reached significant difference (Table 3).

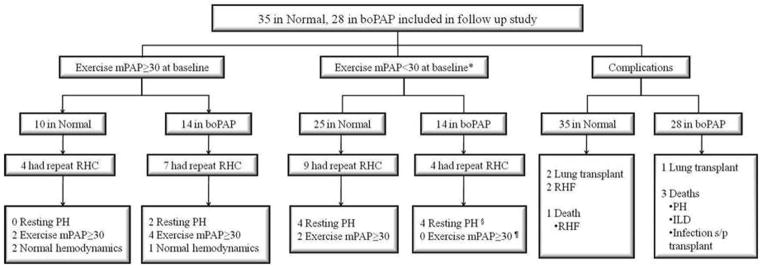

FOLLOW UP DATA ON PATIENTS WITH BORDERLINE AND NORMAL HEMODYNAMICS

As of January 2011, 24 (38%) patients (13 from the Normal group, 11 from the boPAP group) underwent repeat hemodynamic evaluation (Figure 2). Patients had repeat RHCs predominantly due to progressive unexplained dyspnea and was left at the discretion of the investigators. There were no pre-defined criteria for repeat RHC. The mean (SD) follow up period was 25.7(16.4) months, and the mean time between the initial and followup RHCs was 13.67(8.16) months (boPAP vs. Normal NS; Table 4).

Figure 2.

Follow up flow diagram of patients with mPAP<25 mmHg at initial RHC in the PHAROS registry RHF-right heart failure; ILD-interstitial lung disease

Table 4.

Follow up data as of January, 2011

| NORMAL(N=35) | BORDERLINE(N=28) | |

|---|---|---|

| Follow up period, months, mean(SD) | 26.53(15.48) | 24.69(17.72) |

| Repeat RHC | 13 | 11 |

| Time to repeat RHC, months, mean(SD) | 14.92(9.23) | 12.19(6.82) |

| Results | ||

| Normal | 4 | 2 |

| Exercise mPAP>30mmHg | 5 | 4 |

| Resting PH | ||

| PAH | 3 | 3 |

| PVH | 0 | 2 |

| PH-ILD | 1 | 1§ |

| Complications | ||

| PH-related | ||

| Lung transplant | 2 | 1 |

| Right sided heart failure | 2 | 0 |

| Non PH-related | ||

| Left heart failure | 1 | 0 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 | 0 |

| Lung cancer | 1 | 0 |

| Severe restrictive lung disease | 0 | 2 |

| Death | ||

| Due to PH complications | 1(Right heart failure) | 2(severe PAH, transplant) |

| Due to non PH complications | 1(lung cancer) | 1(ILD) |

| Reason unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Lost to follow up | 5 | 2 |

| PH specific medications(overall / for PH only) | ||

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 6/5 | 15/14 |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | 5/4 | 8/7 |

| Prostacyclin | 2/2 | 1/1 |

| Combinations of the above | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| Other medications | ||

| Immunosuppressives | 4† | 2‡ |

| Nasal O2 | 3 | 9 |

| NYHA class at followup | ||

| 1= Dyspnea with extreme activity | 8 | 8 |

| 2= Dyspnea with moderate activity | 14 | 9 |

| 3= Dyspnea with minimal activity | 5 | 6 |

| 4= Dyspnea at rest | 0 | 1 |

| General health status at followup | ||

| Well/Same | 25 | 18 |

| Worse | 5 | 7 |

| Lost follow up/unknown | 5 | 3 |

PAH= pulmonary arterial hypertension, PVH= pulmonary venous hypertension, ILD= interstitial lung disease

1 patient was diagnosed with severe PH-ILD on repeat echocardiogram

1 on mycophenolate mofetil, 1 on azathioprine, 1 on cyclophosphamide, 1 on transplant rejection prevention medications

1 on rituximab, 1 on mycophenolate mofetil

In the Normal group, 4 (32% of the 13 who had a repeat RHC) developed resting PH during followup (Table 4, Figure 2). In contrast, repeat RHC in the boPAP group revealed that 6 patients (55% of 11 with repeat RHC) developed resting PH.. The mean time to developing resting PH was 17.10(10.59) months in the Normal group and 18.85(10.95) months in the boPAP group (p=NS). Four of the 10 patients with exercise mPAP>30mmHg in the Normal group had a repeat exercise hemodynamic evaluation; none developed resting PH during follow up, 2 had exercise mPAP<30mmHg, and 2 continued to achieve exercise mPAP>30mmHg . Of the 14 boPAP patients with exercise mPAP>30mmHg at baseline, 7 had repeat RHCs during follow up and 2 developed resting PH.

Complications including death

PH-related complications were also investigated during the follow up period (Figure 2). In the Normal group, 2 patients underwent lung transplantation for ILD and 2 patients developed right sided heart failure (RHF), including one patient who died (the 2 patients with RHF both showed resting PAH on repeat RHC). Non PH-related major complications in the Normal group included left sided heart failure, myelodysplastic syndrome and metastatic lung cancer (the patient that developed lung cancer eventually died). In the boPAP group, there was one death due to resting PH that was associated with severe ILD. An additional death was due to progressive pulmonary fibrosis, and another due to bacterial infection after lung transplantation.

Treatment

Eighteen patients in the boPAP group and 11 in the Normal group were treated with PH specific medications (64% vs. 31%; p=0.009). Among the 28 patients initially classified as boPAP, 6 were receiving treatment for newly developed resting PH, 11 for either prior or newly diagnosed exercise PH, and 1 for severe Raynaud’s phenomenon. Of the 11 patients in the Normal group who were receiving PH specific treatments, 3 were for newly developed PH and 5 were treated for prior or newly diagnosed exercise PH. Other indications for initiating PH medications in the Normal group included severe Raynaud’s phenomenon(n=2) and plexiform lesions seen on open lung biopsy(n=1).

Patients in the boPAP group had a trend towards a worse survival (HR 1.80, 95% confidence interval 0.40–8.05) compared to the Normal group (p=0.44) but was not statistically significant. The 3-year survival was 87% for Normal group vs. 83% for boPAP group.

DISCUSSION

PAH is now the leading cause of SSc related mortality[1, 4–6]. Observational studies in SSc have focused on patients with definite PH and the natural course and prognosis is well documented. Risk factors for developing PAH in SSc include limited cutaneous SSc, older age at disease onset, severity and duration of Raynaud’s phenomenon, elevated estimated RVSP on echocardiogram, a decreased DLCO or a progressive decline of DLCO, and an increased FVC%/DLCO% predicted ratio>1.6[15–19].

Historical survival in SSc-PAH has ranged between 40–50% at 2 years after diagnosis of PAH[15, 20]. Survival has somewhat improved during the last decade and ranges between 47–56% at 3 years, likely due to early screening and availability of PAH-specific therapies[8, 21, 22]. This recent modest improvement in survival raises the question whether early diagnosis/treatment of PAH or treatment of pre-PAH will improve long term outcomes. However, we do not know if borderline elevations in pulmonary artery pressures on RHC are predictive of future PAH. In this regard, a boPAP group on RHC may predict clinically relevant PAH[3].

We assessed the baseline characteristics, morbidity and mortality in patients with Normal and boPAP in a large observational cohort of patients “at-risk” of developing SSc-PH. When we compared patients that had resting PH to patients with mPAP<25mmHg, we found patients with resting PH had worse symptoms, lower DLCO % predicted, higher estimated RVSP on echocardiogram, and higher PCWP, TPG, PVR on baseline RHCs. Among patients with mPAP<25mmHg we found that patients with boPAP had greater evidence of restrictive lung disease, higher estimated RSVP on echocardiogram, and a higher PVR and TPG on resting RHC than patients with Normal hemodynamics. In those patients who underwent exercise hemodynamic assessments, 88% in boPAP vs. 56% in the Normal group had evidence of elevated exercise mPAP (mPAP > 30 mmHg; p=0.04). Baseline demographics did not differentiate the Normal vs. boPAP groups. When we excluded patients with moderate-to-severe ILD (FVC≤65% predicted and/or HRCT chest with moderate to severe fibrosis), we still found higher estimated RVSP on echocardiogram and elevated PVR and TPG on RHC in boPAP vs. Normal.

Previous studies have explored the association between elevated resting mPAP on RHC in SSc and elevated exercise mPAP. Baseline resting mPAP between 19–21 mmHg were associated with exercise mPAP≥30mmHg in 3 studies[12, 13, 23]. Exercise physiology on RHC is a focus of intense debate in the PH literature. In a systematic review, Kovacs and colleagues showed that submaximal exercise during RHC in healthy volunteers (based on 10 studies, N=193) led to an increased mPAP of >30 mmHg in approximately 20% of subjects <50 years of age, and in nearly half≥50 years of age[3]. This led to removal of exercise PH from the definition of PAH[2]. However, exercise mPAP≥30mmHg may be an important intermediate step in “at risk” populations [12, 13, 23–26]. This is supported by a longitudinal study that followed 42 patients with SSc-related elevated exercise mPAP. Nineteen percent of these patients developed resting PAH after a mean (SD) time of 30(16) months, and of those, 4 (9.5%) patients died due to PH related complications within 3 years[21]. In the current study, a greater percentage of patients with boPAP also had exercise mPAP≥30mmHg compared to the Normal group at baseline (88% vs. 56%, p=0.04). Longitudinal follow up on 14 boPAP patients with elevated exercise mPAP disclosed the development of resting PH in 2 (18%). In contrast, none of the 4 patients in the Normal group with exercise mPAP≥30mmHg who had a repeat RHC demonstrated newly developed resting PH. Abnormal exercise hemodynamic profiles in SSc may represent an abnormal hemodynamic phenotype which is part of a continuum from normal to resting PH.

The mean follow up period for our patient group was 25.7 months, during which 13 and 11 patients in the boPAP and Normal groups, respectively underwent repeat RHCs. Fifty five percent of the borderline group and 32% of the Normal group developed resting PH (p=0.41), although more in the boPAP group had PVH or PH-ILD than in the Normal group. Another study by Schriber and colleagues, presented as an abstract, also assessed their prospective cohort of patients with boPAP and Normal hemodynamics[27]. During follow up at 5 years, 58% of the boPAP group vs. 30% of the Normal group had progressed to resting PH and PVR > 200 dynes.s.cm-5 was an independent predictor of progression to resting PH. Our study also supports the significance of PVR as there is a statistically significant difference in PVR between the Normal(137 at rest) and boPAP group(210 at rest) at baseline resting RHC, and the significance is maintained after the exclusion of patients with moderate to severe ILD.

There were 7 deaths (4 boPAP and 3 Normal). Of these, 2 boPAP and 1 Normal deaths were due to PH-related complications (HR=1.80, p=NS). Since the majority of the patients were recruited in an era when exercise PH was part of the definition of PH, these patients were treated with PAH-specific therapies. This is exemplified by our data where a significantly higher proportion of patients in the boPAP group (11/14 or 78.6%) with exercise mPAP≥30mmHg were receiving PAH specific treatments. We noted an increased frequency of resting PH and increased mortality in the boPAP group, but these numbers may have been underestimated due to concomitant PAH therapies.

Our study has significant strengths. First, this was a longitudinal study in SSc patients to describe the differences between patients with boPAP and normal hemodynamics including both baseline and follow up RHCs. Second, our study is a multicenter study that involves 16 scleroderma centers. Finally, we followed a “real-life” cohort of patients with SSc, and included patients with ILD, a frequent finding in this population. Our data was robust after excluding patients with moderate-to-severe ILD.

Our study is not without limitations. First, given the design of the study as an observational cohort, a heterogenous population and missing data were unavoidable. Second, longitudinal follow up, diagnostic (such as repeat RHC) and treatment decisions were based on the discretion of the treating physician and thus limited homogeneity. Third, it was not feasible to study the natural history of boPAP and Normal since patients, particularly those with exercise mPAP≥30mmHg were treated with PH specific therapy based on previous definition of PAH that included exercise component. Although we do not endorse the use of these medications without the diagnosis of resting PAH, this reflects real life practices. Future studies may include further subgroup analyses on patients with/without ILD or RV dysfunction based on predictive parameters such as NT-proBNP. Furthermore, identifying the role of exercise pulmonary hemodynamics in the evaluation of pulmonary vascular disease and developing a standardized approach for when and how to perform exercise pulmonary hemodynamics, in the context of an evidence-based definition, is clearly needed.

In conclusion, this is a prospective observational study that separates SSc patients without resting PH into boPAP and Normal groups on the basis of RHC, describing the baseline characteristics and followup data. Patients with BoPAP have a greater prevalence of abnormal lung physiology, pulmonary fibrosis and presence of exercise mPAP≥30mmHg compared to patients with mPAP≤20mmHg. Further longitudinal studies will be needed to confirm these findings and to validate the importance of identifying and prognosticating boPAP patients.

Acknowledgments

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Study conception and design was done by Dr. Sangmee Bae, Rajeev Saggar, Virginia Steen and Dinesh Khanna. Individual centers provided patient data through the PHAROS registry and additional information required was further requested and acquired by Sangmee Bae and Dinesh Khanna. Analysis and critical interpretation of the data was done by Bae, Saggar, Steen, Maranian and Khanna. PHAROS registry is funded by unrestricted grant by Actelion Inc and Gilead Inc and the Scleroderma Foundation. Dinesh Khanna, MD, MS was supported by a National Institutes of Health Award (NIAMS K23 AR053858-05).

Abbreviations

- boPAP

borderline

- mPAP

mean pulmonary arterial pressure

- DLCO

diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- HRCT

high resolution computed tomography of the chest

- mPAP

mean pulmonary arterial pressure

- NS

not significant

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- PFT

pulmonary function test

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PH-ILD

pulmonary hypertension secondary to interstitial lung disease

- PVH

pulmonary venous hypertension

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- RHC

right heart catheterization

- RVSP

right ventricular systolic pressure

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- SSc

systemic sclerosis

- TPG

transpulmonary gradient

Contributor Information

Sangmee Bae, Email: sbae04@gmail.com.

Rajeev Saggar, Email: rsaggarmd@gmail.com.

Marcy B. Bolster, Email: bolsterm@musc.edu.

Lorinda Chung, Email: shauwei@stanford.edu.

M. E. Csuka, Email: mecsuka@mcw.edu.

Chris Derk, Email: chris.derk@jefferson.edu.

Robyn Domsic, Email: rtd4@pitt.edu.

Aryeh Fischer, Email: FischerA@njhealth.org.

Tracy Frech, Email: Tracy.Frech@hsc.utah.edu.

Avram Goldberg, Email: AuGoldbe@nshs.edu.

Monique Hinchcliff, Email: mehinchcliff@gmail.com.

Vivien Hsu, Email: hsuvm@umdnj.edu.

Laura Hummers, Email: lhummers@jhmi.edu.

Elena Schiopu, Email: eshiopu@umich.edu.

Maureen D. Mayes, Email: maureen.d.mayes@uth.tmc.edu.

Vallerie McLaughlin, Email: vmclaugh@med.umich.edu.

Jerry Molitor, Email: jmolitor@umn.edu.

Nausheen Naz, Email: Nausheen.Naz@umassmemorial.org.

Daniel E. Furst, Email: defurst@mednet.ucla.edu.

Paul Maranian, Email: pmaranian@mednet.ucla.edu.

Virginia Steen, Email: steenv@georgetown.edu.

Dinesh Khanna, Email: khannad@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119(16):2250–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs G, Berghold A, Scheidl S, et al. Pulmonary arterial pressure during rest and exercise in healthy subjects: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(4):888–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00145608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin V, Humbert M, Coghlan G, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: the most devastating vascular complication of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(Suppl 3):iii25–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steen VD, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and severe pulmonary fibrosis in systemic sclerosis patients with a nucleolar antibody. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(11):2230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steen VD. The lung in systemic sclerosis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11(1):40–6. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000152147.38706.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heartand Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493–537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badesch DB, Champion HC, Sanchez MA, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 Suppl):S55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinchcliff M, Fischer A, Schiopu E, et al. Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS): baseline characteristics and description of study population. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(10):2172–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preliminary criteria for theclassification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(5):581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(2):202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steen V, Chou M, Shanmugam V, et al. Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis. Chest. 2008;134(1):146–51. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saggar R, Khanna D, Furst DE, et al. Exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis: four distinct entities. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(12):3741–50. doi: 10.1002/art.27695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen VD, Champion H. Is exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension ready for prime time in systemic sclerosis? Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2011;(169):1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steen V, Medsger TA., Jr Predictors of isolated pulmonary hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis and limited cutaneous involvement. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):516–22. doi: 10.1002/art.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang B, Schachna L, White B, et al. Natural history of mild-moderate pulmonary hypertension and the risk factors for severe pulmonary hypertension in scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox SR, Walker JG, Coleman M, et al. Isolated pulmonary hypertension in scleroderma. Intern Med J. 2005;35(1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plastiras SC, Karadimitrakis SP, Kampolis C, et al. Determinants of pulmonary arterial hypertension in scleroderma. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):392–6. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukerjee D, St George D, Knight C, et al. Echocardiography and pulmonary function as screening tests for pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(4):461–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stupi AM, Steen VD, Owens GR, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in the CRESTsyndrome variant of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(4):515–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(2):151–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-953OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathai SC, Hummers LK, Champion HC, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension associated with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases: impact of interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(2):569–77. doi: 10.1002/art.24267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovacs G, Maier R, Aberer E, et al. Borderline pulmonary arterial pressure is associated with decreased exercise capacity in scleroderma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(9):881–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0563OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichenberger F, Voswinckel R, Schulz R, et al. Noninvasive detectionof early pulmonary vascular dysfunction in scleroderma. Respir Med. 2009;103(11):1713–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alkotob ML, Soltani P, Sheatt MA, et al. Reduced exercise capacity and stress-induced pulmonary hypertension in patients with scleroderma. Chest. 2006;130(1):176–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins N, Bastian B, Quiqueree L, et al. Abnormal pulmonary vascular responses in patients registered with a systemic autoimmunity database: Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Screening Evaluation using stress echocardiography (PHASE-I) Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(6):439–46. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schreiber B, Valerio C, Handler C, et al. Predictors of progression to pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis[Abstract] Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70 (Suppl3):168. [Google Scholar]