SUMMARY

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein complex essential for maintenance of telomere DNA at linear chromosome ends. The catalytic core of Tetrahymena telomerase comprises a ternary complex of telomerase RNA (TER), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and the essential La family protein p65. NMR and crystal structures of p65 C-terminal domain and its complex with stem IV of TER reveal that RNA recognition is achieved by a novel combination of single- and double-strand RNA binding, which induces a 105° bend in TER. The domain is a cryptic, atypical RNA recognition motif with a disordered C-terminal extension that forms an α-helix in the complex necessary for hierarchical assembly of TERT with p65-TER. This work provides the first structural insight into biogenesis and assembly of TER with a telomerase-specific protein. Additionally, our studies define a structurally homologous domain (xRRM) in genuine La and LARP7 proteins and suggest a general mode of RNA binding for biogenesis of their diverse RNA targets.

INTRODUCTION

Telomerase is an RNA-protein particle (RNP) that extends the G-rich strands of the telomere repeat DNA at the ends of linear chromosomes (Blackburn and Collins, 2011; Greider and Blackburn, 1985). Most somatic cells have low levels of telomerase activity, resulting in telomere attrition due to incomplete replication of telomere ends, which leads to cellular senescence or apoptosis (Bertuch and Lundblad, 2006; Shay and Wright, 2011; Wong and Collins, 2003). In contrast, most cancer cells have high levels of telomerase activity, an important element of cancer etiology (Shay and Wright, 2011). Telomerase insufficiency due to mutations in telomerase components that affect biogenesis or catalysis has been linked to dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia, pulmonary fibrosis, and other diseases (Artandi and DePinho, 2010; Chen and Greider, 2004; Walne and Dokal, 2009). Telomerase is composed of telomerase RNA (TER), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and several additional proteins required for assembly and activity in vivo (Blackburn and Collins, 2011; Podlevsky and Chen, 2012). TER provides the template for the telomere synthesis, and plays essential roles in assembly, localization, accumulation, and catalytic activity (Cunningham and Collins, 2005; Theimer and Feigon, 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). TERT has the active site along with RNA and DNA binding activities (Autexier and Lue, 2006; Blackburn and Collins, 2011; Lingner et al., 1997; Mason et al., 2011). The structural roles and mechanism of the telomerase-specific accessory proteins in biogenesis, assembly, and catalysis remain largely unknown.

Tetrahymena p65 is a telomerase holoenzyme protein essential for TER accumulation in vivo (Witkin and Collins, 2004). In the Tetrahymena holoenzyme TER, TERT, and p65 comprise a stable catalytic core complex and p75, p45, and p19 comprise a telomere adaptor subcomplex (TASC) (Min and Collins, 2009, 2010; Witkin and Collins, 2004). Formation of the catalytic core complex is independent of TASC assembly, which is required for telomere maintenance (Min and Collins, 2009). Biochemical and FRET studies have shown that hierarchical assembly of the catalytic core starts with the binding of p65 to TER, which results in a conformational change in TER that facilitates the binding of TERT to the p65-TER complex (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Prathapam et al., 2005; Stone et al., 2007). p65 and its ortholog from the ciliate Euplotes aediculatus, p43 (Aigner et al., 2003), have been classified as La-related proteins group 7 (LARP7) (Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009). Genuine La and LARP proteins are RNA chaperones for diverse RNA targets, including mRNA, tRNAs, snRNAs, snoRNAs, and 7SK RNA (Wolin and Cedervall, 2002; Bayfield et al., 2010; Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009). Four domains of p65, N-terminal, La motif (LAM), RNA recognition motif (RRM), and C-terminal (Figure 1A), have been proposed to interact with specific sites in stem I and stem-loop IV of TER (Figure 1B), and binding of the unique C-terminal domain of p65 in particular requires the region of stem IV around the central di-nucleotide GA bulge (Akiyama et al., 2012; O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Prathapam et al., 2005). p65 also stimulates conformational changes in other parts of TER, and it stabilizes TER and TERT in catalytically active conformations (Berman et al., 2010). Interaction of the p65 C-terminal domain with TER is necessary and sufficient for the hierarchical assembly of the TERT-TER-p65 catalytic core (Akiyama et al., 2012; O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Prathapam et al., 2005). Here we report the first structure of a complex of a telomerase-specific protein with telomerase RNA. Analysis of the structures of p65 C-terminal domain free and in complex with stem IV of TER and biochemical data reveal how p65 functions in telomerase biogenesis and assembly. Our studies define a new class of RRM with a C-terminal extension that forms a helix in complex with RNA (xRRM) and suggest that its mode of RNA binding is common to genuine La and LARP7 proteins for biogenesis of their diverse targets.

Figure 1. Structure of p65 C-terminal domain.

(A) Domain structure of p65 and p65 C-terminal domain constructs. (B) Sequence and secondary structure of Tetrahymena TER and stem IV constructs. TBE indicates the template boundary element. (C–E) Solution NMR structure of p65-C2ΔL1: (C) Ensemble of the 20 lowest energy NMR structures, (D) Lowest energy structure; side view of β-sheet. Atypical features are highlighted: α3 (red), β4’ (lime-green), long β2-β3 loop (gray), non-aromatic residues at conserved positions on β3 RNP1 (cyan) and β1 RNP2 (violet), and location of the start of the C-terminal tail (red ★), (E) Cartoon rendering of lowest energy structure. The position of the β2-β3 loop is indicated by gray dots. (F) Crystal structure of p65-C1ΔL2 in cartoon rendering. In C–F, the β-sheet is orange, α3 is red, the β2-β3 loop is gray, and the rest of the protein is light orange.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

p65 C-terminal domain is a cryptic atypical RRM

Although p65 C-terminal domain binds RNA, global BLAST searches for homologous sequences and putative domains using the p65 C-terminal domain did not identify a known protein fold. To define the domain boundaries, we made a series of C-terminal domain constructs (Figure 1A and Figure S1). p65-C(369–542) [hereafter, p65-C1] gave a protein with a reasonably good 1H-15N HSQC spectrum indicative of a folded protein (Figure S1C). Analysis of this spectrum indicated that 22 residues at the C-terminus were disordered, so these were deleted to make p65-C2 (Figure 1A and Figure S1D). Lastly, internal residues 421–442 were deleted to make p65-C1ΔL1 (residues 369–542Δ421–442) and p65-C2ΔL1 (residues 369–519Δ421–442), respectively (Figure 1A and Figure S1F and S1G), since residues ~413–459 exhibited few NOEs, and chemical shift indexing and heteronuclear NOE analysis (Figure S1E and see Experimental Procedures) indicated that this region of the protein is random coil. Comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of p65-C1ΔL1 and p65-C2ΔL1 with p65-C1 and p65-C2 spectra respectively (Figure S1C, S1D, S1F, and S1G) showed that the internal loop deletion did not change the folding of the domain. As shown below, deletion of these internal residues also did not significantly affect RNA binding.

A solution NMR structure of p65-C2ΔL1 was solved to rmsd of 0.26 Å for the 20 lowest energy structures (Figure 1C and Table S1). The structure reveals that the overall fold of p65 C-terminal domain is an RRM, but with several atypical features (Figure 1D). The p65-C2ΔL1 RRM has a β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4'-β4-α3 topology, with a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (Figure 1C–1E). Atypical features of p65 C-terminal RRM are the presence of a short β4’ strand, the absence of the consensus RNP1 and RNP2 sequences on the β3 and β1 strands, respectively, with three aromatic residues that generally recognize two nucleotides, and a non-canonical third helix, α3 (residues 504–517) that lies directly across the middle-upper surface of the “RNA binding” face of the β-sheet (Figure 1C and 1D). C-terminal α-helices have been observed in some RRMs, but with varying orientations and proposed functional roles (Alfano et al., 2004; Allain et al., 1996; Clery et al., 2008; Jacks et al., 2003; Martin-Tumasz et al., 2011; Oubridge et al., 1994; Varani et al., 2000). An unusual feature of p65 C-terminal RRM is the presence of the 47 residue (413–459) loop between β2 and β3 (β2-β3 loop), which in p65-C2ΔL1 was truncated to 21 residues (Figure 1A and 1D and Figure S1E). Typically, β2-β3 loops are <10 residues (Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009), and a β2-β3 loop of this size is unprecedented to our knowledge. The insertion of a 47 residue β2-β3 loop provides a structural explanation for why an RRM fold was not predicted for the p65 C-terminal domain. Intriguingly, based on the structure and a DALI search (Holm and Rosenstrom, 2010) using p65-C2ΔL1 as a probe, the overall fold of p65 C-terminal domain is most similar to human La protein (hLa) RRM2 (Figure S2A) (Jacks et al., 2003).

Based on the solution structure and NMR data, the remaining flexible residues of the β2-β3 loop and five N-terminal residues were deleted to make construct p65-C1ΔL2 (375–542Δ413–459), which yielded crystals that diffracted to 2.5 Å (Figure 1A and Figure S2B and Table S2). This protein construct retains the C-terminal 22 residues deleted in the NMR solution structure. The crystal structure (Figure 1F) is the same as the solution structure except that the β2 and β3 strands are each one residue shorter at the β2-β3 end and there is a small difference in the position of the β-sheet (Figure S2C). Significantly, no electron density is observed for the C-terminal tail of the RRM, which NMR analysis indicates is unstructured in solution.

TER binding by p65-C requires the C-terminal tail but not the β2-β3 loop

Since the binding site for p65-C includes the region of TER stem IV encompassing the GA bulge (O'Connor and Collins, 2006), we designed a minimal stem IV hairpin (S4) containing 4 base pairs on either side of the GA bulge and capped by a UUCG tetraloop (Figure 1B). In TER, the proximal stem IV contains a bulge U three base pairs from the GA bulge, but deletion of this non-conserved bulge U has no effect on activity (Richards et al., 2006). Gel mobility shift assays of p65-C1 with S4, a longer stem IV construct, and stem-loop IV all gave comparable results (Figure S3A–S3D). Gel mobility shift assays did not show any interaction between p65-C1 and two control RNAs in which the GA bulge was deleted (S4-ΔGA) or replaced by UU (S4-UU) (Figure S3E and S3F). NMR titration of S4 or longer RNAs into a sample of p65-C1 resulted in shifting and/or broadening of many of the crosspeaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra, indicating formation of a complex in slow-to-intermediate exchange on the NMR time scale (Figures S4A–S4C). These results indicate that our minimal stem IV is sufficient for specific binding of p65-C1. Stoichiometric gel mobility shift and NMR titration experiments show that truncation of the β2-β3 loop does not significantly affect RNA binding to S4 and binding is specific for the GA bulge (Figure S4D–S4F). In contrast deletion of the C-terminal tail in p65-C2 or p65-C2ΔL1 abolished both the gel shift and S4 interaction as judged by NMR (Figure S3G, S3H, S4G, and S4H).

To quantify the strength of the interaction between p65-C and S4, equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values were measured using isothermal calorimetry (ITC) (Figure 2 and S5, and Table 1). The p65-C1:S4 and p65-C1ΔL1:S4 complexes have comparable KDs of 36.4±3.6 nM and 50.6±7.1 nM, respectively (Figure 2A and 2B). This confirms that partial deletion of the β2-β3 loop has little if any impact on RNA binding. Complete deletion of the β2-β3 loop in p65-C1ΔL2, which yielded crystals, has a small effect on RNA binding, decreasing the affinity <3-fold (Figure 2C). Binding affinities for interactions between p65-C1, p65-C1ΔL1, and p65-C1ΔL2 and S4-UU or S4-ΔGA were 50–80 fold lower than the same proteins and S4 (Table 1 and Figure S5A–S5F). No interaction was detected between p65-C2 or p65-C2ΔL1 and RNA by ITC, indicating that the KD must be >1mM (Figure 2D and Figure S5G). These results confirm that specific interaction of p65 C-terminal domain with RNA requires a GA bulge flanked by helices, that the β2-β3 loop does not play any apparent role in binding to TER stem IV, and that the p65 C-terminal 22 residues are essential for high affinity RNA binding. RNA interaction by the isolated C-terminal tail residues 515–543 (p65-T) is ~30 fold weaker than by p65-C1 (Figure S5H and Table 1), indicating that high affinity binding requires both the atypical RRM and the C-terminal tail.

Figure 2. Isothermal calorimetry of p65 C-terminal domain with TER stem IV.

(A–F) Isothermal calorimetry data and analysis for titration of S4 RNA into (A) p65-C1, (B) p65-C1ΔL1, (C) p65-C1ΔL2, (D) p65-C2, (E) p65-C1ΔL2 Y407A, and (F) p65-C1ΔL2 R465A. ITC data for other constructs is shown in Figures S5.

Table 1.

Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) and stoichiometry constant (n) values determined using ITC measurements for p65-C constructs with TER stem IV constructs.

| Protein | RNA | KD (nM) | N& |

|---|---|---|---|

| p65-C1 | S4 | 36.4±3.6 | 1.1±0.01 |

| p65-C1ΔL1 | S4 | 50.3±7.1 | 1.2±0.01 |

| p65-C1ΔL2 | S4 | 101±21.2 | 1.2±0.02 |

| p65-C1 | S4-UU | 1736±153 | 1.4±0.03 |

| p65-C1ΔL1 | S4-UU | 2551±156 | 1.4±0.04 |

| p65-C1ΔL2 | S4-UU | 1311±120 | 1.9±0.04 |

| p65-C1 | S4-ΔGA | 2985±220 | 1.5±0.04 |

| p65-C1ΔL1 | S4-ΔGA | 2340±190 | 1.7±0.04 |

| p65-C1ΔL2 | S4-ΔGA | 2433±432 | 1.8±0.04 |

| p65-C2 | S4 | n.b.* | n.a.# |

| p65-C2ΔL1 | S4 | n.b.* | n.a.# |

| p65-T | S4 | 926±220 | 1.8 |

| p65-C1ΔL2 Y407A | S4 | 374.5±26.6 | 1.2±0.02 |

| p65-C1ΔL2 R465A | S4 | 638.6±46.8 | 1.3±0.01 |

no binding

not applicable

Significant deviations from a stoichiometry of 1:1 were only observed for weak binding complexes, consistent with a decrease in binding specificity.

Crystal structure of p65-C with stem IV of TER

A complex of p65-C1ΔL2 with S4 was crystallized and the structure was solved to 2.6 Å (Figure 3A and Figure S6 and Table S2). Although S4 is a hairpin in solution, it crystallizes as a dimer, forming two symmetrical binding sites for protein (Figure S6A and S6B). Dimerization of the RNA retains the native binding site, with the non-native UUCG hairpin-loop paired as a duplex in the center, outside the binding site. In the complex, the C-terminal tail that is unstructured in the free protein forms an α-helical extension of helix α3 (hereafter called α3x), resulting in a single long C-terminal α-helix with clear electron density visible up to residue 531 (Figure 3A). This helical extension binds across the major groove of S4 in the region corresponding to the top of proximal stem IV and wedges open the C-G base pairs on either side of the GA bulge, resulting in a 105° bend in the RNA (Figure 3B and 3C). Both bases of the GA bulge are extruded out of the helix and interact with residues on the RRM (Figure 3A). Insertion of an alpha helix in the major groove of RNA at an internal loop was first observed for the Rev peptide (Battiste et al., 1996), but without the significant bend of the RNA helix that arises from the combination of the single and double-strand interactions with the p65 RRM2 β-sheet and α3x.

Figure 3. Crystal structure of p65 C-terminal domain with TER stem IV.

(A) Two views of the p65-C1ΔL2:S4 complex. (B) Schematic of the protein-RNA interactions, (C) Stick rendering of the RNA on the surface of the protein, illustrating the 105° bend induced by protein binding. (D) Protein interactions with the GA bulge. (E) View of α3x in the major groove. Aromatic side chains that wedge open the base pairs adjacent to the GA bulge and other residues that interact with the RNA are labeled. Protein color scheme is as in Figure 1. Gua, Ade, and Cyt that contact the protein are green, magenta, and cyan, respectively, and the rest of the RNA is light blue.

The bulge Gua121 is inserted into the interface between residues on the β-sheet and helix α3. A remarkable number of hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions stabilize Gua121 in this binding pocket (Figure 3B and 3D). The N1 and N2 amino on the Watson-Crick face are hydrogen bonded to the side chain of Asp409 on β2 and the N7 and O6 on the Hoogsteen face are hydrogen bonded to Arg465 side chain on β3. Tyr407 on β2 stacks directly below the Gua121 base, and the aliphatic part of the α3 Lys517 side-chain stacks above it. The Tyr407 hydroxyl group is within hydrogen bond distance of both the phosphate O2 and the Gua121 ribose 2’OH. The bulge Ade122 base is perpendicular to both Gua121 and Tyr407, and the side chain of Gln467 at the beginning of the β3-α2 loop stacks on the other side of Ade122. In contrast to Gua121, Ade122 is not sandwiched between α3 and the β-sheet, but rather is located on the region of the β-sheet above α3. Remarkably, the same Arg465 that recognizes the Hoogsteen face of Gua121 also recognizes the Hoogsteen face of the bulge Ade121, with its backbone carbonyl oxygen hydrogen bonded to Ade121 N6 and its sidechain amino hydrogen bonding to Ade121 N7 (Figure 3D).

Helix α3x that binds across the major groove at the top of proximal stem IV is not linear with the rest of helix α3, but rather bends ~12° where it contacts the dsRNA (Figure 3A). Stacking of the conserved C-G base pairs on either side of the GA bulge is completely disrupted and these base pairs are rolled open toward the major groove. Three aromatic residues on helix α3 are inserted between these base pairs; the aromatic rings of Phe521 and Phe524 are perpendicular to the base planes, wedging them open, while Phe525 stacks directly on Gua147, below and perpendicular to Phe524 (Figure 3B and 3E). The interaction of helix α3x with the dsRNA is further stabilized by other side chain interactions with phosphates of Gua146, Gua147, and Cyt120.

Structural changes in the p65 C-terminal domain upon telomerase RNA binding

Except for the formation of the extended helix α3 on RNA binding from a disordered tail in the free protein, there are only small changes in the rest of the RRM (Figure 4A). Compared to the free protein crystal structure, in the complex helix α3 moves slightly away from the β-sheet surface to accommodate the GA bulge, and strand β2 and β3 are extended by one residue each and show a small change in orientation to one that is similar to the solution structure of the free protein. Among the residues from β2 and β3 that interact with the GA bulge only Tyr 407 moves significantly, flipping down to stack on Gua121 (Figure 4A). This suggests that the binding pocket for the GA bulge (Figure 4B) is preformed in the free protein and Tyr407 locks the RNA in place.

Figure 4. Comparison of free and bound protein and RNA.

(A) Superposition of p65-C1ΔL2 free (green) and in complex with S4 (red). Side chains that form the GA bulge-binding pocket are shown. (B) The GA bulge residues in the protein-binding pocket. (C, D) Structures of the GA bulge and adjacent C–G base pairs in the (C) free RNA (PDB ID 2FEY) and (D) bound RNA, and schematics of the bend size and angle. RNA bend angles (tilt and roll) were measured using the program CURVES 5.1 (Lavery and Sklenar, 1988).

A dramatic change in the telomerase RNA structure upon p65 C-terminal domain binding

In contrast to the small changes in the protein structure, the RNA undergoes a large conformational change upon binding to protein. The central GA bulge and the G-C base pairs that flank the bulge are absolutely conserved in Tetrahymena ciliates. In the solution structure of stem-loop IV, Ade122 of the GA bulge is stacked into the helix and the base of Gua121 is flipped out. The flanking base pairs are tilted open toward the GA bulge, resulting in a ~43° bend between the proximal and distal helices (Chen et al., 2006) (Figure 4C). In the complex with p65, the Gua121 and Ade122 nucleotides are completely flipped out of the helix, widening the major groove to accommodate helix α3x which induces a large roll between the flanking base pairs, opening toward the major groove and compressing the minor groove (Figure 4D). This conformational change in TER results in the 105° bend which could bring loop IV and the stem II spatially closer, facilitating TERT binding by bridging two TERT binding sites, i.e. loop IV and the TBE (Robart et al., 2010; Stone et al., 2007). The G-C base pairs that flank the GA bulge interact extensively with helix α3x and may be important for stabilizing the ends of the two helices. Single molecule FRET studies revealed that p65 binding to stem-loop IV brings stem I and loop IV closer together and this compaction is dependent on the GA bulge (Robart et al., 2010; Stone et al., 2007). The structure of p65-C in complex with stem IV reveals the structural basis and details of this conformational change.

Mutations of residues that recognize the GA bulge decrease TER binding

As discussed above, deletion of the C-terminal tail from p65-C1 or p65-C1ΔL1 results in complete loss of TER binding showing that helix α3x is critical. In order to test the importance of residues from the helix α3x in GA bulge recognition and binding, we generated single alanine point mutants of two key residues, Y407A and R465A in p65-C1ΔL2. Substitution of Y407 with alanine would disrupt the stacking interactions of the aromatic ring on Gua121 and dipole-dipole interactions with Ade122 in the GA bulge. ITC titrations results showed that p65-C1ΔL2 Y407A binds S4 with KDs of 374.5±26.6 nM, which is approximately 4 times lower compared to p65-C1ΔL2 (Figure 2E and Table 1). Substitution of R465 with alanine would disrupt hydrogen bonds to both Gua121 and Ade122, and consistent with this p65-C1ΔL2 R465A binds S4 >6 times more weakly (KD 638.6±46.8 nM) compared to p65-C1ΔL2 (Figure 2F and Table 1). These results substantiate the importance of the interactions of these residues for RNA binding revealed in the crystal structure.

Hierarchical assembly of the catalytic core requires the C-terminal tail but not the β2-β3 loop

Since p65 also has N-terminal, La motif, and RRM1 domains that interact with other regions of TER, i.e. stem I and the 3’ end containing the AUUUU-3’ sequence (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Prathapam et al., 2005), we investigated any potential influence of the C-terminal tail (α3x) or the β2-β3 loop on TER binding and hierarchical assembly in the context of full-length p65 (p65-FL) using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). The β2-β3 loop points away from the RNA in the complex (Figure 3A) but could potentially interact with regions of TER outside the minimal binding site. Partial deletion of the β2-β3 loop in p65-FLΔL1 (Δ421–442) did not affect TER binding (KD ~ 0.7 nM vs 0.6 nM for p65-FL), and complete deletion of loop residues in p65-FLΔL2 (Δ413–459) decreased the binding by ~3 fold (KD ~2.0 nM) (Figure 5A–5C). These results are consistent with the results obtained for the interaction of p65 C-terminal domain constructs with S4 (Figure 2A–2C). Therefore the ~3-fold decrease in binding of p65-FLΔL1 with TER or p65-C1ΔL2 with S4 compared to that of wild type p65-FL or p65-C, respectively, can be attributed to the fact that complete deletion of the loop results in a small change in position of the β2 and β3 strands in the free RRM2 rather than the loop playing a role in TER binding. Taken together these results indicate that the β2-β3 loop does not play any detectable role in interaction with TER. In contrast, deletion of C-terminal tail residues 520–542 (p65-FLΔT) results in reduction of binding affinity by >30 fold (KD ~ 20 nM) (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Hierarchical assembly of p65, TERT, and TER.

(A–D) EMSA of TER with various p65-FL variants: (A) p65-FL, (B) p65-FLΔL1, (C), p65-FLΔL2, (D) p65-ΔT. The bands corresponding to the migration of free TER and TER-p65 complexes are marked on right. At higher concentrations of p65-FL, p65-FLΔL1, and p65-FLΔL2 a second band corresponding to a super-shifted p65-TER higher order complex appears (O'Connor and Collins, 2006). (E–H) Stimulation of TERT binding to TER in the presence of p65-FL variants: (E) p65-FL, (F) p65-FLΔL1, (G) p65-FLΔL2, and (H) p65-FLΔT. For each assay TERT-TER interaction was assayed on the same gel (lanes 1–5). TERT (1–516) concentration required to shift half of the p65-TER complexes is denoted using an asterisk. No stimulation of TERT interaction for TER was observed for p65-FLΔT-TER (H). The key identifying the various bands in E–H is shown at right of panel H.

The p65-TER complex stimulates the binding of TERT(1–516) to TER (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Stone et al., 2007). We investigated this hierarchical assembly of p65-TER with TERT by EMSA (O'Connor and Collins, 2006) (Figure 5E–5H). Both p65-FLΔL1:TER and p65-FLΔL2:TER stimulate TERT binding to the same extent as p65-FL:TER complex (Figure 5E–5G). Thus, deletion of the β2-β3 loop not only has little effect on TER binding but also no effect on hierarchical RNP assembly, indicating that its role, if any, likely involves protein-protein interactions in the context of the holoenzyme. In striking contrast, no ternary complex of TERT with p65-FLΔT:TER is observed, indicating that p65-FLΔT:TER does not stimulate TERT binding (Figure 5H). Previous studies had shown that p65 C-terminal domain was necessary and sufficient for hierarchal assembly (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Prathapam et al., 2005). Here we show that deletion of the C-terminal tail (helix α3x) alone abolishes hierarchal assembly, even in the context of the rest of p65. Together with the structure of the p65-C1ΔL2:S4 complex, these results show that cooperative binding of the C-terminal domain β-sheet and helix α3x to the region of TER stem-loop IV containing the GA bulge is required for assembly of the catalytic core.

xRRM, a new RRM specific to genuine La and LARP7 proteins

Tetrahymena telomerase p65 and Euplotes telomerase p43 are members of a family of La-related proteins 7 (LARP7) (Bayfield et al., 2010; Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009), which also includes the human 7SK binding protein hLARP7 (also called PIP7S and HDCMA18) (Diribarne and Bensaude, 2009; He et al., 2008). Genuine La proteins bind to a 3’-terminal oligo(U) tract of three or more nts (UUU-3’OH) (Alfano et al., 2004; Bayfield et al., 2010; Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009; Kotik-Kogan et al., 2008; Teplova et al., 2006; Wolin and Cedervall, 2002), without other known sequence specificity, while the LARP7 family have stronger specificity for other RNA sequences in addition to recognizing the UUU-3’OH. The predicted domain structure of the LARP7 family is similar to genuine La proteins, in that all proteins contain a LAM followed by an RRM1 and usually an RRM2. For p65, only the LAM and RRM1 domains were predicted (Bayfield et al., 2010; Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009).

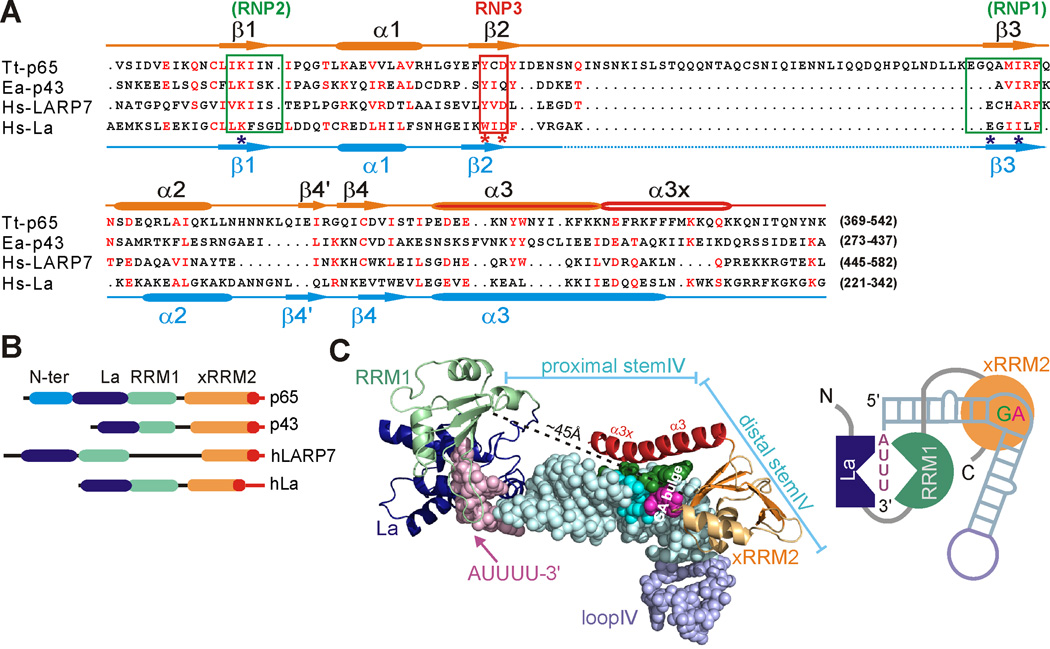

We aligned the sequences of p65 C-terminal domain (RRM2) with the sequences of 33 LARP7 and genuine La family proteins (Figure 6A and Figure S7). The alignment predicts a common atypical RRM with the features found in the structures of p65 (except for the long β2-β3 loop) and hLa protein RRM2 (Jacks et al., 2003), the only other member of this family for which structural data is available, including a C-terminal extension that is unstructured in the free protein. We note that Euplotes p43 does not have a long β2-β3 loop, consistent with the absence of a role for this loop in Tetrahymena telomerase core RNP assembly. The sequence alignment also reveals that the β2 residues that are involved in recognition of Gua121 in the GA bulge are conserved in LARP7 and genuine La proteins, forming a new Aromatic-X-D/E/Q/N motif. The Arg465 on β3, which recognizes both nucleotides in the GA bulge, is also highly conserved (Figure 6A and Figure S7). The decrease in TER binding affinities of p65-C1ΔL2 mutants Y407A (corresponding to the aromatic residue of RNP3 motif) and R465A supports the importance of these residues in RNA interactions (Figure 2E and 2F, and Table 1). The other families of LARP (i.e. LARP1, LARP4, LARP6) (Bayfield et al., 2010; Bousquet-Antonelli and Deragon, 2009) do not share these conserved features in RRM2. In addition, the p65 xRRM2 structure and biochemical studies reported here reveal that one of the conserved features of genuine La proteins, an intrinsically disordered C-terminus (Alfano et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2004; Jacks et al., 2003; Kucera et al., 2011) is common to the LARP7 family as well (Figure 6A and 6B). We suggest naming this domain xRRM for atypical RRM with C-terminal extension and identifying the recognition motif on β2 as RNP3. Similar to RNP1 and RNP2 on the canonical RRMs, RNP3 could recognize diverse nucleotides (Allain et al., 2000; Clery et al., 2008).

Figure 6. La and LARP7 proteins have a common RRM2 structure.

(A) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal region of three LARP7 family proteins Tetrahymena telomerase p65 (Tt-p65), Euplotes telomerase p43 (Ea-p43), human 7SK protein hLARP7 (Hs-LARP7), and human genuine La family protein, hLa (Hs-La). Secondary structure elements of p65 and hLa protein are shown above (orange and red) and below (blue) the sequence, respectively. The atypical RNP1 and RNP2 are boxed in green with positions where conserved aromatic residues in typical RNPs would be marked with *. A conserved RNA binding motif on β2 identified in this study is labeled RNP3 and boxed in red. (B) Domain architecture of p65, p43, hLARP7, and hLa. (C) Model of the interaction of the LAM, RRM1, and xRRM2 domains of p65 on stem-loop IV. LAM and RRM1 domains are based on homology modeling with the crystal structure of hLa LAM and RRM1 complex with UUUA (PDB ID 2VOP) and loop IV is from PDB ID 2H2X. A schematic of the interactions is shown on right. For description of the model building, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Genuine La proteins bind the 3’ UUUOH of newly synthesized Pol III and some Pol II non-coding RNA transcripts with the LAM and RRM1 domains, protecting them from degradation (Bayfield and Maraia, 2009; Kotik-Kogan et al., 2008; Teplova et al., 2006; Wolin and Cedervall, 2002). La proteins also function as RNA chaperones for correct folding of diverse RNAs such as some tRNAs, snRNAs, snoRNAs, and mRNA structural elements (Kucera et al., 2011; Wolin and Cedervall, 2002). The C-terminal region of genuine La proteins is highly divergent with limited sequence similarity. In human La protein the C-terminal tail harbors several functionally important elements such as phosphorylation sites, nuclear localization signal (NLS) and nuclear retention element (NRE) (Bayfield et al., 2010). Several studies have implicated RRM2 and the C-terminal tail of human La protein as important for cellular mRNA translation and critical for HCV virus RNA translation (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2004), but identification of a role for RNA binding by the La RRM2 has been elusive, as exemplified by the structural study of Jacks, et al (Jacks et al., 2003) which failed to show RNA binding. Because the helix α3 occludes the region on the β-sheet surface where single-strand nucleotides usually bind, it has been assumed that single-strand nucleotides would not bind on the β-sheet (Jacks et al., 2003). Very recently it has been reported that RRM2 of human La cooperates with LAM and RRM1 to interact with IRES domain IV of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA (Martino et al., 2012). In S. cerevisiae La, Lhp1p, the C-terminus (which follows its single RRM) is required for accumulation and/or correct folding of certain noncoding RNA precursors, and there is evidence that it becomes structured on binding RNA targets (Kucera et al., 2011). Our results unambiguously show that an xRRM can bind RNA specifically with high affinity. We propose that the homologous xRRM2s in other LARP7 and genuine La proteins interact with structured RNAs in a similar manner to p65, with the atypical RRM providing a binding site for nucleotides in loops and the intrinsically disordered C-terminal tail forming a helix (α3x) that binds the major groove of dsRNA near the loop. Thus the structure of the p65 C-terminal domain-TER complex reveals a new mode for RNA recognition combining ssRNA and dsRNA binding by a new class of RRM that appears to be unique to genuine La and LARP7 proteins. This mode of binding may be general to the chaperone function of genuine La and LARP7 proteins, potentially explaining how xRRM2 would function in the biogenesis of various RNAs (Alfano et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2004; Jacks et al., 2003; Kucera et al., 2011; Martino et al., 2012).

Model of assembly of p65 with TER

The structure of p65 xRRM2 in complex with RNA is the first structure of a telomerase-specific protein in complex with TER and explains why this domain is sufficient to direct hierarchical assembly of the catalytic core in vitro, as it induces an essential conformational change in stem IV required for efficient TERT binding. Based on our present study and the structural homology of p65 with genuine La and LARP7 family proteins we propose that the p65 LAM and RRM1 domains could function in the early steps of telomerase holoenzyme biogenesis in a manner similar to genuine La proteins, cooperatively binding to TER UUU3’OH after it is transcribed by Pol III. Since the Tetrahymena TER UUU3’OH is not subsequently degraded, the LAM+RRM1 would remain associated with TER, positioning xRRM2 to bind to the adjacent proximal stemloop IV and GA bulge, as modeled in Figure 6C. In the folded secondary structure of ciliate TERs, stem I brings the 5’ end of TER close to the 3’ end. A model consistent with the accumulated data is that the N-terminal domain of p65 binds to the 5’ end and/or stem I of TER and the LAM and RRM1 bind to the 3’ end, to help correctly fold stem I and stem-loop IV. Thus, p65 plays at least three essential roles in telomerase biogenesis: first, it protects the 3’ end of TER from degradation; second, it acts as a chaperone to correctly fold TER for protein binding; and third it bends TER stem-loop IV to position it for interaction of loop IV with TERT RNA binding domain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein and RNA preparation

p65 constructs used in these studies were cloned and expressed in E. coli and purified by standard methods as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. TERT(1–516) was purified as described (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Stone et al., 2007). RNAs used in this study were prepared by in vitro transcription and purified by as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

NMR spectroscopy and structure calculations

NMR protein samples were concentrated to 0.8–1.2 mM in 20 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0), containing 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM 1,4-DL-dithiothreitol and 0.02% NaN3 (in 90% H2O/10% D2O). NMR experiments were performed at 298 K on 800 MHz and 500 MHz spectrometers equipped with HCN cryoprobes. Backbone and side-chain assignments of p65-C2 and p65-C2ΔL1 were obtained using a combination of standard triple resonance experiments (Cavanagh et al., 2006). Further details on NMR data acquisition including RDCs and heteronuclear NOE measurements, and resonance and NOE assignments are given in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

The RNA binding to the various constructs of p65 C-terminal domain was characterized by monitoring chemical shift changes in 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 0.2 mM 15N-labeled protein when various TER RNAs were added stepwise up to 0.6 or 0.8 mM (Supplemental Figure S4).

The structure of p65-C2ΔL1 was calculated in a semi-automated iterative manner with the program CYANA 2.1 (Guntert, 2004). A few manually assigned NOEs and chemical shift assignments were supplied to CYANA 2.1 and using 100 starting conformers CYANA 2.1 protocol was applied to calibrate and assign further NOE cross-peaks. Dihedral angle restraints were generated using TALOS+ and were also added to the calculation (Shen et al., 2009). After the first few rounds of automatic calculations, the NOESY spectra were analyzed again to identify additional cross-peaks consistent with the structural model and to correct misidentified NOEs. Slowly exchanging amides involved in hydrogen bonds were identified by re-dissolving the lyophilized protein in 100% 2H2O and collecting 1H-15N HSQC spectra at various time intervals. Hydrogen-bond constraints were then added to the structure calculation protocol. The distance constraints from the twenty conformers with lowest target energy functions (final average target function 3.12±0.24) were converted to XPLOR format using h20refine.py script (Jung et al., 2005; Linge et al., 2003). The final 200 structures were calculated in XPLOR following a standard protocol with incorporation of RDCs. Structures were validated by PROCHECK-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996) and visualized by and PyMol (www.pymol.org). The structural statistics are presented in Table S1.

Crystallization and crystal structure calculations

Free p65-C1ΔL2 and p65-C1ΔL2:S4 were crystallized using hanging drop, vapor-diffusion method. Details of crystallization conditions are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Unit cell dimensions and other parameters are given in Table S2. The p65-C1ΔL2:S4 datasets were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at beamline 24-ID-C (NE-CAT). Datasets were collected at three different wavelengths for peak, inflection, and high remote datasets (Table S2). Data was indexed, integrated, and scaled using XDS (Kabsch, 2010). Macromolecular phasing was carried out by HKL2MAP (Pape and Schneider, 2004) using multiple anomalous dispersion (MAD) method. The resulting phases were improved by using the DM program (CCP4, 1994) and used for manual model building in Coot (Adams et al., 2010; Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). Final iterative rounds of model building and refinement were carried out using Coot and PHENIX (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) with TLS refinement (Painter and Merritt, 2006). Final data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics are presented in Table S2. There are two molecules of protein bound to a duplex RNA in the asymmetric unit. The RNA in the crystal forms a duplex with two identical halves with one protein bound to each half. There is a clear electron density for all the RNA molecule and protein have clear density except for the initial His-tag containing 8–9 residues and C-terminal residues (~532–542). The dataset for p65-C1ΔL2 was collected at 2.5 Å at APS beam line 23-ID-D (GM/CA). Data were indexed and integrated using Mosflm (Leslie, 1992). The structure of the free protein was solved by molecular replacement using structure of protein in p65-C1ΔL2:S4 complex using Phaser and Molrep programs in CCP4 suite (CCP4, 1994; McCoy et al., 2007; Potterton et al., 2003; Vagin and Teplyakov, 1997). The resulting model was inspected and finished manually with the program Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). Final iterative rounds of model building and refinement were carried out using Coot and PHENIX (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004; Adams et al., 2010). Final data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics are presented in Table S1. The asymmetric unit contains six molecules of protein. All molecules are similar with the few differences located mostly in the C-terminal region and flexible region from residues 480–488. Most of the models have a clear electron density for all residues except for the N-terminal his-tag (10 residues) and C-terminal residues from 520 to 542. These parts are not discussed in the interpretation of results. Additionally, some side chains with no interpretable electron density were omitted in the final model.

Isothermal calorimetry (ITC) titration

Binding of various p65 C-terminal domain constructs to RNA was measured by ITC using a MicroCal Omega VP-ITC system (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Both RNA and proteins were extensively dialyzed against the NMR buffer. The proteins at concentrations between 150 to 200 µM, were titrated into 5–10 µM RNA at 298 K. Calorimetric data were analyzed with ORIGIN V5.0 (MicroCal). The binding parameters ΔH, association constant K, and n were kept floating during the fits. The average heat change from the last 4 injections was subtracted from the data to account for the heat of dilution.

Electrophoretic mobility shift and catalytic core assembly assays

The EMSA and catalytic core assembly assays were done essentially as described previously (O'Connor and Collins, 2006) with minor modifications. Radiolabeled TER was synthesized in vitro using T7 polymerase and using 32P-UTP and gel purified. For EMSA, 20 µl binding reaction was assembled by mixing ~0.1 nM “body-labeled” 32P-U-labeled RNA, 500 ng yeast tRNA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25 µL of RNAsin (Promega), 5 mM DTT, and protein dilutions in buffer (20 mM Tris base, pH 8, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl). The binding reaction was incubated at room temperature for 30 min followed by gel electrophoresis on a 6% (37.5:1) polyacryalamide gel at 4 °C for 2.5 hrs.

For the catalytic core assembly assays, TER was incubated with various proteins for 30 min at room temperature followed by addition of TERT(1–516). TERT(1–516) contains all of the primary sites of RNA–TERT interaction, but unlike the full-length TERT it can be expressed in a soluble recombinant form (O'Connor and Collins, 2006; Stone et al., 2007). The concentration of proteins used is indicated on Figure 5A–4D. Control reaction with TER and TERT were run alongside on the same gel.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Structure of domains of telomerase specific assembly protein with telomerase RNA

p65 has a cryptic RRM with a disordered tail which becomes structured upon RNA binding

Structural basis of telomerase RNA conformational change for hierarchical assembly

A new class of RNA recognition motif (xRRM) common to genuine La and LARP7 proteins

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NSF and NIH grants to J.F. The authors thank Drs. C.J. Park, R. Peterson and Q. Zhang for help with NMR, K. Stahmer for help in the early stages of this work, M. Zhao for help with X-ray data collection, and the staff members of beamlines ID-24 (NE-CAT) and ID-23 (GM/CA) at APS of Argonne National Laboratory and CCP4 APS School 2011 for help with data collection and analysis. M.S. designed experiments, prepared samples, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; Z.W. helped refine the NMR structure and performed sequence alignment; B.-K.K. helped with NMR structure calculations; A.P. prepared protein and RNA samples; D.C. helped with X-ray data collection and analysis; K.C. provided reagents and edited the paper; and J.F. designed experiments and analyzed data, supervised all aspects of the work, and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Coordinates and restraints for the 20 lowest energy structures of p65 C-terminal domain (p65-C2ΔL1) and coordinates and structure factors for p65 C-terminal domain (p65-C1ΔL2) and p65 C-terminal domain in complex with stem IV RNA (p65-C1ΔL2:S4) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, under accession numbers 2LSL, 4EYT, and 4ERD respectively. Chemical shifts for p65-C2ΔL1 have been deposited in the BioMagResBank, accession number 18435.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures and References, two tables, and seven figures and can be found at www.cell.com/molecular-cell.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mahavir Singh, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

Zhonghua Wang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

Bon-Kyung Koo, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

Anooj Patel, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

Duilio Cascio, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

Kathleen Collins, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-3200, USA.

Juli Feigon, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and the Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569, USA.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigner S, Postberg J, Lipps HJ, Cech TR. The Euplotes La motif protein p43 has properties of a telomerase-specific subunit. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5736–5747. doi: 10.1021/bi034121y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama BM, Loper J, Najarro K, Stone MD. The C-terminal domain of Tetrahymena thermophila telomerase holoenzyme protein p65 induces multiple structural changes in telomerase RNA. RNA. 2012;18:653–660. doi: 10.1261/rna.031377.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano C, Sanfelice D, Babon J, Kelly G, Jacks A, Curry S, Conte MR. Structural analysis of cooperative RNA binding by the La motif and central RRM domain of human La protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nsmb747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allain FH, Bouvet P, Dieckmann T, Feigon J. Molecular basis of sequence-specific recognition of pre-ribosomal RNA by nucleolin. EMBO J. 2000;19:6870–6881. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allain FH, Gubser CC, Howe PW, Nagai K, Neuhaus D, Varani G. Specificity of ribonucleoprotein interaction determined by RNA folding during complex formulation. Nature. 1996;380:646–650. doi: 10.1038/380646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artandi SE, DePinho RA. Telomeres and telomerase in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:9–18. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autexier C, Lue NF. The structure and function of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:493–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste JL, Mao H, Rao NS, Tan R, Muhandiram DR, Kay LE, Frankel AD, Williamson JR. Alpha helix-RNA major groove recognition in an HIV-1 rev peptide-RRE RNA complex. Science. 1996;273:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayfield MA, Maraia RJ. Precursor-product discrimination by La protein during tRNA metabolism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:430–437. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayfield MA, Yang R, Maraia RJ. Conserved and divergent features of the structure and function of La and La-related proteins (LARPs) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AJ, Gooding AR, Cech TR. Tetrahymena telomerase protein p65 induces conformational changes throughout telomerase RNA (TER) and rescues telomerase reverse transcriptase and TER assembly mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4965–4976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00827-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuch AA, Lundblad V. The maintenance and masking of chromosome termini. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Collins K. Telomerase: An RNP Enzyme Synthesizes DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Antonelli C, Deragon JM. A comprehensive analysis of the La-motif protein superfamily. RNA. 2009;15:750–764. doi: 10.1261/rna.1478709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Skelton NJ, Rance M, Palmer IAG. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Science; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- CCP4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Greider CW. Telomerase RNA structure and function: implications for dyskeratosis congenita. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Fender J, Legassie JD, Jarstfer MB, Bryan TM, Varani G. Structure of stem-loop IV of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA. EMBO J. 2006;25:3156–3166. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clery A, Blatter M, Allain FH. RNA recognition motifs: boring? Not quite. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Svitkin Y, Sonenberg N. La autoantigen is necessary for optimal function of the poliovirus and hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6861–6870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6861-6870.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham DD, Collins K. Biological and biochemical functions of RNA in the tetrahymena telomerase holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4442–4454. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4442-4454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diribarne G, Bensaude O. 7SK RNA a non-coding RNA regulating P-TEFb, a general transcription factor. RNA Biol. 2009;6:122–128. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.2.8115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, Chakshusmathi G, Wolin SL, Reinisch KM. Structure of the La motif: a winged helix domain mediates RNA binding via a conserved aromatic patch. EMBO J. 2004;23:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert P. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:353–378. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He N, Jahchan NS, Hong E, Li Q, Bayfield MA, Maraia RJ, Luo K, Zhou Q. A La-related protein modulates 7SK snRNP integrity to suppress P-TEFb-dependent transcriptional elongation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2008;29:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks A, Babon J, Kelly G, Manolaridis I, Cary PD, Curry S, Conte MR. Structure of the C-terminal domain of human La protein reveals a novel RNA recognition motif coupled to a helical nuclear retention element. Structure. 2003;11:833–843. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JW, Yee A, Wu B, Arrowsmith CH, Lee W. Solution structure of YKR049C, a putative redox protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;38:550–554. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2005.38.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotik-Kogan O, Valentine ER, Sanfelice D, Conte MR, Curry S. Structural analysis reveals conformational plasticity in the recognition of RNA 3' ends by the human La protein. Structure. 2008;16:852–862. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera NJ, Hodsdon ME, Wolin SL. An intrinsically disordered C terminus allows the La protein to assist the biogenesis of diverse noncoding RNA precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1308–1313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017085108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery R, Sklenar H. The definition of generalized helicoidal parameters and of axis curvature for irregular nucleic acids. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1988;6:63–91. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1988.10506483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AGW. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk CA, Bonvin AM, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50:496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J, Hughes TR, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech TR. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Tumasz S, Richie AC, Clos LJ, 2nd, Brow DA, Butcher SE. A novel occluded RNA recognition motif in Prp24 unwinds the U6 RNA internal stem loop. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino L, Pennell S, Kelly G, Bui TT, Kotik-Kogan O, Smerdon SJ, Drake AF, Curry S, Conte MR. Analysis of the interaction with the hepatitis C virus mRNA reveals an alternative mode of RNA recognition by the human La protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Schuller A, Skordalakes E. Telomerase structure function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Collins K. An RPA-related sequence-specific DNA-binding subunit of telomerase holoenzyme is required for elongation processivity and telomere maintenance. Mol Cell. 2009;36:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Collins K. Multiple mechanisms for elongation processivity within the reconstituted tetrahymena telomerase holoenzyme. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16434–16443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor CM, Collins K. A novel RNA binding domain in tetrahymena telomerase p65 initiates hierarchical assembly of telomerase holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2029–2036. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2029-2036.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oubridge C, Ito N, Evans PR, Teo CH, Nagai K. Crystal structure at 1.92 A resolution of the RNA-binding domain of the U1A spliceosomal protein complexed with an RNA hairpin. Nature. 1994;372:432–438. doi: 10.1038/372432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape T, Schneider TR. HKL2MAP: a graphical user interface for macromolecular phasing with SHELX programs. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2004;37:843–844. [Google Scholar]

- Podlevsky JD, Chen JJ. It all comes together at the ends: Telomerase structure, function, and biogenesis. Mutat Res. 2012;730:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prathapam R, Witkin KL, O'Connor CM, Collins K. A telomerase holoenzyme protein enhances telomerase RNA assembly with telomerase reverse transcriptase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:252–257. doi: 10.1038/nsmb900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RJ, Wu H, Trantirek L, O'Connor CM, Collins K, Feigon J. Structural study of elements of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA stem-loop IV domain important for function. RNA. 2006;12:1475–1485. doi: 10.1261/rna.112306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robart AR, O'Connor CM, Collins K. Ciliate telomerase RNA loop IV nucleotides promote hierarchical RNP assembly and holoenzyme stability. RNA. 2010;16:563–571. doi: 10.1261/rna.1936410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Wright WE. Role of telomeres and telomerase in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone MD, Mihalusova M, O'Connor CM, Prathapam R, Collins K, Zhuang X. Stepwise protein-mediated RNA folding directs assembly of telomerase ribonucleoprotein. Nature. 2007;446:458–461. doi: 10.1038/nature05600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplova M, Yuan YR, Phan AT, Malinina L, Ilin S, Teplov A, Patel DJ. Structural basis for recognition and sequestration of UUU(OH) 3' temini of nascent RNA polymerase III transcripts by La, a rheumatic disease autoantigen. Mol Cell. 2006;21:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theimer CA, Feigon J. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani L, Gunderson SI, Mattaj IW, Kay LE, Neuhaus D, Varani G. The NMR structure of the 38 kDa U1A protein - PIE RNA complex reveals the basis of cooperativity in regulation of polyadenylation by human U1A protein. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:329–335. doi: 10.1038/74101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walne AJ, Dokal I. Advances in the understanding of dyskeratosis congenita. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:164–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin KL, Collins K. Holoenzyme proteins required for the physiological assembly and activity of telomerase. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1107–1118. doi: 10.1101/gad.1201704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SL, Cedervall T. The La protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:375–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.150003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JM, Collins K. Telomere maintenance and disease. Lancet. 2003;362:983–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Kim NK, Feigon J. Telomerase and Retrotransposons: Reverse Transcriptases That Shaped Genomes Special Feature Sackler Colloquium: Architecture of human telomerase RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100269109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.