Abstract

Purpose

Mutation of the autophagy gene FYVE (named after the four cysteine-rich proteins: Fab 1 [yeast orthologue of PIKfyve], YOTB, Vac 1 [vesicle transport protein], and EEA1) and coiled coil containing 1 (fyco1) causes human cataract suggesting a role for autophagy in lens function. Here, we analyzed the range and spatial expression patterns of lens autophagy genes and we evaluated whether autophagy could be induced in lens cells exposed to stress.

Methods

Autophagy gene expression levels and their spatial distribution patterns were evaluated between microdissected human lens epithelium and fibers at the mRNA and protein levels by microarray data analysis, real-time PCR and western blot analysis. Selected autophagy protein spatial expression patterns were also examined in newborn mouse lenses by immunohistochemistry. The autophagosomal content of cultured human lens epithelial cells was determined by counting the number of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B)-positive puncta in cells cultured in the presence or absence of serum.

Results

A total of 42 autophagy genes were detected as being expressed by human lens epithelium and fibers. The autophagosomal markers LC3B and FYCO1 were detected throughout the newborn mouse lens. Consistently, the autophagy active form of LC3B (LC3B II) was detected in microdissected human lens fibers. An increased number of LC3B-positive puncta was detected in cultured lens cells upon serum starvation suggesting induction of autophagy in lens cells under stress conditions.

Conclusions

The data provide evidence that autophagy is an important component for the function of lens epithelial and fiber cells. The data are consistent with the notion that disruption of lens autophagy through mutation or inactivation of specific autophagy proteins could lead to loss of lens resistance to stress and/or loss of lens differentiation resulting in cataract formation.

Introduction

The eye lens is an avascular encapsulated organ whose function is to focus light on to the retina where visual information is translated into nerve signals and ultimately perception of images by the visual cortex of the brain. Disruption of lens transparency as a consequence of developmental defect or damage to lens cells and their components causes cataract formation [1–3] which is opacity of the eye lens and is the leading cause of world blindness [4]. The lens contains only a layer of cuboidal undifferentiated epithelial cells on top of a layer of elongated and differentiated lens fiber cells [5]. Lens fiber cells and their components are not renewed and must remain intact to maintain lens transparency throughout the life of the organism. The lens is exposed to photo-oxidative and other environmental damage making the lens an excellent model to study how environmental and oxidative stresses cause cellular and intercellular damage associated with aging [3,6–8]. The lens grows throughout the life of the organism through the slow differentiation of lens epithelial cells into lens fiber cells, which also makes the lens an excellent model for understanding those events important for cellular differentiation and longevity. Damage to the lens and its protein components results in cataract formation [3,7–9]. The differentiation of lens epithelial cells into mature lens fiber cells is accompanied by the degradation of mitochondria, nuclei and other organelles [5]. Failure of lens cells to complete the differentiation process can result in aberrant lens cell structure and inherited cataract formation [10]. Cataract also occurs as a consequence of environmental damage to lens cells and their components as a result of inadequate functioning of protective and repair mechanisms [3,9].

One intriguing system that may be important for lens differentiation and resistance to environmental damage is macroautophagy (hereafter termed autophagy) which operates in the degradation and recycling of damaged organelles and proteins in many other tissues [11]. Autophagy is characterized by the formation of autophagosomes which are double-membrane structures that engulf damaged cellular components and traffic them to lysosomes where the components are degraded/recycled [11–13]. Autophagy has been shown to be important for development [14], aging [15,16], and neurodegeneration [17,18]. Mitophagy, a specialized form of autophagy is a selective process whereby damaged mitochondria are specifically degraded in cells [19,20]. Both autophagy and mitophagy could be important for the removal of damaged lens cells, proteins and organelles. Loss of autophagy and/or mitophagy could, therefore, result in cataract formation.

To date, autophagy has not been extensively studied in the lens. Although autophagic vesicles containing mitochondria and other components were detected by electron microscopy as early as 1984 [21,22] the only paper to address autophagy in the lens reported that, deletion of the autophagy induction gene autophagy related 5 (ATG5) did not disrupt lens fiber cell differentiation despite the occurrence of autophagy in lens cells [23]. Since autophagy is now known to involve ATG5-dependent and ATG5-independent pathways [24] the conclusion that autophagy is not required for lens cell differentiation is no longer supported by the literature.

We have recently demonstrated that mutations in the gene encoding FYVE (named after the four cysteine-rich proteins: Fab 1 [yeast orthologue of PIKfyve], YOTB, Vac 1 [vesicle transport protein], and EEA1) and coiled coil containing 1 (FYCO1) are associated with the inheritance of autosomal recessive human cataract [25] suggesting that autophagy is likely required for the maintenance of lens transparency. FYCO1 is a FYVE and coiled-coil domain containing protein that has been demonstrated to be important for transport of autophagosomes to lysosomes where autophagosomal cargo is degraded [26]. In lens cells, FYCO1 was demonstrated to co-localize with the autophagosomal marker microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B) and lysosomes [25]. Thus FYCO1 could be important for removal of organelles during lens fiber cell differentiation and/or removal of damaged lens proteins.

Based on this study, and the potential importance of autophagy in lens function, we hypothesized that autophagy is important for lens function and resistance to cataract formation. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the spectrum and range of autophagy genes expressed in microdissected human lens epithelium and fibers, we confirmed the mRNA and protein expression levels of functional subsets of autophagy genes in these lens sub-regions, we examined the spatial expression patterns of the autophagosomal marker LC3B and FYCO1 in whole mouse eyes and we monitored numbers of LC3B positive puncta in cultured human lens cells exposed to serum starvation which is a well characterized autophagy inducer in multiple cell types [12].

Our analysis revealed the lens epithelium and fiber expression of 14 genes involved in the induction of autophagy, eight genes involved in expansion and closure of autophagosomes, six genes involved in autophagosome fusion to lysosomes and eight genes involved in specific autophagy sub-pathways including mitophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Consistent with a function for these genes in lens cells, the autophagosomal marker LC3B and the autophagy protein FYCO1 were detected to be present throughout the newborn mouse lens by immunohistochemistry and the active form of LC3B (LC3B II) was detected in microdissected human lens fibers, suggesting that autophagy is an actively occurring process in the lens fibers. Consistently, increased numbers of LC3B-positive puncta were detected in serum-starved lens epithelial cells relative to untreated cells suggesting that autophagy is an important response of the lens to environmental stress. Collectively, these data provide evidence that autophagy is required for lens function and that its disruption could lead to loss of lens stress resistance, loss of lens cell differentiation and ultimately cataract formation.

Methods

Gene expression analysis of specific autophagy transcripts

The levels of autophagy transcripts were analyzed from Affymetrix (U133A) microarray (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) gene signature intensities detected upon hybridization with reverse transcribed and fragmented total lens RNA isolated from pooled microdissected human lens epithelium (7–9 mm central) and fibers (rest of lens; average age 57.8, age range 47–69). These data were previously reported in part [27]. Raw affymetrix chip data were normalized between lens epithelium and fiber cell populations using the housekeeping genes GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phophate dehydrogenase), PGK (phosphoglycerate kinase), and TRP (trieosphate isomerase) as standards. Selected autophagy transcripts were further evaluated by semi-quantitative real-time PCR (RT–PCR) using the SuperScript® III one-step RT–PCR system with Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and GAPDH as control. We assayed 50–100 ng of total RNA from human microdissected lens tissue. RNA was isolated from microdissected human lens epithelium and fiber cells as previously described [28] using the Total RNA kit (Ambion, Woodland, Tx) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A summary of primers used is provided in Table 1. PCR cycle numbers were chosen to be linear at the indicated amounts of RNA and cycle numbers (Table 1).

Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers used in semi-quantitative RT–PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | NCBI# | Cycles | ng RNA | Annealing temp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beclin 1 | CGGGAAGTCGCTGAAGACAG | CCATCCTGGCGAGGAGTTTC | NM_003766.3 | 30 | 100 | 55 |

| atg14 | GAGCGGCGATTTCGTCTACT | CTGAAGACACATCTGCGGGG | NM_014924.4 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| mtor | TTCTGGTGCGACACCGAATC | CATCGGGTTGTAGGCCTGTG | NM_004958.3 | 30 | 100 | 55 |

| rb1cc1/fip200 | GGAGCTTGTGCACCTGAACT | GAAGCACCCTCACCTGGTTTG | NM_014781.4 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| ralb | GCTCGTCGTGGGAAACAAGT | TGACAAAGCAGCCCTTCCAC | NM_002881.2 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| atg4a | GAGTAAGGGCACCTCTGCCTA | GTTCATTCGCTGTGGGGACT | NM_052936.3 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| atg12 | GAGGTCTGTAGTCGCGGAGA | TGGATGGTTCGTGTTCGCTC | NM_004707.3 | 30 | 100 | 55 |

| map1lc3b /atg8 | AAGTGGCTATCGCCAGAGTCG | CTGAGATTGGTGTGGAGACGC | NM_022818.4 | 25 | 100 | 55 |

| rab7 | GACACAGCAGGACAGGAACG | TTGTACAGCTCCACCTCCGT | NM_004637.5 | 25 | 100 | 55 |

| fyco1 | GAAGCTGAAGGCCACCCAAG | GGGCATCTGACTTCTGCCAG | NM_024513.3 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| bnip3l/nix | ACTCGGCTTGTTGTGTTGCT | TCCCTGCTGGTGTGCATTTC | NM_004331.2 | 25 | 100 | 58 |

| pink1 | TCTGCAGTCCTCTGCTCACA | GCTCATCCGTCACTTTCGCT | NM_032409.2 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| p62 | CTCACCGTGAAGGCCTACCT | TAGCGGGTTCCTACCACAGG | NM_003900.4 | 35 | 50 | 55 |

| GAPDH | CCACCCATGGCAAATTCCATGGCA | TCTAGACGGCAGGTCAGGTCCACC | NM_003900.4 | 35 | 50 | 60 |

The corresponding levels of autophagy proteins were further analyzed by western analysis. Protein samples were mixed with 2× Laemmli sample buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, Glycerol 10% [w/v], SDS 0.1% [w/v], 0.0025% Bromophenol Blue, and 5% 2-Mercaptoethanol) at a 1:1 volume ratio and heated at 100 °C for 5 min. Samples were separated by electrophoresis on 8%, 10%, and 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels where appropriate at room temperature using a Bio-Rad mini Protean® vertical electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred onto Hybond™ ECL™ nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) using a Bio-Rad mini Trans Blot® electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad) for 1.5 h at 100 V. Following transfer immunoblots were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.2 for 2 min. Immunoblots were then blocked in 5% milk in Tris Buffered Saline with Tween (TBST; 5% fat-free dry milk, 0.1% Tween-20, 150 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris at pH 7.5) for 1 h before incubation with the appropriate primary antibody diluted in 5% milk TBST (anti-LC3B antibody [Abcam, Cambridge, MA] 1:1,000, anti-RB1CC1/FIP200 [Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX] 1:1,000, anti-FYCO1 [Bethyl laboratories] 1:1,000 and anti-BNIP3L/NIX [Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA] 1:2,000). Blots were washed in TBST and incubated for 1 h with 1:5,000 DyLight goat anti rabbit 800 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) followed by rinsing in PBS pH 7.2 for 2 min. Immunoblots were imaged for 2 min on the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska).

Spatial localization of LC3B and FYCO1 proteins in mouse lens

Animal husbandry and experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved protocol of Animal Institute Committee (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY) and the Association of Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Noon of the day that the vaginal plug was observed was considered as E0.5 of embryogenesis.

Pregnant female mice were euthanized by CO2 and sacrificed following standard procedure. Mouse embryos were dissected and then fixed in 10% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C before paraffin embedding. Serial sections were cut in 5 μm thick sections through the mid-section of the lens. Immunohistological staining was performed following standard procedures described below. Antigen retrieval was performed to unmask the paraffin embedded tissues before antibody incubation.

Whole mouse head sections were processed from a postnatal day 1 (P1) mouse, and LC3B and FYCO1 proteins were visualized by immunohistochemistry using the ImmPRESS Reagent kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cat no. MP-7401; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Briefly, tissues were deparafinized and hydrated using xylene and ethanol gradients and then rinsed in tap water for 5 min. The sections were blocked with 2.5% horse serum for 1 h. Primary FYCO1 (Cat no. A302–796A; rabbit polyclonal; Bethyl Labs) and LC3B antibodies (rabbit polyclonal; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were both diluted in 2.5% horse serum at 1:250, added to the sections and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline contiatween 20 (PBS-T) for 5 min and incubated with the ImmPRESS reagent (Cat no. MP-7401; anti-rabbit immunoglobulin peroxidase, Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 30 min according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sections were washed again in PBS-T and incubated with ImmPACT DAB Peroxidase Substrate (Cat no. SK-4105; Vector Laboratories) for 4 min at room temperature. For the sections that were counterstained, Vector’s Hematoxylin QS (Cat No H-3404) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue sections were incubated with hematoxylin counterstain for 30 s at room temperature and dipped in tap water for 10 s to remove excess stain. Sections were cleared and mounted with VectaMount Permanent Mounting Medium (Cat no. H-5000; Vector Laboratories). Identical procedures were performed using only rabbit secondary antibody as a control. Sections were visualized using an Olympus Provis AX70 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) fluorescent microscope and images captured using Magnafire software (Optronics, Goleta, CA).

Lens cell culture

A human lens epithelial cell line (HLEB3) [29] (a gift from Dr. Majorie Lou, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NB) was grown and cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), gentamicin (50 units/ml; Invitrogen), penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mix (50 units/ml; Invitrogen), and amphotericin B (1.25 µg/ml; Invitrogen) at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. For induction of autophagy by serum starvation HLEB3 lens cells were plated in 24 well plates at a density of 50,000 cells per well overnight. For serum starvation, HLEB3 cells were transferred to serum-free media with or without addition of 50 µM chloroquine, an autophagy inhibitor that prevents autophagosome fusion with lysosomes [30], and assessed for autophagy at 24 h post treatment by staining with an LC3B specific antibody and fluorescent confocal microscopy as described below.

LC3B accumulation assays

HLEB3 lens cells were plated onto coverslips and treated as described above for induction of autophagy using serum starvation. Immunofluoresence staining was conducted by fixing cells with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS, blocking with 1% BSA and permeabilizing with 0.25% TritonX-100 in PBS. Following permeabilization, a rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:1,000 was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature at a 1:2,000 dilution. HLEB3 cells were washed three times with PBS and the nucleus counterstained using 300 nM DAPI (Invitrogen) for 2 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS and mounted onto glass slides using ProLong Gold antiFade reagent (Invitrogen). Immunofluoresence staining was visualized with a Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thronwood, NY). LC3B puncta were quantified in at least 50 cells per treatment using the AxioVision 4 software (Zeiss) by manual visual selection of “events” as described below and the mean and standard deviation calculated. Fully rounded intense green staining of LC3B was counted as a single puncta or “event” representing an autophagosome; diffuse staining is believed to be cytoplasmic LC3 I and was not counted as puncta. Data presented is representative of 3 independent experiments. Differences between treatments and controls were determined using Tukey's test following one-way ANOVA. A p-value less than 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Repertoire of autophagy genes expressed by the human lens

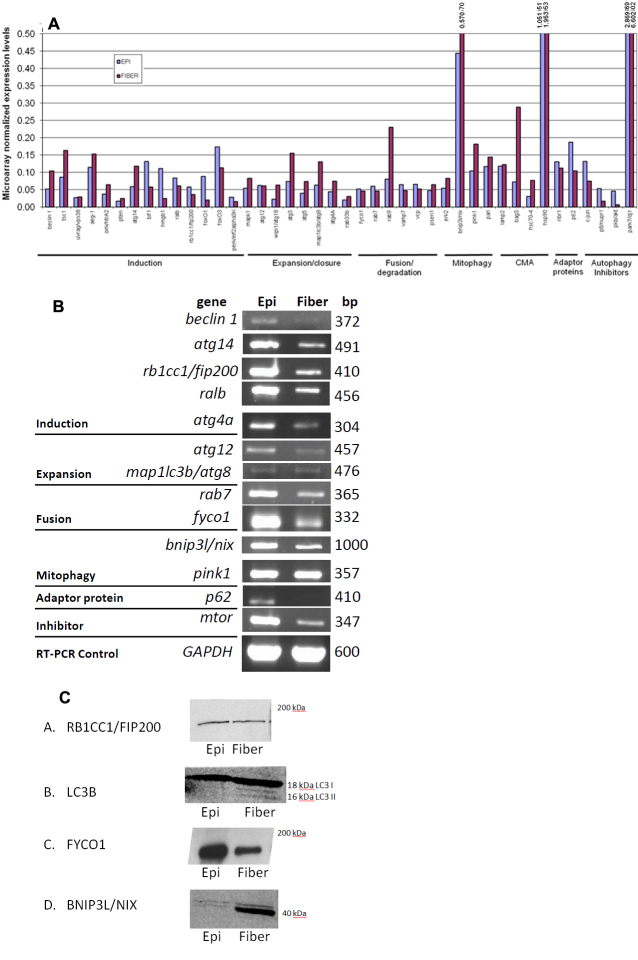

Autophagy-associated gene expression levels were compared between human microdissected lens epithelium (7–9 mm central) and remaining fiber cells through analysis of microarray, semi-quantitative RT–PCR and western blot data. Autophagy-associated transcript levels were first determined through analysis of previously obtained microarray data [27] from 34 pooled human lens epithelium and fiber cell samples (average age 57.8, age range 47–69) analyzed on affymetrix U133A chips. Autophagy gene expression levels were normalized between lens epithelium and fiber cell samples relative to the housekeeping genes GAPDH, PGK, and TRP. This analysis identified the measurable expression in lens epithelium and lens fibers of 42 autophagy-associated genes including autophagy adaptor proteins (proteins involved in linking autophagy components and processes) and autophagy inhibitors. The data are shown in Figure 1A and a summary of the identified genes and their autophagy functions with references is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Expression of autophagy genes in lens epithelium and fibers. A: Histogram representation of microarray gene expression data. Data were normalized to the levels of GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phophate dehydrogenase), PGK (phosphoglycerate kinase), and TRP (trieosphate isomerase). B: Autophagy gene expression in separately isolated human lens epithelium and fiber cells by semi-quantitative RT–PCR. C: Autophagy protein levels of indicated proteins in microdissected human lens epithelium and fiber cells.

Table 2. Identified autophagy genes and their functions.

| Induction | Role in Autophagy | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Beclin 1 | Member of PtdIns 3-kinase complex, involved in activation of macroautophagy | [31] |

| TSC1 | Acts as a gtpase-activating protein for Rheb, thus inhibiting TOR | [32] |

| UVRAG | Member of PtdIns 3-kinase complex, regulates macroautophagy | [33] |

| AEG1 | Gene encodes oncogenic protein that induces macroautophagy independent of Beclin-1 and PtdIns 3-kinase | [34] |

| Omi/HtrA2 | Degrades the Bcl-2 family-related protein Ha × −1 to allow macroautophagy induction | [35] |

| Pten | Dephosphorylates PdtIns(3,4,5)P3 inhibiting PDK1 and PKB/Akt activity | [36,37] |

| Atg14 | Component of PtdIns 3-kinase complex, targets this complex toward autophagic machinery | [38] |

| Bif-1 | Interacts with Beclin 1 via UVRAG and is required for macroautophagy | [39] |

| HMGB1 | Binds beclin-1 to displace Bcl-2 inhibiting apoptosis and promoting macroautophagy | [40] |

| RalB | Activation of phagophore assembly through ULK1-Beclin1-Vps34 complex assembly and Exo84 interaction | [41] |

| RB1CC1/FIP200 | Component of Ulk1 complex, required for phagophore formation, phosphorylation of Ulk1/2 | [42] |

| FoxO1 | Regulates macroautophagy independent of transcriptional control | [43] |

| FoxO3 | Stimulates macroautophagy through transcriptional control of autophagy genes | [44] |

| PERK/eif2α3K | Phosphorylated due to ER stress which induces LC3 conversion and macroautophagy | [45,46] |

| Expansion/Closure | ||

| MAPK1 | MAPK/ERK regulates the maturation of autophagosomes | [47] |

| Atg12 | Ubiquitin-like protein, conjugates Atg5, member of ATG12–5–16 complex, essential for Map1LC3B/Atg8 activation, involved in mitochondrial homeostasis | [48,49] |

| WIPI1/Atg18 | Binds PI3P by WD40 β-propeller domain, involved in retrograde movement of Atg9 | [50,51] |

| Atg3 | E2 ubiquitin ligase, conjugates PE to Map1LC3B after Atg7 processing of c-terminus of cleaved Map1LC3B/Atg8, can be conjugated to Atg12 | [49,52] |

| Atg5 | Contains ubiquitin-folds, member of ATG12–5–16 complex | [48] |

| Map1LC3b/Atg8 | Atg8 homolog, involved in autophagosome biogenesis and cargo recruitment to autophagosomes, marker of autophagosomes | [53–55] |

| Atg4a | Cysteine Protease of Yeast Atg8 homologs, required for Map1LC3B /Atg8 activation, able to deconjugate PE of processed Map1LC3B | [55,56] |

| Rab33B | Binds Atg16L1, involved in autophagosome maturation by regulation of autophagosome to lysosome fusion, OATL1 binding partner | [57,58] |

| Fusion/Degradation | ||

| FYCO1 | Rab7 effector, binds Map1LC3B and phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, coordinates plus-end directed autophagosome transport | [26,59] |

| Rab7 | Transport of early to late endosomes, docking protein for amphisome to lysosome fusion | [26,60–62] |

| Rab9 | Involved in trafficking from late endosomes to the trans-golgi, believed to be a key component of the ATG5/7 alternative macroautophagy pathway | [60,63] |

| VAMP7 | SNARE protein, required for autophagosome formation, autophagosome maturation via facilitation of autophagosome to lysosome fusion | [64,65] |

| VCP | AAA+ ATPase, required for autophagosome maturation, mutations to vcp results in accumulation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes | [66,67] |

| PSEN1 | Protease, part of the γ-secretase complex, involved in lysosomal degradation | [68] |

| Mitophagy | ||

| ERK2 | Localizes to the mitochondria, regulates mitophagy | [69] |

| BNIP3L/NIX | Bcl2 related, necessary for selective mitochondrial clearance | [70] |

| Pink1 | Decreased MMP causes altered Pink1 processing, results in spanning of Pink1 across the outer mitochondrialmembrane, recruiting Parkin for mitophagy | [71] |

| PARL | Mitochondrial protease that regulates PINK1 localization and stability | [72] |

| Chaperone Mediated Autophagy | ||

| Lamp2 | Lysosomal membrane receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy allowing translocation of substrates across the lysosomal membrane. | [73] |

| BAG3 | Directs Hsp70 misfolded protein substrates to dynein targeting them to aggresomes for selective degradation | [74] |

| Hsc70–4 | Aids in targeting of cytosolic proteins to the lysosome for degradation | [75] |

| hsp90 | Assists in LAMP-2A stabilization of during its lateral mobility in the lysosomal membrane | [76] |

| Adaptor Proteins | ||

| NBR1 | Binds ubiquitinated proteins allowing degradation by macroautophagy | [77,78] |

| P62 | Interacts with Atg8 via its LIR domain, adaptor for degradation of ubiquitin-labeled molecules | [78,79] |

| Autophagy Inhibitors | ||

| mTOR | Serine/threonine kinase that controls cells growth and metabolism in response to nutrients, growth factors, cellular energy and stress | [80,81] |

| c-Jun | transcription factor, Inhibits mammalian macroautophagy induced by starvation | [82] |

| p8/Nupr1 | Inhibits macroautophagy by repressing the transcriptional activity of FoxO3 | [83] |

| PKB/Akt | Upstream regulator of mtor | [84] |

| PARK7/DJ1 | Overxpression suppresses macroautophagy through the JNK pathway | [85] |

Of the genes identified in both lens epithelial and lens fiber cells, 14 genes were involved in autophagy induction (Bcl-2 interacting myosin/moesin-like coiled coil protein 1 [beclin 1], tuberous sclerosis complex 1 [tsc 1], UV irradiation resistance-associated gene [uvrag], astrocyte-elevated gene-1 [aeg-1], high temperature requirement factor A2 [omi/htrA2], phosphatase and tensin homolog [pten], autophagy related 14 [atg14], Bax-interacting factor 1 [bif1], high mobility group box 1 [hmgb1], v-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog B [ralB], retinoblastoma 1 inducible coiled coil-1/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family interacting protein of 200 kDa [rb1cc1/fip200], forkhead box O1 [foxO1], forkhead box O3 [foxO3], and PKR-like ER kinase/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3 [perk/eif2alpha3k]), eight genes were involved in expansion of autophagic vesicles (mitogen activated protein kinase 1 [mapk1], autophagy related 12 [atg12], WD repeat domain phosphoinositide-interacting protein 1/autophagy related 18 [wipi1/atg18], autophagy related 3 [atg3], atg5, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B/autophagy related 8 [map1lc3b/atg8], autophagy related 4a [atg4a], and the small GTP-binding protein rab33b), six were genes involved in autophagosome fusion to lysosomes (fyco1, two members of the ras oncogene family; rab7 and rab9, vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 [vamp7], valosin-containing protein/p97 [vcp], and presenilin 1 [psen1]) and eight genes were involved in specific autophagy sub- pathways including mitophagy (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2[erk2], Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein 3-like/NIP3-like protein X [bnip3l/nix], PTEN-induced kinase 1/PARK6 [pink1], and presenilin associated rhomboid-like [parl]) and chaperone mediated autophagy (lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2 [lamp2], Bcl-2-associated athanogene[bag3], heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein 4 [hsc70-4], and heat shock protein 90 [hsp90]; Figure 1A, Table 2).

Of these, the expression levels of 12 autophagy-associated genes were further analyzed by semi-quantitative RT–PCR using a separately prepared RNA sample isolated from a second population of microdissected human lens epithelium and fiber cells (n=5, average age 42.6, age range 15–60; Figure 1B). One additional gene, mammalian target of Rapamycin (mtor), which was present on the microarray but not definitively identified to be expressed, was also analyzed. These genes included the autophagy induction genes beclin 1, atg14, fip200, ralb, the autophagy expansion/closure genes atg4a, atg12, map1lc3b/atg8, the autophagy fusion/degradation genes rab7, fyco1, the mitophagy genes nix/bnip3L, pink1 and the adaptor gene sequestosome 1 (p62). The data confirmed that all of the analyzed genes were expressed in human lens epithelium and fiber cells (Figure 1B). Differences in absolute levels of the genes between microarray and RT–PCR data are consistent with variability in populations of human lenses and differences in techniques used.

Since protein levels of lens autophagy genes could differ from mRNA levels, the protein levels of four selected autophagy genes were also examined in protein extracts isolated from a third pool of separately isolated human lens epithelium and fiber cells (n=34, average age 57.8, age range 47–69; Figure 1C). Consistent with their detection at the mRNA level, autophagy proteins RB1CC1/FIP200, LC3B, and FYCO1 and the mitophagy-associated protein BNIP3L/NIX were detected in both lens epithelium and lens fiber cells. Interestingly, three bands were detected for LC3B in the fiber cells. The 18 kDa band is consistent with the unprocessed cytoplasmic LC3B I [53] while one of the two smaller bands likely represents the activated LC3B – LC3B II at approximately 16 kDa [53,55]. Although we do not know the exact LC3B modification in these two lower molecular weight bands, cytoplasmic LC3B I is known to be cleaved and lipidated during activation leading to a 16 kDa molecular weight band (LC3B II). LC3B II is specifically inserted into the autophagosomal membrane and is, therefore, a classic marker for the presence of autophagosomes [12,55]. Collectively, these data suggest the presence of an autophagy function in both lens epithelium and lens fiber cells.

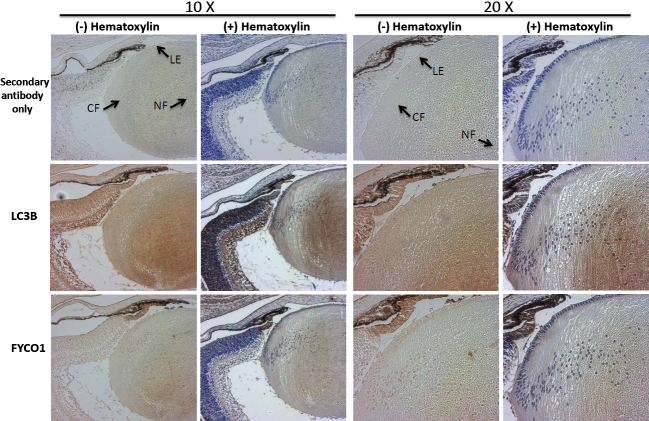

Spatial localization of LC3B and FYCO1 in the mouse eye lens

To determine the localization of some of the autophagy components in the lens and the rest of the eye, day one mouse lenses were sectioned and immunostained with LC3B- and FYCO1-specific antibodies (Figure 2). LC3B is a well characterized marker for autophagosomes [53–55,86,87], and FYCO1 is an autophagy protein associated with cataract [25]. The lens fiber cells consist of cortical fiber cells (CF) that are actively differentiating and still contain mitochondria and nuclei and nuclear fiber cells (NF) which lack nuclei and other organelles and are terminally differentiated. Since our RNA data (above) does not distinguish between cortical and nuclear fibers data using whole lens allows this distinction. The LC3B autophagosomal marker was detected throughout the lens in both lens epithelium and fiber cells although, interestingly, the highest level of LC3B immunoreactivity was detected in the lens nuclear fibers, indicating that autophagy may have played a role in lens fiber cell differentiation. Mouse lens sections were also immunostained with antibody specific to FYCO1 (Figure 2) since its mutation is associated with lens cataract formation [25]. FYCO1 was localized throughout the lens and exhibited a very similar staining pattern to LC3B (Figure 2). The data are consistent with our previous study which demonstrated co-localization of LC3B and FYCO1 in cultured human lens epithelial cells [25].

Figure 2.

Spatial localization of LC3B and FYCO1 in whole mouse lenses. Immunostaining of LC3B and FYCO1 in postnatal day 1 mouse lens with LC3B-specific antibody and FYCO1-specific antibody. Secondary antibody alone is shown as control. Lens epithelium (LE), lens cortical fibers (CF) and nuclear fibers (NF) are indicated. Brown staining show positive antibody cross reactivity and blue hematoxylin staining is nuclear staining.

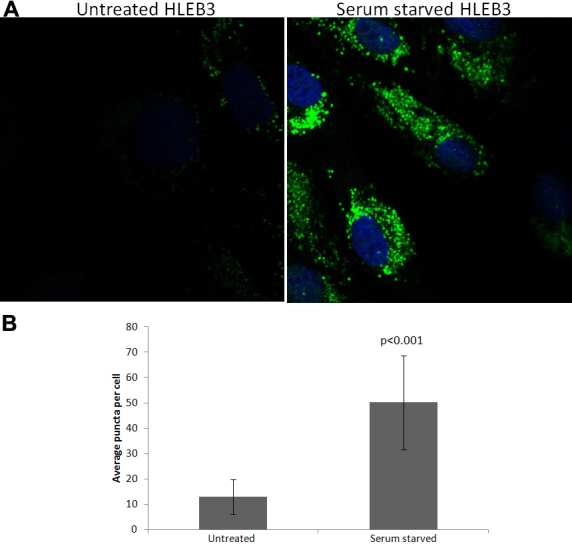

Induction of autophagy in human lens epithelial cells by serum starvation

The detection of expression of multiple autophagy genes in lens epithelium and fibers along with the presence of activated LC3B (LC3B II) in lens fibers suggests that autophagy is a functional process throughout the lens. Since autophagy is a response to stress in many tissues [12] we examined whether it could be induced in lens cells upon serum-starvation. We therefore attempted to detect increased levels of autophagosomes in lens cells by measuring increased numbers of LC3B-positive puncta in cultured human lens epithelial cells exposed to serum starvation and 50 µM chloroquine. Chloroquine is known to prevent autophagosomal fusion with lysosomes allowing visualization of accumulated LC3B II stained autophagosomes that would otherwise be turned over and the signal lost. Human HLEB3 epithelial cells were serum starved for 24 h and levels of LC3B monitored by fluorescent confocal microcopy. Quantitative analysis of LC3B-positive puncta revealed that LC3B-positive puncta numbers increased almost fourfold in lens epithelial cells upon serum starvation and chloroquine addition compared to cells incubated for the same time in complete media with identical chloroquine addition (Figure 3). Statistical analysis of LC3B-positive puncta numbers obtained by direct counting in 50 cells per treatment demonstrated significant differences (p<0.001) in LC3B positive puncta number between untreated control lens epithelial cells and lens epithelial cells exposed to serum-starvation.

Figure 3.

LC3B levels in serum starved human lens epithelial cells. A: LC3B levels in lens epithelial HLEB3 cells exposed to serum starvation and chloroquine (50 µM) detected by immunoflourescent confocal imaging (green). The nucleus is shown by DAPI staining (blue). B: Mean number of LC3B puncta are shown for each treatment (n=50 cells; error bars represent standard deviations). The data are statistically significant at p<0.001 by Tukey analysis.

Discussion

Autophagy has been shown to be important for the development, differentiation and protection against oxidative stress in multiple tissues [14,88], however, to date its role in lens function has remained unexamined. The lens requires the removal of mitochondria and other organelles for fiber cell differentiation and requires multiple protective and repair systems to protect against damage. Since autophagy and mitophagy are critical for these functions in other tissues it is surprising that autophagy and mitophagy have not been explored for their likely role in lens differentiation, lens stress resistance and cataract formation. Recently, it was discovered that mutation of the autophagy gene fyco1 causes human cataract [25], suggesting that autophagy is indeed important for lens differentiation and/or resistance to damage. Consistent with this hypothesis, FYCO1 co-localizes to lysosomes and autophagosomes in cultured lens epithelial cells [25].

As a first step toward examining the potential function of autophagy in the lens, we analyzed the expression levels of autophagy genes in microdissected human lens epithelium and fiber cells. Our analysis revealed the lens epithelium and fiber cell expression of 14 genes involved in autophagy induction, eight genes involved in expansion of autophagy vesicles, six genes involved in autophagosome fusion to lysosomes and eight genes involved in specific autophagy sub-pathways including mitophagy and chaperone mediated autophagy (Figure 1A). The data suggest that all components of the autophagy pathway, including those involved in induction, expansion/closure, and fusion degradation, as well as mitophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy are present and likely functional in lens cells. Since both lens epithelium and fiber cells express these genes they are likely to have functions in both of these lens sub-components. The fiber-preferred expression of some of these genes also provides confidence that their presence in fiber cells is not an artifact of lens epithelial cell contamination or their persistence subsequent to lens cell differentiation. This interpretation is supported by the detection of high levels of LC3B and FYCO1 throughout the newborn mouse lens including lens fibers (Figure 2) and the detection of activated LC3B in the fiber cells by western analysis (Figure 1C). Consistent with an active autophagy pathway in lens cells we detected increased numbers of LC3B-positive puncta and therefore autophagosome number in lens cells exposed to serum starvation which is a well characterized autophagy inducer in a multitude of other studies and cell types (Figure 3). This observation also suggests that autophagy is a response of lens cells to exogenous stress that is likely involved in removing oxidized and aggregated proteins that are known to accumulate in lens cells upon oxidative and other stress conditions.

To date, few reports on the role of autophagy in lens function have been published. Matsui et al. [23] reported that the lenses of mice containing a homozygous knockout of the autophagy inducer ATG5 still developed organelle-free fiber cells, suggesting that this individual autophagy induction pathway was not required for organelle loss during lens cell differentiation. The data did, however, demonstrate that autophagy occurred in the embryonic mouse lens. Recently, Nishida et al. [24] discovered that an alternative, Atg5/7-independent, autophagy pathway operates in conjunction with the ATG5 pathway in non-lens cells to initiate autophagy. The lack of effect of ATG5 deletion on lens fiber cell organelle degradation suggests that the ATG5/7-independent pathway may operate to clear lens organelles during lens cell differentiation. Consistently, two members of the ATG5/7-independent pathway, Rab9 and beclin-1, were detected in both lens epithelium and lens fiber cells in the present study (Figure 1A). Recently Menko and Basu (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, personal communication) reported autophagy was required for degradation of organelles during lens cell differentiation, providing even more evidence that autophagy is indeed involved in lens fiber cell organelle degradation.

In addition to the ATG5 mouse knockout, other knockout mice have been made for some of the genes we detected in the lens but unfortunately no lens or eye phenotype has been described for any of the mice. These include map1lc3b [89], bnip3l/nix [90,91], beclin1 [92], rb1cc1/fip200 [93], bif-1 [39], and lamp2 [94]. Of these, beclin 1 and fip200 were embryonic lethal and atg3 was neonatal lethal. Lamp2 knockout mice were viable but exhibited increased mortality and bif-1, map1LC3b and bnip3l/nix were viable. Only two genes (apart from fyco1) that were identified in the present report have a previously reported lens function; these are fox01 and fox03 [95] which were implicated in lens oxidative stress resistance. Another autophagy gene, not detected in the lens in the present study, called ataxia telangiectasia mutated (atm), has also been reported to be important for lens resistance to cataract [96]. It is intriguing to speculate that the known autophagy functions of these genes could play a role in oxidative stress resistance by lens cells.

In summary, the present data provide evidence for a significant role for autophagy in lens function. Autophagy and mitophagy are likely important for lens cell removal of damaged proteins that could cause cataract upon their accumulation and the degradation of lens organelles during epithelial cell differentiation into fiber cells. Further studies on the role of autophagy in lens resistance to stress and lens cell differentiation are likely to provide additional insight into our understanding of lens development, maintenance and cataract formation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant RO1 EY13022 (M.K.).

References

- 1.Hejtmancik JF, Kantorow M. Molecular genetics of age-related cataract. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andley UP. Effects of alpha-crystallin on lens cell function and cataract pathology. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:887–92. doi: 10.2174/156652409789105598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan LA, McGreal RS, Kantorow M. Oxidative stress defense and repair systems of the ocular lens. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:141–55. doi: 10.2741/365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:4–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414fc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelps-Brown N, Bron A. Lens disorders: A clinical manual of cataract diagnosis. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann (1995) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lou MF. Redox regulation in the lens. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:657–82. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truscott RJ. Age-related nuclear cataract-oxidation is the key. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:709–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinson JA. Oxidative stress in cataracts. Pathophysiology. 2006;13:151–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan LA, Kantorow M. Mitochondrial function and redox control in the aging eye: Role of MsrA and other repair systems in cataract and macular degenerations. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiels A, Hejtmancik JF. Genetic origins of cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:165–73. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravikumar B, Futter M, Jahreiss L, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, Massey DCO, Menzies FM, Narayanan U, Renna M, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Sarkar S, Underwood B, Winslow A, Rubinsztein DC. Mammalian macroautophagy at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1707–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:823–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuervo AM, Bergamini E, Brunk UT, Dröge W, Ffrench M, Terman A. Autophagy and aging; the importance of maintaining “clean” cells. Autophagy. 2005;1:131–40. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.3.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vellai T. Autophagy genes and ageing. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:94–102. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris H, Rubinsztein DC. Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:108–17. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son JH, Shim JH, Kim KH, Ha JY, Han JY. Neuronal autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:89–98. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novak I, Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Zhang J, Wild P, Rozenknop A, Rogov V, Löhr F, Popovic D, Occhipinti A, Reichert AS, Terzic J, Dötsch V, Ney P, Dikic I. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:45–51. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menko AS, Klukas KA, Johnson RG. Chicken embryo lens cultures mimic differentiation in the lens. Dev Biol. 1984;103:129–41. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Porrero JA, Colvée E, Ojeda JL. The mechanisms of cell death and phagocytosis in the early chick lens morphogenesis: a scanning electron microscopy and cytochemical approach. Anat Rec. 1984;208:123–36. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092080113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Kuma A, Ohsumi Y, Mizushima N. Organelle degradation during the lens and erythroid differentiation is independent of autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:485–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, Komatsu M, Otsu K, Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature. 2009;461:654–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Ma Z, Jiao X, Fariss R, Kantorow WL, Kantorow M, Pras E, Frydman M, Pras E, Riazuddin S, Riazuddin SA, Hejtmancik JF. Mutations in FYCO1 cause autosomal-recessive congenital cataracts. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:827–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pankiv S, Alemu EA, Brech A, Bruun JA, Lamark T, Overvatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. FYCO1 is a Rab7 effector that binds to LC3 and PI3P to mediate microtubule plus end-directed vesicle transport. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:253–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawse JR, DeAmicis-Tress C, Cowell TL, Kantorow M. Identification of global gene expression differences between human lens epithelial and cortical fiber cells reveals specific genes and their associated pathways important for specialized lens cell functions. Mol Vis. 2005;11:274–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goswami S, Sheets NL, Zavadil J, Chauhan BK, Erwin P, Reddy VN, Kantorow M, Cvekl A. Spectrum and range of oxidative stress responses of human lens epithelial cells to H2O2 insult. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2084–93. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andley UP, Becker B, Hebert JS, Reddan JR, Morrison AR, Pentland AP. Enhanced prostaglandin synthesis after ultraviolet-B exposure modulates DNA synthesis of lens epithelial cells and lowers intraocular pressure in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:142–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima N, Yoshimorin T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garami A, Zwartkruis FJT, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1457–66. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, Jung JU. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–99. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhutia SK, Kegelman TP, Das SK, Azab B, Su ZZ, Lee SG, Sarkar D, Fisher PB. Astrocyte elevated gene-1 induces protective autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009479107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B, Hu Q, Wang H, Man N, Ren H, Wen L, Nukina N, Fei E, Wang G. Omi/HtrA2 is a positive regulator of autophagy that facilitates the degradation of mutant proteins involved in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1773–84. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arico S, Petiot A, Bauvy C, Dubbelhuis PF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, Ogier-Denis E. The tumor suppressor PTEN positively regulates macroautophagy by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35243–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueno T, Sato W, Horie Y, Komatsu M, Tanida I, Yoshida M, Ohshima S, Mak TW, Watanabe S, Kominami E. Loss of PTEN, a tumor suppressor, causes the strong inhibition of autophagy without affecting LC3 lipidation. Autophagy. 2008;4:692–700. doi: 10.4161/auto.6085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obara K, Ohsumi Y. Atg14: a key player in orchestrating autophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2011;2011:713435. doi: 10.1155/2011/713435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sato Y, Liang C, Hoppe G, Bianchi ME, Tracey KJ, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–51. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang D, Kang R, Livesey KM, Cheh CW, Farkas A, Loughran P, Hoppe G, Bianchi ME, Tracey KJ, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:881–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodemann BO, Orvedahl A, Cheng T, Ram RR, Ou YH, Formstecher E, Maiti M, Hazelett CC, Wauson EM, Camonis JH, Yeaman C, Levine B, White MA. RalB and the exocyst mediate the cellular starvation response by direct activation of autophagosome assembly. Cell. 2011;144:253–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan JL, Mizushima N. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, Yang J, Liao W, Liu X, Zhang H, Wang S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Cytosolic FoxO1 is essential for the induction of autophagy and tumour suppressor activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:665–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kouroku Y, Fujita E, Tanida I, Ueno T, Isoai A, Kumagai H, Ogawa S, Kaufman RJ, Kominami E, Momoi T. ER stress (PERK/eIF2alpha phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:230–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avivar-Valderas A, Salas E, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Nagi C, Debnath J, Aguirre-Ghiso J. PERK integrates autophagy and oxidative stress responses to promote survival during extracellular matrix detachment. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3616–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05164-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corcelle E, Djerbi N, Mari M, Nebout M, Fiorini C, Fénichel P, Hofman P, Poujeol P, Mograbi B. Control of the autophagy maturation step by the MAPK ERK and p38: lessons from environmental carcinogens. Autophagy. 2007;3:57–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD, Klionsky DJ, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395:395–8. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radoshevich L, Murrow L, Chen N, Fernandez E, Roy S, Fung C, Debnath J. ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell death. Cell. 2010;142:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Proikas-Cezanne T, Waddell S, Gaugel A, Frickey T, Lupas A, Nordheim A. WIPI-1alpha (WIPI49), a member of the novel 7-bladed WIPI protein family, is aberrantly expressed in human cancer and is linked to starvation-induced autophagy. Oncogene. 2004;23:9314–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polson HEJ, de Lartigue J, Rigden DJ, Reedijk M, Urbé S, Clague MJ, Tooze S. Mammalian Atg18 (WIPI2) localizes to omegasome-anchored phagophores and positively regulates LC3 lipidation. Autophagy. 2010;6:506–22. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi M, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature. 2000;408:488–92. doi: 10.1038/35044114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidberg H, Shvets E, Shpilka T, Shimron F, Shinder V, Elazar Z. LC3 and GATE-16/GABARAP subfamilies are both essential yet act differently in autophagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 2010;29:1792–802. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Oshitani-Okamoto S, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2805–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li M, Hou Y, Wang J, Chen X, Shao ZM, Yin XM. Kinetics comparisons of mammalian Atg4 homologues indicate selective preferences toward diverse Atg8 substrates. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7327–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Itoh T, Fujita N, Kanno E, Yamamoto A, Yoshimori T, Fukuda M. Golgi-resident small GTPase Rab33B interacts with Atg16L and modulates autophagosome formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2916–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itoh T, Kanno E, Uemura T, Waguri S, Fukuda M. OATL1, a novel autophagosome-resident Rab33B-GAP, regulates autophagosomal maturation. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:839–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pankiv S, Johansen T. FYCO1: Linking autophagosomes to microtubule plus end-directing molecular motors. Autophagy. 2010;6:550–2. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutierrez MG, Munafó DB, Berón W, Colombo MI. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2687–97. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jäger S, Bucci C, Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E, Saftig P, Eskelinen E-L. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4837–48. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riederer MA, Soldati T, Shapiro AD, Lin J, Pfeffer SR. Lysosome biogenesis requires Rab9 function and receptor recycling from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:573–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moreau K, Ravikumar B, Renna M, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagosome precursor maturation requires homotypic fusion. Cell. 2011;146:303–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fader CM, Sánchez DG, Mestre MB, Colombo MI. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 and VAMP3/cellubrevin: two v-SNARE proteins involved in specific steps of the autophagy/multivesicular body pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1901–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ju JS, Fuentealba RA, Miller SE, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Baloh RH, Weihl CC. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:875–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tresse E, Salomons FA, Vesa J, Bott LC, Kimonis V, Yao TP, Dantuma NP, Taylor JP. VCP/p97 is essential for maturation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes and this function is impaired by mutations that cause IBMPFD. Autophagy. 2010;6:217–27. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee JH, Yu WH, Kumar A, Lee S, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Wolfe DM, Martinez-Vicente M, Massey AC, Sovak G, Uchiyama Y, Westaway D, Cuervo AM, Nixon R. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell. 2010;141:1146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dagda RK, Zhu J, Kulich SM, Chu CT. Mitochondrially localized ERK2 regulates mitophagy and autophagic cell stress: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Autophagy. 2008;4:770–82. doi: 10.4161/auto.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schweers RL, Zhang J, Randall MS, Loyd MR, Li W, Dorsey FC, Kundu M, Opferman JT, Cleveland JL, Miller JL, Ney P. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708818104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, May J, Tocilescu MA, Liu W, Ko HS, Magrané J, Moore DJ, Dawson VL, Grailhe R, Dawson TM, Li C, Tieu K, Przedborski S. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:378–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi G, Lee JR, Grimes D, Racacho L, Ye D, Yang H, Ross O, Farrer M, McQuibban GA, Bulman DE. Functional alteration of PARL contributes to mitochondrial dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1966–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science. 1996;273:501–3. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gamerdinger M, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Clement AM, Behl C. BAG3 mediates chaperone-based aggresome-targeting and selective autophagy of misfolded proteins. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:149–56. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chiang HL, Terlecky SR, Plant CP, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science. 1989;246:382–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2799391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5747–63. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, Bjørkøy G, Nunn JL, Bruun JA, Shvets E, McEwan DG, Clausen TH, Wild P, Bilusic I, Theurillat J-P, Øvervatn A, Ishii T, Elazar Z, Komatsu M, Dikic I, Johansen T. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lamark T, Kirkin V, Dikic I, Johansen T. NBR1 and p62 as cargo receptors for selective autophagy of ubiquitinated targets. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1986–90. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alers S, Löffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B. AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: crosstalk, shortcuts and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06159-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hall MN. mTOR-what does it do? Transplant Proc. 2008;40(Suppl):S5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yogev O, Goldberg R, Anzi S, Yogev O, Shaulian E. Jun proteins are starvation-regulated inhibitors of autophagy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2318–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kong DK, Georgescu SP, Cano C, Aronovitz MJ, Iovanna JL, Patten RD, Kyriakis JM, Goruppi S. Deficiency of the Transcriptional Regulator p8 Results in Increased Autophagy and Apoptosis, and Causes Impaired Heart Function. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1335–49. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arico S, Petiot A, Bauvy C, Dubbelhuis PF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, Ogier-Denis E. The tumor suppressor PTEN positively regulates macroautophagy by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35243–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ren H, Fu K, Mu C, Li B, Wang D, Wang G. DJ-1, a cancer and Parkinson’s disease associated protein, regulates autophagy through JNK pathway in cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Klionsky DJ, Cuervo AM, Seglen PO. Methods for monitoring autophagy from yeast to human. Autophagy. 2007;3:181–206. doi: 10.4161/auto.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E. Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 2005;1:84–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kiffin R, Bandyopadhyay U, Cuervo AM. Oxidative stress and autophagy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:152–62. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cann GM, Guignabert C, Ying L, Deshpande N, Bekker JM, Wang L, Zhou B, Rabinovitch M. Developmental expression of LC3alpha and beta: absence of fibronectin or autophagy phenotype in LC3beta knockout mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:187–95. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, Wang J. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of ertyhroid cells. Nature. 2008;454:232–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Diwan A, Koesters AG, Odley AM, Pushkaran S, Baines CP, Spike BT, Daria D, Jegga A, Geiger H, Aronow BJ, Molkentin JD, Macleod KF, Kalfa T, Dorn GW. Unrestrained erythroblast development in Nix −/− mice reveals a mechanism for apoptotic modulation of erythropoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6794–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610666104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gan B, Peng X, Nagy T, Alcaraz A, Gu H, Guan JL. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNFalpha and TSC-mTOR signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:121–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tanaka Y, Guhde G, Suter A, Eskelinen EL, Harmann D, Lullmann-Rauch R, Janssen PM, Blanz J, von Figura K, Saftig P. Accumulation of autophagic valuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature. 2000;406:902–6. doi: 10.1038/35022595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li G, Luna C, Navarro ID, Epstein DL, Huang W, Gonzalez P, Challa P. Resveratrol prevention of oxidative stress damage to lens epithelial cell cultures is mediated by forkhead box O activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4395–401. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kleiman NJ, David J, Elliston CD, Hopkins KM, Smilenov LB, Brenner DJ, Worgul BV, Hall EJ, Lieberman HB. Mrad9 and Atm haploinsufficiency enhance spontaneous and X-ray-induced cataractogenesis in mice. Radiat Res. 2007;168:567–73. doi: 10.1667/rr1122.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]