Abstract

Tyrosine phosphorylation plays a fundamental role in many cellular processes including differentiation, growth and insulin signaling. In insulin resistant muscle, aberrant tyrosine phosphorylation of several proteins has been detected. However, due to the low abundance of tyrosine phosphorylation (<1% of total protein phosphorylation), only a few tyrosine phosphorylation sites have been identified in mammalian skeletal muscle to date. Here, we used immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides prior to HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis to improve the discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation in relatively small skeletal muscle biopsies from rats. This resulted in the identification of 87 distinctly localized tyrosine phosphorylation sites in 46 muscle proteins. Among them, 31 appear to be novel. The tyrosine phosphorylated proteins included major enzymes in the glycolytic pathway and glycogen metabolism, sarcomeric proteins, and proteins involved in Ca2+ homeostasis and phosphocreatine resynthesis. Among proteins regulated by insulin, we found tyrosine phosphorylation sites in glycogen synthase, and two of its inhibitors, GSK-3α and DYRK1A. Moreover, tyrosine phosphorylation sites were identified in several MAP kinases and a protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHPTP2. These results provide the largest catalogue of mammalian skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphorylation sites to date and provide novel targets for the investigation of human skeletal muscle phosphoproteins in various disease states.

Keywords: Tyrosine phosphorylation, Rat muscle, Tyrosine immunoprecipitation, HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

1. Introduction

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation plays a key regulatory role in numerous cellular processes such as growth, proliferation, metabolic homeostasis, differentiation and aging [1]. Most tyrosine kinases are tightly negatively regulated, and only activated under specific conditions. This in part explains why tyrosine phosphorylation accounts for less than 1% of the phosphoproteome [1]. Interestingly, the identification of aberrant expression and activity of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in multiple forms of cancer has led to the development of specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy [2, 3]. This emphasizes the importance of investigating tyrosine phosphorylated proteins.

Skeletal muscle has been widely studied to understand the molecular basis for the physiological adaptation to acute exercise, endurance training and sarcopenia, as well as the pathophysiological changes underlying cancer-related muscle wasting, acquired and inherited myopathies, and insulin resistance [4-10]. In skeletal muscle, tyrosine phosphorylation of specific enzymes modulates insulin and growth factor signaling to glucose transport, glycogen synthesis, protein synthesis, and transcriptional activation [7, 9, 11, 12]. Moreover, the use of phosphoepitope-specific antibodies has demonstrated aberrant phosphotyrosine-mediated signaling in skeletal muscle of insulin resistant individuals [7, 13]. However, recent studies of the tyrosine phosphoproteome in different cell types and tissues have revealed hundreds of tyrosine phosphorylation sites, not only in the previously identified signaling proteins, but also in cytoskeletal proteins, proteins involved in RNA metabolism, and glycolytic enzymes [14-18]. This suggests that the prevalence of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in skeletal muscle is currently underestimated, and that tyrosine phosphorylation could be involved in the regulation of various muscle processes, such as excitation-contraction coupling, sarcomeric function, muscle mass, fiber-type composition and mitochondrial function. Consequently, there is a need for appropriate mass spectrometry-based global protein characterization techniques to generate a more comprehensive picture of the role of tyrosine phosphorylation in muscle.

Using strong cation exchange and titanium dioxide for phosphopeptide enrichment followed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, we previously identified 306 phosphorylation sites in human skeletal muscle. However, only 13 tyrosine phosphorylation (pTyr) sites in 9 proteins were detected [19], probably due to the high abundance of cytoskeletal and contractile proteins in skeletal muscle that made it difficult to detect the low abundant tyrosine phosphorylated proteins by common phosphoproteomics [20, 21]. The combination of phosphotyrosine antibody immunoprecipitation with MS/MS-based detection has emerged as a valuable tool to comprehensively study tyrosine phosphorylation [22, 23]. At first, this has been done using antibodies to immunoprecipitate tyrosine phosphorylated proteins from cultured cells [22, 24] but recent reports indicate that immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides, rather than proteins, improves the study of site-specific tyrosine phosphorylation [16, 17, 23, 25-30].

To our knowledge, no large scale study of in vivo tyrosine phosphorylation of mammalian skeletal muscle has yet been reported. In the present study, we therefore analyzed the in vivo tyrosine phosphorylation of rat skeletal muscle by in-solution trypsin digestion of skeletal muscle lysates, followed by phosphopeptide enrichment using immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides and analysis of the resulting peptides by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. This approach resulted in the identification of 87 distinctly localized tyrosine phosphorylation sites in 46 muscle proteins. To our knowledge, these results represent the largest catalog of skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphorylation sites in mammals to date, and provide novel targets for the investigation of skeletal muscle phosphoproteins in response to exercise, sarcopenia, and pathophysiological conditions such as myopathies, cachexia, and insulin resistance.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

The 3 skeletal muscle samples used for the proteomics analyses in this study were obtained from 3 male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) on a regular chow diet (70% carbohydrate, 10% fat, and 20% protein of calories, Research Diets #D12450B, New Brunswick, NJ) with water ad libitum. Rats were 4 weeks of age, weighed 260-428g, and were housed one per cage in a temperature-controlled environment maintained at 21 °C with an artificial 12:12-h light-dark cycle. The animals were anesthetized with a single intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg), and the vastus lateralis muscle biopsy specimen was immediately blotted free of blood, frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Arizona State University.

2.2. Protein isolation

The muscle biopsies (~100 mg) were homogenized while still frozen in an ice-cold buffer (10 μl/mg tissue) consisting of (final concentrations): 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6; 1mM EDTA; 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM Na3VO4; 10 mM NaF; 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 1 mM ammonium molybdate; 250 μM PMSF; 10 μg/ml leupeptin; and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. After homogenized by a polytron homogenizer on maximum speed for 30 sec, the homogenate was cooled on ice for 20 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C; the resulting supernatant containing 5 mg of lysate supernatant proteins (Solution 1) was used for in-solution digestion. The resulting pellet was dissolved by adding 400 μl of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, centrifuged, and 5 mg of the resulting proteins (Solution 2) were used for in-solution digestion. Protein Solution 1 and Solution 2 were processed in parallel during the following steps. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry.

2.3. In-solution trypsin digestion

Solid urea was added into the protein Solution 1 and Solution 2, respectively to a final concentration of 8 M. Proteins were reduced in 10 mM (final concentration) dithiothreitol (DTT), shaken 1 hr at 600 rpm at 55 °C, cooled down to room temperature, and alkylated in 50 mM (final concentration) freshly made iodoacetamide (IDA) at room temperature for 45 min in the dark. The resulting mixture was diluted 8-fold in 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate so that the final concentration of urea and guanidine hydrochloride was lower than 1 M. Proteomics grade Trypsin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added at a trypsin:substrate ratio of 1:200. The digestion was allowed to proceed at 37 °C overnight and was terminated by the addition of 5% formic acid (FA) to adjust the pH value below 4.0. Appropriate amounts of 5% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) and 100% acetonitrile (ACN) were added to achieve final concentration of 0.05% HFBA and 2% ACN. The resulting peptide mixtures were desalted by solid-phase extraction (Sep-Pak C18 1cc cartridge, Waters corporation, Milford, MA) after sample loading in 0.05% HFBA:2% ACN (v/v) and elution with 400 μl of 50 % ACN:1% FA (v/v) and 400 μl of 80%ACN:1%FA (v/v), respectively. The two eluates were combined and the sample volume was reduced to approximately 10 μl by vacuum centrifugation.

2.4. Enrichment of tyrosine phosphopeptides

Immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides (pTyr-IP) was performed using the PhosphoScan® Kit (P-Tyr-100, #7900, purchased from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Briefly, the peptide mixture from the in-solution digestion was mixed with 1.4 ml immunoprecipitation buffer (50mM MOPS, pH 7.2; 10mM sodium phosphate; 50mM NaCl). 40 μl of pTyr-100 antibody beads in 80 μl slurry were added to the resulting solution and the mixture was incubated overnight on a rotator at 4°C. The beads were washed with the immunoprecipitation buffer three times, followed by HPLC-grade water twice. Phosphopeptides were eluted off the beads with 50 μl of 0.15% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) twice. The two eluates were pooled. The resulting peptide mixtures were purified by solid-phase extraction (C18 OMIX C18, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The samples were dried by vacuum centrifugation and dissolved in 4 μl of 0.1% TFA:2%ACN (v/v), followed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

2.5. Mass spectrometry

The entire peptide mixture from in-solution digestion was desalted, subjected to pTyr-IP, and the resulting enriched tyrosine phosphopeptides were desalted as described above, followed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. For Rat #1, an aliquot containing 25% desalted enriched phosphophopeptides from Solution 1 and 2 were analyzed separately by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS 1st, followed by the analysis of the remaining 75% of the desalted phosphopeptides, respectively. For Rat #2 and #3, the entire desalted phosphopeptides from Solution 1 and 2 were analyzed separately by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Therefore, total 8 HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analyses were performed (4 for Rat #1 with 2 for Solution 1 and 2 for solution 2, 2 for Rat #2, and 2 for Rat #3). HPLC-ESI-MS/MS was performed on a hybrid linear ion trap (LTQ)-Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometer (LTQ FT; Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) fitted with a PicoView™ nanospray source (New Objective, Woburn, MA). On-line capillary HPLC was performed using a Paradigm MS4 micro HPLC (Michrom BioResources, Auburn, CA) with a PicoFrit™ column (New Objective; 75 μm i.d., packed with ProteoPep™ II C18 material, 300 Å). HPLC separations were accomplished with a linear gradient of 2 to 27% ACN in 0.1 % FA in 70 min, a hold of 5 min at 27% ACN, followed by a step to 50% ACN, a hold of 5 min, and then a step to 80%, and a hold of 5 min; flow rate, 300 nl/min. A “top-10” data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry approach was utilized to identify peptides in which a full scan spectrum (survey scan) was acquired followed by collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectra of the 10 most abundant ions in the survey scan. The survey scan was acquired using the FTICR mass analyzer in order to obtain high resolution, high mass accuracy data.

2.6. Data analysis and bioinformatics

Tandem mass spectra were extracted from Xcalibur “RAW” files and charge states were assigned using the Extract_MSN script (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA). The fragment mass spectra were then searched against the ipi.RAT.v3.59 database (39,866 entries, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/IPI/) using Mascot Daemon (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.2). The false discovery rate was determined by selecting the option to search the decoy randomized database. Cross-correlation of Mascot search results with X! Tandem was accomplished with Scaffold (Proteome Software, Portland, OR). The search parameters were: 10 ppm mass tolerance for precursor ion masses and 0.5 Da for product ion masses; digestion with trypsin; a maximum of two missed tryptic cleavages; variable modifications of oxidation of methionine and phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine; and fixed modification of carbamidomethylation. Probability assessment of peptide assignments and protein identifications were made through use of Scaffold (version Scaffold_3_00_08, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). Only peptides with ≥ 95% probability were considered. Proteins that contained identical peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped. Multiple isoforms of a protein were reported only if they were differentiated by at least one unique peptide with ≥ 95% probability, based on Scaffold analysis. Phosphorylation sites were located using Scaffold PTM (version 1.0.3, Proteome Software, Portland, OR, USA), a program based on Ascore algorithm [31, 32]. Sites with Ascores ≥ 13 (P ≤ 0.05) were considered confidently localized [31, 32]. Manual inspection of the MS/MS spectra was performed to further confirm the results. If a peptide has 2 or more mono phosphorylated isoforms identified by Scaffold 3 but each site with Ascore <13, manual inspection of the MS/MS spectra was performed to localize the phosphorylation site. If less than 2 unique fragment ions could be detected in the MS/Ms spectrum for each site, these sites will be classified as ambiguous and will be only counted as one site. If a peptide has a serine or threonine phosphorylation site identified, manual inspection of the MS/MS spectra was performed to confirm the phosphorylation site since pTyr-IP was utilized to enrich tyrosine phosphorylated peptides. Tyrosine kinases were predicted with a specificity of 90% using a web tool, KinasePhos (http://kinasephos.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/) [33, 34].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Rat skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphorylation

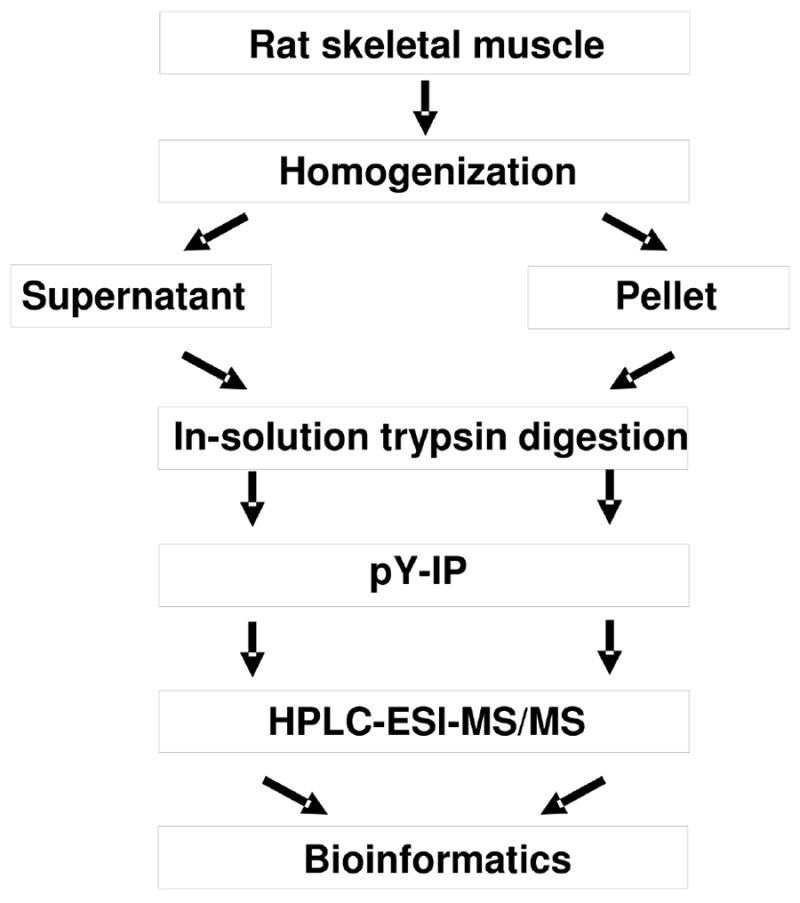

We performed pTyr-IP against tyrosine phosphorylated peptides from 10 mg of skeletal muscle lysates from 3 rats on a regular chow diet (Figure 1). HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis revealed 71, 63, and 77 non-redundant phosphorylation sites (with ≥95% confidence as assessed by Mascot and Scaffold analysis) from rats 1-3, respectively. For each identified phosphopeptide sequence, we have included the following in Supplemental Table 1: modifications, flank residues, precursor mass, charge and mass error observed, and the best Mascot score. Manual inspection of tandem MS spectra was performed to confirm phosphorylation site localization. Total number of distinctly localized pTyr sites from the three rats is 87. In addition, 4 ambiguous tyrosine phosphorylation sites were identified. 16 serine and 9 threonine localized phosphorylation sites were also detected. The phosphoserine/phosphothreonine/phosphotyrosine ratio of the present study was ~2:1:10 compared to ~18:4:1 in our previous work, using phosphopeptide enrichment with SCX and TiO2 to characterize the human skeletal muscle phosphoproteome. These results agree with the literature that pTyr-IP prior to HPLC-ESI-MS/MS is a more efficient approach for tyrosine phosphoproteome studies [16, 17, 23, 25-30].

Figure 1.

Experimental workflow for the analysis of the in vivo phosphoproteome of rat skeletal muscle.

The 87 distinctly localized in vivo pTyr sites were localized in 46 proteins (Table 1). The false discovery rate, as assessed by Mascot searching of a randomized database, was 3% at the peptide level. Table 1 lists the identified isoforms of proteins defined as the ‘canonical’ sequence by UniProtKB/Swiss-prot. Out of the 87 distinctly localized pTyr sites, 56 have been reported in the four large phosphorylation site databases phosphosite.org, phospho.elm.eu.org, www.uniprot.org, and www.phosida.com (Table 1). Thus, 31 pTyr sites appear to be novel. Tandem mass spectra for three sites that were not reported in the 4 phosphorylation sites databases are included as Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 1.

Table 1.

Phosphorylation sites identified in vivo in rat muscle biopsy using pTyr-IP followed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

| Gene | Protein | Phosphorylation Sites |

|---|---|---|

|

Glycolysis

| ||

| FBP2 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 2 | Y216 |

| ALDOA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | Y223 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Y316, Y328 |

| PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Y76, Y196 |

| PGAM2 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 | Y92, Y132*, Y133 |

| ENO1 | α-enolase | Y25, Y44 |

| ENO3 | β-enolase | Y44*, Y131, Y252* |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | Y148 |

| LDHA | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | Y127, Y239 |

|

| ||

| Glycogen metabolism | ||

|

| ||

| GYS1 | Glycogen synthase, muscle | Y44* |

| PYGM | Glycogen phosphorylase, muscle form | Y76*, Y204*, Y227*, Y473, Y525*, Y732*, Y733 |

| PGM1 | Phosphoglucomutase 1 | Y521* |

| GSK3A | Glycogen synthase kinase 3α | Y279, S282 |

| DYRK1A | Dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A | Y321 |

| PHKG1 | Phosphorylase b kinase gamma catalytic chain | Y350* |

|

| ||

| Phosphocreatine shuttle | ||

|

| ||

| CKM | Creatine kinase M-type | Y39*, Y125, Y140*, Y174 |

| CKMT2 | Creatine kinase, sarcomeric mitochondrial precursor | Y368* |

| SLC25A4 | ADP/ATP translocase 1 (ANT1) | Y191, Y195 |

|

| ||

| Ca2+- regulated/binding proteins | ||

|

| ||

| ATP2A1 | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1 | Y15*, Y527 |

| ANXA6 | Annexin A6 | Y609 |

| CASQ1 | Calsequestrin 1 (fragment) | Y9* |

| HRC | Sarcoplasmic reticulum histidine-rich calcium-binding protein | S228*, S378*, S466*, S471*, T476, S549, S550 |

| SRL | Sarcalumenin (98 kDa protein) | Y484* |

|

| ||

| MAP-kinase signaling | ||

|

| ||

| MAPK1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (Erk2) | T183, Y185 |

| MAPK3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (Erk1) | T203, Y205 |

| MAPK12 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 12 (MAP kinase p38 gamma) | T183, Y185 |

| MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MAP kinase p38 α) | T180, Y182 |

| PTPN11 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (SHPTP2) | Y62 |

|

| ||

| Sarcomeric function | ||

|

| ||

| ACTA1 | α-Actin, skeletal muscle | Y55 |

| TPM1 | Tropomyosin 1 | Y162, Y261 |

| TPM2 | Tropomyosin 2 | Y60*, Y162, Y261 |

| MYH1 | Myosin-1 | Y622*, Y1294*, Y1495 |

| MYH2 | Myosin-2 | Y1859 |

| MYH4 | Myosin-4 | Y389, Y424*, Y820*, Y1351*, Y1464, Y1492*, S1495*, Y1856 |

| MYH7 | Myosin-7 | Y410, Y1308*, Y1375, Y1852 |

| MYLPF | Myosin regulatory light chain 2, skeletal muscle | Y158 |

| ACTN3 | α-actinin-3 | Y850* |

| TTN | Titin | Y11721/T11723*, Y18039*, Y18936*, Y21990, Y23841*, Y24117, Y25200, S26266*/Y26267*/T26270*, Y26279, Y28244/T28245*, Y28450*, Y29539*, Y30067*, Y30569*/Y30570*, T32001, S32003 |

|

| ||

| Miscellaneous | ||

|

| ||

| DLG5 | Discs, large homolog 5 | S1367* |

| EEF1A2 | Elongation factor 1- α 2 | Y141, T142 |

| GPR108 | Protein GPR108 | T42* |

| HIPK3 | Homeodomain interacting protein kinase 3 | Y359 |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock cognate 71kDa protein | Y107 |

| LKAP | Limkain-b1 | S71* |

| MDH1 | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic | Y119 |

| PDAP1 | 28 kDa heat-and acid-stable phosphoprotein | S60, S63 |

| PDHA1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit α, somatic form | S293, S300 |

| PRPF4B | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PRP4 homolog | Y849 |

| PXN | Paxillin (64 kDa protein, IPI00363651,IPI00471807) | Y114 |

| RPS27L | 40S ribosomal protein S27-like protein | Y31 |

| STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | Y699 |

| VPS13C | Vacuolar protein sorting 13C protein, isoform 1A | T1434 |

| ----------- | 64 kDa protein, IPI00191437 | S6* |

Ambiguous sites were indicated by “/”.

Novel phosphorylation sites.

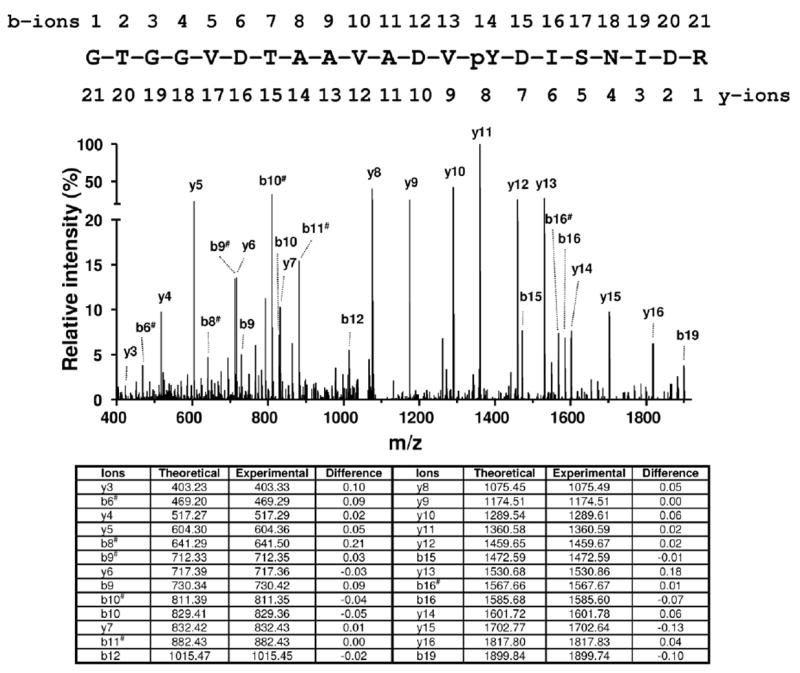

Figure 2.

Representative MS/MS spectrum for a novel phosphorylated peptide 355GTGGVDTAAVADVpYDISNIDR375 of sarcomeric mitochondrial creatine kinase. The ions corresponding to b9, b10, b12 and y5, y6, y7 are consistent with phosphorylation on Tyr368.

It is noted that in total, 942 unique peptides assigned to 182 unique proteins were identified in the experiments, including 794 non-phosphorylated peptides and 148 phosphopeptides. Among the unique phosphopeptides, 129 contain phosphorylated tyrosine residues, which correspond to 87 distinctly localized in vivo pTyr sites localized in 46 proteins as mentioned above.

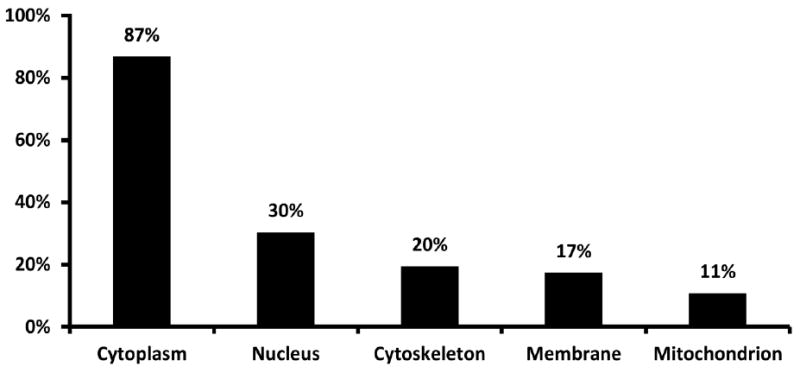

3.2. Gene ontology annotation and functional classification

Gene ontology annotation (GO) and literature search revealed that 39 tyrosine phosphoproteins could be assigned to the cytoplasm, 13 to the nucleus, 8 to the membrane, 8 to the cytoskeleton, and 5 to the mitochondrion (Figure 3). Notably, some proteins can be assigned to multiple GO terms.

Figure 3.

Subcellular location of identified phosphoproteins in rat skeletal muscle based on gene ontology annotation and literature search.

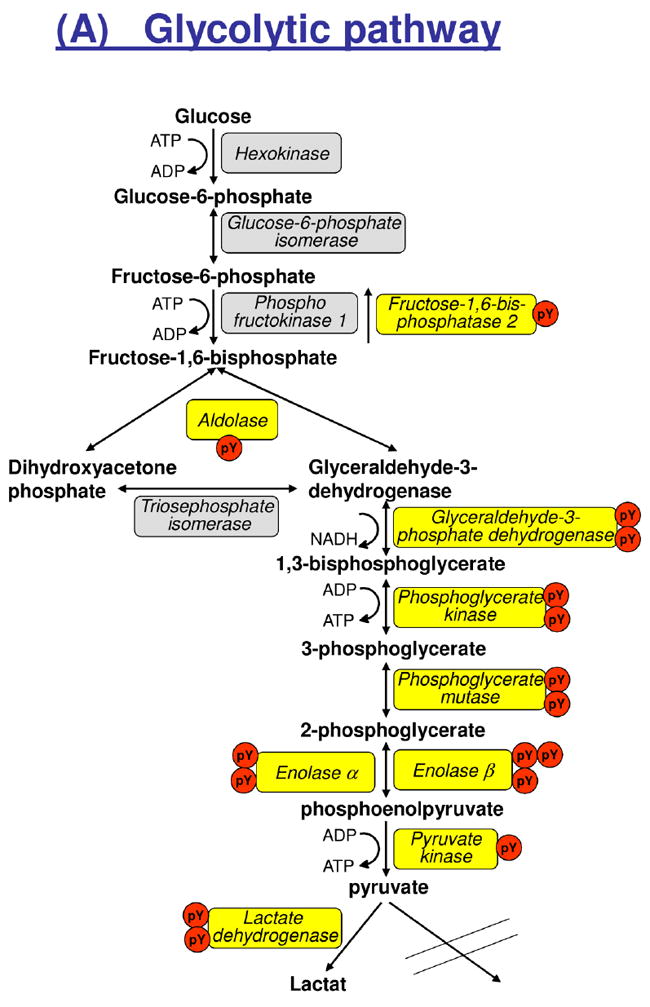

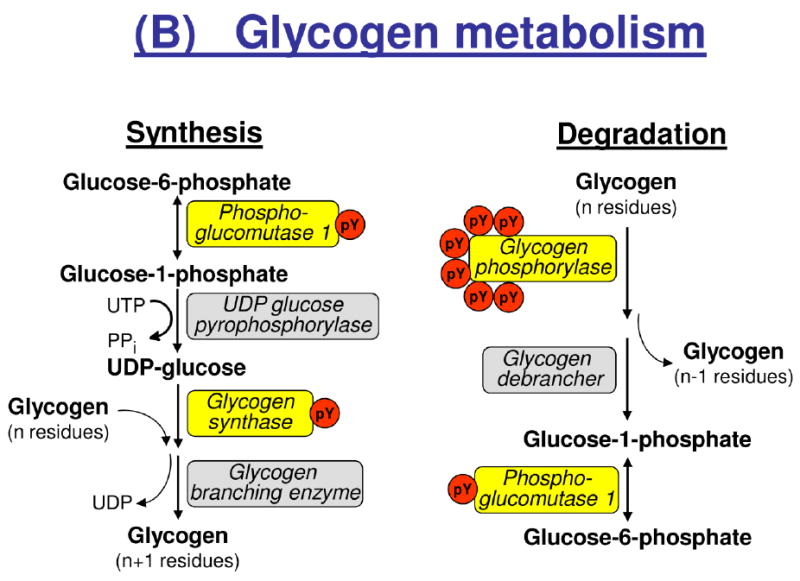

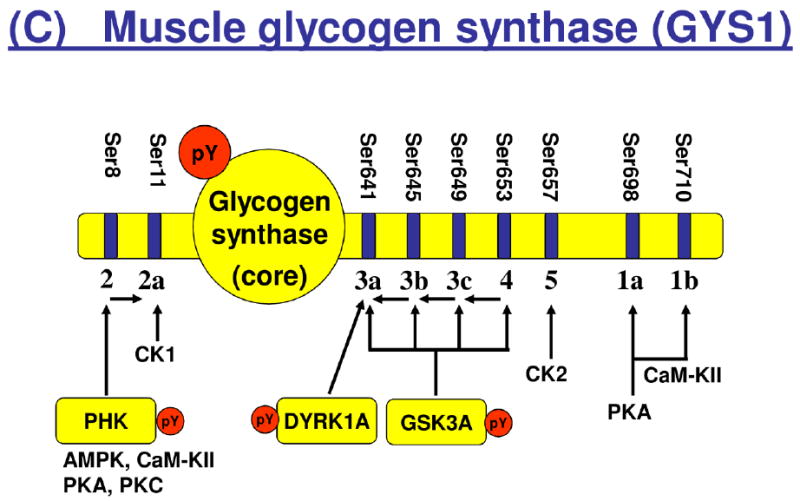

Closer examination of the protein functions revealed that 17 distinctly localized pTyr sites were identified in 8 of 13 major enzymes of the glycolytic pathway, while additional 9 distinctly localized pTyr sites were identified in 3 major enzymes involved in glycogen metabolism and 3 signaling proteins known to regulate these enzymes (Figure 4). Another major part (40%) of the pTyr sites were found in sarcomeric proteins including several sites in the major myosin isoforms in mammalian skeletal muscle and the giant muscle protein, titin. We also identified tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins involved in phosphocreatine resynthesis, Ca2+-homeostasis and MAP kinase signaling. Interestingly, we identified tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5B, which has been shown to regulate skeletal muscle growth [11] (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of enzymes involved in glycolysis and glycogen metabolism. Isoforms and/or subunits of enzymes involved in (A) glycolysis, (B) glycogen metabolism, and (C) regulation of muscle glycogen synthase (GYS1). Tyrosine phosphorylated proteins are shown in yellow boxes, and the number of identified tyrosine phosphorylation sites (pY) are indicated by red circles. Number of serine (Ser) residues on GYS1 indicates known Ser phosphorylation sites with their classical number of site given below the bar. AMPK, AMP-activated kinase; CaM-KII, calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II; CK1, casein kinase 1; CK2, casein kinase 2; DYRK1A, dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A; GSK3A, glycogen synthase kinase a; PHK, phosphorylase kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C.

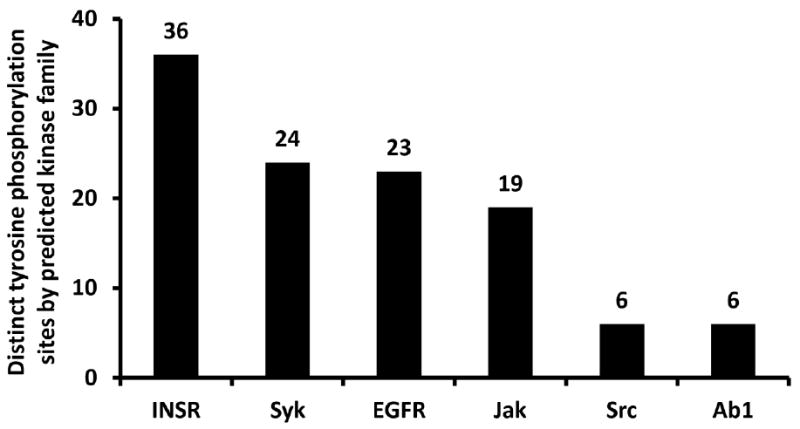

3.3. Potential kinases for identified tyrosine phosphorylation sites

Using KinasePhos [33, 34], we have predicted potential kinases for identified tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Supplemental Table 2). The number of distinct tyrosine phosphorylation sites by predicted kinase family for all phosphoproteins is shown in Figure 5. The potential tyrosine kinases include Insulin receptor (INSR), Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Tyrosine kinase Src (Src), Spleen Tyrosine kinase (Syk), Abelson murine leukemia virus oncoprotein (Ab1). Insulin receptor is the predicted kinase for 37 of the tyrosine sites identified, such as Tyr191 and Tyr195 in ADP/ATP translocase 1, Tyr44 in β-enolase, Tyr39, Tyr125, and Tyr140 in creatine kinase M-type, Tyr141 in elongation factor 1, Tyr44 in glycogen synthase, Tyr699 in Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B. More experiments will be needed to verify whether these kinases indeed have the ability to phosphorylate these phosphorylation sites.

Figure 5.

Number of distinct pY sites by potential kinase family for all phosphoproteins predicted by KinasePhos [33]. Insulin receptor (INSR), Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Tyrosine kinase Src (Src), Spleen Tyrosine kinase (Syk), Abelson murine leukemia virus oncoprotein (Ab1).

4. Discussions

4.1. pTyr-IP and rat skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphoproteome

Elucidating the role of tyrosine protein phosphorylation in normal skeletal muscle and its abnormalities in skeletal muscle disorders has been limited due to insufficient knowledge of protein tyrosine phosphorylation sites. Furthermore, identification of the tyrosine phosphorylation sites in mammalian skeletal muscle in vivo has been challenging due to technical limitations. Using a combination of phosphopeptide enrichment technique, pTyr-IP, with HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, the present study provides the first large-scale tyrosine phosphorylation study of rat skeletal muscle in vivo using 10mg of lysate proteins from relatively small tissue samples, a muscle biopsy of approximately 100 mg wet weight. We identified 87 distinctly localized and 4 ambiguous pTyr sites in 46 proteins from 3 rats. Of these distinctly localized ones, 56 sites have previously been reported in four large protein phosphorylation site databases from various cell lines or species, while 31 appear to be novel. Even though the absolute number of phosphorylation sites identified is low when compared to large-scale phosphoproteomic studies of human cell lines [16, 22-27], it is the first global analysis of pTyr sites in mammalian skeletal muscle. In addition, since estimated tyrosine phosphorylation accounts for less than 1% of the phosphoproteome [1], the finding of 87 pTyr sites in our study suggest that a total of about 8700 phosphorylation sites in rat skeletal muscle.

The majority of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins identified in skeletal muscle were high abundant proteins, such as sarcomeric proteins and enzymes involved in glycolysis, glycogen metabolism, Ca2+-homeostasis and the phosphocreatine shuttle. However, we also identified many known as well as new pTyr sites on low abundant signaling intermediates, such as several MAP kinases, PTPN11, GSK3, DYRK1, STAT5B, and GYS1. This indicates that our phosphopeptide tyrosine immunoprecipitation protocol may be suitable for targeted phosphoproteomic studies of tyrosine phosphorylated signaling events in skeletal muscle, such as in response to insulin stimulation or exercise.

In addition to detecting tyrosine phosphorylation sites, 16 serine and 9 threonine phosphorylation sites were identified. Among the 16 serine phosphorylation sites, 1 was detected in a doubly phosphorylated peptide with both pY279 and pS282 in GSK3A; 9 were detected in double or triple serine/threonine phosphorylated peptides, including HRC (pS466, pS471), HRC (pS466, pS471 and pT476), HRC (S549, S550), PDAP1 (S60, S63), PDHA1 (S293, S300), TTN (T32001, S32003); and 6 were detected in peptides with single phosphorylated serine residues. For the 9 threonine phosphorylation sites, 4 were detected in doubly phosphorylated peptides containing a tyrosine phosphorylation site, including MAPK1 (T183, Y185), MAPK3 (T203, Y205), MAPK12 (T183, Y185), and MAPK14 (T180, Y182); 2 were detected in double or triple serine/threonine phosphorylated peptides, including HRC (pS466, pS471 and pT476) and TTN (T32001, S32003); and 3 were detected in peptides with single phosphorylated threonine residues. These results along with the 794 non-phosphorylated peptides identified in the study indicated that even though pTyr IP is relatively specific, non-specific binding might still present a problem. Nonetheless, in our previous study to characterize human skeletal muscle proteome [35], 7657 unique peptides in 954 proteins were detected from muscle biopsies, while only 4 pTyr sites in 4 proteins were detected. In addition, as discussed before, we previously identified 13 pTyr sites in 9 proteins out of 306 phosphorylation sites in127 proteins in human skeletal muscle [19]. On the other hand, in the present study, 87 pTyr sites were identified in 46 proteins out of 182 proteins, indicating pTyr-IP is an efficient way to enrich tyrosine phosphorylated peptides.

4.2. Tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes

An important finding of the present study is that the majority of glycolytic enzymes are tyrosine phosphorylated in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. Previous reports have demonstrated tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes (gene names: PFKM, ENO, PKM2, PGAM2, LDHA and GAPDH) either in vitro or in vivo in response to activation of tyrosine-specific kinases by growth factors or by transformation of normal cells into cancer cells [16, 36-40]. It has been proposed that tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes is implicated in the switch from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) that is important for cancer cell and tumor growth [40]. This suggests that increased tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes in skeletal muscle could contribute to the decreased ratio between glycolytic and oxidative enzyme activities observed in insulin resistant conditions such as obesity and T2D [41, 42]. Moreover, tyrosine phosphorylation of GAPDH in response to insulin may contribute to the interaction of GAPDH with GLUT4, which has been proposed to regulate the intrinsic activity of GLUT4 [43]. In support of this, it was recently demonstrated that insulin increased tyrosine phosphorylation of GAPDH at Tyr316 and of ENO1/3 at Tyr44 by more than 1.3 fold in human adipocytes [17]. These findings also support the notion that insulin, similar to other growth factors, stimulates glycolysis by tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes. Further studies are needed to establish the role of tyrosine phosphorylation of glycolytic enzymes in metabolic homeostasis in normal and diseased human skeletal muscle.

4.3. Tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen metabolism enzymes

In addition to glycolytic enzymes, we found several pTyr-sites on major enzymes involved in glycogen metabolism, including a phosphorylation site at Tyr44 on muscle glycogen synthase (GYS1) and constitutive activation-loop autophosphorylation of two serine/threonine kinases, GSK3A (Tyr279) and DYRK1A (Tyr321) [44, 45], known to inactivate GYS1 by phosphorylation at specific C-terminal Ser residues [7, 46], respectively. Insulin stimulates GYS1 by dephosphorylation of several serine residues, and this effect is impaired in insulin resistant conditions [46-48]. The Tyr44 residue of GYS1 is located close to the reported UDP-glucose binding site of GYS1 at Lys39 in rat skeletal muscle [49], suggesting that phosphorylation at pTyr44 may modulate the binding between GYS1 and UDP-glucose. It is tempting to speculate that hormonal factors such as insulin as well as muscle contraction may regulate phosphorylation of Tyr44, which will contribute to the regulation of glycogen synthesis. Muscle contraction stimulates phosphorylase kinase which in turn activates glycogen phosphorylase (PYGM) by phosphorylation of Ser15. In the present study, we found a novel pTyr-site at Tyr350 on the catalytic gamma subunit of phosphorylase kinase (PHKG1) and several pTyr-sites on PYGM in rats in the resting, basal state, suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation may contribute to keep these enzymes in an inactive state under these conditions. Further studies are warranted to determine the potential role of these pTyr-sites on enzymes involved in glycogen synthesis and glycogenolysis in response to various physiological stimuli and pathophysiological conditions.

4.4. Tyrosine phosphorylation on mitochondrial proteins

In the present study, we identified three pTyr-sites on two mitochondrial proteins, ADP/ATP translocase 1 (SLC25A4/ANT1) and the mitochondrial creatine kinase (CKMT2) in whole muscle cell lysates using pTyr-IP and MS/MS. Recently, phosphorylation of ANT1 at Tyr195 was suggested to be critical for mitochondrial respiration in rat heart muscle [50] and together with the cytosolic and mitochondrial isoenzymes of creatine kinase (CKM and CKMT2) ANT1 regulate the phosphocreatine/creatine pool in muscle cells by resynthesizing phosphocreatine from mitochondrial ATP synthesis [51]. This suggests that tyrosine phosphorylation of ANT1, CKMT2 and CKM could regulate re-synthesis of ATP after muscle work in mammalian skeletal muscle. In a recent phosphoproteomic study of isolated mitochondria from human skeletal muscle, 16 pTyr-sites on 12 mitochondrial proteins were reported [52]. Consistently, numerous tyrosine phosphorylated mitochondrial proteins have been discovered within the last decade using a variety of proteomic and phosphoproteomic approaches [53, 54]. We therefore assume that a more comprehensive identification of the mitochondrial tyrosine phosphoproteome in mammalian skeletal muscle than that observed by Zhao et al [52] can be acquired by the isolation of mitochondria prior to immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides and subsequent HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

4.5. Tyrosine phosphorylation of sarcomeric proteins

The sarcomere is the basic functional unit in striated muscle contraction. Using the phosphoproteomic approach, we identified 33 distinctly localized pTyr-sites on muscle- and fiber-type specific isoforms of myosins and thin filament proteins (α-actin and tropomyosins), the giant muscle protein, titin, the fast-fiber specific Z-disc protein, α-actinin-3, as well as 5 pTyr-sites on proteins involved in excitation-contraction coupling (the Ca2+-cycle). Information about tyrosine phosphorylation of sarcomeric proteins in adult mammalian skeletal muscle is scarce, but previous studies have suggested that tyrosine phosphorylation of myosin heavy chains is mediated by insulin [55], and may be involved in skeletal muscle differentiation (reorganization) [56]. Here, we report pTyr-sites on all 3 major adult heavy myosin chains (MYH1, MYH2 and MYH7), in resting skeletal muscle. However, further studies are needed to address the potential role of these pTyr-sites, and whether they regulate the actomyosin interaction and myosin ATPase activity in vivo.

4.6. Comparison to pTyr-IP in quantitative phosphoproteomic studies of mouse adipocytes

Recently, Schmelzle et al. [17] studied insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation in mouse adipocytes using a protocol very similar to that in the present study. By combining anti-phosphotyrosine peptide immunoprecipitation and immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) with MS/MS, they reported relative quantification of 122 pTyr-sites on 89 proteins in 3T3-L1 adipocytes stimulated with insulin for 0, 5, 15, and 45 min [17]. Strikingly, several of the same pTyr-sites were identified in our study. This included pTyr-sites showing at least a 3-fold increase in response to insulin such as MAPK3/Erk1 (Tyr205), MAPK1/Erk2 (Tyr185), ENO1/3 (Tyr44), GAPDH (Tyr316), and MAP kinase p38α (Tyr182). In addition, several proteins with pTyr-sites not responding to insulin were identified in both studies including DYRK1A (Ty321), EEF1A2 (Tyr141), GSK3A (Tyr279), HIPK3 (Ty359), PRPF4B/PRP4 (Tyr849), PXN (Tyr118) and SHP-2/PTPN11 (Tyr62). The protein-tyrosine phosphatase 2 (PTPN11) is required for insulin activation of MAPK1/Erk2 by increasing phosphorylation of Thr183 and Tyr185 [57]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that pTyr-IP may be useful in quantitative phosphoproteomic studies of low-abundant enzymes regulated by insulin and growth factor signaling.

5. Conclusions

Using pTyr-IP followed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, we identified 87 distinctly localized (31 novel) in 46 rat skeletal muscle proteins, the largest catalogue of mammalian skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphorylation sites to date. The identified tyrosine phosphorylated proteins includes most major enzymes in the glycolytic pathway, enzymes regulating glycogen metabolism, proteins involved in Ca2+-homeostasis and phosphocreatine re-synthesis, as well as MAP kinases and mitochondrial proteins. These results provide multiple novel protein pTyr-sites for the investigation of human skeletal muscle in conditions of health and disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Identified 87 distinctly localized tyrosine phosphorylation sites (31 were novel) in 46 muscle proteins from a relative small rat muscle biopsies

Demonstrated the feasibility of using immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosine peptides to improve the discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation in muscle

Provide the largest catalogue of mammalian skeletal muscle tyrosine phosphorylation sites to date

Provide novel targets for the investigation of human skeletal muscle phosphoproteins in various disease states

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Clinical/translational Research Award from the American Diabetes Association 7-09-CT-56 (ZY), a Clinical Research Grant from the American Diabetes Association 1-09-CR-39 (CM) and NIH grants R01DK081750 (ZY) and R21DK082820 (CM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hunter T. Tyrosine phosphorylation: thirty years and counting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–65. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amit I, Wides R, Yarden Y. Evolvable signaling networks of receptor tyrosine kinases: relevance of robustness to malignancy and to cancer therapy. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:151. doi: 10.1038/msb4100195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockl KS, Witczak CA, Goodyear LJ. Signaling mechanisms in skeletal muscle: acute responses and chronic adaptations to exercise. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:145–53. doi: 10.1002/iub.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttridge DC. Signaling pathways weigh in on decisions to make or break skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:443–50. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000134364.61406.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiaffino S, Sandri M, Murgia M. Activity-dependent signaling pathways controlling muscle diversity and plasticity. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:269–78. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00009.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hojlund K, Beck-Nielsen H. Impaired glycogen synthase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle: markers or mediators of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2:375–95. doi: 10.2174/1573399810602040375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Molecular mechanisms in aging and current strategies to counteract sarcopenia. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:90–101. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003020090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass DJ. Signaling pathways perturbing muscle mass. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:225–9. doi: 10.1097/mco.0b013e32833862df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahenk Z, Mendell JR. The muscular dystrophies: distinct pathogenic mechanisms invite novel therapeutic approaches. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moller L, Dalman L, Norrelund H, Billestrup N, Frystyk J, Moller N, et al. Impact of fasting on growth hormone signaling and action in muscle and fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:965–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirola L, Johnston AM, Van Obberghen E. Modulation of insulin action. Diabetologia. 2004;47:170–84. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cusi K, Maezono K, Osman A, Pendergrass M, Patti ME, Pratipanawatr T, et al. Insulin resistance differentially affects the PI 3-kinase- and MAP kinase-mediated signaling in human muscle. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:311–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amanchy R, Kalume DE, Iwahori A, Zhong J, Pandey A. Phosphoproteome analysis of HeLa cells using stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1661–71. doi: 10.1021/pr050134h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boersema PJ, Foong LY, Ding VM, Lemeer S, van Breukelen B, Philp R, et al. In-depth qualitative and quantitative profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation using a combination of phosphopeptide immunoaffinity purification and stable isotope dimethyl labeling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:84–99. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900291-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmelzle K, Kane S, Gridley S, Lienhard GE, White FM. Temporal dynamics of tyrosine phosphorylation in insulin signaling. Diabetes. 2006;55:2171–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1488–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hojlund K, Bowen BP, Hwang H, Flynn CR, Madireddy L, Geetha T, et al. In vivo phosphoproteome of human skeletal muscle revealed by phosphopeptide enrichment and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4954–65. doi: 10.1021/pr9007267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi Z, Bowen BP, Hwang H, Jenkinson CP, Coletta DK, Lefort N, et al. Global relationship between the proteome and transcriptome of human skeletal muscle. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3230–41. doi: 10.1021/pr800064s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hojlund K, Yi Z, Hwang H, Bowen B, Lefort N, Flynn CR, et al. Characterization of the human skeletal muscle proteome by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:257–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700304-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blagoev B, Ong SE, Kratchmarova I, Mann M. Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1139–45. doi: 10.1038/nbt1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wolf-Yadlin A, Ross PL, Pappin DJ, Rush J, Lauffenburger DA, et al. Time-resolved mass spectrometry of tyrosine phosphorylation sites in the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling network reveals dynamic modules. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1240–50. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500089-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey A, Podtelejnikov AV, Blagoev B, Bustelo XR, Mann M, Lodish HF. Analysis of receptor signaling pathways by mass spectrometry: identification of vav-2 as a substrate of the epidermal and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:179–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf-Yadlin A, Hautaniemi S, Lauffenburger DA, White FM. Multiple reaction monitoring for robust quantitative proteomic analysis of cellular signaling networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5860–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608638104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, Guo A, Goss VL, Spek EJ, et al. Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nbt1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Condina MR, Klingler-Hoffmann M, Hoffmann P. Tyrosine phosphorylation enrichment and subsequent analysis by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS and LC-ESI-IT-MS/MS. In: Coligan John E, et al., editors. Current protocols in protein science. Unit13 1. Chapter 13. 2010. editorial board. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, et al. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010;143:1174–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoumaro-Djayoon AD, Heck AJ, Munoz J. Targeted analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation by immuno-affinity enrichment of tyrosine phosphorylated peptides prior to mass spectrometric analysis. Methods. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1285–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhai B, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Mintseris J, Gygi SP. Phosphoproteome analysis of Drosophila melanogaster embryos. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1675–82. doi: 10.1021/pr700696a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang HD, Lee TY, Tzeng SW, Horng JT. KinasePhos: a web tool for identifying protein kinase-specific phosphorylation sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W226–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong YH, Lee TY, Liang HK, Huang CM, Wang TY, Yang YH, et al. KinasePhos 2.0: a web server for identifying protein kinase-specific phosphorylation sites based on sequences and coupling patterns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W588–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hojlund K, Yi Z, Hwang H, Bowen B, Lefort N, Flynn CR, et al. Characterization of the human skeletal muscle proteome by one-dimensional gel electrophoresis and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2008;7:257–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700304-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiss N, Kanety H, Schlessinger J. Five enzymes of the glycolytic pathway serve as substrates for purified epidermal-growth-factor-receptor kinase. Biochem J. 1986;239:691–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2390691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature. 2008;452:181–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sale EM, White MF, Kahn CR. Phosphorylation of glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes by the insulin receptor kinase. J Cell Biochem. 1987;33:15–26. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240330103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper JA, Esch FS, Taylor SS, Hunter T. Phosphorylation sites in enolase and lactate dehydrogenase utilized by tyrosine protein kinases in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7835–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo W, Slebos RJ, Hill S, Li M, Brabek J, Amanchy R, et al. Global impact of oncogenic Src on a phosphotyrosine proteome. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3447–60. doi: 10.1021/pr800187n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Altered glycolytic and oxidative capacities of skeletal muscle contribute to insulin resistance in NIDDM. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:166–71. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ptitsyn A, Hulver M, Cefalu W, York D, Smith SR. Unsupervised clustering of gene expression data points at hypoxia as possible trigger for metabolic syndrome. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:318. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaid H, Talior-Volodarsky I, Antonescu C, Liu Z, Klip A. GAPDH binds GLUT4 reciprocally to hexokinase-II and regulates glucose transport activity. Biochem J. 2009;419:475–84. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lochhead PA, Kinstrie R, Sibbet G, Rawjee T, Morrice N, Cleghon V. A chaperone-dependent GSK3beta transitional intermediate mediates activation-loop autophosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:627–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lochhead PA, Sibbet G, Morrice N, Cleghon V. Activation-loop autophosphorylation is mediated by a novel transitional intermediate form of DYRKs. Cell. 2005;121:925–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skurat AV, Dietrich AD. Phosphorylation of Ser640 in muscle glycogen synthase by DYRK family protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2490–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hojlund K, Staehr P, Hansen BF, Green KA, Hardie DG, Richter EA, et al. Increased phosphorylation of skeletal muscle glycogen synthase at NH2-terminal sites during physiological hyperinsulinemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:1393–402. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glintborg D, Hojlund K, Andersen NR, Hansen BF, Beck-Nielsen H, Wojtaszewski JF. Impaired insulin activation and dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase in skeletal muscle of women with polycystic ovary syndrome is reversed by pioglitazone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3618–26. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahrenholz AM, Wang YH, Roach PJ. Catalytic site of rabbit glycogen synthase isozymes. Identification of an active site lysine close to the amino terminus of the subunit. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10561–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng J, Zhu M, Schaub MC, Gehrig P, Roschitzki B, Lucchinetti E, et al. Phosphoproteome analysis of isoflurane-protected heart mitochondria: phosphorylation of adenine nucleotide translocator-1 on Tyr194 regulates mitochondrial function. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:20–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumann D, Schlattner U, Wallimann T. A molecular approach to the concerted action of kinases involved in energy homoeostasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:169–74. doi: 10.1042/bst0310169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao X, Leon IR, Bak S, Mogensen M, Wrzesinski K, Hojlund K, et al. Phosphoproteome analysis of functional mitochondria isolated from resting human muscle reveals extensive phosphorylation of inner membrane protein complexes and enzymes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000299. M110 000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cesaro L, Salvi M. Mitochondrial tyrosine phosphoproteome: new insights from an up-to-date analysis. Biofactors. 36:437–50. doi: 10.1002/biof.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hojlund K, Yi Z, Lefort N, Langlais P, Bowen B, Levin K, et al. Human ATP synthase beta is phosphorylated at multiple sites and shows abnormal phosphorylation at specific sites in insulin-resistant muscle. Diabetologia. 53:541–51. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goel HL, Dey CS. Insulin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of myosin heavy chain and concomitant enhanced association of C-terminal SRC kinase during skeletal muscle differentiation. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:557–61. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harney DF, Butler RK, Edwards RJ. Tyrosine phosphorylation of myosin heavy chain during skeletal muscle differentiation: an integrated bioinformatics approach. Theor Biol Med Model. 2005;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamauchi K, Milarski KL, Saltiel AR, Pessin JE. Protein-tyrosine-phosphatase SHPTP2 is a required positive effector for insulin downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:664–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.