Abstract

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc-DBS) was associated with antidepressant, anxiolytic, and procognitive effects in a small sample of patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression (TRD), followed over 1 year. Results of long-term follow-up of up to 4 years of NAcc-DBS are described in a group of 11 patients. Clinical effects, quality of life (QoL), cognition, and safety are reported. Eleven patients were stimulated with DBS bilateral to the NAcc. Main outcome measures were clinical effect (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Montgomery-Asperg Rating Scale of Depression, and Hamilton Anxiety Scale) QoL (SF-36), cognition and safety at baseline, 12 months (n=11), 24 months (n=10), and last follow-up (maximum 4 years, n=5). Analyses were performed in an intent-to-treat method with last observation carried forward, thus 11 patients contributed to each point in time. In all, 5 of 11 patients (45%) were classified as responders after 12 months and remained sustained responders without worsening of symptoms until last follow-up after 4 years. Both ratings of depression and anxiety were significantly reduced in the sample as a whole from first month of NAcc-DBS on. All patients improved in QoL measures. One non-responder committed suicide. No severe adverse events related to parameter change were reported. First-time, preliminary long-term data on NAcc-DBS have demonstrated a stable antidepressant and anxiolytic effect and an amelioration of QoL in this small sample of patients suffering from TRD. None of the responders of first year relapsed during the observational period (up to 4 years).

Keywords: DBS, nucleus accumbens, treatment-resistant major depression, anxiety, quality of life, relapse

INTRODUCTION

A large number of depressive patients cannot be helped with evidence-based treatment steps (eg, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy). Up to 40% of patients responding to antidepressant therapy suffer from clinically relevant residual symptoms despite optimized treatment (Fava and Davidson, 1996). These patients suffer from debilitating, life-threatening symptoms, face a reduced quality of life (QoL), and are a burden for society (Murray and Lopez, 1996; Pincus and Pettit, 2001). For these patients, suffering from so-called treatment-resistant depression (TRD), deep brain stimulation (DBS) is currently under research as a possible treatment option.

DBS aims to modulate dysfunctional neuronal networks involved in depression (Krishnan and Nestler, 2010). Three major brain regions have been selected in a hypothesis-driven way for major depression: nucleus accumbens (NAcc) (Bewernick et al, 2010; Schlaepfer and Lieb, 2005), subgenual cingulate cortex (Cg25) (Lozano et al, 2008; Mayberg et al, 2005) and the anterior limb of the capsula interna (ALIC) (Malone et al, 2009). Although the precise mechanism of action is not known yet, significant antidepressant effects have been shown in a 1-year follow-up period in 50–60% of the about 45 treated patients (Bewernick et al, 2010; Lozano et al, 2008; Malone et al, 2009). A normalization of brain metabolism in the target region and in brain areas belonging to neuronal network modulated by DBS has been demonstrated (Bewernick et al, 2010; Lozano et al, 2008). Neuropsychological assessment showed a normalization of previously sub-average performance in several cognitive domains in a 1-year follow-up (Grubert et al, 2011; McNeely et al, 2008).

Despite encouraging antidepressant effects of all targets, long-term outcome beyond 1 year has only been described recently in 14 patients stimulated at Cg25 with 45% response after 2 years, 60% response after 3 years, and 55% response at last follow-up visit (up to 6 years) (Kennedy et al, 2011) and in a sample of 17 patients targeting the ALIC (Malone, 2010). Response rates were 53% after 12 months and 71% at last follow-up (ranging from 14 to 67 months) (Malone, 2010). The response criterion was a minimum of 50% reduction in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) or Montgomery-Asperg Rating Scale of Depression (MADRS) in all studies.

In this study, long-term effects of DBS to the NAcc are described in a group of 11 patients suffering from TRD. Clinical effects, QoL, cognition, and safety over a 2-year follow-up period, in five patients up to 4 years, are reported.

Contrary to the high relapse rates after treatment-as-usual (TAU) (eg, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) (Rush et al, 2006), but in line with stable antidepressant, anti-anhedonic, and anxiolytic effects of NAcc-DBS during first year, we hypothesized, that clinical effects as well as an increase in QoL would be stable during long-term follow-up (from 12 to 48 months).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The study has been approved by the institutional review boards of the Universities of Bonn and Cologne. Eleven patients between 32 and 65 years of age received NAcc-DBS (see Table 1 for demographic data) Selection criteria were a minimum score on the 28-item HDRS (HDRS28) of 21, a score in Global Assessment of Function below 45. Further inclusion criteria were at least four episodes of major depressive disorder (MDD) or chronic episode over 2 years; >5 years after first episode of MDD; failure to respond to adequate trials of primary antidepressants from at least three different classes, adequate trials of augmentation/combination of a primary antidepressant using at least two different augmenting/combination agents; an adequate trial of ECT (>6 bilateral treatments); an adequate trial of individual psychotherapy (>20 sessions); and no psychiatric co-morbidity and drug free or on stable drug regimen at least 6 weeks before study entry. Exclusion criteria were current or past nonaffective psychotic disorder; any current clinically significant neurological disorder or medical illness affecting brain function, or severe personality disorder. Patients met diagnostic criteria for MDD, unipolar type, and were in a current episode. All patients to be included in the study suffered from severely TRD (Sackeim, 2001).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Variable | Mean | SD |

Responders

|

Non-responders

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age at implant (years) | 48.36 | 11.08 | 45.6 | 12.9 | 50.6 | 9.8 |

| Sex (% female) | 33 | 60 | 16.6 | |||

| Duration of education (years) | 14.30 | 2.36 | 14.25 | 2.5 | 14.3 | 2.5 |

| Retirement because of depression (% retired) | 90.00 | 80 | 100 | |||

| Length of current episode (years) | 9.26 | 7.64 | 5.98 | 3.5 | 12 | 9.3 |

| Number of previous episodes (lifetime)a | 1.29 | 1.75 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| Age at onset (years) | 32.55 | 12.41 | 34.8 | 14.4 | 30.6 | 11.4 |

| Time since diagnosis of affective disorder (years) | 17.45 | 9.91 | 12.6 | 4.7 | 21.5 | 11.6 |

| Lengths of previous hospitalizations (months) | 20.18 | 11.24 | 18.4 | 10.2 | 21.6 | 12.7 |

| Number of antidepressive pharmaceuticals at implant | 4.36 | 1.21 | 3.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 1.1 |

| Number of past medical treatment courses | 22.18 | 7.73 | 19 | 5.5 | 24.8 | 8.7 |

| Number of medications included in formula | 13.82 | 5.34 | 12 | 4 | 15.3 | 6.1 |

| Mean total of ATHF scoreb | 40.27 | 15.24 | 38.6 | 14.3 | 41.6 | 17.1 |

| Mean ATHF score and SD | 3.18 | 0.40 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 3 | 0 |

| Average number of treatment trials with ATHF ⩾3 | 7.91 | 3.36 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 8.1 | 3.6 |

| Past ECT/MST | 21.09 | 8.48 | 22.2 | 8.7 | 20.1 | 8.9 |

| Psychotherapy (h) | 263.64 | 263.88 | 185.2 | 143.8 | 329 | 333.8 |

| Suicide attempts (% of patients preoperative) | 27 | 20 | 33.3 | |||

Fifty percent of patients did not have separate episodes.

Modified antidepressant treatment history form (ATHF). A score of ‘3' is the threshold for considering a trial adequate and the patient resistant to the treatment.

Mean and SD, if applicable, are reported.

Surgery/Target

Bilateral DBS electrodes were implanted as described previously (Schlaepfer et al, 2008) using a Leksell-stereotactic frame. Standard Medtronic model 3387 leads were used. This lead has four contacts over a length of 10.5 mm, each spaced 1.5 mm apart: (1) the shell and (2) the core regions of the NAcc, and (3) the ventral and (4) the medial internal capsule. The lowest contact was targeted at 7.5, 1.5, and 4 mm from the upper front edge of the anterior commissure, corresponding to MNI coordinates ±7.5, 5.5, and 9.0. Targets and trajectories were defined using stereotactic 3 Tesla MR imaging. Electrode positioning was verified after surgery as described in Huff et al (2010). Electrode type and location differed from the ALIC target only dorsally (Malone et al, 2009), because the electrodes used in this study had a smaller spacing of 10.5 mm and the electrodes used in the ALIC study had a wider space covering a larger brain area (Malone et al, 2009). Thus, the two most ventral ALIC contacts cover approximately the same brain area as the four contacts used in this study.

Assessment and Study Protocol

Psychiatric assessments were performed on a weekly basis during the first and second month after stimulation onset and up to half a year on a 2-weekly basis. From month 7 up to 2 years, patients were tracked on a monthly basis, then up to 4 years on a 3-monthly basis.

Primary outcome measure was antidepressant response (50% reduction of depressive symptom severity as assessed by the 28-item HDRS28 (Endicott et al, 1981; Hamilton, 1967; Rosenthal and Klerman, 1966) or remission (HDRS-score of <10)). Patients were classified as responders and non-responders with regard to their response to NAcc-DBS 12 months post-surgery. Secondary outcome measures included MADRS (Montgomery and Åsberg, 1979) and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) (Hamilton, 1976).

The Hautzinger list of positive activities is a list of 280 pleasant activities (Hautzinger, 2000; Lewinsohn and Graf, 1973). This score is used as a tool to assess progress in cognitive behavioral therapy. Lacking meaningful standardized measures of anhedonia, we used this list to assess changes in anhedonia and level of activity. Social functioning was measured with the Short-Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). The SF-36 assesses QoL in eight subscales that can be summarized into a score in ‘physical health dimension' and ‘mental health dimension'. Additionally, information about safety of the treatment method (see Table 4 for adverse events) was recorded.

Neuropsychological assessment with standardized tests was administered to the patients before implantation and once a year during follow-up. Thirteen cognitive tests were analyzed comparing baseline and last follow-up covering learning and memory (verbal and visual-spatial as well as working memory), attention, language, visual perception, and executive functions. Standard neuropsychological tests are clustered according to the Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests and described in detail elsewhere (Spreen, 1991). See Grubert et al (2011) for a detailed description of neuropsychological tests applied. Some verbal test could not be performed on all patients for language reasons (see Table 3 for number of patients included in the analysis).

Stimulation Parameters and Additional Treatments

Stimulation was applied with permanent pulse-train square wave stimulation starting with the parameters amplitude 2 V, pulse width 90 μs, frequency 130 Hz, and the electrode setting electrodes 1 and 2 negative against case. After an intra-operative trial, stimulation was switched off for 1 week to allow consolidation of the tissue surrounding the electrode tips (eg, changes in resistance) and to control for microlesional effects (Cersosimo et al, 2009; Granziera et al, 2008). One week post-operatively, this DBS setting was resumed and the voltage was successively increased from 2 to 4 V.

Stimulation parameters were kept constant approximately for 4 weeks in order to retrieve sufficient observations of first acute and sub-acute effects (eg, improvement in clinical impression as assessed by HDRS). Next, only when side effects occurred or when the antidepressant response was not satisfying, DBS parameters were varied in order to optimize the individual response. The sequence and priority of changes was: amplitude, pulse width, selection of poles, (all possible monopolar and bipolar combinations), and frequency in the range 1.5–10.0 V, 100–150 Hz, and 60–210 μs. Stimulation was always bilateral and symmetric. The individual optimum DBS setting was kept constant in each patient at least one month before and during the final follow-up.

Additional pharmacological treatment was kept constant at least 6 weeks before and after surgery. During follow-up, especially in non-responders, changes in pharmacological regime were allowed. Patients undergoing psychotherapy entering the study were allowed to continue the treatment.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate clinical response, all rating scales were analyzed with ANOVA for repeated measures and the factor time. Post-hoc paired comparisons were calculated for each time point compared with baseline. Level of significance was set at 5% for all analyses. Data from early terminators (n=1, 12 months) or patients in follow-up under 24 months (n=1, 13 months) were analyzed in the last observation carried forward manner. Missing values were interpolated. Last follow-up was up to 4 years (five patients completed year 4). All analyses were performed as intent-to-treat analysis in order to avoid overestimation of clinical effect. Significance of change in cognitive performance between baseline and last observation (up to 36 months) was analyzed via paired t-tests for each neuropsychological test as recommended by Okun et al (2007) in order to evaluate whether surgery and stimulation lead to deterioration from baseline.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

All patients were diagnosed as severely treatment resistant with a mean length of current major depressive episode of 9.2 years (SD 7.6), and had 7.9 medical treatment courses in average with an antidepressant treatment resistance score (ATHF score) above 3 defining an adequate treatment dose and length, including augmentation and combination therapy. At time of implantation, the mean number of antidepressant medications was 4.3. All patients had received ECT and psychotherapy without response (see Table 1 for demographic information). Responders and non-responders were compared concerning severity of depression at baseline (HDRS_28, MADRS) and clinical characteristics. No difference could be detected regarding baseline depressivity ((responders/non-responders HDRS_28 score: 34.5 (SD 5.2)/30.2 (SD 53); responders/non-responders MADRS score: 33.6 (SD 1.6)/31.2 (SD 4.6)) or demographic differences. Only the number of women in each group differed: three women were classified as responders (vs two men) and one woman was classified as non-responder (vs five men).

Clinical Outcomes

All measures are reported at baseline (mean baseline score over up to five visits in the last 3 months before surgery), n=11, and at several time points up to 4 years after stimulation onset (n=11).

Primary outcome (HDRS28)

Patients were classified as responders (50% reduction in HDRS) and non-responders (<50% reduction in HDRS) with regard to their response to NAcc-DBS 12 months post-surgery (Table 2, Figure 1a). Five patients (45.5%) reached the response criterion at this point; six patients (54.5%) were classified as non-responders. During the second year, response status remained stable in all patients. None of the non-responders reached response status for >2 consecutive months. One patient was in stable remission (HDRS28⩽10).

Table 2. Psychopathological Measures at Multiple Time Points During DBS Treatment.

| Baseline | 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months | 9 Months | 12 Months | 15 Months | 18 Months | 21 Months | 24 Months | Last observation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| p-Value main effect | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | |

| HDRS_28 | |||||||||||

| Group | 32.2 (5.5) | 23.2 (5.6) | 23.4 (5.1) | 20.9 (4.6) | 23.3 (5.5) | 20.2 (7.5) | 21.3 (7.1) | 21 (8.9) | 21.5 (8.1) | 19.5 (9) | 22.1(13.4) |

| F=4.1 | p<0.001 | p<0.005 | p<0.001 | p=0.001 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.05 |

| df=10 | |||||||||||

| MADRS | |||||||||||

| Group | 32.3 (3.7) | 24.2 (4.8) | 23.4 (4.7) | 20.9 (5.6) | 22.8 (6.8) | 20.2 (7.3) | 21.2 (7.8) | 21.1 (8.5) | 21.7 (9.3) | 19.1 (8.5) | 21.6 (10.7) |

| F=5.1 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.005 | p=0.001 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.05 | p<0.005 | p<0.05 |

| df=10 | |||||||||||

| HAMA | |||||||||||

| Group | 23.3 (5.7) | 17.9 (7.3) | 17.6 (5.9) | 15.4 (3.9) | 17.4 (3) | 14.3 (5.8) | 15.7 (9) | 16 (10.4) | 13.7 (6.4) | 13.9 (4.9) | 14.7 (8.8) |

| F=2.7 | p<0.005 | p<0.01 | p<0.05 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.005 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.005 | p=0.001 | p<0.05 |

| df=10 | |||||||||||

| Activities | |||||||||||

| Group | 28.5 (16) | 43.9 (24.8) | 39 (21.8) | 41.6 (24.4) | 43.2 (20.5) | 45.7 (20.7) | 45.5 (25.4) | 46.4 (25.3) | 48 (29.6) | 51.9 (35.5) | 57.9 (37.7) |

| F=2.4 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p=0.100 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p=0.052 | p<0.05 | p=0.075 | p=0.083 | p<0.05 |

| df=10 | |||||||||||

| SF 36 | |||||||||||

| Mental health | |||||||||||

| Group | 19.4 (4.9) | 23.3 (6.3) | 19.5 (3.4) | 20.5 (6.5) | 19.9 (3.8) | 24.3 (11.4) | 29.9 (11.2) | ||||

| F=4.9 | p<0.001 | p<0.05 | p=0.953 | p=0.551 | p=0.749 | p=0.172 | p<0.05 | ||||

| df=6 | |||||||||||

| Physical health | |||||||||||

| Group | 34.0 (4.5) | 35.4 (7.9) | 38.0 (5.9) | 35.7 (4.6) | 34.8 (3.9) | 37.6 (8.5) | 34.1 (13.3) | ||||

| F=0.7 | p=0.651 | p=0.42 | p=0.40 | p=0.267 | p=0.565 | p=0.182 | p=0.980 | ||||

| df=6 | |||||||||||

Abbreviations: Activities, number of positive activities after Hautzinger; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HDRS_28, Hamilton-28-Items Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; SF-36, Health Survey Questionnaire.

Mean, SD, ANOVAs for repeated measures with the factor time and post-hoc contrasts for each time point in comparison with baseline.

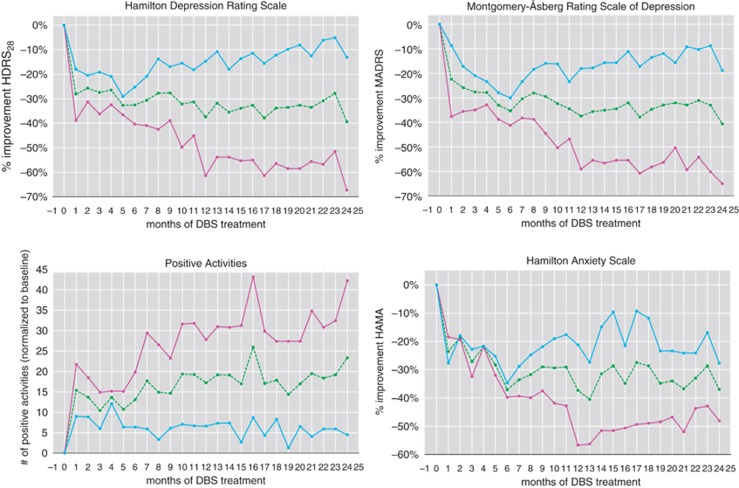

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes over time. Hamilton depression rating over time (top left); Montgomery-Asperg rating over time (top right); positive activities over time (bottom left); Hamilton anxiety rating over time (bottom right). In red responders (>50% reduction from baseline), in blue non-responders (<50% reduction from baseline), in green group mean scores. For the activities, panel red refers to patients who responded >50% in the HDRS score. At each time point, 11 patients contributed, as data were analyzed in an intent-to-treat method with last observation carried forward.

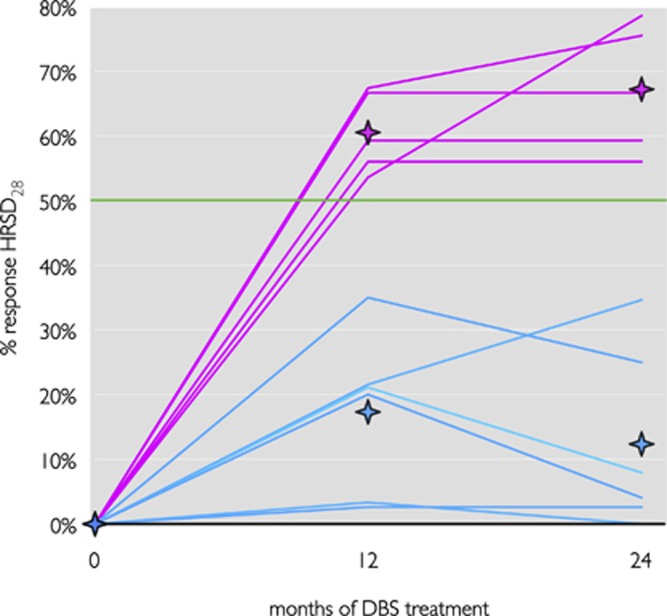

The mean total HDRS28 score was significantly improved under stimulation at all-time points. Improvements were seen after first month of stimulation in the sample as a whole (HDRS28-score: 32.2 (SD 5.5) at baseline, 23.2 (SD 5.6) after 1 month) and remained stable throughout the follow-up period (HDRS28-score: 20.2 (SD 7.5) after 1 year, 19.5 (SD 9) after 2 years, 22.1 (SD 13.4) last follow-up). Responders and non-responders descriptively differed in HDRS score after first month of stimulation and differences were more pronounced during follow-up period. In the second year, group differences were even more pronounced. Stability of anti-depressive effect in each patient is demonstrated in Figure 2. Responders at 12 months remained responders at 24 months and last follow-up, non-responders kept their status respectively.

Figure 2.

Stability of clinical effect. Individual response over time. Red lines are responders (>50% reduction from baseline), n=5, in blue non-responders (<50% reduction from baseline), n=6, at time points 12 and 24 months. Diamonds represent corresponding group mean values.

Secondary outcome variables (MADRS, HAMA, positive activities, QoL, cognition)

MADRS was used to capture changes in additional depressive symptoms (eg, cognitive functioning, level of activity, interest, and negative thinking). Group effects were similar to those measured with the HDRS28 (MADRS group mean at baseline: 32.3 (SD 3.7); group mean after 1 year: 20.2 (SD 7.3) after 2 years: 19.1 (SD 8.5) last follow-up: 21.6 (SD 10.7)) (Table 2, Figure 1b).

Improvement in depression was accompanied by a reduction in anxiety as measured by the HAMA (Table 2, Figure 1c). Compared with baseline, the sample as a whole showed a significant reduction in anxiety symptoms (HAMA at baseline: 23.3 (SD 5.7), after 1 year: 14.3 (SD 5.8), after 2 years 13.9 (SD 4.9), last follow-up: 14.7 (SD 8.8)). From first month of stimulation, the group mean was below 19, which is the cut-off for anxiety disorders in pharmacological studies (Hamilton, 1976). Similar to results in depression scales, responders had a more pronounced reduction in anxiety compared with non-responders.

The level of hedonic activities (as measured by the Hautzinger's list of positive activities) rose significantly in the sample as a whole from first month of simulation. Descriptively, the number of activities further increased in the group of responders during the follow-up period (Table 2, Figure 1d) and not in the group of non-responders. Physical health dimension (as one dimension of the QoL scale SF-36) changed from 34.0 (SD 4.5) at baseline to 34.1 (SD 11.2) at last follow-up for the group as a whole, thus patient's physical health remained stable. On a descriptive level, responders had a better physical health at baseline and this difference was more pronounced at last follow-up. ‘Mental health' (the second QoL dimension of the SF-36) improved significantly from 19.4 (SD 4.5) at baseline to 29.99 (SD 11.2) at last follow-up for the sample as a whole. Thus, the group as a whole moved about 1 SD from ‘much below average' (–3 SD) to ‘below average' (–2 SD). Descriptively, responders improved more than non-responders.

In addition to observed long-term changes, acute effects occurred frequently after parameter change. Patients had acute improvements of depression, anxiety, and anhedonia lasting up to 2 weeks. These acute effects were not predictive for long-term outcome. Only weak symptoms of hypomania (elevated mood, less hours of sleep) were observed in two patients after parameter change, which disappeared within 24 h and did not meet diagnostic criteria for hypomania.

Comprehensive neuropsychological assessment revealed no detrimental effects on cognitive function after 12 months in a paper by Grubert et al (2011) on 10 patients of our current sample. In the contrary, cognitive performance significantly improved in tests of attention, learning and memory, executive functions, and visual perception during first year of follow-up. In addition, there was a general trend toward cognitive improvement from below average to average performance (Grubert et al, 2011). These effects were independent of the antidepressant effects of NAcc-DBS or changes in NAcc-DBS parameters (see for details). Analysis of the assessment at last observation (24 to 36 months) confirmed no changes in cognition from baseline except for nonverbal fluency, which was significantly improved at last follow-up (see Table 3 for an overview on tests and statistical analysis).

Table 3. Neuropsychological Assessment of Cognitive Changes at Baseline and at Last Observation.

| Cognitive domain/test | Mean | N | SD |

Paired samples t-test

|

T-value | df | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change | SD change | |||||||

| Verbal learning and memory | ||||||||

| VLMT total learning | ||||||||

| Baseline | 40.3 | 10 | 12.28 | −1.20 | 15.67 | −0.24 | 9.00 | 0.81 |

| Last observation | 41.50 | 10 | 14.88 | |||||

| VLMT delayed recall | ||||||||

| Baseline | 7.40 | 10 | 2.76 | −0.40 | 4.17 | −0.30 | 9.00 | 0.77 |

| Last observation | 7.80 | 10 | 3.43 | |||||

| VLMT recognition | ||||||||

| Baseline | 12.10 | 10 | 2.13 | −0.50 | 1.96 | −0.81 | 9.00 | 0.44 |

| Last observation | 12.60 | 10 | 2.17 | |||||

| General cognitive functions | ||||||||

| MMSE | ||||||||

| Baseline | 28.73 | 11 | 1.68 | 0.09 | 2.02 | 0.15 | 10.00 | 0.88 |

| Last observation | 28.64 | 11 | 1.43 | |||||

| Language | ||||||||

| HAWIE lexis test | ||||||||

| Baseline | 18.78 | 9 | 4.32 | −0.11 | 3.10 | −0.11 | 8.00 | 0.92 |

| Last observation | 18.89 | 9 | 3.55 | |||||

| HAWIE finding similarities | ||||||||

| Baseline | 22.67 | 9 | 5.00 | −1.22 | 3.19 | −1.15 | 8.00 | 0.28 |

| Last observation | 23.89 | 9 | 4.04 | |||||

| Working memory | ||||||||

| Wechsler digit span | ||||||||

| Baseline | 13.09 | 11 | 2.95 | −0.18 | 2.79 | −0.22 | 10.00 | 0.83 |

| Last observation | 13.27 | 11 | 4.76 | |||||

| Wechsler visual memory span | ||||||||

| Baseline | 13.45 | 11 | 3.50 | 1.18 | 3.25 | 1.21 | 10.00 | 0.26 |

| Last observation | 12.27 | 11 | 5.62 | |||||

| Executive function | ||||||||

| TMT A (s) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 52.73 | 11 | 29.12 | −3.91 | 14.23 | −0.91 | 10.00 | 0.38 |

| Last observation | 56.64 | 11 | 32.87 | |||||

| TMT B (s) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 134.64 | 11 | 87.49 | −30.82 | 49.90 | −2.05 | 10.00 | 0.07 |

| Last observation | 165.45 | 11 | 113.31 | |||||

| STROOP interference (s) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 302.57 | 7 | 70.23 | −7.43 | 29.07 | −0.68 | 6.00 | 0.52 |

| Last observation | 310.00 | 7 | 76.16 | |||||

| Five-point test | ||||||||

| Baseline | 20.20 | 10 | 10.84 | −5.80 | 5.45 | −3.36 | 9.00 | 0.01 |

| Last observation | 26.00 | 10 | 10.75 | |||||

| Visual spatial learning and memory | ||||||||

| RVDLT total learning | ||||||||

| Baseline | 27.20 | 10 | 9.05 | −5.50 | 10.50 | −1.66 | 9.00 | 0.13 |

| Last observation | 32.70 | 10 | 14.62 | |||||

| RVDLT delayed recall | ||||||||

| Baseline | 6.10 | 10 | 2.92 | −0.50 | 2.22 | −0.71 | 9.00 | 0.50 |

| Last observation | 6.60 | 10 | 3.34 | |||||

| RVDLT recognition | ||||||||

| Baseline | 24.89 | 9 | 2.03 | 1.00 | 2.92 | 1.03 | 8.00 | 0.33 |

| Last observation | 23.89 | 9 | 4.01 | |||||

| Visual perception | ||||||||

| VOT | ||||||||

| Baseline | 18.00 | 8 | 4.99 | −1.75 | 2.62 | −1.89 | 7.00 | 0.10 |

| Last observation | 19.75 | 8 | 5.00 | |||||

| Attention | ||||||||

| D2 total minus errors | ||||||||

| Baseline | 280.44 | 9 | 124.47 | −5.44 | 51.57 | −0.32 | 8.00 | 0.76 |

| Last observation | 285.89 | 9 | 97.84 | |||||

Abbreviations: HAWIE, Hamburg Wechsler Intelligence Test for adults; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; RVDLT, Rey Visual Design Learning Test; TMT, Trail Making Test; VLMT, Verbal Learning and Memory Test; VOT, Hooper Visual Organization Test.

Mean, number of patients in analysis, SD, two-tailed paired t-tests with scores at baseline and at last observation (24 to 36 months) within each test as dependent variable. Percentile rank (PR) at baseline and last follow-up comparing our data with published normative data.

Stimulation Parameters

Stimulation parameters varied between patients. Most patients were stimulated between 5 and 8 V, at 90 μs, 130 Hz, monopolar. Individual best settings were analyzed and parameters only changed (mostly raise in amplitude or change of contacts) when side effects occurred or when the antidepressant response was not satisfying. In three patients, wider pulse widths or higher frequencies led to an increase in tension and restlessness. Small differences could be found on average between responders and non-responders: non-responders experienced parameter changes more frequently and later during follow-up (responders had only minor parameter adjustment after 13 months, whereas non-responders had parameter changes on average at 17 months). Responders were stimulated little less than non-responders (responders: 6.8 V/90 PW/130 rate, non-responders: 7.1 V/100 PW/135.5 rate on average). After approximately 6 months, most patients had all four contacts activated negative against the case.

Adverse Events and Dropouts

Adverse events were either related to the surgical procedure (eg, swollen eye, dysphagia, pain), directly to parameter change (eg, erythema, subjective transient increase in anxiety or tension, sweating, within minutes to few hours) (see Table 4) or unrelated to the DBS treatment (eg, gastritis, leg fracture, herniated disc). Most importantly, all side effects related to the DBS treatment were transient or could be stopped immediately by means of parameter change, so that patients did not suffer any permanent adverse effects.

Table 4. Adverse Events.

| Adverse events | Related to surgical procedure | Related to parameter change | Unrelated to DBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure | 1 | ||

| lead dislodgment | 1 | ||

| Dysphagia | 3 | ||

| Pain | 4 | ||

| Swollen eye | 6 | ||

| Psychotic symptoms | 1 | ||

| Muscle cramps | 1 | ||

| Vision/eye movement disorder | 1 | ||

| Headache | 1 | ||

| Paresthesia | 2 | ||

| Transient mood elevation | 2 | ||

| Agitation | 3 | ||

| Disequilibrium | 3 | ||

| Erythema | 4 | ||

| Transient increase in anxiety (subjective) | 4 | ||

| Increased sweating | 4 | ||

| Suicide attempt | 1 | ||

| Suicide | 1 | ||

| Dyskinesia | 1 | ||

| Syncope | 1 | ||

| Herniated disc | 1 | ||

| Aneurysm in groin | 1 | ||

| Reduced pulmonary function | 1 | ||

| Cataract surgery | 1 | ||

| Breast cancer | 1 | ||

| Leg fracture | 2 | ||

| Aconuresis | 2 | ||

| Gastritis | 5 |

Number of patients experiencing adverse events related to the surgical procedure, to parameter changer or judged to be unrelated to DBS.

One patient attempted suicide and one patient committed suicide during 12 months follow-up. These patients were non-responders to DBS.

One patient had the device explanted after 2 years because of breast cancer and associated infection after chemotherapy. Two patients have been followed under 24 months; five patients have been tracked for 4 years. In order to prevent overestimation of clinical effect, all patients (n=11) contributed in an intent-to-treat analysis to all points in time.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated sustained antidepressant effects over 2 years of NAcc-DBS in 11 patients suffering from severe TRD. Some patients were followed up to 4 years (last observation).

Effect of NAcc-DBS on TRD

Response rates

About 45% of patients responded significantly (reduction in HDRS ⩾50% in all studies) during the first 6 months of NAcc-DBS and reached the response threshold after 12 months of stimulation at the latest (for a detailed description of response during first year of follow-up see Bewernick et al (2010)). This response rate was similar to studies on other stimulation targets after 24 months, namely Cg25 (Kennedy et al, 2011; Lozano et al, 2008) and ventral striatum (Malone, 2010; Malone et al, 2009) (Cg25: response rate 45% after 24 months, 55% at last follow-up; ventral striatum: response rate 53.3%) and 12 months (ventral striatum: response rate 53 after 12 months, 71% at last follow-up, ranging from 14 to 67 months).

Comparing time courses of response in DBS studies with courses in TAU studies using pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or ECT, DBS-induced changes seem to require more time than effects induced by conventional treatment methods; first antidepressant effects could be observed after first months, however, the establishment of stable amelioration required up to 6 months, which might be at least partly explained by the need to adapt stimulation parameters for treatment optimization.

Typical 24 months response rates in TAU studies for TRD (mostly pharmacotherapy) are around 19% (Dunner et al, 2006). Response rates of DBS in the present small sample as well as in other studies on Cg25 (Kennedy et al, 2011) and ALIC seem to be substantially higher, keeping in mind that the selected patients were per inclusion criteria non-responders to conventional treatments.

Stability of antidepressant effect

After about 8–12 months of treatment, patient's response status never changed, thus response remained stable during second year and up to 4 years. Responders had a sustained reduction in depressive and anxiety. Clinically equally important, the significant anti-anhedonic effect measured as number of positive activities remained also stable in responders during follow-up. This stabilization in psychopathological measures was also reflected in social functioning. QoL (mental health) changed from ‘far below average' to ‘slightly below average', whereas the patient's physical health score did not change. It has to be kept in mind that the main burden on the patient is depression itself causing reduced QoL. Nonetheless, patients started to work part-time, took care of their personal matters, resumed new hobbies, one patient developed the desire to have a child, and so on. In this small group of patients, these anecdotal changes were more convincing than any QoL measure could possibly point out.

It has to be kept in mind that no conventional treatment method (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and ECT) lead to significant amelioration of any of these patients before and the majority of patients had not been in remission since first diagnosis. This long-term antidepressant effect is especially remarkable as in conventional antidepressant treatment approaches relapse is the rule. Relapse rates are up to 90% for third episode patients (Rush et al, 2006). The more treatment steps a patient requires, the higher will be the relapse rate (Rush et al, 2006). In the present sample, all patients had by definition numerous treatment steps and several or decades lasting episodes. After conventional treatments, most patients relapse within the first 6 months (Kellner et al, 2006; Rush et al, 2006). Studies on treatment as usual, assessing long-term effect beyond 1 year are rare in depression research. In this study, none of the responders suffered an aggravation in depression in 2 to 4 years.

Thus, DBS seems to be a promising therapy option for TRD so far, offering persistent antidepressant effects over many years.

Non-responders

More parameter settings were tried in the group of non-responders compared with the responders. Unfortunately, only short time or minimal long-term (from 5 to 45% response) antidepressant effects could be achieved in these patients. Increasing experience with NAcc-DBS allow more effective parameter search procedures and larger patient samples will make it possible to evaluate predictors of response. Although, antidepressant effects were small in the group of non-responders, only one patient even considered removing the DBS system but chose to remain stimulated. It is debatable, if non-responders to one target might be implanted to another target currently under research (eg, Cg25, medial forebrain bundle, and habenula). Non-responders did not differ from responders in depression score at baseline or in demographic characteristics, but more men were classified as non-responders compared with women.

Cognition

It has been demonstrated at two target sites that DBS does not have negative effects on cognition (Grubert et al, 2011; McNeely et al, 2008). To the contrary, we demonstrated cognitive improvements in 10 patients treated with NAcc-DBS, which were not explained by the improvement in depression severity and could be shown independent of response status (Grubert et al, 2011). Analysis of last observation (24 to 36 months) compared with baseline performance have demonstrated no negative and in the domain of nonverbal fluency even an amelioration of function. Larger samples will further investigate possible procognitive effects in several cognitive domains.

Side effects and adverse events

Side effects occurred rarely directly after parameter change (minutes to few hours) and could be counteracted by small adjustments of stimulation settings. Adverse events were related to the surgery or not related to DBS as assessed by the investigator. One patient committed suicide and one patient attempted suicide during first year. It has to be taken into account that severe depression is associated with a 4–5 times elevated risk for suicide compared with moderate or mild depression (Hardy, 2009). Given the high risk of suicide (approximately 15% in TRD) (Isometsa et al, 1994; Wulsin et al, 1999) and compared with the suicide rate found in DBS to Cg25 (10%) (Kennedy et al, 2011), in our sample, the one tragic suicide of a patient (suicide rate in our sample 9%) still remains below statistical expectation. Therefore, and because the suicide was judged not to be related to the simulation (Bewernick et al, 2010), DBS as treatment option for TRD should not be abandoned because of risk of suicide, but close patient tracking is necessary as well as close collaboration with additional health care providers (local psychiatrist, psychotherapy, and professional social support).

Given robust antidepressant effects and minimal side effects, patients were very compliant to DBS-related duties (battery recharge, regular visits).

Parameters

It was important to carefully determine individual best parameters. This required frequent visits during first months. Acute effects at the beginning of treatment were not predictable for long-term outcome. Stable clinical effects after parameter change occurred within 2 to 4 weeks, thus it is generally not indicated to change parameters more frequently. Depending on stimulation parameters, patients daily recharge the battery for up to 2 h (n=5 patients) or need to have a battery replacement about once every 15 months (n=6).

Limitations

All DBS studies so for are reporting on a relatively small number of patients, thus response ratios between 40 and 60% (Kennedy et al, 2011; Lozano et al, 2008; Malone et al, 2009; Mayberg et al, 2005) are limited in interpretation. Especially in long-term studies, dropouts, and patients who have not yet completed the whole observation period require special care in statistical analysis. Obviously, larger sample sizes are needed to convincingly ascertain clinical efficacy.

At study initiation, first patients entered a blinded sham stimulation phase. Owing to symptom aggravation and delayed recurrence as well as weaker antidepressant effect, the design was changed leaving out the sham condition. These problems have been reported also by Holtzheimer et al (2012) during a single-blind discontinuation phase in therapy-resistant depression and by Denys et al (2010) in patients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder. This is a strong limitation in respect to placebo effects. Although this study was not sham controlled, none of our patients was able to guess immediately whether the stimulator is on or off. Incidental interruption of stimulation (for reason of battery depletion or programming error), always led to an aggravation of symptoms after several days to weeks (for a discussion of placebo-effects in TRD, see Bewernick et al, 2010). In further studies it has to be planned thoroughly how a sham condition can be included in the design, possibly as a lead-in sham condition. A discontinuation criterion (eg, suicidal ideation, increase in depression score to 70% of baseline score) has to be determined prior.

Stimulation amplitudes were higher than in DBS for the treatment of neurological diseases. This applies to all targets under research so far (Cg25, ALIC, and NAcc). This requires regular battery recharge (2 h per day) or battery exchange (every 8–15 months) and means an additional burden for the patient. As all targets are interconnected in the neuronal network for mood regulation (Krishnan and Nestler, 2010; Nestler and Carlezon, 2006), it is questionable, if the optimal target has been found. Actually, the medial forebrain bundle is under debate as a new target possibly reducing electric current (Coenen et al, 2011).

Conclusion/outlook

DBS to the NAcc has demonstrated sustained antidepressant effects over up to 4 years in a small sample. Anxiolytic effects and amelioration of social functioning were observed at this stimulation site. A favorable side-effect profile contributed to very good compliance and adherence. Nonetheless, surgical risk and the possible aggravation of depression or other psychiatric side-effects (especially suicidality) require a very experienced team of experts; neurosurgeons specialized in stereotactic surgery, psychiatrist experts in the treatment of depression, psychologist to assess severity of depression and cognitive effects. In addition, a central registry for DBS should guarantee that positive and negative results as well as information from small feasibility and single case studies are brought to notice to the scientific community (Synofzik et al, 2011). Taken into account small sample size in all DBS studies in depression, larger studies have to be initiated before DBS can be seen as treatment option in less severe TRD.

Acknowledgments

We thank patients and their relatives for participating in this study.

This investigator-initiated study was supported in part (DBS device, battery exchange and limited support for study nurse) by a grant of Medtronic to Drs Schlaepfer and Dr Sturm are members of a project group, ‘Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatry: Guidance for Responsible Research and Application,' funded by the Volkswagen Foundation (Hanover, Germany). The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsor had no influence on design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kayser S, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz B, et al. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cersosimo MG, Raina GB, Benarroch EE, Piedimonte F, Alemán GG, Micheli FE. Micro lesion effect of the globus pallidus internus and outcome with deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease and dystonia. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1488–1493. doi: 10.1002/mds.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen VA, Schlaepfer TE, Maedler B, Panksepp J. Cross-species affective functions of the medial forebrain bundle-implications for the treatment of affective pain and depression in humans. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1971–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denys D, Mantione M, Figee M, van den Munckhof P, Koerselman F, Westenberg H, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1061–1068. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunner D, Rush A, Russell J, Burke M, Woodard S, Wingard P, et al. Prospective, long-term, multicenter study of the naturalistic outcomes of patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:688–695. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Cohen J, Nee J, Fleiss J, Sarantakos S. Hamilton depression rating scale. Extracted from regular and change versions of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:98–103. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780260100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granziera C, Pollo C, Russmann H, Staedler C, Ghika J, Villemure JG, et al. Sub-acute delayed failure of subthalamic DBS in Parkinson's disease: the role of micro-lesion effect. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubert C, Hurlemann R, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Hadrysiewicz B, Axmacher N, et al. Neuropsychological safety of nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for major depression: effects of 12-month stimulation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:516–527. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.583940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M.1976HAMA Hamilton Anxiety Scale National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy P. [Severe depression : morbidity-mortality and suicide] Encephale. 2009;35 (Suppl 7:S269–S271. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(09)73484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger M. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Depressionen. Beltz: München Weinheim; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzheimer PE, Kelley ME, Gross RE, Filkowski MM, Garlow SJ, Barrocas A, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:150–158. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff W, Lenartz D, Schormann M, Lee SH, Kuhn J, Koulousakis A, et al. Unilateral deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: outcomes after one year. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Heikkinen ME, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lönnqvist JK. Suicide in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:530–536. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner CH, Knapp RG, Petrides G, Rummans TA, Husain MM, Rasmussen K, et al. Continuation electroconvulsive therapy vs pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in major depression: a multisite study from the Consortium for Research in Electroconvulsive Therapy (CORE) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SH, Giacobbe P, Rizvi SJ, Placenza FM, Nishikawa Y, Mayberg HS, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: follow-up after 3 to 6 years. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:502–510. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10081187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. Linking molecules to mood: new insight into the biology of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1305–1320. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.10030434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Graf M. Pleasant activities and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;41:261–268. doi: 10.1037/h0035142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano AM, Mayberg HS, Giacobbe P, Hamani C, Craddock RC, Kennedy SH. Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DA., Jr Use of deep brain stimulation in treatment-resistant depression. Cleveland Clinic J Med. 2010;77 (Supplement 3:S77–S80. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77.s3.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DA, Jr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Friehs GM, Eskandar EN, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely HE, Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Kennedy SH. Neuropsychological impact of Cg25 deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: preliminary results over 12 months. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:405–410. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181710927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A.1996The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 Projected to 2020 Harward University Press; Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun MS, Rodriguez RL, Mikos A, Miller K, Kellison I, Kirsch-Darrow L, et al. Deep brain stimulation and the role of the neuropsychologist. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21:162–189. doi: 10.1080/13825580601025940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus HA, Pettit AR. The societal costs of chronic major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl 6:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal SH, Klerman GL. Endogenous features of depression in women. Can Psychiatric Assoc J. 1966;11 (Suppl:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl 16:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer T, Lieb K. Deep brain stimulation for treatment refractory depression. Lancet. 2005;366:1420–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, Kosel M, Brodesser D, Axmacher N, et al. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropschopharmacology. 2008;33:368–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreen OS. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. Oxford University Press: New York; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M, Fins J, Schlaepfer TE.2011A neuromodulation experience registry for deep brain stimulation studies in psychiatric research: rationale and recommendations for implementation Brain Stimulatione-pub ahead of print; dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin LR, Vaillant GE, Wells VE. A systematic review of the mortality of depression. Psychosomatic Med. 1999;61:6–17. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]