Abstract

Antibiotics have been useful in the treatment of H. pylori-related benign and malignant gastroduodenal diseases. However, emergence of antibiotic resistance often decreases the eradication rates of H. pylori infections. Many factors have been implicated as causes of treatment failure, but the main antibiotic resistance mechanisms described to date are due to point mutations on the bacterial chromosome, a consequence of a significantly phenotypic variation in H. pylori. The prevalence of antibiotic (e.g., clarithromycin, metronidazole, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and furazolidone) resistance varies among different countries; it appears to be partly determined by geographical factors. Since the worldwide increase in the rate of antibiotic resistance represents a problem of relevance, some studies have been performed in order to identify highly active and well-tolerated anti-H. pylori therapies including sequential, concomitant quadruple, hybrid, and quadruple therapy. These represent a promising alternatives in the effort to overcome the problem of resistance. The aim of this paper is to review the current status of antibiotic resistance in H. pylori eradication, highlighting the evolutionary processes in detail at alternative approaches to treatment in the past decade. The underlying resistance mechanisms will be also followed.

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped, microaerophilic Gram-negative flagellate bacterium that may contribute to diseases such as duodenal/gastric ulcer disease, gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated tissue lymphoma (MALT) and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Given this relationship with human diseases, eradication of H. pylori in individuals may be the best course of action. In fact patients who receive H. pylori eradication therapy (proton pump inhibitor (PPI), amoxicillin (AMO), and clarithromycin (CLA)) often encounter eradication failure over their treatment period. Moreover, the effectiveness of “legacy triple therapy” which was recommended by Maastricht III Consensus Report provides disappointingly low treatment success (i.e., below 80%) in the world. And what could account for the resulting low treatment success or eradication failure? The reasons for this fall in effectiveness are uncertain but may be mainly related to the development of antibiotic resistant strains of H. pylori. In this paper, we will review the latest findings on H. pylori and antibiotic resistance and then summarize the factors for H. pylori eradication failure according to the current treatment regimens.

2. Nature of H. Pylori and Intragastric Environment

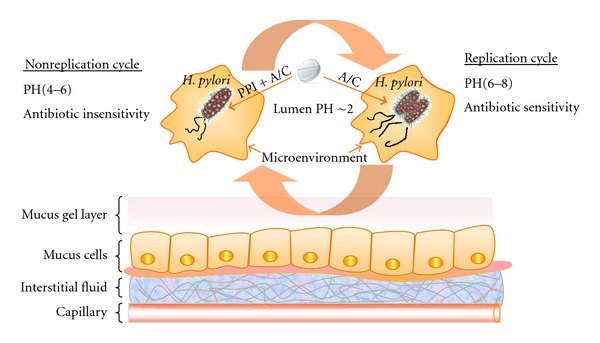

The stomach environment where the H. pylori resides was thought to be a virtual desert for microbes because of its high acidity. We now know H. pylori dominates the microbiome in the stomach, although the effect of this dominance is unclear [1]. A major opportunity to increase our understanding of this microbiome is massive parallel pyrosequencing of bacteria 16S amplicons. This will allow us to deeply characterize the microbiota of a wide range of subjects [2]. One such study used this small subunit 16S rDNA clone library to analyze 1833 sequences generated by broad-range bacterial PCR from 23 gastric endoscopic biopsy samples. This data suggests that H. pylori was the only member of the genus Helicobacter found in these human stomach samples and was the most abundant phylotype within the libraries which tested positive for this organism by using conventional clinical approaches [3]. The huge population of H. pylori is also the statistical basis of existing population of resistant organisms [4]. In addition, the bacteria oscillates between a replicating state (organism remains susceptible to the antibiotic) and nonreplicating state (the organism become phenotypically resistant) according to the pH in the microenvironments. Thus, they may enter to a nonreplicative but viable state when the pH around their microenvironments is between 4.0 and 6.0. These organisms will be difficult to eradicate, in other words, if they present the phenotypically resistant state [5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

H. pylori oscillates between a replicating state (antibiotic sensitivity) and nonreplicating state (antibiotic insensitivity) according to the pH in the microenvironments, and PPI synergizes with the antibiotics by effectively increasing gastric pH and disrupts the acidic environment preferred by HP. PPI: proton pump inhibitor, A: amoxicillin, C: clarithromycin.

H. pylori infection also presents a unique therapeutic challenge. Determining the optimal drug therapy of such infection depends to a large extent on antimicrobial concentrations in the stomach, while it is difficult because the organism lives in an environment that is not easily accessible to some medications [6]. Upon entry into the stomach, the first hurdle for bioavailability of antibiotics is the acidity of the gastric lumen, which in humans has a median 24 h intragastric pH of 1.4 [7]. A good example of this is one of the most acid-labile antibiotics against H. pylori, such as clarithromycin (CLA), which is degraded in the lumen mainly through the action of acid and pepsin. Its half life is less than 1 h in this circumstance. It became clear early on that antibiotic treatment alone was relatively ineffective. Thus, increasing intragastric pH by the coadministration of potent gastric acidity inhibitors has been shown to significantly avoid eradication failure [8]. The second hurdle is the particular structure of gastric mucus. To successfully kill the bacteria present in the stomach it is necessary that the drug is delivered to the entire surface of the stomach and penetrates across the mucus layer from gastric lumen to epithelial surface (or vice versa); furthermore, the antibiotic must reach higher concentrations for a sufficient time to efficiently kill the bacteria wherever they are present [9]. Otherwise, the bacteria in such sites can recolonize the gastric epithelium, resulting in eradication failure [10]. Significant work should be undertaken in an attempt to overcome the gastric barrier, including developing several strategies to target either the transcellular or the paracellular pathway for drug delivery.

3. Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance

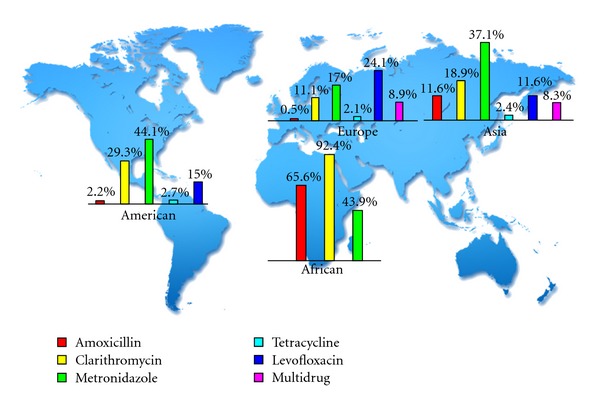

It is now believed that some populations with high incidences of H. pylori infection, such as those in East Asian countries, have high incidences of gastric cancer, while other highly infected populations do not. This apparent anomaly has been termed the “African enigma” or “Asian enigmas”. It might be explained by diverse the H. pylori genotypes, especially cagA and vacA, circulating in different geographic areas [11, 12]. Like the H. pylori infection associated with geographic areas, the prevalence of resistance rates appears to be partly determined by geographical factors; the prevalence of CLA and metronidazole (MET) resistance in China both increased from 12.8 to 23.8% and, 12.8 to 56.6%, respectively, while AMO resistance decreased from 2.1% to 0.3%, between 2000 to 2009 [13]. In Japan, adverse resistance rates to CLA increased from 7% to 15.2%, and the rate has remained fairly constant to the present day [14]. A high resistance of MET has been reported from Saudi Arabia. The rate of resistance to MET in 2008 was 69.5%, while CLA and AMO resistance rates were 21% and 0%, respectively [15]. In Europe, there are huge differences between southern and northern Europe. Higher resistance rates of clarithromycin in adults are observed in southern European countries such as Spain where the rate of CLA resistance was 35.6% in patient isolates of H. pylori [16]. Generally speaking, it was as high up as 20% compared to northern European countries [17, 18]. CLA resistance is seemingly common in the USA, ranging 10–15%, while MET resistance rates are 20–40% and resistance to amoxicillin appears to be infrequent [19, 20]. Mendonça et al. analyzed 90 Brazilian dyspeptic patients and revealed that resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin, metronidazole, tetracycline (TET), amoxicillin (AMO), and furazolidone (FUR) was 7%, 42%, 7%, 29%, and 4%, respectively [21]. A meta-analyses reported the overall H. pylori antibiotic resistance rates worldwide (31 studies from 1993 to 2009) which showed an overall H. pylori antibiotic resistance rate for AMO, CLA, MET, TET, levofloxacin (LEV), and multidrug-based therapies in different continental areas [22]. Detailed resistance rates towards antibiotics in different continental areas are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Antibiotic resistance rates in different continental areas.

Some of the reasons for these findings may include the following (1) CLA was widely administered as monotherapy for respiratory infections and as a consequence high resistance rates are reported in these countries [23]. (2) The prevalence of antibiotic resistance in various regions is correlated with the general use of antibiotics in the region, while countries with a prudent consumption of macrolides continues to be low [24]. (3) H. pylori strains have been divided into five major groups (east Asian type, south/central Asian type, Iberian/African type, and European type) according to geographical associations [25]. Thus, geographic differences associated with the presence of phylogeographic features of H. pylori may be a factor to explain the existing different antibiotic resistances [26, 27].

4. Current Anti-H. Pylori Regimens

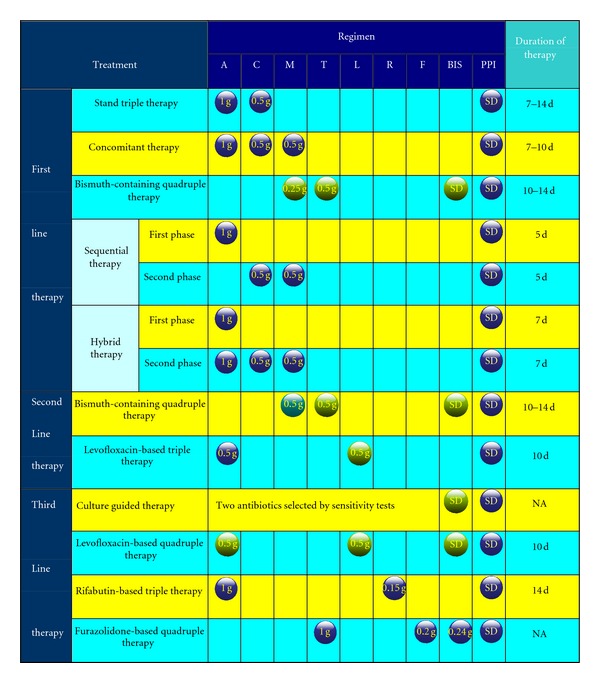

H. pylori eradication therapy, including antibiotics, PPI, and/or bismuth given for one or two weeks, has emerged as the treatment of choice (Figure 3). Standard triple therapy which represents the accepted standard therapy for H. pylori is known to be susceptible to clarithromycin, and local antimicrobial resistance rates are below to 20% [28], while newer treatment regimens (sequential, quadruple, concomitant, and hybrid therapies) and various combinations of new and old antibiotics aimed at eradicating the organism more effectively are increasing in popularity [29, 30].

Figure 3.

Current recommended regimens for H. pylori eradication. The figure in the ball stands for dose. Blue ball: b.i.d, purple ball: t.i.d, green ball: q.i.d. A: amoxicillin, C: clarithromycin, M: metronidazole, T: tetracycline, L: levofloxacin, R: rifabutin, F: furazolidone, SD: standard dose, BIS: bismuth, PPI: proton pump inhibitor, modified from [31–41].

First Line Therapy —

As first-line therapy in areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori strains, a novel 10 d sequential therapy should be considered. The sequential regimen containing a dual therapy (PPI and amoxicillin for 5 days) was followed by triple therapy with a PPI, clarithromycin, and tinidazole (or metronidazole) for 5 days. The eradication rate achieved with the sequential regimen has been reported significantly greater than that obtained with the standard treatment [32, 42]. However, it has shown that sequential therapy is ineffective in clearing H. pylori in patients with dual resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole [23, 33]. Another new regimen term as concomitant therapy is a 4-drug non-bismuth-containing regimen (PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole), which appears more suitable for patients in high endemic areas of dual resistance. Clinically, it is also more simple than sequential therapy as the drugs are all given together instead of changing drugs in halfway and might improve compliance. In addition, an intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated sequential or concomitant therapy with a PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and an imidazole agent has similar rates for eradication of H. pylori infection [42]. With regard to dual resistance, several attempts, such as the extension of sequential therapy duration and continuing the amoxicillin for the full 14 days of therapy, have been undertaken to improve the efficacy of the standard PPI triple therapy. Recently, a sequential-concomitant hybrid therapy (dual-concomitant) was designed by Hsu et al. [43]. The date showed that it provides a promising success rate of 99% by per-protocol analysis and 97% by intention-to-treat analysis. However, it must be noted that it may not work in all geographic areas, and the results will need to be confirmed in areas where different patterns of resistant are present.

Second Line Therapy —

Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as second-line and/or salvage therapy was recommended by Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report [34]. Several multicenter studies of quadruple therapy using a single-triple (bismuth biskalcitrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline) capsule preparation with PPI have shown good efficacy for eradication of H. pylori [35, 36, 44]. Convenience packs that contain most of drugs in a plasticized sheet also reduce the number of pills to improve adherence. As for adverse effects, toxic effects related to bismuth are still one of the unjustified safety concerns against the quadruple therapy [37], thus, we needed to establish the reasonable bismuth dosing regimen that provides maximum eradication.

In patients who failed with clarithromycin-based triple in first line, levofloxacin-based triple therapy (levofloxacin, amoxicillin, and a PPI) has been proven in a meta-analysis which showed that this regimen was superior to quadruple therapy and fewer side effects as salvage therapy [45]. Additionally, the study revealed that antibiotics (i.e., levofloxacin) within this triple regimens cannot randomly be changed and then switched to first line. For antibiotic resistance, rising rates of levofloxacin resistance especially in developing countries remain to be taken into account, and it appears more likely that quinolone resistance is usually relating to patients who have routinely received a fluoroquinolone for other indications [38].

Third-Line Therapy —

To date, the standard third-line therapy for refractory H. pylori infection has not been established. Maastricht IV reports recommend that anti-H. pylori treatment should be guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing after failure of second-line therapy, whenever possible [34]. Unfortunately, antimicrobial sensitivity data for patients who failed eradication therapy is still not widely available in clinical practice. For practitioners, several simple empirical management strateges are necessary.

A recent prospective study assesses the efficacy and safety of levofloxacin, amoxicillin, bismuth, and rabeprazole quadruple therapy as third-line treatment for patients who failed to eradicate H. pylori infection. In this investigation, the 10-day levofloxacin and amoxicillin-based quadruple rescue therapy provides superior eradication with an additional clinically important benefit of improved tolerability due to fewer side effects [30]. Other alternative candidates for third-line therapy are rifabutin; quinolones therapy is also promising [39, 40, 46], though the optimal dose and combination need further study.

5. Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in the Current Regimens

As a general rule for the treatment, it is defined on meeting or exceeding predefined per-protocol threshold cure rates (e.g., >90%), that is, eradication failure less than 10% [47]. H. pylori's antimicrobial resistance rates vary as mentioned above. H. pylori eradication failures may be due to acquiring chromosomal mutations or by acquisition of foreign genes carried on mobile genetic elements (horizontal gene transfer) that cause changes in each drug's site of action [23, 48], and it cannot be reversed by increasing the dose or duration [41]. Each of these mechanisms will be elucidated in more detail below according to the current anti-H. pylori regimens.

Clarithromycin —

In a recent study involving sequencing analysis of H. pylori gene 23S rRNA isolated from Uruguayan patients, all CLA-resistant strains point mutation were presented in position 2143 (A-to-G transition), consistent with strains studied in some developing countries worldwide. No AMO-resistant strains were identified in this study, this is most frequently reported with AMO where failure is rarely caused by acquired resistance [49, 50]. Other mutations at position 2142 (A-to-G transition) and position 2182 (C-to-T transition) have been confirmed by analysis of DNA sequencing to be the same as that described at position 2143 and are associated with CLA resistance [51]. Except for 23S rRNA mutations, expression of a resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) type efflux pump, an active drug efflux mechanism responsible for rapidly transferring the drug out of the bacterial cell, preventing the binding of the antibiotic to the ribosome, plays an important role in acquiring CLA resistance [52, 53]. Nevertheless, it was shown that efflux systems are not involved in the intrinsic resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics or in acquired resistance to AMO [54].

Amoxicillin —

Rare tolerance to AMO has also been described and was associated to alterations in penicillin binding proteins (PBP1A) [55]. Three substitutions (Ser 414 Arg, Thr 556Ser, and Asn 562) are the most common amino acid changes in PBP1 connected to AMO resistance. Consequently, this reduces the susceptibility of these strains to the bactericidal effect of AMO [56].

Metronidazole —

Metronidazole (MET) resistance in H. pylori is complex and is primarily associated with mutational inactivation of the redox-related gene (frxA, rdxA) [57]. FrxA may act indirectly by affecting cellular reductive potential in low level MET resistant isolates. RdxA gene inactivation confers resistance by saturation transpose on mutagenesis of the H. pylori genome [58, 59]. Thus, factors that lead to the loss of or inactivation of the two genes may lead to contribute to MET resistance per se. Meanwhile, there are reports that the MET resistance phenotype may arise in H. pylori without mutations in rdxA or frxA, suggesting the presence of additional MET resistance mechanisms [60]. Choi et al. proposed that several mutational changes in H. pylori Fur proteins can affect MET susceptibility via altering the balance among Fur's several competing activities and thereby eliminating bactericidal MET activation products [61].

Fluoroquinolone —

The mechanism of fluoroquinolone (FLU) resistance in H. pylori has been found to be linked to mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of the gyrase A (gyrA) gene [62]. This region, responsible for DNA cleavage and rearrangement, is also the position of action of quinolones [39]. A recent study performed in Korea has shown this resistance was considered to depend mainly on gyrA gene mutation at Asn87 or Asp91 [63], and mutation in the gyrB gene has also been identified in LEV resistant strains. This rarely occurs and often occurs together with gyrA mutations. This indicates that gyrB has little impact on primary levofloxacin resistance. In addition, gyrA gene has double gyrA mutations hot spots at N87K and D91G or D91Y which were linked to high-level fluoroquinolone resistance by laboratory mutants [64].

Rifabutin —

Rifabutin (RIF) is a spiropiperidyl rifamycin-S derivative, which inhibits the B-subunit of the DNA-directed RNA polymerase (rpoB) of H. pylori. RIF has potential activity against H. pylori because the in vitro sensitivity is high, and it does not share resistance to either CLA or AMO [65, 66]. It is structurally related to rifampin (rifampicin) and shares many of its properties. The mechanism of H. pylori resistance to this group of antibiotics is not known, only some studies clearly show that it is substantial cross-resistance in vitro between rifabutin and rifampin, mainly caused by point mutations occurring in the rpoB gene at codons 524, 525, and 585 as in other bacteria [66–68].

Tetracycline —

Tetracycline (TET) is an antibiotic that is commonly used to eradicate H. pylori infection in several second-line regimens. The bactericidal activity of TET is a result of the drug's ability to prevent the synthesis of nascent peptide chains via binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit as well as blocking the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA [69]. The best-studied resistant mechanism has been mostly associated with de novo mutations in the 16S rRNA gene, which is based on a single, double or triple base-pair substitution in adjacent 16S rRNA gene [70]. In the case of mutation that cause resistance, single or double base-pair substitutions (A928C, AG926-927→GT and A926G/A928C) as well as triple substitution (AGA926–928→TTC) confer H. pylori with low and high-level TET resistance [71]. The phenotype observed in the case of this mutant is similar to those observed by Gerrits et al. [72]. Probably, decreased antibiotic binding of the drug for the ribosome reduces its antibiotic property. Resistance to TET is also related to a proton motive force (PMF)-dependent efflux of TET across the cell membrane. Consistent with efflux studies, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), an inhibitor that disrupts the proton gradient across the membrane, leads to antibiotic accumulation by presence or absence of it. Therefore, it plays an important role in the resistance of clinical isolates of H. pylori to TET [73].

6. Conclusion

H. pylori is considered pathogenic, even carcinogenic. With this simple view, eradication is considered as an obvious choice. In reality, however, the rate of eradication failure has dramatically risen in many countries due to resistance to antibiotics. On genetic support, mutation is considered as the key phenotypic variation as well as response to selection stress. Other suspected mechanisms of acquired drug resistance include: decreased permeation of the antibiotic into the bacterial cell and multidrug efflux pumps confer resistance to β-lactams [54]. An opportunity to solve this is whole-genome sequencing of multiple isolates of individual patients with dense spatial and temporal sampling. A practical application is the detection of genomic changes related to drug resistance by comparing the genomes of wild-type strains and those that survived antibiotic treatments [74, 75]. Furthermore, in the context of clinic treatment, selection pressure exerted by the long-term use of antibiotics, drug adverse effect, patient tolerability, adherence, even the patient's disease status should considered by doctors [4]. It is important to remember that antibiotic resistance can often be partially overcome by susceptibility and DNA testing and differentiation of recrudescence and reinfection. Highly active and well-tolerated regimen should be sought and appropriately tested in randomized controlled trial (RCT) instead of simply following consensus guidelines.

Conflict of Interests

There is no conflict of interest to disclose for all authors.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully thank Dr. Minal Patel (Department of Communicative Disorders and Sciences, Center for Hearing and Deafness, Buffalo, NY 14214, USA) for revising the paper.

References

- 1.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer byHelicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich MJ. Microbiome project seeks to understand human body’s microscopic residents. JAMA. 2008;300(7):777–778. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, et al. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(3):732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59(8):1143–1153. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott D, Weeks D, Melchers K, Sachs G. The life and death of Helicobacter pylori . Gut. 1998;43(supplement 1):S56–S60. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2008.s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vakil N, Megraud F. Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):985–1001. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom SR, Polak JM. Physiology of gastrointestinal hormones. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1980;8(1):15–17. doi: 10.1042/bst0080015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moayyedi P, Sahay P, Tompkins DS, Axon ATR. Efficacy and optimum dose of omeprazole in a new 1-week triple therapy regimen to eradicate Helicobacter pylori . European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1995;7(9):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Midolo PD, Turnidge JD, Munkhof WJ, Berry V, Woodnutt G. Is bactericidal activity of amoxicillin against Helicobacter pylori concentration dependent? Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1996;40(5):1327–1328. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atherton JC, Cockayne A, Balsitis M, Kirk GE, Hawkey CJ, Spiller RC. Detection of the intragastric sites at which Helicobacter pylori evades treatment with amoxycillin and cimetidine. Gut. 1995;36(5):670–674. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.5.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalebi A, Rana F, Mwanda W, Lule G, Hale M. Histopathological profile of gastritis in adult patients seen at a referral hospital in Kenya. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;13(30):4117–4121. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. African, Asian or Indian enigma, the East Asian Helicobacter pylori: facts or medical myths. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2009;10(2):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao W, Cheng H, Hu F, et al. The evolution of Helicobacter pylori antibiotics resistance over 10 years in Beijing, China. Helicobacter. 2010;15(5):460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horiki N, Omata F, Uemura M, et al. Annual change of primary resistance to clarithromycin among Helicobacter pylori isolates from 1996 through 2008 in Japan. Helicobacter. 2009;14(5):86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marie MAM. Patterns of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithormycin and amoxicillin in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Bacteriology and Virology. 2008;38(4):173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agudo S, Pérez-Pérez G, Alarcón T, López-Brea M. High prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori strains and risk factors associated with resistance in Madrid, Spain. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(10):3703–3707. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00144-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen MJR, Hendrikse L, de Boer SY, et al. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in a Dutch region: trends over time. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 2006;64(6):191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storskrubb T, Aro P, Ronkainen J, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori strains in a random adult Swedish population. Helicobacter. 2006;11(4):224–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischbach LA, Goodman KJ, Feldman M, Aragaki C. Sources of variation of Helicobacter pylori treatment success in adults worldwide: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(1):128–139. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osato MS, Reddy R, Reddy SG, Penland RL, Malaty HM, Graham DY. Pattern of primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(9):1217–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendonça S, Ecclissato C, Sartori MS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and furazolidone in Brazil. Helicobacter. 2000;5(2):79–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, et al. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2010;19(4):409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mégraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut. 2004;53(9):1374–1384. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez Aldana L, Kato M, Nakagawa S, et al. The relationship between consumption of antimicrobial agents and the prevalence of primary Helicobacter pylori resistance. Helicobacter. 2002;7(5):306–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2002.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaoka Y, Orito E, Mizokami M, et al. Helicobacter pylori in North and South America before Columbus. FEBS Letters. 2002;517(1–3):180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;7(11):629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaoka Y, Kato M, Asaka M. Geographic differences in gastric cancer incidence can be explained by differences between Helicobacter pylori strains. Internal Medicine. 2008;47(12):1077–1083. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56(6):772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu PP, Rayapudi K, Pacana T, Shah NJ, Krishnaswamy N, Flynn M. A randomized study comparing levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline versus triple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori . The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106(11):1970–1975. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu PI, Wu DC, Chen A, et al. Quadruple rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection after two treatment failures. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;38(6):404–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuah S-K, Tsay F-W, Hsu P-I, Wu D-C. A new look at anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(35):3971–3975. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, O’Connor A, Mégraud F, O’Morain CA. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a critical review. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;44(5):313–325. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c8a1a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori infection. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;8(1):36–41.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/ Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Morain C, Borody T, Farley A, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-triple capsules of bismuth biskalcitrate, metronidazole and tetracycline, given with omeprazole, for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: an international multicentre study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2003;17(3):415–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laine L, Hunt R, EI-Zimaity H, Nguyen B, Osato M, Spénard J. Bismuth-based quadruple therapy using a single capsule of bismuth biskalcitrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in duodenal ulcer patients: a prospective, randomized, multicenter, North American trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98(3):562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.t01-1-07288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips RH, Whitehead MW, Doig LA, et al. Is eradication of Helicobacter pylori with colloidal Bismuth subcitrate quadruple therapy safe? Helicobacter. 2001;6(2):151–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chey WD, Wong BCY. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102(8):1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Hibi T. Quinolone-based third-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2009;44(2):119–124. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-220R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Der Poorten D, Katelaris PH. The effectiveness of rifabutin triple therapy for patients with difficult-to-eradicate Helicobacter pylori in clinical practice. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2007;26(11-12):1537–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mégraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2007;20(2):280–322. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146(8):556–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu PI, Wu DC, Wu JY, Graham DY. Modified Sequential Helicobacter pylori therapy: proton pump inhibitor and amoxicillin for 14 days with clarithromycin and metronidazole added as a quadruple (hybrid) therapy for the final 7 days. Helicobacter. 2011;16(2):139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2011;377(9769):905–913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liou JM, Lin JT, Chang CY, et al. Levofloxacin-based and clarithromycin-based triple therapies as first-line and second-line treatments for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomised comparative trial with crossover design. Gut. 2010;59(5):572–578. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.198309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toracchio S, Capodicasa S, Soraja DB, Cellini L, Marzio L. Rifabutin based triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori primary and secondary resistant to tinidazole and clarithromycin. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2005;37(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimbara E, Fischbach LA, Graham DY. Optimal therapy for Helicobacter pylori infections. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;8(2):79–88. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falush D, Kraft C, Taylor NS, et al. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(26):15056–15061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251396098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torres-Debat ME, Pérez-Pérez G, Olivares A, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori and mechanisms of clarithromycin resistance in strains isolated from patients in Uruguay. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2009;101(11):757–762. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082009001100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vilaichone RK, Mahachai V, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori Diagnosis and Management. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2006;35(2):229–247. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen S, Li Y, Yu C. Oligonucleotide microarray: a new rapid method for screening the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori for single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with clarithromycin resistance. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;23(1):126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirata K, Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, et al. Contribution of efflux pumps to clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori . Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;25(supplement 1):S75–S79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webber MA, Piddock LJV. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2003;51(1):9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeLoney CR, Schiller NL. Characterization of an in vitro-selected amoxicillin-resistant strain of Helicobacter pylori . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2000;44(12):3368–3373. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3368-3373.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerrits MM, Godoy APO, Kuipers EJ, et al. Multiple mutations in or adjacent to the conserved penicillin-binding protein motifs of the penicillin-binding protein 1A confer amoxicillin resistance to Helicobacter pylori . Helicobacter. 2006;11(3):181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qureshi NN, Morikis D, Schiller NL. Contribution of specific amino acid changes in penicillin binding protein 1 to amoxicillin resistance in clinical Helicobacter pylori isolates. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2011;55(1):101–109. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00545-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsugawa H, Suzuki H, Satoh K, et al. Two amino acids mutation of ferric uptake regulator determines Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2011;14(1):15–23. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore JM, Salama NR. Mutational analysis of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2005;49(3):1236–1237. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1236-1237.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matteo MJ, Pérez CV, Domingo MR, Olmos M, Sanchez C, Catalano M. DNA sequence analysis of rdxA and frxA from paired metronidazole-sensitive and -resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates obtained from patients with heteroresistance. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2006;27(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bereswill S, Krainick C, Stähler F, Herrmann L, Kist M. Analysis of the rdxA gene in high-level metronidazole-resistant clinical isolates confirms a limited use of rdxA mutations as a marker for prediction of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori . FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2003;36(3):193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi SS, Chivers PT, Berg DE. Point mutations in Helicobacter pylori’s fur regulatory gene that alter resistance to metronidazole, a prodrug activated by chemical reduction. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018236.e18236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tankovic J, Lascols C, Sculo Q, Petit JC, Soussy CJ. Single and double mutations in gyra but not in gyrb are associated with low- and high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Helicobacter pylori . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2003;47(12):3942–3944. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3942-3944.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chung J-W, Lee GH, Jeong J-Y, et al. Resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains to antibiotics in Korea with a focus on fluoroquinolone resistance. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27(3):493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyachi H, Miki I, Aoyama N, et al. Primary levofloxacin resistance and gyrA/B mutations among Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Helicobacter. 2006;11(4):243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akada JK, Shirai M, Fujii K, Okita K, Nakazawa T. In vitro anti-Helicobacter priori activities of new rifamycin derivatives, KRM-1648 and KRM-1657. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1999;43(5):1072–1076. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heep M, Beck D, Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N. Rifampin and rifabutin resistance mechanism in Helicobacter pylori . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1999;43(6):1497–1499. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suzuki S, Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, et al. Past rifampicin dosing determines rifabutin resistance of Helicobacter pylori . Digestion. 2009;79(1):1–4. doi: 10.1159/000191204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glocker E, Bogdan C, Kist M. Characterization of rifampicin-resistant clinical Helicobacter pylori isolates from Germany. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2007;59(5):874–879. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2001;65(2):232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribeiro ML, Gerrits MM, Benvengo YHB, et al. Detection of high-level tetracycline resistance in clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori using PCR-RFLP. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2004;40(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toledo H, López-Solís R. Tetracycline resistance in Chilean clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori . Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009;65(3):470–473. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gerrits MM, De Zoete MR, Arents NLA, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. 16S rRNA mutation-mediated tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2002;46(9):2996–3000. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2996-3000.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anoushiravani M, Falsafi T, Niknam V. Proton motive force-dependent efflux of tetracycline in clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori . Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58(10):1309–1313. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.010876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dorer MS, Talarico S, Salama NR. Helicobacter pylori’s unconventional role in health and disease. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000544.e1000544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suzuki R, Shiota S, Yamaoka Y. Molecular epidemiology, population genetics, and pathogenic role of Helicobacter pylori . Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]